+ savings accounts + small time deposits (that is, certificates of deposit that are under $100,000) + money market deposits + money market mutual funds.

+ savings accounts + small time deposits (that is, certificates of deposit that are under $100,000) + money market deposits + money market mutual funds.Money surrounds us, we use it daily, and it affects our lives in both seen and unseen ways. However, it is certainly the least understood aspect of the economy. In this chapter, we discuss money—what it is, why we want it, and how it influences the macroeconomy. We introduce the money market, which affects the interest rate and in turn the investment that we discussed in previous chapters. We conclude by talking about the role of a central bank in an economy.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. Describe the functions and types of money.

2. Calculate the money multiplier and describe how banks create money.

3. Describe and model the money market, including how interest rates are determined and how the money supply is increased and decreased.

4. Relate the money supply to inflation.

5. Describe the role of the central bank and the structure of the central bank in the United States.

When most people refer to money, such as how much money they have in their wallet or their bank account, they are really talking about wealth, the ability to convert some store of value into consumption. To an economist, however, money is defined by what it does. Money is any kind of asset that fulfills the functions of money. The three functions of money are:

• A unit of account. To be considered money, an asset must be able to serve as a standard unit of measurement of the value or prices of goods. That is, we must be able to say that a television is worth a certain amount of dollars, or a certain amount of pieces of metal.

• A store of value. To be considered money, an asset must be able to reasonably maintain that unit of value. Ice, for example, would do very poorly at this function, as it would be extremely difficult for it to remain ice. Metal or paper or even salt, however, could easily maintain its value.

• A unit of exchange. To be considered money, an asset must be accepted in exchange for goods or services. Note that this is the basis of why we want it to store value.

Anything that can perform all three of these functions can serve as money, and many different things have served as money since humans began using money several thousand years ago. In fact, everything from giant rocks, to seashells, to salt has been used as money (in fact, the word salary is derived from the Latin word for salt, which was used to pay Roman soldiers).

The items that are used for money fall into two categories, commodity money and fiat money. Commodity money, such as gold or salt, is something used as a medium of exchange that has use value of its own. Fiat money, on the other hand, is money with no intrinsic or commodity value (or whose intrinsic value is minuscule compared to its face value). The paper and coin money that are in circulation today are fiat money.

A great example of what money is and how it works is illustrated in a 1945 article by R. A. Radford in the journal Economica. Radford was an economist who was captured during World War II and spent time in a German prisoner-of-war camp. There was an official currency circulating in the camp, the Reichsmark, but it was not used for trade between prisoners; it could be used only to purchase items from the canteen (which frequently meant that it had no exchange value at all, as relatively little was available at the canteen). However, each of the prisoners in this camp had a regular allotment of goods in the form of his rations and Red Cross packets that contained items like milk, chocolate, and cigarettes, and occasionally some prisoners received private packages of things like clothing and toiletries. At first, trade was carried out through barter, but this was very inefficient (if you wanted to trade chocolate for bread, you had to find someone who was willing to trade bread for chocolate). Nonsmokers would trade their cigarettes for something that was of value to them. Soon, however, the cigarettes arose as a single unit of account. Someone might walk through the camp offering to sell “cheese for seven [cigarettes].” People were willing to accept cigarettes in trade because they knew that they could, in turn, use cigarettes to acquire goods that they wanted.

An interesting aspect of this cigarette money system is that it soon experienced a problem that all commodity money faces: Gresham’s law. The gist of Gresham’s law is that bad money will chase out good. The cigarettes worked well as money because they were an easily recognizable unit of exchange, not because they had intrinsic value. In fact, people would frequently pinch tobacco out of the cigarettes and hand-roll cigarettes to smoke. This took the part of the money with commodity value (the tobacco) out of the money and left the shells of cigarettes (the bad money) to be traded.

Many things can be money, but above all else, what makes something money is the belief that it can serve the functions of money. If we suddenly were in doubt that the paycheck we received from an employer could be converted into goods and services, we would be unwilling to exchange our labor for it. In a sense, money is money only as long as we believe it is money.

This raises a question: where does money come from? Before we describe how money is created, let’s be specific about what we count as money in the United States. In the United States, the stock of money on hand, or the money supply, is tracked by the Federal Reserve, the central bank of the United States. The Federal Reserve breaks the money supply into two categories according to its liquidity, meaning the relative ease with which an asset can be converted into cash. The second category is less liquid than the first:

• M1 = cash (currency) outside of banks + coins + checking deposits + traveler’s checks.

M1 is the most liquid category. Cash can easily be converted into itself; checking accounts have relatively few restrictions on taking money out; traveler’s checks are widely accepted, and when you make a purchase with a traveler’s check, you receive change in cash.

•  + savings accounts + small time deposits (that is, certificates of deposit that are under $100,000) + money market deposits + money market mutual funds.

+ savings accounts + small time deposits (that is, certificates of deposit that are under $100,000) + money market deposits + money market mutual funds.

The instruments in the category M2 are slightly less liquid than those in M1. Many of these types of accounts have more restrictions on them, such as savings accounts that have a 10-day hold before you can withdraw money deposited. M2 is sometimes referred to as near money, because although it is not directly convertible as a medium of exchange, it can be converted into money fairly easily. According to the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), in mid-August 2011, M1 was $2,085.8 billion (or about $2.085 trillion) and M2 was $9,521.8 billion.

If you were under the impression that the institution that creates money in the United States is the Treasury Department, the agency that prints currency, then you would be wrong. Only about half of the money supply is made up of currency. Banks create money when they issue loans. The basis of how banks create money is a banking practice known as fractional reserves. A bank does not keep all of the money that is deposited on hand; instead, it keeps a fraction of what is deposited. This fraction of reserves, called a reserve ratio, is used to meet the day-to-day cash needs of depositors. The remainder is used to make loans.

To understand how fractional reserve banking works, and how it leads to the creation of money, let’s walk through an example using a T account. A T account is a way of keeping track of a bank’s liabilities, that is, its obligations to pay out money, and its assets, that is, the things it holds that are of value. For a bank, any deposit that an individual makes is a liability, because that person may withdraw it at any time. On the other hand, a loan is something that has value, as it is income that the bank will be taking in (in fact, loans are sometimes even sold to another financial institution). A T account has two sides, with assets on one side and liabilities on the other side (it is called a T account because that is what it looks like).

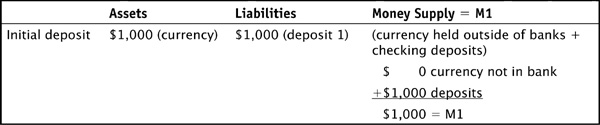

Let’s start with an economy with $1,000 in currency and no banks. Then City National Bank opens. Suppose that an initial deposit of $1,000 is made, and the bank is required to keep at least 20 percent of deposits on hand (known as a reserve requirement). We note how this affects the bank’s T account, and the money supply, in Table 15-1. The $1,000 deposit is a liability for the bank, but the $1,000 that the bank now has in its vault is an asset.

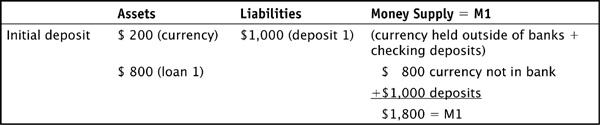

The bank is required to keep only 20 percent of that deposit on hand, so it really needs to have only $200 in its vault. In essence, it has an extra $800 on hand that it can lend and earn interest on. When the bank lends money, it appears in the T-account as shown in Table 15-2.

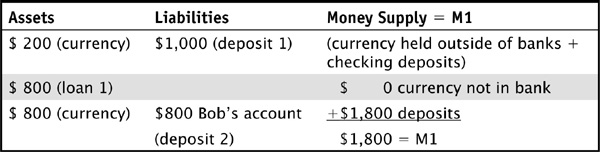

There are two things to note about this action. First, it is important that the bank remain solvent, that is, its liabilities must not exceed its assets. Second, the action of making the loan increased the money supply. When we say that banks create money, this is exactly what we are talking about. Interestingly, this process doesn’t end here. Suppose the borrower uses that $800 loan to purchase equipment from Bob’s Tractor Supply. Bob then deposits that money in the only bank in town, as shown in Table 15-3.

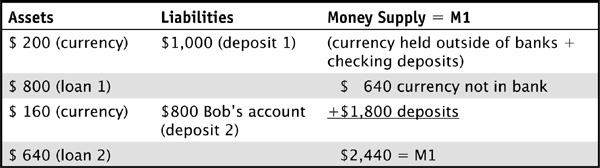

Once again, the bank is holding more cash than it is required to. It must keep 20 percent of the initial deposit and 20 percent of Bob’s deposit (or $160), so it needs only $360 in its vault. This means that it has an extra $640 that it can lend. If it does this, its T-account changes, as shown in Table 15-4.

Again, note that this loan expanded the money supply. This process can be repeated over and over again, leading to multiple expansions of deposits. We could continue forward, redepositing $640 and keeping $128 on hand, then lending $512, and so on to figure out what the money supply will be. However, it turns out that there is a mathematical shortcut. We can find the money multiplier to figure out what the amount of the money supply will be if we assume that banks keep only the required reserves on hand (that is, they do not keep excess reserves), and that all loans are redeposited (that is, someone doesn’t take out a loan and do something like stick the money under her mattress). The money multiplier (MM) is:

In our case, the base money is the initial amount of currency in the economy, $1,000. With a reserve requirement of 20 percent, this becomes

To find out what the final impact of the multiple expansion of deposits will be, we multiply the money multiplier by our initial stock of money. In this case,  , so we will end up with a money supply of $5,000.

, so we will end up with a money supply of $5,000.

Still Struggling

Still Struggling

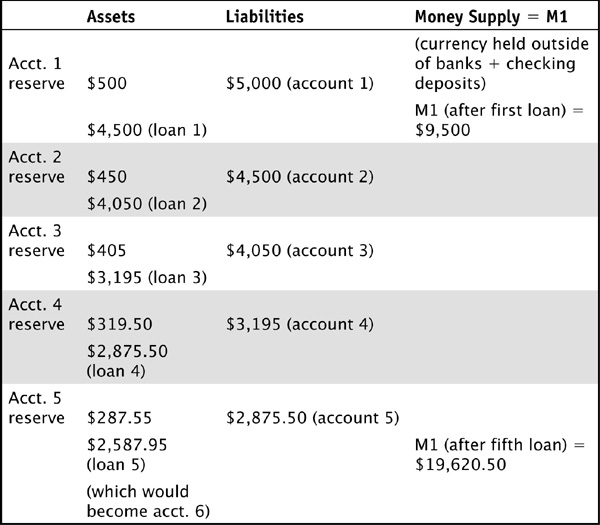

Whenever you are dealing with a mathematical calculation, it’s useful to work through more than one example. In the case of the multiple expansion of the money supply, this is even more critical to help you “wrap your head around” something that seems pretty far-fetched. To help you convince yourself that this is actually how the money supply is determined, do the following as you are walking through the steps: (1) keep track of what the money supply is at each step, and (2) remind yourself that money in the vault (reserves) doesn’t count as part of the money supply because it can’t be used to purchase goods and services. Money in circulation does count, as does what is in a bank account, because those monies can be used to buy goods and services.

Take another example of an economy that starts with an injection of $5,000 into its economy, has a reserve requirement of 10 percent, and requires that banks fully lend (that is, they do not keep excess reserves) and that all loans are redeposited. The first five iterations of the multiple expansion are in Table 15-5. Try doing them on your own to test yourself.

So how is the money supply in an economy actually determined? This process indicates that there are two pieces of the economy that determine what the money supply will be. The first and most important piece is the Federal Reserve System, which determines the amount of base money in the economy and sets reserve requirements for banks. The second piece is the banks themselves, which decide whether or not to keep reserves above the required amount and whether or not to make loans. The Federal Reserve System is the central bank in the United States. A central bank is an institution that oversees and regulates the banking system in an economy and controls the monetary base.

The Federal Reserve (or the Fed for short) was created by an act of Congress in 1913, largely in response to many banking panics that had occurred in the late 1800s and early 1900s. It consists of two parts, the Board of Governors and 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks. The Board of Governors oversees the entire system from its location in Washington, DC, and has seven members, including a chair. The governors are appointed by the president with the approval of the Senate for 14-year terms, except for the chair, who is appointed for a four-year term. The 12 Federal Reserve Banks each serve a region of the country called a Federal Reserve District. For instance, the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas serves all of Texas, southern New Mexico, and northern Louisiana. Each of the 12 banks is operated by a board of directors that is made up of local banking and business leaders. The president of each bank is appointed by its board and approved by the Board of Governors.

The Fed has an unusual place in the economy, as it is neither a government agency nor a truly private institution. The Fed is independent of the government in the sense that its decisions do not have to be approved by any of the three branches of government (judicial, legislative, or executive). Another interesting aspect of the Fed is that its operations expenses are paid for out of the fees charged for the services that the Fed performs, and any profits are turned over to the Treasury.

The Federal Reserve System has two main objectives. First of all, it is charged with maintaining the operation of a healthy banking system. It does this by serving as a clearinghouse for checks, auditing banks within each district, setting the reserve requirement for banks, and serving as a lender of last resort for banks. For instance, if a bank finds itself short of funds to meet its reserve requirements, it can borrow from other banks to cover this shortfall or, if no other banks are willing to lend to it, from the Fed. The second objective is to maintain the money supply and carry out monetary policy, which is the attempt to manage macroeconomic performance through the control of the money supply.

At least eight times a year, the Federal Reserve announces what the federal funds rate will be. The federal funds rate is the rate that banks charge each other for short-term, even overnight, loans. This is usually announced in news outlets with headlines such as “the Federal Reserve moved today to lower interest rates to . . .” or “the Federal Reserve raised interest rates.” The truth is that the Fed doesn’t, as some people mistakenly believe, set interest rates. Rather, a committee within the Fed called the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) uses the money market to achieve a target rate of interest. The committee’s name implies that it does this on a market, much like the ones we have seen in our chapters on microeconomics. This is, in fact, exactly what it does.

The supply side of the money market is the money supply we have developed in this chapter. Recall that the Federal Reserve decides on what the amount of money in the economy should be. At any point in time, the amount of money in the money supply is a fixed amount. Therefore, the money supply curve is vertical at a single point, as shown in Figure 15-1. The process by which the money supply changes is somewhat complicated, and we address this in the next chapter.

FIGURE 15-1 • The Money Market

The other side of the money market is the money demand curve. The money demand curve illustrates how much money people are willing to hold at various interest rates. At first it might not be intuitive that people would decide on how much money to have based on the interest rate. The key to this is to remember that there is an opportunity cost of holding money—the interest rate. Consider the decision on whether to take money out of savings and have it on hand to spend, either in your pocket or in a non-interest-bearing checking account. The higher the interest rate on your savings account, the more interest income you lose by keeping that money in your pocket.

The demand for money will depend on a number of factors, and changes in these can shift the demand curve for money in (decrease the demand for money) or out (increase the demand for money). First of all, changes in the aggregate price level will increase the demand for money. If everything you purchase costs more, you need to keep more money on hand to maintain the same amount of consumption, regardless of the interest rate you might otherwise be earning. Second, if GDP changes, so does the demand for money. Intuitively, if people are purchasing more goods and services, they will need more dollars with which to do that, and the demand for money will increase. Finally, technology and habits play a role in the demand for money. For instance, the demand for money usually increases during the winter months, as people tend to buy more for holiday celebrations. Also, technological changes such as the introduction of ATM machines have made it easier to get money as needed and made it less necessary for people to keep larger amounts of money on hand.

According to liquidity preference theory, the interest rate is determined by the interaction of the supply and demand for money, as illustrated in Figure 15-1. In other words, the interest rate will adjust to bring the amount of money that people want in line with the amount of money that actually exists. Consider what would happen if the current interest rate was higher than the equilibrium interest rate. In this case, people would not be as willing to hold money because they would be able to earn a higher interest rate by placing that money into something like a CD (remember that a CD is a near-money asset). Banks that were selling such assets would find that they could sell them at a lower price and still find willing buyers. This would place downward pressure on the interest rate until it reaches equilibrium. Conversely, if the going interest rate were lower than the equilibrium rate, people would be willing to hold more money than actually exists and would be less willing to hold on to near-money assets. Gradually banks would have to offer higher and higher interest rates on the near-money assets in order to get people willing to hold on to less wealth in the form of cash.

In this chapter, we discussed the purpose of money in the economy. We began with a discussion of the fact that an asset is considered money because of the functions that it performs, rather than by being a particular kind of paper or coin. We continued by introducing the concept of a money supply, how the practice of fractional reserve banking creates money, and what role a central bank such as the Federal Reserve System plays in the creation of the money supply. Finally, the role of money in determining interest rates through the money market was introduced. The fact that a central bank can manipulate the money supply, thus shifting the money supply curve and changing the interest rate, has an important implication. The interest rate influences household spending decisions and business investment decisions. Changes in the interest rate, then, can be used to change our macroeconomic variables such as GDP. We turn our attention to how and why this might be done in the next chapter.

Is each of the following statements true or false? Explain.

1. Anything that cannot perform all three functions of money will not be able to be used as money.

2. Something must have intrinsic value in order to be used as money.

3. Something is money because we believe it to be money.

4. M2 is sometimes called “near money.”

5. If the reserve requirement is 5 percent, then an injection of $1,000 will definitely result in an increase of $20,000 in the money supply.

6. The Federal Reserve sets interest rates.

7. The Federal Reserve was created in response to the Great Depression.

8. According to the theory of liquidity preference, the Federal Reserve should set an interest rate that clears the money market.

9. If all of a sudden debit cards were made illegal, the demand for money would probably decrease.

10. If the Federal Reserve increased the money supply, the interest rate would increase.