GARFIELD: THE MOVIE

DIRECTED BY: Peter Hewitt

WRITTEN BY: Joel Cohen and Alec Sokolow

RELEASE DATE: June 11, 2004

FILM RATING: **

MURRAY RATING: **

PLOT: A morbidly obese cat must cope with the arrival of his owner’s new puppy.

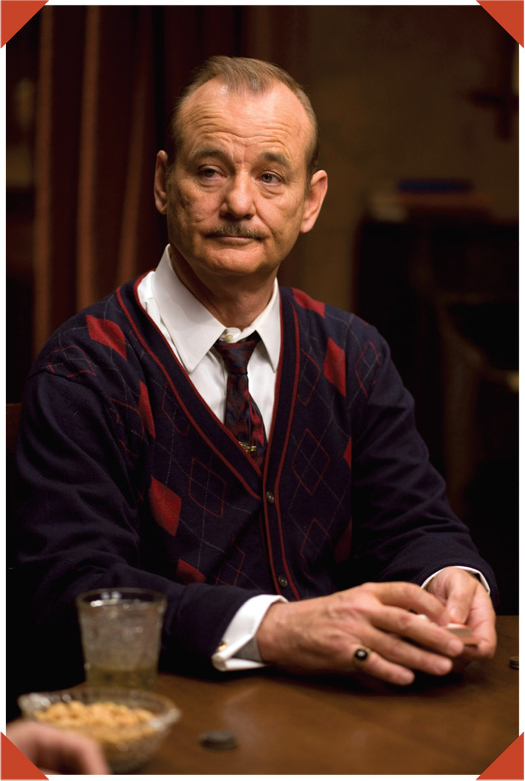

STARRING BILL MURRAY AS: Garfield the Cat

Murray gives vocal life to the lasagna-loving feline in this enervating big-screen adaptation of Jim Davis’s popular comic strip. (Oddly enough, the television voice of Garfield, Lorenzo Music, was also the voice of Peter Venkman in the Ghostbusters cartoon series.) Though savaged by critics and derided by most of Murray’s fans, Garfield: The Movie was an enormous box office hit and spawned the superior 2006 sequel, Garfield: A Tail of Two Kitties. “I wasn’t thinking clearly,” Murray said of his participation in the Garfield enterprise. He once called Garfield: The Movie “more than I’d bargained for” and “sort of like Fantastic Mr. Fox without the joy or the fun.”

In interviews conducted after Garfield: The Movie’s release, Murray admitted he accepted the role only because he was under the mistaken impression that Academy Award–winning screenwriter Joel Coen had written the script. The screenplay for Garfield was in fact written by Joel Cohen, a journeyman best known for his work on the family comedies Cheaper by the Dozen and Daddy Day Camp. “I thought it would be kind of fun, because doing a voice is challenging, and I’d never done that,” Murray told New York magazine’s Vulture blog (apparently forgetting about his work in Shame of the Jungle and B.C. Rock). “Plus, I looked at the script, and it said, ‘So-and-so and Joel Coen.’ And I thought: ‘Christ, well, I love those Coens! They’re funny.’ So I sorta read a few pages of it and thought, ‘Yeah, I’d like to do that.’”

After some haggling, the price was right as well. “I had these agents at the time, and I said, ‘What do they give you to do one of these things?’ And they said, ‘Oh, they give you $50,000.’ So I said, ‘Okay, well, I don’t even leave the fuckin’ driveway for that kind of money.’ Then this studio guy calls me up out of nowhere, and I had a nice conversation with him. No bullshit, no schmooze, none of that stuff. We just talked for a long time about the movie. And my agents called on Monday and said, ‘Well, they came back with another offer, and it was nowhere near $50,000.’ And I said, ‘That’s more befitting of the work I expect to do!’”

“GARFIELD, MAYBE.”

Murray’s enthusiasm for the project waned once he got in the recording studio. He spent several eight-hour days in a cramped booth guzzling coffee and perspiring through his shirt, desperately trying to ad-lib his way out of the hackneyed fat jokes that had been written for him. “I worked all day and kept going, ‘That’s the line? Well, I can’t say that.’ And you sit there and go, ‘What can I say that will make this funny? And make it make sense?’ And I worked. I was exhausted, soaked with sweat, and the lines got worse and worse. And I said, ‘Okay, you better show me the whole rest of the movie, so we can see what we’re dealing with.’ So I sat down and watched the whole thing, and I kept saying, ‘Who the hell cut this thing? Who did this? What the fuck was Coen thinking?’ And then they explained it to me: It wasn’t written by that Joel Coen.”

Retakes were ordered and continued in Italy, where Murray was on location shooting his next film, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou. He later credited his improvisations with salvaging the film: “We managed to fix it, sort of. It was a big financial success. And I said, ‘Just promise me you’ll never do that again.’” The promises must have been persuasive, because Murray signed on for the follow-up two years later.

NEXT MOVIE: This Old Cub (2004)

GARFIELD: A TAIL OF TWO KITTIES

DIRECTED BY: Tim Hill

WRITTEN BY: Joel Cohen and Alec Sokolow

RELEASE DATE: June 16, 2006

FILM RATING: ***

MURRAY RATING: ***

PLOT: The tubby tabby trades places with an English royal.

STARRING BILL MURRAY AS: Garfield, again

To the astonishment of the nation’s critics (except Roger Ebert, who gave Garfield: The Movie three stars out of four), Murray returned for a second helping of lasagna in this inevitable sequel to the 2004 smash. If anything, he had an even worse experience. In interviews, he has all but disowned A Tail of Two Kitties, labeling it a “miscarriage” that was “beyond rescue” and “even more trouble” than the original. Having already played the “I thought it was a Coen Brothers movie” card, Murray pinned the blame for Tail’s creative deficiencies on meddling by the suits. “The first one had so much success,” he said. “Success has many fathers—so by the time the second one rolled around there were, like, nine people having lots of input, including the studio head.” Director Tim Hill was also singled out for Murray’s ire. “There were too many crazy people involved with it,” the actor told a group of Reddit “Ask Me Anything” inquisitors in 2014. “I thought I fixed the movie, but the insane director who had formerly done some SpongeBob, he would leave me and say ‘I gotta go, I have a meeting’ and he was going to the studio where someone was telling him what it should be, countermanding what I was doing.”

Perhaps the voice of Garfield doth protest too much. While it will never be mistaken for Fantasia, Garfield: A Tail of Two Kitties is a vast improvement over its predecessor and represents Murray’s finest vocal work to date. The plot, lifted from Mark Twain’s novel The Prince and the Pauper, relies less on the hackneyed dog-versus-cat humor that bogged down the first movie. Delightful verbal and visual jokes abound. Though his public utterances belie it, Murray seems to be having more fun despite having to share screen time with Tim Curry as the voice of Garfield’s English “cousin.” Best of all, the characters of Garfield’s owner and his girlfriend (played by the insipid Breckin Meyer and Jennifer Love-Hewitt) are deemphasized in favor of a brilliant supporting cast headlined by Billy Connolly as the scheming Lord Dargis. If this was a “miscarriage,” fewer animated movies should go to term.

NEXT MOVIE: The Darjeeling Limited (2007)

September 21, 1970, was Bill Murray’s twentieth birthday. It was also one of the worst days of his life. After a family birthday celebration in Chicago, Murray was all set to fly back to Denver to resume his pre-med studies at Regis College. As he was waiting in line to board his flight at O’Hare International Airport, he made the mistake of telling one of his fellow passengers that he was carrying two bombs in his suitcase. A ticket agent overheard Murray’s joke and immediately summoned a couple of U.S. marshals, who proceeded to root through Murray’s luggage. They didn’t find any explosives, but they did discover five two-pound “bricks” of marijuana. That much weed was worth $20,000 at the time (about six times as much today). In a panic, Murray tried to stash the pot-filled bags in a locker, but Chicago vice cops arrived on the scene and arrested him. He did manage to swallow a check from one of his “customers” before cops confiscated his suitcase. “That guy owes me his life and reputation,” Murray said later.

Murray was charged with possession of marijuana and ordered to appear in narcotics court the next day. The bust made the front page of the Chicago Tribune. Because he was a first-time offender, Murray was spared jail time and placed on probation for five years. But his college career was over. After talking it over with his family, Murray opted to drop out of Regis before his criminal record got him kicked out.

GAROFALO, JANEANE

The stand-up comic, actress, and ’90s icon considers Murray her personal hero. In 1982, she wrote an entire essay about her admiration for him as part of her application packet to Providence College. The two first met on November 12, 1994, during Garofalo’s lone unhappy season on Saturday Night Live. Murray had dropped by to deliver a eulogy for the recently deceased SNL writer Michael O’Donoghue. “I saw him by the craft service table,” Garofalo told the UCLA Daily Bruin. “I was dressed as Dorothy for a horrendously bad Wizard of Oz sketch, and I went and pretended that I had something to do by the coffee machine… . I went up and stood extra near him and then conjured up some question to ask someone near him and said, ‘Hello,’ and shook his hand.” Four months later, in March 1995, Garofalo quit SNL midseason. “I think he was impressed when I quit,” Garofalo said. “He was impressed with the balls it took to quit the show.” In fact, Murray was so impressed that he lobbied hard for Garofalo to be cast opposite him as a kindly zookeeper in his 1996 film Larger Than Life.

GET LOW

DIRECTED BY: Aaron Schneider

WRITTEN BY: Chris Provenzano, C. Gaby Mitchell, and Scott Seeke

RELEASE DATE: July 30, 2010

FILM RATING: ***

MURRAY RATING: **

PLOT: A cantankerous old hermit plans his funeral.

STARRING BILL MURRAY AS: Frank Quinn, Depression-era funeral director

Refining a character he created for the classic 1998 Saturday Night Live sketch “Who’s More Grizzled?” Robert Duvall plays a backwoods curmudgeon harboring a dark secret in this Faulknerian period piece loosely based on a true story. Murray provides able support as the undertaker who helps Duvall’s character choreograph his own elaborate funeral service. A showcase for the performances of its two stars, Get Low was somewhat surprisingly snubbed by all the major award-granting entities.

Murray came to the project via the usual circuitous route: entreaties to his attorney, scripts sent to mysterious post office boxes, weeks of radio silence followed by an out-of-the-blue phone call expressing his interest in joining the production. In the end, it took a personal plea from director Aaron Schneider to seal the deal. “I sat down and I wrote a letter,” Schneider told an interviewer. “Took me like two or three days to write it because it’s like, how do you write a letter to Bill Murray? Dear Bill, then what? I finally just decided to tell him, kind of put my heart on the page and said here’s why we want you and here’s what I think this could be.” Whatever Schneider wrote, it must have impressed Murray, who was recovering from the heartbreak of his second divorce at the time and thought he might never work again. He immediately said yes, though his superstitious insistence on not signing a contract nearly jeopardized the film’s tenuous financing.

The opportunity to work with one of his acting idols may have also factored into Murray’s decision to accept the part. “I’ve always liked [Duvall’s] stuff,” he told Entertainment Weekly. “I think he’s incredibly real and a certain kind of actor that all actors go, ‘Okay, I give. That guy, he’s better than I am.’ You can’t really pass up that opportunity to work with someone who has more stuff than you, because it’s part of your education. It was amazing to see how accessible all his emotions are and how he was able to touch all these things in an instant. You realize you have a long ways to go.” The chance to observe Duvall in his natural thespian habitat, playing a crusty old hermit who might as well be Boo Radley’s grandfather, was too good to pass up. Or, as Murray put it in another interview: “[Duvall] can coot with the best of them.”

For his own part, which Murray somewhat unfairly described as “a bozo on the side,” the actor drew on the experience of his grandfather, who once worked as a greeter in a funeral home. “He was such an amazing person,” Murray told the New York Post. “He would just be there as if he were a friend to the deceased, and people would talk to him about the deceased. When he died himself, there was an enormous turnout for him, because all these people had become friends with him at their own family’s funerals.” On the challenge of holding his own on-screen alongside Duvall, he said: “You’re playing behind the beat, because he’s set in this crazy rhythm, and you’re sort of chasing a meat wagon that’s rolling down the street. It’s either challenging or nervous, but you know that he can do anything you can do, so you don’t wanna aim low. You don’t wanna throw a softball out there. You gotta just open a can of beans on him every time, because that’s your job. I’m gonna push him as hard as I can to get the best out of him. It’s like testing spaghetti. You throw it on the wall and see what happens.”

Financial backing for Get Low came, in part, from investors in Poland. That compelled Murray and the rest of the cast and crew to spend Thanksgiving 2009 promoting the film at the International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography in Lodz, Poland. Murray described the junket as “a total blast … much cooler than Cannes.” Asked to present an award at the festival, Murray regaled the crowd by opening with “I love you, may I borrow some money?” in fluent Polish. He and producer Dean Zanuck followed that up with a road trip to Warsaw, where they crashed a stranger’s house party and sat in the front row at a Polish fashion show. “With Bill, you never know where you are going to end up,” Zanuck later confided. “You come to expect the unexpected.”

NEXT MOVIE: Passion Play (2010)

GET SMART

DIRECTED BY: Peter Segal

WRITTEN BY: Tom J. Astle and Matt Ember

RELEASE DATE: June 20, 2008

FILM RATING: *½

MURRAY RATING: *

PLOT: After being passed over for a promotion, an aspiring spy infiltrates a terrorist organization to prove his mettle.

STARRING BILL MURRAY AS: Agent 13

Murray has a brief cameo in this ghastly unnecessary reboot of the classic TV sitcom about an inept secret agent. In a scene that seems to have no relation to the rest of the film, he plays Agent 13, an operative for CONTROL who inexplicably plies his trade from inside a hollowed-out tree on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

NEXT MOVIE: City of Ember (2008)

GHOSTBUSTERS

DIRECTED BY: Ivan Reitman

WRITTEN BY: Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis

RELEASE DATE: June 7, 1984

FILM RATING: ***

MURRAY RATING: ****

PLOT: A trio of paranormal investigators (plus Ernie Hudson) thwarts a ghost invasion of New York City.

STARRING BILL MURRAY AS: Peter Venkman, leader of the Ghostbusters

In the summer of 1984, three goliaths bestrode the American cultural landscape: Bruce Springsteen, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Murray—star of the season’s highest-grossing film, Ghostbusters. Saturday Night Live may have made Murray a household name, but this crowd-pleasing, special-effects-driven supernatural action comedy put his smirking puss on every school lunchbox from coast to coast. Depending on your taste—and the age you were when you first saw it—Ghostbusters may not be the best film of Bill Murray’s career, but it’s unquestionably the most important.

An evolutionary leap forward in the chain of comedy blockbusters that began with The Blues Brothers, Ghostbusters likewise sprang from the fertile mind of one man: Dan Aykroyd. Murray’s former SNL cast mate and a lifelong believer in the supernatural (several of his relatives were professed spiritual mediums), Aykroyd modeled his script on the ghost-hunting comedies of Bob Hope and Abbott and Costello. He wrote it for himself and John Belushi, but Belushi’s tragic death in March 1982 compelled him to rethink the entire project. Aykroyd showed his screenplay-in-progress to director Ivan Reitman, who suggested a repeat of the successful Stripes formula: entice Harold Ramis to join the cast and then have him do a rewrite tailored to the strengths of Murray in the Belushi role. Thus Dr. Peter Venkman, libidinous parapsychologist and nominal leader of the Ghostbusters team, was born. Aykroyd and Ramis rounded out the trio as Raymond Stantz and Egon Spengler, “the Lion and the Tin Man” to Murray’s Scarecrow. Or as Murray put it: “They figured out that I would be the mouth, Dan would be the heart, and Harold would be the brains.”

When Aykroyd sent him the finished screenplay, Murray was impressed. In fact, he saw no need to improve it with his trademark improvisations. “I’d never worked on a movie where the script was good,” he said later. “Stripes and Meatballs, we rewrote the script every single day.” There was just one hang-up. Murray was gung-ho to get his passion project, The Razor’s Edge, green-lit by a major studio. Dan Aykroyd counseled him to say yes to Ghostbusters on the condition that Columbia Pictures bankroll The Razor’s Edge as well. “Forty-five minutes later, we had a caterer and a producer and a director for The Razor’s Edge,” Murray said.

Filming of Ghostbusters was scheduled to begin in the fall of 1983, immediately after Murray finished work on the exhausting Razor’s Edge shoot in India. With Aykroyd and Ramis all set to go before the camera, studio executives went into a full-blown panic over Murray’s whereabouts. They bombarded him with international telegrams demanding that he show up on the Ghostbusters set in New York in time for the first day of shooting. At one point, Murray made the mistake of calling in from a phone booth at the Taj Mahal, only to be ordered home by a Columbia suit with little regard for the difficulties involved in adapting Somerset Maugham’s classic novel.

After a brief stopover in London, Murray finally made it home on the Concorde. Ramis and Reitman personally met him at John F. Kennedy International Airport for an impromptu “story conference.” Murray “came through the terminal with a stadium horn—one of those bullhorns that plays eighty different fight songs,” Ramis later recalled. “He was addressing everyone in sight with this thing and then playing a song. We dragged him out of there and went to a restaurant in Queens. I’ve never seen him in higher spirits. We spent an hour together, and he said maybe two words about the whole script. Then he took off again.”

The boisterous behavior continued on the location set in midtown Manhattan. On the first day of shooting, Reitman squired the dazed and jet-lagged Murray over to the wardrobe department. (“I still had no idea if he’d actually read the script,” the director said later.) After trying on his costume, Murray realized he’d lost a significant amount of weight in India. “So I started eating right away. A production assistant said, ‘Do you want a cup of coffee?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, and I want a couple of doughnuts, too.’” On being introduced to costar Sigourney Weaver for the first time, outside the New York Public Library, Murray greeted her with a hearty “Hello, Susan.” Then he picked her up, threw her over his shoulder, and carried her down the street. “It was a great metaphor for what happened to me in the movie,” Weaver said later. “I was just turned upside down and I think I became a much better actress for it.”

Once the initial adrenaline rush wore off, Murray found the first month of the Ghostbusters shoot an enervating slog. “For the first few weeks, I was getting beaten to go to work,” he said. “It was like, ‘Where’s Bill?’ ‘Oh, he’s asleep.’ Then they’d send three sets of people to knock on the door and say, ‘They really want you.’ I’d stumble out and do something and then go back to sleep. I kept thinking to myself: ‘Ten days ago I was up there working with the high lamas in a gompa, and here I am removing ghosts from drugstores and painting slime on my body.’” As autumn wore on, however, he caught his second wind. The cast’s spirits were buoyed by the tremendous response they received from ordinary New Yorkers, who quickly learned to identify the ’Busters by their distinctive beige jumpsuits. “It was tremendous fun running around New York City in those suits,” Harold Ramis said. “People would cheer; restaurants would stay open after hours for us. And even if they couldn’t see who we were, they were seeing this ambulance with the logo on it.”

That “no ghost” logo became one of the most recognizable icons in movie history. When Ghostbusters opened in June 1984 it burned through box office records, disproving the prevailing wisdom that a big-budget comedy headlined by television actors could not compete with the likes of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. The film went on to gross more than $230 million in the United States alone, easily earning back its $30 million budget. When summer turned to fall, the film continued to pick up steam as millions of American children donned Ghostbusters costumes for Halloween. By Christmas, Venkman-, Stantz-, and Spengler-themed toys were all the rage—much to the delight of the stars’ accountants. “I remember during The Blues Brothers Dan had been down on doing a lot of merchandising,” Harold Ramis later remarked. “He would say, ‘I don’t want to be on every lunchbox in America.’ Well, when it came time for Ghostbusters his tune had changed, and he said, ‘Now I do want to be on every lunchbox in America.’ And we were.”

For Murray, the phantasmagoric success of Ghostbusters was a somewhat mixed blessing. He was now the most popular comic actor in Hollywood (at least until Beverly Hills Cop dropped later that year). But the film’s box office prowess did little to boost the fortunes of his true labor of love, The Razor’s Edge. It opened to harshly negative reviews and a mostly puzzled audience reaction in the fall of 1984. And while Murray the performer was now at peak demand, Murray the private citizen found himself melting under the glare of an exponentially higher level of fame. Tired of being stopped on the street by fans, he holed up in his New York apartment, didn’t cut his fingernails for ten weeks, and grew a salt-and-pepper beard that made him “look like a malamute/husky cross.” The mountain man look lasted only about a month, but by the end of the year Murray had fled to France to escape the spotlight and consider the next phase of his career. He would not star in another film for four years.

NEXT MOVIE: Nothing Lasts Forever (1984)

GHOSTBUSTERS II

DIRECTED BY: Ivan Reitman

WRITTEN BY: Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis

RELEASE DATE: June 16, 1989

FILM RATING: **

MURRAY RATING: **

PLOT: The Ghostbusters reunite to stop a seventeenth-century sorcerer from returning to life and resuming his reign of evil.

STARRING BILL MURRAY AS: Peter Venkman, ’Busters frontman

“Why did I make that movie?” Murray wondered aloud just seven months after the release of this unnecessary sequel to the 1984 hit. After five years of saying no to Ghostbusters II (“I don’t think there’s enough money to make me do it,” he declared in a 1984 interview), he finally acquiesced after a two-hour powwow with director Ivan Reitman, costars Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis—and their representation.

“The clever agents got us all together in a room,” Murray said afterward, “and we really are funny together. I mean they are funny people—Harold and Danny and myself… . And we were just blindingly funny for about an hour or so. And the agents, there was just foam coming off of them. And so they had this pitch and Danny and Harold had already concocted some sort of story idea, and it was a story, it was a good story. I think I had even already read one or two that Danny rolled out before that, but this one was a good one. I said, ‘Okay, we can do that one.’ It was just kind of fun to have all of us together.”

At first, that sense of fun seemed to translate to the screenplay, which Aykroyd and Ramis once again cowrote. “It returns the story to a human scale,” Murray told an interviewer before shooting began, “with subtlety and no silly explosions at the end. Like Scrooged, it’s a story about innocence restored, and good values, and the power of faith in ordinary people.” Like Scrooged, however, Ghostbusters II was fatally undermined by a director—Reitman—who preferred “silly explosions” and special effects to the character-driven comedy that attracted Murray to the project.

“It didn’t end up the way it was presented,” Murray explained after Ghostbusters II opened to decidedly mixed reviews. “The special effects guys took over. I had something like two scenes—and they’re the only funny ones in the movie.” To be fair, Murray’s Peter Venkman character has more than two scenes, although he doesn’t dominate the action the way he did in the original. The attempt to give more screen time to Aykroyd, Ramis, and Rick Moranis did prove somewhat successful. Ghostbusters II is more an ensemble piece and less a showcase for Murray’s talents. But the long, loud, enervating sequel doesn’t do nearly enough to distinguish itself from the first movie. For that, Murray placed the blame squarely on Reitman’s shoulders.

“It’s hard, it’s really hard to make a sequel, no matter how sincere you are,” Murray mused. “Somehow the directors take over from the writers and the comedians, and the thing ends up being a lot more action than comedy. Action is a lot easier to direct than comedy.” For his part, Reitman faulted the deficiencies of the script. “It didn’t all come together,” he told Vanity Fair in 2014. “We just sort of got off on the wrong foot story-wise on that film.” Rick Moranis cited unrealistic public expectations: “To have something as offbeat, unusual, and unpredictable [as] the first Ghostbusters, it’s next to impossible to create something better,” he said. “With sequels, it’s not that the audience wants more of something; they want better.”

Ghostbusters II was definitely not better, although it’s not nearly so bad as its creators remember. It grossed more than $215 million and raised hopes for a third installment that have so far gone unrealized, thanks largely to Murray’s distaste for repeating himself—unless he’s making a Garfield sequel, in which case, all bets are off.

NEXT MOVIE: Quick Change (1990)

GHOSTBUSTERS III

Over the decades, Murray has made it clear he has no interest in appearing in a proposed third Ghostbusters movie. He has gone out of his way to belittle the efforts of Harold Ramis and others to revive the franchise, dismissing various rumored storylines as “ridiculous,” “a crock,” and “not the way I would have gone.” He reportedly put down one Ghostbusters III script after reading just twenty pages. “It didn’t touch our stuff,” Murray groused. During a 2010 appearance on Late Show with David Letterman, Murray called the prospect of starring in a third Ghostbusters “my nightmare.” When Letterman asked if he’d participate in the film at all, Murray replied, “I told them if they killed me off in a first reel, I’d do it.” In 2014, Murray gave his blessing to a possible all-female reboot of the franchise, to be directed by Freaks and Geeks creator Paul Feig. “I’m fine with it,” he said. “I would go to that movie, and they’d probably have better outfits, too.”

“NO ONE WANTS TO PAY MONEY TO SEE FAT, OLD MEN CHASING GHOSTS!”

GHOSTBUSTERS: HELLBENT

See Ghostbusters III.

GHOSTBUSTERS: THE VIDEO GAME

Along with the other three original Ghostbusters, Murray did vocal work for this 2009 Atari video game based on the 1980s film franchise. Atari promoted the game as if it were the second sequel to the original film, hyping the supposed creative contributions of Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis. But Ramis told the New York Times their input was minimal. “They were happy to have our involvement at all,” Ramis said. “The crassest way I can put it is that they couldn’t have paid us enough to give it the time and attention required to make it as funny as a feature film.” Murray reportedly had a ball donning the figurative jumpsuit for the first time in twenty years. “That was fun,” he said afterward. “I’m not really a game guy, but I enjoyed recording it. It was funny. I liked being the guy [Peter Venkman] again.” He had such a good time, in fact, that he admitted to sauntering out of the New York recording studio singing Ray Parker Jr.’s Ghostbusters theme song. According to Murray, one of the locals “gave me this really pathetic look and shouts over at me: ‘Hey man, get over it will you? That was a long time ago, okay?’”

GILLIAM, TERRY

Murray is an admirer of the brilliant, mercurial director of Time Bandits and Brazil. He was reportedly offered a part in Gilliam’s 2013 sci-fi dystopia The Zero Theorem but turned it down in order to finish work on The Grand Budapest Hotel. “Terry’s a fun guy to hang out with,” Murray told the Sunday Times. “His stuff doesn’t always work for me, but it’s not for lack of trying. He really throws it out there.”

“IF I HAD A PINT OF TERRY’S BLOOD, I WOULD GET SOME SHIT DONE.”

GLAZER, MITCH

Screenwriter and producer who has collaborated with Murray on numerous films, including Mr. Mike’s Mondo Video, Scrooged, and Passion Play. A onetime music journalist, Glazer first met Murray in 1977 on the introduction of John Belushi, whom he’d recently profiled in Crawdaddy magazine. Glazer and Murray have remained friends ever since. Since the early 2000s, when Murray fired his agents and cut off most communication with the Hollywood film community, Glazer has also served as one of the actor’s informal conduits to the outside world. Producers often pester Glazer with calls to his home phone, asking him to pitch their projects to Murray. “I’m like an unpaid manager,” Glazer told Entertainment Weekly.

GLIMPSE INSIDE THE MIND OF CHARLES SWAN III, A

DIRECTED BY: Roman Coppola

WRITTEN BY: Roman Coppola

RELEASE DATE: February 8, 2013

FILM RATING: *½

MURRAY RATING: *

PLOT: Fantasy sequences illuminate the inner life of a loathsome graphic designer.

STARRING BILL MURRAY AS: Saul, business manager and would-be libertine

Murray has a small, underwritten supporting role as the boon companion of a scuzzy 1970s album cover designer in this self-indulgent admixture of Boogie Nights and All That Jazz. If Federico Fellini and Wes Anderson had a baby, and that baby had no talent, the movie he produced might have been A Glimpse inside the Mind of Charles Swan III.

A vile, misogynistic car wreck of a film “directed” (it might be more accurate to say “perpetrated”) by Francis Ford scion and frequent Anderson collaborator Roman Coppola, Swan was constructed as a showcase for a post-meltdown Charlie Sheen. But all it does is showcase how far he has fallen. Outfitted in tinted aviator glasses and a shaggy ’70s toupee, Sheen gives an abysmal performance as a character so irredeemably dickish he can only have been painted from real life. The rest of the cast consists of called-in favors by the well-connected writer/director. Anderson regular Jason Schwarztman debases his personal brand as Swan’s reprehensible Jewfro’d best friend. Murray, who worked with Coppola on Moonrise Kingdom and The Darjeeling Limited, showed his passionate commitment to the screenwriter’s sophomore directorial effort by arriving on set at the last possible minute. “Bill gave me the impression he was interested,” Coppola told the Times of London. “So I thought it was going to work out, but there was no sign of him and we needed to get him a costume and a hotel. Then he just showed up the day before.”

NEXT MOVIE: The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

GOLF

“Golf has been really kind to me,” Murray once said. “I’ve met a lot of extraordinary people through golf.” He has described the sport’s appeal as rooted in the unwritten rules by which players score themselves. Golf, he said, is “a game of self-report [with] codes of behavior and honor about it.”

“EVERY YEAR I SAY I’M GONNA PLAY MORE. BUT THEN A MOVIE COMES ALONG, AND I CAN’T GET SERIOUS ABOUT GOLF.”

Murray developed his love of golf as a child on the streets of Wilmette, Illinois. He and his brothers fashioned a makeshift golf course along a twenty-foot-wide parkway near their house. The “holes” were trees and telephone poles. When the boys’ shots went awry, they could count on the nuns at the nearby Sisters of Christian Charity convent to retrieve them. “They would just show up at the door every once in a while with a bag of golf balls,” said Murray’s brother Ed.

In interviews, Murray has blamed his poor performance in school on his passion for golf. “I was on the golf course rather than being in lessons,” he once admitted. “I couldn’t really think of anything that interested me.” When he was fourteen, Murray worked as a standard-bearer—a scoreboard carrier—at the Western Open, held at the Tam O’Shanter Golf Course, just outside Chicago. He had an up-close view of a thrilling fight to the finish between Arnold Palmer and the eventual tournament winner, Chi-Chi Rodriguez.

GOODBYE POP 1952–1976

National Lampoon comedy album from 1975 on which Murray appears. The record features musical parodies of such pop and rock artists as Elton John, the Beatles, Helen Reddy, and Neil Young. Performers on the vinyl LP include Christopher Guest, Paul Shaffer, and Gilda Radner. Murray’s most memorable contribution is the soul spoof “Kung Fu Christmas.”

In August 2007, Murray was pulled over by Swedish police for driving a golf cart through the streets of Stockholm while under the influence of alcohol. The actor was in town attending the Scandinavian Masters golf tournament when he commandeered the cart, which was parked outside his hotel, and drove it to the Café Opera nightclub about a mile away. “I don’t hold any grudge against Bill Murray for borrowing our cart for a while,” said tournament organizer Fredrik Nilsmark. Although he refused to take a Breathalyzer test, Murray allowed police to draw a blood sample and signed a document admitting that he was driving under the influence. He later paid a fine and avoided jail time.

GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL, THE

DIRECTED BY: Wes Anderson

WRITTEN BY: Wes Anderson

RELEASE DATE: February 6, 2014

FILM RATING: ***

MURRAY RATING: ***

PLOT: A fey concierge maintains his dignity while contesting a bogus murder charge in a fictitious Alpine country.

STARRING BILL MURRAY AS: Monsieur Ivan, crisply efficient hotel concierge

“I didn’t have much to do with it,” Murray declared of his seventh feature for director Wes Anderson. “I just showed up and did what I was told.” An elegy to a vanished age of Old World refinement, The Grand Budapest Hotel is chock full of cameos from Anderson regulars, including Owen Wilson, Jason Schwartzman, and Bob Balaban. Although Murray appears in only a couple short scenes, he manages to leave a mark nonetheless. Playing the hirsute leader of the Society of the Crossed Keys, a secret intelligence-gathering agency made up of fastidious European hotel concierges, he takes the concept of customer service to a whole new level.

“Bill’s role is a small part—but it’s very important,” Anderson told Rolling Stone. “He’s the head man of this secret society that is immensely important to the story. It was one of those moments that I decided I wanted to save Bill for this very quick but critical secret mission at the climax of the story. Even with just a few minutes of screen time, he truly steps right up to it and is someone that I can always rely on.”

As usual, it was Anderson’s idiosyncratic writing that attracted Murray to the project. “When I first read the script, I went ‘Holy cow, this is crazy!’” the actor told the Independent. Elsewhere, he likened The Grand Budapest Hotel to “a Times Square billboard dropped on your head. It’s amazing.” While perhaps not quite as mind-altering as Murray made it seem, this dapper little jewel box of a movie is one of Anderson’s more engaging efforts. That is thanks largely to the winning performance of Ralph Fiennes in the lead role and the lavish production design, including some of the most formidable facial hair committed to film since the 1970s.

Murray sports an elegant walrus mustache in the film, a far cry from the bushy look he showed up with to the set. “[Wes] wanted me to ask everybody in the cast who could to grow anything they could,” said hair and makeup designer Frances Hannon, Murray’s personal stylist dating back to 1997’s The Man Who Knew Too Little. “So I asked them to grow full beards and moustaches so that I could cut the shape in that Wes would want. Then Wes and I would get together with the actor—usually the night before they were to be on camera—and the three of us would discuss the references and inspirations and then we’d start cutting it and adjusting it. Bill, for example, came in and he had grown a full beard and this wonderful mustache that didn’t look anything like he did in the film. We went for the biggest one—you have to start big and then scale back.”

NEXT MOVIE: The Monuments Men (2014)

GRAND HOTEL ET DE MILAN

This five-star luxury hotel in Milan, Italy, is one of Murray’s favorite hotels in the world.

GRANT, CARY

Murray is a big fan of this effortlessly elegant Old Hollywood leading man, whom he impersonated in a 1977 Saturday Night Live sketch. “He was able to make being suave and debonair seem so natural,” Murray once said. “He moved so elegantly. He moved so gracefully. Everything he did. He gets a suit out of the closet in North by Northwest, you’re like ‘Wow, look at that man get that suit out of the closet.’ It’s breathtaking.”

Murray had a brief encounter with Grant while having dinner with his agent in the 1980s. “I was a movie star, a big shot, in my mind,” Murray remembered later. “There across the restaurant was Cary Grant. I was gobsmacked. It was everything I could do to not get up and walk over to his table. But I didn’t. I just held it together. And as he left the restaurant, he gave me a look that said, ‘That was cool. I know what you were doing. I know what you felt. And you sat here and didn’t do it. And that was cool.’ I thought, ‘I did the right thing.’ Later I met someone who told me, ‘Yeah, he knew you and he liked you. He thought your movies were good.’”

GROUNDHOG DAY

DIRECTED BY: Harold Ramis

WRITTEN BY: Danny Rubin and Harold Ramis

RELEASE DATE: February 12, 1993

FILM RATING: ****

MURRAY RATING: ****

PLOT: A misanthropic TV weatherman must relive the same day over and over until he learns how to cultivate benevolence toward others.

STARRING BILL MURRAY AS: Phil Connors, meteorologist for WPBH-TV 9 in Pittsburgh

In the annals of high-concept cinema, Groundhog Day stands alone. Its very title has entered the popular lexicon, invoked by hack writers everywhere as universal shorthand for “that thing that repeats itself over and over.” It is also one of the principal rune texts in the Murray canon. Murray has called his performance in this movie “probably the best work I’ve done” and Danny Rubin’s original screenplay “one of the greatest conceptual scripts I’ve ever seen.” Although the film was denied a single major award nomination, it is now regularly included on lists of the best fantasy and romantic comedy films of all time. Groundhog Day is “romantic without being nauseating,” Murray once said, “which is what we’re all looking for—romance without nausea.”

Yet it almost never came to be—at least, not with Bill Murray in the lead role. Director Harold Ramis was reluctant to cast his old friend after an unpleasant experience working with him on their previous film together. “Bill Murray was not at the top of my list,” Ramis told GQ. “He’d been getting crankier and crankier. By the end of Ghostbusters II, he was pretty cranky. I thought: Do I want to put up with this for twelve weeks?” The part of Phil Connors was originally offered to Michael Keaton, who turned it down because he “didn’t get it.” Tom Hanks was also considered, but he considered himself too nice for the role of the glib, womanizing weatherman. In retrospect, it seems almost blasphemous to imagine anyone else playing Connors, so fully committed was Murray to what would be a career-defining performance.

Before shooting began, Murray and Danny Rubin collaborated closely on improvements to the latter’s screenplay. They spent several weeks holed up in an office in New York City fine-tuning story elements between pick-up basketball games. At one point, at the insistence of the studio, a gypsy curse sequence was inserted at the beginning of the film to set the time loop plot in motion. But Murray preferred Rubin’s original scenario, which offered no explanation for the supernatural premise.

The star and the screenwriter also made a Groundhog Day 1992 road trip to Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, the setting of the film, where they sought inspiration from the locals. “We got to the only hotel in the town,” Murray told the Guardian. “I woke up at five a.m. and took a shower. The water was freezing cold. I went downstairs and said that there was no hot water. And the woman behind the counter said, ‘Oh, of course, there wouldn’t be any hot water today. Today is the only day in the year that the hotel is even close to full.’” That scene wound up going in the finished film.

In the end, Punxsutawney was abandoned as a location in favor of Woodstock, Illinois, a town close to the Chicago homes of Ramis and Murray. The shoot took place during one of the coldest winters anyone there could remember. On his first day on the set, Murray bought coffee and danish for the freezing crew. From then on, Murray prepared for his performance by watching the Weather Channel and trying to predict the bone-chilling climatic conditions on the set. “I went outside every day and guessed what was going to happen when I got there,” he said.

“I’M NOT JUST GONNA LOSE WEIGHT AND FLOSS, I’M GONNA LIVE.”

Complicating the already arduous winter shoot was Ramis’s insistence on shooting and reshooting the same scenes in different weather conditions, so that he could assemble the footage in the proper sequence in the editing room. This led to some inspired moments of improvisation, as in the scene where Murray’s character bear-hugs his nemesis, Ned Ryerson, played by Stephen Tobolowksy. Reshoots were also a consequence of nearly continuous rewrites. According to Tobolowksy, Ramis and Rubin threw out nearly half of Rubin’s original script while on the set: “We were getting pages just hot off the press while we were shooting this,” Tobolowsky told the website Epoch Times. “The way the movie was originally … Bill had a series of odd events, and then at the end he got bored and killed himself and then woke up and time started again. [Instead] they cut out the last third of the movie, moved the suicide up, and added the whole last part of the movie where he’s taking piano lessons, and he saves the woman with the flat tire and saves the boy from the tree.” Excised from the movie at various points were a scene in which Phil Connors destroys his hotel room with a chainsaw and several scenes involving the groundhog (which reportedly bit Murray a couple times during filming). As a result of the changes, Groundhog Day went from being what Tobolowsky called “a mediocre Bill Murray movie … a rowdy comedy with Bill being rowdy” to “a great film … about healing and making the choice to survive and to heal.”

Not all the tweaks met with Murray’s approval. “I thought there was a lot of overwriting,” he declared in 2014. “And I held Harold responsible for that.” By all accounts, Murray was at his absolute surliest during the making of this film. “Bill was not easy to work with,” Tobolowksy admitted. “If I had been on my first movie, he would have brought me to tears more than once.” Most famously, Murray refused to shoot the film’s climactic scene—in which Phil Connors wakes up in bed with Andie MacDowell’s Rita Hanson, having escaped the time loop—until somebody told him whether he was still wearing the same clothes from the night before. When Ramis refused to take the bait, an assistant set decorator was forced to make the call on this crucial plot point.

Adding to the bad vibes was the fact that Murray’s first marriage was disintegrating around the time Groundhog Day was being shot. Part of the reason Danny Rubin was dispatched to babysit Murray during preproduction was to get him away from Ramis, who was sick of dealing with Murray’s temper tantrums. “They were like two brothers who weren’t getting along,” Rubin told the New Yorker. “And they were pretty far apart on what the movie was about.” In classic passive-aggressive fashion, Murray took out his anger at Ramis by showing up late to the set, berating members of the crew, and engaging in occasional outbursts of autodestruction. “Whoever was around had to take it from him,” Ramis later said. “Or he’d go back and trash his motor home. I’d say, ‘Well, now you’ve trashed your motor home. Good idea.’” After weeks of being “irrationally mean and unavailable,” in Ramis’s view, Murray finally stopped speaking to the director altogether. They would remain estranged for more than twenty years.

Although critics responded positively, Groundhog Day was not exactly a commercial triumph on its original release. Shortly after the film opened, a colossal blizzard buried much of the eastern half of the United States under a blanket of snow. “How could anyone go to the movies when they couldn’t even get out of their driveway?” Murray complained. “Two weeks later there was another ten inches of snow—same thing. So it wasn’t the box-office success it should have been.” Still, despite the agony he had gone through to get the picture made, Murray was proud of the work he had done and encouraged by the favorable notices he received for his performance. “That was sort of the turning point,” he later said. “That was the first time the New York press went, ‘Hey, wait a minute—this is a real movie here, not just that broad thing.’” One day that spring, Murray saw a caricature of himself in the New Yorker, depicting him emerging from the soil like the proverbial groundhog. “It was so cute and it was so great,” he said. “That felt good. It wasn’t an Academy Award, but it was somethin’ I liked a lot. It was more significant.”

NEXT MOVIE: Mad Dog and Glory (1993)

GUNG HO

During his mid-1980s sabbatical from Hollywood, Murray passed on the lead role in this 1986 comedy directed by Ron Howard. Michael Keaton ended up playing the part of Hunt Stevenson, the cocksure American foreman of a Japanese-owned auto plant.

GURDJIEFF, GEORGE IVANOVITCH

Mid-twentieth-century Greco-Armenian spiritual guru whose teachings Murray began to study in the 1980s. Gurdjieff’s quasimystical philosophical system, commonly called “the Work,” “the Fourth Way,” or “the Way of the Sly Man,” is based on the idea that human beings live their lives in a state of perpetual sleep, ruled by forces beyond their control. Only by “waking up” through the practice of Gurdjieff-approved awareness exercises can they achieve a state of true enlightenment and free will. In his Jazz Age heyday, Gurdjieff ran an institute near Paris where he would unexpectedly create unorthodox events designed to startle his disciples into consciousness in the same way that Zen masters whack meditating students over the back with a stick.

Dismissed by some as a crackpot, Gurdjieff developed a cult following among artists, intellectuals, and wealthy socialites. His esoteric teachings are still followed by a small and secretive coterie of adherents. Murray first began studying Gurdjieff in earnest during his Parisian sabbatical from filmmaking in the mid-1980s. Every January 13, Gurdjieff’s followers gather to commemorate his birthday with elaborate vodka toasts and performances of the Epic of Gilgamesh. According to eyewitness accounts, Murray has attended at least one such celebration. He has also taken part in so-called ideas meetings, during which passages from Gurdjieff’s masterpiece Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson are read and discussed.

In a 2009 interview with GQ magazine, Harold Ramis attributed some aspects of Murray’s notoriously surly personality to his study of the spiritual figure. “Gurdjieff used to act really irrationally to his students, almost as if trying to teach them object lessons,” Ramis observed. “Bill was always teaching people lessons like that. If he perceived someone as being too self-important or corrupt in some way that he couldn’t stomach, it was his job to straighten them out.” According to Nothing Lasts Forever director Tom Schiller, also a Gurdjieff devotee, Murray’s connection to the Mediterranean mystic also accounts for his party-crashing and photo-bombing antics of recent years. “Bill fits Gurdjieff’s description exactly,” Schiller says. “At any moment, anywhere, he can engage perfect strangers in hilarious and spontaneous acts of humor that a mere mortal could never get away with.”

GUYS, THE

In one of his rare forays onto the dramatic stage, Murray played a New York City firefighter haunted by his memories of September 11 in this 2001 play by Anne Nelson. Sigourney Weaver starred as the newspaper editor who helps him compose eulogies for his fallen comrades. The Guys opened at the Flea Theater, just a few blocks from Ground Zero, in December 2001. In an interview, Murray described the experience as cathartic and credited his costar with giving him the strength to get through it. “It was just something that had to be done,” he said. “It was so hard going out there night after night with a situation that was so raw. She never lost sight of the moment onstage, because she kept focus, and that kept things going right. It helped me keep on track, too.” Although Murray left the production shortly after opening night, replaced by Bill Irwin, it was not because of poor notices. Variety found the play “dramatically a bit on the dull side” but praised Murray’s performance as “utterly artless and unactorly, and very touching in its honesty.”

The Connected Wisdom of

Bill Murray and G. I. Gurdjieff

“Only by beginning to remember himself does a man really awaken.” —Gurdjieff, from his essay “Awakened Consciousness” |

“Whatever the best part of my life has been, has been as a result of that remembering.” —Murray, in an interview with the New York Times |

“Only he who can take care of what belongs to others may have his own.” —Gurdjieff’s Aphorism #20 |

“I think if you can take care of yourself and then maybe try to take care of someone else, that’s sort of how you’re supposed to live.” —Murray, during a 2009 appearance on CNBC’s Squawk Box |

“A man may be born, but in order to be born he must first die, and in order to die he must first awake.” —Gurdjieff, In Search of the Miraculous |

“It’s not easy to really engage all the time. It’s so much easier to zone, to get distracted, to daydream.” —Murray, to interviewer Charlie Rose in 2014 |

“I love him who loves work.” —Gurdjieff’s Aphorism #15 |

“I don’t want to have a relationship with someone if I’m not going to work with them.” —Murray, to GQ magazine in 2010 |

“He who has freed himself of the disease of tomorrow has a chance to attain what he came here for.” —Gurdjieff’s Aphorism #28 |

“What if there is no tomorrow? There wasn’t one today!” —Murray, as weatherman Phil Connors in Groundhog Day |

“All that men say and do, they say and do in sleep. All this can have no value whatsoever. Only awakening and what leads to awakening has a value in reality.” —Gurdjieff, from “Awakened Consciousness” |

“You’re unconscious most of the time. Not out cold, but you’re unconscious. Lights on, nobody home. If you come back, ‘Oh, there I am again.’ All of a sudden, you’re looking at yourself, like, ‘Where am I now? What was I thinking? What am I feeling? What’s my body doing?’ Usually, I have a pang of remorse or a reminding, like, ‘Oh, here I am again. How was it I wanted to be living?’” —Murray, in an interview with the Detroit Free Press |

“One of the best means for arousing the wish to work on yourself is to realize that you may die at any moment.” —Gurdjieff’s Aphorism #33 |

“I’ve got a moose head on the wall. The biggest moose head I’ve ever seen. It’s a sobering thought that something that big can die.” —Murray, describing the decor in his New York City apartment, in 1981 |

On a brisk fall day in 2012, Murray visited New York City to check out the recently completed Franklin Delano Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, located at the southern tip of Roosevelt Island. After getting a sneak peek at the FDR memorial, which was not yet open to the public, he found himself inexorably drawn to a beer-league kickball game being played on a nearby stretch of grass. Kickballers were surprised by the apparition of a slightly disheveled older man, wearing blue cutoffs and a loose-fitting flannel shirt, who suddenly and without warning jumped into their game. “We just figured he was someone’s dad on the other team and kept playing,” one of the players said later. Taking a turn at the plate, Murray launched a booming single but was chased back to first when he attempted to go for two. It was at that point that the other players realized who he was. After getting erased on an ensuing double play, Murray jogged around the bases high-fiving everyone, bear-hugged a player’s mother, posed for a team photo, and then went home.