LEVELS

A level usually corresponds to a unit of place (and time) in the progression of a game. Each level normally has a setting that differentiates it from previous levels. Sometimes called a map, or even a world, a level is thus a stage in a video game as it is simply a recognizable subspace inside the more general game world. Levels are distinguished by various characteristics: environment, typography, enemies, objectives, difficulties, etc. They are “discrete virtual locations containing tasks that must be accomplished before players can advance” (Laidlaw, 1996, p. 122).

In game design theory, a level usually refers to the different worlds constructed by the level designer that the player must explore and complete in order to finish a game. Level design is a crucial phase in game design. Several designers, critics, and scholars have written about the importance and functioning of the game level design, such as Chris Crawford (1982), Andrew Rollings (1999), Cliff Bleszinski (2000), Steven Chen and Duncan Brown (2001), Richard Rouse (2005), Phil Co (2006), Jeannie Novak and Travis Castillo (2008), and Rudolf Kremers (2009). In his book, Rouse defines the level as such:

[The level] refers to the game-world of side-scrollers, first-person shooters, adventures, flight simulators, and role-playing games. These games tend to have distinct areas that are referred to as “levels.” These areas may be constrained by geographical area (lava world versus ice world), by the amount of content that can be kept in memory at once, or by the amount of gameplay that “feels right” before players are granted a short reprieve preceding the beginning of the next level.

(Rouse, 2005, p. 450)

Level design is much more than the creation of playable maps; it is the consideration of many parameters such as the gameplay in general, the development and progression of the player, or the credibility of the map in the sole purpose of providing a fun experience. In game industry, level design is realized by the collaboration of various trades (designers, programmers, animators, sound designers, etc.) under the responsibility of the level designer. They all must meet the objectives set by the game designer while meeting gameplay criteria.

Level Design and Genre

The peculiarity of level design, and of game design as a whole, comes mainly from the fact that it differs more or less considerably depending on the genre. Each video game genre has its particularity about the design of a game level. Level design does not work the same way as it does for a platform game, an (action) adventure game, a fighting game, or a role-playing game (RPG), just to mention a few genres that have been significant in video game history. Nevertheless, all these genres emphasize the importance of level design as the main creation of the game space. While this space is not always explorable, as in fighting games for example, the use of space by the gamer is fundamental to the gameplay.

Platform Games

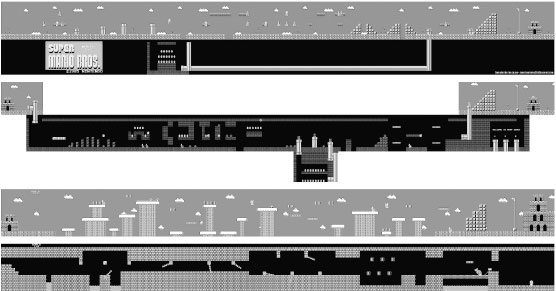

In platform games, the main emphasis is on the player’s ability to control the movement of his/her avatar. The avatar must normally use platforms (by jumping on them) to explore space. Platform games offer a simple goal that usually requires the completion of several levels filled with traps and enemies to avoid or eliminate. The levels’ difficulty increases as the player advances through the game, as well as the enemies’ strength, down to the “final Boss.” For example, the exemplar of these games, Super Mario Bros. (Nintendo, 1985), contains eight different worlds, which are themselves divided into four sub-levels (stages) that must be traversed in order to complete the game (Figure 13.1).

Since Super Mario Bros., the genre usually relies on a simple quest to accomplish, stretched across a world many times the size of a screen, represented by side-scrolling, with power-ups (or increased power bonuses) that improve, usually temporarily, the features or abilities of the avatar.

Figure 13.1 The four stages or sub-levels in the first world of Super Mario Bros. (1985).

Source: VGMaps.com: The Video Game Atlas.

As a very popular genre during the 1980s, platform games have had a great influence in the evolution of game level design, even during the advent of 3-D games, which have mixed platform game mechanics with other genres (such as first-person perspective action games, action-adventure games, etc.). The strong point of this genre, which has helped develop the way three-dimensional space is interactively represented, is based on the gradual unfolding and discovery of the game space and a simple video game mechanism influenced by the theme of the game (the enchanted kingdom of Super Mario Bros., the interplanetary travel of Super Mario Galaxy (Nintendo, 2007), the interior of a brain in Psychonauts (Majesco, 2005), etc.).

Action-Adventure Games

Distinctively, in the adventure game genre exploration and investigation are essential tasks needed to solve the various puzzles encountered in each level. Action-adventure games have added an active dimension (fighting, jumping, racing, shooting, etc.), becoming the most varied genre, as for example in the rich exploration of different worlds and levels in the Tomb Raider series (Eidos, 1996–present). This genre is strongly attached to action and adventure movies, hence the highly cinematographic or narrative aspect of most of these games. Since action-adventure games are based on multiple worlds or areas to discover one-by-one and narratively separated in chapters, the division of a game world into levels was a crucial step in the development of game space, from its architectural structure (in which objects are placed) to its aesthetic style.

Fighting Games

Fighting games involve a very different type of level design from other video game genres, since gameplay is based solely on the close combat of two belligerents inside an arena. The space is not a world to explore, but rather a circumscribed area in which the axial movements are the key to gaining the upper hand over the opponent. While space is strongly bound to the execution of combat, it also serves as a thematic structure to position the fight within a particular visual and narrative background, for example, based on the nationality (or other socio-cultural stereotypes) of the enemy that one fights, as is the case in the Street Fighter series (Capcom, 1987–present). Even more than games based on exploration, space in fighting games contains visual spectacle, while its static aspect makes this space more of a “tableau” than a level. Developers use clichés associated with each theme represented in order to clearly mark the location and the theme of the fighting environment.

RPGs

The term “level” is also used in RPGs, but with different meanings. It can refer to the degrees of difficulty in the game, to the amount of strength and experience that a character has (a fifth-level fighter versus a second-level wizard), or to the depth of a dungeon (the third level of a dungeon). RPG mechanics are also distinct from other genres. The exploration of a vast space is critical, but space is not necessarily divided into levels. The way the space is designed, whether or not the player can explore every elements of this space, is to convey a sense of openness—a map or territory to explore and unfold. The leveling system, in which characters need to level up in order to beat more powerful enemies, is borrowed from tabletop RPGs. Strongly reminiscent of the tabletop RPG Dungeons & Dragons (Gygax and Arneson, 1974), game challenges are mostly in the form of quests, including fighting against monsters (often in a distinct screen or space) and managing an economy of weapons, magic, and party (of controllable characters and non-player-characters). The environments are mostly generic, with the usual dungeons, castles, and medieval cities associated with the genre of heroic fantasy.

The Functions of Level Design

Since level design depends strongly on a game’s genre, and thus has a different role to play in each of them, we can infer that level design has three main functions: a structural or architectural purpose (tied to spatial design), a ludic role (defined by gameplay efficiency and segmentation), and a narrative function. These functions are obviously not exclusive to each other, as level design is a complex component of a game system containing multiple layers of meaning, as I will demonstrate by explaining each function separately.

Spatial Design

Like urban space, the possibilities of actions in a virtual world are not without limits. Behind these spaces, there is always a “designer” who places objects in space and creates the settings. In the city, it is the urban planner or the architect. In video games, it is the level designer, in which his/her creative tasks are often compared to the practice of architecture (see for instance von Borries, Walz, & Böttger, 2007).

Lev Manovich (2001) emphasizes two key aspects regarding the question of space in video games: the navigation of three-dimensional space and level structure (pp. 244–273). The video game world of DOOM (id Software, 1993) follows the usual conventions of video games by its constitution in a dozen of levels. The game Myst (Cyan, 1993), meanwhile, contains different “worlds” (islands known as “Ages”) that do not need to be visited in any particular order during the game, making them different from a traditional level structure that implies some kind of progression. In fact, these two games exemplify the two main ways to construct the game world in “levels.” As we have seen in the previous section, which also served to underscore the importance of space in game design, while most action and platform games are divided in levels that are quite similar to each other with respect to their structure and appearance, the worlds of adventure and games of emergence, such as Myst, are distinctly different. Level design can then be as much the creation of an enclosed and segmented space as an open and exploratory space.

Most action games are still linear, where the main purpose is just to go forward and fight enemies or bypass them in order to accomplish the required objectives. The most effective way to build this type of space is to develop a labyrinthine environment or a map constructed of several rooms or separate areas demarcated by concrete (gates, transportation, etc.) or metaphorical (screen changes or cut-scenes that indicate a new territory or level to explore) boundaries. In order to properly lead the player in this environment, certain areas cannot be accessed or are blocked by “physical” or even “invisible” walls (Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Smith, & Tosca, 2008, p. 97). The action is also scripted, where the passage of an avatar in a specific location triggers a new action (for example, enemies suddenly appearing) or an event (such as a cut-scene). The environment and all the characters encountered during the game (such as the movements of monsters run by artificial intelligence) are thoroughly prepared and planned during level design.

As such, a world can’t be built in isolation. Every facet of the video game development process is organically interrelated with the requirements of others. In a game, an artist explains in Steven Poole (2000), “[t]he early levels are all meadows and open spaces to get the player comfortable with the character” (p. 212). The terrain is designed expressly to optimize gameplay. Therefore, another crucial step in level design is the design of gameplay. So that the players can immerse themselves in the game world, the entire space must be consistent. There must be a harmony between the objects’ dimensions, the achieving path, and the game style.

One of the most fundamental aspects of the game level for the design of gameplay is that it allows a “segmentation of gameplay,” as explained by Zagal, Fernández-Vara, and Mateas (2008). Segmentation of gameplay is for the three authors a useful concept to capture the function that design elements such as levels, bosses, and waves (of enemies) fulfill in games. Put simply, it refers “to the manner in which a game is broken down into smaller elements or chunks of gameplay” (Zagal, Fernández-Vara, & Mateas, 2008, p. 176). Segmentation of gameplay can manage and control the development of the gaming experience through level design:

Segmentation of gameplay … is not new or particular to videogames. However, videogames have greatly extended the varieties of segmentation, making the concept richer and more sophisticated. Specifically, videogames have introduced new vocabulary referring to gameplay segmentation. For instance, words such as level, boss, and wave refer to particular ways of segmenting gameplay that have become essential in describing and analyzing videogames. These words, however, are also used informally, so that novel forms of segmentation are sometimes conflated under these general terms.

(Zagal, Fernández-Vara, & Mateas, 2008, p. 178)

According to these authors, there are three general modes of gameplay segmentation: temporal, spatial, and challenge segmentation. Temporal segmentation concerns the limitations, synchronization, and/or coordination of the activity of a player during a period of time, while spatial segmentation is the virtual space of the game divided into sub-locations. Some terms used to describe particular forms of spatial segmentation include “levels,” “maps,” or “worlds,” as we have already discussed. The challenge segmentation occurs when the sub-units are presented as autonomous and successive challenges for the player, usually involving a growing difficulty. In an adventure game, for example, a series of puzzles need to be solved by the player to go further, where each puzzle solved allows him/her to encounter a new one. Most (contemporary) games include multiple forms of segmentation that are interrelated and/or occur synchronously.

Regarded historically, the majority of video game worlds were rarely revealed as a continuous whole, but rather as a set of distinct sub-spaces explored separately, even if such sub-spaces have been wider than the screen. Consequently, what is important in determining segments of games is whether these sub-spaces are distinguished as separate places, or if there are any gameplay restrictions or differences between each location. In such cases, the player really has the feeling of traversing the space in parts, and not as an open and unique space. Of course, most actual games attempt now to offer the player the impression of a continuous, unsegmented, and therefore more “realistic” space (for example in the Grand Theft Auto series, Rockstar Games, 1997–present, especially since the ground-breaking third installment, Grand Theft Auto III, 2001). However, a non-spatial segmentation does not prevent challenge segmentation, while the gameplay division in several distinct missions still gives the impression of game segmentation. In this sense, the notion of “level” is wider than its spatial implementation, since the temporal and challenge segmentation must also be taken into account in designing a game world.

As Zagal, Fernández-Vara, and Mateas also argue, the specificity of the level is reflected in the discontinuity of the gameplay and in the different spaces between each level. Often, the changeover from one level to another is emphasized through the use of transitional screens or cut-scenes. Between two levels, a cut-scene (which will usually advance the plot) is customary, if not the presentation of scoreboards, a save screen, or just a loading screen for the next level. However, this discontinuity must not affect the spatial cohesion, where the art of level design is tied to the creation of diverse aesthetic motifs, which are required to stay in touch with the general theme of a game: “As parts of a gameworld, levels are often grouped together by representational themes, (e.g., ‘ice’ or ‘lava’) or by particular aspects of gameplay (e.g., ‘flying’ or ‘driving’)” (Zagal, Fernández-Vara, & Mateas, 2008, p. 183).

This differentiation fits within a coherent overall structure. For example, as its title suggests, Super Mario Galaxy takes place in the outer space. Mario must traverse from galaxy to galaxy to retrieve stars that will allow him to save Princess Peach. Within this general theme, each galaxy that Mario must conquer has its own specific level with its unique aesthetic motifs and game mechanics. For example, in the galaxy “Honeyhive” (the second level of the game), Mario must acquire a bee costume (a power-up) to access flowers and eventually meet the queen bee, who will give him stars. This tool is then used to confront the “Boss” level, a giant insect (Bugaboom) that can be defeated by flying and jumping on his back to crush him.

In addition to their specificity and their aesthetic coherence, the series of levels exemplifies a form of challenge segmentation, since each level becomes increasingly more difficult and usually takes more time to finish. Completing each sequence, one after the other, gives the player a sense of progression. This feeling is particularly evident in the early arcade platform games (that provided exemplars of level-based structure for all the action/adventure games that followed). For instance, in Donkey Kong (Nintendo, 1981), each game screen, which is its own level, represents a part of a skyscraper (the game is explicitly inspired by King Kong) where the player, through his/her avatar (Jumpman, which subsequently became Mario), must “climb the building” step by step in order to reach the upper level (the Boss level) where s/he can rescue the princess by defeating Donkey Kong. Since they are all part of the skyscraper, each level is “higher” than the previous one, giving a clear “sense of progression” while maintaining a “sense of spatial relationship between them” (Zagal, Fernández-Vara, & Mateas, 2008, p. 184).

Although levels in games such as Super Mario Galaxy and Donkey Kong are different, they are still connected by unique gameplay features. The abilities developed when using tools or devices during a level (including power-ups) are normally useful for the following levels. Challenge segmentation, where the player must solve a series of autonomous and distinct challenging situations (perceived by the player as tests or separate tests), is inseparable from spatial segmentation in level-based video games.

Specific forms of challenge segmentation include puzzles, boss challenges, and/or waves of enemies as in Space Invaders (Taito, 1978). The most obvious challenge segmentation is the presentation of a series of riddles or puzzles to be solved before the next ones become available. This form of segmentation is common to adventure games, where it is usual for these games to be organized as a series of puzzles whose solutions allow the player to advance in the game world. By contrast, the boss challenge is usually the culmination of the game, representing a unique and highest form of challenge (but in relation with the different skills acquired previously during the game). Beating the final boss, and thus the game, gives the player a feeling of (challenge) accomplishment, but also more often than not, a feeling of (narrative) closure.

Narrative Function

As mentioned by Zagal, Fernández-Vara, and Mateas (2008, p. 195), the technological evolution of video games (directly related to its evolution in both form and content as an increasingly narrative medium) has allowed new forms of gameplay segmentation. Gameplay is now often subdivided into narrative elements, as required by dramatic storytelling (e.g. subdivisions into chapters, acts, scenes, etc.). In addition, the forms of gameplay segmentation already discussed above are increasingly presented to the player in a narrative context. For example, we can easily conceive today of any kind of simulation games with narrative settings. Regardless of the historical period in which a particular title fits, the gameplay can remain essentially unchanged (for example, in a racing game, it consists essentially of the driving of vehicles). However, adding a narrative requirement to the game (as is the case, for example, in the evolution of the Need for Speed series (Electronic Arts, 1994–present), especially since the release of Need for Speed: Underground in 2003, clearly influenced by the success of the movie The Fast and the Furious (2001)), can add not only to the immersion or simply to the fun of the experience, but also to the understanding of the game’s objectives.

The narrative elements of video games, which are mostly influenced by literary and cinematographic counterparts, are usually placed in a specific game level structure. A video game narrative usually contains a general structure or a set of rules that define not only its gameplay, but also its fictional environment as a segmented one, such as repetition of a series of actions in each level (in order to accumulate more points or to master the rules) creating a sense of narrative loops or the unfolding of the adventure story in steps that needs to be completed one by one and in a particular order (with the usual cut-scenes placed at appropriate moments).

During its evolution, the medium of video games has established specific structures in the development of its gameplay (and also its narrativity). The level structure acts as an “architectural block” in the spatial design of a game, as well as a restrictive and segmented structure for the creation of gameplay, and as a narrative strategy for the unfolding of an interactive story. Even if this segmented structure is more difficult to detect today (unlike its explicit presence in early arcade games), it is nevertheless still present. However, the triple architectural, ludic, and narrative functions of levels in video games seem clearly to be evolving towards an “ideal” where the three could—maybe one day—be intertwined seamlessly.

References

Bleszinski, C. (2000). The art and science of level design. GDC 2000 Proceedings, 107–118.

Chen, S., & Brown, D. (2001). The architecture of level design. GDC 2001 Proceedings, 167–175.

Co, P. (2006). Level design for games: creating compelling game experiences. Berkeley, CA: New Riders Publishing.

Crawford, C. (1982). The art of computer game design. San Francisco: Osbourne-McGraw-Hill.

Egenfeldt-Nielsen, S., Smith, J. H., & Tosca, S. (2008). Understanding video games: the essential introduction. New York and London: Routledge.

Kremers, R. (2009). Level design: concept, theory, and practice. Wellesley, MA: A. K. Peters.

Laidlaw, M. (1996). The egos at id. Wired, 4(8), 122–127, 186–189.

Manovich, L. (2001). The language of new media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Novak, J., & Castillo, T. (2008). Game development essentials: game level design. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar Cengage Learning.

Poole, S. (2000). Trigger happy: videogames and the entertainment revolution. New York: Arcade Publishing.

Rollings, A. (1999). Game architecture and design. Tucson, AZ: Coriolis Group.

Rouse, R. (2005). Game design: theory and practice. Plano, TX: Worldware Publishing.

von Borries, F., Walz, S. P., & Böttger, M. (Eds.). (2007). Space, time, play: computer games, architecture and urbanism: The Next Level. Berlin: Birkhäuser.

Zagal, J. P., Fernández-Vara, C., & Mateas, M. (2008, April). Rounds, levels, and waves: the early evolution of gameplay segmentation. Games and Culture, 3(2), 175–198.