▲▲Hungarian Parliament (Országház)

Museum of Ethnography (Néprajzi Múzeum)

Between the Parliament and Town Center

▲Szabadság Tér (“Liberty Square”)

▲St. István’s Basilica (Szent István Bazilika)

▲▲Great Market Hall (Nagyvásárcsarnok)

ALONG THE SMALL BOULEVARD (KISKÖRÚT)

▲Hungarian National Museum (Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum)

▲▲Great Synagogue (Nagy Zsinagóga)

Hungarian Jewish Archives and Family Research Center

▲▲Hungarian State Opera House (Magyar Állami Operaház)

▲▲House of Terror (Terror Háza)

Museum of Fine Arts (Szépművészeti Múzeum)

▲▲Vajdahunyad Castle (Vajdahunyad Vára)

▲▲▲Széchenyi Baths (Széchenyi Fürdő)

ON THE GREAT BOULEVARD (NAGYKÖRÚT)

▲▲Holocaust Memorial Center (Holokauszt Emlékközpont)

Applied Arts Museum (Iparművészeti Múzeum)

National Theater (Nemzeti Színház)

Palace of Arts (Művészetek Palotája)

▲Margaret Island (Margitsziget)

▲Hungarian National Gallery (Magyar Nemzeti Galéria)

Budapest History Museum (Budapesti Történeti Múzeum)

▲Buda Castle Park and Grand Staircase (Várkert Bazár)

▲▲Matthias Church (Mátyás-Templom)

Fishermen’s Bastion (Halászbástya)

Remains of St. Mary Magdalene Church

Museum of Military History (Hadtörténeti Múzeum)

▲Hospital in the Rock and Nuclear Bunker (Sziklakórház és Atombunker)

Labyrinth of Buda Castle (Budavári Labirintus)

GELLÉRT HILL (GELLÉRTHEGY) AND NEARBY

▲Imre Varga Collection (Varga Imre Gyűjtemény)

▲▲MEMENTO PARK (A.K.A. STATUE PARK)

The sights listed in this chapter are arranged by neighborhood for handy sightseeing. When you see a  in a listing, it means the sight is covered in much more depth in one of my walks or self-guided tours. This is why Budapest’s most important attractions get the least coverage in this chapter—we’ll explore them later in the book. For tips on sightseeing, see here.

in a listing, it means the sight is covered in much more depth in one of my walks or self-guided tours. This is why Budapest’s most important attractions get the least coverage in this chapter—we’ll explore them later in the book. For tips on sightseeing, see here.

Budapest boomed in the late 19th century, after it became the co-capital of the vast Habsburg Empire. Most of its finest buildings (and top sights) date from this age. To appreciate an opulent interior—a Budapest experience worth ▲▲▲—I strongly recommend touring either the Parliament or the Opera House, depending on your interests. The Opera tour is more crowd-pleasing, while the Parliament tour is a bit drier (with a focus on history and parliamentary process)—but the spaces are even grander. Seeing both is also a fine option. “Honorable mentions” go to the interiors of St. István’s Basilica, the Great Synagogue, New York Café, and both the Széchenyi and the Gellért Baths. This diversity—government and the arts, Christian and Jewish, coffee-drinkers and bathers—demonstrates how the shared prosperity of the late 19th century made it a Golden Age for a broad cross section of Budapest society.

The early 21st century has also been a boom time in Budapest. Many formerly dreary squares, parks, and streets have been refurbished, as have many museums. The latest plan is to create an ambitious “Museum Quarter” in City Park, which will be the new home to the National Gallery and museums of contemporary art (Ludwig collection), ethnography, photography, architecture, and music. However, this is unlikely to happen before 2018 (though construction may be underway when you visit—see www.ligetbudapest.org for details).

Remember, most sights in town offer a discount if you buy a Budapest Card (described on here). If you have a Budapest Card, always ask about discounts when you buy your ticket.

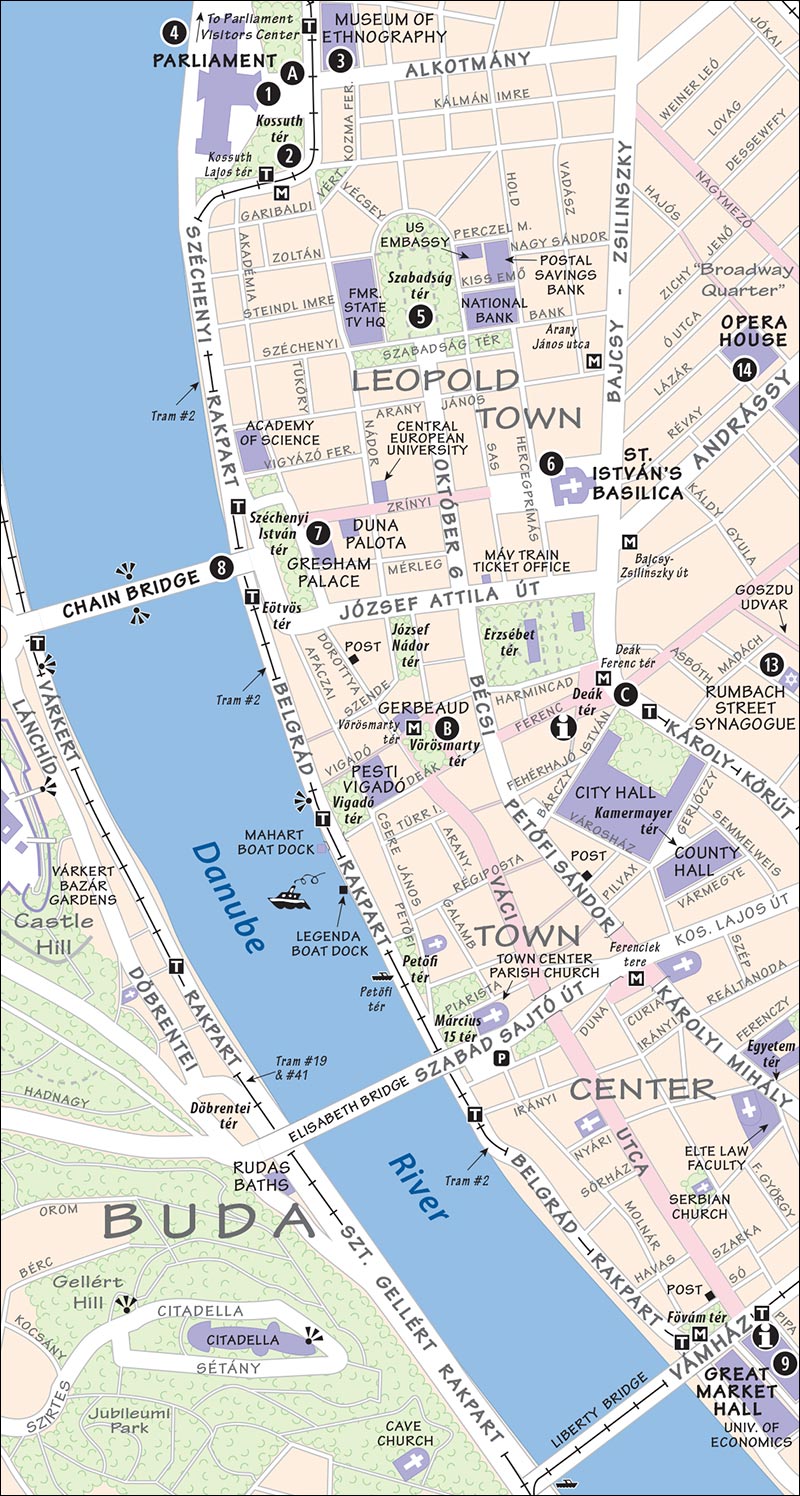

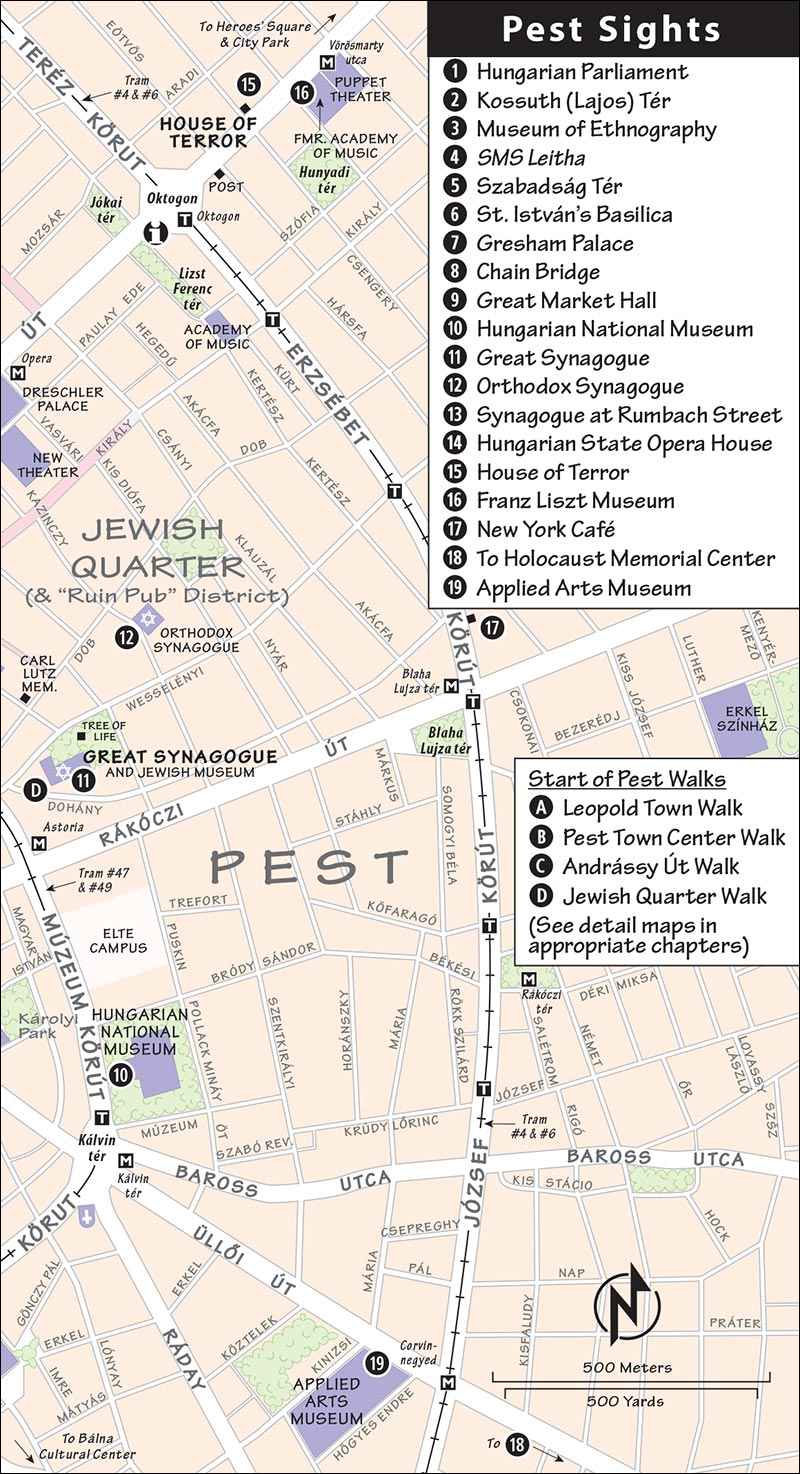

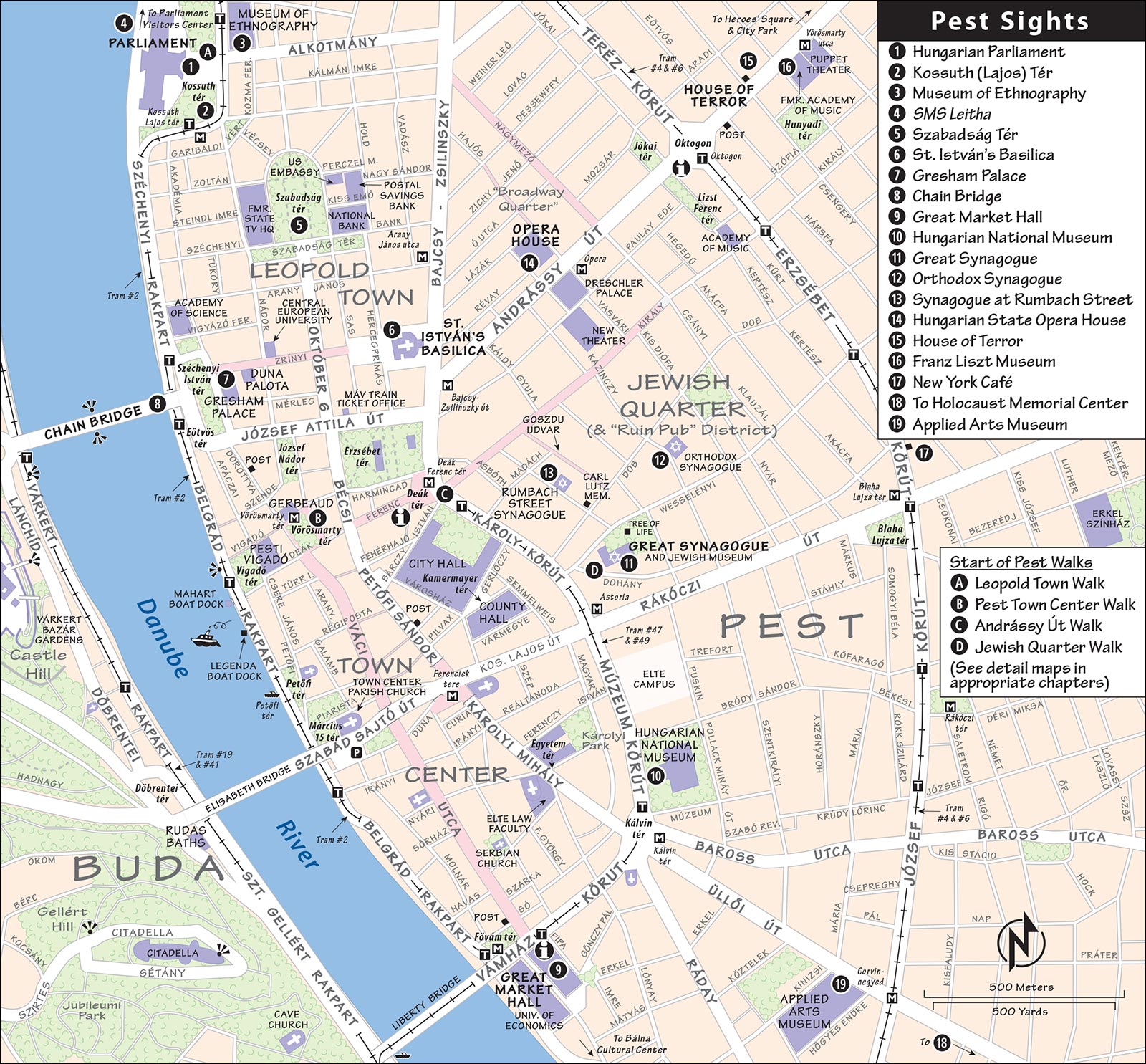

Most of Pest’s top sights cluster in four neighborhoods: Leopold Town and the Town Center (together forming the city’s “downtown,” along the Danube); along Andrássy út; and at Heroes’ Square and City Park. Each of these areas is covered by a separate self-guided walk (as noted by  below). The Jewish Quarter is covered in the Great Synagogue and Jewish Quarter Tour chapter.

below). The Jewish Quarter is covered in the Great Synagogue and Jewish Quarter Tour chapter.

Several other excellent sights are not contained in these areas, and are covered in greater depth in this chapter: along the Small Boulevard (Kiskörút); along the Great Boulevard (Nagykörút); and along the boulevard called Üllői út.

Most of these sights are covered in detail in the Leopold Town Walk chapter. If a sight is covered in the walk, I’ve listed only its essentials here. These are listed north to south.

Most of these sights are covered in detail in the Leopold Town Walk chapter. If a sight is covered in the walk, I’ve listed only its essentials here. These are listed north to south.

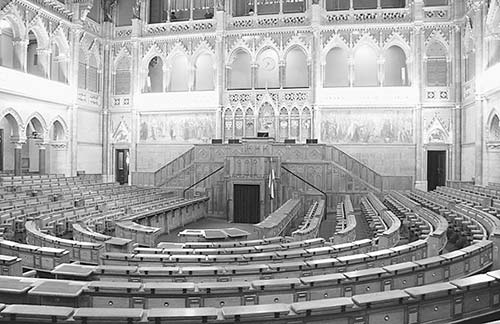

With an impressive facade and an even more extravagant interior, the oversized Hungarian Parliament dominates the Danube riverbank. A hulking Neo-Gothic base topped by a soaring Neo-Renaissance dome, it’s one of the city’s top landmarks. Touring the building offers the chance to stroll through one of Budapest’s best interiors. While the guides can be hit-or-miss, the dazzling building speaks for itself.

Cost and Hours: 5,000 Ft, half-price for EU citizens if you show your passport; English tours usually daily at 10:00, 12:00, 13:00, 14:00, and 15:00—but there can be more tours with demand, or fewer for no apparent reason, so confirm in advance; on Mon when parliament is in session—generally Sept-May—the only English tour is generally at 10:00 (and likely to sell out).

Getting There: Ride tram #2 to the Országház stop, which is next to the visitors center entrance (Kossuth tér 1, district V, M2: Kossuth tér).

Getting Tickets: Tickets come with an appointed tour time and often sell out. To ensure getting a space, it’s worth paying an extra 200 Ft per ticket to book online a day or two in advance at www.jegymester.hu. Select “Parliament Visit,” then a date and time of an English tour, and be sure to specify “full price” (unless you have an EU passport). You’ll have to create an account, but it’s no problem to use a US address, telephone number, and credit card. Print out your eticket and show up at the Parliament visitors center at the appointed time (if you can’t print it, show up early enough to have them print it out for you at the ticket desk—which can have long lines, especially in the morning).

If you didn’t prebook a ticket, go to the visitors center—a modern, underground space at the northern end of the long Parliament building (look for the statue of a lion on a pillar)—and ask what the next available tour time is. While the first English tour of the day is almost always sold out with online tickets, later tours (especially in the afternoon) may have space. The visitors center and ticket desk are open Mon-Fri 8:00-18:00 (or until 16:00 in Nov-March), Sat-Sun 8:00-16:00, and only sell tickets for the same day—if booking in advance, you need to use the website.

Information: Tel. 1/441-4904, www.parlament.hu.

Visiting the Parliament: The visitors center has WCs, a café, a gift shop, and a Museum of the History of the Hungarian National Assembly. Once you have your ticket in hand, be at the security checkpoint inside the visitors center at least five minutes before your tour departure time.

On the 45-minute tour, your guide will explain the history and symbolism of the building’s intricate decorations and offer a lesson in the Hungarian parliamentary system. You’ll see dozens of bushy-mustachioed statues illustrating the occupations of workaday Hungarians through history, and find out why a really good speech was nicknamed a “Havana” by cigar-aficionado parliamentarians.

To begin the tour, you’ll climb a 133-step staircase (with an elevator for those who need it) to see the building’s monumental entryway and 96-step grand staircase—slathered in gold foil and frescoes, and bathed in shimmering stained-glass light. Then you’ll gape up under the ornate gilded dome for a peek at the heavily guarded Hungarian crown (described on here), which is overlooked by statues of 16 great Hungarian monarchs, from St. István to Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa. Finally, you’ll walk through a cushy lounge—across one of Europe’s largest carpets—to see the legislative chamber.

The giant square surrounding the Parliament is peppered with monuments honoring great Hungarian statesmen (Lajos Kossuth, Ferenc Rákóczi, Imre Nagy), artists (Attila József), and anonymous victims of past regimes (underfoot is a memorial to the 1956 Uprising, during which protesters were gunned down on this very square).

For more details about Kossuth tér,  see the Leopold Town Walk chapter.

see the Leopold Town Walk chapter.

The square is fronted by the...

This museum, housed in one of Budapest’s majestic venues, feels deserted. Its fine collection of Hungarian folk artifacts (mostly from the late 19th century) takes up only a small corner of the cavernous building. The permanent exhibit, with surprisingly good English explanations, shows off costumes, tools, wagons, boats, beehives, furniture, and ceramics of the many peoples who lived in pre-WWI Hungary (which also included much of today’s Slovakia and Romania). The museum also has a collection of artifacts from other European and world cultures, which it cleverly assembles into good temporary exhibits.

Cost and Hours: 1,000 Ft for permanent collection, more for temporary exhibits, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon, Kossuth tér 12, district V, M2: Kossuth tér, tel. 1/473-2200, www.neprajz.hu.

For more details on all of the following sights,  see the Leopold Town Walk chapter.

see the Leopold Town Walk chapter.

One of Budapest’s most genteel squares, this space is marked by a controversial monument to the Soviet soldiers who liberated Hungary at the end of World War II, and ringed by both fancy old apartment blocks and important buildings (such as the former Hungarian State Television headquarters, the US Embassy, and the National Bank of Hungary). A fine café, fun-filled playgrounds, statues of prominent Americans (Ronald Reagan and Harry Hill Bandholtz), and yet another provocative monument (to the Hungarian victims of the Nazis) round out the square’s many attractions. More architectural gems—including the quintessentially Art Nouveau Bedő-Ház and the Postal Savings Bank in the Hungarian national style—are just a block away.

Budapest’s biggest church is one of its top landmarks. The grand interior celebrates St. István, Hungary’s first Christian king. You can see his withered, blackened, millennium-old fist in a gilded reliquary in the side chapel. Or you can zip up on an elevator (or climb up stairs partway) to a panorama terrace with views over the rooftops of Pest. The skippable treasury has ecclesiastical items, historical exhibits, and artwork.

Cost and Hours: Interior—free but 200-Ft donation strongly suggested, open to tourists Mon 9:00-16:30, Tue-Fri 9:00-17:00, Sat 9:00-13:00, Sun 13:00-17:00, open slightly later for worshippers; panorama terrace—500 Ft, daily June-Sept 10:00-18:30, March-May and Oct 10:00-17:30, Nov-Feb 10:00-16:30; treasury-400 Ft, same hours as terrace; Szent István tér, district V, M1: Bajcsy-Zsilinszky út or M3: Arany János utca.

This stately old Art Nouveau building, long neglected, has now been renovated to its former splendor. Overlooking Széchenyi tér, it once held the offices of a life-insurance company; today it houses one of Budapest’s top hotels. Even if you’re not a guest, ogle its glorious facade and stroll through its luxurious lobby (lobby open 24 hours daily, Széchenyi tér 5, district V, M1: Vörösmarty tér or M2: Kossuth tér, www.fourseasons.com/budapest).

The city’s most beloved bridge stretches from Pest’s Széchenyi tér to Buda’s Adam Clark tér (named for the bridge’s designer). The gift of Count István Széchenyi to the Hungarian people, the Chain Bridge was the first permanent link between the two towns that would soon merge to become Budapest.

All of these sights are covered in detail in the Pest Town Center Walk chapter. I’ve listed only the essentials here.

All of these sights are covered in detail in the Pest Town Center Walk chapter. I’ve listed only the essentials here.

The central square of the Town Center, dominated by a giant statue of the revered Romantic poet Mihály Vörösmarty and the venerable Gerbeaud coffee shop, is the hub of Pest sightseeing. Within a few steps of here are the main walking street, Váci utca (described next), the delightful Danube promenade, the “Fashion Street” of Deák utca, and much more.

In Budapest’s Golden Age, Váci Street was where well-heeled urbanites would shop, then show off for one another. During the Cold War, it was the first place in the Eastern Bloc where you could buy a Big Mac or Adidas sneakers. And today, it’s an overrated, overpriced tourist trap disguised as a pretty street. I’ll admit that I have a bad attitude about Váci utca. It’s because more visitors get fleeced by dishonest shops, crooked restaurants, and hookers masquerading as lonely hearts here than anywhere else in town. Like moths to a flame, tourists can’t seem to avoid this strip. Walk Váci utca to satisfy your curiosity. But then venture off it to discover the real Budapest.

“Great” indeed is this gigantic marketplace on three levels: produce, meats, and other foods on the ground floor; souvenirs upstairs; and fish and pickles in the cellar. The Great Market Hall has somehow succeeded in keeping local shoppers happy, even as it’s evolved into one of the city’s top tourist attractions. Goose liver, embroidered tablecloths, golden Tokaji Aszú wine, pickled peppers, communist-kitsch T-shirts, savory lángos pastries, patriotic green-white-and-red flags, kid-pleasing local candy bars, and paprika of every degree of spiciness...if it’s Hungarian, you’ll find it here. Come to shop for souvenirs, to buy a picnic, or just to rattle around inside this vast, picturesque, Industrial Age hall.

Hours and Location: Mon 6:00-17:00, Tue-Fri 6:00-18:00, Sat 6:00-15:00, closed Sun, Fővám körút 1, district IX, M4: Fővám tér or M3: Kálvin tér.

This shopping mall and cultural center stands along the riverbank behind the Great Market Hall. Completed in 2013, the complex was created by bridging a pair of circa-1881 brick warehouses with a swooping glass canopy that earns its name, “The Whale” (the meaning of bálna). The architecture is striking (especially from the river), and the space inside is sleek and modern, but the building has been controversial for not really having a clear purpose: It’s partly filled with boutiques and galleries of local designers (making it worth a browse for items you won’t find in the Great Market Hall), but also houses conference and concert space, offices, and several eateries—including several with enticing outdoor seating along the embankment. It still feels unmoored, with several vacant storefronts, but it may eventually live up to its potential. Shoppers and fans of contemporary architecture may find it worth the three-minute stroll beyond the back door of the Great Market Hall.

Cost and Hours: Free to enter, Sun-Thu 10:00-20:00, Fri-Sat 10:00-22:00, www.balnabudapest.hu.

These two major sights are along the Small Boulevard, between the Liberty Bridge/Great Market Hall and Deák tér. (Note that the Great Market Hall, listed earlier, is also technically along the Small Boulevard.)

One of Budapest’s biggest museums features all manner of Hungarian historic bric-a-brac, from the Paleolithic age to a more recent infestation of dinosaurs (the communists). Artifacts are explained by good, if dry, English descriptions.

Cost and Hours: 1,600 Ft—but can change depending on temporary exhibits, audioguide available, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon, last entry 30 minutes before closing, near Great Market Hall at Múzeum körút 14, district VIII, M3: Kálvin tér, tel. 1/327-7773, www.hnm.hu.

Visiting the Museum: The first floor (one flight down from the entry) focuses on the Carpathian Basin in the pre-Magyar days, with ancient items and Roman remains. The basement features a lapidarium, with medieval tombstones and more Roman ruins.

Upstairs, 20 rooms provide a historic overview from the arrival of the Magyars in 896 up to the 1989 revolution. The museum adds substance to your understanding of Hungary’s story—but it helps to have a pretty firm foundation first (read this book’s Hungary: Past and Present chapter). The most engaging part is room 20, with an exhibit on the communist era, featuring both pro- and anti-Party propaganda. The exhibit ends with video footage of the 1989 end of communism—demonstrations, monumental parliament votes, and a final farewell to the last Soviet troops leaving Hungarian soil. You’ll also see the pen used to un-sign the Warsaw Pact in 1991, and current Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s rucksack—a children’s backpack decorated with soccer players—which he carried around throughout his first term as evidence of his connection to the common man. (Now wedded to the gimmick, he’s still carrying a bag like this.) Another uprising—the 1848 Revolution against Habsburg rule—was declared from the steps of this impressive Neoclassical building.

The Great Synagogue and other sights in this area are described in far greater detail in the Great Synagogue and Jewish Quarter Tour chapter.

The Great Synagogue and other sights in this area are described in far greater detail in the Great Synagogue and Jewish Quarter Tour chapter.

The world’s second biggest synagogue sits tucked behind a workaday building on the Small Boulevard. Dating from the mid-19th century—a time when Budapest’s Jews were eager to feel integrated with the larger community—this synagogue, with two dominant towers and a longitudinal plan, feels more like a Christian building than a Jewish one. The gorgeously restored, intricately decorated interior is one of Budapest’s finest. Attached to the synagogue is the small but well-presented Hungarian Jewish Museum, and behind it is an evocative memorial garden with the powerful Tree of Life monument to Hungarian victims of the Holocaust, as well as a symbolic grave for Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who worked to save the lives of Hungarian Jews during World War II. The synagogue is also a starting point for various tours both of the building itself, and of the surrounding Jewish sights.

Cost and Hours: 2,500 Ft for Great Synagogue, Hungarian Jewish Museum, and Memorial Garden (or pay 500 Ft just for just the garden), 500 Ft extra to take photos; March-Oct Sun-Thu 10:00-18:00, Fri 10:00-16:30—until 15:30 in March; Nov-Feb Sun-Fri 10:00-16:00; always closed Sat and Jewish holidays, last entry 30 minutes before closing; Dohány utca 2, district VII, near M2: Astoria or the Astoria stop on trams #47 and #49, tel. 1/344-5131, www.dohanyutcaizsinagoga.hu.

At the back of the Great Synagogue’s memorial garden, this facility houses a small exhibit about the Jewish Quarter and an archive of Jewish birth, marriage, and death records.

Cost and Hours: Exhibit covered by Great Synagogue ticket, 1,000 Ft to use archives, Mon-Wed 10:00-17:00, Thu 12:00-17:00, Fri 10:00-15:00, closed Sat-Sun, closes one hour earlier Nov-Feb, Wesselényi utca 7, best to call or email ahead to arrange help with archives, tel. 1/413-5547, www.milev.hu, family@milev.hu.

This colorfully decorated space is Budapest’s second-most-interesting Jewish sight. It’s just two blocks behind the Great Synagogue.

Cost and Hours: 1,000 Ft, Sun-Thu 10:00-16:00, Fri 10:00-13:30, closed Sat, enter down little alley, Kazinczy utca 27, district VII, M2: Astoria.

This fine house of worship, designed by Otto Wagner and with a faded Moorish-style interior, may close soon for a much-needed restoration.

Cost and Hours: If open—likely 500 Ft, Sun-Thu 10:00-17:30, Fri 10:00-15:30, closed Sat. From the Tree of Life it’s two blocks down Rumbach utca toward Andrássy út (district VII, M2: Astoria).

All of these sights are covered in detail in the Andrássy Út Walk chapter, with the exception of the House of Terror, which is further described in the House of Terror Tour chapter. I’ve listed only the essentials here.

All of these sights are covered in detail in the Andrássy Út Walk chapter, with the exception of the House of Terror, which is further described in the House of Terror Tour chapter. I’ve listed only the essentials here.

This sumptuous temple to music is one of Europe’s finest opera houses. Built in the late 19th century by patriotic Hungarians striving to thrust their capital onto the European stage, it also boasts one of Budapest’s very best interiors.

You can drop in whenever the box office is open to ogle the ostentatious lobby (Mon-Sat from 11:00 until show time—generally 19:00, or until 17:00 if there’s no performance; Sun open 3 hours before the performance—generally 16:00-19:00, or 10:00-13:00 if there’s a matinee; Andrássy út 22, district VI, M1: Opera).

The 45-minute tours of the Opera House are a must for music lovers, and enjoyable for anyone, though the quality of the guides can be erratic: Most spout plenty of fun, if silly, legends, but others can be quite dry. You’ll see the main entryway, the snooty lounge area, some of the cozy but plush boxes, and the lavish auditorium. You’ll find out why clandestine lovers would meet in the cigar lounge, how the Opera House is designed to keep the big spenders away from the rabble in the nosebleed seats, and how to tell the difference between real marble and fake marble (2,900 Ft, 500 Ft extra to take photos, 600 Ft extra for 5-minute mini-concert of two arias after the tour; English tours nearly daily at 15:00 and 16:00, June-Oct maybe also at 14:00; tickets are easy to get—just show up 10 minutes before the tour; buy ticket in opera shop—enter the main lobby and go left, shop open daily 11:00-18:00—or until the end of the second intermission during performances, Oct-March closed for lunch 13:30-14:00; tel. 1/332-8197). Since the real appeal is the chance to see the interior, skip the tour if you’re going to an opera performance.

The building at Andrássy út 60 was home to the vilest parts of two destructive regimes: first the Arrow Cross (the Gestapo-like enforcers of Nazi-occupied Hungary), then the ÁVO and ÁVH secret police (the insidious KGB-type wing of the Soviet satellite government). Now re-envisioned as the “House of Terror,” this building uses high-tech, highly conceptual, bombastic exhibits to document (if not proselytize about) the ugliest moments in Hungary’s difficult 20th century. Enlightening and well-presented, it rivals Memento Park as Budapest’s best attraction about the communist age.

Cost and Hours: 2,000 Ft, possibly more for special exhibits, audioguide-1,500 Ft, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon, last entry 30 minutes before closing, Andrássy út 60, district VI, M1: Vörösmarty utca—not the Vörösmarty tér stop, tel. 1/374-2600, www.terrorhaza.hu.

See the House of Terror Tour chapter.

See the House of Terror Tour chapter.

In this surprisingly modest apartment where the composer once resided, you’ll find a humble but appealing collection of artifacts. A pilgrimage site for Liszt fans, it’s housed in the former Academy of Music, which also hosts Saturday-morning concerts (see here).

Cost and Hours: 1,300 Ft; dry English audioguide with a few snippets of music-700 Ft, otherwise scarce English information—borrow the information sheet as you enter; Mon-Fri 10:00-18:00, Sat 9:00-17:00, closed Sun, Vörösmarty utca 35, district VI, M1: Vörösmarty utca—not Vörösmarty tér stop, tel. 1/322-9804, www.lisztmuseum.hu.

All of these sights are covered in detail in the Heroes’ Square and City Park Walk chapter, with the exception of Széchenyi Baths, which are described in the Thermal Baths chapter. I’ve listed only the essentials here. To reach this area, take the M1/yellow Metró line to Hősök tere (district XIV).

All of these sights are covered in detail in the Heroes’ Square and City Park Walk chapter, with the exception of Széchenyi Baths, which are described in the Thermal Baths chapter. I’ve listed only the essentials here. To reach this area, take the M1/yellow Metró line to Hősök tere (district XIV).

Built in 1896 to celebrate the 1,000th anniversary of the Magyars’ arrival in Hungary, this vast square culminates at a bold Millennium Monument. Standing stoically in its colonnades are 14 Hungarian leaders who represent the whole span of this nation’s colorful and illustrious history. In front, at the base of a high pillar, are the seven original Magyar chieftains, the Hungarian War Memorial, and young Hungarian skateboarders of the 21st century. It’s an ideal place to appreciate Budapest’s greatness and to learn a little about its story. The square is also flanked by a pair of museums (described next).

For a statue-by-statue self-guided tour of Heroes’ Square,  see the Heroes’ Square and City Park Walk chapter.

see the Heroes’ Square and City Park Walk chapter.

This collection of Habsburg art—mostly Germanic, Dutch, Belgian, and Spanish, rather than Hungarian—is Budapest’s best chance to appreciate some European masters. It’s likely closed for renovation through 2017.

Cost and Hours: If open—likely 1,800 Ft, may be more for special exhibits, audioguide-500 Ft, WC and coat check downstairs, Tue-Sun 10:00-17:30, closed Mon, last entry 30 minutes before closing, Dózsa György út 41, tel. 1/469-7100, www.szepmuveszeti.hu.

Facing the Museum of Fine Arts from across Heroes’ Square, the Műcsarnok shows temporary exhibits by contemporary artists—of interest only to art lovers. The price varies depending on the exhibits and on which parts you tour.

Cost and Hours: 1,800 Ft, Tue-Wed and Fri-Sun 10:00-18:00, Thu 12:00-20:00, closed Mon, Dózsa György út 37, tel. 1/460-7000, www.mucsarnok.hu.

This particularly enjoyable corner of Budapest, which sprawls behind Heroes’ Square, is endlessly entertaining. Explore the fantasy castle of Vajdahunyad (described next). Visit the animals and ogle the playful Art Nouveau buildings inside the city’s zoo, ride a roller-coaster at the amusement park, or enjoy a circus under the big top (all described in the Budapest with Children chapter). Go for a stroll, rent a rowboat, eat some cotton candy, or challenge a local Bobby Fischer to a game of chess. Or, best of all, take a dip in Budapest’s ultimate thermal spa, the Széchenyi Baths (described later). This is a fine place to just be on vacation.

An elaborate pavilion that the people of Budapest couldn’t bear to tear down after their millennial celebration ended a century ago, Vajdahunyad Castle has become a fixture of City Park. Divided into four parts—representing four typical, traditional schools of Hungarian architecture—this “little Epcot” is free and always open to explore. It’s dominated by a fanciful replica of a Renaissance-era Transylvanian castle. Deeper in the complex, a curlicue-covered Baroque mansion houses (unexpectedly) the Museum of Hungarian Agriculture, noteworthy for its grand interior (Magyar Mezőgazdasági Múzeum; 1,100 Ft; April-Oct Tue-Sun 10:00-17:00; Nov-March Tue-Fri 10:00-16:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-17:00; closed Mon year-round, last entry 30 minutes before closing, tel. 1/363-1117, www.mezogazdasagimuzeum.hu).

My favorite activity in Budapest, the Széchenyi Baths are an ideal way to reward yourself for the hard work of sightseeing and call it a culturally enlightening experience. Soak in hundred-degree water, surrounded by portly Hungarians squeezed into tiny swimsuits, while jets and cascades pound away your tension. Go for a vigorous swim in the lap pool, giggle and bump your way around the whirlpool, submerge yourself to the nostrils in water green with minerals, feel the bubbles from an underwater jet gradually caress their way up your leg, or challenge the locals to a game of Speedo-clad chess. And it’s all surrounded by an opulent yellow palace with shiny copper domes. The bright blue-and-white of the sky, the yellow of the buildings, the pale pink of the skin, the turquoise of the water...Budapest simply doesn’t get any better.

Cost and Hours: 4,500 Ft for locker (in gender-segregated locker room), 500 Ft more for personal changing cabin, cheaper after 19:00, 200 Ft more on weekends; admission includes outdoor swimming pool area, indoor thermal baths, and sauna; swimming pool generally open daily 6:00-22:00, thermal bath daily 6:00-19:00, may be open later on summer weekends, last entry one hour before closing, Állatkerti körút 11, district XIV, M1: Széchenyi fürdő, tel. 1/363-3210, www.szechenyibath.hu.

See the Thermal Baths chapter.

See the Thermal Baths chapter.

My vote for the most over-the-top extravagant coffeehouse in Budapest, if not Europe, this restored space ranks up there with the city’s most impressive old interiors. Springing for a pricey cup of coffee here (consider it the admission fee) is worth it simply to soak in all the opulence.

Cost and Hours: Free to take a quick peek, pricey coffee and meals, daily 9:00-24:00, Erzsébet körút 9, district VII, M2: Blaha Lujza tér, tel. 1/886-6167. For more details, see here of the Eating in Budapest chapter.

These two areas—a short commute to the south from the center of Pest (10-15 minutes by tram or Metró)—offer a peek at some worthwhile, workaday areas where relatively few tourists venture.

These two museums are near the city center, on the boulevard called Üllői út. You could stroll there in about 10 minutes from the Small Boulevard ring road (walking the length of the Ráday utca café street gets you very close), or hop on the M3/blue Metró line to Corvin-negyed (just one stop beyond Kálvin tér).

This sight honors the nearly 600,000 Hungarian victims of the Nazis...one out of every ten Holocaust victims. The impressive modern complex (with a beautifully restored 1920s synagogue as its centerpiece) is a museum of the Hungarian Holocaust, a monument to its victims, a space for temporary exhibits, and a research and documentation center of Nazi atrocities. Interesting to anybody, but essential to those interested in the Holocaust, this is Budapest’s best sight about that dark time—and one of Europe’s best, as well. (For background on the Hungarian Jewish experience, see here.)

Cost and Hours: 1,400 Ft, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon, Páva utca 39, district IX, M3: Corvin-negyed, tel. 1/455-3333, www.hdke.hu.

Getting There: From the Corvin-negyed Metró stop, use the exit marked Holokauszt Emlékközpont and take the left fork at the exit. Walk straight ahead two long blocks, then turn right down Páva utca.

Visiting the Center: You’ll pass through a security checkpoint to reach the courtyard. Once inside, a black marble wall is etched with the names of victims. Head downstairs to buy your ticket.

The excellent permanent exhibit, called “From Deprivation of Rights to Genocide,” traces in English the gradual process of disenfranchisement, marginalization, exploitation, dehumanization, and eventually extermination that befell Hungary’s Jews as World War II wore on. From the entrance, a long hallway with shuffling feet on the soundtrack replicates the forced march of prisoners. The one-way route through darkened halls uses high-tech exhibits, including interactive touch screens and movies, to tell the story. By demonstrating that pervasive anti-Semitism existed here long before World War II, the pointed commentary casts doubt on the widely held belief that Hungary initially allied itself with the Nazis partly to protect its Jews. While the exhibit sometimes acknowledges Roma (Gypsy) victims, its primary focus is on the fate of the Hungarian Jews. Occasionally the exhibit zooms in to tell the story of an individual or a single family, following their personal story through those horrific years. One powerful room is devoted to the notorious Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, where some 430,000 Hungarian Jews were sent—most to be executed immediately upon arrival. The main exhibit ends with a thoughtful consideration of “Liberation and Calling to Account,” analyzing the impossible question of how a society responds to and recovers from such a tragedy.

The finale is the interior of the synagogue, now a touching memorial filled with glass seats, each one etched with the image of a Jewish worshipper who once filled it. Up above, on the mezzanine level, you’ll find temporary exhibits and an information center that helps teary-eyed descendants of Hungarian Jews track down the fate of their relatives.

This remarkable late-19th-century building, a fanciful green-roofed castle that seems out of place in an otherwise dreary urban area, was designed by Ödön Lechner (who also did the Postal Savings Bank—see here). The interior is equally striking: Because historians of the day were speculating about possible ties between the Magyars and India, Lechner decorated it with Mogul motifs (from the Indian dynasty best known for the Taj Mahal). Strolling through the forest of dripping-with-white-stucco arches and columns, you might just forget to pay attention to the exhibits...which would be a shame. This is the third-oldest applied arts institution in the world (after ones in London and Vienna). The small but excellent permanent collection upstairs, called “Collectors and Treasures,” displays furniture, clothes, ceramics, and other everyday items, with an emphasis on curvy Art Nouveau (all described in English). This and various temporary exhibits are displayed around a light and airy atrium. If you’re visiting the nearby Holocaust Memorial Center, consider dropping by here for a look at the building.

Cost and Hours: Ticket price varies with exhibits, but generally around 2,000-3,000 Ft, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon, Üllői út 33, district IX, M3: Corvin-negyed, tel. 1/456-5100, www.imm.hu.

Getting There: From the Corvin-negyed Metró stop, follow signs to Iparművészeti Múzeum and bear right up the stairs.

Along the Danube riverbank at the Rákóczi Bridge, you’ll find a cutting-edge cultural complex with some of Budapest’s best modern venues for music and theater. While there’s not much “sightseeing” here (aside from a contemporary art gallery and the quirky distillery museum), it’s fun to wander the riverside park amid the impressive buildings. A row of super-modern glass office blocks effectively seals off the inviting park from the busy highway, creating a pleasant place to simply stroll. (Don’t confuse this with the similarly named Millenáris Park, at the northern edge of Buda.)

Getting There: Though it looks far on the map, this area is easy to reach: From anywhere along the Pest embankment (including Kossuth tér by the Parliament, Vigadó tér in the heart of Pest’s Town Center, or Fővám tér next to the Great Market Hall), hop on tram #2 and ride it south about 10-15 minutes to the Millenniumi Kulturális Központ stop.

This facility anchors the complex with an elaborate industrial-Organic facade, studded with statues honoring the Hungarian theatrical tradition. The surrounding park is a lively people zone laden with whimsical art—Hungarian theater greats in stone, a vast terrace shaped like a ship’s prow, a toppled colonnade, and a stone archway that evokes an opening theater curtain. Twist up to the top of the adjacent, yellow-brick ziggurat tower for fine views over the entire complex and all the way to downtown Budapest.

With a sterner facade, this gigantic facility houses the 1,700-seat Béla Bartók National Concert Hall and the smaller 460-seat Festival Theater (free to enter the building, open daily 10:00-20:00 or until end of last performance, www.mupa.hu). The complex is also home to the Ludwig Museum, Budapest’s premier collection of contemporary art, with mostly changing exhibits of today’s biggest names (price varies depending on exhibits, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, temporary exhibits may stay open until 20:00, closed Mon, Komor Marcell utca 1, tel. 1/555-3444, www.ludwigmuseum.hu).

This museum and visitors center is housed in a corner of the sprawling distillery complex that produces Unicum, the abundantly flavored liquor that’s Hungary’s favorite spirit (described on here). The Zwack family is a Hungarian institution, like the Anheuser-Busch clan in the US. The museum offers a doting look at the Zwacks and their company, which has been headquartered right here since 1892 (with a 45-year break during communism). The Zwacks’ story is a fascinating case study in how communism affected longstanding industry—privatization, exile, and triumphant return (see below). And, while the Zwacks’ museum feels a bit like a shrine to their own ingenuity, it’s worthwhile for Unicum fans, or for anyone who enjoys learning how booze gets made. Hungary’s entire production of Unicum—three million liters annually—still takes place right here.

Cost and Hours: 1,800 Ft, Mon-Sat 10:00-18:00, tours in English at 14:00 and likely at other times—call ahead to check, closed Sun, Soroksári út 26, enter around the corner on Dandár utca, tel. 1/215-3575.

Getting There: It’s near the Haller utca stop on tram #2 (the stop just before Millennium Park); from the tram stop, walk back a block and head up Dandár utca.

Background: Unicum has a history as complicated as its flavor. Invented by a Doctor Zwack in the late 18th century, the drink impressed Habsburg Emperor Josef II, who supposedly declared: “Das ist ein Unikum!” (“This is a specialty!”). The Zwack company went on to thrive during Budapest’s late-19th-century Golden Age (when Unicum was the subject of many whimsical Guinness-type ads). Locals enjoy telling the story of how, after all of Budapest’s bridges spanning the Danube were destroyed in World War II, a temporary barge bridge was built from Unicum barrels. But when the communists took over in the postwar era, the Zwacks fled to America—taking their secret recipe for Unicum with them. The communists continued to market the drink with their own formula, which left Hungarians (literally and figuratively) with a bad taste in their mouths. In a landmark case, the Zwacks sued the communists for infringing on their copyright...and won. In 1991, Péter Zwack—who had been living in exile in Italy—triumphantly returned to Hungary and resurrected the original family recipe. More recently, to avoid alienating younger palates, they’ve added some smoother variations: Unicum Next (citrus) and Unicum Szilva (“plum”). But whatever the flavor, Unicum remains a proud national symbol.

Visiting the Museum: Your visit has three parts: a 20-minute film in English (more about the family than about their products); a fine little museum upstairs (glass display cases jammed with old ads, documents, and—up in the gallery—thousands of tiny bottles, includes English audioguide); and—the highlight—a guided tour of the refurbished original distillery building and the cellars where the spirit is aged. On this fascinating tour, you’ll be able to touch and smell several of the more than 40 herbs used to make Unicum, and learn about how the stuff gets made (components are distilled in two separate batches, then mixed and aged for six months). Then you’ll head down into the cellars where 500 gigantic, 10,000-liter oak casks offer the perfect atmosphere for sampling two types of Unicum straight from the barrel.

The mighty river coursing through the heart of the city defines Budapest. Make time for a stroll along the delightful riverfront embankments of both Buda and Pest. For many visitors, a highlight is taking a touristy but beautiful boat cruise up and down the Danube—especially at night (see “Tours in Budapest, By Boat” on here). Or visit the river’s best island...

In the Middle Ages, this island in the Danube (just north of the Parliament) was known as the “Isle of Hares.” In the 13th century, a desperate King Béla IV swore that if God were to deliver Hungary from the invading Tatars, he would dedicate his youngest daughter Margaret to the Church. Hungary was spared...and Margaret was shipped to a nunnery here. But, the story goes, Margaret embraced her new life as a castaway nun, and later refused her father’s efforts to force her into a politically expedient marriage with a Bohemian king. She became St. Margaret of Hungary, and this island was named for her.

The island remained largely undeveloped until the 19th century, when a Habsburg aristocrat built a hunting palace here and turned it into his playground. It gradually evolved into a lively garden district, connected to Buda and Pest by a paddleboat steamer. Eventually a bath and hotel complex was built (to take advantage of the island’s natural thermal springs), and Margaret Island was connected to the rest of the city in 1901 by the Margaret Bridge. In the genteel age of the late 19th century, a small entrance fee was charged to frolic on the island, to keep the rabble away.

Today, Margaret Island remains Budapest’s playground. While the island officially has no permanent residents, urbanites flock to relax in this huge, leafy park...in the midst of the busy city, yet so far away (no cars are allowed on the island—just public buses). The island rivals City Park as the best spot in town for strolling, jogging, biking, and people-watching. Margaret Island is also home to some of Budapest’s many baths, one of which (Palatinus Strandfürdő) is like a mini-water park. Rounding out the island’s attractions are an iconic old water tower, the remains of Margaret’s convent, a rose garden, a game farm, and a “musical fountain” that performs to the strains of Hungarian folk tunes.

Perhaps the best way to enjoy Margaret Island is to rent some wheels. Bringóhintó (“Bike Castle”), with branches at both ends of the island, rents all manner of wheeled entertainment (open daily year-round until dusk; location at Margaret Bridge opens at 10:00, at opposite end opens at 8:00; tel. 1/329-2746, www.bringohinto.hu). The main office is a few steps from the bus stop called “Szállodák (Hotels).” For two or more people, consider renting a fun bike cart—a four-wheeled carriage with two sets of pedals, a steering wheel, handbrake, and canopy (bikes—690 Ft/30 minutes, 990 Ft/1 hour, then 200 Ft/hour; bike carts—2,180 Ft/30 minutes, 3,480 Ft/1 hour; 20,000-Ft deposit or leave your ID). Because they have two locations, you can take bus #26 to the northern end of the island, rent a bike and pay the deposit, bike one-way to the southern tip of the island, and return your bike there to reclaim your deposit. Follow this route (using the helpful map posted inside the bike cart): water tower, monastery ruins, rose garden, past the game farm, along the east side of the island to the dancing fountain; with more time, go along the main road or the west side of the island to check out the baths.

Getting There: Bus #26 begins at Nyugati/Western train station, crosses the Margaret Bridge, then drives up through the middle of the island—allowing visitors to easily get from one end to the other (3-6/hour). Trams #4 and #6, which circulate around the Great Boulevard, cross the Margaret Bridge and stop at the southern tip of the island, a short walk from some of the attractions. You can also reach the island by boat; the public riverboats have two stops on the island (see here), or you can catch a Mahart shuttle boat from Vigadó tér (see here). It’s also a long but scenic walk between Margaret Island and other points in the city.

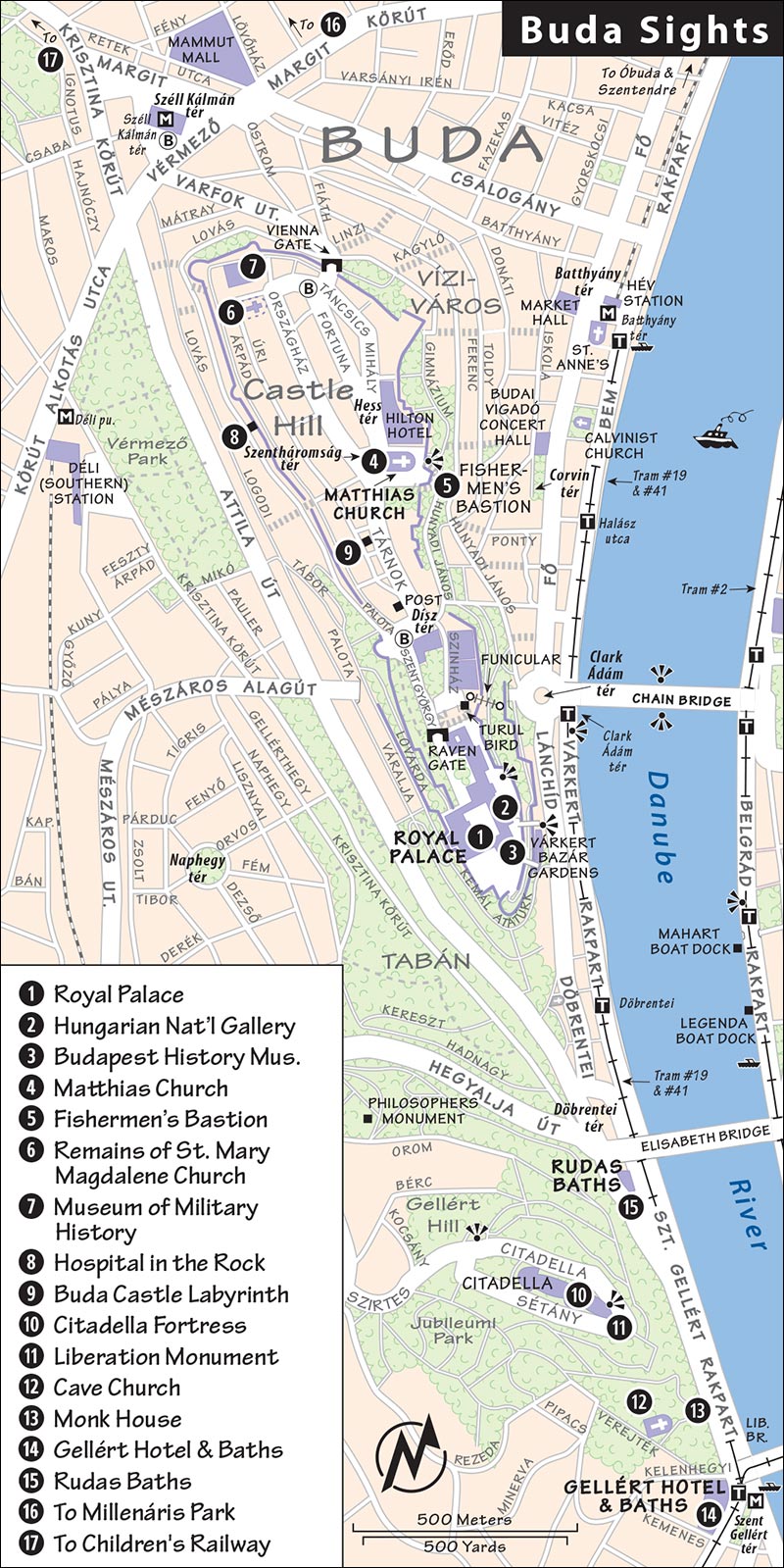

Nearly all of Buda’s top sights are concentrated on or near its two riverside hills: Castle Hill and Gellért Hill.

Most of these sights are covered in detail in the Castle Hill Walk chapter. If a sight is covered in the walk, I’ve listed only its essentials here.

Most of these sights are covered in detail in the Castle Hill Walk chapter. If a sight is covered in the walk, I’ve listed only its essentials here.

While imposing and grand-seeming from afar, the palace perched atop Castle Hill is essentially a shoddily rebuilt shell. But the terrace out front offers glorious Pest panoramas, there are signs of life in some of its nooks and crannies (such as a playful fountain depicting King Matthias’ hunting party), and the complex houses two museums (described next).

Hungarians are the first to admit that they’re not known for their artists. But this collection of Hungarian art—with an emphasis on the 19th and 20th centuries, and an excellent collection of medieval altars—offers even non-art lovers a telling glimpse into the Magyar psyche.

Cost and Hours: 1,400 Ft, may cost more for special exhibits, audioguide-800 Ft, 500 Ft extra to take photos, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon, required bag check for large bags, café, in the Royal Palace—enter from terrace by Eugene of Savoy statue, district I, mobile 0620-439-7325, www.mng.hu.

Self-Guided Tour: This once-over-lightly tour touches on the most insightful pieces in this sprawling museum.

Self-Guided Tour: This once-over-lightly tour touches on the most insightful pieces in this sprawling museum.

From the atrium, head up two flights on the grand staircase. When you reach the first floor, go through the second door on the right and walk through a room of gloomy paintings (which we’ll return to in a moment). Turn right into the hallway, then take an immediate left to reach the excellent collection of 15th-century winged altars. The ornately decorated wings could be opened or closed to acknowledge special occasions and holidays. Most of these come from “Upper Hungary,” or today’s Slovakia—which is more heavily wooded than modern (Lower) Hungary, making woodcarving a popular way to worship there. These date from a time when Hungary was at its peak—before the Ottomans and Habsburgs ruined everything.

Backtrack to the room of gloomy paintings from the 1850s and 1860s. We’ve just gone from one of Hungary’s highest points to one of its lowest. In the two decades between the failed 1848 Revolution and the Compromise of 1867, the Hungarians were colossally depressed—and these paintings show it. Take a moment to psychoanalyze this moment in Hungarian history, perusing the paintings in these two rooms.

Begin in the farther room, closer to the atrium. On the left wall is a painting of a corpse covered by a blood-stained sheet—Viktor Madarász’s grim The Bewailing of László Hunyadi, which commemorates the death of the beloved Hungarian heir-apparent. (The Hungarians couldn’t explicitly condemn their Habsburg oppressors, but invoking this dark event from the Middle Ages had much the same effect.) Another popular theme of this era was the Ottoman invasion of Hungary—another stand-in for unwanted Habsburg rule. In this room, two different paintings illustrate the tale of Mihály Dobozi, a Hungarian nobleman who famously stabbed his wife (at her insistence) to prevent her from being raped. In the canvas just to the right, we see her baring her breast, waiting to be slain; across the room, we see a different version, in which Dobozi literally stabs her while on horseback, fleeing from the invaders. While Hungarian culture tends to be less than upbeat, this period took things to a new low.

Flanking the door into the next room are two paintings that are as optimistic as the Hungarians could muster. In both cases, people are preparing to fight off their enemies: On the left, Imre Thököly takes leave of his father (likely for the last time) as he prepares to take to the battlefield against the Habsburgs; on the right, the women of the town of Eger stand strong against an Ottoman siege (for the full story, see here).

More gloominess awaits in the next room, however. On the right wall, the corpse of King Louis II is discovered after the Battle of Mohács, and the hero of the Battle of Belgrade gestures to his compatriots before falling to a valiant death. But on the facing wall, more positive themes come up: Matthias Corvinus is returning from a hunting expedition to his family’s Transylvanian palace. Two sculptures of the “Good King Matthias” are also displayed in this room. During dark times, Hungarians looked back to this powerful Renaissance king.

Finally, the large canvas dominating the room represents a turning point: St. István (or Vajk, his heathen name) is being baptized and accepting European Christianity in the year 1000. Not surprisingly, this was painted at the time of the Compromise of 1867, when Hungary was ceded authority within the Catholic Habsburg Empire. Again, the painter uses a historical story as a tip of the hat to contemporary events.

The rest of the collection is spread through several rooms across the atrium. Take a quick spin through these rooms: Begin by crossing the atrium and angling left, through the glass door at the top of the stairs. In a sharp contrast to what we’ve just seen, these Romantics—who painted mostly after the Great Compromise, when Hungary was feeling its oats—take an idealized view: pristine portraits of genteel city dwellers, bathing beauties with improbable proportions, and bucolic country folk. The best painting in here is straight ahead as you enter the room: the appealing Picnic in May by Pál Szinyei-Merse. While this scene is innocent today, the thought of men and women socializing freely was scandalous at the time.

Circling through these rooms, you’ll end up back on the other side of the atrium. Cross it once more, this time bearing right into the larger door. This section features a more sober view of the same reality that the Romantics shrouded in gauze. The genre paintings here show some of the challenges of both country and city life.

Exiting that section, turn right into an impressive collection of Realists. The biggest name here is Mihály Munkácsy, who lived in France alongside the big-name Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. Many of these paintings are gritty slices-of-life, showing the hardships of the poor; notice the sloppier, more Impressionistic brushstrokes. For example, in the second room, on the right, see the hazy, almost Turner-esque Dusty Road II.

In the third room, we take a break from Munkácsy with works by László Paál, who primarily painted murky nature scenes—sun-dappled paths through the forest, pondering the connection between man and nature. In the fourth room, on the left (by the door), Munkácsy captures the intensity of English poet John Milton dictating Paradise Lost to his daughters. (The wealthy and popular Munkácsy was also frequently hired to paint portraits.)

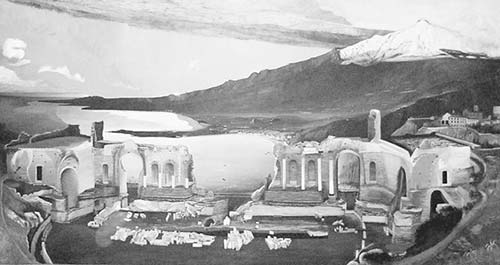

Backtrack to the atrium, then climb up one more flight of stairs. Straight ahead from the landing are three works by Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka, the “Hungarian Van Gogh” (for more on Csontváry, see here). Here you see a few of this well-traveled painter’s destinations: the giant canvas in the center depicts the theater at Taormina, Sicily; on the left are the waterfalls of Schaffhausen, Germany; and on the right is a cedar tree in Lebanon. Colorful, allegorical, and expressionistic, Csontváry is one of the most in-demand and expensive of Hungarian artists. If you enjoy Csontváry’s works and are headed to his hometown of Pécs, don’t miss his museum there (see here).

This good but stodgy museum celebrates the earlier grandeur of Castle Hill. It’s particularly strong in early history (prehistoric, ancient, medieval; for modern history, the National Museum is better).

Cost and Hours: 1,800 Ft, audio-guide-1,200 Ft, some good English descriptions posted; March-Oct Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, Nov-Feb Tue-Sun 10:00-16:00, closed Mon year-round; last entry 30 minutes before closing, district I, tel. 1/487-8800, www.btm.hu.

Visiting the Museum: On the ground floor (back-right corner, in a darkened room), stroll through the collection of 14th-century sculpture fragments. Many have strong Magyar features—notice that they look Central Asian (similar to Mongolians). In a small room at the end of this wing is a tapestry mixing the coats of arms of the Magyar Árpád dynasty (red-and-white stripes) with the French Anjou dynasty (fleur-de-lis)—the first two royal houses of Hungary—which was found balled up in a wad of mud.

One floor up, the good exhibit called “Budapest: Light and Shadow” traces a thousand years of the city’s history, with concise English descriptions. The top floor has artifacts of Budapest’s prehistoric residents. The cellar illustrates just how much this hill has changed over the centuries—and how dull today’s version is by comparison. You’ll wander through a maze of old palace parts, including the remains of an original Gothic chapel, a knights’ hall, and marble remnants (reliefs and fountains) of Matthias Corvinus’ lavish Renaissance palace.

The city has recently refurbished the long-decrepit gateway, gallery, garden, and staircase that stretches from the riverbank up to the Royal Palace. Originally designed by Miklós Ybl (of Opera House fame) in the 1870s, this Neo-Renaissance people zone evokes a more genteel time.

Cost and Hours: Garden free to enter and open long hours daily; exhibits have their own costs and hours. It’s along the Buda embankment, about halfway between the Ádám Clark tér and Döbrentei tér tram stops, at Ybl Miklós tér.

Visiting the Park and Staircase: Walk through the ornate archway (past the bubbling fountain) and climb up the stairs to a cozy plateau with lush, flowery parklands ringed by monumental buildings. Originally, this “Castle Garden Bazaar” was mostly a shopping zone; in its next iteration, the buildings will house cultural institutions, including the National Dance Theater, a convention center, and exhibition space for temporary exhibits (and an exhibit on the architect Ybl and his works). The garden area is divided in half by a long, stately staircase and covered escalator, offering a quick ascent partway up Castle Hill. From the top of the escalator, a series of two elevators bring visitors the rest of the way up to the Royal Palace. Alternatively, you can hike up a long but scenic switchback trail along the ramparts to reach the palace. As this area is still under redevelopment, check www.varkertbazar.hu for the latest.

Arguably Budapest’s finest church inside and out, this historic house of worship—with a frilly Neo-Gothic spire and gilded Hungarian historical motifs slathered on every interior wall—is Castle Hill’s best sight. From the humble Loreto Chapel (with a tranquil statue of the Virgin that helped defeat the Ottomans), to altars devoted to top Hungarian kings, to a replica of the crown of Hungary, every inch of the church oozes history.

Cost and Hours: 1,200 Ft, includes Museum of Ecclesiastical Art (unless closed for renovation), audioguide may be available, Mon-Fri 9:00-17:00—possibly also open 19:00-20:00 in summer, Sat 9:00-13:00, Sun 13:00-17:00, Szentháromság tér 2, district I, tel. 1/488-7716, www.matyas-templom.hu.

For a self-guided tour of the Matthias Church,  see the Castle Hill Walk chapter.

see the Castle Hill Walk chapter.

Seven pointy domes and a double-decker rampart run along the cliff in front of Matthias Church. Evoking the original seven Magyar tribes, and built for the millennial celebration of their arrival, the Fishermen’s Bastion is one of Budapest’s top landmarks. This fanciful structure adorns Castle Hill like a decorative frieze or wedding-cake flowers. While some suckers pay for the views from here, parts of the rampart are free and always open. Or you can enjoy virtually the same view through the windows next to the bastion café for free.

Cost and Hours: 700 Ft, buy ticket at ticket office along the park wall across the square from Matthias Church, daily mid-March-mid-Oct 9:00-19:30; after closing time and off-season, no tickets are sold, but bastion is open and free to enter; Szentháromság tér 5, district I.

Standing like a lonely afterthought at the northern tip of Castle Hill, St. Mary Magdalene was the crosstown rival of the Matthias Church. After the hill was recaptured from the Ottomans, only one church was needed, so St. Mary sat in ruins. But ultimately they rebuilt the church tower—which today evokes the rich but now-missing cultural tapestry that was once draped over this hill (free, always viewable).

This fine museum explains various Hungarian military actions through history in painstaking detail. Watch military uniforms and weaponry evolve from the time of Árpád to today. With enough old uniforms and flags to keep an army-surplus store in stock for a decade, but limited English information, this place is of most interest to military and history buffs.

Cost and Hours: 1,400 Ft, April-Sept Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, Oct-March Tue-Sun 10:00-16:00, closed Mon year-round, Tóth Árpád sétány 40, district I, tel. 1/325-1600.

The hill is honeycombed with caves and passages, which are accessible to tourists in two different locations: The better option (Hospital in the Rock) comes with a fascinating tour illustrating how the caves were in active use during World War II and the Cold War; the Labyrinth offers a quicker visit with only a lightweight, quasi-historical exhibit.

Bring your Castle Hill visit into modern times with this engaging tour. Sprawling beneath Castle Hill is a 25,000-square-foot labyrinthine network of hospital and fallout-shelter corridors built during the mid-20th century. (Hidden access points are scattered throughout the tourist zone, aboveground.) After decades in mothballs, the complex opened its doors to tourists a few years ago. While pricey, this visit is a must for doctors, nurses, and World War II buffs. I enjoy this as a lively interactive experience to balance out an otherwise sedate Castle Hill visit.

Cost and Hours: 3,600 Ft for required one-hour tour, 10 percent discount with Matthias Church ticket, additional discount if you’re in the medical profession and can show your ID, daily 10:00-20:00, English tours at the top of each hour, last tour departs at 19:00, gift shop like an army-surplus store, Lovas utca 4C, district I, mobile 0670-701-0101, www.sziklakorhaz.eu/en.

Getting There: To find the hospital, stand with your back to Matthias Church and the Fishermen’s Bastion. Walk straight past the plague column and down the little street (Szentháromság utca), then go down the covered steps at the wall. At the bottom of the stairs, turn right on Lovas utca, and walk 50 yards to the well-marked bunker entrance.

Background: At the outbreak of World War II, in 1939, the Hungarian government began building a secret emergency surgical hospital here in the heart of Budapest. When the war finally reached Hungary, in 1945, the hospital was in heavy use. While designed for 200 patients, eventually it held more than triple that number. Later, the forgotten hospital was used for two months to care for those injured in the 1956 Uprising. Then, as nuclear paranoia grew intense in the late 1950s and early 1960s, it was expanded to include a giant bomb shelter and potential post-nuclear-holocaust hospital.

Visiting the Hospital and Bunker: First you’ll watch a 10-minute movie (with English subtitles) about the history of the place. Then, on the tour, your guide leads you through the tunnels to see room after room of perfectly preserved WWII and 1960s-era medical supplies and equipment, most still in working order. More than 200 wax figures engagingly bring the various hospital rooms to life: giant sick ward, operating room, and so on. On your way to the fallout shelter, you’ll pass the decontamination showers, and see primitive radiation detectors and communist propaganda directing comrades how to save themselves in case of capitalist bombs or gas attacks. In the bunker, you’ll also tour the various mechanical rooms that provided water and ventilation to this sprawling underground city.

Armchair spelunkers can explore these dank and hazy caverns, with some wax figures in period costume, sparse historical information in English, a few actual stone artifacts, and a hokey Dracula exhibit (based on likely true notions that the “real” Dracula, the Transylvanian Duke Vlad Ţepeş, was briefly imprisoned under Buda Castle). As this is indeed a labyrinth, expect to get lost—but don’t worry; eventually you’ll find your way out. After 18:00, they turn the lights out and give everyone gas lanterns. The exhibit loses something in the dark, but it’s nicely spooky and a fun chance to startle amorous Hungarian teens—or be startled by mischievous ones. Even so, this hokey tourist trap pales in comparison with the other “underground” option.

Cost and Hours: 2,000 Ft, daily 10:00-19:30, last entry at 19:00, entrance between Royal Palace and Matthias Church at Úri utca 9, district I, tel. 1/212-0207, www.labirintus.com.

The hill rising from the Danube just downriver from the castle is Gellért Hill. When King István converted Hungary to Christianity in the year 1000, he brought in Bishop Gellért, a monk from Venice, to tutor his son. But some rebellious Magyars had other ideas. They put the bishop in a barrel, drove long nails in from the outside, and rolled him down this hill...tenderizing him to death. Gellért became the patron saint of Budapest and gave his name to the hill that killed him. Today the hill is a fine place to commune with nature on a hike or jog, followed by a restorative splash in its namesake baths. The following sights are listed roughly from north to south.

The north slope of Gellért Hill (facing Castle Hill) is good for a low-impact hike. You’ll see many monuments, most notably the big memorial to Bishop Gellért himself (you can’t miss him, standing in a grand colonnade, as you cross the Elisabeth Bridge on Hegyalja út). A bit farther up, seek out a newer monument to the world’s great philosophers—Eastern, Western, and in between—from Gandhi to Plato to Jesus. Nearby is a scenic overlook with a king and a queen holding hands on either side of the Danube.

This strategic, hill-capping fortress was built by the Habsburgs after the 1848 Revolution to keep an eye on their Hungarian subjects. There’s not much to do up here (no museum or exhibits), but it’s a good destination for an uphill hike, and provides the best panoramic view over all of Budapest.

The hill is crowned by the Liberation Monument, featuring a woman holding aloft a palm branch. Locals call it “the lady with the big fish” or “the great bottle opener.” A heroic Soviet soldier, who once inspired the workers with a huge red star from the base of the monument, is now in Memento Park (see here).

Getting There: It’s a steep hike up from the river to the Citadella. Bus #27 cuts some time off the trip, taking you up to the Búsuló Juhász stop (from which it’s still an uphill hike to the fortress). You can catch bus #27 from either side of Gellért Hill. From the southern edge of the hill, catch this bus at the Móricz Zsigmond körtér stop (easy to reach: ride trams #19 or #41 south from anywhere along Buda’s Danube embankment, or trams #47 or #49 from Pest’s Small Boulevard ring road; you can also catch any of these trams at Gellért tér, in front of the Gellért Hotel). Alternatively, on the northern edge of the hill, catch bus #27 along the busy highway (Hegyalja út) that bisects Buda, at the intersection with Sánc utca (from central Pest, you can get to this stop on bus #178 from Astoria or Ferenciek tere).

Hidden in the hillside on the south end of the hill (across the street from Gellért Hotel) is Budapest’s atmospheric cave church—burrowed right into the rock face. The communists bricked up this church when they came to power, but now it’s open for visitors once again (500 Ft, unpredictable hours, closed to sightseers during frequent services). The little house at the foot of the hill (with the pointy turret) is where the monks who care for this church reside.

Located at the famous and once-exclusive Gellért Hotel, right at the Buda end of the Liberty Bridge, this elegant bath complex has long been the city’s top choice for a swanky, hedonistic soak. It’s also awash in tourists, and the Széchenyi Baths beat it out for pure fun...but the Gellért Baths’ mysterious thermal spa rooms, and its giddy outdoor wave pool, make it an enticing thermal bath option.

Cost and Hours: 4,900 Ft for a locker, 400 Ft more for a personal changing cabin, cheaper after 17:00; open daily 6:00-20:00, last entry one hour before closing; Kelenhegyi út 4, district XI, M4: Gellért tér, tel. 1/466-6166, ext. 165, www.gellertbath.com.

See the Thermal Baths chapter.

See the Thermal Baths chapter.

Along the Danube toward Castle Hill from Gellért Baths, Rudas (ROO-dawsh) offers Budapest’s most old-fashioned, Turkish-style bathing experience. The historic main pool of the thermal bath section sits under a 500-year-old Ottoman dome. Bathers move from pool to pool to tweak their body temperature. On weekdays, it’s a nude, gender-segregated experience, while it becomes more accessible (and mixed) on weekends, when men and women put on swimsuits and mingle beneath that historic dome. Rudas also has a ho-hum swimming pool, and a state-of-the-art “wellness” section, with a variety of modern massage pools and an inviting hot tub/sun deck on the roof with a stunning Budapest panorama (these two areas are mixed-gender every day).

Cost and Hours: The three parts are covered by separate tickets: thermal baths-3,000 Ft, wellness center-2,900 Ft, combo-ticket for all three-4,500 Ft (or 5,500 Ft on weekends); daily 6:00-20:00, last entry one hour before closing; open for nighttime bathing with nightclub ambience Fri-Sat 22:00-late (4,400 Ft); wellness and swimming pool areas mixed-gender and clothed at all times; thermal baths men-only Mon and Wed-Fri, women-only Tue, mixed Sat-Sun and during nighttime bathing; Döbrentei tér 9, district I, tel. 1/375-8373, www.rudasbaths.com.

See the Thermal Baths chapter.

See the Thermal Baths chapter.

There’s not much of interest to tourists in Buda beyond Castle and Gellért Hills.

The Víziváros area, or “Water Town,” is squeezed between Castle Hill and the Danube. While it’s a useful home base for sleeping and eating (see those chapters for details), and home to the Budai Vigadó concert venue (see the Entertainment in Budapest chapter), there’s little in the way of sightseeing. The riverfront Batthyány tér area, at the northern edge of Víziváros, is a hub both for transportation (M2/red Metró line, HÉV suburban railway to Óbuda and Szentendre, and embankment trams) and for shopping and dining.

To the north of Castle Hill is Széll Kálmán tér, a transportation hub (for the M2/red Metró line, several trams, and buses #16, #16A, and #116 to Castle Hill) and shopping center (featuring the giant Mammut supermall, and many smaller shops that cling to it like barnacles to a boat). This unpretentious zone, while light on sightseeing, offers a chance to commune with workaday Budapest. Its one attraction is Millenáris Park, an inviting play zone for adults and kids that combines grassy fields and modern buildings. Though not worth going out of your way for, this park might be worth a stroll if the weather’s nice and you’re exploring the neighborhood (a long block behind Mammut mall).

Rózsadomb (“Rose Hill”), rising just north of Széll Kálmán tér, was so named for the rose garden planted on its slopes by a Turkish official 400 years ago. Today it’s an upscale residential zone.

To the south, the district called the Tabán—roughly between Castle Hill and Gellért Hill—was once a colorful, ramshackle neighborhood of sailor pubs and brothels. After being virtually wiped out in World War II, now it’s home to parks and a dull residential district.

Beyond riverfront Buda, the terrain becomes hilly. This area—the Buda Hills—is a pleasant getaway for a hike or stroll through wooded terrain, but still close to the city. One enjoyable way to explore these hills is by hopping a ride on the Children’s Railway (see the Budapest with Children chapter).

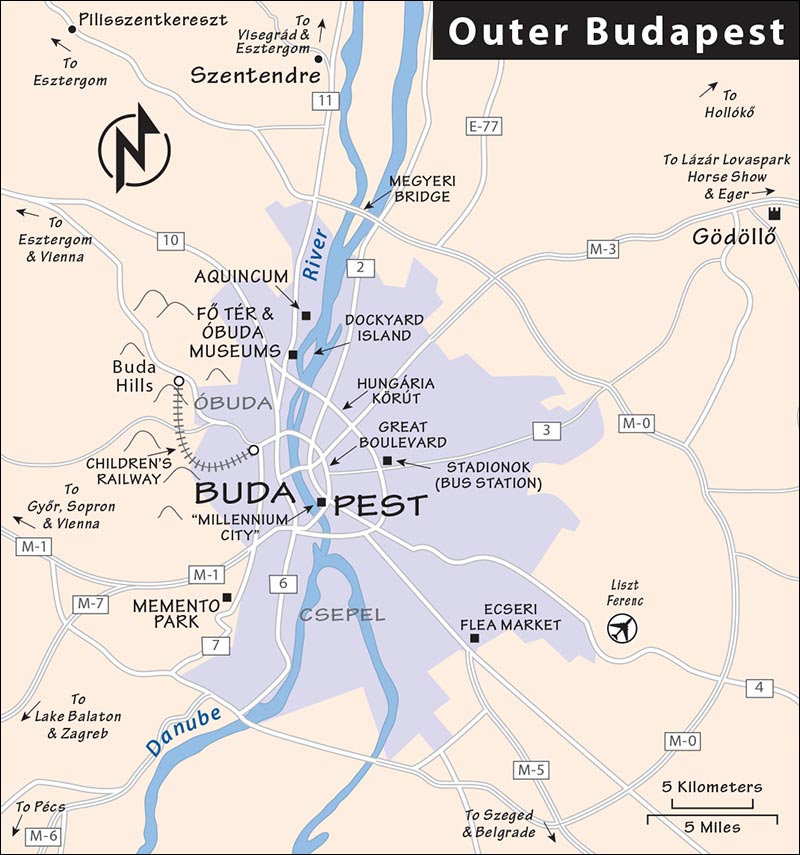

Two other major attractions—the part of town called Óbuda (“Old Buda”) and Memento Park—are on the Buda side of the river but away from the center, and described in the following sections.

The following sights, while technically within Budapest, take a little more time to reach.

Budapest was originally three cities: Buda, Pest, and Óbuda. Óbuda (“Old Buda”) is the oldest of the three—the first known residents of the region (Celts) settled here, and today it’s still littered with ruins from the next occupants (Romans). Despite all the history, the district ranks relatively low on the list of Budapest’s sightseeing priorities: Aside from a charming small-town ambience on its main square, it offers a pair of good museums on two important 20th-century Hungarian artists, and—a short train ride away—some Roman ruins.

Getting There: To reach the first three sights listed here, go to Batthyány tér in Buda (M2/red Metró line) and catch the HÉV suburban train (H5/purple line) north to the Szentlélek tér stop. The Vasarely Museum is 50 yards from the station (exit straight ahead, away from the river; it’s on the right, behind the bus stops). The town square is 100 yards beyond that (bear right around the corner), and 200 yards later (turn left at the ladies with the umbrellas), you’ll find the Imre Varga Collection. Aquincum is three stops farther north on the HÉV line.

This museum features two floors of eye-popping, colorful paintings by Victor Vasarely (1906-1997), the founder of Op Art. If you’re not going to Vasarely’s hometown of Pécs, which has an even better museum of his works (see here), this place gives you a good taste. The exhibition—displayed in a large, white hall with each piece labeled in English—follows his artistic evolution from his youth as a graphic designer to the playful optical illusions he was most famous for. You’ll find most of these trademark works (as well as temporary exhibits of other artists) upstairs. Sit on a comfy bench and stare into Vasarely’s mind-bending world. Let yourself get a little woozy. Think of how this style combines right-brained abstraction with an almost rigidly left-brained, geometrical approach. It makes my brain hurt (or maybe it’s just all the wavy lines). Vasarely and the movement he pioneered helped to inspire the trippy styles of the 1960s. If the art gets you pondering Rubik’s Cube, it will come as no surprise that Ernő Rubik was a professor of mathematics here in Budapest.

Cost and Hours: 800 Ft, Tue-Sun 10:00-17:30, closed Mon, Szentlélek tér 6, district III, tel. 1/388-7551, www.vasarely.hu. The museum is immediately on the right as you leave the Szentlélek tér HÉV station.

If you keep going past the Vasarely Museum and turn right, you enter Óbuda’s cute Main Square. The big, yellow building was the Óbuda Town Hall when this was its own city. Today it’s still the office of the district mayor. While still well within the city limits of Budapest, this charming square feels like its own small town.

To the right of the Town Hall is a whimsical, much-photographed statue of women with umbrellas. Replicas of this sculpture, by local artist Imre Varga, decorate the gardens of wealthy summer homes on Lake Balaton. Varga created many of Budapest’s distinctive monuments, including the Tree of Life behind the Great Synagogue and a major work that’s on display at Memento Park. His museum is just down the street (turn left at the umbrella ladies).

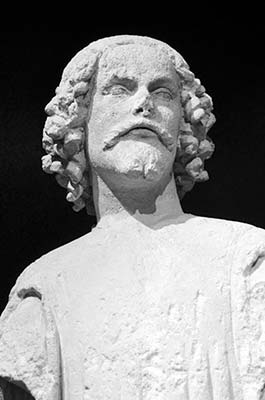

Imre Varga, who worked from the 1950s through the 2000s, is one of Hungary’s most prominent artists, and probably its single best sculptor. This humble museum—crammed with his works (originals, as well as smaller replicas of Varga statues you’ll see all over Hungary), and with a fine sculpture garden out back—offers a good introduction to the man’s substantial talent. Working mostly with steel, his pieces can appear rough and tangled at times, but are always evocative and lifelike. Unfortunately, English information is virtually nonexistent here.

Cost and Hours: 800 Ft, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon, Laktanya utca 7, district III, Szentlélek tér HÉV station, tel. 1/250-0274, www.budapestgaleria.hu.

Visiting the Museum: The first room holds a replica of a sculpture of St. István approaching the Virgin Mary, the original of which is in the Vatican. The next room has several small-scale copies of famous Varga works from around the country, including some you might recognize from Budapest (such as the Tree of Life from behind the Great Synagogue).

Pause at the statue with the headless, saluting soldier wearing medals. Through the communist times, there were three types of artists: banned, tolerated, and supported. Varga was tolerated, and works like this subtly commented on life under communism. In fact, the medallions nailed to the figure’s chest were Varga’s own, from his pre-communist military service. Anyone with such medallions was persecuted by communists in the 1950s...so Varga disposed of his this way.

Nearby is the exit to the garden out back, with a smattering of life-size portraits (including three prostitutes leaning against a wall, illustrating the passing of time). The rest of the museum is predominantly filled with portraits (mostly busts) of various important Hungarians. You’ll see variations on certain themes that intrigued Varga, including a reclining ballerina.

Long before Magyars laid eyes on the Danube, Óbuda was the Roman city of Aquincum. Here you can explore the remains of the 2,000-year-old Roman town and amphitheater. The museum is proud of its centerpiece, a water organ.

Cost and Hours: 1,600 Ft, grounds open April-Oct Tue-Sun 9:00-18:00, Nov-March Tue-Sun 9:00-16:00, exhibitions open one hour later, closed Mon year-round, Szentendrei út 139, district III, HÉV north to Aquincum stop, tel. 1/250-1650, www.aquincum.hu.

Getting There: From the HÉV stop, cross the busy road and turn to the right. Go through the railway underpass, and you’ll see the ruins ahead and on the left as you emerge.

Little remains of the communist era in Budapest. To sample those drab and surreal times, head to this motley collection of statues, which seem to be preaching their Marxist ideology to each other in an open field on the outskirts of town. You’ll see the great figures of the Soviet Bloc, both international (Lenin, Marx, and Engels) and Hungarian (local bigwig Béla Kun) as well as gigantic, stoic figures representing Soviet ideals. This stiff dose of Socialist Realist art, while time-consuming to reach, is rewarding for those curious for a taste of history that most Hungarians would rather forget.

Cost and Hours: 1,500 Ft, daily 10:00-sunset, six miles southwest of city center at the corner of Balatoni út and Szabadka út, district XXII, tel. 1/424-7500, www.mementopark.hu.

Getting There: The park runs a handy direct bus from Deák tér in downtown Pest to the park (April-Oct daily at 11:00, Nov-March Sat-Mon at 11:00—no bus Tue-Fri, round-trip takes 2.5 hours total, including a 1.5-hour visit to the park, 4,900-Ft round-trip includes park entry, book online for discount: www.mementopark.hu).

The public transport option requires a transfer: Ride the Metró’s M4/green line to the end of the line at Kelenföld. Head up to street level and catch bus #101, which takes you to Memento Park in about 15 minutes (second stop, runs every 10 minutes—but only on weekdays). On weekends, when bus #101 doesn’t run, take bus #150, which takes longer (2/hour, about 25 minutes). On either bus, be sure the driver knows where you want to get off.

See the Memento Park Tour chapter.

See the Memento Park Tour chapter.

For information on the village of Szentendre, the Royal Palace at Gödöllő, and the engaging horse shows at Lázár Lovaspark (all just outside the city limits), as well as some places farther afield (the royal castles at Visegrád, the great church at Esztergom, and the folk village of Hollókő), see the Day Trips from Budapest chapter.