9

Muscles of the Knee

The knee is a highly specialized design mechanism. It is supposedly the largest joint in the body, with the two long bones (femur and tibia) acting as levers. Where they meet there is good sagittal movement, but little lateral movement. This fact, plus the location of the knee between the hip and the foot, makes it vulnerable to injury. Yoga, with correct attention to postural alignment, can keep the knees healthy and strong.

Structure

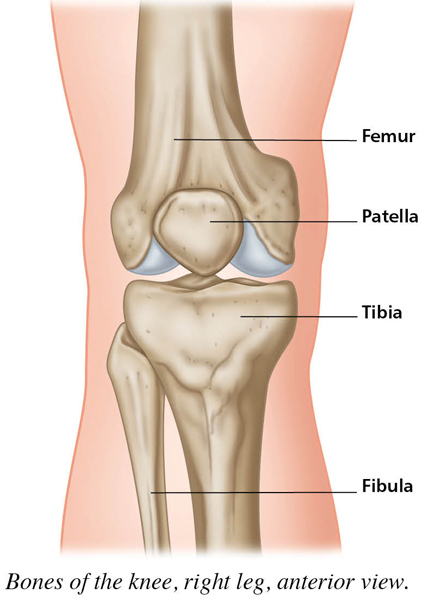

The femur (thigh bone) is the heaviest bone in the body. It articulates with the concave surface of the tibia to create the main composition of the knee. Add the patella (kneecap) as protection, and the fibula bone as an anchor for tendons and ligaments, and the structure becomes more efficient.

Bones of the knee, right leg, anterior view.

Connective Tissue

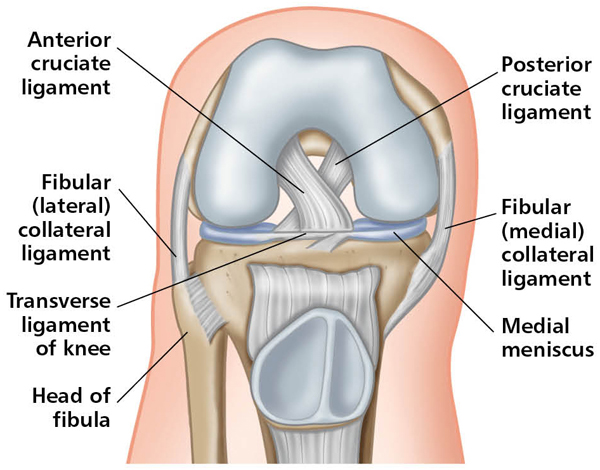

Because of the knee’s exposure, its ligaments and tendons must be in good working order to maintain integrity of the structure. On each side of the knee there is a collateral ligament: the tibial (medial) collateral ligament on the inside and the fibular (lateral) collateral ligament on the outside. The anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments cross inside the knee joint. Cartilage (the medial and lateral menisci) lies between the two main bones, with hyaline cartilage behind the patella for cushioning. The patellar ligament keeps the kneecap in place, joining with the quadriceps tendon to attach to the front of the tibia. There are bursae around the joint area to reduce friction.

Right leg (anterior view) with knee bent at ninety degrees.

Actions

The knee’s primary actions are flexion (knee bending) and extension (knee straightening). Little known but of great importance is its secondary action in the horizontal plane—inward and outward rotation. This can only happen when the knee is bent (flexed), and the action aids in correct tibial traction.

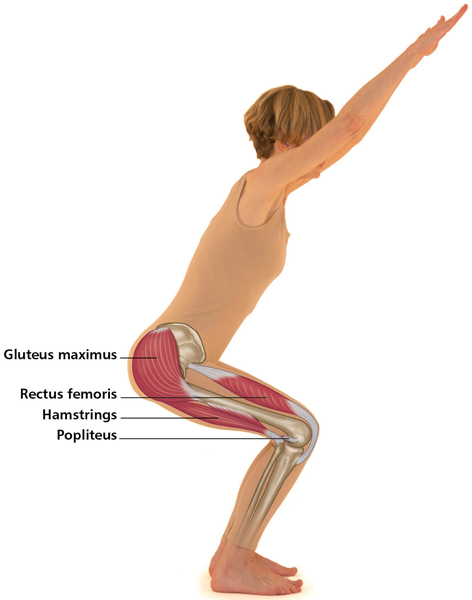

Muscles

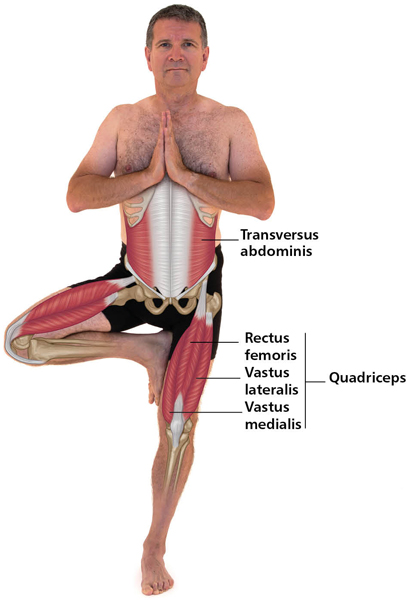

The quadriceps muscles, at the front of the upper leg, are the main extensors, and active in many movements—such as walking, running, jumping, and kicking—and in any movement that straightens the knee. These muscles form the most powerful and largest muscle group in the human body. They are stronger than their antagonists, the hamstrings. It is desirable to have the quadriceps at least 25% stronger than the hamstrings in order to balance the mechanisms of the knee joint.

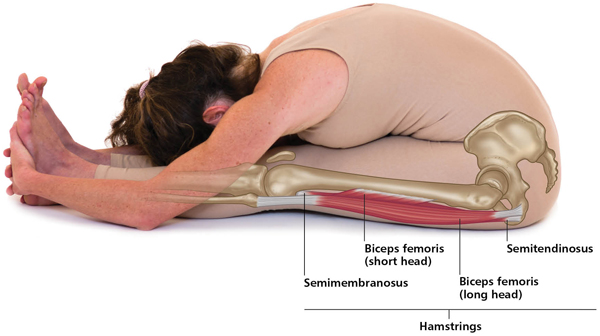

The hamstrings, at the back of the upper leg, are the main flexors, with other biarticulate muscles from the hip sharing the load (such as the sartorius and gracilis—see Chapter 8). The short popliteus is also posterior and invaluable in checking knee hyperextension.

Knee Flexors

Primary muscles: biceps femoris, semitendinosus, semimembranosus (see “Hamstrings,” Chapter 8).

Secondary muscles: sartorius, gracilis (see Chapter 8); gastrocnemius (see Chapter 10).

Knee Outward Rotators (Knee Flexed)

Biceps femoris (see “Hamstrings,” Chapter 8), vastus lateralis (see above, under “Quadriceps”).

For asanas, see Supta Virasana (Chapter 8, under “Hip Inward Rotators”). The thighs will rotate in, but the knees actually rotate out.

Knee Inward Rotators (Knee Flexed)

Semitendinosus, semimembranosus, sartorius, gracilis, vastus medialis (see Chapter 8, as well as under “Quadriceps” above).

There is actually no asana that is ideal for inward rotation of the knee. See Prasarita Padottanasana (Wide-leg Forward Bend, Chapter 4.) If the knees are flexed, the lower legs can rotate in. The muscles (listed above) that do this action can be worked in other ways, since most are biarticulate or can also do knee flexion or extension.

Natarajasana (Lord of the Dance Pose) Level I

Utkatasana (Chair Pose) Level I

Paschimottanasana (Sitting Forward Bend) Level I (Knee Flexor Stretch)