5

The Deep Core and Pelvic Floor

In Chapter 4 the spine was discussed as the center of the body’s universe. The connection of the spine to the pelvis through the sacrum adds the central basin, and the two together become our center of gravity, or core.

The Superficial Versus Deep Core

The surface core is the focus of many exercise programs. The muscles targeted are usually the anterior abdominal muscle group, including three of the four abdominal muscles—the rectus abdominis, and the external and internal obliques. These muscles mostly flex and rotate the thoracic/lumbar spine (Chapter 4).

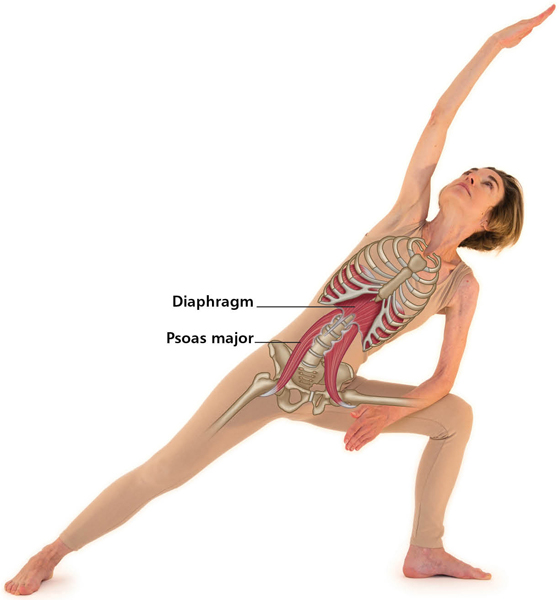

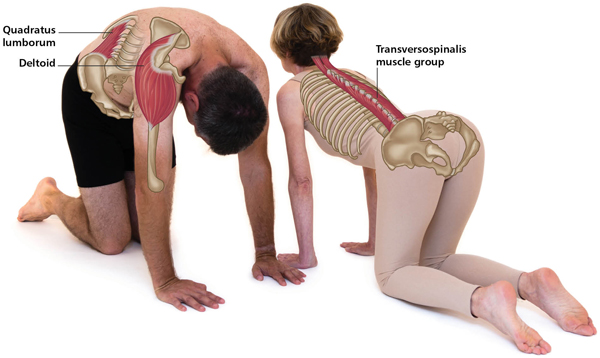

One must go deeper in order to address the support and health of the entire center of the body. This is where balance, strength, and stability integrate through muscle connection around the lumbar spine. Five hidden yet very important muscles are the diaphragm (lower attachments L1–L3, page 32), psoas major (page 69), quadratus lumborum (page 63), transversalis group (page 57, minus the semispinalis), and transversus abdominis (page 35, the fourth abdominal muscle). These muscles have already been pictured in the respiration and spine chapters, as they are relevant to and located in these areas. Putting them together helps one see the relationship to the deeper layer of the lower spine and pelvis, the area called the “deep core,” where stabilization of the lumbar spine to the pelvis occurs and is necessary for proper alignment of the body.

Asanas That Heavily Use the Deep Core Muscles

All asanas can incorporate the deep core, with special cueing to help the practitioner (see sections on cueing in Appendix 2). Some postures are more useful than others in addressing this area. Starting with breath work will help bring attention to the deep core, and postures of balance and strength can be valuable in discovering the significance of these concealed muscles.

Chakravakasana (Cat/Cow Stretch or Sunbird) Level I

The Pelvic Floor: Where the Physical Meets the Spiritual

The pelvis is a basin, acting as an architectural keystone to support and balance the two femurs on either side. It is made up of three bones: the sacrum and two iliac bones (fusion of the ilium, ischium, and pubis areas to create the iliac bones happens by or during puberty).

The pelvis can move through space, but the action really occurs at the lumbar spine and iliofemoral (hip) joints, such as in pelvic tilting. Cat and Dog/Cow positions incorporate forward and backward tilt of the pelvis and can be a part of other asanas when cued.

The bottom of this area, the pelvic floor, is unique and especially important in yoga. The many facets and structures are worth investigating, as they enhance breath, posture, balance, and vitality.

Understanding this area and its use is complicated but necessary in most yoga practices. There is another diaphragm here, the pelvic diaphragm, which includes layers of muscle and fascia, as well as the sacral nerve plexus. It is somewhat coordinated with yet a third diaphragm located in the throat, the vocal diaphragm, when breathing. Suffice it to say the pelvic area is most interesting to yogis because of muscular support, sensitive nerve endings, and breath work.

In yoga, we “lift” the pelvic floor. This is a bit ambiguous, but the image of pulling up the bottom of the pelvis aids in engaging the correct musculature, whether in sitting, kneeling, standing, and even inverted postures. This action increases support, balance, and strength of particularly small but necessary muscles. These muscles include the levator ani and coccygeus and other muscles that, when engaged, can strengthen the pelvic floor. The lower abdominal wall is also involved, as well as the psoas major, as a stabilizer. Even the hip adductors can be targeted to help lift the pelvic floor.

The perineum is an area between the inner thighs, in between the urethra and the anus, with the pelvic diaphragm as its roof. It all forms a diamond shape, with two triangles intersected by an imaginary line between the sit bones—the urogenital and anal triangles. Sphincter muscles (ani and urethral) are located here (sphincters are circular muscles that control the flow of material). This is also the location of the engagement of the first bandha, or lock, which is meant to raise subtle energy fields to a higher level (see “Bandhas” section below).

When practicing or teaching yoga, a distinction must be made between engaging the pelvic floor and activating the bandhas. When using the pelvic floor to support postures, there is a small, intentional contraction of muscles to lift upward. To activate the bandhas, controlled breathing, along with contraction done in a binding (or held) fashion, is ultimately performed to attain detachment from external senses and release energy up through the spine.

Yoga Philosophy: Bandhas, Nadis, Chakras, and Limbs

Bandhas

There are four major bandhas incorporated in yogic styles: mula bandha (perineum and anus), uddiyana bandha (abdomen), jalandhara bandha (throat), and jivha bandha (tongue and palate). Breath work incorporated into Kundalini Yoga is a good example of using all four when appropriately cued. The two lower ones are discussed here, as they relate to the pelvic area.

Mula bandha is the lock associated with the pelvic floor, specifically the perineum and anus. This is a neuromuscular junction that is stimulated by focused concentration and contraction of the area (similar action is present in all four bandhas). This is voluntary and deliberate, where a sensation can be felt as energy is tapped, and a contraction is held to engage an impulse that would release upward through the spine.

Uddiyana bandha is a good example of “flying upward,” the literal definition of the Sanskrit term. The low, mid-abdomen, diaphragm, and ribs are focused areas where there is an ascending movement of the diaphragm while the abdominals are concave. It is mentioned here because of the interaction of the pelvic floor muscles with both mula bandha and uddiyana bandha. Study of these is best done with a master, with the most important aim being a progressive feeling arising out of sustained contraction and not thinking about what is being activated muscularly.

Bandha work becomes part of a sustained practice of yoga asanas and pranayamas. Its goal is the higher aspects of the spiritual path, where the chakras and nadis are important. Awareness becomes internal more than external, allowing for deeper meditation, where enlightenment, known as Samadhi (the eighth limb of yoga), can become a possibility.

Upavesasana (Sitting-down Pose) or Malasana (Garland Pose) Level I, II

Nadis

Nadis are channels of energy and motion that can be activated by Kundalini work, or “awakening”. As quoted by the Originator of this method in the USA, Yogi Bhajan (October 27th, 1988): “Kundalini Yoga is the science to unite the finite with Infinity, and it’s the art to experience Infinity in the finite.”

Nadis are also used in the practice of Eastern medicines, such as acupuncture, and in the use of meridians. They connect at the subtle energy points known as the “chakras.” Yoga and breath become a means of purifying these channels.

Sushumna, one of the three most important nadis, is the central channel through which life force flows (nadi means “stream”). A feeling is experienced as pranic energy passes upward, similar to that felt when engaging the bandhas. The other two important nadis are ida and pingala, the left and right channels along the spine.

Chakras

The Chakra System: The Cosmic Self

The cakras (Original spelling) come from an ancient tradition, the word appearing in India a few thousand years ago at the time of an invasion by Indo-European peoples (Aryans). This became known as the Vedic period, when a cultural mixing took place throughout India over the following centuries. The chakra was symbolically shown as a ring of light, with a historical meaning of “to bring in a new age.” Chakras are mentioned in the Vedas, the ancient Hindu text of knowledge.

Though a mystery from the past, we know the Sanskrit word chakra itself means “wheel,” as in the wheel of time, believed also to be a metaphor for the sun, therefore representing celestial balance. Yogic literature mentions the chakras as psychic centers of consciousness as early as 200 B.C. in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. The chakras as energy centers became an integral part of yoga philosophy through the Tantric tradition in the seventh century A.D., where integration of the many forces of the universe was emphasized. Yoga began to incorporate the whole being.

There are seven basic chakras (other minor ones are in the extremities) that work together as a complete system, sometimes called the “inner organs of the esoteric (obscure) body,” and which are found along the spine. They intersect with the nadis (spinal energy channels) as well as the endocrine system and nerve plexi. One could call the chakras “psychoenergetic” centers. They link to the natural elements of earth, water, fire, air, and ether, and their qualities help define human purpose. They are believed to receive, digest, distribute, and transmit life energy and are hence known as the “seven roots of awakening.”

The seven primary chakras are listed here, including the Sanskrit word for each. The sacred, ancient language of Sanskrit is revered as being designed for enlightenment, as are the chakras. The meaning and effects of the chakra system go way beyond what is indicated in this book—energy flow and auric fields are best described by other experts such as Barbara Brennan and Cyndi Dale. The text Yoga and Psychotherapy by Swami Rama is also useful and considered the authoritative work on Chakras.

1. Root Chakra—Muladhara

foundation; primal needs; grounding; connected; security

color: red; planet: Saturn; element: earth; sense: smell

location: above the anus, base of the spine, pelvic floor

governs feet, legs, large intestine, perineum

animal: elephant; root sound: lam

Kundalini Shakti coils here, power of the divine feminine

2. Sacral Chakra—Svadhisthana

womb; emotional/sex flow; sweetness; pleasure; creativity

color: orange; planet: Pluto/Moon; element: water; sense: taste

location: front face of lower spine, pelvis, sacrum

governs fertility, lower back and hips, bladder, kidneys, ovaries, testes

animal: crocodile; root sound: vam

expansion of one’s own individuality

3. Solar Plexus Chakra—Manipura

gut feelings; breath; warrior (courage); brilliant jewel; personal power

color: yellow; planet: Sun/Mars; element: fire; sense: sight

location: solar plexus, union of diaphragm, psoas, organs, centered around the navel

governs digestion, metabolism, emotions, universality of life, pancreas, adrenal glands

animal: ram; root sound: ram

influences the immune, nervous, and muscular systems

divine acceptance; love; relationships; passion; joy of life

color: green/pink; planet: Venus; element: air; sense: skin

location: upper chest, heart, lungs

governs upper back, psychic ability, some emotions, openness to life, thymus gland

animal: antelope; root sound: yam

engulfs the rhythm of the universe

5. Throat Chakra—Vishuddha

communication; self-expression; harmony; vibration; grace; dreams

color: sky blue; planet: Mercury/Jupiter; element: space; sense: hearing

location: throat, neck, ears, mouth

governs sound, power of voice, assimilation, thyroid and parathyroid glands

animal: white elephant; root sound: ham

communicates inner truth to the world, ascends physical to spiritual

6. Brow Chakra—Ajna

third eye; intuition; concentration; conscience; devotion; neutrality

color: indigo/purple; planet: Neptune; element: light; sense: the mind

location: center of head between and above eyebrows

governs creativity, imagination, understanding, rational dreaming, pineal gland

animal: black antelope; root sound: om

provides opportunity to see everything as sacred

7. Crown Chakra—Sahasrara

pure consciousness; spirituality; true wisdom; integration; bliss

color: white, also violet/gold; planet: Uranus/Ketu; beyond elements

location: top of the head, cerebral cortex

governs all functions of the body and mind, other chakras, pituitary gland

symbol: thousand-petaled lotus (void)

Kundalini energy (Shakti) unites with male energy (Shiva) to transcend into the essence of all

The Eight Limbs of Yoga

Throughout this text the limbs of yoga have been mentioned. They are listed here for reference, defined by Patanjali some 2500 years ago, as a guide for living the yogic way of life.

1. Yamas (restraints)

2. Niyamas (observances)

3. Asanas (postures)

4. Pranayama (mindful breathing)

5. Pratyahara (turning inward)

6. Dharana (concentration)

7. Dhyana (meditation)

8. Samadhi (bliss)

In this anatomical and movement text we are concerned mostly with the asanas (3) and pranayama (4), developing physical balance and breath through awareness.

Yoga is not a linear method. Practice is begun on the mat, learning techniques from different teachers. The complete teachings of yoga philosophy are discovered as one continues to delve into the essence of yoga as it is incorporated into daily life.

All things are connected.

Anjaneyasana (Crescent Pose; Low Lunge) Level I