THE SERIOUS BUSINESS OF JEWISH FOOD AND FUN IN THE 1950S

RACHEL GROSS

IN THE 1950s the Jewish publishing house KTAV embarked on a quest to capture the hearts, minds, and stomachs of American Jewish children. Educators feared that unless they made Jewish children’s education more entertaining, the young baby boomers would rapidly lose interest in their cultural and religious heritage. Against the force of what one Jewish journalist called children’s “ordinary (and, as a matter of fact, entirely absorbing) American life,” traditional Jewish forms of acculturation at home would not suffice and, worse still, were no longer reliable, while classroom instruction seemed of no avail.1 A critique of the conventions of formal Jewish education had been part of the American Jewish communal conversation for some time; as early as 1920 one veteran of Hebrew school declared that he held Jewish afterschool religious instruction responsible “for the larger part of dislike for all things Jewish,” and it was generally acknowledged that there were far more interesting ways for Jewish children to spend their time in the increasingly commoditized world of American children’s entertainment.2 Jewish children in America had, it seemed, fully assimilated to the mainstream culture of American youth and lacked knowledge of and interest in Jewish culture and religious practices. American Jews needed a new, more fun way to impart religious knowledge and culture to the next generation.

Highlighting postwar Jews’ anxieties about the future of their religious practices and culture, KTAV’s 1956 publication of the Junior Jewish Cook Book by Aunt Fanny taught children to enact social identities that vacillated uneasily between the markedly Jewish, the modern American, and a self-consciously diverting blend of the two. While cookbooks designed for Jewish American children abound today, the Junior Jewish Cook Book is the earliest example of this genre.3 Published by KTAV, one of the first distributors of American Jewish children’s educational material, and pseudonymously authored by Sol Scharfstein, its enterprising president, the slim, sixty-four-page volume aimed to synthesize children’s bifurcated American and Jewish identities through the palpable and playful medium of food.

At a glance the style of the cookbook’s text and illustrations mimics popular mainstream counterparts such as Betty Crocker’s Cook Book for Boys and Girls (1957) and Mary Alden’s Cookbook for Children (1956). Its recipes range from traditional Jewish dishes with eastern European origins such as potato kugel (a baked pudding or casserole) to 1950s staples like hamburgers and creative concoctions designed to entertain young cooks, such as Noah’s Ark cookies. The book’s wide spectrum of recipes, from fried fish to baked bananas, was intended to strengthen its young readers’ Jewish home lives. American Jews had moved out of ethnic urban neighborhoods into suburbs, where they were eager to assimilate into mainstream America. Definitely Jewish but not “too Jewish” in appearance so as not to repel Jewish suburbanites eager to shed idiosyncratic religious and ethnic identifiers, the Junior Jewish Cook Book encouraged its young readers to participate in normative American culinary practices by purchasing canned and packaged goods, using modern kitchen implements, and arranging food in fanciful forms according to current mainstream tastes, but to do so in service of Jewish practices. Using a children’s cookbook format, a popular and distinctly American form of entertainment, KTAV linked Jewish practices to American foodways and recreation. Through the presentation of a series of seemingly light-hearted holiday-themed recipes, the cookbook encouraged children to take Jewish culture into their own hands, fostering excitement about their heritage through play.

The need for an altered approach to children’s instruction arose as American Jews reorganized their communities in the postwar suburbs. In contrast to urban Jewish neighborhoods of an earlier generation in which Jewish identity developed organically, Jewish life in this new environment required self-conscious choices and activities, leading to a perceived distinction between the practice of “Judaism” the religion and a sense of participation in “Jewishness,” a culture.4 Religious precepts and practices could be taught, but how did one teach a social identity? In a 1949 review of Jewish children’s books in Commentary, Isa Kapp addressed the challenge of not only teaching children religious practices but also passing on a culture:

A tone (and it seems to me that the Jewish tradition consists in large part of tone . . .) can only be absorbed haphazardly and to a large extent unconsciously, in the gradual, thoughtless way that a child comes to know that he is an American, that his home is in the city, that he is more interested in science than in music. There is a difference between overhearing a family joke and memorizing a sugared jingle, the difference between spontaneity and artifice.5

But Jewish leaders feared that many children would not come by this vaguely identified “tone” of Jewish culture naturally, through parental guidance. To acculturate children in the most natural and attractive way possible, KTAV and other Jewish publishers launched onto the market a blitz of “alphabet blocks, spelling games, coloring books, flip charts, film strips, fun books, cassettes, workbooks, and notebooks along with graduated texts” in order to interest children in Jewish living and education.6 Through their appealing, up-to-date products for children, publishers rebranded Judaism as fun and playful, giving games a not-so-hidden objective. Jewishness would reach children through the guise of recreation.

Using a cookbook to acculturate Jewish children made sense for American Jews: as historian Hasia Diner identifies, Judaism’s traditional ritual requirements “put food in the foreground,” so teaching children to link Jewish identity and eating followed cultural norms.7 At the same time, Jews, along with other Americans, were adapting to the rapidly changing food mores of postwar America. Notions of domesticity and child’s play were changing too. Burdened by Cold War concerns about atomic weapons, still reeling from World War II, and shaped by the legacy of the Depression, Americans enthusiastically and assiduously created a family-centered culture that historian Elaine Tyler May identifies as a “psychological fortress” against perceived social and political threats. Pediatrician Benjamin’s Spock’s description of play as “serious business” in his 1946 bestseller, Baby and Child Care, epitomized this trend.8 As Dr. Spock and others urged the professionalization of child rearing, KTAV marketed professional aids for raising Jewish children, working to normalize American Judaism within mainstream culture by equating Jewish and American identities through food and fun.

“AN ATMOSPHERE OF ANXIOUS CONCERN”

The Junior Jewish Cook Book spoke to a generation of Jewish children whose experience of Judaism differed dramatically from that of their parents, themselves largely the children of European immigrants who arrived at the turn of the twentieth century. In his influential work Protestant–Catholic–Jew, the eminent Jewish sociologist Will Herberg identified the plight of Jewish baby boomers who “became American in the sense that had been, by and large, impossible for the immigrants and their children.” Nonetheless, issues of belonging and identification remained unresolved. “They were Americans,” worried Herberg, “but what kind of Americans?”9

Herberg might have done well to question what kind of Jews they were as well. In the years following World War II, middle-class migration to the suburbs had an indelible impact on the communal structures of American Judaism. Though Jews suburbanized more rapidly and in larger numbers than other Americans and tended to live in neighborhoods surrounded by other Jews, they viewed their move from the ethnic neighborhoods of the city as a demonstration of their participation in mainstream American culture. In its new suburban context, the Jewish community had more organizations, especially denominationally affiliated synagogues and Jewish community centers, but despite the numbers, many Jews saw their suburban communities as “diluted and pallid” and “less Jewish” than the urban Jewish life of an earlier era.10

Having largely rejected the Orthodoxy of their elders, the second generation now relied heavily on Jewish organizations to educate their children while leading home lives undifferentiated from those of their non-Jewish suburban counterparts. As a result, synagogue services, religious education, and other Jewish activities seemed divorced from their children’s everyday, secular American lives. In the 1954 pamphlet “Perplexities of Suburban Jewish Education,” Dr. L. H. Grunebaum wrote:

Children . . . suffer from a kind of mild schizophrenia. Here are the rabbi, director, cantor and teachers; there are the parents. . . . Here is supernaturalism, prayer, the Ten Commandments, Jewish customs and ceremonies. There is science, atomic facts, sex and Mickey Spillane, American ways and values. . . . So it comes about that the attempt to make children more secure as members of the Jewish community has in many cases the opposite result.11

Without the dynamic, continual ethnic reinforcement of Jewish neighborhoods in the city, the maintenance of the Jewish identity of the next generation seemed imperiled. To counter this, Jewish authors and educators sought fresh ways to interest American Jewish youth in their heritage, attempting to fill the perceived Jewish gap at home. Recognizing the limited value of formal education, too easily dismissed as stiflingly boring, they turned their attention to playtime.12 New Jewish storybooks, biographies, and activity books were intended to foster a culture of Jewish childhood that might not arise organically.

In this context, the cheerful, seemingly innocuous genre of Jewish children’s books bore heavy communal expectations. The editors of Commentary summed up the prevailing attitude of American Jews in an introduction to Kapp’s 1949 review of Jewish children’s books: “An atmosphere of anxious concern surrounds the production of children’s books for Jewish children. Can they be counted on to make our youngsters conscious, self-respecting Jews? Or—others ask—do they stress Jewish uniqueness (or Israeli prowess) so much as to separate and estrange Jewish children from the common American life?”13

By the 1950s KTAV Publishing House had expanded from a small Jewish bookstore to a major business, just beginning to have a significant influence on Jewish education; today it is a major Jewish publishing house. The brothers Sol and Bernie Scharfstein built up the business, which they named KTAV, Hebrew for “writing.” In 1951 Sol Scharfstein wrote KTAV’s first book, a popular “Dick and Jane” style Hebrew reader called Chaveri, “my friend.”14 He continued to write and publish texts designed for Jewish classrooms and homes over the next six decades. “Anything that improves Jewish education, even a little toy, has some value,” Scharfstein later explained.15

Expanding their efforts to interest children in Judaism and Jewish culture, KTAV and other Jewish publishers began to publish books of Jewish-themed activities, in addition to storybooks. Children needed to take a more active role in their acculturation, to “play the games, paste the pictures, solve the riddles and enjoy reading the stories.”16 Interactive books made being Jewish a fun activity, not a lesson or a story to be passively absorbed.17 The Junior Jewish Cook Book took this educational technique a step further, as an activity book with palatable results, quite literally providing a taste of Judaism.

“COOKLESS COOKERY” AND CREATIVITY

Even as it entered the changing world of the Jewish marketplace, the Junior Jewish Cook Book appeared amidst the burgeoning cookbook industry of the 1950s, a decade that would become infamous for the ubiquity of its packaged foods. In linking Judaism with cooking, KTAV did not tie the former to a stable social entity. The kitchen prompted at least as much communal anxiety among Americans at large as Jewish home life did among Jews. As marriage and birthrates soared after World War II among Jews and non-Jews alike, and couples raised families in newly developed suburbs, postwar America saw an unprecedented expansion of cookbook production. Although cooking served as the quintessential expression of middle-class femininity, 1950s cookbook authors assumed that young wives of the postwar marriage boom had little or no experience in the kitchen.18 In this “era of the expert,” suburban women required formal instruction to fulfill their social function and nourish their growing families.19

Not only did American home cooks appear less experienced and more open to professional advisement than did their mothers, but the contents of their kitchens had also undergone a dramatic transformation. Following World War II, myriads of astonishing timesaving household appliances became affordable for the middle class for the first time. Refrigerators and freezers brought new food products into the home, and electric stoves and ovens, blenders, dishwashers, and other appliances reshaped housewives’ work. Encouraged by the development of rations for the army and the home front during the war, enthusiastic scientists and manufacturers put an array of canned, frozen, and packaged foods on the market.20

Embracing these symbols of idealized suburban ease, cookbook authors provided bewildered housewives with instructions on how to use the new culinary devices properly and how to serve prepared foods. Aided by new marketing techniques, the food industry promoted a new way to think about cooking, emphasizing creativity over labor. Manufacturers and cookbook authors (sometimes one and the same) taught modern housewives how to save time and energy by using prepared foods and modern culinary appliances, while maintaining a personal involvement and ownership over their creations by “doctoring up” or “glamorizing” the food they served. The modern housewife “may spend less time in the kitchen and she may buy canned food,” wrote Ernest Dichter, the psychologist who pioneered the new fields of advertising and consumer behavior studies, “but she makes up for it by greater creativeness.”21 What popular cookbook author Poppy Cannon termed the “social art” of “cookless cookery” combined the moral responsibility of the housewife with the modernity and ease of manufactured goods.22 The 1950s food culture made creative rearrangement the highest accolade in a world of manufactured uniformity, strikingly exemplified by Beth McLean’s New Pineapple Look in the Modern Homemaker’s Cookbook, a “good-tasting fake” consisting of liver sausage molded to look like a pineapple, covered by sliced olives serving as pineapple skin and topped by a real green pineapple top.23 Whatever their final shape, the inclusion of canned and packaged ingredients in postwar recipes made manifest the modern American refinement and ingenuity of both cookbook author and home cook.

Strangely enough, even as cookbooks emphasized manufactured goods, they became more inclusive of recipes from other cultures—or at least American adaptations of them. In the late nineteenth century, proponents of scientific cooking and cooking school experts had urged immigrant families to give up the dishes of their homelands for a more uniformly “American” diet consisting of bland New England fare.24 Accordingly, most American Jewish cookbooks published before World War II neither included distinctively Jewish dishes nor followed kashrut (the Jewish dietary laws), attempting to moderate what were seen as outlandish ethnic identifiers. But by the 1950s American culinary trends broadened to accept adaptations of immigrants’ foodways. The Complete American Cookbook (1957), for example, included recipes for chow mein, Javanese rice, tamale pie, egg foo young, and Italian sausage in cabbage leaves. Denominational cookbooks, like Catholic Florence Berger’s Cooking for Christ: The Liturgical Year in the Kitchen (1949), now explicitly linked ethnic foodways with religious practices. “Most American families threw their spiritual and social traditions into the sea when they left Europe,” Berger lamented. “They no longer wished to appear Dutch or French or Swedish—so they left you and me without a background”—a situation she fought by sharing recipes for German “Easter sweet bread,” Italian “St Joseph sfinge (cream puffs),” and Greek spice cake.25 Amid a torrent of increasingly specialized recipe books, Jewish cookbooks came into their own, reconfiguring the traditional fare of Eastern European Jews as American food and an increasingly diverse vision of “American” food as Jewish: The Complete American-Jewish Cookbook (1952) adapted “an amazing collection of American, Continental, and even international recipes” to accommodate Jewish dietary laws, including, as its advance publicity heralded, egg foo young and boo loo gai.26

“PITY THE POOR YOUNG PALATES”

Just as the cookbook industry was expanding, children’s entertainment underwent rapid growth, accommodating the unprecedented size of the postwar baby boom generation. Cookbooks, like other modern, adult instruments, were adapted as novelties for children’s play, and a surge of children’s cookbooks entered the market in the postwar years.27 With playful and simplified culinary trends in vogue, it was no great stretch for food manufacturers and cookbook authors to turn women’s work into child’s play in juvenile cookbooks. Like their counterparts for adults, children’s cookbooks in this period tended to emphasize combining or reheating canned, processed, or frozen ingredients, often promoting the products of manufacturers such as General Mills and Quaker Oats. In these recipes, preparation of premade food served as an easy method for girls to learn to imitate their mothers in the kitchen and introduced them to the modern market at an early age.

Aimed primarily at girls, juvenile cookbooks echoed the culinary habits and gendered social roles of cookbooks aimed at adults. While cookbook authors encouraged the boomers’ mothers to take ownership of new packaged goods by “doctoring up” their dishes, arranging them in trendy, creative shapes, children’s cookbooks encouraged children to engage in “food fun,” a child-sized version of the same fad. Cookbook authors seemed convinced that children loved to make and eat food shaped like animals or disguised as other food.28 Symptomatic of this trend, Good Housekeeping’s June 1950 issue commended an editor on her practice of shaping her nieces’ and nephews’ dinners into storybook images. The magazine carefully documented her transformation of mashed potatoes, cottage cheese, or scrambled eggs into an edible Humpty Dumpty with pea eyes and nose and carrot mouth, sitting on a chopped-spinach wall.29 Feeding children deserved careful consideration and advice from experts, from Good Housekeeping to Dr. Spock, and a lighthearted playfulness belied the serious issues at stake.

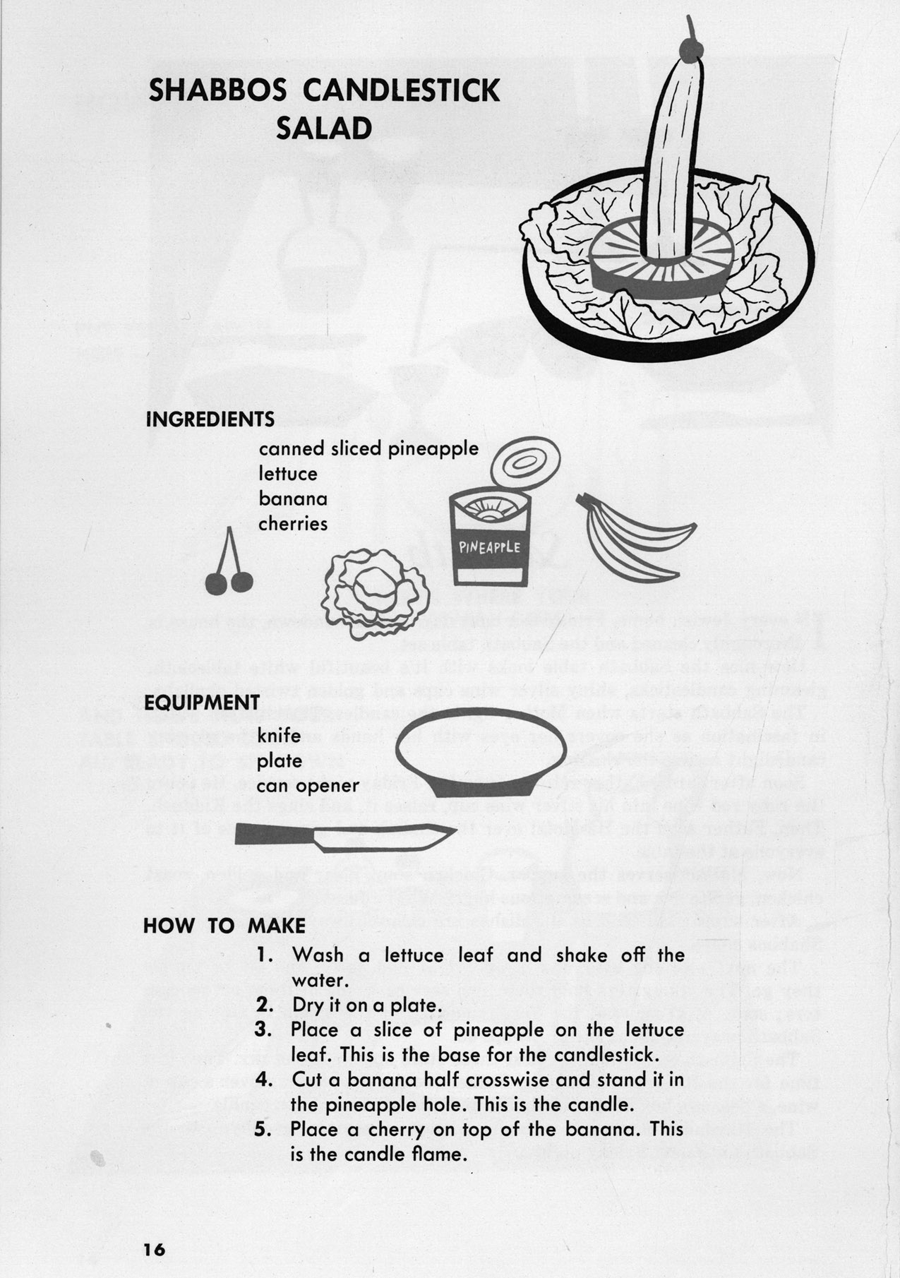

Such whimsical food arrangements had trickled down from the creative preoccupation of modern suburban housewives to their children’s playtime. In 1954 Saturday Review bemoaned the reappearance of the once-fashionable candlestick salad in a children’s cookbook: “it was rather disheartening to see that bridge-club pest of yesteryear turning up again—a fantasy consisting of lettuce leaf, one slice of canned pineapple with a half banana standing upright at its center, the whole thing dripping with mayonnaise. But perhaps—pity the poor young palates!—it has found its niche, a birthday party attended by befrilled small girls.”30 Despite reviewers’ exhortations, food arrangement moved from the business of homemakers to child’s play, instructing children in modern attitudes toward food, with all their fanciful trends and serious implications.

SHABBAT CANDLESTICK SALAD

In the Junior Jewish Cook Book, KTAV Publishing House applied this modern fad to Jewish communal purposes. They were not the first to do so: a 1953 Commentary review chided the authors of The American-Jewish Cookbook for including “a horror titled ‘Menorah Salad’—a representation of a candle-stick done in fruit and vegetables.”31 Similarly, with a simple name change, the classic candlestick salad became the Junior Jewish Cook Book’s “Shabbat Candlestick Salad.” Children could transform “just plain food” into “a social art” while celebrating Shabbat, the Jewish Sabbath. By tying familiar foodways to a Jewish practice, the Junior Jewish Cook Book employed American culture in the service of Judaism, merging children’s American and Jewish identities. At the same time, it made Jewish education fun: children could play with their food while learning about the ritual of lighting candles on Friday nights, the eve of Shabbat. The activity demonstrated that American and Jewish values were in accord and even enhanced each other, as did biblically inspired recipes such as Noah’s Ark Cookies and Queen Esther Salad.

Playfulness also served to sugarcoat the cookbook’s pedagogy. A recipe for draydel salad called for children to place raisins on top of the pear halves in the shape of the Hebrew letters on the dreidel, bounded by banana wedges arranged in the shape of the Chanukah top. Jewish children could learn Hebrew letters and Jewish customs through tactile and edible means. If they did not replace the oft-bemoaned Jewish Sunday school, such practices could serve as a delightful supplement. Preparing typical 1950s fare in celebration of a Jewish holiday, children played with their food just like their non-Jewish neighbors, guided by sources like Good Housekeeping, while forging a stronger connection to Jewish culture.

Despite, or because of, its Jewish theme, the book’s appearance and layout carefully echoed those of non-Jewish juvenile cookbooks of the 1950s, with straightforward, easy-to-follow recipes accompanied by simple, attractive illustrations of the ingredients, the necessary culinary equipment, and the finished dish. It diverged from mainstream children’s cookbooks, however, in its organization, instead following Jewish cookbook convention by dividing recipes according to their association with Jewish holidays rather than by the type of food or method of preparation. Its appearance and layout managed a comfortable and practical compromise between the two genres, actually performing the synthesis of Jewish and juvenile American identities that its intended audience should achieve.

“TO BECOME A JEW BY FREE ASSOCIATION”

Before the market grew larger and more specialized, midcentury Jewish children’s books appealed to a wide audience, across denominational lines. Like other Jewish children’s activity books, the Junior Jewish Cook Book promoted Jewish-themed play without presuming any level of Jewish observance or foreknowledge by the reader, following KTAV’s goal of promoting “Jewish education and generational continuity” across the board.32 The book was marketed to emerging gift shops of suburban Conservative and Reform synagogues, just beginning to appear as a resource for instructing parents and children in creating a Jewish home life.33 Attempting to avoid alienating Jews who did not follow kashrut, the Junior Jewish Cook Book downplayed the role of ritual dietary laws, in contrast to Jewish cookbooks for adults, frequently marketed with the subtitle “in accordance with the Jewish dietary laws.” Although the Junior Jewish Cook Book also contained a note assuring readers who cared that its recipes followed kashrut, it appeared in small font on the third page, not on the book’s cover. Jewish children might easily follow KTAV’s recipes without keeping kosher, even without an awareness of kashrut, since the book provided no explanation of that practice. Recipes were not labeled milchig (dairy) or fleishig (meat) to facilitate the user’s practice of kashrut, as is common in later Jewish children’s cookbooks. By minimizing mention of kashrut, the cookbook refrained from imposing ideology or ritual practices upon its young readers, leaving such formal instruction to the discretion of their parents. Instead, it encouraged Jewish unity through the tangible, sensory experience of making food and eating in celebration of Jewish holidays.

FIGURE 5.1 Junior Jewish Cook Book adapted a cocktail party dish, candlestick salad, to teach children about the Jewish Sabbath. Author’s collection; used with permission of KTAV Publishers.

FIGURE 5.2 Draydel Salad made learning about Chanukah traditions and Hebrew letters a tactile and edible experience. Junior Jewish Cook Book. Author’s collection; used with permission of KTAV Publishers.

Extraneous commentary in Junior Jewish Cook Book underscores the communal anxiety underlying the cookbook’s educational aims. A small note, for example, introduces the recipe for the once popular Jewish dish of fried fish: “Fish has always played an important part in all holiday and Sabbath meals. Serve cold fried fish at your Saturday and holiday afternoon meals. Serve fish with potato salad and pickles.”34 Such explanations were intended to subtly acculturate children to Jewish domestic practices; rather than detailing the correct ritual practice of Shabbat, the cookbook encouraged eating potato salad and pickles—familiar, Americanized versions of Eastern European Jewish foodways. More than providing religious instruction, KTAV aimed to acculturate children to cultural signifiers that it feared might disappear in the American melting pot.

KTAV’s effort to speak to a readership with varying degrees of familiarity with Jewish culture provides a glimpse into American Jews’ practices in the 1950s. The cookbook includes a summary of Jewish holiday customs, placing a holiday story and a description of its observances before each group of recipes. After describing Friday night home rituals, the Shabbat section narrates, “The next morning everyone is up bright and early, and off to temple they go. The youngsters hold their own service. Some of them act as cantors; some of them read the Torah; and all of them join in singing the Sabbath prayers just as the grownups do.”35 Here children act independently but mimic the ritual and liturgical activities of the adult community. Aiding children in leading services and cooking for holidays on their own, KTAV hoped that children would come to explore Judaism independently, learning by doing and gaining an attachment to Jewish practices through their performances. In her review of Jewish children’s books, Kapp explained that for children, “the real fun is to be left to one’s own devices, to stare unnoticed at busy adults, to discover unexpected gestures and voice intonations, to become a Jew by free association.”36 KTAV did not trust that Jewish children would acquire Jewish knowledge and identity if left entirely to their own devices, but it did its best to foster their Jewish sensibilities, providing the resources for Jewish child-only activities.

“EVERYONE’S FAVORITE”

Associating Jewishness with the fashionable ease of “cookless cookery,” the ingredients of the Junior Jewish Cook Book’s recipes often feature cans and boxes. Queen Esther Salad, an edible arrangement of a simple face adorned with a crown in celebration of the holiday of Purim, consists exclusively of packaged food, emphasized by illustrations of a can of almonds, a bag of raisins, a can of pineapple, and a container of cottage cheese; one placed raisins on a round ball of cottage cheese to form the face, while almonds served as jewels in a pineapple crown. Pancakes, associated with Chanukah, are made from a mix, while the more challenging fried fish is made with a staple of the modern American Jewish kitchen, packaged matzo meal.37 To the 1950s reader, the inclusion and creative arrangement of these ingredients proclaimed that Jewish cooking could be modernized. American Jews had enthusiastically embraced the growing market of packaged foods; kosher packaged food items, certified as ritually permissible, demonstrated the synchronicity of modernity and religious practice.38 As kosher items appeared with increasing frequency on the shelves of mainstream grocery stores, one no longer needed to live in an ethnic enclave to participate in Jewish culinary culture. Jewishness could be bought prepackaged and rearranged to suit one’s tastes.

KTAV boldly appropriated not only canned food but also quintessentially American dishes by associating them with specific holidays. Eating popular American food became a key element of holiday fun. A note accompanying a recipe for patties of ground meat prepared with store-bought breadcrumbs and canned tomatoes declared, “Meatburgers are everyone’s favorite. Try these as a main dish for one of your Sukkos meals,” seemingly arbitrarily connecting burgers to the practice of eating outside in a sukkah, a small, temporary booth for the fall harvest holiday.39 While another note in the book described kugel as “everyone’s favorite,” implicitly referring exclusively to American Jews, here “everyone” refers to a general American public.40 This declaration is prescriptive; as a true American, the Jewish reader should enjoy this quintessentially American dish. With this phrase, the Junior Jewish Cook Book normalizes seemingly exotic Jewish practices, making them fun for a juvenile audience with American sensibilities. In neatly planned suburbs, Jews’ practice of eating in a sukkah would stick out as exceedingly strange. But with the inclusion of hamburgers, a family’s celebration of the holiday might be mistaken for a barbecue, a recognizable suburban practice. Through the cookbook’s manipulation of food culture, the holiday becomes a characteristically American party associated with the supposed ease of suburban living.

PLAYING GROWN-UP

Scharfstein’s inclusion of the character Aunt Fanny as the author of his cookbook also spoke to mainstream culinary trends. As food companies taught children and adults new ways to cook and eat, many created fictional female characters to serve as the public face of the company and provide advice to women on modern home economics. The most successful of these characters, General Mills’s Betty Crocker, was often mistaken for a real home economist, with her signed responses to women’s letters and appearances on radio and television.41 The character guided baby boomers as well as their mothers in Betty Crocker’s Cookbook for Boys and Girls.42 She and her brand-name compatriots taught postwar children not only how to cook, but how to shop and to which brands they should be loyal. Even more so, they coached young cooks in the complexities of gender dynamics in the kitchen.

The link between children’s play and women’s work in the Junior Jewish Cook Book was not incidental. Since at least the 1920s, girls’ toys have centered on the home, epitomized by dollhouses and kitchen sets.43 Postwar children’s cookbooks took gendered play a step further, turning the kitchen into the playroom and foreshadowing the popular 1960s Suzy Homemaker toys, a line of real, working household appliances for girls. Such works encouraged girls to play make-believe within conservative, gender-specific roles, even as women were challenging traditional gender divisions at home and in the workplace.

While mainstream juvenile cookbooks made cursory and uneven overtures to boys as well as girls, the Junior Jewish Cook Book directed itself to both genders, featuring both a girl and a boy wearing toques on its cover. Nonetheless, it maintained contemporary gender norms in the fictional culinary authority of Aunt Fanny, whom Scharfstein named after his mother, and by acknowledging readers’ mothers’ jurisdiction over the kitchen. Still, the Jewish cookbook’s underemphasis on readers’ gender is exceptional among juvenile cookbooks. Lacking reference to the users’ gender through language or illustration beyond the cover, the book primarily aims to acculturate children of both sexes to Jewish practices rather than to delineate gender roles.

“RECIPES FOR LIVING”

KTAV’s method of acculturating children to Jewish norms and folkways rather than offering straightforward instruction on theology or religious observance can best be highlighted by comparison with a Christian analogue. The Evangelical Moody Bible Institute published Frances Youngren’s Let’s Have Fun Cooking: The Children’s Cook Book in 1953, just three years before the publication of the Junior Jewish Cook Book. Let’s Have Fun Cooking contains an assortment of clearly written recipes accompanied by Bible verses, stories, graces, and prayers.44 The two cookbooks correspond visually, drawing from the same set of simple clip-art images of ingredients, culinary equipment, and figures of children and chefs. Their recipes, too, included a similar range of hot dinner entrées to simple snack foods, with an emphasis on snack foods prepared from packaged goods. Jews and Evangelicals, both outside the mainstream of American Protestantism and each with a stake in proving their truly American character, worked to tie religious identities to mainstream American culture in the form of modern children’s cookbooks.

But unlike the Jewish book, which organizes its recipes by holiday and links children’s Jewish identity with foodways, Let’s Have Fun Cooking provides no connection between the food and its religious context beyond the use of weak metaphors. Its table of contents divides the material into “recipes” and “recipes for living,” and an introductory letter explains that the book contains instruction about “two kinds of food . . . food for you to cook and Bread for you to feed on. For just as your bodies need good food to grow and develop, so does your soul need to be fed.”45 While the Jewish book includes notes to the reader linking the recipes to religious practices, the Christian cookbook juxtaposes theological material with food without explanation; one set of facing pages places biblical verses about creation opposite a recipe for Frankfurter quails.46 With the exception of communion, Christian food, unlike Jewish food, derived its denominational significance from the religious setting in which it was prepared or eaten, not from components of the dishes themselves.47

While the Jewish children’s cookbook included descriptions of holidays, Let’s Have Fun Cooking interspersed short, explicitly theological stories among the recipes, concluding heartwarming stories by questioning young readers, such as “Have you been cleansed by the precious blood of the Lord Jesus Christ?”48 In contrast, the Jewish cookbook rarely mentions God but uses cooking and eating as a Jewish practice through which children could construct their Jewish identities. In keeping with differences between Christian and Jewish practices, while Christian children were taught the fundamentals of their faith, Jewish children were taught how to participate in the Jewish community by preparing and sharing food in order to celebrate Jewish holidays in a distinctly American style.

PRAYING GENTEELLY

Both the Christian and Jewish children’s cookbooks taught children how to mimic their elders in behavior as well as religious practices, evinced by their inclusion of etiquette rules. As Jews and Evangelicals made a conscious effort to be respectable Americans, adherence to social conventions was not insignificant. But while the Christian book includes an etiquette section as an afterthought on its final page, several pages of “Rules of Etiquette” precede the recipes in the Jewish book. KTAV instructed children to “always wash your hands before starting to eat,” “eat quietly without making any undue noise,” and “don’t be afraid to try a new food” because “all food is good.” This blanket categorization of all food as “good” has a highly ambiguous tone that might be interpreted as a subtle move away from kashrut, which defines food as ritually acceptable or unacceptable for consumption. In the effort to integrate American and Jewish sensibilities, not only what one ate but also how one ate was significant.

The final etiquette rule in the Junior Jewish Cook Book suggests that children say the following grace before meals:

Thank you God,

For bread and meat,

We pray that others too,

May have enough to eat.49

This rhyme makes it clear that KTAV did not have an Orthodox or ritually observant audience in mind. Though the book recommends the Jewish tradition of praying before and after eating, in contrast to the Christian grace said only before a meal, it offers a generic premeal prayer that might have easily appeared in the Christian Let’s Have Fun Cooking. Moreover, the inclusion of this prayer among etiquette rules rather than alongside descriptions of holiday customs reveals a seam in the still-uneasy joining of American and Jewish practices. Reciting this brief prayer—the only mention of God in the cookbook—imitated Christian practices without explicitly contradicting traditional Jewish practices. Ultimately the Junior Jewish Cook Book left the final decisions about Jewish observance in the hands of the young readers’ parents while endorsing American culinary sensibilities. Extremely equivocal, it attempted to appeal to Jewish families across the spectrum of religious observance and Jewish knowledge while avoiding a strong endorsement of practices that would set Jewish diners apart from their non-Jewish neighbors.

Burdened by communal concerns over the identity of young American Jews, the Junior Jewish Cook Book vacillates uneasily between leaving children space to synthesize their bifurcated identities on their own and providing prescriptive instructions on how to enact American and Jewish identities. At times, the book insists on an increasingly rare religious reality. The sweeping inclusiveness of statements such as “In every Jewish home, Friday is a busy day. Before sundown, the house is thoroughly cleaned and the Sabbath table set” gestures toward a normative Jewish home life that KTAV wanted to encourage rather than conveying the actual state of affairs in 1956.50 By publishing the Junior Jewish Cook Book and other hands-on activity books, KTAV aimed to fill a perceived void in Jewish homes, where children might not otherwise naturally acquire a “Jewish tone.” In this endeavor American culture was both threatening and desirable. Jewish communal leaders feared that Jewish children would be seduced by American entertainment, but they also wanted them to identify as fully American.

Participating in the mainstream “domestic revival” of the 1950s, the Junior Jewish Cook Book aimed to create a distinctly Jewish home life using forms and images created by non-Jewish culture. Following the cookbook’s instructions, Jewish children not only read stories, dressed dolls, and pasted pictures in the service of their multiple identities but enacted and reinforced both their Jewish and American identities by playing in the kitchen, chopping vegetables, boiling noodles, mixing cake batter, and, finally, eating the fruits of their labors according to carefully constructed recipes. Unlike the Christian Let’s Have Fun Cooking, the Junior Jewish Cook Book made no attempt to dictate belief and gestured only minimally toward ritual practices. It reached for something less defined and perhaps more difficult to achieve: the development of children’s enthusiastic attachment to Judaism through domestic practices, in concert with their normative American identities and as enjoyable as their mainstream games. Jewish foodways should appear as American as canned pineapple and as fun as playing with dolls, though the book’s didacticism belies the naturalness its publishers wished to convey. The cookbook vehemently insisted that American Jewish children could happily incorporate both cultures into their lives and play, at least in the kitchen, where they could create burgers and kugel and serve hamantaschen and marshmallow pops side by side.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. What kind of American Jewish identity did the Junior Jewish Cook Book teach to children?

2. How did creative food preparation demonstrate home cooks’ modern sensibilities?

3. In what ways did the Junior Jewish Cook Book use mainstream food culture for Jewish communal purposes? How did it subvert them?

4. How was the Junior Jewish Cook Book different from or similar to the Christian Let’s Have Fun Cooking? What does the comparison suggest about American Jewish culture in the 1950s?

5. What kind of cookbook, recipes, and ingredients are indicative of American society today?

NOTES

1. Isa Kapp, “Books for Jewish Children: The Limits of the Didactic Approach,” Commentary 8 (December 1949): 547.

2. Quoted in Jenna Weissman Joselit, New York’s Jewish Jews: The Orthodox Community in the Interwar Years (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 35.

3. Sol Scharfstein, Junior Jewish Cook Book by Aunt Fanny (New York: KTAV, 1956); and Bernard Scharfstein, president of KTAV, telephone conversation with author, November 11, 2010.

4. Riv-Ellen Prell, “Community and the Discourse of Elegy: The Postwar Suburban Debate,” in Imagining the American Jewish Community, ed. Jack Wertheimer (Waltham, Mass.: Brandeis University Press, 2007), 71.

5. Kapp, “Books for Jewish Children,” 548.

6. Howard P. Chudacoff, Children at Play: An American History (New York: New York University Press, 2007), 164; and Charles A. Madison, Jewish Publishing in America: The Impact of Jewish Writing on American Culture (New York: Sanhedrin, 1976), 88–89.

7. Hasia R. Diner, Hungering for America: Italian, Irish, and Jewish Foodways in the Age of Migration (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 178.

8. Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (New York: Basic Books, 1988), 11, 164.

9. Will Herberg, Protestant–Catholic–Jew: An Essay in American Religious Sociology (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1956), 43–44; emphasis in original.

10. Prell, “Community and the Discourse of Elegy,” 68–69.

11. Quoted in Theodore Frankel, “Suburban Jewish Sunday School: A Report,” Commentary 25 (June 1958): 490; emphasis in original.

12. For the changes in formal Jewish education, see Joselit, New York’s Jewish Jews.

13. Introduction, “Books for Jewish Children: The Limits of the Didactic Approach,” by Isa Kapp, Commentary 8 (December 1949): 547.

14. Johanna Ginsberg, “Publisher, 86, Still Thrills at Chance to Inspire,” New Jersey Jewish News, August 7, 2008, http://www.njjewishnews.com/njjn.com/080708/mwPublisher86StillThrills.html. Chaveri is still in print and has sold over one million copies.

15. Andy Newman, “Where the Elves Wear Yarmulkes,” New York Times, December 20, 1992, http://www.nytimes.com/1992/12/20/nyregion/where-the-elves-wear-yarmulkes.html.

16. Edythe Scharfstein and Sol Scharfstein, Paste and Play Bible. (New York: KTAV, 1957).

17. B. Scharfstein, telephone conversation.

18. Jessamyn Neuhaus, Manly Meals and Mom’s Home Cooking: Cookbooks and Gender in Modern America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 174–76.

19. May, Homeward Bound, 26.

20. Laura Shapiro, Something from the Oven: Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America (New York: Viking, 2004), 8–9.

21. Ibid., 64, italics in original.

22. Ibid., 268, 253–56.

23. Neuhaus, Manly Meals and Mom’s Home Cooking, 173.

24. Ibid., 19–22.

25. Florence S. Berger, Cooking for Christ: The Liturgical Year in the Kitchen (Des Moines: National Catholic Rural Life Conference, 1949), 7.

26. Ruth Glazer, “Where’s the Pyetroushka?” review of The Complete American-Jewish Cookbook, by Anne London and Bertha Kahn Bishov, Commentary 15 (January 1953): 106.

27. Gary Cross, Kids’ Stuff: Toys and the Changing World of American Childhood (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 147.

28. Neuhaus, Manly Meals and Mom’s Home Cooking, 173–74.

29. Alice Carroll, “Who’s Who Cooks,” Good Housekeeping (June 1950), 10–11.

30. A.I.M.S. Street, “The Gastronomical Year,” Saturday Review 37, no. 7 (February 13, 1954): 35.

31. Glazer, “Where’s the Pyetroushka?” 106.

32. Jonathan Krasner, “A Recipe for American Jewish Integration: The Adventures of K’tonton and Hillel’s Happy Holidays,” The Lion and the Unicorn 27 (2003): 351–52; and “Scharfstein Family Saga,” http://www.KTAV.com/aboutus.php.

33. B. Scharfstein, telephone conversation; Joellyn Wallen Zollman, “The Gifts of the Jews: Ideology and Material Culture in the American Synagogue Gift Shop,” American Jewish Archives Journal 58, no. 1/2 (2006): 57–77.

34. Scharfstein, Junior Jewish Cook Book, 18.

35. Ibid., 15.

36. Kapp, “Books for Jewish Children,” 548.

37. Scharfstein, Junior Jewish Cook Book, 47, 38, 18.

38. Joselit, The Wonders of America, 187

39. Scharfstein, Junior Jewish Cook Book, 33. Sukkos is the Yiddish or Ashkenazic Hebrew pronunciation of Sukkot. Out of KTAV’s desire to appeal to the entire spectrum of the Jewish community or as a result of careless editing, the Junior Jewish Cook Book followed an inconsistent pattern of Hebrew pronunciation. The cookbook alternated between the Sephardi pronunciation adopted in the Reform and Conservative movements and the Ashkenazi pronunciation used by eastern European Jews and retained by the Orthodox. While Sephardi pronunciation generally appears in the chapter titles (e.g., Sukkot), notes on the recipe pages frequently employ the Ashkenazi pronunciation (e.g., Sukkos).

40. Ibid., 21.

41. See Susan Marks, Finding Betty Crocker: The Secret Life of America’s First Lady of Food (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005).

42. Shapiro, Something from the Oven, 171–96.

43. Ellen Seiter, Sold Separately: Children and Parents in Consumer Culture (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1993), 74.

44. Street, “The Gastronomical Year,” 35.

45. Elizabeth Tilden Hildebrandt, introduction to Let’s Have Fun Cooking: The Children’s Cook Book, ed. Frances Youngren (Chicago: Moody Press, 1953), 3.

46. Frances Youngren, ed., Let’s Have Fun Cooking: The Children’s Cook Book (Chicago: Moody Press, 1953), 28–29.

47. Daniel Sack, Whitebread Protestants: Food and Religion in American Culture (New York: St. Martin’s, 2000).

48. Youngren, Let’s Have Fun Cooking, 61.

49. Scharfstein, Junior Jewish Cook Book, 11.

50. Ibid., 15.

RECOMMENDED READING

Diner, Hasia R. Hungering for America: Italian, Irish, and Jewish Foodways in the Age of Migration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Joselit, Jenna Weissman. The Wonders of America: Reinventing Jewish Culture, 1880–1950. New York: Hill and Wang, 1994.

May, Elaine Tyler. Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. New York: Basic Books, 1988.

Neuhaus, Jessamyn. Manly Meals and Mom’s Home Cooking: Cookbooks and Gender in Modern America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

Shapiro, Laura. Something from the Oven: Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America. New York: Viking, 2004.