The first 10 chapters of this book dealt with microeconomic issues, that is, issues involving the performance of individual markets. Microeconomics seeks to answer questions like, “How much is produced and sold?,” “Is that amount efficient?,” and “Will intervention improve this outcome?” The second half of this book deals with macroeconomic issues. Macroeconomics, from the Greek root macro meaning “large,” deals with the performance of entire economies and studies issues such as economic growth, the total amount of production within an economy (usually called aggregate output), inflation, unemployment, trade, and the monetary system. The goal of a macroeconomist is to understand the mechanisms that drive the trends in these measures.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. Describe the difference between microeconomics and macroeconomics.

2. Understand what the study of macroeconomics attempts to accomplish, and what it does not try to do.

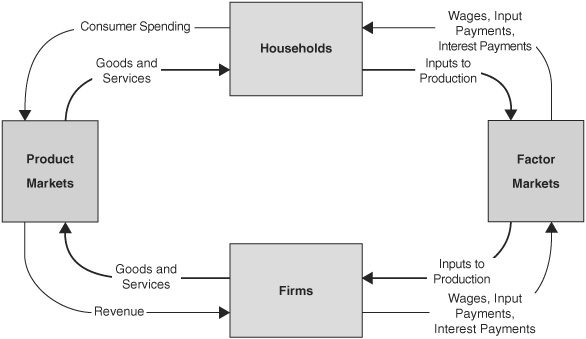

3. Discuss the circular flow diagram.

4. Describe GDP, including the components of GDP and how much of U.S. GDP each component makes up.

5. Explain the two methods of calculating GDP.

6. Discuss the difference between GDP and GNP.

History tells us that crises can lead to major developments and advances in thinking as people try to understand what led to a particular crisis and how to prevent another similar event from happening. Economics is no exception, and modern macroeconomics has its roots in the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Expansions and contractions of business activity were not new at that time, and economists had long studied business cycles, inflation, and growth. However, the scope and scale of the events of the early 1930s were unprecedented. The failure of the “invisible hand” to correct the economic Armageddon of the Great Depression led to a fundamental shift within economics and a schism that divided economics into two distinct fields. Other major events over the past century have further pushed the development of macroeconomics, but we will address those in later chapters.

Before we move on to what macroeconomists do, we need to make the following points about macroeconomics:

• Macroeconomics uses models. Like microeconomics, macroeconomics uses graphs and equations to create a stylized (or simplified) idea of how something is supposed to work.

• Ceteris paribus still holds. There are countless moving parts within an economy. When we are studying the impact of a specific phenomenon on an economy, we still assume that only that phenomenon is changing so that we can focus on what the effect of that thing changing will be.

• The goal of macroeconomics is not to fine-tune the economy. Macroeconomics does not set out to keep business cycles from occurring. To do so would be not only impossible, but perhaps even detrimental to an economy (remember that major advances can come from turning points). The study of macroeconomics is more concerned with understanding how the economy as a whole works, so that policy makers can try to keep major swings in business activity and economic catastrophes, such as the Great Depression, from occurring again.

Imagine that you just got your paycheck. You take that money and use it to pay rent, buy food, and maybe buy a few books at a store. To your landlord, the grocer, and the bookstore owner, the money you have just spent is money that they receive as income. They use that income to pay for the loan to build your apartment, the frozen food manufacturer who supplied the grocer with chicken nuggets, and the clerk to work at the bookstore. In turn, each of those people uses that money to pay some other entity, which then uses that money to pay yet another entity.

This is the basis of our first model of the macroeconomy: the circular flow diagram. This model breaks up the macroeconomy into two main entities, households and firms. Households are buyers of goods, but sellers of the factors of production. Firms are sellers of goods, but buyers of the factors of production. Households take money in exchange for providing labor services, savings, and other resources. They then spend that money for the purchase of goods and services from firms.

Figure 11-1 illustrates this idea. The goods and services being exchanged move clockwise. The payments for the goods and services move counterclockwise. In the figure, the clockwise arrows signify households that sell labor in the factor market; the labor is then used by firms to make goods, which are then sold to the households. In the figure, the counterclockwise arrows show that households receive money for their labor, and they use that money for consumer spending, which becomes revenue for firms.

FIGURE 11-1 • The Circular Flow Diagram

The circular flow diagram illustrates several key concepts:

• This is a snapshot of production within an economy. When macroecono-mists are talking about the goods and services produced by the economy, this is the picture they have in mind.

• One entity’s income is another entity’s spending. Economists would say that income equals expenditures. Basically, income and expenditures are two sides of the same coin.

When you go to the doctor for an annual exam, the doctor generally does more than take a glance at you to determine whether you are “healthy” or “sick.” The doctor will take various measurements to attempt to quantify your health. She might take your temperature, your pulse, your blood pressure, and your weight. Each of these measurements individually provides the doctor with useful information, but taken collectively, they give a more complete idea of your health status. Similarly, we take measures of the macroeconomy to determine how well an economy is doing.

The most important of these measures is the gross domestic product (GDP). This is a measure of the market value of the final goods and services produced within an economy. It gives information on how much economic activity is occurring within the economy. It is also reflects the standard of living within the economy, as our collective income depends on how many goods and services are being produced in the economy. Before we continue to how it is measured, let’s take the definition apart. Gross domestic product is:

• The market value. Gross domestic product is measured in terms of money, the market prices at which goods are sold. This is a necessity because we need some sort of common denominator to add up all of the chicken nuggets, cars, and window-washing services that an economy might produce.

• Of final goods and services. We want our measure of the production within an economy to be as accurate as possible. In particular, we want to avoid overcounting or undercounting. Take, for example, the cars produced in an economy. If we counted the car at its market price, this includes the value of the parts of the car, such as the tires. If we also counted the tires that Ford used when it made the car, we would be claiming that the economy had produced eight tires, when in fact it had produced only four. By counting only final goods, we avoid double-counting.

• Produced within an economy. GDP measures the production of goods within the geographic borders of an economy, regardless of the nationality of the person who owns the factors of production used to make those goods. For instance, if Ford Motor Company operates a plant within Canada, that production is counted as part of Canadian GDP, not U.S. GDP. Similarly, if Volkswagen, a German carmaker, operates a plant in Tennessee, that production is counted in U.S. GDP.

There are two ways to calculate GDP. The simpler way is the expenditures approach. As the name suggests, it involves simply adding up all of the expenditures on final goods and services in an economy. Using this approach, GDP has five components:

• Consumption (C). This is the amount of money that individuals and households spend on final goods and services. In other words, this is the amount of money spent on things like food, rent, jewelry, toys, and pretty much anything else that individuals and households buy. This category is sometimes further broken down into durable goods (goods that are expected to last longer than three years), nondurable goods (goods that are expected to last for less than three years), and services. There is, however, one notable exception in which household purchases, rather than being counted as consumption, are instead counted as investment spending.

• Investment (I). This is the amount of money that is spent on things such as new business equipment, factories, software, and other productive assets. It also includes new houses purchased by households. It can be broken down into residential investment (houses, apartments, and so on), nonresidential investment (office buildings, machinery, and so on), and changes in inventories.

• Government (G). This is the amount of money that is spent by local, state, and federal governments on the purchase of goods and services, such as paying government employees or purchasing missiles. It does not include government spending that merely involves transfers of money, such as social security checks.

• Exports (X). This is the value of goods and services produced in the United States for sale outside the United States. Recall that the purpose of GDP is to capture all production, not just what we consume. Thus, we want to count the goods that we produce and send elsewhere.

• Imports (M). Similarly, we want to take out the goods and services that are produced elsewhere but consumed here. Therefore, we subtract the value of the goods that are produced outside the United States and consumed within the United States. When imports are subtracted from exports, we get the nation’s net exports.

Still Struggling

Still Struggling

You might be confused about why a few things you think you know about the economy aren’t found in that list. Let’s go through some common misperceptions.

• Investment. Why aren’t stocks included in investment? When people use the term investment colloquially, they are usually talking about stocks, bonds, and other financial instruments. That is not what economists mean when they talk about investment. In economics, investment refers generally to the ability to create production or business activity. For instance, when Margaret “invests” in $100 of Google stock, she is purchasing a financial instrument; basically, she is letting Google use that $100 to purchase equipment, inventory, or the like. If we counted that $100 purchase of equipment and the $100 stock purchase, we would be double-counting that $100 and overstating the true production of the economy.

• It’s the change in inventories that matter. You might wonder why purchases of inventory aren’t double-counting. For instance, doesn’t a store with inventory eventually sell that inventory, and wouldn’t that sale be counted in consumption? Well, the answer is, yes, it would, if what we counted wasn’t the change in inventory. For instance, suppose a store purchases $100 worth of T-shirts to put in its stockroom in 2009. That would be counted in the investment category in 2009 because the purchase added $100 of production. If the store sold half of those T-shirts in 2010 for $80, –$50 would be counted in investment in 2010, and $80 would be counted in consumption in 2010 (the net change of +$30 to GDP reflects the value added of the store selling the T-shirts, such as the services of the worker who helps you pick out a shirt).

• Government. Government’s contribution to GDP includes government purchases, but not necessarily all government spending. The category G does not include every time the government spends money; it includes only actual productive activity. For instance, suppose the government spends $1,000 on your grandmother: a $900 social security payment and a $100 payment to her doctor through Medicare spending. The Medicare spending is a purchase of a service—there was actual productive activity involved (a doctor visit). However, the $900 social security payment is what is called a transfer payment—the government is sending your grandmother a check simply because she is retired, not because she is providing the government with a good or service. Moreover, if your grandmother then took that $900 and spent it on food, that would be double-counting.

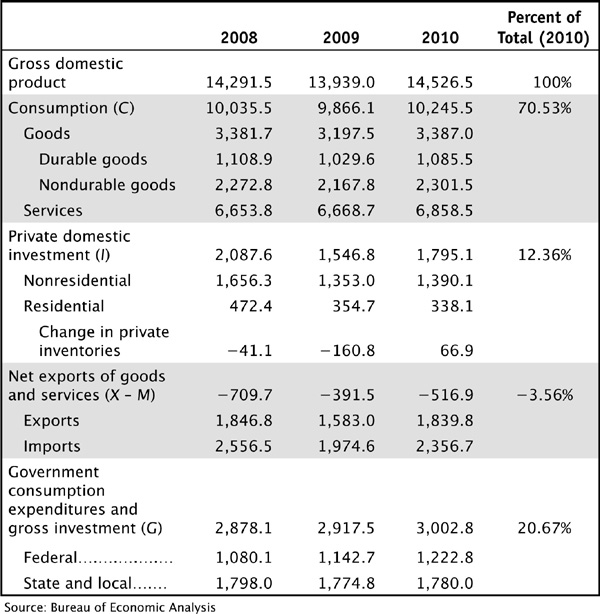

Table 11-1 gives the breakdown of U.S. GDP and its components from 2008 to 2011. From this, we can take away some key points:

TABLE 11-1 U.S. GDP, 2008–2010 (in Billions of Dollars)

• Consumption is the largest component of GDP, and most of that consumption is in the form of services.

• The United States is a net importer, meaning that we typically import more goods and services than we export.

• The greatest variation from year to year is in investment. This is key: the investment category is spending by businesses to produce in the future. If this is going up or down, it reflects how much business activity firms expect to do in the future. It is particularly noteworthy to see the drop in investment in 2009 following the start of the recession in 2008. Even though consumption dropped, it dropped by only about 1.7 percent. Investment fell by 25.9 percent. This is particularly apparent in the change in inventories—it appears that businesses were more interested in getting rid of inventory than in adding to it.

A somewhat less intuitive, but nonetheless important, approach to measuring GDP is the income approach. As its name suggests, this is computed by adding up the various components of national income, called factor incomes. This reflects the fact that these are the incomes that accrue to the various factors of production in the economy. Using this approach, GDP is referred to as national income.

• Wages. This refers to wages, salaries, and benefits earned by labor. It also includes income that comes from social security and unemployment benefits.

• Rents. This includes rental income that households receive from property and capital. It includes rental properties, such as a house that a household may own and rent to someone else, but it also includes royalties from patents and copyrights.

• Interest. This includes interest income that households receive from providing money to corporations, such as returns on stock or bond investments. Interest paid by governments or by households to businesses (such as for mortgages or car loans) is not included in this category.

• Profits. This is the amount of money that firms have left over after paying wages, rent, interest, and other expenses.

Either way you calculate GDP, you should end up with roughly the same number. There is sometimes a slight difference because of the way things are measured and calculated, and slight variation as a result of rounding error, but in practice the differences are negligible. This should not be at all surprising—recall from the circular flow diagram that expenditures simply go in one direction, and income flows in the opposite direction.

Occasionally you may see a different, but similar-looking, measure called gross national product (GNP) reported. GNP is the measure of all final goods and services that are produced by the productive assets of a country, whereas GDP is the measure of all final goods and services that are produced within the geographic borders of a country, regardless of who owns the resources. For example, consider Toyota Motor Manufacturing, Kentucky (TMMK), an automotive factory in Georgetown, Kentucky. The firm TMMK is located within the geographic borders of the United States, and so its production would be counted in various parts of U.S. GDP. However, TMMK is wholly owned by the Toyota Motor Company, which is headquartered in Japan. Therefore TMMK’s production would be counted not in U.S. GNP, but in Japan’s GNP.

The intuition behind GDP and GNP is similar, but the uses and interpretations differ slightly. Gross domestic product is a good measure of how the local economy of a country is doing, whereas GNP gives a better picture of how well off the nationals of a country are economically. For instance, if a very large share of a country’s resources is foreign-owned, the proceeds from that production are likely to go elsewhere. Certain subfields of economics, such as development economics, use this measure because they are ultimately more concerned with the well-being of the individuals within a country.

This chapter described the difference between microeconomics and macroeconomics, and why we distinguish between the two. It introduced one of the key measures of the health of a macroeconomy, GDP, and how it is calculated. Gross domestic product was broken down into its five components, and we explained some common misconceptions concerning what production is and is not included in the nation’s official GDP calculations. Finally, we introduced the concept of GNP, and why this slightly different measure is sometimes used. The key idea in this chapter is that a country’s well-being depends on its ability to produce goods and services. Of course, in order to produce those goods and services, you need to hire workers. In the next chapter, we extend our discussion of trying to measure the health of an economy by looking at the employment picture, specifically, how and why we measure employment and unemployment.

Is each of the following statements true or false? Explain.

1. Microeconomics and macroeconomics are different names for the same study of economies.

2. In the United States, government spending makes up the greatest percentage of GDP.

3. Investment spending is the most volatile portion of GDP.

4. Gross national product is an indication of what is produced within a country’s borders.

5. Gross domestic product counts all goods and services that are produced within a country.

Give a short answer to the following questions.

6. A store purchases grogs to put in its storeroom in 2009 for a total of $200. In 2010, the store sells those same grogs for a total of $300. Explain how each of these appears in the calculation of GDP.

Use the following information to answer questions 7 through 10.

Within the nation of Maxistan in 2010, all of the sales of goods and services can be described as follows: durable goods of $500, new homes of $1,000, used homes of $200, inventories of $300, nondurable goods of $900, and government purchases of $400. In addition, Maxistan imported $150 worth of goods and exported $280 worth of goods.

7. Describe which category of GDP each item sold in Maxistan would fall into, using the expenditures approach to calculating GDP.

8. Calculate the GDP of Maxistan.

9. Which items sold in Maxistan aren’t counted in GDP? Why aren’t they counted?

10. Is Maxistan a net exporter or a net importer? Explain.