6

Muscles of the Shoulder and Upper Arm

This complex area is simplified by breaking it down into the following joint areas:

• The shoulder girdle—the sternoclavicular joint

• The shoulder joint—the glenohumeral joint

• The elbow joint—the humeroulnar joint

Each joint area has its own specific actions, and a few muscles share attachments across two or more different joints. These muscles are known as “multiarticulate” because they work more than one joint.

The structure of the shoulder permits a wide range of motion, allowing considerable freedom in the positioning of the arm and the hand. Movements of the shoulder region are determined by muscles located on the chest, back, and upper arms. The brachial plexus nerve center passes through here and down the arm, innervating many of the muscles of the entire arm.

Shoulder Girdle

Structure

This is a separate area that allows the shoulder joint to achieve an excellent range of motion of the arm. Three bones articulate in two different areas to form the shoulder girdle: the clavicle, scapula, and sternum. Movements of the shoulder girdle are activated mostly at the sternoclavicular joint, which in turn moves the scapula. This joint is the only point where the axial skeleton connects to the trunk. The lesser joints are the scapulothoracic, acromioclavicular, and coracoclavicular, where bones articulate but not much movement happens.

Actions

There are six to eight actions of the shoulder girdle joint, depending on which text is referred to. For the purposes of this book all movements are listed, as they are major actions associated with many yoga postures. They are elevation, depression, abduction (protraction) and adduction (retraction), upward and downward rotation, and forward and backward tilt. The actions are indicated by how the scapula moves in space: the scapula moving up is elevation, down is depression, away from the spine is abduction, and toward the spine adduction. Upward rotation is accomplished by the scapula’s inferior angle moving out and up; downward rotation is the return from this position. Forward tilt is best seen when the arm is extended behind the body, and backward tilt can happen in a backbend, where the superior scapula tips posteriorly. Chapter 1 illustrates some of these actions.

Almost all yoga asanas incorporate shoulder girdle movement. Even in Tadasana (Mountain Pose) and sitting meditation, one is reminded to “slide the shoulder blades down the back.” This is a subtle combination of the actions of adduction, downward rotation, and depression.

Muscles

The six muscles working the girdle are the pectoralis minor, serratus anterior, subclavius, levator scapula, rhomboids, and trapezius. All six are located on the chest (anterior) or upper back (posterior). Two of them, the levator scapula and the upper trapezius, are biarticulate with the cervical spine. Each muscle is very specific, especially the trapezius, as its different parts can do opposite actions, a rare occurrence in muscles.

Makarasana (Crocodile Pose) Level I

Adho Mukha Svanasana (Down Dog) Level I

Ardha Purvottanasana (Reverse Table or Half Upward Plank Pose) Level I

Shoulder Joint

Structure

The main shoulder joint is the glenohumeral joint, specifically the articulation between the scapula and the humerus. A multiaxial ball-and-socket joint, the structure comprises the glenoid cavity (socket) of the scapula, in which the head of the humerus (ball) sits. This cavity, or fossa, is shallow compared with other ball-and-socket joints, thus allowing greater range of motion, but less stability. The shoulder joint is complicated and multifaceted.

Connective Tissue

The head of the humerus is large in relation to the cavity it fits into. To achieve a tighter fit there is a fibro-cartilaginous ring called the “glenoid labrum” that helps seal the humerus in place more snugly. The shoulder joint capsule is also strengthened by means of the ligamentum semicirculare humeri, a ligamentous tissue that lies in close relationship with the tendons of the rotator cuff to bring integrity to the area.

Because the shoulder joint articulation is not deep and gravity acts as a force on the humerus, the ligaments of the joint must be very strong and intact to help hold the joint together. Three glenohumeral ligaments in the front of the joint and an inferior and superior coracohumeral ligament (running from the coracoid to the humerus) are the main reinforcing structures.

Actions

The upper arm (humerus) is the visual indicator when deciphering what action is happening (e.g., the upper arm in front of the body indicates flexion of the shoulder joint). The main actions are the true ball-and-socket joint actions of flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, and internal (medial) and external (lateral) rotation. Because the joint is so mobile (thanks to the aid of the shoulder girdle joint area), the joint can also hyperflex, hyperextend, hyperabduct, and hyperadduct. Add another true joint action of moving the humerus from the frontal to the sagittal plane and back again, and horizontal adduction/abduction is included. Diagonal movements are the combination of some of these actions. (Note: the action of horizontal adduction is sometimes called “horizontal flexion”; the action of horizontal abduction is also referred to as “horizontal extension”—see Chapter 1 for illustrations.)

Glenohumeral joint.

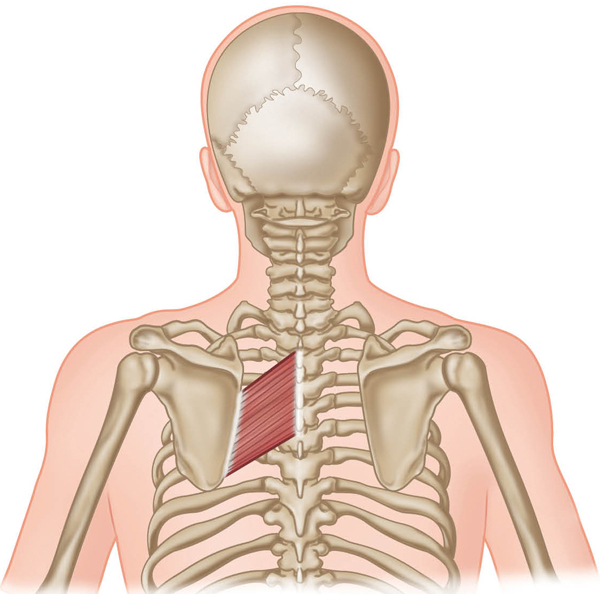

Muscles that cross the shoulder joint (posterior view).

Muscles

Muscles that move the upper arm have to cross the glenohumeral joint in order to work it. This is a major principle of kinesiology: if a muscle does not attach and then cross from one of the articulated bones to the other in some way, how can the bones be moved when the muscle is contracted?

Example: The infraspinatus muscle (see page 103) crosses the shoulder joint from the scapula to the humerus to work it. As it contracts concentrically (shortens), the arm is pulled backward and can rotate externally.

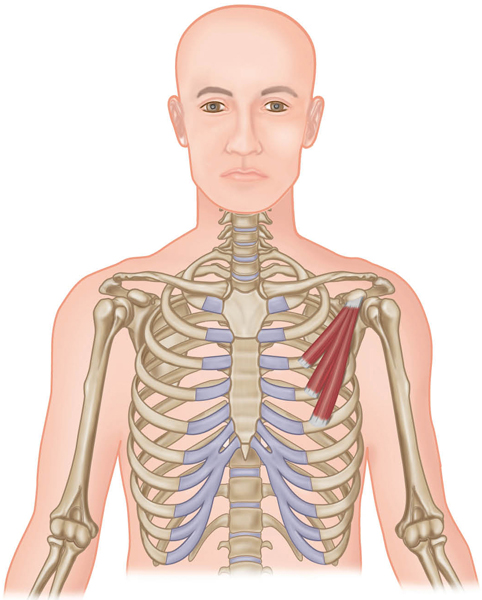

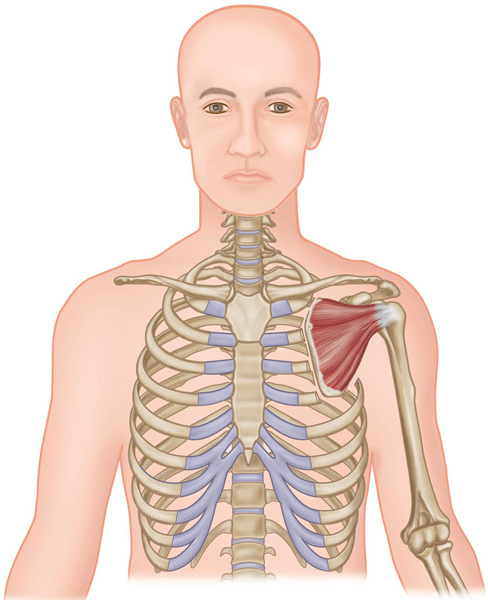

Viewed anteriorly, the muscles that cross the shoulder joint are the pectoralis major, anterior deltoid, coracobrachialis, and biceps brachii. The posterior muscles are the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres major and minor, latissimus dorsi, posterior deltoid, and triceps brachii. The subscapularis rounds out the shoulder joint’s 11 muscles (counting all deltoids as one muscle). Hidden behind the rib cage and on the anterior side of the scapula, the subscapularis is one of the four rotator cuff muscles of the shoulder joint (the “SITS muscles”: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis).

To make things simpler, most of the time the anterior muscles do all forward movement, such as flexion, internal rotation, and horizontal adduction. Posterior-located muscles do the opposite actions of extension, external rotation, and horizontal abduction.

High Plank Pose to Chaturanga Dandasana (Four-Limbed Staff Pose) Level I, II

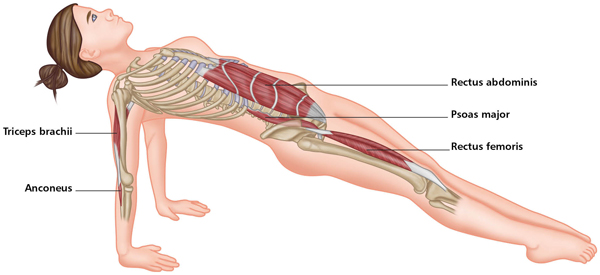

Urdhva Mukha Svanasana (Up Dog) Level I

Although most would not consider Uttanasana (see opposite) a deltoid-working pose, it does strengthen the anterior deltoid and stretch the posterior deltoid when the hands reach and press into the floor or a block. This asana is better known for its hip flexion movement as one hinges forward from the hip joint, as well as for using the hip and spinal extensor muscles, which contract to lift the torso back up. This is also discussed in Chapter 8.

Uttanasana (Forward Bend) Level I

Rotator Cuff

The rotator cuff is composed of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis, commonly known as the “SITS muscles.” The tendons of the “cuff” help hold the head of the humerus in contact with the glenoid cavity (fossa, socket) of the scapula during movements of the shoulder, thus helping to prevent dislocation of the joint. If dislocation occurs, the cuff is extremely compromised, overstretched, or possibly torn. Because the socket of the joint is shallow, the ligaments and tendons of the rotator cuff need to be strong enough to hold the humerus in place.

The following muscles will be demonstrated in one asana, Gomukasana, at the end of the section.

Note: The biceps brachii and triceps brachii are also shoulder joint muscles, but associated more with the elbow joint. They are discussed in depth in the next section.

Gomukhasana (Cow Face) Level II

Elbow Joint

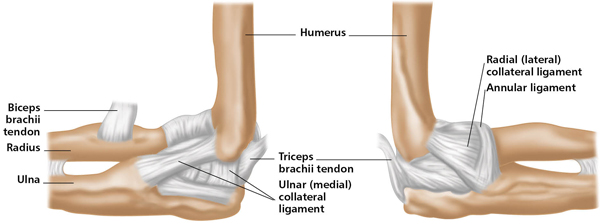

Structure

Technically called the “humeroulnar joint,” the elbow joint is composed of the humerus (upper arm bone), radius, and ulna. The last two are the forearm bones, with the ulna being the most medial (pinky side). At the distal end of the humerus are the trochlea and the capitulum, which together form part of the elbow joint with the radius and ulna.

Actions

The elbow joint is a classic hinge (ginglymus) joint, where only two actions are performed: flexion (bending) and extension (straightening). These actions can only happen in the sagittal plane (anatomical position). Some people are able to hyperextend, or go beyond extension; this is contraindicated in yoga postures of arm support and balance and should be monitored.

Ligaments

Ligaments and muscles work together to provide stability and mobility to the joint. The importance of this fact cannot be overestimated in yoga asanas, as all joints need to be strong, yet flexible: “ease in balance with effort.”

In the elbow, the ulnar (medial) collateral ligament consists of three strong bands (the anterior oblique, posterior oblique, and transverse oblique) that reinforce the medial side of the articular capsule. The radial (lateral) collateral ligament is a strong triangular ligament that reinforces the lateral side of the articular capsule. These ligaments connect the humerus to the ulna and act together to stabilize the elbow.

Muscles

Located on the upper and lower arm, with the proximal attachment above the joint, the main anterior muscles of the elbow are the biceps brachii, brachialis, and brachioradialis. The posterior muscles are the triceps brachii and the anconeus. The tendons of these muscles also act as stabilizers, crossing the elbow joint, and therefore provide extra security. It is easy to determine the action of the muscles: the flexors are anterior (anatomical position), and the extensors are posterior. Some of the extrinsic muscles in the forearm can also aid flexion, but since the contraction is weak, they will not be listed here.

The terminology helps in deciphering the names and types of some of the muscles: “bi” = two; “tri” = three. The biceps brachii therefore translates as “two heads” and “of the arm”; the triceps brachii means “three heads” and “of the arm.” As mentioned in the shoulder joint section, these two muscles cross both the elbow joint and the shoulder joint. The biceps brachii, however, is a triarticulate muscle, meaning that it acts across three joints—the proximal radioulnar joint (upper forearm), the elbow joint, and the shoulder joint.

On the following three pages you will find similarities between the main elbow flexors, and the asanas they are active in. The difference in the strength of their contraction appears when the forearm is either supinated or pronated in the movement (Chapter 7).

Bakasana (Crow or Crane Pose) Level II

Purvottanasana (Reverse or Upward Plank Pose) Level I

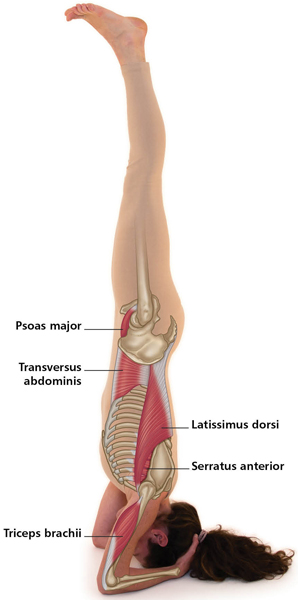

Sirsasana (Headstand) Level II

4 In any asana where the arm is raised, the shoulder girdle must also elevate to bring the arm past the horizontal to a vertical position. It is then its responsibility to do the reverse action, depression, to keep the shoulders down away from the ears.