The empire built by the United States after the Second World War was based on rules fashioned in Washington, DC, and underpinned by US-controlled institutions. The values on which it was based were then carried abroad by a series of state and nonstate actors (NSAs). It did not depend on territorial acquisition and therefore, in an ideal world, there would have been no need for US intervention in the affairs of foreign states. The institutions would ensure that other countries followed the rules and the moral force of NSAs would encourage them to do so.

In practice, of course, the world did not always operate in this way, and the US government felt obliged to intervene on numerous occasions. These interventions became increasingly frequent after the start of the Cold War, as the competition first with the Soviet Union and later with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) not only challenged the rules and institutions established by the United States but also held out to other countries the prospect of a very different world order.

US intervention took many forms. Sometimes it was direct and involved the US military; on other occasions it made use of proxy forces; often, although not widely realized at the time, the intervention was covert and not always legal even under US law. This intervention took place in all the regions—Western Europe, the Asia-Pacific, the Middle East, Africa, and the Americas—where the empire operated.

Most of these interventions succeeded in their short-term objectives, although there were a number of minor and major setbacks. Yet even the major defeats—in Angola, Cuba, Iran, and Vietnam—did not mean the empire had gone into reverse. On the contrary, the semiglobal empire (it never included the USSR and PRC) was still strong as the Cold War came to an end.

The scale of intervention was not only unprecedented in terms of the national story but almost certainly in respect of world history as well. No other country has ever undertaken such a vast commitment over such a large area of the world, and it would not have been possible without control of institutions at the global and regional level. That it needed massive military resources goes without saying, but it also required the support of the majority of the population. To secure that support, the American state depended heavily on the NSAs examined in Chapter 6.

Incorporating western Europe into the empire after the Second World War was a big challenge for the United States. Several states were empires themselves, and the United States needed these to be dismantled without alienating their governments and citizens in the process. Western Europe also needed to recover economically if it was to have any chance of remaining in the capitalist camp. And democracy needed to be promoted without risking a communist victory in any of the countries concerned.

At the heart of Europe lay Germany. Long before its unconditional surrender in May 1945, the United States had developed plans for what to do during the inevitable military occupation that would follow Germany’s defeat. As agreed at Teheran in 1943, and confirmed at Yalta and Potsdam in 1945, Germany would be divided into zones in which each of the occupying powers would have almost unlimited powers.1

The American zone (Map 11) was in the south, with the Soviet Union to the east, the British to the north,2 and a small French zone in the west3 (Berlin in east Germany was also divided among the four powers). By 1947 the US government had persuaded the British to merge their two zones and the French could be left, if necessary, to their own devices. Thus, two years after the collapse of Nazi Germany the United States was in a position to shape what would become West Germany into a protectorate in the knowledge that neither the German people nor the British government were in any position to resist US demands.

In this imperial exercise the US government was supremely successful, and West Germany was the most faithful European ally of the United States during the Cold War. US-inspired currency reform in the non-Soviet zones in 1948 put West Germany on the path to economic recovery, and the country was allowed to participate in the Marshall Plan the following year.

Map 11. Occupied Germany

Soviet resistance to the de facto partition of Germany implied by the new currency proved futile,4 and the Federal Republic of Germany was born in 1949 with a Basic Law shaped by US officials.5 By 1955 the US government had overcome the resistance of its allies and allowed West Germany to rearm and join NATO. The West German economic and political structures were now considered so stable that the United States and its allies ended the military occupation of the country everywhere except West Berlin.6

West German governments were always staunchly anticommunist, and the Basic Law made it almost impossible for communists to gain even a foothold in parliament. This was not the case elsewhere in western Europe, where communists were often popular as a result in part of the leading role they had played in the fight against fascism. Nowhere was this more true than in Greece, where communist military success had led to the launch of the Truman Doctrine in March 1947.

With the end of the German occupation in sight, a coalition government had been formed in Greece as early as May 1944 with the participation of communists. This soon crumbled, and a civil war broke out before the end of the year. The British intervened massively on the side of the anticommunists, but by early 1947—despite the death of fifty thousand Greeks—they had failed to defeat them.

It was at this point that the administration of President Harry S. Truman (1945–53) intervened and converted Greece into a US protectorate. The communists, who were supported by Albania, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia but not the Soviet Union, were defeated militarily and excluded from political life. An American Mission for Aid to Greece (AMAG) was established with extraordinary powers. A State Department directive to Dwight Griswold, head of AMAG, set the tone:

A question involving a high policy decision affecting the operations of AMAG . . . shall be . . . brought to the attention of the Department before any action is taken. . . . By “high policy” decision is meant one which involves major political repercussions. . . . Among the matters on which such high policy decisions would be required are:

a) any action by United States representatives in connection with a change in the Greek Cabinet;

b) any action by the United States representatives to bring about or to prevent a change in the high command of the Greek armed forces;

c) any substantial increase or decrease in the size of the Greek armed forces;

d) any disagreement arising with the Greek or British authorities which, regardless of its source, may impair co-operation between American officials in Greece and Greek and British officials;

e) any major question involving the relations of Greece with the United Nations or any foreign nation other than the United States;

f ) any major question involving the policies of the Greek Government toward Greek political parties, trade unions, subversive elements, rebel armed forces, etc., including questions of punishment, amnesties and the like;

g) any question involving the holding of elections in Greece.

The foregoing list is not intended to be inclusive but rather to give examples.7

This tight American control left the politicians fighting for scraps as in other US protectorates.8 Prime ministers needed to demonstrate their loyalty to Washington, DC, before they could be elected. One such was George Papandreou, but his son (Andreas) was more independent minded. When elections in 1967 looked as if they would return the elderly father to power with an important role for the son, the military intervened to establish a dictatorship. US officials were well aware of the plans but chose not to intervene.9

Subsequent support for the brutal military regime (1967–74) led to serious reputational damage for the US government,10 but it was considered at the time as a price worth paying in return for Greek loyalty during the Cold War. However, the regime overreached itself in 1974 when it overthrew the government in Cyprus and provoked an invasion by Turkey (another NATO ally).11 The junta had become a major liability, and the US government was content to see the restoration of civilian rule provided the new leaders remained loyal to the United States.

The end of the Second World War led to the formation of coalition governments in a number of western European countries in which communists took part. The most important was France, where the Communist Party had derived considerable prestige from its opposition to Nazi Germany with a big increase in membership.12 Furthermore, in the elections for the Legislative Assembly in November 1946 the Communist Party secured more votes than any other party.

Ousting the communists from the French government therefore became a top US priority after the announcement of the Truman Doctrine. One of the chosen instruments was the World Bank, which made France the first country to receive a loan subject to various conditions. In his biography of John McCloy, the American president of the World Bank, Kai Bird explained what then happened while negotiations over the conditions took place: “Simultaneously, the State Department bluntly informed the French that they would have to ‘correct the present situation’ by removing any communist representatives in the Cabinet. The Communist Party was pushed out of the coalition government in early May 1947 and within hours, as if to underscore the linkage, McCloy announced that the [World Bank] loan would go ahead.”13

Ousting the Communist Party from government in Italy would prove more difficult as a result of its enormous size.14 Although communists had been pushed out of government in May 1947,15 at the same time as in France (and Belgium), the party was well placed to win the April 1948 legislative elections. Indeed, its coalition with the Socialist Party made it almost certain that it would do so.

This prospect galvanized the US government into action using all the tools at its disposal. In addition to conventional methods (e.g., funding for noncommunist parties, increased broadcasts by the Voice of America, and mass circulation of US documentary and feature films), the campaign made use of a new technique in which Americans of Italian origin were encouraged to write to their relatives and friends in Italy warning of the dire consequences of a communist victory. To facilitate this, the US government arranged for publication of sample letters in newspapers.

The campaign worked spectacularly well, and support for the left-wing coalition collapsed in the weeks before the election. The Christian Democrats were returned to power and governed Italy for nearly fifty years. The communists were permanently excluded from power. The Christian Democrat leadership proved to be a loyal ally of the US government and Italy was effectively a protectorate throughout the Cold War with dozens of American military bases providing security.

Marginalizing communist parties was necessary, but not sufficient, if the US semiglobal empire was to be consolidated in western Europe. Communist parties garnered electoral support more for their domestic than their foreign policies. Thus, it was also necessary to encourage a noncommunist political culture that was, as far as possible, pro-American.

This work had begun in Germany as soon as the war ended, with the sponsorship of newspapers, including the highly successful Neue Zeitung. When William Benton was appointed assistant secretary of state for public and cultural relations in August 1945, he wasted no time in securing Hollywood’s agreement to “a voluntary system of consultation with the State Department in their representation of international matters.”16 This laid the basis for a long-lasting association between the US government and the film industry in the promotion of propaganda.

Not everyone was happy with these new initiatives. In April 1947 Secretary of State George Marshall wrote to Benton, “The use of propaganda as such is contrary to our generally accepted precepts of democracy and to the public statements I have made. Another consideration is that we could be playing directly into the hands of the Soviets who are masters in the use of such techniques. Our sole aim in our overseas information program must be to present nothing but the truth, in a completely factual and unbiased manner. Only by this means can we justify the procedure and establish a reputation before the world for integrity of action.”17

Marshall’s scruples and those of others were soon overcome, however, and the propaganda program (albeit not in the crude form practiced by the USSR) was put on a more secure footing in 1948 with the passage of the Smith-Mundt Act to spread “information about the United States, its peoples, and policies.” This paved the way for the establishment in 1953 of the United States Information Agency (USIA) that was then given broad global responsibility to promote US interests abroad including through the Voice of America.

The operations of USIA were in the public domain, but there was also a covert program operated by the CIA. This led in Europe in 1950 to the creation of Radio Free Europe and to the establishment of the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF). The latter in turn used CIA finances to establish a series of publications in western European countries that were highly influential (and pro-American) until their funding sources were revealed in 1966.18

When the United States started its program of “cultural diplomacy” for Europe after the war, the western states faced a grim economic future. Recovery was slow and hesitant until foreign aid under the Marshall Plan put it on a more sustainable basis. This economic assistance, however, could never be more than temporary and, indeed, ended in 1952. Under these circumstances, the administrations of Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953–61) were strongly in favor of any policies likely to promote western European economic growth.

The proposal in 1950 for a European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was therefore greeted enthusiastically by the US government. Designed by Jean Monnet, a Frenchman who had spent the war years in Washington, DC, and had become a special adviser to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1933–45), the ECSC was always seen as a prelude to a wider and more ambitious scheme for European integration. This duly occurred when the European Economic Community (EEC) was formed by six states (Belgium, France, Germany, Holland, Italy, and Luxembourg) following the Treaty of Rome in 1957.

Although the Treaty of Rome anticipated a customs union that would lead to some trade diversion at the expense of the United States, it was still supported by the Eisenhower administration on the grounds that it would promote economic growth, reduce the need for US assistance, and provide resources for national defense. In addition, the United States applied pressure to ensure there was no discrimination against inward investment by US companies, making it more acceptable to the private sector.

Integration was so successful that western Europe would in due course achieve parity with the United States on many economic indicators.19 The region might therefore have been expected to shed completely the American imperial mantle spread across it immediately after the Second World War. However, western Europe remained militarily dependent on the United States throughout the Cold War despite its growing economic strength. National security was therefore the Achilles heel of the European integration project.

The reasons for this are to be found in the perceived threat of a Soviet invasion. Always exaggerated, it was nonetheless seen as sufficiently menacing to persuade the main European countries outside the Soviet bloc (including Turkey) to join forces with the United States in NATO. Yet the only credible defense against the threat of a Soviet attack was the possession of nuclear weapons. Since these were under American control, NATO countries were ultimately dependent on the United States for their own defense and were therefore not fully sovereign.20 As David Calleo, a distinguished US scholar of transatlantic relations, explained, “The strategic defense of America and Europe may be indivisible, and NATO may be a collective umbrella, but only the American president can decide when to put it up. In short, the decisive weapons for NATO’s defense are not subject to integration, but are under direct American control.”21

NATO, despite its outward appearance, has always been dominated by the United States. During the Cold War the main commands and most of the subordinate ones were held by US military officers and member states played host to a vast array of US army, naval, and air bases.22 However, the US armed forces also built bases in some European countries considered ineligible for NATO membership. The most important was Spain, which was considered so strategically important that the Eisenhower administration was prepared to overlook its dictatorial system of government under the staunchly anticommunist general Francisco Franco.

Western Europe was transformed economically, politically, and socially during the Cold War, but it remained militarily dependent on the United States. It was, therefore, part of the semiglobal empire. This struck many Europeans as an acceptable compromise, but it could only work if the USSR was perceived as a serious threat and if US taxpayers were prepared to contribute to European defense. That is why cultural diplomacy, including propaganda, was so important for the success of the US imperial project.

BOX 7.1

THE UK-US “SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP”

British prime minister Winston Churchill, desperate to bring the United States into the Second World War, often used language designed to flatter his American audiences. This included the phrase “special relationship” to describe the historical links between the two countries, although for most of American history before the twentieth century the United Kingdom and United States had been strategic rivals.

When the United States finally entered the war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the two allies did indeed work closely together. Yet even before the war had ended, the subordinate position of the United Kingdom was clear for all to see and the United States gave no special favors to its wartime ally in the immediate postwar years.

Just how “unspecial” the relationship had become was laid bare by the US response to the British invasion (together with France and Israel) of Egypt in 1956 (see Chapter 7.3). The Eisenhower administration condemned the aggression, applied sanctions, and only reversed its position when the British withdrew their troops.

After the formation in 1958 of the European Economic Community, without British participation, the United States increasingly looked to West Germany as its key ally in Europe. Despite this, British prime ministers have continued to use the phrase “special relationship” and US presidents have generally been happy to let them do so.

The reasons for this are not hard to find even if there is little substance in the claim. For US administrations Great Britain has become a client state whose armed forces work well with the American military. Secrets are shared through an intelligence alliance (known as the “five eyes” because it also includes Australia, Canada, and New Zealand) and the United Kingdom rarely votes against the United States in the UN Security Council. For British prime ministers it is a harmless conceit that exaggerates British influence in the world and helps to assuage the loss of empire.

In reality, imperial powers—especially one with a semiglobal empire—cannot afford to have special relationships with any single country. Instead, the United States is happy to let many countries claim a special relationship as long as they do not expect special favors in return.

The United States was already a major imperial power in the Asia-Pacific region even before the Second World War started. Following the unconditional surrender of Japan in August 1945, she would acquire additional territories (see Chapter 3).23 Yet the most important acquisition was Japan itself, occupied militarily by the United States immediately after the surrender of the Japanese armed forces.

Unlike what happened in West Germany, the US government chose not to share responsibility with any other power during the Japanese occupation. To assuage Allied sensitivities, a Far Eastern Commission composed of eleven nations was set up in Washington, DC, and an Allied Council with four members (China, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the USSR) in Tokyo. However, these bodies had no executive powers and were largely ignored by US authorities.

US policy, implemented by General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), was at first driven by the doctrine of “punishment and reform.” War crimes trials were held, some 200,000 Japanese citizens were barred from public life, and a constitution was written for Japan that banned the creation of armed forces or the right of the state to conduct war.24 All this was done on the assumption that China would be the key ally of the United States in the Asia-Pacific region, relegating Japan to a relatively minor role in international affairs.

The victory of Mao Tse-tung in China in 1949 and the outbreak of the Korean War the following year forced the Truman administration swiftly to modify its plans for Japan. The country would now become nominally independent, albeit as a protectorate, following ratification of a peace treaty signed at San Francisco in 1951 by forty-eight countries,25 while simultaneously a bilateral security treaty gave the United States extraordinary powers to intervene in Japanese domestic affairs and maintain military bases throughout the country.

The security treaty was revised in 1960, but it still left the United States in a dominant position in Japan. Okinawa, where the United States had built its largest military base in the Asia-Pacific region, remained a US colony, and Japanese jurisdiction over military personnel stationed there was very limited.26 The US government also imposed restrictions on Japanese trade with Communist China until the United States itself recognized the PRC in 1971.

The dominant US position was unpopular with much of the Japanese electorate, especially the Socialist Party, but the CIA provided generous funding for the conservative Liberal Democrat Party (LDP). This helped the LDP to retain power throughout the Cold War, which provided successive US administrations with staunchly pro-American governments in Japan.

Just how unequal the relationship between Japan and the United States remained even after revision of the security treaty was revealed during the visit of President Richard M. Nixon (1969–74) and Henry Kissinger to China in February 1972. Mao and his foreign minister, Chou En-lai, used the opportunity to protest the US military presence in Japan. In the words of Michael Schaller, drawing on the memoranda of conversations between the leaders, “Nixon answered that without the security treaty and US bases the ‘wild horse of Japan could not be controlled.’ Kissinger added that the security pact restrained the Japanese from developing their own nuclear weapons . . . or from ‘reaching out into Korea or Taiwan or China.’ The US alliance provided ‘leverage over Japan’ without which, Nixon said, our ‘remonstrations would be like an empty cannon’ and the ‘wild horse would not be tamed.’ ”27

After making due allowance for the rhetoric associated with summit meetings, these conversations revealed how the wheel had almost come full circle since the Second World War when the United States had expected China at the end of hostilities to become its principal ally in the Asia-Pacific region and its partner in preventing Japan from ever again posing a threat to peace. Indeed, as early as 1943 the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1933–45) had not only committed itself to the restoration of China’s territorial integrity but was also pushing for China to become one of the permanent members of a future United Nations Security Council.

The US government did what it could to try and prevent civil war between the communists and nationalists in China starting again as soon as Japan was defeated. However, it was an impossible task and Mao’s victory in October 1949 obliged the United States to rethink its whole Asia-Pacific strategy. Even as it did so, however, the Truman administration was rapidly overtaken by events. In particular, as early as February 1950, China and the Soviet Union signed a far-reaching agreement, including a mutual defense pact in the case of aggression by Japan or “any state allied with her” (a clear reference to the United States).28

Many countries, not just in the Soviet bloc, subsequently took the opportunity to recognize the PRC as the sole representative of China. Yet the Truman administration, under enormous pressure from many quarters, refused to do so.29 Instead, the United States chose to recognize the Republic of China (ROC), Chiang Kai-shek’s administration in Taiwan, as the only legitimate Chinese government.

This momentous decision meant that Taiwan, a small island with only seven million people, would represent the whole of China in the UN and have a permanent seat on the Security Council. However, it also meant that Taiwan would become a US protectorate as the ROC had no other way of ensuring its own survival in the event of a Chinese attack. This subordinate status became clear in June 1950 when President Truman declared,

The occupation of Formosa [Taiwan] by Communist forces would be a direct threat to the security of the Pacific area and to United States forces performing their lawful and necessary functions in that area. Accordingly, I have ordered the 7th Fleet to prevent any attack on Formosa. As a corollary of this action, I am calling upon the Chinese Government on Formosa to cease all air and sea operations against the mainland. The 7th Fleet will see that this is done. The determination of the future status of Formosa must await the restoration of security in the Pacific, a peace settlement with Japan, or consideration by the United Nations.30

A Mutual Defense Treaty was then agreed on between the Eisenhower administration and Taiwan in 1954, committing the United States to defend the island in the case of attack.31 Article 7 of the treaty also gave the United States the right to establish military bases on Taiwan (there would be many). The treaty remained in force even after the PRC replaced the ROC in the UN in October 1971 and was only terminated in 1980, a year after the United States switched its diplomatic allegiance away from the Taiwanese administration to the government in Beijing.32

In the years before the Second World War, the United States had paid little attention to Korea. Following Japanese intervention in 1905, the main concern of the administration of Theodore Roosevelt (1901–9) was not to condemn Japan but to secure from her assurances that this aggressive act did not threaten the US colony in the Philippines. However, the policy changed completely with the US occupation of Japan at the end of the war. Korea—less than one hundred miles from Japan at the closest point—would now acquire strategic importance.

Korea had in fact been part of US postwar planning since at least 1943. Allied leaders had committed themselves to the independence of Korea, but then added the worrying phrase “in due course.” At Yalta, Winston Churchill, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR), and Joseph Stalin had agreed to establish a four-power trusteeship for the peninsula.33 By September 1945, however, only two powers were involved, with the USSR accepting the surrender of Japanese troops north of the 38th parallel while US forces did the same in the south.34

Both powers, unable to agree on how unification might be achieved, then moved swiftly to establish protectorates. In the south, the US occupation forces found in the aged and authoritarian Syngman Rhee a leader they could trust.35 Elections were held in 1948, Rhee was declared president of the Republic of Korea, and US forces then left. Rhee, however, remained committed to unification and a series of incidents of increasing violence culminated in invasion from the north in June 1950.

The Truman administration rushed to the defense of its protectorate, and the Korean War entered a new and more deadly phase. Helped by the temporary absence of the Soviet Union from the Security Council, the United States was able to secure UN diplomatic support and put together a coalition of sixteen countries.36 Yet a swift victory for the allies was ruled out when Chinese forces entered the war at the end of 1950.

The war ended in mid-1953 with virtually the same territorial division of Korea as when it had started. The Republic of Korea (i.e., South Korea) would now become a key part of the American empire in the Asia-Pacific region. A mutual defense agreement was quickly signed giving the United States the right to station its armed forces all over the country.37 US foreign aid and investment then poured into the country, helping to turn South Korea into a poster child for economic development. The same would happen in Taiwan.

Since North Korea had not been defeated, there were many Americans who regarded the end of the war as marking a failure of imperial policy due to US unwillingness to use overwhelming military force. The Eisenhower administration was therefore under enormous pressure to ensure the same thing did not happen again elsewhere, and it would be put to the test early on in Indochina.

Colonized by France in the nineteenth century and comprising modern Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam (Map 12), Indochina had become a Japanese possession in the Second World War. FDR at first opposed France’s plans to recover its Asian empire, but at Yalta softened his position. After the Japanese surrender in August 1945, fighting soon broke out in Indochina between Vietnamese nationalists, led by Ho Chi Minh (Box 7.2), and French forces. Although Stalin had no interest in Southeast Asia and refused to recognize Ho’s Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Truman administration gave its support to France.38

This assistance did not prevent the defeat of French forces, and in 1954 at Geneva a peace agreement was signed (the United Kingdom and the USSR were cosponsors). The outcome in Cambodia and Laos was the formation of governments acceptable to the Eisenhower administration (not itself a signatory to the agreement). Vietnam, however, was to be temporarily partitioned pending elections to be held in July 1956 with Ho Chi Minh in command in the north.

Map 12. Indochina

The Eisenhower administration now moved swiftly to impose its imperial will on the region. The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was formed on September 8, 1954, with eight members. Three countries (France, the United Kingdom, and the United States) were imperial powers in the region; two (Australia and New Zealand), anticipating a decline in British naval power, were looking to the United States for future protection;39 and one (Pakistan) hoped for US assistance in its struggle with India.

Only two members were from the region, and one of these was a US protectorate and former colony (the Philippines).40 However, Article 4, Paragraph 1, of the treaty establishing SEATO stated, “Each Party recognizes that aggression by means of armed attack in the treaty area against any of the Parties or against any State or territory which the Parties by unanimous agreement may hereafter designate, would endanger its own peace and safety, and agrees that it will in that event act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes.” 41 What this meant was revealed the same day the treaty was signed by the addition of a protocol that identified Cambodia, Laos, and “the free territory under the jurisdiction of the State of Vietnam” (i.e., the area not controlled by Ho Chi Minh) as the territories to be designated for protection against aggression.

The Eisenhower administration now had legal cover that could be used to intervene in the south of Vietnam as the French withdrew. Ngo Dinh Diem, a Vietnamese who had held office under both the French and Japanese colonial governments, was identified as a reliable future leader and engineered into the presidency of the State of Vietnam in 1955. Diem, with US blessing, then refused to hold the promised elections in July 1956 on the grounds that his government had not signed the Geneva Accords. The real reason, of course, was that Ho Chi Minh would probably have won.

Two decades later, after the death and displacement of millions of Vietnamese, the United States and its allies had been defeated in Indochina.42 Yet defeat, despite all the domestic and international repercussions, did not mark the end of American empire in the Asia-Pacific region—let alone elsewhere. The domino theory, outlined by President Eisenhower, had predicted widespread consequences if South Vietnam collapsed, but the only dominoes to fall were Cambodia and Laos. Not even Thailand, Malaysia, or Burma, all neighboring countries with left-wing insurgencies, succumbed.

Indeed, even while experiencing one setback after another in Indochina, the US government secured a much bigger and more important prize when Indonesia, the world’s fifth largest country in terms of population, committed itself to the American fold. From the late 1960s onward, it began to follow an economic development model that promoted foreign investment, trade liberalization, and regional integration from which US companies benefited enormously.

Indonesia (Dutch East Indies) had been a colony of Holland until the Second World War, when it was occupied by Japan. The Truman administration looked favorably on the Netherlands recovering its former possession for the same reasons it had done so in the case of France and Indochina (see above). However, a Dutch failure in 1948 to observe the terms of a US-brokered settlement led to a change of policy, and Indonesian independence in 1949 received US support.43

The undisputed leader of the independence struggle was Sukarno, who had no intention of replacing Dutch colonialism with a US protectorate. He manifested Indonesian autonomy not only in economic policy but also in hosting the Bandung Conference in 1955 that became the forerunner of the Non-Aligned Movement. He also cooperated with the Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI), by then the largest communist party in the world outside China and the USSR.

BOX 7.2

HO CHI MINH (1890–1969)

As European empires crumbled after the Second World War, there emerged a series of nationalist leaders who had been in the vanguard of the anticolonial struggle. Although in many cases they were communists, they were not necessarily anti-American unless circumstances forced them to be so.

Ho Chi Minh was typical of this kind of leader. Born in 1890 in a Vietnamese village, he chose to travel the world after his father was demoted from his position as a French imperial magistrate. He worked in a series of relatively menial jobs in the United States and United Kingdom before settling in France in 1919.

He joined forces with other Vietnamese activists to lobby the negotiators at the Versailles Conference to recognize an independent Vietnam. When this failed he joined the French Communist Party as a founder member before moving first to the Soviet Union and then to China.

He returned permanently to Vietnam in 1941 after the Japanese occupation and helped to form the Viet Minh as a resistance force. After the Japanese surrender, he proclaimed the birth of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam with the opening words taken directly from the US Declaration of Independence. However, neither the United States nor the USSR recognized his government (the USSR would only do so in 1950).

He tried to reach an accommodation with the newly established French government in Paris but failed, and war broke out again in 1946. It ended with the spectacular defeat of the French forces at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. In Geneva, however, he reluctantly agreed to a temporary partition of Vietnam at the 17th parallel. When the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953–61) threw its support behind the anticommunist State of Vietnam, war was again inevitable.

Ho Chi Minh did not live to see the final defeat of the United States, but he did live long enough to witness the Tet Offensive in 1968 that demonstrated the capacity of a mobile guerrilla force to defeat a superior enemy. From then on, negotiations between Vietnam and the US government only had one possible outcome.

The overthrow of Sukarno in 1965 and the crushing of the PKI by Suharto, a pro-American general, was an extremely violent process leading to an estimated 1.5 million deaths. The details are still not fully known, especially the role of the CIA, but it was a textbook intervention involving US state and nonstate actors that would be repeated in other countries.44 Indonesia under Suharto, who ruled until his overthrow in 1998, acknowledged US strategic and economic hegemony in the region in return for a free hand in suppressing domestic opponents.

The empire built by the United States in the Asia-Pacific region was therefore extensive. It did not embrace China or the Soviet Union nor, after 1975, any part of Indochina, but it was still impressive. The biggest gap was India, which stayed resolutely neutral after independence and close to the Soviet Union. Yet the semiglobal empire during the Cold War was not about territory as such and much more about influence and penetration. Even in India, US penetration was not negligible and would increase substantially once the Cold War ended.

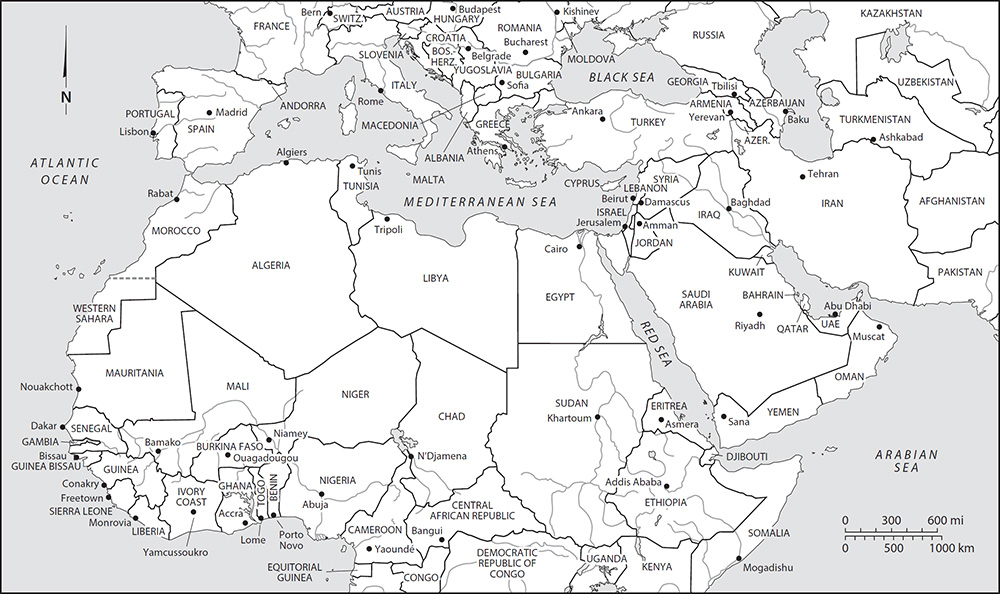

In the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa (see Map 13), unlike in the Asia-Pacific region, the United States had no territorial possessions before the Second World War. Indeed, US formal responsibilities were limited to its protectorate over Liberia in Africa. Instead, countries in these two regions were almost all controlled by different European powers as colonies or protectorates while the US presence—apart from its diplomats—was essentially limited to the investments of a small number of American firms and the activities of numerous missionaries and philanthropic foundations.

All this would change dramatically after the Second World War when US administrations set themselves a series of ambitious goals. In the Middle East45 (sub-Saharan Africa will be considered below), the first objective was to end exclusive control by European imperialists; the second was to obtain reliable supplies of energy; the third was to ensure the security of Israel; and the fourth was to prevent the USSR from gaining a major foothold in the region. These objectives required the incorporation of the Middle East into the American empire, and this is exactly what happened. However, the objectives sometimes conflicted with each other so that the US empire was never as secure in the Middle East as in other parts of the world.

By the end of the Second World War, the Italian Empire in the Middle East had collapsed so that France and Great Britain were the only imperial powers.46 French attempts to reestablish authority over Lebanon and Syria under the League of Nations mandate were thwarted by the combined efforts of the United Kingdom and the United States,47 leaving France with only Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. The last two became independent in 1956, while Algeria—legally a department of France and not a colony—became independent in 1962 after a bitter war.

That left Great Britain as the one remaining European imperial power in the Middle East. US administrations did not wish her to stay, but at the same time they were reluctant to see her depart too swiftly. Thus, British withdrawal was a long, drawn-out affair that began in 1945 and ended in 1971. As the British withdrew, the United States either stepped in to play a similar “protective” role, used proxies to do the same thing, or relied on the network of institutions and NSAs (outlined in Chapters 5 and 6) to secure compliance with US goals.

The first transfer took place in Saudi Arabia in 1945, when the Saudi and US governments signed an agreement leading to the construction of an air base close to the oil fields controlled by an American company.48 The second was in Palestine in 1948, where the United States took the lead in ending the British mandate and helping to secure the creation of the State of Israel. The third was in Iran in 1953, where a joint UK-US covert operation led to the overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq and was followed by a rapid reduction in British influence.49 The fourth was in Egypt in 1956, where a Franco-British-Israeli attempt to reverse nationalization of the Suez Canal was thwarted by President Eisenhower.50

In all these cases the decline of British power was balanced in due course by a rise in US influence. A nationalist rebellion in Iraq in 1958 then ended the British protectorate, and Kuwait became independent from Britain in 1961, limiting British responsibilities to Jordan and the small states in the Persian Gulf. The United States then replaced the United Kingdom as the hegemonic power in Iraq, Jordan, and Kuwait,51 while using Iran as its proxy in the Persian Gulf after the British withdrew in 1971. Following the Iranian Revolution in 1979, however, the United States itself took on an imperial role in the gulf.

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I was seen by American oil companies as a great opportunity despite the fact that the US economy was still largely self-sufficient in energy.52 Great Britain and France tried to keep the oil in the hands of their own companies, but American pressure forced them to allow US participation in the gigantic Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC) in 1922.53 The participants in the IPC—British, French, and US oil firms, together with Calouste Gulbenkian54—then agreed not to compete with each other in the former Ottoman Empire.55

The State Department colluded in this restraint of trade, which left excluded US companies at a disadvantage. Undeterred, Standard Oil of California secured a long-term contract in Saudi Arabia in 1933 and then sold part of its share to Texaco to defray costs. By 1938 the partnership, soon to be renamed Aramco, struck oil just outside Dhahran.

Aramco’s discovery was the most important ever made in oil history and transformed US relations with Saudi Arabia. In 1943 the kingdom was made a beneficiary of Lend-Lease assistance despite the fact it was a nonbelligerent in the Second World War. When Aramco invited two other US firms (Jersey Standard and Mobil) to participate in building the Trans-Arabian Pipeline to the Mediterranean, the Truman administration first overruled the antitrust objections of the Justice Department on national security grounds and then allowed the CIA to plot the overthrow of the Syrian government that was blocking the project.56 And when the Saudi king in 1950 insisted on a fifty-fifty profit share, the State and Treasury Departments agreed on the “golden gimmick” under which Aramco could receive a foreign tax credit to offset increased royalty payments.

By the end of the Second World War, US oil consumption was rising much faster than domestic oil reserves. This meant that the US economy, not just those of western Europe, risked becoming dependent on Middle East oil. The State Department therefore looked for new sources of oil. Outside Saudi Arabia, the largest reserves were in Iran and the covert operation against the government in 1953 provided the perfect opportunity. The Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, previously controlled by British interests, was reconstituted to provide for the participation of US firms.

The US government now had the energy security it desired. In addition, friendly governments in Libya,57 Kuwait, and the small states in the Persian Gulf region provided a warm welcome for US investments. However, the companies demanded too much, and the US government was too slow to address the problem. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) was founded in Iraq in 1960 and was able to push up oil prices dramatically in the 1970s. Governments, even those friendly to the United States, then nationalized foreign oil companies. And anti-Americanism played a key role in the Iranian Revolution that brought to power in 1979 a radical Islamist government that was determined to reduce US influence in the region. From then onward, the United States increasingly looked elsewhere for its energy security.

When FDR met Ibn Saud in February 1945, the Saudi monarch made clear his vitriolic opposition to Zionism and to the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. Mindful of this, the Truman administration at first acted cautiously on the issue. Indeed, after the UN vote in November 1947 in favor of partition, the prospect of war persuaded the US ambassador to the UN to declare partition impracticable and to back a UN trusteeship for Palestine instead.58 And when Israel declared its independence on May 14, 1948, many high-ranking US officials, including Secretary of State George Marshall, were against recognition.

Despite this, President Truman did recognize the new state within eleven minutes of its declaration of independence.59 Yet he and his successor were always careful to try and appear even-handed in the dispute between Israel and its Arab neighbors. It was not until the presidencies of John F. Kennedy (1961–63) and Lyndon Johnson (1963–69) that US policies toward Israel—on nuclear weapons, borders, settlements, and (lack of ) support for a Palestinian state60—became so one-sided.61 And these policies continued almost without interruption throughout the Cold War.

The partisan nature of US policy toward Israel has often been attributed to the power of the Jewish lobby, especially the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC).62 No one can deny that electoral considerations have always been very important in support for Israel (and may have been crucial in the case of Truman’s recognition of the Jewish state), but no imperial power has ever allowed a special interest group to impose a policy that conflicts with broader state interests. Thus, support for Israel has always been consistent with other strategic objectives.

Although Israel often irritated the United States with its domestic policies, it was a strong ally during the Cold War. Indeed, inside and outside the Middle East, Israel could be counted on to support the United States in its global competition with the Soviet Union.63 It played a crucial role in 1970 in preventing the overthrow by Arab nationalists of the Jordanian king, a key US ally. Later it would serve US interests in Africa, Central America, and South America. As the Cold War drew to a close, it was among the first countries to be awarded the title by the United States of “major non-NATO ally.”

Unlike the United States, Russia had been an imperial power in the Middle East before the First World War. Geography, especially the Black Sea, guaranteed that the Soviet Union would try to maintain a presence. Indeed, the USSR (together with the United Kingdom) occupied Iran in 1941 and tried unsuccessfully to annex northern Iran to (Soviet) Azerbaijan after the war.64 Yet the switch in the Middle East after the Second World War from British, French, and Italian hegemony to that of the United States was so swift that the Soviet Union found itself frozen out even before the Cold War started.

The overthrow of King Farouk in Egypt in 1952 by radical nationalist army officers led by Gamal Abdel Nasser gave the Soviet Union its first chance to establish a meaningful presence in the Middle East. Nasser was not anti-American, but he soon realized he would never receive from President Eisenhower the weapons he wanted to confront Israel, while his ambitious plans to construct a dam on the Nile were blocked by the World Bank acting on US instructions. The Soviet Union was then happy to fill both the military and the funding gap and signed a pact with the nationalist government in Syria as well.

Eisenhower’s swift response to the Suez Crisis, effectively siding with Nasser, gave the United States a chance to rebuild its relationship with Egypt in particular and pan-Arab nationalism in general. However, the opportunity was wasted and instead Congress passed a joint resolution in March 1957, later known as the Eisenhower Doctrine, stating that “the United States regards as vital to the national interest and world peace the preservation of the independence and integrity of the nations of the Middle East.” 65 This was a green light to intervene in the Middle East wherever there was a perceived threat to US hegemony.

The first application of the Eisenhower Doctrine came the following year. Soviet influence in the Middle East took a big step forward when radical pan-Arab nationalist regimes in Egypt and Syria announced their union as the United Arab Republic in February 1958.66 When civil unrest in Lebanon then threatened the position of the pro-American government, Eisenhower dispatched troops, naval vessels, and aircraft. The spread of pan-Arab nationalism was halted, but Nasser concluded that he needed to strengthen ties with the Soviet Union.

Lebanon was the first US invasion of a Middle Eastern country, and it prompted the Eisenhower administration to seek a more multilateral approach to restrict the Soviet presence in the region. The solution found was the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), modeled on NATO, whose Middle Eastern members were Turkey, Iran, and Pakistan.67 These countries constituted a buffer between the Soviet Union and the rest of the Middle East. CENTO was then complemented by a vast array of American military bases across the region designed to help the United States to secure its objectives in the Middle East.

Despite this, US goals in the Middle East were only partly achieved. European empires did come to an end, the United States established itself as the leading foreign power, and Israel’s survival was guaranteed. However, the United States was only able to broker peace treaties with two of Israel’s neighbors (Egypt and Jordan), and energy security proved to be elusive as a result both of oil nationalizations and OPEC. Pan-Arab nationalism and the Soviet presence in the region went into reverse after the death of Nasser in 1970, but radical Islam—especially in Iran—would prove to be a much greater challenge.

Map 13. North Africa and the Middle East

Of all the regions in the world where the United States would build its semiglobal empire, sub-Saharan Africa had the lowest priority at the end of the Second World War. The United States did retain a number of military bases and the one in Ethiopia, later named Kagnew Air Base, was expanded after 1953 providing valuable support to Emperor Haile Selassie until his overthrow in 1974. Kagnew, however, was close to the Red Sea, guarding the shipping lanes in and out of the Suez Canal, and the base was therefore closely tied to US interests in the Middle East rather than sub-Saharan Africa.68

It was not until 1949 that the post of assistant secretary for African affairs was created in the State Department, and even then it was combined with Near Eastern and South Asian affairs. The first official to be appointed was George McGhee, and in 1950 he outlined four US objectives for Africa: progressive development of African peoples toward self-government or independence; development of mutually advantageous economic relations between the colonial powers and their African colonies; preservation of the rights to equal economic treatment for all businesses in Africa; and creation of an environment in which Africans would want to be associated with the United States and its allies.69

These objectives led the United States to take a relaxed approach to decolonization by the remaining imperial powers70 (all US allies), since the US government wanted to be sure that independence would not create a political opening for the Soviet Union and a decline in economic access for American companies. And since decolonization would eventually add over fifty seats to the United Nations (roughly the same number as the founding members), it was considered imperative to limit Soviet influence to ensure that the new African states were either pro-American or at least not pro-Soviet.

By and large, these objectives were met. Decolonization started in 1956 and was completed in 1990.71 It created only a few opportunities for the Soviet Union, and even where it did—as, for example, in Guinea or Ghana—these proved not to be permanent.72 However, the reputational damage to the United States as a result of its efforts could be severe (for the case of the Congo, see Box 7.3).

The US-controlled institutions built after the Second World War proved very efficacious in keeping African countries inside the semiglobal empire. The UN generally worked as the United States had planned, with the USSR unwilling to use its veto when dealing with African affairs. International Monetary Fund and World Bank programs ensured that US companies had access to almost all African markets throughout the Cold War on a nondiscriminatory basis, and the continent was a useful source of raw materials for the US economy.73 In addition, American multinational enterprises invested heavily in mining, including strategically important mineral extraction in South Africa, and enjoyed strong support from US governments.

BOX 7.3

THE REPUBLIC OF CONGO (1960–65)

The Belgian colony of the Congo represented all that was worst about European imperialism in Africa. Thus, the decision by the colonial power to grant independence on June 30, 1960, after multiparty elections, should have marked an opportunity for the country’s advancement. This did not happen, and the United States must take much of the blame.

Within days of independence, the mineral-rich province of Katanga seceded under the leadership of Moise Tshombe. The Congolese prime minister Patrice Lumumba, a radical nationalist, pleaded for outside assistance. Belgian troops were dispatched but did nothing to put down the rebellion, as Tshombe promised to protect foreign mining interests. The Eisenhower administration responded by securing UN support for a multilateral force that also did nothing to end the secession. Lumumba then turned to the Soviet Union for support. He was soon deposed by Colonel Joseph Mobutu, a CIA asset, and murdered.

President John F. Kennedy (1961–63) inherited the problem and helped to secure the election of the malleable Cyrille Adoula as prime minister. The Katanga secession was quickly ended and Tshombe sent into exile. However, rebel factions loyal to the memory of Lumumba fought on and had gained the upper hand by 1964. President Lyndon Johnson (1963–69) then permitted the CIA to recruit white mercenaries, mainly from Rhodesia and South Africa, who committed appalling atrocities in confronting the rebels. Tshombe was then brought back from exile and installed as prime minister.

Under pressure from its allies in Africa and elsewhere, the Soviet Union finally responded with military and financial aid for the rebels. Cuba also helped, sending a small contingent of troops under the command of Che Guevara. All this assistance arrived too late, however, and the rebels were crushed.

Congo’s nightmare, grim though it had been, was still far from over. In November 1965, Joseph Mobutu overthrew Prime Minister Tshombe and imposed a kleptocracy upon the country, whose name he changed to Zaire in 1971 (it would be renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo after his overthrow in 1997). He remained on good terms with the United States throughout his long period of rule.

Yet there was one country whose independence represented a major setback for the United States, and that was Angola. Nationalists had launched in 1961 a guerrilla war against Portugal, the colonial power ruled dictatorially by António Salazar from 1932 to 1968. Portugal, however, was a key American ally as a result of allowing the United States to operate an air base in the Azores, and the United States was therefore reluctant to support any of the guerrilla factions.74 When Salazar’s successor was overthrown in 1974, the Angolan faction that had Soviet support, the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA), then defeated its rivals in a civil war and Angola declared its independence in 1975.

The United States, anxious to avoid a Soviet “victory,” then gave its backing to the defeated factions that also had the support of the apartheid regime in South Africa.75 As the Angolan government came under attack from South African troops, Cuba—without informing the USSR—responded to a request for military assistance.76 Its troops helped to secure a series of stunning victories that should have brought the civil war to an end. However, the United States and apartheid South Africa continued to support the anti-MPLA factions, which plunged Angola into a further ten years of conflict.77 This put the United States firmly on the wrong side of history in Angola, since it had both failed to support decolonization and also cooperated with apartheid South Africa.78

By the end of the Second World War, the US government exercised such enormous leverage over the other states in the Americas that they were assigned a low priority in peacetime planning. However, the start of the Cold War drew US attention to those countries where left-wing parties and trade unions had gained influence as a result of the wartime US-Soviet alliance. Policy then changed very quickly and governments in the region came under pressure to change course.

The impact of the change in policy was swift. Communist parties were declared illegal in most countries. Brazil and Chile severed relations with the Soviet Union in 1947. In the same year US pressure undermined the coalition in Bolivia that governed with the support of a Marxist party and contributed in the following year to the military coup in Venezuela that overthrew a progressive government. A major offensive was launched by the US labor federation AFL-CIO against left-wing trade unions and new anticommunist confederations were established. The British government also played its part, sacking in 1953 the left-wing administration of Cheddi Jagan in the colony of British Guiana.79

From the US perspective these measures were so successful that communist influence had been virtually eliminated in the Americas by 1954. There was, however, one important exception: Guatemala. The Central American republic, whose long-serving dictator had been overthrown in a popular revolt in 1944, had held its first free presidential elections the following year. The winner was Juan José Arévalo, who cautiously began to tackle Guatemala’s legacy of social backwardness and capitalist privilege.

Inevitably this brought him into conflict with US-owned companies, including the United Fruit Company (UFCO), which owned vast areas of land and enjoyed a virtual monopoly over railways, telegraphs, and ports.80 The Truman administration then applied intense pressure to try and force Arévalo to change course. This included an embargo on arms sales, no Point Four foreign aid, and the threat of a veto against any loans from the World Bank.81

President Arévalo, to the surprise of many, survived this US onslaught. His successor, also elected in free elections, was not so fortunate. Colonel Jacobo Arbenz was not a communist, but he did legalize the Partido Guatemalteco de Trabajo (PGT), purchased arms secretly from Czechoslovakia, and passed legislation (Decree 900) to expropriate the largest farms, including those owned by UFCO. These actions earned him the fury of the US establishment. The Council on Foreign Relations, in a confidential report, captured the mood: “The Guatemalan situation is quite simply the penetration of Central America by a frankly Russian-dominated Communist group. . . . There should be no hesitation . . . in quite overtly working with the forces opposed to Communism, and eventually backing a political tide which will force the Guatemalan government either to exclude its Communists or to change.”82

Arbenz was driven from office in 1954 by an invasion force from Honduras organized by the CIA, and Carlos Castillo Armas was installed as a puppet president.83 Guatemala was then condemned to three decades of civil war and the loss of more than 100,000 lives. At the time, however, the covert operation was hailed as a great success. The Eisenhower administration was then free to concentrate on other regions of the world, confident that international communism had been purged from the Americas.

This confidence proved to be premature. Herbert Matthews’s articles in the New York Times in February 1957 had drawn attention to the guerrilla movement in eastern Cuba led by Fidel Castro, and events thereafter moved swiftly. President Eisenhower, who had supported Fulgencio Batista as a bulwark against communism, took exception to the increasingly brutal methods employed by the Cuban dictator to defeat his opponents and suspended arms sales in mid-1958. However, US diplomatic efforts to find a suitable replacement for Batista failed and Castro entered Havana triumphantly on January 3, 1959.

Castro then implemented a government program very similar to that adopted by Arévalo and Arbenz in Guatemala, with land reform as its centerpiece. Eisenhower responded exactly as he had done a few years earlier and authorized the CIA to organize an exile force to invade Cuba. Castro, however, had learned the lessons of history and was well prepared. The exiles were defeated at the Bay of Pigs in April 1961, by which time President Kennedy was in power, and later that year Castro announced that the Cuban Revolution was Marxist-Leninist and allied to the Soviet Union.

This was a huge blow to US prestige, and it was only partially reversed by the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 when the Soviet Union agreed to withdraw its nuclear missiles from the island in return for a US promise not to invade Cuba. Kennedy recognized early on in his administration that US policy in the Americas needed to change and to pay more attention to the economic and social grievances that underpinned revolutionary upheaval. As a result, the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) began operations, the US Agency for International Development (USAID) was started, and the Alliance for Progress (ALPRO) was launched.84

Castro’s survival, albeit subject to a trade embargo and many other restrictions, meant that US administrations were now much more sensitive to any leftward shift in the region and would react quickly in the event that it happened. The first test, however, came not in Latin America but in the Caribbean colony of British Guiana where Cheddi Jagan, returned to “office but not power” in 1957, had been reelected in 1961.85

Jagan was determined to take the British colony to independence as soon as possible. Frustrated by the lack of cooperation from the British government, he secured an interview with President Kennedy in October 1961. The Kennedy administration, however, concluded that Jagan was dangerously left-wing and set out to destabilize his government with the connivance of the British authorities. All state and nonstate instruments were employed including the CIA, the AFL-CIO, the US Information Service and the Christian Anti-Communist Crusade.86

The key to promoting instability was a general strike that was then used by the British government as an excuse to rewrite the Constitution of British Guiana and impose a new electoral law based on proportional representation. Fresh elections were then held in 1964. Although Jagan’s party won the largest number of seats, it no longer commanded a majority. The governor then invited Forbes Burnham, leader of a rival party, to form a government and independence was granted two years later. Guyana (as it was now called) accepted US hegemony but suffered two decades of economic incompetence, human rights abuse, and mass emigration.

The defeat of Jagan in 1964 appeared to the Johnson administration to remove the last challenge to US hegemony in the Caribbean outside of Cuba. Most of the islands were still either US colonies or territories of European powers that were members of NATO.87 Among the numerous British colonies, only Jamaica and Trinidad & Tobago had become independent, and both wanted good relations with the United States.88 François “Papa Doc” Duvalier, Haitian president for life, had survived a half-hearted US attempt to unseat him and was happy to play the anticommunist card in return for US tolerance of his dictatorial regime.

That left only the Dominican Republic, where the United States had intervened in 1961 by authorizing the assassination of President Rafael Trujillo and again in 1963 by supporting the overthrow of President Juan Bosch.89 A triumvirate was then established that met all US requirements. However, when the new regime was itself overthrown in April 1965 by young officers and rebels allied to Bosch, President Johnson ordered an immediate invasion by US troops. The intervention was in due course supported by the OAS and Joaquín Balaguer, a close ally of Trujillo, was installed as president the following year.

One of the few Latin American countries to send troops to the Dominican Republic in support of US intervention was Brazil. This was in return for the support the army had received from the Johnson administration the previous year in the military coup against President João Goulart. It was not the first time the US administration supported the military in removing a democratically elected head of state, nor would it be the last. However, it was a rare intervention in Brazil, a country that from its independence in 1822 had been a staunch supporter of US policy and even of the Monroe Doctrine.

Goulart had made many enemies among the Brazilian elites. He had adopted progressive social policies, including land reform, and had nationalized a number of foreign-owned companies. He also favored junior officers in the armed forces over their more conservative senior colleagues. None of this was sufficient to justify US support for a military coup, but those close to President Johnson convinced him that Brazil was moving closer to Cuba and could even fall under the influence of the PRC. The United States then employed the usual array of covert instruments, including funding for civil society groups opposed to the government, but even more important was the signal to the rebellious officers that a coup would enjoy US support.

This signal would be employed again in Chile nearly a decade later when President Salvador Allende, elected by popular vote in September 1970 and endorsed by Congress the following month, was overthrown in a military coup on September 11, 1973.90 The plotters, including General Augusto Pinochet, had kept US authorities informed of their plans and knew they would not suffer sanctions if they were successful.

The fall of Allende was the culmination of a ten-year campaign by US agencies to undermine him and isolate him politically. Allende, a member of the Chilean Socialist Party, had come close to winning the 1958 presidential election. He vociferously opposed the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1961 and US authorities became concerned he might win the presidency in 1964. A major program of covert action against him was unleashed. In the words of a US Senate select committee, “Covert American activity was a factor in almost every major election in Chile in the decade between 1963 and 1973. In several instances the United States intervention was massive. . . . The 1964 presidential election was the most prominent example of a large-scale election project. The Central Intelligence Agency spent more than $2.6 million in support of the election of the Christian Democratic Candidate [Eduardo Frei]. . . . More than half of the Christian Democratic candidate’s campaign was financed by the United States, although he was not informed of this assistance.”91

The campaign was very successful and Allende was easily defeated in 1964, but similar efforts failed to avert his victory in 1970. There then began a campaign to discredit Allende and destabilize the Chilean economy that was orchestrated by the 40 Committee, an interagency body chaired by Henry Kissinger to oversee covert CIA activities. It included a veto on new loans from US or US-controlled institutions as well as funding of opposition political parties and local media.92

The message from the fall of Allende in 1973 was clear. The US government would not stand in the way of military intervention if its strategic interests could conceivably be threatened. Military coups then followed in Argentina and Uruguay, leaving most of South America in the hands of authoritarian figures sure to protect US interests. This was similar to the situation in Central America, where the fall of Arbenz in 1954 had appeared to remove any threat to US concerns.

The overthrow of Anastasio Somoza by the Sandinistas in Nicaragua in July 1979 therefore took US authorities by surprise.93 President Jimmy Carter (1977–81) was not unaware of the opposition to Somoza, whose family had ruled Nicaragua with US support since 1936, but he had assumed that a moderate alternative to both Somoza and the Sandinistas could be found. Carter tried to protect US interests without destabilizing the new government but his successor, President Ronald Reagan (1981–89), had very different ideas.

BOX 7.4

THE US INVASION OF PANAMA (1989)

There were seven US invasions of Panama in the twentieth century, and the last occurred in December 1989. At the time there was a civilian president, but power was in the hands of General Manuel Noriega, commander of the Panamanian Defense Forces.

Noriega had been of great assistance to numerous US agencies and was considered a CIA asset. However, he had overstepped the mark by providing sensitive US intelligence information to Cuba and Libya. Details of his drug-dealing and money-laundering activities were then revealed to Seymour Hersch and published in a series of articles in the New York Times in July 1986. He was indicted by a US court in February 1988.

When Noriega refused to step down from his position as Panama’s de facto ruler, his days were numbered. He survived two unsuccessful coup attempts but could do nothing in the face of the US invasion in which the number of fatalities may have reached several thousand.

The invasion was authorized by President George H. W. Bush (1989–93), who as director of the CIA (1976–77) had worked closely with Noriega. The invasion was justified in the following terms:

Safeguarding the lives of U.S. citizens in Panama.

Defending democracy and human rights in Panama.

Combating drug trafficking.

Protecting the integrity of the Torrijos–Carter Treaties.

The fourth justification was probably the most important, as it reflected the long-standing US strategic interest in the Panama Canal. However, the second and third were harbingers of things to come (the first can be ignored, as there were already eleven thousand US troops in the Canal Zone). US interventions did not end with the Cold War, but they could no longer be justified in terms of an alleged Soviet threat.

Reagan’s campaign against the Sandinistas, although ultimately successful, took the United States into some very dark places that seriously undermined public confidence in the American imperialist system. It involved covert support for the anti-Sandinista contras that broke congressional laws and involved US agencies in major human rights abuses.94 It also included the mining of ports and the destruction of shipping in a sovereign state with which the United States was not at war.95

US operations (overt and covert) helped to wreck the Nicaraguan economy, and the Sandinistas were easily defeated in the 1990 presidential elections. By this time the US government had also ensured there would be no military victory by left-wing guerrillas in Nicaragua’s neighboring countries,96 had dispatched the US Marines to Grenada in 1983,97 and had invaded Panama in 1989 (Box 7.4). Central America and the Caribbean, other than Cuba, were once again firmly under US control as the Cold War came to an end.