What tests and workups would you recommend to figure out why I haven’t conceived yet?

What tests and workups would you recommend to figure out why I haven’t conceived yet?YOU’VE BEEN WORKING HARD AT TTC. You can pinpoint ovulation with your eyes closed, you’ve got your sex timing and positioning down to a science. But things (as in sperm and egg) are just not clicking yet and you’re still not pregnant. Maybe you (and your doctor) have found a reason for your fertility frustrations. Maybe there’s no known cause. Whatever the case, you’re probably wondering: How long should we keep trying on our own? Is it time to consider seeing an infertility specialist? And if we do need a little help, what are our options?

If your plans to start a family are going nowhere fast, you might be thinking about seeing a fertility specialist. But are you getting worried too soon? Should you just continue trying for a few more months? Or should you get started with a fertility workup just in case? Read on for answers to these (and other) questions.

“We’ve been trying to conceive for six months already. Is it time to find a fertility specialist?”

Considering how fundamental a human function it is (there couldn’t be humans without it), conception isn’t as easy to achieve as you’d think. Sure, it can happen overnight—or even after one early morning quickie—but it usually takes much longer. In fact, under the best of circumstances, a couple with no known fertility issues has only a 20 to 25 percent chance of conceiving in a given menstrual cycle—which means they have a 75 to 80 percent chance of coming up empty at the end of any given month. So no need to jump to any conclusions about your fertility—or to jump in your car and head for the nearest fertility clinic—if sperm and egg don’t meet up right away.

That said, if you’ve reached the 6-month mark of active trying (following all the recommended baby-making guidelines) without accomplishing your mission, you might want to start thinking about next steps—though it might be too early to actually start taking those steps right now. Here’s the usual fertility rule of thumb when it comes to when to seek help: If you and your spouse have no known reproductive problems and you’re under 35, consider trying on your own for a year. If you’re older than 35 and don’t have any known fertility issues, help is usually suggested after 3 to 6 months of trying without success, though you can seek it earlier if you’re concerned about running out of time. If you are 38 or older, many doctors recommend beginning those workups after just 3 months. And if you’re over 40 or have a history of medical problems or a family history of infertility or any other factors that might impede fertility, it makes sense to arm yourself with the right help right from the start, to give your more challenging campaign the best chance for success.

But before you start Googling fertility specialists in your area, pick up the phone and make an appointment to see your regular ob-gyn. Find out if he or she can handle your fertility needs (at least any initial workup) or whether you’ll likely need a specialist on board, too. Even if your regular practitioner would be out of his or her league with your particular fertility scenario—and suggests that a fertility specialist be called in to consult or take over your diagnosis and treatment—he or she should still be on your team.

Keep in mind that you may not nab an appointment with your ob-gyn right away, and that you’ll almost certainly have a wait before getting on the books with a fertility specialist, so plan ahead (in other words, call for that appointment a month or two before your “cutoff” date). The worst (or rather the best) that can happen? You make the appointment, and then have to cancel—and schedule a prenatal visit instead—because you’re pregnant!

“I don’t know the first place to start with finding a fertility specialist—all I know is we’re having trouble conceiving and we have no clue why.”

If sperm and egg aren’t meeting on their own, which type of practitioner would be the best matchmaker? Your ob-gyn is a good place to start because he or she can begin a basic fertility workup and either treat your fertility issues on his or her own or send you for a more complete workup and more advanced treatment with a reproductive endocrinologist (RE)—a fancy way of saying “fertility specialist.”

The good news is that in most cases, fertility difficulties can be resolved by an ob-gyn without an extensive fertility evaluation or treatment by an infertility specialist. And even if you’re sent to an RE, it doesn’t mean you’re starting down the path of high-tech (and expensive) fertility treatments. In fact, most couples can be treated with simple medications and/or minor surgery and possibly intrauterine insemination (IUI) and never even have to attempt the more involved in vitro fertilization (IVF).

Whichever type of doctor you’re seeing (or even if you’re seeing more than one), come prepared with a list of questions. Knowledge is power, and the more you know about tests and treatment options you might be facing, the easier they’ll be to face. Here are some suggestions for questions you may want to ask your ob-gyn or RE:

What tests and workups would you recommend to figure out why I haven’t conceived yet?

What tests and workups would you recommend to figure out why I haven’t conceived yet?

Should my spouse be tested? Should he be tested first or at the same time?

Should my spouse be tested? Should he be tested first or at the same time?

What are the tests for male fertility?

What are the tests for male fertility?

How much will the tests cost?

How much will the tests cost?

How long will it take to diagnose a problem if there is one?

How long will it take to diagnose a problem if there is one?

Based on the results of those tests, what are my treatment options?

Based on the results of those tests, what are my treatment options?

How much do the treatments cost?

How much do the treatments cost?

How long do we try one treatment option before we move on to another?

How long do we try one treatment option before we move on to another?

What is your success rate with fertility treatments?

What is your success rate with fertility treatments?

Are there any side effects to the fertility treatments you’re suggesting?

Are there any side effects to the fertility treatments you’re suggesting?

“What’s involved in a fertility workup? And do we both get worked up at the same time?”

Trying to find out why the seemingly simple process of reproduction isn’t working can be a little complicated—especially for women (sorry). In fact, the workup for men is so much easier (as is the treatment of any diagnosed fertility issue), that it’s sometimes recommended that workups start with him. Talk to your practitioner about the best way to proceed, and whether you should be worked up one at a time or in tandem. Either way, here’s what you can typically expect from your fertility workups.

For him. The male fertility exam includes:

A general physical, a thorough examination of the testes, scrotum, and penis, and perhaps a culture from the opening of the penis to rule out infection (don’t worry—it’s quick, easy, and usually painless). Since one possible cause of fertility difficulties is varicoceles in the scrotal sac (see page 148), the doctor will carefully examine the testicles to make sure everything checks out fine in that department.

A general physical, a thorough examination of the testes, scrotum, and penis, and perhaps a culture from the opening of the penis to rule out infection (don’t worry—it’s quick, easy, and usually painless). Since one possible cause of fertility difficulties is varicoceles in the scrotal sac (see page 148), the doctor will carefully examine the testicles to make sure everything checks out fine in that department.

A semen analysis. While it’s inherently unfair that the female workup involves (as you’ll read later) needles and ultrasounds, and the male workup involves a stack of porn and one of his favorite pastimes since high school, a semen analysis is still a crucial first step in figuring out where the fertility problem might be coming from. A sperm analysis checks the quantity and quality of sperm in the ejaculate (there should be more than 20 million sperm per milliliter of semen and more than 50 percent of them should be moving). The sperm analysis may also look at sperm DNA fragmentation (in other words, sperm that is “broken”). For optimum fertility, no more than 30 percent of sperm DNA should be fragmented. If the numbers come back low, the test is repeated (sperm count varies from ejaculate to ejaculate).

A semen analysis. While it’s inherently unfair that the female workup involves (as you’ll read later) needles and ultrasounds, and the male workup involves a stack of porn and one of his favorite pastimes since high school, a semen analysis is still a crucial first step in figuring out where the fertility problem might be coming from. A sperm analysis checks the quantity and quality of sperm in the ejaculate (there should be more than 20 million sperm per milliliter of semen and more than 50 percent of them should be moving). The sperm analysis may also look at sperm DNA fragmentation (in other words, sperm that is “broken”). For optimum fertility, no more than 30 percent of sperm DNA should be fragmented. If the numbers come back low, the test is repeated (sperm count varies from ejaculate to ejaculate).

He’ll likely be told to avoid ejaculation for 2 to 3 days before the semen analysis so that his sperm count will be at its highest. If multiple samples will be necessary, it’s best to obtain them using the same spacing (in other words, if his first sample was produced 3 days after his last ejaculation, the next should also be produced after a 3-day wait). To produce the semen sample, he’ll be asked to ejaculate into a clean sample cup—either in a private room in the doctor’s office or, if you live close enough to the office, at home just before bringing it to the office for testing. If it’s possible to produce the sample at home, be sure to get it to the office within an hour, carrying it in a bag or coat pocket (it shouldn’t get too hot or cold—room temperature is best). If the thought of masturbating into a cup isn’t appealing to your guy, ask the doctor if you can use a special condom during intercourse to collect the sample instead. That sample, too, would have to be rushed to the lab (so much for the post-coital cuddling).

For her. The female fertility workup is a little more involved than the man’s. It can include:

A physical exam and a comprehensive pelvic exam if one was not done recently (during a preconception visit). A Pap smear will also be done to rule out abnormal cervical cells or infections.

A physical exam and a comprehensive pelvic exam if one was not done recently (during a preconception visit). A Pap smear will also be done to rule out abnormal cervical cells or infections.

A blood test to determine levels of reproductive hormones. Usually taken on day 3 of your cycle, the test will check FSH levels to gauge ovarian reserve (see page 98) and estrogen (abnormally high levels on day 3 may indicate ovarian cysts or diminished ovarian reserve). Another blood test taken after ovulation will test for progesterone to confirm that ovulation has taken place. Other hormone levels (such as thyroid and prolactin) may also be checked.

A blood test to determine levels of reproductive hormones. Usually taken on day 3 of your cycle, the test will check FSH levels to gauge ovarian reserve (see page 98) and estrogen (abnormally high levels on day 3 may indicate ovarian cysts or diminished ovarian reserve). Another blood test taken after ovulation will test for progesterone to confirm that ovulation has taken place. Other hormone levels (such as thyroid and prolactin) may also be checked.

Pelvic ultrasound (usually performed vaginally) to determine the number of egg follicles in the ovaries and how they are growing, as well as to visualize the uterus and cervix.

Pelvic ultrasound (usually performed vaginally) to determine the number of egg follicles in the ovaries and how they are growing, as well as to visualize the uterus and cervix.

A post-coital test (the name says it all) performed a few hours after intercourse. The test, which isn’t done routinely anymore by most doctors, uses a cervical mucus swab to look at how his sperm swims in your cervical fluid. It’s done 1 to 2 days before ovulation. Within 2 to 8 hours after you have sex with your spouse (in private at home), you’ll go to the doctor’s office where the test (similar to a Pap smear) will be done.

A post-coital test (the name says it all) performed a few hours after intercourse. The test, which isn’t done routinely anymore by most doctors, uses a cervical mucus swab to look at how his sperm swims in your cervical fluid. It’s done 1 to 2 days before ovulation. Within 2 to 8 hours after you have sex with your spouse (in private at home), you’ll go to the doctor’s office where the test (similar to a Pap smear) will be done.

A hysterosalpingogram (HSG)—an assessment of the uterus and fallopian tubes using X-ray imaging and dye (for contrast) to make sure there are no blockages in the fallopian tubes or scarring in the fallopian tubes or uterus that might be preventing conception. Alternatively, your doctor may perform a sonohystogram, an essentially painless test where saline is infused into the uterus through the cervix while the uterus is visualized on ultrasound.

A hysterosalpingogram (HSG)—an assessment of the uterus and fallopian tubes using X-ray imaging and dye (for contrast) to make sure there are no blockages in the fallopian tubes or scarring in the fallopian tubes or uterus that might be preventing conception. Alternatively, your doctor may perform a sonohystogram, an essentially painless test where saline is infused into the uterus through the cervix while the uterus is visualized on ultrasound.

Sound like you (and your doctor) have your work cut out for you? You definitely do. Be prepared for the workup to take 6 to 8 weeks before all the tests are completed and the results compiled and evaluated. Once the results are back in, your doctor will discuss with you the best plan of action to help you conceive.

So you’ve both been worked over, maybe more than once. You’ve done plenty of waiting—and more waiting—for the results. But it’s all worth it, you figure, because finally, you’ll have the diagnosis that will solve the mystery of your infertility, and with it, the treatment that will bring you one step closer to filling your belly—and, ultimately, your arms—with the baby you’ve been hoping for.

Sometimes, it is as simple as that—diagnosing is easy and treatment an easy fix. A correctable condition is discovered, and all that’s needed is minor surgery to remove some scarring or a cyst, or some thyroid replacement therapy to jump-start your cycles.

But that discovery isn’t always easy, or even possible to make. Often, not even that exhaustive—and exhausting—full battery of tests and screenings (and needle pokes and embarrassing sperm collections) uncovers the exact cause of a fertility problem. Many couples end up with the finding “unexplained infertility”—and isn’t that where you started in the first place, before all the testing began?

Fortunately, in most cases you don’t need a definitive diagnosis to treat a fertility issue. No matter what the cause—and even if there is no known cause—there’s usually at least one treatment option for every couple that’s facing a fertility challenge. The following is an overview of the most common treatments—including, fertility fingers crossed and double-crossed, the one with your beautiful baby-to-be’s name on it.

While surgery to correct fertility problems used to be the first line of defense in treating infertile couples, doctors today are depending more and more on assisted reproductive techniques (ART; see more in this chapter) instead of surgery. Still, depending on what’s causing your infertility, your doctor might suggest certain surgical procedures to help get you closer to conception.

For instance, if tests find that you have anatomical problems in your uterus, cervix, or vagina (and these problems are preventing you from conceiving or maintaining a pregnancy), surgery can be a quick way to fix the problem and enable you to conceive a baby on your own. If you have scar tissue in your uterus or fallopian tubes, surgery can clear the path for sperm and egg to meet. Tumors, cysts, fibroids, and endometrial lesions can also be removed surgically.

Often, surgery is performed with a hysteroscope, an instrument inserted through the cervix and into the uterus that visualizes the uterine cavity. If any abnormalities are found (such as fibroids, scar tissue, or a septum—when tissue divides the uterus in two), additional instruments can be inserted through the hysteroscope to remove or repair the problems. Another procedure, known as laparoscopy, is used to view all the pelvic organs and, if necessary, to remove endometrial lesions, ovarian cysts, scar tissue, or fibroids. Your doctor inserts a long viewing tube (or laparoscope) through an incision in your belly button. To perform the surgery, he or she inserts the necessary surgical tools through small incisions near your bikini line. Laparotomy microsurgery (in which the surgeon looks through magnifying glasses while removing scar tissue or endometrial lesions) is another option, but is used less often. For women suffering with fibroids, the surgery of choice is often a myomectomy using laparoscopy (see page 139). Most of the time, surgery is done as an outpatient procedure (you’ll be able to go home only a few hours after the surgery is complete) and the recovery is usually quick.

What if your tubes are tied—but now you’re wishing they weren’t (so you could pick up your nest filling where you last left off)? Luckily, those tied tubes won’t likely stand between you and your renewed baby dreams. One option is to bypass the tubes altogether, and go directly to IVF. Because fertilization takes place outside of your body with IVF, and the resulting embryo (or embryos) is placed directly into destination uterus, the fallopian tubes (the tubes that are “tied”) aren’t needed.

If you’d like to try to conceive the old-fashioned way, you may be able to have surgery to reverse your tubal ligation (depending on whether your fallopian tubes were cut, tied, cauterized, or nonsurgically blocked). Tubal reversal surgery is most commonly performed through an incision in the abdomen (though some doctors perform it laparoscopically). The surgery is not a walk in the park, unfortunately (you’ll need to stay in the hospital for a few days) and recovery can take a few weeks. Still, it could definitely prove worthwhile—there is a 75 percent pregnancy success rate (for women under 35 with no other fertility problems) within a year postsurgery (though the procedure slightly elevates the risk of ectopic pregnancy).

Before you go the surgery route, however, you’ll want to make sure your spouse’s sperm is top notch (it would be a waste to have the tubal reversal only to find out later that his sperm count is low and IVF is your only conception option). Your doctor will also want to verify (through a hysterosalpingogram) that your remaining tubes are long enough to be reattached successfully (the shorter they are, the lower the chances for a pregnancy), and that you have no other fertility issues.

If your fertility workup shows you’re not ovulating regularly, you’ve got a lot of company. About a third of all women struggling to get pregnant have ovulation issues, sometimes explained, often not. But for many, there’s an easy fix in a little pill. Clomiphene citrate, aka Clomid or Serophene, stimulates your ovaries to release eggs and corrects irregular ovulation. You’ll begin by taking 50 mg of Clomid on the second or third (or sometimes fifth) day of your period for 5 days. If you don’t begin to ovulate right away, the dose will be increased by 50 mg per day each month up to 150 mg. Once the drug is working and you’ve begun to ovulate, you’ll likely be kept on Clomid for 3 to 6 months. If you haven’t conceived by the sixth month on Clomid, you’ll move on to other medications and/or assisted fertility techniques.

Clomid works by making your body think estrogen levels are low (who said you can’t fool Mother Nature?). When your body finds itself low on estrogen, it compensates by producing more FSH and LH, stimulating the development of the follicle (and egg) and causing ovulation to occur. After that, it’s a sort of domino effect—but the good kind (the kind that’s meant to knock you up, not knock you down). The development of the eggs kicks up your estrogen, which in turn helps produce better quality cervical mucus (for most, but not all, women; some women find their CM becomes dry and sticky while on Clomid), making it easier for those sperm to hitch a ride toward the egg or eggs now being released. Higher levels of estrogen also beef up your uterine lining, and a thicker lining makes a much more hospitable implantation site for a fertilized egg—and one in which it’ll be easier to stay implanted. And there’s more to this chain of happy events: More eggs means more progesterone (produced by the corpus luteum that’s left behind after an egg is released). More progesterone also helps build a strong lining for that egg to latch on to, plus helps maintain a new pregnancy. Best of all, by the time fertilization occurs, Clomid is out of your system, meaning it won’t harm your newly conceived baby (or babies).

Happily, there are few side effects with Clomid, at least as far as hormone treatments go, and if you do experience them (bloating, nausea, headache, hot flashes, breast pain, mood swings, and in rare cases, ovarian cysts), don’t worry—they’re only temporary. Some women also experience vaginal dryness. Though there’s an increased chance that more than one follicle and egg will be stimulated (you’ll have an 8 percent chance of conceiving twins), your doctor will keep you on the lowest dose possible to keep those chances down. While you’re taking your first round of Clomid, you’ll have to see your doctor or RE often for ultrasounds and blood tests to make sure the drug’s working the way it’s supposed to.

While Clomid is the most common fertility drug, it’s far from the only one. There are other drugs that your doctor or RE might prescribe instead of or in addition to Clomid, all with about the same side effects. Whatever the drug, its mission is the same: to encourage the maturation of eggs. And ready-to-roll eggs are good news when you’re trying to fill your nest.

If Clomid doesn’t do the trick, your doctor might kick it up a notch to hormone injections, which pack a more powerful fertility punch. Your doctor or fertility specialist will put together a cocktail of hormones that you’ll learn to inject yourself with (see box, next page), or your spouse will learn to inject you with if you’re too squeamish. These injectable hormones work directly on the ovaries to help mature the follicles and eggs and stimulate ovulation—basically triggering the same reproductive chain reaction as Clomid, but with much more bang. You’ll use injectable hormones in conjuction with intrauterine insemination (IUI) or, if that doesn’t work, with in vitro fertilization (IVF).

Some possible side effects to hormone injections—though you may not get any—include breast tenderness, mood swings, headache, abdominal pain, nausea, and, in rare cases, ovarian hyperstimulation (in which too many eggs are stimulated, causing pain and possible problems down the line). In most cases, women on these injectable fertility drugs notice more cervical mucus—and that might aid in your conception quest (if you’ll still be trying for a baby the natural way). While on fertility drugs, you’ll have to see your doctor or RE often for ultrasounds and blood tests to make sure everything’s working the way it should be.

Here’s the lowdown on some of the hormone shots you might be needing, but keep in mind that depending on your situation and the preferences of your doctor, you may be prescribed only one or two of these medications:

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). These injections (brand names include Fertinex, Follistim, Puregon, Gonal-f, and Metrodin) act like your own natural FSH to stimulate the development of egg follicles. You’ll need to inject FSH daily, usually starting on days 2 to 4 of your cycle. Your doctor will use blood tests and ultrasounds to monitor the ovarian response, and if necessary, fine-tune the FSH dosage.

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). These injections (brand names include Fertinex, Follistim, Puregon, Gonal-f, and Metrodin) act like your own natural FSH to stimulate the development of egg follicles. You’ll need to inject FSH daily, usually starting on days 2 to 4 of your cycle. Your doctor will use blood tests and ultrasounds to monitor the ovarian response, and if necessary, fine-tune the FSH dosage.

Human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG). While “menopausal” doesn’t sound promising when you’re trying to make a baby, these hormones can deliver. The injections (brand names include Humegon, Pergonal, and Repronex) contain both FSH and LH—two important hormones necessary to stimulate the development of the follicles and the maturation of the eggs. You’ll take the injection daily beginning at the start of your cycle for about 12 days. Blood tests and regular ultrasounds will allow your doctor to monitor how your ovaries are responding to the hormones and whether or not the dosing needs to be tweaked.

Human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG). While “menopausal” doesn’t sound promising when you’re trying to make a baby, these hormones can deliver. The injections (brand names include Humegon, Pergonal, and Repronex) contain both FSH and LH—two important hormones necessary to stimulate the development of the follicles and the maturation of the eggs. You’ll take the injection daily beginning at the start of your cycle for about 12 days. Blood tests and regular ultrasounds will allow your doctor to monitor how your ovaries are responding to the hormones and whether or not the dosing needs to be tweaked.

Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). This sounds more like it (after all, hCG is the pregnancy hormone). The brand names of this type of hormone injection include Ovidrel, Novarel, Pregnyl, and Profasi, and they are used in conjunction with FSH or hMG injections, or even in conjunction with Clomid. When one or more follicles reach the point of no return (ready to release a mature egg), you’ll inject the hormone hCG. HCG is considered the pregnancy hormone because it shows up in your blood and urine once the embryo implants, but in this case, hCG will help trigger ovulation. Another bonus from the hCG: It improves the quality of the uterine lining, effectively plumping and fluffing it for the arrival of an embryo.

Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). This sounds more like it (after all, hCG is the pregnancy hormone). The brand names of this type of hormone injection include Ovidrel, Novarel, Pregnyl, and Profasi, and they are used in conjunction with FSH or hMG injections, or even in conjunction with Clomid. When one or more follicles reach the point of no return (ready to release a mature egg), you’ll inject the hormone hCG. HCG is considered the pregnancy hormone because it shows up in your blood and urine once the embryo implants, but in this case, hCG will help trigger ovulation. Another bonus from the hCG: It improves the quality of the uterine lining, effectively plumping and fluffing it for the arrival of an embryo.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone, or GnRH agonist. Sometimes FSH or hMG injections can stimulate the release of eggs before they are mature. Enter a GnRH agonist (fortunately you don’t have to spell it, you just have to inject it; brand names include Zoladex and Lupron). GnRH agonist works on the pituitary gland to help prevent immature eggs from being released too soon. It does so by first increasing and then suppressing FSH and LH, preventing the LH surge (which triggers ovulation) and allowing additional time for more quality eggs to develop. It also helps produce a higher number of quality eggs. You’ll probably start injecting Lupron just before FSH and hMG shots are started if you’re doing an IVF cycle.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone, or GnRH agonist. Sometimes FSH or hMG injections can stimulate the release of eggs before they are mature. Enter a GnRH agonist (fortunately you don’t have to spell it, you just have to inject it; brand names include Zoladex and Lupron). GnRH agonist works on the pituitary gland to help prevent immature eggs from being released too soon. It does so by first increasing and then suppressing FSH and LH, preventing the LH surge (which triggers ovulation) and allowing additional time for more quality eggs to develop. It also helps produce a higher number of quality eggs. You’ll probably start injecting Lupron just before FSH and hMG shots are started if you’re doing an IVF cycle.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist. Like GnRH agonists, this hormone injection (its brand names include Antagon, Ganirelix, and Cerotide) is used in IVF cycles before FSH and hMG injections are started to prevent a too-soon LH surge—ensuring that eggs are released when they are mature and not before. GnRH antagonists work much faster than GnRH agonists, making this the drug of choice when premature ovulation needs to be prevented right away.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist. Like GnRH agonists, this hormone injection (its brand names include Antagon, Ganirelix, and Cerotide) is used in IVF cycles before FSH and hMG injections are started to prevent a too-soon LH surge—ensuring that eggs are released when they are mature and not before. GnRH antagonists work much faster than GnRH agonists, making this the drug of choice when premature ovulation needs to be prevented right away.

Progesterone. In some cases, your doctor might tell you to inject progesterone daily, beginning 2 days after egg retrieval (if you’re attempting IVF) and ending when the placenta is producing appropriate amounts of progesterone. Progesterone isn’t always given as an injection. You might be able to use a vaginal gel, suppository, or even a pill.

Progesterone. In some cases, your doctor might tell you to inject progesterone daily, beginning 2 days after egg retrieval (if you’re attempting IVF) and ending when the placenta is producing appropriate amounts of progesterone. Progesterone isn’t always given as an injection. You might be able to use a vaginal gel, suppository, or even a pill.

Keep in mind that it may take several cycles and adjustments in your medication cocktail before you hit your optimal fertility prescription. Since every woman’s fertility needs are different, every woman’s fertility treatment plan will be different. To save yourself some stress and confusion, try not to compare your hormone injections to those of other hopeful moms you know (or hang out with on your TTC message board) who are undergoing treatment.

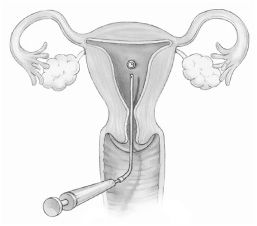

Sometimes, overcoming fertility challenges isn’t just a matter of adjusting your hormones—sometimes either partner (or both) needs a little extra help in making the miracle of conception happen, for a variety of possible reasons. Intrauterine insemination (IUI) is performed when sperm count is low, when sperm have poor motility, when cervical fluid is found to be inhospitable to sperm (as detected in a post-coital test), or when there is just no known infertility cause. IUI can be employed alone—without the use of fertility drugs or injections—or it can be used in conjunction with Clomid if ovulation issues have been identified as well. (IUI isn’t often combined with hormone injections—most often injections go hand in hand with IVF or other assisted reproductive technology). The procedure gives the sperm a better chance of reaching their target by bypassing the initial hurdles they would encounter in the vagina—sort of a running (or swimming) head start.

How does IUI work? Think turkey baster—only a little more sophisticated and a lot more precise. Around the time you’re ovulating (either on your own or with the help of Clomid) and using a sperm sample from your spouse that has been “washed” (the sperm is separated from the semen and the nonmotile sperm are separated from the motile sperm in a centrifuge), your doctor or nurse will insert a thin flexible catheter through your cervix and inject the healthy sperm directly into the uterus close to the fallopian tubes. The same process would occur if you are using donor sperm. In intracervical insemination, the sperm will be placed right at the cervix, and with FAST (fallopian sperm transfer) insemination, the sperm is placed directly in the fallopian tubes. The whole process takes only a few minutes and there isn’t much discomfort (about as much as you’d have during a Pap smear).

Once the insemination is complete, the doctor places a cervical cap into your vagina and on your cervix to make sure the sperm doesn’t drip out. You’ll be able to remove it after a few hours (there’s a string like on a tampon for easy removal). If after trying IUI for 3 to 6 cycles you still haven’t achieved conception success, you’ll likely be advised to move to the next step—IVF.

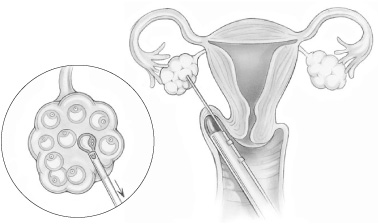

In vitro fertilization (IVF), considered the most effective of the ART techniques, is a good choice when there are blockages in the fallopian tubes, ovulation disorders, or a lot of sperm deficiencies. Here’s how it works: Hormone injections (see page 161) are used over the course of a cycle to help stimulate your ovaries to produce eggs. Around days 12 to 14 of your cycle, the stimulated eggs will be mature and ready for retrieval. But instead of letting them “ovulate” on their own, your doctor will remove them for fertilization in the lab.

The eggs are retrieved transvaginally with a needle that reaches your ovaries and aspirates the egg from the follicle. The egg retrieval takes 20 to 40 minutes on average, and since you might feel some discomfort, your doctor may give you a light anesthetic or pain reliever. While you’re busy with the egg retrieval, your spouse is busy producing a sperm sample. The healthiest eggs (as determined by an embryologist who examines and grades each egg immediately after retrieval) are placed together with “washed” sperm (the sperm is separated from the semen and the nonmotile sperm are separated from the motile sperm in a centrifuge) in a laboratory dish for fertilization. Estimates are that about 80 percent of mature eggs become fertilized during IVF.

Approximately 3 to 5 days after the eggs are successfully fertilized (though it could be shorter or longer than that depending on your doctor’s preference), the embryos (usually more than one, though the number will depend on your choice and that of your doctor, your age, cause of infertility, and other factors) are slowly and carefully transferred into your uterus. Under ultrasound guidance, your doctor will insert a thin flexible catheter through your vagina and cervix into the uterus, and then gently depress the attached syringe containing the embryos, placing them in your uterus with the hope that they will implant and continue to grow just as they would with unassisted conception. You’ll likely rest for a short time (about half an hour) in the recovery room and then be advised to take it easy for a few days post-transfer. Then it’s a 2-week wait from your egg retrieval until the blood test that will confirm whether or not the procedure was successful.

A Look at IVF

Under transvaginal ultrasound guidance, eggs are aspirated from the ovary.

The egg (or eggs) and sperm are placed together in a petri dish for fertilization.

The fertilized egg, or embryo, is placed in the uterus through a thin flexible catheter.

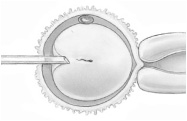

ICSI, pronounced ICK-see, takes IVF one step further, focusing on a solution for male infertility. ICSI is used when the male partner has a very low sperm count, low sperm motility, or poor quality sperm. Instead of merely mixing your eggs and your spouse’s sperm in a petri dish and hoping they get together, seal the deal, and make an embryo, the doctor actually injects a single sperm directly into an egg to assist with fertilization—basically eliminating all of the challenges that the little guy would otherwise have had to face (see illustration, this page).

Here’s how it works: Egg retrieval is the same as it is for a regular IVF cycle. Once the eggs are retrieved, they are “washed” to loosen their protective outer coating. Then the sperm is slowed down with a chemical solution so it’s easier for the technician to “catch” one. Then its tail is immobilized so it can safely puncture the egg’s membrane and be injected deep inside the egg. Once the sperm is injected into the egg, fertilization (hopefully) occurs. As with IVF, if fertilization occurs, the embryo (or embryos) is transfered into the uterus—and less than 2 weeks later, you discover whether mission conception has been accomplished. For couples who undergo ICSI because of male factor infertility, when the woman is under 35 years old, the procedure is successful about 43 percent of the time. Women ages 35 to 37 can expect an almost 37 percent success rate; women 40 and over will have about a 6 to 15 percent chance of conceiving.

A Look at ICSI

A single sperm is injected into

an egg to help jump-start

the fertilization process.

Though assisted hatching sounds like something you’d find going on in a chicken coop, it’s actually a highly specialized ART technique designed to make the implantation process less challenging for a fledgling lab-grown embryo. For an embryo to implant inside the uterus, it must “hatch” out of its protective shell (called the zona pellucide). When you conceive naturally, the trip the embryo takes down the fallopian tube enables the shell to thin, making it easier for the embryo to implant successfully in the endometrium. Embryos grown in a lab, however, don’t have the benefit of that trip down fallopian lane, so some—though certainly not all—embryos created in vitro have a thicker than normal shell and may need an extra push to break out of it. In some women, this extra-thick shell may be the reason previous IVF attempts have failed. Enter assisted hatching—a procedure in which a laser is used to make a microscopic hole in the zona pellucide right before the embryo is transferred to the uterus. This tiny opening enables the cells of the embryo to escape the shell and attach more easily to the uterine wall. What will reproductive science come up with next?

There’s no greater gift than a baby—and gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT) is a procedure that can help deliver that gift to some hopeful couples. GIFT is a more expensive and more invasive ART treatment than IVF, which is why it’s used much less frequently, but it allows fertilization to occur naturally inside your fallopian tube instead of in a petri dish. Eggs are stimulated and retrieved and sperm is collected as with IVF, but instead of having them meet up in the lab for their fertilization rendezvous, the egg (or eggs) and sperm are combined right after retrieval and then placed soon after laparoscopically (through a small incision in your abdomen) into your fallopian tube. The hope is that sperm and egg will fertilize (usually within hours) and turn into an embryo, which will then make its way down to your uterus for implantation.

Because fertilization (hopefully) happens inside your body instead of inside a lab, the success rate with GIFT is relatively high. Experts speculate that the journey through the fallopian tube nourishes the new embryo, giving it a better chance of being healthy and able to implant in the uterus. Another reason for the increased success rate could be because the embryo arrives in the uterus at the “right” time for implantation (as opposed to IVF, in which the embryo arrives in the uterus when your doctor places it there—and that might not be exactly the time frame nature had in mind). Recovery from a GIFT procedure is the same as IVF done through the laparoscope (a few hours of rest and then taking it easy for a few days).

With zygote intrafallopian transfer (ZIFT), the method is similar to GIFT but the eggs are fertilized in the laboratory before being placed (often within hours after fertilization) laparoscopically into your fallopian tube. Why would someone have a ZIFT procedure instead of a GIFT procedure? The advantage to ZIFT is that it’s clear fertilization has taken place. With GIFT, the hope that fertilization occurs is there, but there’s no way to know right away if egg and sperm are actually getting together to make a zygote (an early embryo). In effect, ZIFT gives a pregnancy a running start. ZIFT, like GIFT, is used very infrequently.

Time was, a woman who wanted to experience pregnancy and childbirth had no choice but to use her own eggs, conceiving either naturally or with the help of ART. Which meant that women without viable eggs (because of age or due to ovarian failure or a genetic disorder, for example) were out of luck in the fertility department. The same went for women who were known carriers of serious diseases that they didn’t want to pass on to their offspring. But that all changed with egg donation, technology that gives hope to women who so desperately want a baby of their own. With this ART procedure, an egg (or eggs) from a donor (either fresh or frozen, though fresh are used much more often and with greater success) are mixed with sperm provided by the hopeful father, to produce an embryo. The embryo (or embryos if more than one is being implanted at a time) is then placed in the uterus of the hopeful mom, where it will (hopefully) grow into a healthy pregnancy. Today more than 9,000 babies resulting from donor eggs are born each year with nearly 50 percent of fresh egg donations and 30 percent of frozen egg donations resulting in a live birth.

The first step if you’re considering egg donation is to find an egg donor. A close friend or relative may want to be your egg donor (and if she’s a relative such as a sister, your baby will contain genes resembling yours). Or you might decide to choose an egg from a donor you don’t know through your fertility doctor or through agencies that match donors with recipients (potential donors are screened for genetic disorders, psychological conditions, STDs, and general health, but you will also be able to screen for other genetic factors that matter to you, such as height, hair color, special talents, and so on). You’ll also likely need to involve a lawyer, since there are certain legal issues surrounding egg donation, as well as to factor in the costs involved (those for the donor’s medical care, fees for the donor’s and agency’s services, and legal fees).

Once you’ve chosen an egg donor, it’s time to get ready for a pregnancy—one that involves, at least at this point, three people. Both you and your donor will have to undergo hormonal treatments to coordinate your cycles (though if the eggs or embryos will be frozen for future use, synchronizing your cycles isn’t necessary) and to prepare each of you for your individual job responsibility. Your donor will take fertility drugs (similar to the cocktail of drugs anyone undergoing IVF would use) to stimulate her ovaries to produce multiple eggs—and you’ll use fertility drugs to build up your uterine lining so it’ll be ready for implantation. When your donor’s eggs are mature, they will be retrieved, mixed with your spouse’s sperm in a Petri dish, and the ensuing embryos will be transferred to your uterus within 2 to 3 days (assuming you coordinated your cycles) just like in a regular IVF cycle. If the embryos are to be frozen, transferring to your uterus can be done at any time.

Thanks to advances in sperm-enhancing fertility treatments, the need for donor sperm has decreased somewhat. Still, in many situations sperm donation might be considered. Couples in which the male partner has an extremely low sperm count, no sperm, sperm of low quality, or sperm that carry a genetic defect might turn to sperm donation. Lesbian couples or single women can also turn to donor sperm to achieve a pregnancy.

Finding a sperm donor is easier—and less expensive—than an egg donor for one simple reason: The sperm donation process is so much simpler than the egg donation process. Sperm banks screen donors for diseases (including STDs), get a family and medical history, and test for some genetic disorders. They’ll also allow you, if you wish, to peruse profiles of prospective donors (some offer more detailed profiles than others, though usually such services come at a higher cost). These profiles can provide a snapshot (sometimes literally) of the man behind the sperm—everything from height, hair color, IQ, education, hobbies, and so on—so you can do some screening of your own. If you’d rather, you can also choose the donor randomly, without knowing any details about him. One pertinent bit of information you’d probably want to know: how many times a particular man has become a biological father through donation. You can also choose to use sperm from someone you know (though he’ll have to undergo a screening process as well).

Once a sperm donor is chosen, his frozen sperm will be thawed and you’ll either be inseminated with the sperm via IUI or you’ll undergo an IVF cycle to mix your egg with the donor sperm in the lab.

When a woman wants a baby but can’t carry a pregnancy, she and her partner can turn to a surrogate—another woman who can carry the pregnancy for them. There are two types of surrogacy: Gestational surrogacy is when a woman (called the gestational carrier) carries a baby that is not biologically related to her. This might be an option if you have viable eggs, want a biological child, but can’t carry a baby yourself (because you can’t sustain a pregnancy, don’t have a uterus, have a medical condition that makes pregnancy dangerous or impossible, or for another reason). The embryo formed in vitro with your eggs (which are retrieved as they would be for IVF) and your partner’s sperm is then transferred to the gestational carrier’s uterus, where it grows until the baby is ready to be born. Since the baby is yours, there’s no need for adoption once the baby is born.

In traditional surrogacy, the surrogate’s own egg is inseminated with the sperm from the male partner of an infertile couple and the infertile couple may legally adopt the child after birth (laws can vary from state to state, so be sure you consult with a reproductive attorney). Traditional surrogacy might be an option if you don’t have any viable eggs, can’t carry a pregnancy, and still want a baby that’s biologically related to your partner. It can also be used to make a gay couple parents.

A surrogate can be a close friend or family member—though some surrogates are “strangers” recruited by the couple to carry the pregnancy. Keep in mind that some states prohibit surrogacy.