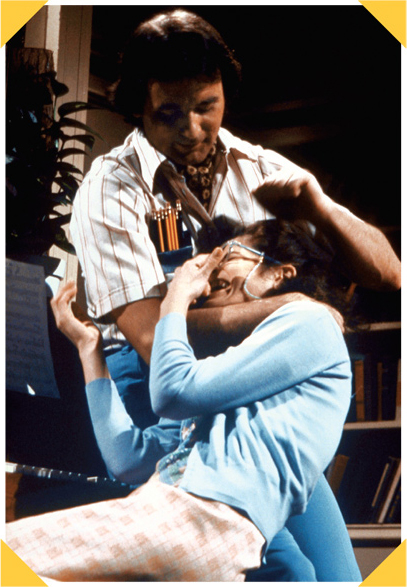

RADNER, GILDA

Murray had a tumultuous on-again, off-again romantic relationship with his National Lampoon Radio Hour and Saturday Night Live castmate, with whom he collaborated on the popular Nerds sketches. “I’ve always had a thing for funny girls,” he once declared. “Gilda was the greatest laugher and she was funny herself. To me that was incredibly attractive.” By all accounts, their liaison had ended by the early 1980s, when Radner married guitarist G. E. Smith and Murray wedded Mickey Kelly. The creator of such breakout characters as Baba Wawa, Emily Litella, and Roseanne Roseannadanna, Radner was known as the heartbreaker among the early SNL cast. “Anyone that knew Gilda fell in love with her,” Murray once said. “She was really something.” In interviews, he has credited Radner—the daughter of a prominent Detroit hotelier—with teaching him the importance of saying no to people. “Gilda had money from her family, and when she went in to talk about a job, she didn’t need it. And there’s something about work, just like there’s something about romance, that if you don’t have to have someone, you’re more desirable.”

RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK

Murray was one of several actors considered for the role of Indiana Jones in this 1981 blockbuster. Tom Selleck, Nick Nolte, Steve Martin, Chevy Chase, Tim Matheson, Jack Nicholson, and Jeff Bridges were also up for the part, which eventually went to Harrison Ford.

RAIN MAN

Dustin Hoffman won an Oscar for his portrayal of autistic savant Raymond Babbitt in this 1988 film. But according to screenwriter Barry Morrow, Murray was offered the role first. In the original casting configuration, Hoffman would have played Raymond’s brother Charlie, the role played by Tom Cruise in the finished film.

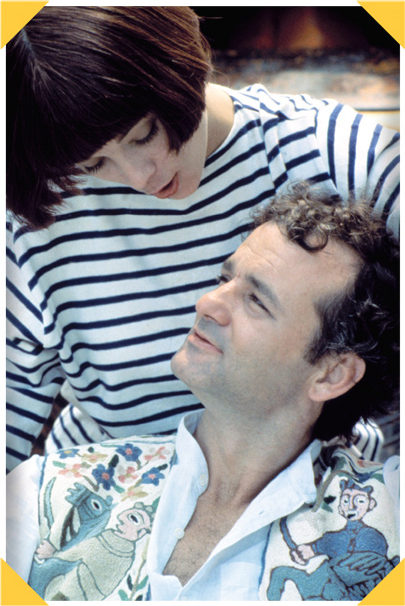

RAMIS, HAROLD

Curly-haired comic writer, actor, and director who collaborated with Murray on numerous projects over a twenty-year period beginning in the mid-1970s. A native of Chicago, Ramis attended college at Washington University in St. Louis. After graduation, he worked for seven months as an orderly in a mental institution. There he learned “how to speak to schizophrenics, catatonics, paranoids, and suicidal people,” an experience, he often said, that was perfect training for working with actors.

“HE JUST PUNISHES PEOPLE, FOR REASONS THEY CAN’T FIGURE OUT.”

Ramis first met Murray in 1968 at the introduction of Murray’s brother Brian. “Brian and I were in Second City together and he said, ‘Why don’t you come up and have dinner at my mother’s house?’” Ramis recalled in a 2010 interview. Along the way, they stopped off at the golf course where Murray operated a ninth-hole hot dog stand. Their paths would cross again a few years later in New York, when Murray joined the casts of The National Lampoon Radio Hour and the Off-Broadway revue The National Lampoon Show. Ramis was immediately struck by Murray’s electrifying stage presence. He repeatedly called Murray the best verbal improviser he had ever seen. The two eventually struck up a creative partnership that lasted through six feature films. “I always tell students to identify the most talented person in the room and, if it isn’t you, go stand next to him,” Ramis once said. “That’s what I did with Bill.”

Ramis has often been credited with helping to cultivate Murray’s 1980s big-screen persona—the sardonic slacker-trickster who charms his way out of precarious situations. “I had Bill’s voice down,” he told GQ. “When people would read something I’d written for him, they’d say, ‘That is so perfectly Bill Murray.’ Of course, the irony is that he’d read it and say, ‘Bullshit, I can’t say this.’” In a 2009 interview with the Onion’s A.V. Club, Ramis likened his creative bond with Murray to an alliance between great powers: “I could help him be the best funny Bill Murray he could be, and I think he appreciated that then.”

In time, however, Murray may have come to resent Ramis’s outsize role in his career. “Bill owes everything to Harold,” a mutual friend, producer Michael Shamberg, told the New Yorker, “and he probably has a thimbleful of gratitude.” The rift between the two men came to a head on the set of Groundhog Day in 1992. Creative differences centered on Ramis’s rewrites to Danny Rubin’s screenplay, as well as Murray’s belief that Ramis was becoming too much of a “mogul,” led to a more or less permanent cold war between the two men that lasted until Ramis fell mortally ill with autoimmune inflammatory vasculitis in late 2013.

Over the last two decades of his life, Ramis made repeated efforts to patch things up with Murray. But except for brief exchanges at a wake and a bar mitzvah, the two men never spoke to each other. Ramis remained puzzled by his former friend’s refusal to engage. “I have no clue” why Murray cut him off, he once said. “And because it’s unstated, it sends me to my worst fears. Did he think I was weak? Or untrue? Did I betray him in some way? With no clue or feedback from him, it’s this kind of tantalizing mystery. And that may be the point.”

Only in Ramis’s final hours did Murray make the decision to reconcile with him. “He became ill and I thought, ‘Well, this is stupid,’” Murray told an interviewer for Grantland. Shortly before Ramis passed away, Murray visited him unexpectedly at his home in the Chicago suburbs to say goodbye. After his death, Murray issued a statement to the press through his lawyer, David Nochimson. It read in full: “Harold Ramis and I together did The National Lampoon Show off-Broadway, Meatballs, Stripes, Caddyshack, Ghostbusters, and Groundhog Day. He earned his keep on this planet. God bless him.”

RASCALS, THE

Blue-eyed soul quartet of the 1960s, best known for their hits “Good Lovin’” and “Groovin’.” In 2010, Murray attended a reunion concert by the band, which he called “maybe the best thing I’ve ever seen.”

RAZOR’S EDGE, THE

DIRECTED BY: John Byrum

WRITTEN BY: John Byrum and Bill Murray

RELEASE DATE: October 19, 1984

FILM RATING: **

MURRAY RATING: **

PLOT: A battle-scarred World War I veteran abandons his comfortable life in America to go on a vision quest through Paris and India.

STARRING BILL MURRAY AS: Larry Darrell, burned-out World War I ambulance driver

According to Hollywood legend, actor Tyrone Power was so transfixed by W. Somerset Maugham’s 1944 novel The Razor’s Edge that he pulled an audacious power play in order to get a movie version made. Burned out after years of cranking out Zorro movies, Power agreed to play the masked swordsman one last time if Twentieth Century Fox would let him star as Larry Darrell, Maugham’s idealistic hero, in a big-screen adaptation of the novel. The story is apocryphal—Power played Zorro only once, and that was in 1940—but it illustrates the powerful hold a prestige project like The Razor’s Edge can exert over a young star wary of being typecast. Nearly forty years after Larry Darrell breathed new life into Tyrone Power’s career, Bill Murray successfully maneuvered Columbia Pictures into giving him a crack at the role, one he hoped would establish him once and for all as a bankable dramatic actor.

In the early 1980s, Murray became friends with John Byrum, a young director who had grown up about a mile from Murray’s hometown. In March 1982, shortly after Murray’s wife gave birth to their first child, Byrum sent Murray a copy of The Razor’s Edge to keep him occupied during her recovery. After reading the first fifty pages, Murray had an epiphany: he was Maugham’s disillusioned seeker and he wanted to make the character his first great dramatic role. The next night, he called Byrum at four in the morning. “This is Larry, Larry Darrell,” Murray said when the director picked up the phone. The two friends began spitballing plans to bring The Razor’s Edge back to the screen.

Murray and Byrum spent the next year working on the script. At Murray’s suggestion, they set off on a Darrell-like road trip across America, writing up scenes in bars, bus stations, and restaurants they stopped in along the way. “We went to northern California ashrams and nudist colonies, visited strange religious cults with aerobic classes,” Byrum later told Film Journal. “We did a lot of our best writing in a car driving across Nebraska.”

Securing studio backing for the unusual venture proved surprisingly easy, once Murray realized he could leverage his participation in the new paranormal comedy that Dan Aykroyd was writing for him. “As soon as people heard about Ghostbusters, every studio wanted it,” Murray said. “But I still wanted to do The Razor’s Edge. Finally Dan said, ‘Tell whoever wants Ghostbusters that they have to take The Razor’s Edge, too.’ We didn’t have to tell them. They figured it out real quick. You didn’t have to be a rocket scientist to see what the deal was going to be. Finally the people at Columbia said, ‘We’re really nuts about that Razor’s Edge. Now about this other movie …’”

“PEOPLE SAID I WAS VERY COURAGEOUS MAKING THAT MOVIE. SURE. SO’S SETTING YOURSELF ON FIRE. AFTER THAT MOVIE, I FELT RADIOACTIVE.”

Filming took place on location in France and India in the summer of 1983. Murray’s wife Mickey and infant son Homer joined him for the first leg of the shoot. “Nobody wanted to come to India,” he said. “They all thought it was pretty good to be in Paris spending money, but when we said, ‘Well, now we’re going to go eat dried dog and yogurt,’ they said ‘No, we think we’ll go home.’” Consistent with his view that Razor’s Edge was a film he had been called to make, Murray took no salary for acting in it (though he did get $12,000 for cowriting the script). Principal photography wrapped up in early October, just in time for Murray to report to the Ghostbusters set in New York City.

After viewing a rough cut of The Razor’s Edge that fall, Murray waited nervously for the audience’s verdict. Originally scheduled to come out before Ghostbusters, the film was held back until the following autumn, allowing the negative buzz to build. “I don’t know what my fans are going to think,” Murray told an interviewer in anticipation of the release. “It’s definitely not what they’re used to from me.”

He was right to be worried. The Razor’s Edge opened in October 1984 to harshly negative reviews. The New York Times called it “slow, overlong, and ridiculously overproduced.” “Huge chunks of hackneyed drama are interspersed with Murray doing Murray,” carped the reviewer for the New York Daily News. J. Hoberman of the Village Voice called Murray’s Larry Darrell “a leering goofball, even in deepest Tibet.” Murray’s earnest attempt to portray a spiritual seeker was fatally burdened by his past life as a clown, Hoberman wrote. “When he finally dons the saffron robes, he’s like a conehead who’s lost his cone.” The public wasn’t convinced either. “I remember arriving a few minutes late on the opening day,” John Byrum recalled. “They were streaming out of the theater and shouting to people waiting in line for the next show: ‘Don’t waste your money, it isn’t funny!’”

Watching The Razor’s Edge today, it is hard to justify such an angry response. True, the movie is excruciatingly slow and ponderous—but no more so than such “masterpieces” of the era as Chariots of Fire or Gandhi. It deserves props for its ambition, though it is weighed down by a number of terrible performances (the two female leads, Catherine Hicks and Theresa Russell, are especially dreadful) and by Murray, who thrives in the early comedic scenes but seems totally out of his element moping around World War I–era Paris. His attempts to convey Larry Darrell’s spiritual detachment come off as mere blankness—an affect he would perfect later in his career but had not mastered at this point in his development as an actor.

What makes The Razor’s Edge so fascinating is the window it opens onto Murray’s mind-set at this stage of his life. Having turned thirty, and newly minted as one of the rising stars in Hollywood, he was struggling with the demands of fame and family. Shortly before he started work on the project, his friend John Belushi died of a drug overdose; Caddyshack screenwriter Doug Kenney had lost his life just two years earlier. Razor’s Edge executive producer Rob Cohen attributed Murray’s obsession with making the film to the changes going on in his personal life: “He got married. He had a child. There were the deaths of some friends. All these things came up on him, and I believe he began to think a little more deeply about life.”

Murray explained the project’s appeal in similar terms: “The story I got was of a guy who sees that there’s more to life than just making a buck and having a romantic fling. I’d experienced that, and I knew what that was, so I had my own ideas about how it played… . There are things in it that came from our own lives or that were happening to us while we were doing the movie.” Indeed, some of the lines Murray wrote for Larry Darrell seem like they could have come out of his own mouth circa 1984. “This isn’t the old Mr. Sunshine,” Larry declares at one point, in what could have been a warning to moviegoers expecting another Stripes or Caddyshack. Speaking about the hollowness of material success, Larry says: “I’ve got a second chance, and I’m not gonna waste it on a big house, and a new car every year, and a bunch of friends who want a big house and a new car every year!”

When The Razor’s Edge tanked, Murray was left to pick up the pieces. In interviews conducted after the film’s release, he conceded that it had been a mistake to do it as a period piece, suggesting that a Larry Darrell story set in the aftermath of Vietnam might have had more appeal for modern audiences. “I kind of deluded myself that there would be a lot of interest” in the film, he said. “I made a big mistake.” With the passage of time, he came to see it as a noble error: “People say that was a flop of a movie. They don’t know what a flop is. A flop is where nothing is good. I loved the process of making it. The fact that it wasn’t a commercial hit … I’m a half-smart guy. I can see where a movie about a man’s spiritual search might not do as well as Home Alone.” But he also bristled at the pasting he had taken from critics, accusing them of bias against comedians taking on dramatic roles: “It angers people, like you’re taking something away from them. That’s the response I got. I thought, ‘Well, aren’t we all bigger than that?’ I wasn’t shocked by it, but I thought that the professional critics would be able to say, ‘Okay, we shouldn’t rule this out, because the guy normally does other stuff.’”

Murray was able to recover from the disappointment of The Razor’s Edge, though friends report that he did not react well at the time. “I think Bill was completely trashed by the film’s failure,” said John Byrum. “It was his first serious film and he wanted to extend himself as an actor. The critics and audiences wanted him to be the guy in Meatballs for the rest of his life.” In fact, Murray was so mortified by the burden of public expectations that he closed up shop, moved to Paris, and did not star in a Hollywood film for the next four years.

NEXT MOVIE: Little Shop of Horrors (1986)

REGIS COLLEGE

Jesuit college in Denver, Colorado, that Murray attended from 1968 to 1970. He later admitted that he chose the school because a couple friends were going there. Murray took only one acting class at Regis (now known as Regis University). “I thought it’d be a piece of cake and there were a lot of girls in it,” he said. “I knew I could act as good as these girls could, just by seeing them around the coffee shop.” His acting teacher was even more of a horndog than he was. “So long as you never looked funny at him while he was staring at a girl, you got a good grade. But I only hung in there for one semester. That was that.” Murray then enrolled in the premed program but was forced to drop out of school after he was arrested for marijuana possession while flying back to Denver from Chicago in September 1970. “I was not really college material,” he once confessed to an interviewer. “I didn’t know how to study, but I liked the lifestyle. You could dress any way you wanted. I was wearing pajamas and a sports coat to school and pajamas and loafers to formal events. College was terrible. I didn’t get it at all, but it got me out of the house.” Despite his misgivings, Murray returned to Regis for what would have been his twentieth class reunion, in 1992. He was spotted at the reception wearing a badge bearing the legend “Hi! I’m Bill Murray.” In July 2007, Regis awarded Murray an honorary doctorate in humanities. He accepted the degree wearing a suit jacket over a pair of pajama shorts.

“WHY SHOULD I SPEND MORE TIME ON YOUR COLLEGE GRADUATION THAN I SPENT ON MY OWN? I HAVE A DEGREE, FROM HIGH SCHOOL, BUT I’M A FUCKING MILLIONAIRE.”

REITMAN, IVAN

Slovak Canadian filmmaker who directed Murray in Meatballs, Stripes, and both Ghostbusters movies. In the early 1970s, Reitman worked as a theatrical producer in Toronto. In that capacity, he was instrumental in bringing The National Lampoon Show off-Broadway in 1975. He later likened the experience of working with Murray, John Belushi, Harold Ramis, and other Lampoon Show cast members to taking “an inspirational shower.” “I immediately knew I would have to make movies with them, that they would all be famous, that this was where comedy was going.” Of his subsequent collaborations with Murray, Reitman has said: “One thing I’ve tried to do as a director is show Bill as a human being. On Saturday Night Live, all you saw was this wacky sort of side, but he has a very warm, genuine quality. I think I brought out some glimpses of that.”

RELIGION

Murray was raised Roman Catholic and educated by nuns at St. Joseph School in Wilmette, Illinois. In early childhood, he developed his own personal form of spirituality. “When I was little, and alone, I used to sing songs to God,” he once said.

Although he maintains a nominal affiliation with the church, he no longer identifies as Catholic. In a 1984 interview, Murray talked about his faith: “I’m definitely a religious person, but it doesn’t have much to do with Catholicism anymore. I don’t think about Catholicism much.” He attributes his drift away from organized religion to the harsh discipline imposed by the nuns in his grade school: “You really get, you know, the fear of hell and confession and Mass and the sacraments. You get it real hard, but because it’s sort of by rote, sometimes the feeling of it is sort of lost to you.”

ROMANCE OF HAPPY VALLEY, A

Murray credits this 1919 silent film from director D. W. Griffith with convincing him to make better career choices. The story follows a young man who leaves his Kentucky farm to make his fortune in New York City. After several years, he returns home a wealthy man. But his father no longer recognizes him and hatches a plan to murder him and steal his money. The film ends on a happy note, with the family members reconciled and their imperiled farm saved from bankruptcy.

Murray first saw A Romance of Happy Valley at the Cinémathèque Française in Paris during his sabbatical from Hollywood in the mid-1980s. The film was presented with Russian subtitles, which Murray couldn’t understand, but it still managed to move him to tears. “This movie just destroyed me,” he told an interviewer. “And I thought ‘How the hell can you go make The Love Bug if you’ve seen this.’” In addition to inspiring him to seek out more meaningful projects, Happy Valley also prompted Murray to muse on what his life would have been like had he been born in the silent film era. “What would a guy like me do at that time? I wouldn’t be working in the movies. Without a tongue, who am I?”

ROMANTIC COMEDIES

Although he has been offered numerous plum parts, Murray has avoided making romantic comedies since Groundhog Day. “The romantic figure has to behave romantically even after acting like a total swine,” he has said. “It’s, ‘I’m so gorgeous, you’re going to have to go through all kinds of hell for me,’ and that isn’t interesting to me. Romance, like comedy, is very particular. There’s something about romance that if you don’t have to have someone, you’re more desirable.”

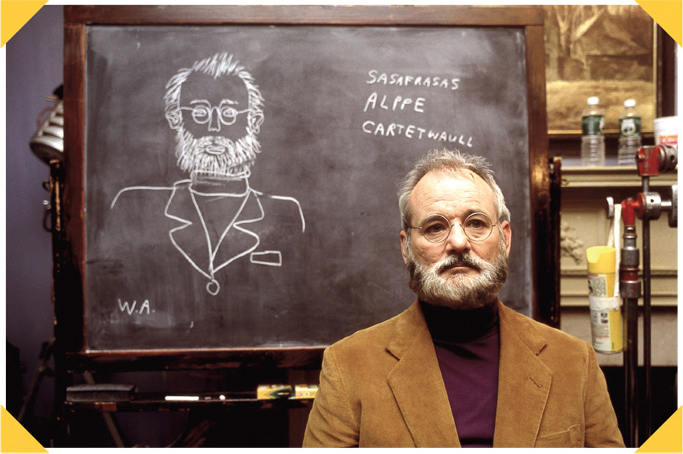

ROYAL TENENBAUMS, THE

DIRECTED BY: Wes Anderson

WRITTEN BY: Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson

RELEASE DATE: December 14, 2001

FILM RATING: ***

MURRAY RATING: **

PLOT: A family of eccentrics reconciles with its vagabond patriarch.

STARRING BILL MURRAY AS: Raleigh St. Clair, cuckolded neurologist

Wes Anderson to the rescue once again. After a year in which his talents were largely wasted in the sick-making Osmosis Jones and the slapdash Speaking of Sex, Murray filled his tank with hipster cred by appearing in Anderson’s twee family fable. The Royal Tenenbaums is not quite as good as Rushmore, and Murray’s role is not nearly as meaty. But he took the part sight unseen, without even reading the script, on the strength of his affinity for the young director. Proximity also had something to do with it. “We filmed in New York,” Anderson told Rolling Stone, “and as he didn’t live that far away, Bill thought that it would be fun to do it.” Another important consideration: Murray’s uncanny ability to grow a beard quickly, which allowed him to disappear into his role as the lugubrious neurologist Raleigh St. Clair. On the set, Murray became fast friends with Royal Tenenbaum himself, the seventy-year-old acting legend whose old New York City apartment he had once sublet. “Gene Hackman took a real liking to him during that shoot,” Anderson said. “They got along very well.”

NEXT MOVIE: Lost in Translation (2003)

RUSHMORE

DIRECTED BY: Wes Anderson

WRITTEN BY: Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson

RELEASE DATE: October 9, 1998

FILM RATING: ****

MURRAY RATING: ****

PLOT: A twee übermensch competes with a depressed millionaire for the affections of a morose widow.

STARRING BILL MURRAY AS: Herman Blume, sad-sack steel magnate

After failing to cast Murray in his debut feature, Bottle Rocket, director Wes Anderson finally snagged the White Whale for his sophomore effort. The delightfully idiosyncratic Rushmore marked a critical turning point in Murray’s career, as the dark, forlorn, yearning quality that had existed as an undertone in his characters finally came roaring to the surface. The era of “Sad Bill Murray” had officially begun.

To his credit, Anderson was among the first filmmakers to spot the potential for pathos in Murray. He and coscreenwriter Owen Wilson wrote the part of Herman Blume specifically for him. “I thought he’d be funny, and real,” Anderson explained. “And also there was a sort of a sadness about him.” As he had with Bottle Rocket, he sent the script for Rushmore to Murray with little expectation that he would even read it. But Murray was impressed by the precision of the writing and called Anderson to talk about the role. “Anybody that writes it that way knows exactly what they want to show,” he told the New York Times.

At the time, Murray was still reeling from a series of personal and professional setbacks—including his first divorce and the critical and commercial failure of The Man Who Knew Too Little—and was eager to tap that vein of disappointment in his work. “A lot of Rushmore is about the struggle to retain civility and kindness in the face of extraordinary pain,” he explained. “And I’ve felt a lot of that in my life. Movies don’t usually show the failure of relationships; they want to give the audience a final, happy resolution. In Rushmore, I play a guy who’s aware that his life is not working, but he’s still holding on, hoping something will happen, and that’s what’s most interesting.” Elsewhere, Murray admitted that he drew inspiration for his performance from the breakup of his marriage: “You’ve had to have really suffered to realize how badly someone can feel, not just for an act or an incident, but a wave, a time period of bad feeling, of low self-esteem.”

Murray agreed to work on the film for scale, or $9,000, plus a percentage of the profits. His standard salary at the time was a thousand times that amount, or $9 million a picture.

In his book The Wes Anderson Collection, Matt Zoller Seitz reveals that Murray might have taken a loss on Rushmore if Anderson had cashed the blank check Murray gave him to cover the cost of a $25,000 helicopter scene that the studio refused to pay for. Anderson ended up cutting the sequence from the film, but he was so touched by Murray’s gesture that he saved the uncashed check as a memento.

Anderson’s other memories of working with Murray all involve eating, drinking, and general merriment: an evening in a hotel bar in Los Angeles when “Bill took the place over and started dancing,” and the happy aftermath of a disastrous table read with the film’s inexperienced star Jason Schwartzman. “It didn’t go well at all,” Anderson told Rolling Stone. “We beat ourselves up over whether we should change the dialogue, but Bill said that the dialogue is why he signed on. A day later, Bill took us out to a restaurant where we ate chicken-fried steak. After that, everything was fine. I like to think that he was great in the role—but beyond that, he was the godfather of that film.”

NEXT MOVIE: Cradle Will Rock (1999)

RUTLES, THE

See All You Need Is Cash.

In August 2008, Murray helped kick off the annual Chicago Air and Water Show by jumping out of a plane two and a half miles above the city with skydivers from the U.S. Army Golden Knights parachute team. Murray managed to play air guitar and perform a brief hand jive before his chute deployed.

At the time, the fifty-seven-year-old actor was in the depths of a depressive spiral precipitated by his recent bitter divorce from his second wife, Jennifer Butler. “I was just dead, just broken,” he said of his mind-set that summer. Friends thought a bracing skydive might be good therapy for him. “They asked me on a day I didn’t care,” said Murray. “I didn’t even care if there was a parachute. Of course, by the time I got there I had had a few good days and I thought, ‘What am I doing?’” In a postdive interview with the Chicago Tribune, Murray described the experience as a mix of terror and exhilaration:

“Once you go, and you hit the air, all that’s gone. The physical sensation overwhelms your body. Overwhelms your mind. You can’t think anymore. You’re just in a washing machine of air. You’re trying to move your arms and move your hands. Meanwhile, you’ve got this guy on your back. And then he starts steering you. And they’re filming you, so you feel like, ‘Oh, I’m supposed to be funny now.’ When the chute opens, it’s not that ka-kunk thing you see in the movies. It’s just that the people you’re talking to or looking at just sort of drop through the bottom of the floor. Then it became extremely peaceful and really dreamy. I was like, ‘Hey, there’s Wrigley Field, can we go over there?’”