But when all the criteria of civilization have been considered—language and communication, technology, art, architecture, political, economic and social organization and ideological developments—it can be said that the available evidence, however fragmentary or circumstantial, does suggest that the Akan sometime between A.D. 1000 and 1700 progressed rapidly from the level of peasant agricultural communities to the level of urban societies and principalities, culminating in the establishment of an indigenous civilization.

—James Anquandah, Rediscovering Ghana’s Past (1982)

Needed for more than brute labor on New World plantations, African workers carried agricultural and craft knowledge across the Atlantic that transformed American “material life,” a concept defined by economic historian Fernand Braudel. In the first volume of his monumental study Civilization and Capitalism, Braudel underscored the significance—then overlooked by most historians—of daily material human needs and economic activities. Looking at economic production in the early modern world, he treated as subjects of historical investigation the foods people ate, the clothes they wore, the tools they used, the markets where they conducted trade, the cities they established, the dwellings they inhabited, and the household furnishings they possessed. Within these structures, human actors lived a “material life,” meaning “the life that man throughout the course of his previous history has made part of his very being, has in some way absorbed into his entrails, turning the experiments and exhilarating experiences of the past into everyday, banal necessities.”1

Given the role that African workers played in material production in the Anglo-American colonies, the concept of material life offers a useful tool with which to explore the historical contexts out of which Africans emerged and to assess their role in New World plantation development. What was the nature of West and West Central African material civilization during the era of the slave trade, how did it come into being, and how did it vary over time and space? What made African material life different from that of other regions of the world? What forces shaped its development? How did Africans perceive the process of material production? This chapter will address these questions, highlighting ways that people in West and West Central Africa produced and reproduced their daily material needs during the height of the Atlantic slave trade. Looking at more than the technical aspects of material production, it will also explore the social, political, and ideological structures through which West and West Central Africans conducted their material lives. In particular, this chapter will demonstrate that Africans acquired a wealth of knowledge through their daily life in urban centers or rural communities, their trading practices and social networks, and their fishing, mining, and artisan practices. The people tragically ensnared by the Atlantic slave trade carried this knowledge with them to the American colonies, and their experience provided them with an important compass to navigate their way through their New World environments.

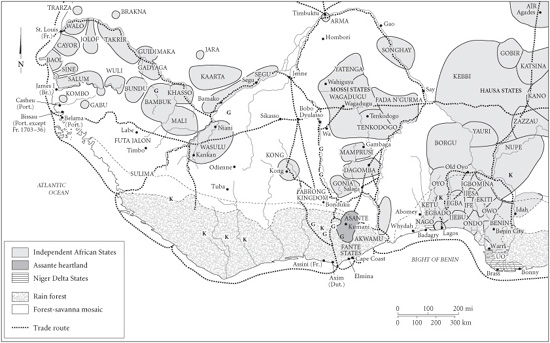

At the advent and during the height of the Atlantic slave trade, European merchants tied into West and West Central Africa’s preestablished social and economic networks. Starting with the gold and pepper trade, they turned to buying slaves on the African Coast. In their log books, ship captains generally labeled their captives as generic commodities.2 However, enslaved Africans emerged from much more dynamic contexts than such terminology suggests. Indeed, African captives had deeply embedded ties with others through local or long-distance trading networks, which underwent significant change during the years of the slave trade. For example, both internal and external factors shaped West African trading networks during the Atlantic slave-trading era. One of the most important internal factors that influenced trading patterns was political decentralization. In 1591, an invasion from Morocco brought the collapse of the Songhay Empire, centered on the Niger Bend. Songhay had previously dominated West Africa’s long-distance trade across the Sahara, which tied the West African forest regions to northern suppliers and markets. Merchants in cities and towns such as Timbuktu, Gao, and Jenne and surrounding plantation complexes along the Niger River facilitated long-range commerce. However, with Songhay’s demise, economic power shifted west into the Senegambia region, south into the forest and coastal zones, and east into Kanem-Bornu. During this period, Muslim merchant associations such as the Wangara, which survived the collapse of the Songhay Empire, moved a variety of commodities throughout West African and other commercial networks.3

Underlying the large-scale commercial networks and long-distance trade of the Wangara and others stood a system of daily market activities carried out by small-scale traders. “Markets were ubiquitous in West Africa,” notes anthropologist Elliot Skinner. “The markets served as local exchange points or nodes, and trade was the vascular system unifying all of West Africa, moving products to and from local markets, larger market centers, and still larger centers.” Small-scale, local traders set up daily markets that offered foodstuffs and other staple goods, while peripatetic traders moved periodic markets from town to town, returning in three-, four-, five-, or sixteen-day intervals. As agents of West African material life, traders facilitated the exchange of material commodities and, more broadly, ideas and “cultural goods.”4

Elites and peasants, agriculturalists and artisans, country folk and town dwellers, and women and men encountered each other daily in these urban and rural trading centers, which allowed people to establish or transgress social and cultural boundaries. For example, at the turn of the seventeenth century, peasants, particularly women, traveled considerable distances to trade between the Gold Coast and its hinterland. The Dutch factor Pieter de Marees recorded that on a market day in Cape Coast

the peasant women are beginning to come to Market with their goods, one bringing a Basket of Oranges or Limes, another Bananas, and Bachovens, [sweet] Potatoes and Yams, a third Millie, Maize, Rice, Manigette, a fourth Chickens, Eggs, bread and such necessaries as people in the Coastal towns need to buy. These articles are sold to the Inhabitants themselves as well as to the Dutch who come from the Ships to buy them. The Inhabitants of the Coastal towns also come to Market with the Goods which they have bought or bartered from the Dutch, one bringing Linen or Cloth, another Knives, polished Beads, Mirrors, Pins, bangles, as well as fish which their Husbands have caught in the Sea. These women and Peasants’ wives very often buy fish and carry it to towns in other Countries, in order to make some profit: thus the fish caught in the Sea is carried well over 100 or 200 miles into the Interior.5

Map 1. West Africa, ca. 1700

Guided by these daily rhythms of exchange, West African women linked specialized areas of food production between the coast and inland. They also acquired knowledge of multiple environments and economic activities.

Whereas women generally carried out the trade in foodstuffs, male traders such as the Wangara plied more prestigious commercial goods. They moved commodities including gold, salt, and kola nuts, used as a stimulant and to abate hunger and thirst, through West African trading corridors. By at least the fifteenth century and into the sixteenth century, the Wangara, an association of Muslim traders from the Niger Bend area, monopolized the trade between North African salt production centers and West African kola nut fields and gold mines. Supplying the external demand for West African gold, merchants mobilized free, slave, or peasant labor in alluvial or pit mines in Bambuk, Bure, Lobi, and the Akan forest gold fields. Adjacent to these gold-mining centers, peasant and slave labor harvested kola nuts that stocked kola markets in the savannah, the Sahel, and the Sahara Desert. Caravans laden with gold and kola nuts moved northward from the forest region. In exchange, caravans loaded with different commodities, including salt from the North African salt mines of Taodeni, Teguida, N’tesemt, Idjil, and Awlil, supplied southern markets. According to one estimate, workers at the production centers in the Lake Chad basin yielded up to thirty thousand tons of salt annually during the sixteenth century, supporting the daily needs of four to five million people.6

Facilitating the flow of commodities, traders exchanged a range of currencies that circulated throughout West Africa’s “vascular system” of trade. Large merchants, small traders, and consumers used different kinds of currencies, including gold, cotton cloth, and iron bars, which were exchangeable at fairly consistent rates over time. At the high tide of the Atlantic slave trade, West Africans used cowry shells from the Maldive Islands in the Indian Ocean as currency. During the eighteenth century, British and Dutch trading firms shipped 25,931,660 pounds of cowries to West Africa, amounting to approximately ten billion shells that entered into the system of trade and circulated throughout the region.7

Through this ongoing process of trade, West Africans tied together production centers, towns, villages, and hamlets. They also acquired experience in managing and transforming the material world, experience that, though intended for local use, took on particular significance within the context of the Atlantic slave trade and New World slave labor camps. Through pathways and “webs” of trade, West Africans brokered and reproduced social and cultural differences. In the process, they reproduced their material lives in mining centers and agricultural fields, in village markets and larger urban settings, through trade in gold or cowries, and by way of local trade or long-distance caravans.8 Hence, when European merchants first arrived on the West African coast in the fifteenth century, they encountered societies with well-established commercial networks. Over the following centuries, the Atlantic trade tapped into, redirected, and prompted changes within these market networks.9

People from Central Africa who were captured in the slave trade came from parallel trading worlds. Most of the exchanges of goods in Central Africa took place on a small scale and were used to cement relationships with people within one’s community. Workers in fishing communities exchanged their catches for staples produced by agricultural labor. Leather workers and cattle herders from the savannah region of Central Africa sent their goods to their northern neighbors. Agriculturalists acquired additional protein by exchanging food staples for the game caught by hunters. Salt, iron, and copper workers found outlets for their products. And while most production was geared toward use within the context of local communities, Central Africans were also bound up in trading relationships with people outside their immediate environs. A small group of people engaged in commerce as their primary occupation, a trade not bound to the ties of community and kinship within which much of the exchange in Central Africa took place.10

The exchange networks of West and Central Africa developed along similar lines, with rotating markets and currencies flowing through each. In the coastal and central regions of southern Central Africa, a four-day market system operated, in which traders traveled to four different market villages over a week. In other places, as for one market along the Zaire River, markets opened once a week. The currencies that flowed through these markets included shells (nzimba) from the Central African coast, raffia cloth (lubongo), and iron bars, a set of currencies comparable to those circulating through West Africa, where people used cotton textiles, iron bars, and later cowry shells as currencies. As a sixteenth-century chronicler of the Congo stated, “Colorful shells the size of chick-peas are used as money. … In other regions, this shell money does not exist. Here they exchange fabrics of the type used for clothing, cocks, or salt, according to what they want to buy.”11 In their encounters with people on the Central African coast and in towns such as Mbanza Kongo, Portuguese merchants tapped into these local networks of patronage and trade.

Map 2. West Central Africa, ca. 1700

The interaction between Central Africans and European traders altered these internal networks. In particular, the massive infusion of trade goods brought in through the Atlantic trade at Luango, Benguela, Luanda, and other Central African ports provided local elites with the means to expand their patronage networks. By distributing foreign rum, imported Asian and European textiles, and other material goods, African patrons expanded their client base and cultivated allies. Access to these new materials created opportunities for the rise of a new elite. In many cases, patrons entered into debt to acquire the goods they needed to expand their retinue, which enabled them to extend their local power base while also making them vulnerable to the demands of creditors. This system of debt became cancerous, as some local elites further extended the system of credit to less powerful vassals. As African patrons and vassals became overextended on foreign credit in the form of trade goods, many saw that their only way to dissolve their debt was to raid for slaves in neighboring territories or to sell people from within their own domain whom they deemed to be expendable. Through such means, the trading networks of West Central Africa were transformed and generated slaves for the Atlantic slave trade.12

In West and West Central Africa, local, regional, and long-distance trading networks linked people across wide expanses, creating a flow of not only material goods but also knowledge. As merchants carried salt from the Sahara Desert into the West African forest, gold and kola nuts from the forest into the Sahara and the Mediterranean World, hides from the Central African savannah to forest agricultural communities, or copper from the Central African mines to its towns and villages, they carried information and ideas about production and the natural world. So people in the regions hit by the Atlantic slave trade had knowledge that was particular to their local social and natural environments, yet they also had an awareness that went beyond what was essential to survive in their immediate surroundings. Out of these environments, networks, and ways of knowing, West and West Central Africans created their material lives.

The web of West African trading relationships connected a population estimated in 1700 to be approximately twenty-five million people, the vast majority of whom lived in rural communities.13 However, trade bound the countryside to urban areas, which had a long history in West Africa.14 Through the confluence of external and internal trade, the towns of Timbuktu, Jenne, Gao, Koumbi-Saleh, Niani, and Kano in the West African savannah emerged in the first and early second millennia AD. Toward the end of this period, towns arose in the south, particularly Begho, on the savannah-forest fringe, and Old Oyo and Benin in the West African forest zone. These towns attracted local trade, linked forest and coastal villages to larger trading networks, and served as “ports” of commerce between the West African forest and savannah-zone economies and the Sahara Desert and Mediterranean World.15 West African urbanization underwent significant change during the years of the Atlantic slave trade. For example, the town of Begho collapsed and Salaga expanded during the eighteenth-century Asante imperial project. Sokoto and the walled town of Katsina grew with the expansion of the Sokoto Caliphate in the early nineteenth century.16 Furthermore, coastal towns such as Cape Coast emerged as centers for the Atlantic trade. In 1655 the Swedes established a fort in the town, which was seized by the British in 1664. Cape Coast’s population grew to approximately three to four thousand people by the early eighteenth century, and its most imposing structure was Cape Coast Castle, which held slaves in its belly in the most wretched of conditions while they awaited a forced passage across the Atlantic.17

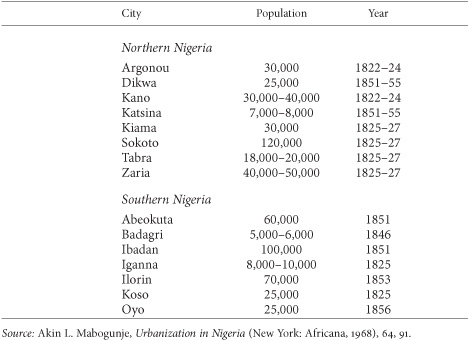

Hundreds of thousands of people lived in towns along the West African coast, in the forests, and on the savannah, as recorded by a number of nineteenth-century accounts. For example, in southern Nigeria in the 1850s the city of Ibadan had an estimated 100,000 inhabitants, and in northern Nigeria in the 1820s the city of Sokoto had an estimated 120,000 inhabitants (see table 1).18

The population figures for West Central Africa similarly are rough estimates; however, the record provides a general indication of the population size of some towns and the region as a whole. Though not as widespread as in West Africa, urbanization emerged in West Central Africa in the early first millennium AD, setting the stage for Portuguese merchants to establish trading partnerships with urban dwellers on their early expeditions to Central Africa in the fifteenth century. In particular, the town of Mbanza Kongo, which became known as Sao Salvador after the arrival of the Portuguese, stood as the economic, political, and religious center of the Kingdom of Kongo. Rising in approximately the fourteenth century, Mbanza Kongo grew with the kingdom and eventually surpassed other Central African towns in population and territory.19 By around 1630 the town was home to a population of approximately sixty thousand people. In addition, the new Portuguese trading settlement of Loango, like Cape Coast on the Gold Coast, had a population of several thousand people. Smaller towns, which were essentially clusters of villages, had populations between one and two thousand people. These clusters of people stood in the midst of an overall population of ten to twenty million people in West Central Africa during the years of the slave trade.20

TABLE 1

Estimated Population of Nigerian Towns, 1822–1856

While people in the towns defined themselves above and against their more rural counterparts, the boundaries between the urban and rural could be porous. For instance, many of the people who lived in Mbanza Kongo farmed within the town’s limits.21 Around the town of Begho, agricultural workers maintained a strong “hunting ethic,” and people relied upon fishing, gathering wild plants, and trapping animals for much of their caloric intake.22 So people in West and West Central African cities and towns interacted across boundaries, worked in multiple economic fields, established local and regional networks, and remained tied to people in the rural hinterlands. Nevertheless, people who lived exclusively in the countryside lived qualitatively different lives from those of their more urban counterparts, who in many cases were protected by a series of walled structures, a prevalent feature of many African towns. For instance, from the eleventh into the nineteenth century, generations of workers constructed and maintained the walls that enclosed the town of Kano. This defensive shield enabled the local elite to more effectively collect revenue, the military to defend urban inhabitants against attack, craft workers to protect their workshops, and the population at large to secure their agricultural fields, craft industries, and food supplies during periods of military siege.23 Like the West African walled towns, Mbanza Kongo was surrounded by a palisade, and the African Catholic King Afonso I had his subjects add a stone wall to surround the royal and Portuguese quarters in the early sixteenth century.24 The Portuguese priest Duarte Lopes wrote then about Sao Salvador that “the town is … open to the south. It was Dom Afonso, the first Christian king, who surrounded it with walls. He reserved for the Portuguese a place also surrounded by walls. He also had his palace and the royal houses enclosed, leaving between these two enclosures a large open space where the main church was built.”25

Town walls instantiated social hierarchies, ways of accessing power, and forms of labor organization, as in the West African town of Benin. Within Benin’s town walls, urban workers organized along craft lines. Farmers, hunters, traders, soap makers, metalworkers in iron or brass, woodcarvers, potters, bead makers, basket, mat, and textile weavers, dyers, tailors, dressmakers, hairdressers, musicians, medicine makers, administrators, domestic servants, and carriers plied their trades on the streets of Benin.26 To monopolize their crafts, many of them joined trade guilds, and guild members usually lived in distinct villages, quarters, or town wards. Through these associations, normally composed of family members but open to anyone willing to undergo an apprenticeship, craft workers “were able to control the production of goods, fix prices and also punish guildsmen who violated guild rules.”27 Guilds were not exclusive to West Africa but also became a means by which Central Africans organized labor. Before the Atlantic slave trade, Central African hunters formed protective associations through lineages to shield their crops and settlements. They subsequently organized into guilds to lead the hunt and distribute their game when the Atlantic trade opened opportunities to sell ivory tusks. After giving local rulers and arms dealers their share of the kill, they controlled the sale of the balance to European merchants.28

In contrast to the guild system of Lower Guinea and Central Africa, craft workers in Upper Guinea belonged to caste groups.29 Oral traditions collected during the twentieth century recount that generation after generation passed work practices through caste lines. Individual workers within the major caste groups—smiths, weavers, leather workers, and woodcarvers—specialized in particular kinds of work. Some smiths extracted ore and smelted iron, some forged iron but did not extract ore, and others, usually royal artisans, worked in precious metals, producing gold jewelry and sculptures cast in brass. Some weavers manufactured strips of white cloth; some, known as “kerka” weavers, produced “huge blankets, mosquito nets and cotton hangings” covered with symbolic motifs; and others manufactured cloths with designs based on their knowledge of mathematics and cosmology. Some woodcarvers made sacred sculptures and mortars and pestles out of particular kinds of wood, some built household items and furniture, and some made canoes. Some leather workers specialized in making shoes, some made “straps, reins, bridles, etc.,” and others made “saddles, horse collars, etc.” The fruits of their labor not only supplied the subsistence needs of farmers and political elites but also entered the market system that connected rural settlements and towns of Upper Guinea with larger trading networks.30

Through their networks, West African merchants and political leaders administered trade from the cities and maintained commercial ties with leaders in other towns and cities. For example, after a jihad established the Sokoto Caliphate in northern Nigeria in the first decade of the nineteenth century, its leadership developed regular trading relationships with the south. An early sultan of Sokoto Caliphate, Muhammad Bello, described his empire’s commerce with the southern Yoruba-speaking people, observing in 1824, “Yoruba is an extensive province containing rivers, forests, sands, and mountains, as also many wonderful and extraordinary things. … By the side of this province there is an anchorage or harbour for the ships of the Christians, who used to go there and purchase slaves. These slaves were exported from our country and sold to the people of Yarba [Yoruba], who resold them to the Christians.”31 This process of trade exported to the “Christians” people who were not merely “slaves” but, though the Atlantic traders might not know it, people with a wide range of practical knowledge of material production.

Whether in empires with large towns or in kinship-based modes of production composed of small villages, “few West African societies were without craftsmen.”32 Their abilities to make tools and extract energy from the natural world made them vital agents in the production of West African material life. Craft workers negotiated within and around frameworks of social hierarchy and power, urban and rural development, and production and trade. They also mastered particular kinds of work skills, inherited and transmitted specialized forms of craft knowledge, maintained clear gender divisions of labor, and managed different scales of production. They worked in different contexts, ranging from rural, small-scale production sites for household and local consumption to urban, large-scale production centers that satisfied tributary obligations or supplied regional markets. And as in other premodern societies, work often carried with it a sacred dimension. Essential participants in precolonial West African life, many West African craft workers were ensnared in wars or enslaved through some other means and sent to the Americas through the Atlantic slave trade.

During the eighteenth century, one of the most important sources of slave labor for the British colonies was the Gold Coast of West Africa. While in the previous century the Gold Coast had been a net importer of slaves who toiled in the region’s gold mines, cultivated its farmlands, and carried head-loaded goods along its trading routes, in the late seventeenth century the coast’s slave-trading pattern changed with the rise of the Asante Empire.33 During its expansion, the Asante conquered neighboring states and kinship-based societies and imposed tributary relationships upon its subject territories. The Asante had their foreign subjects work in agricultural fields, set up craft workshops, or march to the coast to be sold to Atlantic slavers. In the eighteenth century, the Asante’s armies invaded northern territories and left behind vassal states. Marching northward, the Asante captured territory under the control of the Banda chieftaincy, a largely rural network of agriculturalists and artisans. The Asante attacked the region in 1733 and brought it under their control in 1773, taking possession of the agricultural and craft production centers of the region. Among the workers co-opted or captured and sold by the Asante were women potters skilled in making vessels for storage, cooking, eating, and other quotidian needs.34 The Asante also conquered the northern states of Gonja and Dagomba, which regularly supplied slaves to the Asante. Pressured to deliver its tribute in slaves to the Asante, the Dagomba state in turn waged wars against neighboring societies to acquire captives. In the mid∇nineteenth century and probably earlier as well, they invaded the Bassar region to the east in modern Togo. During such periodic raids, captives from Bassar unwillingly passed through the political fields of the Dagomba and Asante and entered the slave trade.35

During this era, workers in the Bassar region operated a large-scale metalworking complex, divided into iron-smelting, iron-smithing, charcoal-making, pottery-making, and leather-working villages. The iron ore∇rich region included the iron-smelting towns of Bassar, Kabu, Bitch-abe, and Bandjeli. In the large-scale smelting operation in Bandjeli, organized according to skills and gender divisions of labor, women mined and transported ore from the mines, while men smelted it into iron bloom. Smelters traded the bloom to blacksmithing villages, where both men and women engaged in production. Women pounded the bloom in stone mortars to remove the impurities and then mixed the iron with clay and vegetable fiber. Men working their blacksmith forges fashioned the iron “into hoes, axes, arrowheads, knives, spears, ceremonial bells, and smelting and smithing tools.”36

Ironworkers plied their trade in dynamic political, cultural, and environmental contexts. Workers called in ancestral spirits when transforming the ore, and the gender divisions of labor were reflected in their craft symbols. For example, male smelters likened their forges to wombs and felt ambivalent toward women. While fearing women’s sexuality, they revered their reproductive capacity as analogous to the creative process of ironworking.37 Pressed by external demand, Bassar ironworkers supplied a wide regional trading network, and their industry had a significant environmental impact. In particular, they risked deforestation from overconsuming trees to fuel their iron furnaces. From the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, Bassar expanded production before declining in the face of European competition. At its height, the Bassar trading zone included all of Togo, much of eastern Ghana, and portions of western Benin, covering approximately one hundred thousand square kilometers (38,500 square miles). According to archeologist Philip de Barros, “In terms of people being served, the Bassar trade zone may represent the servicing of a population of well over 600,000,” including the Asante Empire, which in its expansion during the eighteenth century increased its demand for iron.38 Producing iron bars not only for tools crafted by local blacksmiths but also for currency, the labor of Bassar metalworkers fostered regional economic development on a number of levels. And they were part of a larger sphere of African ironworkers.39

Like the Bassar ironworkers, Gold Coast fishers served regional markets. They practiced a wide range of skills, managed daily, weekly, and seasonal rhythms, organized labor, negotiated political obligations with local elites, and supplied regional trading partners. From the seventeenth into the eighteenth century, the Gold Coast fishing trade was concentrated in a number of towns, including Cape Coast, Mouri, Kommenda, Kormantin, and Elmina. Off Elmina’s shores, coastal fishermen manned around five to eight hundred canoes, which left to fish every morning except Tuesday, the day of rest. Propelled by one or more paddlers paced by the rhythm of work songs, they ventured one or two leagues offshore. Deep-sea fishing teams fished at night, luring fish with torches and catching them with harpoons. In the mornings of January, February, and March, they sailed miles offshore and used lines made of fiber drawn from tree trunks, attached with three or four baited hooks that caught small fish. Close to shore during the nights of October and November, they cast nets of twenty fathoms in length and retrieved them in the morning, before dawn. Others ventured on foot into the ocean at night with a torch in one hand and a basket in the other to catch fish. Pairs of fishermen waded waist-deep into Gold Coast lagoons, marshes, and rivers to sweep handheld nets through the water. After paying tax in kind and allocating fish for local consumption, traders from the fishing communities marketed the balance to inland farmers in exchange for maize, millet, rice, or other commodities.40

People on the Gold Coast learned fishing practices at an early age, gradually acquiring more knowledge about their craft over time. Pieter de Marees observed at the turn of the seventeenth century that cohorts of young males went through an apprenticeship in their craft. Boys between the ages of eight and ten would learn how to “make nets; and once they know how to make nets, they go with their Fathers to the sea to Fish.” Before marrying, two or three young men would live together, “buy or hire a Canoe … and set out to fish together.”41 Through the course of their work, they acquired not only expertise with the tools of their trade but also a wider knowledge of the environment. They knew the names of scores of fish, and their knowledge also extended skyward.42 According to one source, a coastal fisherman’s knowledge “was certainly extensive, for he could not only give names for the principal planets, constellations and fixed stars, but could also tell what seasonal and meteorological conditions prevailed when they were visible.”43

In this respect fishermen along the Gold Coast were not unusual among West African coastal workers. In the mid∇eighteenth century, the Frenchman Michel Adanson, a correspondent to the Royal Academy of Sciences, recalled that people on the Upper Guinea Coast “pointed to me a considerable number of the stars, that form the chief constellations, as Leo, Scorpio, Aquila, Pegasus, Orion, Sirius, Procyon, Sirius, Spica, Coanopus, besides most of the planets, wherewith they were well acquainted. Nay, they went so far, as to distinguish the scintillation of the stars, which at that time began to be visible to the eye.”44 Such knowledge had multiple layers—it provided practical guidance for fishermen who ventured to the sea at night, and it also gave them access to forms of spiritual power. Reminded by the winds and waves of the ocean, the life force in the fish, the solidness of the wood in their canoes, the darkness of the night, and the light of the stars, they experienced their fishing not simply as a daily activity but at times as a sacred practice.45

Located at the juncture between the realms of the sky, land, and sea, workers in fishing communities were also connected to the labor of local woodworkers, whose skills included timber cutting and canoe building. From the seventeenth into the nineteenth century, woodworkers played important roles in the Gold Coast’s material life. In the Birim River Valley, woodworkers drew upon the region’s supply of silk cotton trees as raw material to craft military and commercial canoes.46 At Takoradi, one of the leading canoe-building centers on the Gold Coast in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, woodworkers felled trees from their forest hinterland and manufactured dugouts measuring up to thirty feet long and eight feet wide. Meeting the needs of more than the fishing trade, woodworkers also supplied the commercial and political needs of a coastal society that engaged in long-distance sea trade and extensive military operations. Jean Barbot noted in the late seventeenth century that coastal seacraft had the ability to “carry above ten tun of goods, with eighteen or twenty blacks to paddle them,” and that the military canoes held approximately “fifty or sixty men, besides ammunition and provisions for fifteen days.” He added, “Those Blacks manage them with such extraordinary dexterity in the most dangerous places that it is much to be admired.”47

Facing the danger of the ocean currents and respecting the Atlantic’s power to supply material sustenance yet also take life, coastal fishermen created rituals and symbols of reverence and protection for their work. Relying on more than their “dexterity,” the fishers invoked ancestral spirits to support and guide them through the process of material production. In recognition of and supplication to their ancestors, they would “often paint and colour” their canoes or “drape them with ears of Millie and Corn.”48 Contributing their labor to flourishing local and regional trades that connected them to a larger material civilization, Gold Coast fishing and woodworking communities viewed their material life in nonmaterial and symbolic ways, maintaining perspectives and ideas about work and the natural world that captives in the slave trade carried across the Atlantic.

Like craft workers in West Africa, Central African artisans fashioned their material life out of the raw goods of their locales, facing the limitations, tapping into the potential, and making something new of their environments. As in most of the West African forest region, sleeping sickness kept Central Africans from raising large numbers of livestock. However, in parallel to the cattle production in the West African savannah, pastoralists in the Central African southern savannah raised herds of livestock. The Portuguese merchant Pieter Van Den Broecke wrote after landing on the River Congo in the early seventeenth century, “Along the way we saw a large numbers of stock, for example wild animals such as hart, hind, field-fowl, wild pigs, and others too; and particularly, many oxen, cows, sheep, and goats, which were pastured in flocks of 100 by herdsmen.”49 In addition to herding livestock, savannah agro-pastoralists made leathers and hides, finding markets to the north.50 Hides were among the many goods that circulated in Central African trading networks. Another important trade item was salt. Salt miners extracted the substance from different sites in Central Africa, one of the most important being at Kisama, located south of the Kwanza River, nearly thirty miles from the ocean. In the savannah, salt workers “cultivated salty grasses in marshes, burned them, and filtered the ashes to obtain crystals after evaporation.” On the coast and rivers, workers made salt by extracting it from the beds of receded riverbanks or by evaporating saltwater from the Atlantic.51

Central African workers made craft goods that remained within networks of household and village exchange or that entered into a broader context. On an everyday level, woodworkers crafted tools for agricultural production, but they also had the skill to carve masks for initiation ceremonies of young boys and girls into adulthood, for divination and healing, for agricultural rituals, and for other occasions.52 Some artisans became more specialized. With the increase in locally grown and imported tobacco, the demands for locally produced tobacco pipes increased, prompting a shift in the division of labor for pipe makers. Labor became increasingly segmented, with wooden pipe makers increasing their efficiency by having one group of workers craft the stem and another focus on the bowls.53 Within agricultural communities that produced primarily for local consumption or in craft production centers oriented toward trade, people acquired a mastery of woodworking.

As was true along the Gold Coast and other parts of West Africa, woodworking in Central Africa was tied into other kinds of labor, particularly that of fishermen who daily ventured off the Central African coast in dugout canoes. Van Den Broecke recounted about people near the coastal town of Loango, “The natives are very good fishermen and catch great numbers of fish. There, in the morning, sometimes more than 300 manned canoes go out to sea, and return to land at midday at the height of the sun.”54 Others in West Central Africa tapped the ocean and rivers with harpoons, lines, and nets. Like Gold Coast workers, people in Central African fishing communities ritualized their labor. They worked as clients of local religious and political authorities, to whom they provided an offering before sending their fish to local or more distant markets. According to one account of a fishing community subject to a “countess,” “the first fish they catch is immediately sent to the countess, who must prepare it with her own hands. … When they reach their village, they eat the fish cooked by the countess, after which they abandon themselves to their customary leaping and rejoicing. After these ceremonies they look forward to a great abundance of fish and the enjoyment of all prosperity.”55

The most important and deeply respected of artisans were the metallurgists, who worked in either iron or copper.56 Iron deposits were scattered in Central Africa, particularly in the forests and western mountains, and miners, smelters, and smiths set up regional production centers to transform the ore into metal wares. Artisans made a range of products, including knives, axes, and weapons, and the hoes and iron bars crafted by metalworkers were most in demand and constituted vital trade goods in local and regional networks of exchange.57 The region also yielded copper, drawing the attention of European merchants on the coast. Van Den Broecke recalled, “There is also much beautiful red copper, most of which comes from the kingdom of the Insiques (who are at war with Loango) in the form of large copper arm-rings.”58 The rings were a final product of a multistage process, in which men mined the rich copper ore deposits at sites such as Bembe, which was about seventy miles south of Mbanza Kongo. Women and young people washed and sorted the ore, and men smelted and crafted the copper into its ultimate form. Through these gender divisions of labor, copper entered West Central African networks, fostered the flow of goods, and cemented social ties between people through gift-giving practices.59

As African potters, spinners, woodworkers, and smiths refined raw materials into practical and aesthetic objects, these workers simultaneously transformed their own minds and bodies. Through their labor in the mines and workshops, along the coasts and rivers, and in their housing compounds and adjoining forests, African workers developed a body of knowledge and passed it on to their youth. Young girls learned the craft of pottery from older women making it in their courtyards, and young boys, such as Camara Laye, stood in awe of their fathers who had mastered the art of smelting iron or gold.60 And while youth were geared toward working within gender divisions of labor, boys might learn something of the crafts performed primarily by women by sitting at their feet, just as girls might catch glimpses of the work done primarily by men. While engaging in work or observing others, they acquired “wealth in knowledge.” As Jane Guyer and Samuel M. Eno Belinga argue about Equatorial Africa, people had knowledge “in the arts, music, dance, rhetoric, and the spiritual life as well as hunting, gathering, fishing, cultivation, raffia-weaving, wood-carving and metallurgy.”61

When merchants from Europe anchored off the coast of West and West Central Africa, they caught a glimpse of the African labor force and their material life. The people whom European merchants encountered along the coast embodied practical knowledge of material production, which involved mastery of the Atlantic coastal currents, fishing, carpentry, metalworking for the tools that carved out the seacraft, lumberjacking to fell the trees for the canoes, agricultural production in coastal and inland communities, and trading practices that tied this knowledge into markets. Their daily life involved setting up apprenticeships, respecting client-patron ties, drawing strength in work through song, naming the bodies of nature from stars to the animal world, and viewing the sacred dimensions of nature and work. This “body of knowledge” was not limited to people along the coast. Experienced with a practical set of skills to manage their environments, people from Africa bought by Atlantic slavers possessed, collectively, a wealth of knowledge. And though the vast majority of them remain nameless in the historical record, they played a considerable role in the New World settings that they entered.