The healthcare industry has recently garnered a great deal of attention during the debates leading up to the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (PPACA 2010, but sometimes also just called the Affordable Care Act). However, much of the debate and public discourse on this act indicates that, by and large, the public does not understand how this industry works. In this chapter, we examine the markets for health and healthcare. We start by discussing why healthcare in the United States is financed differently from the way it is financed in any other country. We continue by explaining why we have to reexamine our assumptions about markets and the consequences of healthcare markets being fundamentally different, and the difficulties this presents for a healthcare financing system. Finally, we discuss the demand for health insurance and the challenges of setting health insurance premiums.

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. Briefly describe the historical development of the U.S. healthcare financing system.

2. Describe why healthcare is fundamentally different from other goods and how increasing competition may have unintended consequences in healthcare markets.

3. Define asymmetric information and moral hazard, and describe how these affect healthcare markets.

4. Explain the premium death spiral and the benefits and drawbacks of insurance mandates.

The largest industry in the United States in terms of share of GDP is government (including federal, state, and local governments). Many people would be surprised to learn that the second-largest industry in the United States is not the automotive industry or steel, but healthcare. In fact, according to most estimates, healthcare makes up around 17 percent of GDP and is growing much faster than any other industry.

Given the size of this industry, it might be also be surprising that the field of health economics is somewhat new. The academic journal of health economics research, the Journal of Health Economics, did not begin publishing until 1982. In fact, a paper that is considered to be the seminal (beginning) work in health economics, “Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care,” by a Nobel Prize–winning economist named Kenneth Arrow, was not published until 1963. Why did healthcare as an industry suddenly start to attract attention? To answer this question, we have to start with a brief history of how healthcare financing, or the way healthcare is paid for, has changed in the United States over the past 100 years. As with so much else in economics, the changes began around the time of the Great Depression.

Prior to 1900, healthcare was still fairly primitive. Germ theory was relatively new, and the introduction of anesthesia during the Victorian era had just made surgery a less barbaric option. In the early 1900s, there was a radical alteration in medical education that changed physicians from a hodgepodge group of variously qualified tradesmen into a profession with a set of standards for education, training, and ethics. However, the technology available was still fairly simple—x-rays were not used therapeutically until 1908, and even though it was discovered in 1928, penicillin wasn’t in widespread use until the 1940s.

When it came to financing, this was also fairly simple. The health insurance that we are familiar with today simply did not exist. While casualty insurance, or insurance to cover a defined loss, had been in existence since antiquity, commercial insurers were not interested in insuring healthcare because of the difficulty in defining a loss (in other words, how can you really insure “health”?). If you needed healthcare, either you paid for it out of your own pocket, you received charity care, or you simply went without it.

Even though most hospitals were not-for-profit entities, their revenues were severely affected by the Great Depression. Take, for example, Baylor University Hospital (BUH) in Dallas, Texas. In 1929, hospital receipts (that is, money received from patients) were $236 per patient, but in 1930, those receipts were a mere $56 per patient. Meanwhile, charity care had increased 400 percent. As bad as this sounds, BUH was doing better than many other hospitals at the time, and many closed. This was obviously not sustainable, however, and a BUH hospital administrator came up with a plan. The hospital approached the Dallas Independent School District and offered it a hospital plan—if every single teacher in the system enrolled and paid 50 cents per month, each teacher would be guaranteed to have up to 21 days of hospital care covered (not physician services, however—physician charges are different from hospital charges, and physicians were largely opposed to any kind of insurance system). The steady stream of income from a group, or pool, of relatively healthy and young people provided guaranteed revenue for the hospital, and individuals in the plan had the peace of mind that it provided at a relatively low cost.

Similar hospital plans became more common, and hospitals began asking their trade association, the American Hospital Association (AHA), to develop a systematic way to implement them. In 1936, the AHA developed the AHA Service Plan. In 1946, the committee overseeing this plan became the AHA Blue Cross Commission. As physicians began to accept the idea of such insurance plans, a partner commission, Blue Shield, was formed, giving rise to the now familiar Blue Cross/Blue Shield, a nonprofit health insurance company.

The real spread of health insurance, however, occurred during the next great crisis in the United States—World War II. During World War II, price controls were implemented as a way to control the inflation that often occurs during wars (when an economy is trying to produce beyond its full-employment level of output). Firms faced labor shortages, but they could not use higher wages to attract more workers because of the wage controls that were in place to prevent the type of inflation that is common during wars. However, a ruling by the Internal Revenue Service allowed benefits such as health insurance to not be subject to price controls, and employers began offering health insurance plans as part of their benefits packages.

Not long after this, the Internal Revenue Service decision meant that such benefits were also not subject to income tax. This has an important implication from the employee’s point of view—more benefits become more attractive than more salary. Consider a worker who has a marginal tax rate of 20 percent. If the worker is offered $1 more in salary, she takes home 80 cents. However, if the worker is offered $1 in health insurance, she gets the full $1 worth of insurance. These two events lead to a peculiar feature of the U.S. health financing system: employer-based health insurance.

The next major change in healthcare financing in the United States came in the 1960s. Titles XVIII and XIX were added to the Social Security Act in 1965, creating the social insurance programs Medicare and Medicaid. Social insurance is a type of insurance in which a government becomes the payer, as opposed to private insurance, where a private entity such as an insurance firm pays for healthcare. Medicare covers the elderly (those over age 65) and was modeled after the Blue Cross/Blue Shield system. Medicaid covers certain low-income individuals and is a joint federal and state program.

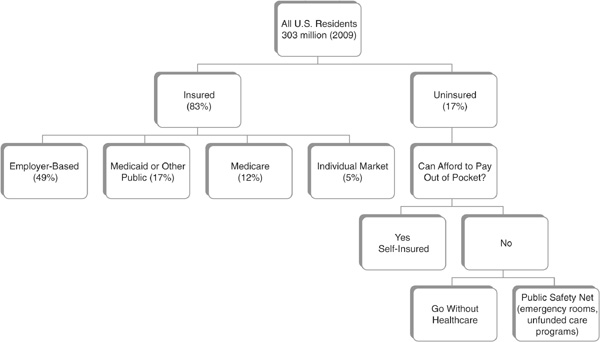

The end result is that the United States has a mixed system. Figure 19-1 breaks down the percentage of individuals in the United States that fall into different healthcare financing categories, using data from the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that tracks healthcare issues and statistics. We have private employer-based insurance, which covers about half of all individuals (most individuals who have any form of health insurance are covered through their employer), and a very small market for individual insurance. For those without health insurance, the final safety net for healthcare financing is receiving healthcare through emergency rooms (which cannot legally turn individuals away) or government-funded programs that reimburse hospitals for some of the amount of unfunded care they provide.

FIGURE 19-1 • Breakdown of U.S. Healthcare Coverage by Financing Categories

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

Healthcare is a good that is fundamentally different from other goods. To see why, let’s review some of the assumptions of a competitive market and see how well they apply to healthcare.

1. Free entry and exit of firms. Sellers of healthcare, such as hospitals and physicians, do not have free entry and exit. We require licensing and certification to ensure quality.

2. Perfect information and no uncertainty. Healthcare markets are fraught with uncertainty. We do not know if we will need healthcare tomorrow or next year. We don’t always know that a particular treatment will work. Our physicians have a better idea than we do, but this means that there is asymmetry between what the buyer (the patient) knows and what the seller (the doctor or hospital) knows. Moreover, because of health insurance, we frequently don’t even know what a particular treatment costs.

3. A homogeneous product. Physicians and other healthcare professionals aren’t alike. All else equal, we would prefer higher quality to lower quality. However, quality can be expensive. If we are insulated from the true price of a good—for instance, if it is covered by insurance—we may look for the best quality possible. This means that firms are competing on the basis of quality rather than price.

4. Buyers and sellers are price takers. Sellers negotiate prices with insurance companies, and buyers are frequently unaware of prices.

5. Utility maximization/profit maximization. Individual physicians have more than just a profit motive—while they are certainly interested in creating an income, they also have an altruistic motive. In the United States, the dominant business form of hospitals is not-for-profit, which means that profit maximization must not be their goal.

6. No externalities. Vaccines, as we mentioned in the previous chapter, are just one example of the positive externalities that healthcare exhibits.

7. Price rationing. Recall from the discussion on externalities that price serves an important function—it brings supply and demand into equilibrium. If there is no price, or if price is effectively hidden, as it is in any system with a third-party payer (a payer that is not the patient or provider), then price has no ability to perform its rationing function.

The net effect is that the market for healthcare does not function in accordance with our traditional competitive market assumptions. In particular, healthcare that is financed through a third-party-payer system may lead to a situation in which increased competition actually drives up costs. Consider an individual who is covered by insurance, be it social insurance or private insurance, and who is looking for a hospital in which to have a baby. If she is covered by insurance, she is not concerned with costs. She is, however, concerned with whether or not she gets a private room, whether or not there will be an assigned nurse for her, how nice the meals are, or even whether there is a “gift box” for the new parents. All of these things would drive up the costs. The more hospitals there are in the market, the more each individual hospital would have to do to “one-up” another hospital in order to attract patients. This can lead to a medical arms race, a term that describes how quality and cost continue to escalate as hospitals compete with one another.

As in the case of externalities, the key here to bringing the costs back down is to bring some sort of rationing back to the system, whether price rationing or some other form. This might be done by reintroducing some sort of price sensitivity. Insurance companies accomplish this with the use of cost sharing tools such as copayments and deductibles. For instance, if a family has to consider that it will pay 10 percent of a hospital bill, known as coinsurance, it will be more sensitive to price and limit its consumption of high-quality (in other words, expensive) services. This can also be done by creating provider networks. When insurance companies limit individuals to certain providers, they have negotiated lower payments to these providers in exchange for guaranteeing a certain volume of patients. Finally, private and public insurers alike can limit what services they will pay for. Each of these is a form of rationing that is implemented to replace the rationing function of price.

The primary healthcare financing mechanism for most individuals is private insurance. In order to understand the market for healthcare, one needs to understand how the supply and demand for health insurance are determined. For this, we will move away from a supply and demand diagram briefly and look at each analytically.

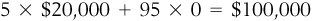

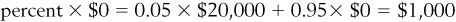

Let’s consider a group, or pool, of 100 people. In any given year, each of these people has a 5 percent risk of having a health issue that entails a cost of $20,000. To find the amount that the insurance company expects it will have to pay in a given year, we need to find the expected value of the loss that the insurance company will incur. If 5 percent of the people in the pool will lose $20,000 each, with a pool of 100 people, the insurance company will expect to pay  . If the insurance company divides this up among all the people in the pool, we get what is called an actuarially fair premium—in other words, a premium that accurately reflects the probability of a loss. Here, the actuarially fair premium would be

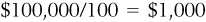

. If the insurance company divides this up among all the people in the pool, we get what is called an actuarially fair premium—in other words, a premium that accurately reflects the probability of a loss. Here, the actuarially fair premium would be  per person. However, administering the plan is not costless for the insurance company—it must hire workers to make sure the providers get paid, rent offices, incur other administrative costs, and possibly even make profit—the company passes these costs along to the buyers of insurance in the form of a loading fee. Let’s suppose that a particular insurance company charges a loading fee of $200. Therefore, the amount of the insurance premium that the insurance company charges would be $1,200.

per person. However, administering the plan is not costless for the insurance company—it must hire workers to make sure the providers get paid, rent offices, incur other administrative costs, and possibly even make profit—the company passes these costs along to the buyers of insurance in the form of a loading fee. Let’s suppose that a particular insurance company charges a loading fee of $200. Therefore, the amount of the insurance premium that the insurance company charges would be $1,200.

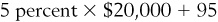

Now let’s consider this from the individual’s side. The individual knows that she has a 5 percent risk of losing $20,000 and a 95 percent risk of losing nothing. To the individual, her expected loss is a probability weight of these two potentials:

. This means that, on average, the individual can expect to lose $1,000 and so would be willing to pay at least this much. However, the possibility of losing much more is daunting to anyone who is risk averse. Because of this, a person would be willing to pay an amount greater than the actuarially fair premium just to avoid that possibility. Suppose that an individual was willing to pay a risk premium of $200 on top of any actuarially fair premium, meaning that the individual was willing to pay a total premium of $1,200.

. This means that, on average, the individual can expect to lose $1,000 and so would be willing to pay at least this much. However, the possibility of losing much more is daunting to anyone who is risk averse. Because of this, a person would be willing to pay an amount greater than the actuarially fair premium just to avoid that possibility. Suppose that an individual was willing to pay a risk premium of $200 on top of any actuarially fair premium, meaning that the individual was willing to pay a total premium of $1,200.

At first this seems perfect—the price that buyers are willing to pay is exactly the price at which sellers are willing to sell. However, there are two characteristics of healthcare markets that will alter this. The first is moral hazard. The underlying idea of moral hazard is that, once they are insulated from the financial impact, people will alter their behavior. For instance, they will consume more healthcare than they otherwise would, or they will engage in riskier behavior. Our family looking for a hospital would choose services that it otherwise would not, or one of our 100 people might do things that would make his risk of loss increase from 5 percent.

To understand the other issue, adverse selection, let’s consider what would happen to our insurance market if one more person entered this pool. This person, however, has a 100 percent risk of losing $20,000, but the insurance company cannot distinguish him from anyone else. Now, the insurance company has a pool of 101 people and an expected loss of $120,000, yielding an actuarially fair premium of $1,188 and a total premium of $1,388. This is more than anyone other than the person who has a guaranteed loss is willing to pay, and people elect not to buy insurance.

This is a very simple illustration of a problem called the premium death spiral. If premiums increase, people with lower expected losses will drop out of an insurance pool when the premiums increase beyond the amount that they are willing to pay. As healthier people drop out of the pool, the expected loss goes up, and insurance companies will be forced to raise the premium again. Eventually, the only people left in the pool will be those who have guaranteed losses. In other words, it leads to a complete failure of insurance. This is why it is called adverse selection. When insurance companies charge more, they are less likely to attract the people they want most—the healthy—because those people are willing to pay less.

Still Struggling

Still Struggling

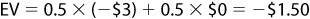

The idea of expected value can be tricky. To understand what an expected value of loss is, consider a gamble that forces you to flip a coin 100 times, and any time tails comes up, you must pay $3. You know that, on average, heads will come up as often as tails, so 50 percent of the time you will pay $0 and 50 percent of the time you will pay $3. This means that you should expect to lose about $150 from having to play this gamble.

You could then extend that to having to play the game just once. You know you will have a 50 percent chance of losing $3 and a 50 percent chance of losing nothing. Mathematically, then:

The goal of a healthcare system is to make healthcare affordable and high-quality, and to have wide access to it. Unfortunately, the problems of moral hazard and adverse selection make this trinity difficult to achieve. Healthcare reform has tried to tackle these issues in a variety of ways and with varying success.

If the focus of a system is on cost alone, in an attempt to make healthcare more affordable, then this can be accomplished by limiting access to care or reducing quality. Consider the issue of access. From an equity point of view, it would be ideal if anyone who needed healthcare could obtain it. There are various financing systems that could accomplish this. For instance, there could be a private, multipayer system in which people who could not easily get insurance were assisted in obtaining it. The PPACA provides for subsidies for those who cannot afford private health insurance and the creation of systems to match up insurance with people who cannot obtain it through their employer. Other countries, such as Canada, have used a single-payer system, in which there is essentially a single insurance company (the government) that provides health insurance.

Unfortunately, universal coverage of any kind would worsen the problem of moral hazard. Universal coverage describes the situation in which every single person in a healthcare system is covered by insurance, and if everyone has coverage, then everyone has insulation against cost. Because of this, the cost of healthcare could increase, making it less affordable. Moreover, if people have the option of opting out of a system, they might do so if the cost exceeded their perceived risk. On the other hand, universal coverage may lead to lower costs if it encourages prevention of disease. Without more information about the problems a healthcare system is facing, it is not possible to say which is likely to have a greater effect on overall spending.

The problem of people choosing to opt out of a system (and still having a safety net) is one of the reasons that the PPACA required an insurance mandate, meaning that people are required to have health insurance: to prevent the problem of adverse selection. Insurance mandates are controversial, at least in the United States. Many people object to the idea of being required to purchase something that they may never need. However, the problem arises when someone does need it. In essence, healthcare in the United States could be considered a common resource. It is rival in the sense that healthcare resources are finite and need to be used effectively. It is also nonexcludable, as our current system has safety nets such as emergency rooms to enable people to get care regardless of their insurance coverage or their ability to pay. Because of this nonexcludability, when people are uninsured, whether by choice or by constraint, there is an opportunity to free-ride off the payments made by private insurance companies and government resources. In fact, the lack of an insurance mandate makes the U.S. healthcare system unique among those of other industrialized nations, as other countries with a variety of different systems all require individuals to be covered by either public or private insurance.

Healthcare is a good that is fundamentally different from other goods because almost none of the assumptions of a competitive market hold for healthcare. Issues such as asymmetric information, moral hazard, and adverse selection make the functioning of a private health insurance system somewhat problematic and may lead to market failures. Given that this is the primary financing system for healthcare in the United States, recent healthcare reform could actually be considered health insurance reform. Whether or not this reform effort will achieve the three goals of a healthcare system remains to be seen, and much research on the issue is likely to be done in the near future. In our final chapter, we turn our attention to this research process, and how economists develop and test ideas and disseminate information to arrive at the ideas and conclusions that we discuss in this book.

Is each of the following statements true or false? Explain.

1. Healthcare is the second-largest industry in the United States.

2. Given the U.S. tax system, an additional $1 worth of health insurance is worth less than an additional $1 in income.

3. The largest number of Americans get health insurance through individual markets.

4. The U.S. healthcare system could be considered a private system.

5. It would be appropriate to use a traditional competitive market model to analyze healthcare markets.

6. If all healthcare were self-financed, moral hazard would not be an issue.

7. Insurance mandates would solve the problem of moral hazard, but would worsen adverse selection.

8. A risk premium reflects the potential risk of a loss.

9. Healthcare is not rationed in the United States.

10. Coinsurance can mitigate the problem of moral hazard.