West African Indigo Workers in the Atlantic World to 1800

The forests gave way before them, and extensive verdant fields, richly clothed with produce, rose up as by magic before these hardy sons [and daughters] of toil. … Being farmers, mechanics, laborers and traders in their own country, they required little or no instruction in these various pursuits.

—Martin Delany, The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and

Destiny of the Colored People of the United States (1852)

Between 1740 and 1770, colonial South Carolina emerged as one of Great Britain’s principal suppliers of indigo, used foremost as a blue textile dye. In 1750, South Carolina exported approximately eighty-seven thousand pounds of indigo, which soon gained a reputation as a middle-grade commodity, next in quality to the highest grade produced in Guatemala and the French Caribbean. Between midcentury and the American Revolution, a period that coincided with an increased importation of enslaved workers from West Africa, the colony’s indigo exports expanded more than tenfold to over one million pounds per year.1 How did this transformation happen? What factors shaped the development of indigo production in colonial South Carolina? In what ways did indigo shape colonial South Carolina? What were the legacies of indigo production in South Carolina? This chapter will address these questions by viewing South Carolina indigo plantations within the contexts of British commercial expansion and the larger Atlantic World, examining the role that West African indigo workers played in their development, and considering their historical legacies, including material and ideological ones.

Among the ideological consequences of the development of South Carolina indigo plantations has been the depiction of Eliza Lucas Pinckney as the principal agent of indigo production in South Carolina. For instance, according to the agricultural historian Lewis Cecil Gray, whom many later researchers have followed, “The credit for initiating the [indigo] industry is due Eliza Lucas, who had recently come from the West Indies to South Carolina, where she resided on an estate belonging to her father, then governor of Antigua.”2 One colonial historian has written, “Eliza Lucas (later Pinckney) especially labored to introduce West Indian indigo cultivation.” Furthermore, this scholar argues that Lucas was one of many innovators “within a wider network that included Carolinians, West Indians, and Britons.”3 As the mother of American revolutionary heroes Thomas Pinckney and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, Eliza Lucas has been the subject of biographies, children’s books, and a novel for her reputation as an innovator in indigo and a mother of the American Revolution.4 Such depictions make the slave labor force invisible, leading one prominent authority on American slavery to state, “Unlike the Africans who had grown rice prior to their capture, the slaves assigned to indigo production brought no knowledge of the task with them to the New World and often had to be directed by white artisans; still their on the job training gave them a special expertise in the intricacies of making the blue dye.”5 These interpretations obscure a number of important factors that led to the development of indigo in South Carolina, a process related to rice production.

While the colony struggled for decades to find a viable export comparable to Caribbean sugar, it found a saving grace in rice, a crop that African workers transplanted into the colony’s soil.6 As rice took off, colonial planters had the means to buy even more slaves. With increasing flows of labor from Central and West Africa and expanding exports of rice, coastal South Carolina attracted planters and prospective planters, and the Lucas family entered the colony in this spirit. By 1713, John Lucas of Antigua owned in absentia a number of Carolina rice plantations. In 1738, John Lucas’s son George left Antigua to live in South Carolina. His political aspirations soon called George Lucas back to Antigua, where he served as its governor, leaving his daughter Eliza with the authority to manage his property for him. She managed three plantation sites: one at Wappoo, where the family lived; one at Garden Hill on the Combahee River, a fifteen-hundred acre property that produced pitch, salt pork, tar, and other commodities; and one, a three-thousand acre rice plantation, on the Waccamaw River.7 As noted earlier, a number of sources credit Eliza Lucas with developing indigo into a major cash crop in South Carolina. Though previous generations in South Carolina had tried and failed to do so, her estate sustained indigo production and offered resources and models for neighboring plantations. The Lucas plantation was significant; however, the innovations that occurred there and elsewhere in South Carolina can best be explained by broadening the field of view. Other factors that enabled the rise of the colony’s indigo industry included changes in the supply structure of indigo to Great Britain from India, inputs of knowledge from India, West Africa, and the Caribbean, and the opportunities created by a wartime crisis.

Hoping to add to their supply of indigo from India, the British turned to the Americas for the dye, which they sought to export along with other staple crops. Shortly after British colonial settlement on the island of Bermuda, colonists planned to develop indigo. For instance, the colonist Robert Rich set English laborers to work on indigo plants in his garden, though he admitted, “I stand in great need of one whose judgment is better than my one [sic], for the making of it.” He requested written instructions about the crop; however, it never became a major cash crop on the island.8 It did become a cash crop shortly after the British claimed Barbados, which, within its first two decades under colonial rule, produced indigo for export. By the 1640s, Dutch traders in Barbados bought indigo with slaves, some of whom, ironically, produced more indigo for export. In spite of the sugar revolution at midcentury that transformed the Barbados export economy, the island continued to produce small amounts of indigo into the 1660s. As either the secondary or primary labor force, Africans in Barbados cultivated and processed indigo, a labor-intensive crop.9 And many of them carried knowledge of indigo across the Atlantic, which fostered the development of the dye in Barbados and elsewhere in the Anglo-American world.

At the inception of the Atlantic slave trade, West Africa was one of many indigo manufacturing centers in the world. In addition to southern Europe, India, China, South America, and other areas, Africa had a long history of indigo production during the early modern era. Archeological research has uncovered fragments of indigo-dyed blue textiles that date indigo production in what is now Mali to at least the eleventh to twelfth century AD. For centuries, blue textiles were used to clothe not only the living but also those who had recently passed into the ancestral realm. Their physical remains, preserved for eight to nine centuries in the caves of Mali’s Bandiagara Cliffs in the Dogon region, testify to the long history of indigo production in West Africa.10 This early tradition established precedents for later developments in West Africa, and plantation owners in the Atlantic World tapped into this pool of knowledge.

During the years of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, indigo was developed throughout West Africa despite the disruptions caused by the traffic in human cargo and the influence of European imports on West African industries. In some cases, Atlantic commerce clearly influenced the development of West African textile production. For instance, some West African textile workers added a novel dimension to their craft by weaving thread from imported textiles into their cloths. In the late seventeenth century, the Englishman Thomas Phillips, who was on the west coast of Africa in the late seventeenth century, remarked, “The Whidaw cloth is about two yards long, and about a quarter of a yard broad, three such being commonly joined together. It is of divers colours, but generally white and blue. … To make these Cloths, especially the blue streaks, they unravel most of the sayes and perpetuanoes we sell them.”11 By the mid∇seventeenth century, European and Asian textiles shaped African textile production, yet as noted earlier the imports were unable to dislodge West Africa’s textile industry. At this time, imports constituted only 2 percent of West Africa’s clothing needs, and indigenous textile production far overshadowed the influence of European imports.12 This was not lost on European merchants, many of whom sought to tap into West Africa’s textile and related crafts. For example, as early as the mid∇sixteenth century, Portuguese merchants initiated an indigo trade on the coast of Sierra Leone.13

Though West Africans used different kinds of dyes in their cotton textile industries, the most prevalent was indigo, sustaining the production of blue fabrics in a number of cloth production centers. Concerning textile production in Benin, the Dutchman David van Nyendael wrote at the turn of the eighteenth century, “The Inhabitants are very well skill’d in making several sorts of Dyes, as Green, Blue, Black, Red and Yellow; the Blue they prepare from Indigo, which grows here.” Also, representing the Dutch West India Company in the early eighteenth century, Ph. Eyten observed indigo for sale in the Slave Coast port town of Whydah.14 In the early seventeenth century, Pieter de Marees noted that in Senegal the male elders would “wear a long cotton Shirt, closed all around, made like a woman’s chemise and with blue stripes,” a style also prominent among elites in Ardra, as surviving textiles from the mid∇seventeenth century show. On the basis of firsthand accounts of mid-seventeenth-century Benin, the Dutch geographer Olfert Dapper remarked, “The women wear over the lower part of their body a blue cloth, coming to below their calves.” And in the interior town of Jenne, it was reported, “the Priests and Doctors wear white Apparel, and for distinction all the rest wear black or blew Cotton.”15 The prevalence of blue textiles, from Senegambia to the Slave Coast and into interior regions, reveals the wide distribution of indigo production throughout West Africa.

Agriculturalists who raised indigo cultivated it in tandem with other crops. In particular, it was commonplace for rice cultivators to grow indigo, which often stood in the fields next to cotton. The landscape of West Africa’s rice region, which varied from the damp floodplains and swamps to drier upland fields, accommodated indigo cultivation, which is suited to drier soils. Several eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sources testify to the relationship between these crops. Michel Adanson, a French naturalist who surveyed the geography of the Senegambia region in the mid∇eighteenth century, observed, “The higher grounds were covered with millet; and there also the indigo and cotton plants displayed a most lovely verdure.” In contrast, rice was “almost the only grain sown at Gambia in the lands overflown by the rains of the high season. The negroes cut all these lands with small causeys, which with-hold the waters in such a manner, that their rice is always moistened.”16

These patterns continued into the following century, as rice fed into indigo production. After the Frenchman Gaspar Mollien passed through the state of Futa Toro in the early nineteenth century, he noted that the crops included “large and small millet, cotton, which is very fine, excellent rice, indigo, and tobacco.” He added that “the country comprised between the Rio Grande, the Gambia and the river Geba, bears the name of Kabou; it is very fertile; the inhabitants cultivate rice, millet, and maize, and a little indigo and cotton.” Richard Lander noted that from Boosa “the soil improved greatly as we drew near Yaoorie; and immense patches of land, cultivated with a variety of corn, also with rice, indigo, cotton, etc., were attended by a drummer, that they might be excited by the sound of his instrument to work well and briskly.” Clearly, rice cultivation was often bound to indigo.17

Agricultural workers used similar methods to process cereal crops and indigo. Rice and millet growers, particularly women, used mortar and pestles to remove rice grains from their hulls, and they employed similar techniques for indigo production.18 This was the case in the Senegambia region, according to a number of accounts. Adanson remarked that after the indigo was harvested, workers pounded the leaves “in a mortar to reduce them to paste.”19 According to William Littleton, a commercial agent who worked on the Senegambia coast for eleven years during the eighteenth century, workers would first cultivate indigo and then “cut it, pound it in a wooden mortar, and hang it up in the form of sugar loaves.” Cultivating and then transforming the indigo leaves into indigo balls was one step in the dyeing process.20

The final production of blue textiles required a number of other techniques and tools, and the indigo, after being pounded in the mortar and dried, went through another phase before it was ready for use. To turn the leaf into a dye, Africans fermented indigo in an alkaline solution of ash water. The Dutch merchant Ph. Eyten recounted in the early eighteenth century that in the village of Keta, on the border of the Gold and Slave Coasts, “they first soak the leaves and then make balls of them about the size of a fist, which they then put away. In this way, they seem to keep them in a good condition for more than a month.”21 In the eighteenth century, the British factor William Littleton added a more detailed description of this process. After the indigo was pounded, indigo workers would “infuse it in water, or a lye made of ashes.” To make the solution, they burned wood, ash used for cooking, and ash and ash water left over from previous dyeing on a sieve in a clay kiln. Next, they placed wood, old indigo leaves, and the ashes in a pot that had a hole in the bottom. Into this pot, which sat atop another pot with a hole in its side, they poured water that dissolved the salt from the ashes and passed through the bottom hole. Craft workers collected the ash water in a pot that they placed through the side of the bottom pot and transferred the water to a dyeing pot or vat. They then dissolved the indigo balls in the solution, readying the vat for dyeing.22

As with rice cultivation and processing technologies, indigo was produced through gendered divisions of labor, and, though in some places men dominated the craft of dyeing, indigo production and the dyeing process throughout much of West Africa were women’s arts. This was noted in the late eighteenth century by Mungo Park in the Senegambia region, where women monopolized indigo dyeing, a division of labor that endured into the following centuries and transformed under pressures of colonial rule.23 Requiring agricultural development, woodcarving, pottery production, and other kinds of work skills, West Africa’s indigo and blue textile industries represented several layers of knowledge. The Atlantic slave trade swept through these areas of West Africa, carrying people with experience in indigo production to the Atlantic islands, the Caribbean, and the North American mainland. It is possible that indigo, though a secondary crop, had a wider distribution in West Africa than rice, given that it was grown from the Senegambia region to the Bight of Biafra and from the forest zone to the savannah. West Africans counted blue textiles as part of their material life, so the alchemy of indigo would not have been a mystery to slaves held captive on Atlantic World plantations.

Whether involved directly in their development or indirectly through trading or other kinds of relationships, West Africans carried indigo production knowledge systems into the Atlantic. Slaves grew the crop in the Atlantic Cape Verde Islands in the early eighteenth century. As in West Africa, indigo workers made the dye “by pounding the Leaves of the Shrub, while green, in a wooden Mortar, such as they use to pound their Maiz in … and so reduce it to a kind of Pap, which they form into thick round Cakes, some into Balls, and drying it, keep it ’till they have Occasion to use it for dying their Cloths.”24 However, it would remain a minor crop on the island; colonial indigo production was much more important in the Americas, being launched there in the sixteenth century by the Spanish and expanded by the French and the British in the seventeenth.

Anglo-American colonial indigo development arose through the global movement of people, seeds, commodities, and ideas, and the British tried to create opportunities that they witnessed others reap. With the Dutch East Indies Company and the Spanish getting a jump on the global indigo and blue textile trade in East Asia and the Americas, England sought as early as the late sixteenth century to compete, entering along with the French and Dutch into trade in the Levant and trying indigo on small scales in different colonial American settings. The Spanish, deploying Indian and African labor, set up indigo workshops, or obrajes de tinta, a model that other colonists would follow, particularly on the island of Barbados.25 For its labor supply, Barbados turned to Dutch slavers, who in the mid∇seventeenth century delivered the majority of the island’s African workers. In particular, the Dutch operated a lucrative traffic in slaves from the indigo- and textile-rich Senegambia region to Barbados plantations.26

By the mid∇seventeenth century, indigo production expanded in Barbados, and its African laborers transferred their knowledge of the crop and related woodworking skills to the island. The testimony of Felix Christian Spoeri, when compared to contemporary accounts from West Africa, reveals this process. Having worked on the island as a doctor and veterinarian for brief spells in 1661 and 1662, Spoeri noted that after indigo was cultivated and harvested, “the plant is put in hollowed-out trees or troughs and water is poured over it. They let it lie there until it is quite soft and smooth, and then pound it with pestles until all is crushed.” He continued, “Then they strain it and fully press out the left overs. The juice is then poured up to a hand’s width high, into clean vessels, and is dried in the sun.”27 The development of indigo in Barbados, in part a result of the experience of West African workers, helped buoy the confidence of British colonists in the crop’s viability, needed because of previous failures with the crop.28

By the 1670s, indigo faded to relative insignificance in Barbados as the island was swept up in the sugar revolution that made it, according to one source, “Crown and Front of all ye Carooby Islands.” From the late seventeenth into the eighteenth century, most other British Caribbean islands also became dominated by sugar plantation barons. With capital converted from trading or small-scale farming and with credit extended by Dutch or English merchants, the sugar revolution recurred throughout the Caribbean. The islands received a steady influx of enslaved African workers who supplanted indentured servants, replaced those who perished from disease or the rigors of forced labor, and changed the labor force’s size and character.29 On many of the islands, sugar was nearly as important as it was in Barbados, yet planters elsewhere in the British Caribbean continued to see indigo as a viable secondary export crop.

Within the first decade of the British occupation of Jamaica in 1655, the island included indigo among its exports, a product cultivated by both black and white workers. Early Jamaica had a small slave labor force that worked in the fields next to indentured servants. And while the early African population of other colonies such as Barbados consisted of both West and Central Africans, imports of slaves to Jamaica came primarily from West Africa, particularly from the Slave Coast and the Bights of Benin and Biafra. Because it could not absorb the approximately 3,800 slaves imported into the island between 1656 and 1665, many were dispersed to other islands. Yet by 1662 hundreds of slaves populated the island, toiled alongside indentured servants, cleared the forests, and cultivated indigo and other crops for export or subsistence. With the allure of profits from the dye, Jamaican elites invested in slaves and indigo production technologies, so that in the final two decades of the century and into the next, indigo exports steadily increased in volume.30

By the late seventeenth century, when sugar production expanded on the island, Jamaican landowners without enough capital to invest in sugar enterprises made smaller investments in indigo production. This became particularly important to the mother country, given changes in the structure of indigo production in India, one of England’s principal indigo suppliers in the seventeenth century. The cost of indigo in India went up in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. This happened in part because of increased demand for indigo in Indian and Middle Eastern textile industries and also because of increases in road tolls and tribute collected from peasants.31

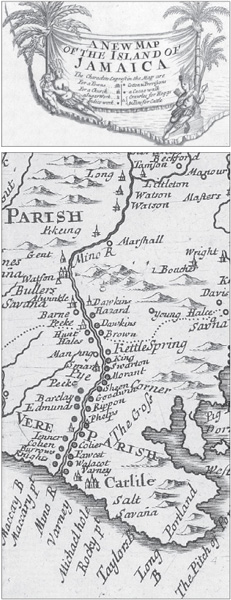

Searching for cheaper indigo, the English looked to Jamaica and other Caribbean islands to meet their demands. In 1671, Jamaican sugar works numbered fifty-seven, and during the rest of the seventeenth and into the eighteenth century sugar and its by-products remained Jamaica’s largest and most lucrative export. Yet amid the island’s sugar-fed transformation with a substantially larger African population, Jamaica continued to include indigo among its exports. From 1671 to 1684, the number of indigo plantations increased from nineteen to forty, with many of them concentrated in Clarendon Parish, along the Mino River (see figure 1).32

Jamaican indigo plantations raised two kinds of indigo, some of which also grew in West African agricultural fields. The first, labeled “French” indigo, was Indigofera tinctoria. Grown throughout the Mediterranean World and western Asia, I. tinctoria was one of the many crops that crossed the Atlantic during the colonial era. More important in Jamaica than “French” indigo, a plant called “Guatimala” by some contemporaries yielded higher-quality indigo. Guatimala indigo, or Indigofera micheliana or guatemalensis, was one of several genuses that yielded indigo, and during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries both Native American and African workers refined the plant into dyes in toxic obrajes de tinta or indigo workshops. Of the nearly eight hundred species of indigofera, I. tinctoria, I. suffruticosa, and I. micheliana or guatemalensis became the most prominent and sought after for commercial indigo production in the Americas.33

West African agriculturalists grew similar kinds of indigo. In addition to Lonchocarpus cyanescens, an indigo-bearing plant grown in southern Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and the Côte D’Ivoire, at least two species of Indigofera were cultivated in West Africa. Through indigenous agricultural development and ongoing trading relationships and interaction with North Africa and the Atlantic World, Indigofera tinctoria and Indigofera guatemalensis spread throughout West Africa.34 Experienced with different varieties of indigo, West Africans workers, though slaves, fostered its development in the British Caribbean. Yet their work experience with it changed in significant ways.

Figure 1. P. Lea, “A New Mapp of the Island of Jamaica” (1685). Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress.

To rationalize slave-based production, Jamaican indigo planters recorded cultivation techniques, employed accounting methods, and introduced technologies that on the one hand facilitated the development of economies of scale and on the other imposed strict requirements and demands on labor. In West Africa during the slave trade era, indigo cultivation, processing, and dyeing were generally done within closely adjacent fields and workshops. The indigo produced in Jamaican forced labor camps was shipped across the Atlantic to English markets, where it fell into the hands of local dyers. Hence, most labor was devoted to the agricultural fields, which demanded meticulous cultivation. In fields allotted to indigo cultivation, the enslaved first weeded the land and then, usually in March, tilled “small trenches of two or three inches in depth, and twelve or fourteen inches asunder; in the bottom of which the seeds are strewed by hand, and covered lightly with mould.” Indigo required constant weeding and, in Jamaica, yielded from two to four cuttings. By the mid∇eighteenth century, planters figured to make twelve to fifteen pounds of indigo annually per worker, and later in the century they calculated that on average four indigo workers could cultivate five acres of indigo land as well as produce their own food provisions.35 This, to the planter class, was the ideal output from their slave labor force.

Organizing the development of indigo works to produce the dye on a large scale, colonial planters introduced technologies that demanded that some slaves adapt to different kinds of work. In their combining of large-scale agricultural production and refinement, indigo and sugar production resembled each other. In fact, while most indigo plantations specialized in the crop, others, such as the Lucky Valley and 7 plantations, produced indigo along with sugar, corn, and ginger and depended on slaves not only to cultivate the fields but also, with white artisans, to work as carpenters.36 These craft workers were needed to build indigo vats, a central feature of indigo production in the Caribbean by the 1660s (see figure 2). In the early seventeenth century, Dutch and English merchants learned indigo production techniques in India, where specialists made the dye by “steeping the plant and agitating the liquid with ‘great staves.’ They skimmed off the clear water above the precipitate in stages, until the paste thickened enough to be spread out on cloths and partially dried in the sun.”37 By the second half of the century, colonists transferred these technologies to the Caribbean.

Figure 2. From Jean Baptiste du Tertre, Histoire générale des Antilless habitées par les François, vol. 2 (Paris, 1667∇71). Indigo production in the French Caribbean. John Carter Brown Library, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

Within this wider context of movement and trade, Jamaicans integrated knowledge from global sources. Indigo went through a series of vats to be transformed into an exportable dyestuff. After the crop was cultivated and harvested, it was

steept in proportionable Fats 24 Hours, then it must be cleared from the first Water, and put into proper cisterns; when it has been carefully beaten, it is permitted to settle about 18 Hours. In these Cisterns are Several Taps, which let the clear Water run out, and the thick is put into Linnen Bags of about three Foot long and half a Foot wide, made commonly of Ozenbrigs, which being hung up all the liquid Part drips away. When it will drip no longer, it is put into Wooden Boxes three Foot long, 14 inches wide, and one and a half deep. These boxes must be placed in the Sun till it grows too hot, and then taken in till the extreme Heat is over.38

The production of indigo, as illustrated in Jean Baptiste du Tertre’s study of the seventeenth-century Caribbean, also required workers to pound the indigo leaves in mortars with pestles before they were steeped.39 Synthesizing several fields of knowledge, including African agricultural knowledge and woodworking skills and South Asian indigo-processing technology, Jamaican indigo plantations supplied Great Britain’s growing demand.

Though indigo became a profitable enterprise for many, planters also faced risks, and some lost their investments. The plant was subject to infestation and, like other plants, could fail because of unexpected, inadequate, or excessive rainfall. In some cases, perhaps as a result of sabotage by slaves, the indigo could spoil because it was steeped for too long. In other cases, the water was agitated too much or drawn off prematurely. Furthermore, the scale of production created clear hazards for the slave labor force. Even Bryan Edwards, the staunch defender of the institution of slavery, acknowledged “the high mortality of the negroes from the vapour of the fermented liquor (an alarming circumstance, that, as I am informed both by the French and English planters, constantly attends the process).”40

Through the knowledge they brought to the Americas and in spite of the toll that slavery in the Americas took on their bodies, African workers placed their imprint on the indigo exported from Jamaica. The African labor force, many coming with indigo cultivation and processing skills, made adjustments to their new environment and indigo production technology. In Barbados during the mid∇seventeenth century, Africans used indigo-processing technology that they brought from West Africa. However, by the late seventeenth century the planter class elsewhere in the English Caribbean introduced new technologies that allowed for large-scale indigo manufacture, such as working with larger vats, hanging the indigo to dry in the sun in burlap sacks, and dividing the final product into standard-sized blocks for export. Slaves from Africa who processed the dye had to adapt to these newer techniques.41 However, Africans’ woodcarving skills, experience in indigo cultivation, and other kinds of indigo production knowledge sped up the development of indigo production in the Caribbean.

When the British expanded into the Carolinas, they established linkages with the Caribbean that provided not only models but also capital and labor for the development of indigo on the mainland. For instance, in September 1670, Captain Nathaniel Sayle, son of Carolina’s governor, brought to the colony on his ship the Three Brothers three white servants and a black family of three, individually named John Sr., Elizabeth, and John Jr. Similarly, other colonists were called upon to “tranceport themselves sarvants negroes or utensils the Lords proprietors of the province of Carrolina.”42

Hoping to begin indigo production on the mainland, English colonists went through Barbados for instructions and seeds before setting sail for Carolina. Around 1670, the ship captain Joseph West had instructions to stop in Barbados to procure “Cotton seed, Indigo seed, [and] Ginger Roots” to take to Carolina to begin a plantation using contracted Irish workers. This first attempt ended in failure because they missed the planting season. West reported in 1670 that their crops were “blasted in October before they could come to perfection.” Despite this loss, many remained confident that plantation agriculture would take root in Carolina.43

Persistent colonial efforts, mobilizing African and European labor, brought small-scale successes that accumulated over time and slowly extended indigo culture into Carolina. Shortly after the colonial project began, the trader Maurice Mathews found that “Cotton growes freely. … Indigo for ye quantity (by the approbation of our western planters I speake it) I haue as good as need be.” Colonial Secretary Joseph Dalton indicated that “as for Indicoe wee can assure ourselves of two if not three Cropps or cuttings a yeare, and as the Barbados Planters doe affirme it is as likely as any they have seen in Barbados.”44 Indigo production continued into the late seventeenth century, but it tailed off by the second decade of the following century. By 1710, Carolina imported an increasing number of African workers while exporting, according to one contemporary observer, “about seventy Thousand Deer-skins a Year, some Furs, Rosin, Pitch, Tar, Raw Silk, Rice, and formerly Indigo.”45

With the interaction between people on the mainland and the islands continuing well into the eighteenth century, the mixed slave and indentured labor force gave way to one that was primarily African, and rice became the colony’s staple crop. However, immigrants in early eighteenth-century Carolina looked to profit from the indigo industry, as illustrated in contemporary reports and publications about the agricultural prospects of the colony. For example, Peter Purry’s 1731 advice manual hoped to lure prospective Swiss immigrants to come to Carolina and raise “Vines, Wheat, Barley, Oats, Pease, Beans, Hemp, Flax, Cotton, Tobacco, Indico, Olives, Orange trees and Citron trees.”46

The Lucas family of Antigua entered South Carolina within this larger context of Atlantic commerce and colonial expansion. When the family established itself in South Carolina, it built upon precedents both there and in the West Indies. Aware of indigo development in the Caribbean, including her native Antigua, which exported indigo in the early eighteenth century, Eliza Lucas wrote her father for indigo seeds from the island, which he sent to her. In July 1740 she told her father about the “pains I had taken to bring Indigo … to perfection, and had great hopes from the Indigo (if I could have the seed earlier next year from the West India’s) than any of the rest of the things I had try’d.” The following year, after a frost destroyed most of the indigo crop, she wrote, “I make no doubt Indigo will prove a very valuable Commodity in time if we could have the seed from the west Indias [in time] enough to plant the latter end of March, that the seed might be dry enough to gather before our frost.”47

Lucas did not depend only on indigo seeds from the Caribbean; she also looked to the islands for skilled craft workers to make indigo vats. In 1741, her father sent a worker to construct these vats and to oversee the process of indigo manufacture. The estate first employed Patrick Cromwell and then his brother Nicholas, both from the island of Montserrat, but Eliza dismissed them both, suspecting that they had sabotaged the operation out of a fear that she and possibly other Carolinians would compete with their home island. In response, Governor Lucas of Antigua looked elsewhere in the Caribbean for skilled labor.48 In particular, he turned to the French West Indies for workers experienced in indigo. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a heavily African workforce produced indigo in the French islands of Saint Domingue, Guadeloupe, and Martinique. Often working on small plantations of from ten to twelve workers, they mastered the different stages of production, including cultivation, building of vats, and reduction of the plant to dye.49 Certainly aware of the French Caribbean model and hoping to establish indigo manufacturing on his Carolina estates, Governor Lucas “sent out a negro from one of the French islands” to supervise the process. Soon after, the Lucas estate added indigo to its exports of rice, pitch, salt pork, and tar.50

While mobilizing Afro-Caribbean labor, the Lucas estate received other inputs of labor from West Africa. A 1745 inventory of slaves on the Garden Hill property, a site of indigo production beginning in 1744, listed thirty-five men, sixteen women, seventeen boys, and eleven girls, including workers named Quamina, Quashee, Quau, Quaicu (appearing twice), and Cuffee. Their names indicate origins from the Gold Coast of West Africa, its interior, or its periphery, where indigo-dyed textiles were produced along with a range of other agricultural and craft goods. A number of areas produced cotton textiles, including the states of Bono and Akwapem and the town of Begho and its hinterland. Swept through in the first half of the eighteenth century by Asante armies, who in turn sold the captives to European slave traders, these areas supplied Carolina with slave labor. With workers from the Caribbean and West Africa who brought expertise in indigo production to the colony, the Lucas estate created a template for others to follow.51

Building upon the Caribbean model, the Lucas estate provided an example to South Carolina planters who sought to move into indigo production. This became particularly significant because the War of Jenkins’ Ear (1739∇41) between England and Spain blocked international trade routes. As a result, Carolina planters looked for economic alternatives and, like previous generations, turned to indigo production. By midcentury, indigo was South Carolina’s second largest export, with 87,415 pounds being shipped from Charleston between November 1749 and November 1750.52 Lucas listened to the needs of the colony, but for the actual labor Carolinian planters depended upon knowledge from the larger Atlantic World.

Throughout this period, Carolina’s indigo plantations drew heavily upon the slave trade from West Africa for their labor force. Estimates of the labor required to cultivate indigo allow a rough indication of the number of Africans engaged in its production in mid-eighteenth-century Carolina. The 1761 pamphlet A Description of South Carolina: Containing Many Curious and Interesting Particulars Relating to the Civil, Natural and Commercial History of that Colony estimated the productivity of indigo workers. It reported that each slave cultivated approximately two acres of land per year, producing a total of sixty pounds of indigo while also cultivating food provisions.53 In 1750, South Carolina exported approximately eighty-seven thousand pounds of indigo. The crop yielded an estimated thirty pounds per acre, and one slave annually cultivated approximately two acres. Hence, one worker produced approximately sixty pounds of indigo per year. From the original group of African workers who helped give rise to indigo on the Lucas estate, indigo spread throughout the colony to involve at least 1,400 workers producing the over eighty-seven thousand pounds of indigo exported from Carolina at midcentury. Slaves produced this indigo while also cultivating enough food for everyone on their plantations.54

During the second half of the eighteenth century, indigo production expanded substantially, remaining Carolina’s second-most important export. Much as tobacco shaped the culture of colonial Virginia, indigo along with rice helped to define the character of South Carolina’s planter class, fields, and slave quarters. Among elite white Carolinians, indigo culture in South Carolina spread through an established network that connected colonial plantations with each other and the wider Atlantic commercial system. Through the slave trade, the migration of free labor, trading partnerships, published works, private correspondence, colonial newspapers, and commercial documents, Carolinian elites participated in a global flow of labor and knowledge that stimulated the development of indigo in Carolina and supplied consumer demand across the Atlantic.55

Once indigo was established on the Lucas estate, information about how to cultivate and process the crop became more available to literate white Carolinians. Throughout the 1740s and beyond, South Carolina planters could thumb through the pages of the South Carolina Gazette and other publications for advice and instructions on how to raise indigo. For instance, Charles Pinckney, who married Eliza Lucas in May of 1744, wrote a series of Gazette articles to promote indigo. Writing under the pseudonym of “Agricola,” he reasoned that since rice prices were so low, Carolina planters should turn land and labor over to indigo. Quoting Philip Miller’s Gardener’s Dictionary, which in turn drew upon the French missionary Jean Baptiste Labat’s account of indigo production in the French Caribbean island of Martinique, Pinckney detailed the characteristics of the indigo plant, reported the processing techniques, and envisioned the extraordinary prospects for indigo production in South Carolina. Other descriptions of indigo were published, and, though accounts differed in some details, by the 1750s information about indigo production was much more available to literate Carolinians. During the colonial period, the written descriptions of indigo then became a kind of currency that circulated among Carolina elites who hoped to capitalize on European demand for high-quality indigo and match the standard set by Guatemala.56 This intention was aided in 1757 when a group of planters established the Winyah Indigo Society in Georgetown. Modeled after the Charleston Library Society, it served as a clearinghouse for information on indigo and other matters, and it also established a school for indigent white children.57 Through these circuits, South Carolina set precedents for antebellum southern agricultural journals such as the Southern Agriculturalist, Edmund Ruffin’s Farmers’ Register, and De Bow’s Review. And in their private correspondence with each other, planters also passed on instructions about indigo production. For example, they advised each other on the best soils to grow the crop, which were in upland fields. In 1770, Peter Manigault told Daniel Blake, “It is a mistaken Notion that all good Corn Land is Likewise good Indigo Land, for Corn will grow in much wetter Land than Indigo, & the rich Knolls on your Land, which bear Corn extremely well, are too stiff & too low for Indigo.”58

South Carolina elites, with time freed up by the profits derived from slave labor, also produced forms of symbolic capital related to indigo that reflected and shaped white colonial identities and promoted the state to outsiders. This is particularly apparent from the cartouches on colonial South Carolina maps, which went through a number of changes. On the first cartouche, printed on a 1757 map by William de Brahm, are two statuesque black male figures removing water from an indigo vat and a third, who seems delighted about his work, dividing indigo into blocks for shipment (see figure 3). In comparison, a second cartouche, published on James Cook’s 1773 map of South Carolina, shows four primary characters: a black male figure loading a ship with indigo, two gentlemen overseeing the process, and a Native American male in the corner (see figure 4). Another is from a 1773 Henry Mouzon map (see figure 5). This cartouche emphasizes the technology and efficiency of indigo plantations, indicated by the ceaseless motion of the workers, the presence and cleanliness of their uniforms, and the proximity of indigo fields, vats, and sorting areas. This sense of order is heightened by the presence of white overseers, in contrast to the 1757 illustration, in which they are absent. These images did a number of things simultaneously—they revealed historical processes of material production, displayed clearly defined roles and expectations for black and white males in the colony, and concealed the role of enslaved women in the process of indigo production. In these cartouches, particularly Mouzon’s, the artists portrayed South Carolina as an essentially progressive society, a vision that stimulated the desire to introduce rice mills and other machinery into South Carolina after the Revolution. Furthermore, their imagery and placement on maps helped Carolina’s elite to legitimate their claims to both land and black labor.59

As planters discussed indigo in the pages of the Gazette, through their correspondence with each other and foreign merchants and commercial agents, and in the halls of the Charleston Library Society and the Winyah Indigo Society, they also talked about the need to import more slaves into the colony to do the work on their estates. Preferring slaves from the Senegambia region of West Africa, Carolina imported over seventy thousand slaves in the second half of the eighteenth century. When indigo took off in the colony, Henry Laurens and George Austin published an advertisement in the July 1751 South Carolina Gazette announcing the sale of “a cargo of healthy fine slaves” from the Gambia. Such slaves from the Senegambia region went directly to indigo plantations. Writing to Charles Gwynn in August of 1755, Laurens remarked, “The Indigo Planters whose Crops are good are just now at their wits end for more Slaves. Here is only one Gambia Man with us with 115, the Elizabeth.”60 Planters read in the pages of the South Carolina Gazette not only articles about indigo but also notices such as the advertisement on July 19, 1760, for “a choice Cargo of about Two Hundred very Likely and Healthy Negroes, Of the same Country as are usually brought from the River Gambia.” They saw the announcement on August 23 reporting “a fine and healthy Cargo of about One Hundred and Eighty Gambia Negroes, just arrived.”61 Or they came across the advertisement for the sale of “about Two Hundred very likely healthy NEGROES (of the same country as are usually brought from GAMBIA).”62 As South Carolina planters geared land to indigo, they had a labor force already accustomed to raising the crop.

Figure 3. William de Brahm, “A Map of South Carolina and a Part of Georgia” (1757). Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress.

Figure 4. James Cook, “A Map of the Province of South Carolina” (1773). Geography and Map Division Library of Congress.

Figure 5. Henry Mouzon Jr., “A Map of the Parish of St. Stephen in Craven County [South Carolina]: exhibiting a view of the several places practicable for making a navigable canal, between Santee and Cooper Rivers.” London: 1773. Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, Duke University.

Slaves engaged in every aspect of indigo production in South Carolina, from cultivating the crop in light, dry soils to constructing indigo steeping vats, extracting the dye, and making the barrels in which the indigo was shipped. And though planters had published accounts of indigo production available to them as a guide, their African labor force had practical knowledge either with indigo or in complementary trades such as wood-carving. While their experience shaped the outcome of indigo in Carolina, they also had to adapt their previous knowledge to different technologies or found that the skills they possessed were of more limited use. In particular, little dyeing was performed in Carolina, as indigo left Carolina packed in barrels exported across the Atlantic for English dyers.63

While African workers brought their experience with indigo to South Carolina, its forced labor system altered the relations of production. This was particularly the case in terms of the colony’s gender divisions of labor. In many parts of West Africa during the era of the slave trade, indigo production was controlled by women, who mastered cultivation, processing, and dyeing techniques.64 In the Americas women were generally excluded from processing and generally worked only in the fields. Yet their expertise was not lost upon planters such as Henry Laurens, whose slave Hagar developed the reputation for her “great care of Indigo in the mud.”65

In these ways, African workers both drew upon their previous knowledge in shaping South Carolina’s indigo plantations and adapted to different means of production and divisions of labor. In contrast to the planter class’s ideas and symbols about indigo, the slave community developed their own ideas about indigo, some of which were related to West or Central African cosmologies. Into the nineteenth century, the Gullah attributed spiritual significance to the color blue. Some Gullah householders painted their doors blue with residue from the indigo vats, and some Gullah conjurers gave their patients blue pills, apparently for protection from malevolent spirit beings.66

Though indigo was a steady source of wealth for South Carolina during the colonial period, its production went into decline in the late eighteenth century. With the growth of cotton textile production in Great Britain in the early nineteenth century, indigo production expanded in India, where between 1834 and 1847 four million people worked in this industry, coincidentally almost equal to the number of slaves in the United States in 1860. Through a combination of British policies and local practices, Indian peasants were forced to grow indigo rather than rice and fell into a cycle of debt that reduced them to virtual slavery, creating the conditions for the 1859 Bengal Rebellion. Indigo production endured into the twentieth century but was gradually replaced by the production of synthetic dyes in the Western industrialized nations. Meanwhile, in South Carolina during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, indigo production was replaced by cotton cultivation.67 Like rice, tobacco, and cotton production, indigo production would be no stranger to African workers in the early years of the Anglo-American colonial project.