4

Muscles of the Spine

Spinal Functions

The spine is the center of the body’s universe, from a mechanical point of view as well as an energetic one, since the main chakras also exist here. The spine is active in all asanas, even in a restful state like Savasana, where it acts as a conduit for subtle energies and messaging. The spine supports and balances the trunk and head in standing, sitting, kneeling, backbending, and arm-balance postures. It connects the upper and lower extremities and protects the spinal cord, which merges with the brain. Along with the articulating ribs, the thoracic spine houses the heart and lungs, and the lumbar/sacral areas protect sexual and other organs.

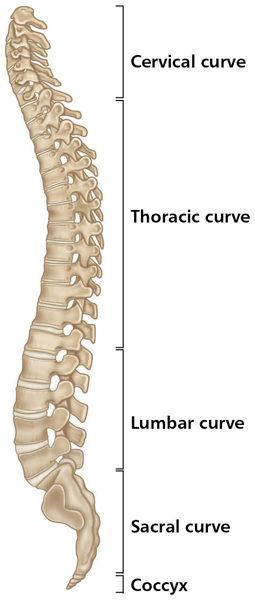

The muscles that work the spine stabilize and move its four different areas: cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral (minimal movement here). The fifth section, the coccyx, is immovable because its vertebrae are fused, but it does provide support and protection as weight is transferred while sitting. Thought of as the remnants of a tail in the evolutionary process, the coccyx maintains another purpose in the human body—that of attachment points of muscles and ligaments, mostly of the pelvic floor.

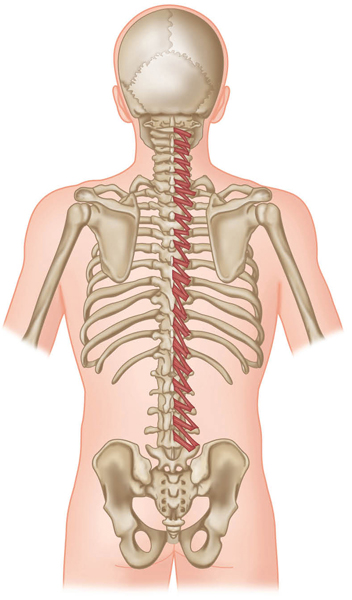

Spine, lateral view.

Spinal Actions

The top three mobile areas of the spine can do the actions of flexion, extension, lateral flexion to the right and left, and rotation to the right and left. The spine is also capable of hyperextension (backbending). There are, however, some limitations of spinal movements.

Cervical—Considered the most movable area of the spine as it curves anteriorly (lordotic) to balance the weight of the head, the top two vertebral joints are limited in some joint actions. The atlanto-occipital joint (between the skull and the C1 vertebra, called the “atlas”) can flex and extend (nodding the head), with very little lateral flexion and no rotation. The atlanto-axial joint (between C1, atlas, and C2, axis) mostly rotates. All other cervical vertebral joints (C3–C7) are able to move freely in all three planes if there are no complications.

As in any yoga posture, a main goal is to create space in the body, not condense it; that is why I instruct a student to extend, not hyperextend, the posterior neck position and to not compress the vertebrae.

Atlanto-occipital joint.

Thoracic—This is the longest section of the spine, with twelve vertebrae. Its main limitation is hyperextension (arching the back, as in Ustrasana, camel pose, see below). The posterior processes of the lower vertebrae in this region begin to slant downward, so when a backbend is performed, one bony process may come in contact with the next. This is very important for yoga practitioners to understand: as the back arches, it cannot be forced into a bone-against-bone position.

Each person is different, but most have a natural kyphotic curve in this section (posterior) and a backbend creates the opposite. Backbends are aided more by the lordotic areas of the spine (the lumbar and cervical areas), as well as by the upper part of the thoracic region, where bony limitation is not as severe. Care and correct explanations must be provided to engage the proper muscles for support of these regions and allow openness of the front of the body.

The change in angle between the facet joints lends itself to the movements that are possible at each section of the vertebrae.

Feeling length in the spine as the back bridges will help one perform with more ease and also protect the discs of the spine (cartilage between the vertebrae).

Ustrasana (Camel Pose) Level I-II: anterior muscles pictured are stretching, as posterior muscles located along the spine support the back-bending. Notice the position of the pelvis (in line with the knees) and the cervical area of the spine supporting, not dropping, the weight of the head.

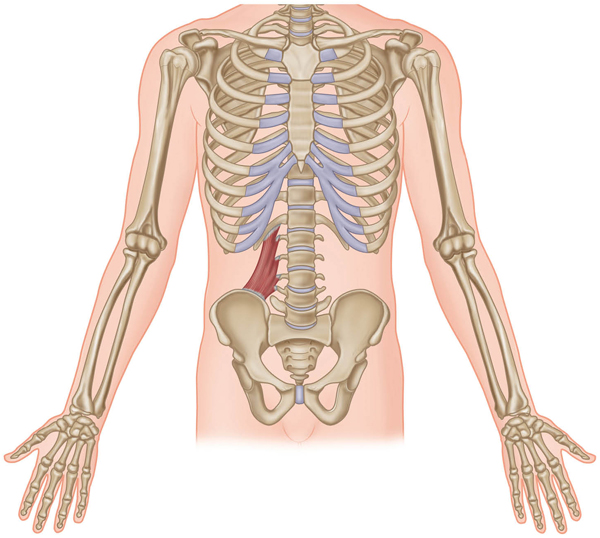

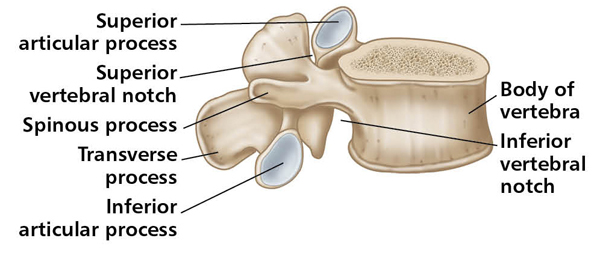

Lumbar—This section of the spine has an anterior curve and contains the five largest and thickest spinal vertebrae. The main limitation is rotation, because of the shape of the bones. The spinal (posterior) processes are bulky, and the facets (articulating surfaces) are orientated in such a way as to limit turning. Once again, this knowledge is of the utmost importance, especially when a spinal twist is performed.

Many injuries of the lower back in yoga can happen because a twist is forced more through the lumbar spine than through the thoracic spine. Overstretching in spinal flexion is also a risk factor.

Lumbar vertebra (L3) lateral view.

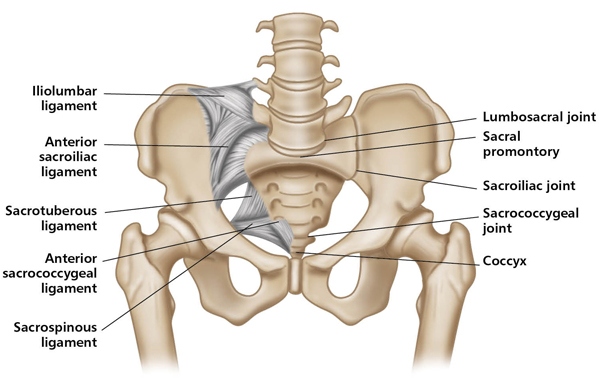

Sacral—By the end of puberty, four to five vertebrae in this part of the spine have fused together, causing the formation of the sacrum bone, which solidifies through the years and bears the weight of the spinal column. The vertebrae themselves do not move, but at the junction of the sacrum with the pelvis (the sacroiliac, or SI, joint) there is a gliding motion. This is subtle and involuntary; it happens naturally in childbirth as ligaments supporting the joint begin to stretch when the hormone relaxin is released.

Extreme overstretching in yoga (as in Sitting Forward Bend, Paschimottanasana) can lead to SI joint discomfort, as ligaments cannot easily “bounce back” to their original length. The area becomes less stable, with resulting inflammation and pain. Sitting too much can also irritate this region.

Actions specific to this pelvic area are called “nutation” (forward motion of sacrum base) and “counter-nutation” (backward motion of sacrum base). They should not be confused with pelvic rotation or tilt, although they can happen along with these actions.

In conclusion, the sacral area of the spine, although not very movable, can be irritated. This is seen in more advanced yoga postures, and one should take care in intense forward-bending poses, twists, wide-leg straddles, and even backbends.

Ligaments around the pelvis and the sacroiliac joint.

Prasarita Padottanasana (Wide-leg Forward Bend) Level I

The following sections present the major muscles working the spine, with related asanas illustrated and explained in detail.

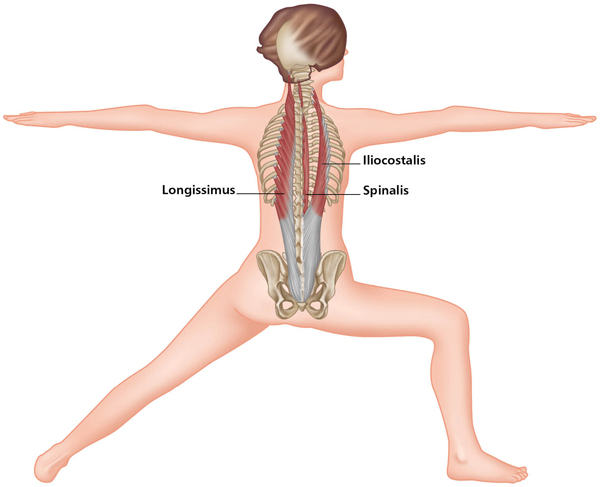

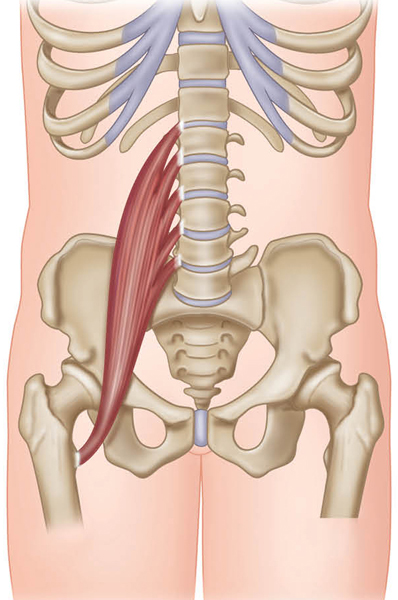

ERECTOR SPINAE (SACROSPINALIS)

Virabhadrasana II (Warrior II) Level I

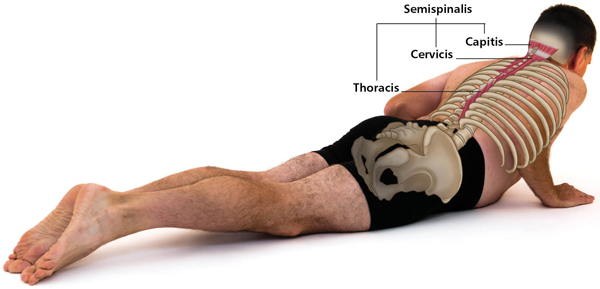

SEMISPINALIS CAPITIS, CERVICIS, THORACIS

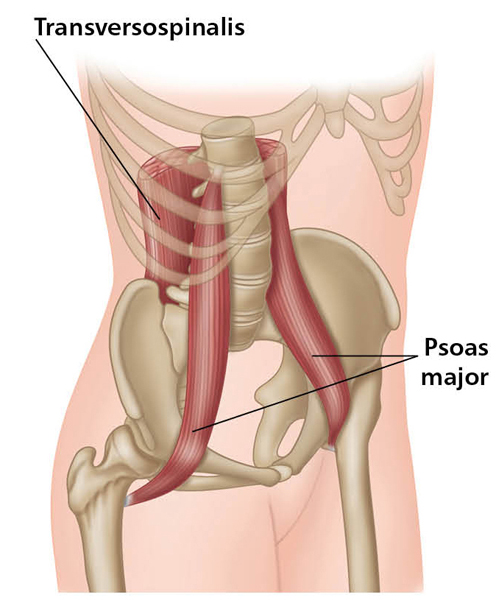

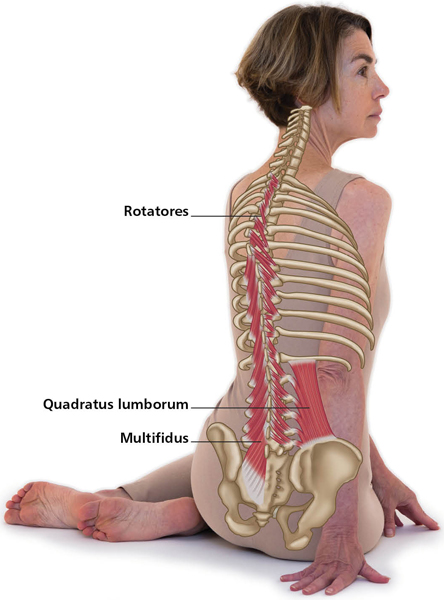

Transversospinalis (meaning “across the spine”) is a composite of three small muscle groups situated deep to erector spinae. However, unlike erector spinae, each group lies successively deeper below the surface, rather than side by side. From the most superficial to the deepest, the muscle groups are semispinalis, multifidus, and rotatores. Their fibers generally extend upward and medially from the transverse processes to the higher spinous processes and are sometimes grouped as the “deep posterior muscles.” The combined actions are mostly rotation and extension, with some lateral flexion.

Bharadvajasana (Seated Twist) Level I

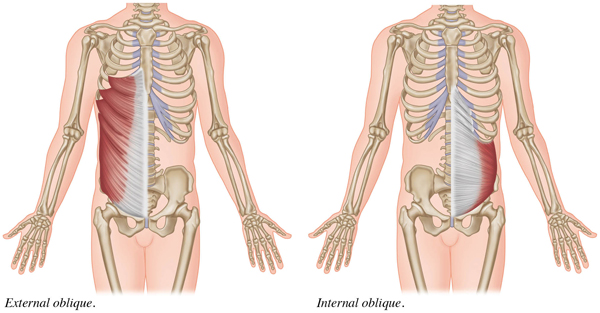

EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL OBLIQUES

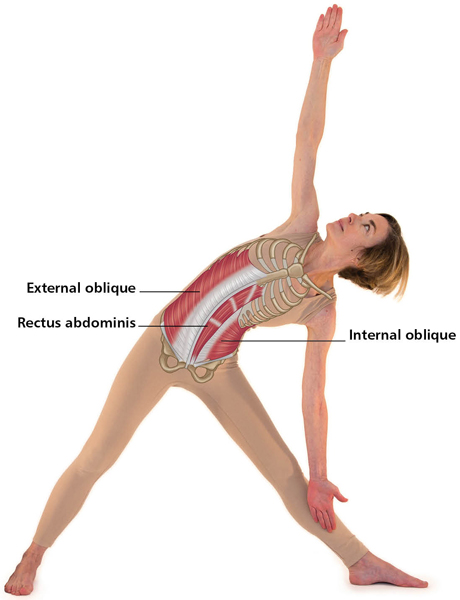

Trikonasana (Triangle Pose) Level I

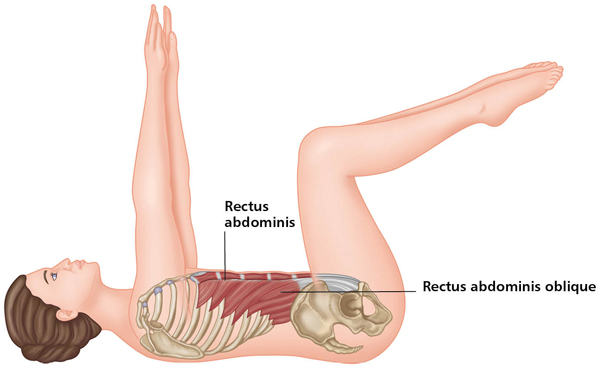

Apanasana (Wind Reliever) Level I

Viparita Virabhadrasana (Reverse Warrior) Level I

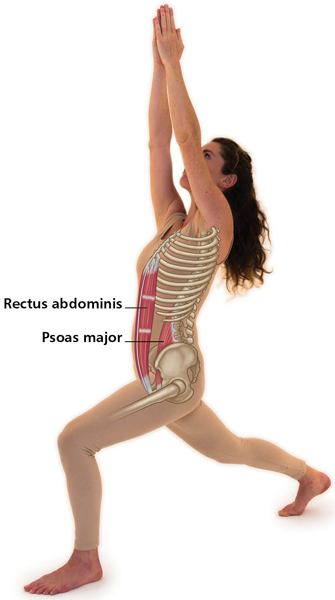

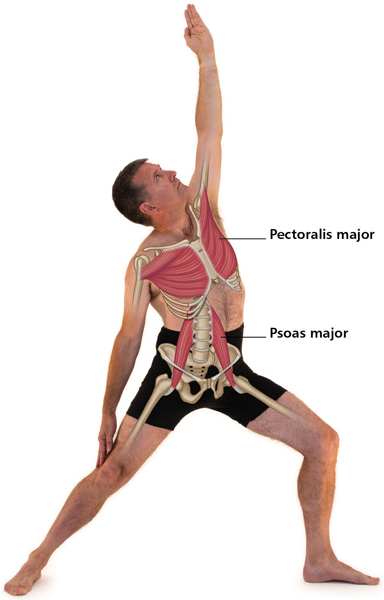

Alanasana (High Lunge or High Crescent Moon) Level I, II