DEATH

Video games simulate real-life experiences in many respects even though the environments in which we play are often based in a fantasy world, a science fiction world, or in historical settings. Games can be used as a laboratory for experiences, some we will never encounter in real life, and some we have to face in the future. As death is an experience we cannot speak about after we have faced it, it is a concept that is very difficult to grasp. Fingarette (1996, pp. 1–5) describes death as an empty concept that has no meaning in itself but needs to be interpreted by its rituals, symbols, and contexts in which it is embedded to make it meaningful. He describes death and its rituals and contexts as a building on which many perspectives are possible: “There are as many correct perceptions of that building as there are perspectives from which to view it” (p. 85). Death itself seems to be at the center of this building, hidden from the outside. Those of us who grew up in a Western culture, and have not experienced war, have rarely been present at the moment of death of a close friend, family member, or even a beloved pet. Dying is something that happens behind closed doors, often in special institutions but rarely in one’s own bedroom or living room with family members all around one. At the same time, while this experience is being hidden from our everyday life, death and the fascination with it can be observed in digital media, such as the coffin cam online on the See Me Rot website, which claimed to have installed a camera in a coffin, filming the decomposition of a dead body and sending the data out to everyone interested watching it via the Internet; or the Facebook application If I die, which claims to offer a way to send comments and post on your friends’ Facebook walls long after your death. Both the coffin cam and the If I die application are discussed online to be hoaxes. Whether the coffin cam did exist and film a real body, or the If I die application is really in development, is less relevant for this essay than the fact that they are representations of new ways of approaching death. Another example is the iDeath calculator available via iTunes calculating the user’s predicted date of death. Avatar-based video games do not only let us watch dying and death but we actively are involved in the death of our own avatar or those of others. This opened a never-ending debate in the media based on the visual aesthetics of death and killing in games. This debate clearly shows that before even asking about the function of death in video games, a moral statement and judgment is sometimes made without an understanding of the complexity of this topic.

This essay reflects on death, dying, and suicide in video games and points out the functions that these activities have in many video games. Indeed, we experience the death of our own avatar while playing when we kill or are being killed by non-player characters and other players’ avatars.

Death is not only a topic in video games but in board and card games as well. The best known board game is probably the war game, chess. However, many other board and card games are played around questions of death and dying (Lange, 2002, p. 94), such as the board games Game of the Goose, backgammon, or the card game War.

The difference between those rather abstract representations in board games and card games and the representations in video games is that in the latter we are explicitly confronted with death. As graphic card games now offer more and more film-like representation, violence, death, and dying are also more clearly represented and not in only an abstract way. While playing chess, we also attempt to kill our opponent’s army, yet this does not lead to heated discussions about violence as the killing in a first-person shooter does.

An observer just watching (and not playing) could compare the visual experience with a movie and wrongly align the experience of watching a scene in game to his or her prior filmic experience. In story-based games the player might identify with a nonplayer character and mourn his or her death as in Final Fantasy VII (Yoshinori Kitase & Hironobu Sakaguchi, Square, 1997) the moment Aerith is killed. This moment has been described on the IGN Entertainment website, a provider for reviews and discussions about video games, as number 1 of the top 100 video game moments:

Death happens all the time in videogames. In Call of Duty it’s a slap on the wrist, in Dark Souls it’s education, in Pac-Man it’s another coin for the machine. In Final Fantasy VII, though, one death is a genre-defining moment: Aerith Gainsborough’s.… what hit so hard about Aerith’s death … was the fact that you, too, had known her, had invested all that time and energy in her, only for her to be suddenly taken away. There is no moment in gaming’s emotional journey from kids’ entertainment to modern storytelling medium that has endured as strongly as this.

(http://www.ign.com/top/video-game-moments/1)

Aerith’s death is the loss of a game character who was central to the storyline of Final Fantasy therefore her death has been deplored by many players. However, while a movie and a story-based game intend its observers to emotionally connect to the protagonists and immerse them within the narrative, many other video games, such as multiplayer games, do not ask for immersion and empathy in the same way. As in the playing of chess, such games ask instead for a strategy to win and to control the action.

The implementation of death into games has a specific function. In the case of arcade games in the 1970s, the implementation of death has economic reasons as Lange (2002, pp. 96–97) shows. As the investment in arcade machines was very high—they were very expensive—the investors looked into opportunities to make money out of them; therefore playing time has to be restricted. This happened by increasing the difficulty of the game after a few minutes and led to “game over” or to the death of the player’s avatar.

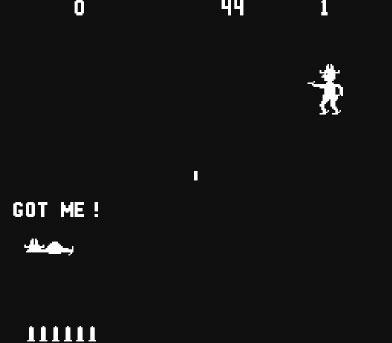

The implementation of death in mainframe games, such as those on the PLATO system such as Maze War (Steve Colley, 1974), an early first-person shooting game in which players could interact with each other online, has a different function. Even though the avatar in this game is not a full human body but a human eye, being shot by another player leads to “game over.” “Game over” can be different from the avatar’s death as it ends the game for the player, but death is not necessarily involved. The player is being pushed out of the game, which has an effect on the ludic experience, but this does not mean that the game’s narrative is changed. But the death of the avatar has an effect on the game’s narrative. The avatar in early games was not an anthropomorphic figure or part of a storyline, but often only a spaceship or a cannon; “death,” then, was the loss of a spaceship. The spaceship’s passengers were not visible, and the question as to whether a spaceship required a commander within the game world was not relevant. Central to gameplay were objects that the player could manipulate during interaction with the machine. Concepts as “life” or “death” were used only metaphorically. The first game showing the death of a human-like avatar was Gun Fight (Midway, 1975). When the avatar died, the text “got me” appeared (Figure 38.1).

“Got me!” reminds us of children’s games as hide and seek or chasing each other, but not of killing. If we want to speak about the death of an avatar in Gun Fight, it is more like “playing dead” than being dead. The player could continue playing by inserting another coin into the machine. Therefore, there is no finality regarding the death of the avatar in Gun Fight or other arcade games. This tradition can be traced to recent video games in which the avatar can also resurrect on the spot or from the last save point so that the player can continue playing.

Figure 38.1 An avatar dies in Gun Fight (1975).

The representation of death in video games has changed a lot since rather abstract human stick-figures were being shot or run over. The graphic representation of human figures has become more and more photorealistic and cinematic representations of death and killing are now the norm in action games produced for adult gamers. The violence being explicitly shown in these games can be shocking as in the survival horror action game Dead Space (EA Redwood Shores, 2008) and its sequels Dead Space 2 (2011) and Dead Space 3 (2013). While Dead Space is situated in a science fiction world and the enemies attacking are aliens, other games show fights between humans and situate these fights in cities such as New York in Max Payne 1 (2001) and 2 (2003) and Sao Paulo in Max Payne 3 (2012; all Rockstar Studios). The introduction of slow motion in these fight scenes in the Max Payne series (so-called bullet time) made it possible to show the flight path of a bullet in slow motion but this also has an impact on the visual representation of the body hit by this bullet. The player can watch the bullet penetrating the body and blood surging from the wound in detail, and in slow motion as well. Fictional game worlds, as in science fiction or fantasy, put the representation of death into a sphere distant from the player’s experiences outside of the game. The photorealistic representation in action games such as Max Payne 3, however, are set in the simulation of a real city and deal with such topics as the divide between the rich and the poor, corruption, and organ harvesting, and are therefore closer to the player’s real world. What sets these action games apart from players’ real experiences is the fact that in all these games the player’s avatar can only survive by causing the death of others. While the death of the non-player characters is usually final, the death of the avatar is not.

Dying

When we play a new game and are not skilled yet, we are forced to watch our avatar die over and over again. These deaths, then, have a didactic function and take place on the ludic level of the game and not on its narrative level. Dying leads to “game over” when the player is pushed out of the game but he or she is still may be able to re-enter and replay the game. Playing a game means, in most cases, to develop our avatar further, to learn to control the game, and to adapt our actions to the affordances of the game software. This can be compared to a process in which the player is asked to improve his or her skills, or, to put it differently, to submit to the rules of the game, internalize them, and follow them. Internalization of the game rules is rewarded with staying alive. Grodal (2000, p. 203) has shown that “the sense of realism is enhanced because the player’s control is not absolute but relative to his skills.” While the player partly gains control, the game controls the activities of the player. The possibility of replaying a sequence to improve one’s own gameplay does not only give the impression that the player gains control but it also controls the actions of the player and establishes a functional circuit between player and game. Staying alive is rewarded by being able to enter the next level, improving skills, gaining experience points, or reaching a higher rank in a game. Dying results in punishment by losing experience points or the rank and the status related to it, paying for damaged equipment or for a soul healer to retain the full functionality of the avatar in game again. Following Nohr (2012, p. 67),

[t]he player subordinates to a routine of repetition that is on the one hand technical (insofar as the program defines the parameters that have to be reached in order to display the visual representation of a successful jump) and on the other hand also reaching in to fields of social and cultural meanings. The player subordinates willingly to a procedure of optimizing his or her actions—a self-optimization.

Playing a video game includes several decisive moments a player has to solve by using a trial-and-error method. In a situation where the player makes a wrong decision or lacks the skills to solve a problem, the avatar dies. This does not end the avatar’s existence since games, as we have previous noted, offer a “replay” function through resurrection or revitalization of the avatar. The experience of a player with a video game can be described as a playful encounter of death and dying. A player plays through several deaths of his or her avatar. These are symbolic deaths comparable to those in comics or movies, as we do not speak about physical bodies here or about an irreversible state.

Using an avatar as a tool to play a game helps the player to become immersed into the game world and become a part of it. The avatar’s death turns out to be a disruptive factor for the player’s immersion, and the game’s narrative experience, in those games in which a narration is integrated. An identification of the player with the avatar breaks down in the moment of the avatar’s death (Neitzel, 2008, p. 158). The player reacts to this with irritation or a shrug of shoulders, depending on what the in-game consequences look like. For most single-player games, dying means to go back to the last save point, and gained points and items are lost and need to be gained again. For a multiplayer game, such as a massive multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG), experience points and sometimes also equipment is lost, or at least becomes broken and needs repair. Furthermore, the death can affect the group a player plays with, and all group members might die as result of the death of one avatar or lose points. The death of the avatar is a loss, but mainly a loss of time and money. Both are annoying, rather than a reason for mourning.

Challenge Mortality

The omnipresence of death and dying in video games can be seen as based in the computer’s ontology. If we understand the computer as a simulation machine, then we can challenge the concept of mortality. While symbolic representations of death in novels or movies allow for an imaginary examination of death and dying and philosophical questions of mortality, video games differ in their death simulations. They hinder this reflection and examination because of their replay function, as this highlights repeatability without consequences. What games add, however, is the observation of one’s own death, even though it is just one’s own avatar dying. As the player is still able to resurrect and continue playing, death is connected to control and becomes an insubstantial obstacle, as reflected in gaming practices such as the committing of suicide in games. The number of suicide gaming videos on YouTube shows how the experience of dying is central for some players, who try to find out how many ways there are to die in a game. These documentations are combined with an entertaining soundtrack and funny comments. This can be described as counterplay, a concept that is used to describe a way to play a game against its rules or against the intention of the designers. Counterplay means using the built-in game algorithm not for solving tasks given by the game, but using the game for something else than what it was designed for. Instead of fighting monsters or another team of players and submitting to the game’s affordances, players can use the game environment for different performances, taking over control and exploring how else the game environment can be used. Being in control, while deliberately facing the loss of control, is central for in-game suicides. This can result in pleasure, as is shown in suicide gaming videos.

Serious Ends

While most video games do not challenge the player with thought-provoking philosophical questions about mortality, Preloaded Studios’ free online web-game The End (2011) offers a different approach. Mainly addressing players in their teenage years, the game is designed to make its players think more about complex questions concerning mortality. The game starts with the avatar’s death and gives different options as to what might follow after death. Death is a central topic in this game and players are asked to reflect on death instead of playing with it as we do in most video games. The player is not only asked to collect “death objects” and will come across “keys of knowledge” represented by quotes, such as Somerset Maugham’s “dying is a very dull, dreary affair and my advice is to have nothing to do with it.” Later on, the player is asked to answer questions such as “Is there such a thing as a cause worth dying for?” and “Can we understand what death is actually like?” The answers to questions about death help to construct an explanation of death based on the player’s decisions.

The End is not the only game that treats death and dying differently from most video games. The discussion about death in video games being final under the term “permadeath” is well known in gaming communities. A few games are exceptional as they include permadeath of an avatar—as in Minecraft (Markus “Notch” Persson, 2009), Diablo 2 (Blizzard Entertainment, 2000), and Diablo 3 (Blizzard Entertainment, 2012) in their hardcore mode. This is discussed by players, not so much from the perspective of a loss of someone close (death and mourning), but rather as a loss of a toy you paid a lot for and invested a lot of time in developing it further. The fact that this toy is taken away from the player leads to anger and discourages further play. Especially for games that have been purchased or paid for with a monthly fee, this is considered a loss of money, and all the hours invested in levelling an avatar are lost if permadeath is applied. In Diablo 2 and 3, the loss is a loss of an avatar, though there are still other avatars to play with, so this hardcore mode does not lead to a final end of playing the game. This is the case for other games as well in which the player plays with a group of avatars and permadeath only affects one avatar but not the whole group of avatars, so that the game can still be played. As Bartle has shown “existing virtual world culture is anti-PD [PD = permadeath]” (Bartle, 2003, p. 444). Permadeath is experienced as a penalty and treated as such. It is not treated in a way we would react to death in our lives outside of games. Permadeath adds a new rule to the game, which denies replay. This also means that the possibility to improve one’s own gameplay is denied.

Conclusion

The presence of death adds to the experience of a game as a world, and its worldness (Klastrup, 2008; Krzywinska, 2008). The functions of death in games ask for a deeper analysis. Death and dying as punishment, and staying alive as reward seem awkward, if we consider games a simulation of real-life experiences. Reward and the experience of success could also be achieved differently, for example, by exploring the game world or in online games by becoming part of a game community. This relates back now to the opening of this essay in which I tried to point out that the simulation of death in a safe and seemingly controlled environment has an important function for the individual and can be compared to similar symbolic representations of death. The experience of death in a safe environment without any serious, lasting consequences and its reversibility gives the impression that we are in control and can live through an experience that in real life is neither controllable nor reversible. It is the fascination and fear of death that seems to be unbearable in real life when we are confronted with the loss of a loved one, but that, when it occurs in-game to one’s own avatar, does not have a major impact emotionally.

The player is able to interact with a concept that many people do not like to contemplate in real life and observe their “own” death from the perspective of an observer. Dying in video games is the result of a failure and can be controlled by improving one’s own playing skills. Whenever an avatar dies in game, the player’s immersion within the game world is disrupted and the constructedness of the world is foregrounded. This offers the possibility to understand the way we conceptualize our real life, its rules, conventions, and its limitations as well.

References

Bartle, R. (2003). Designing virtual worlds. San Francisco: New Riders.

Fingarette, H. (1996). Death: philosophical soundings. Chicago: Open Court.

Grodal, T. (2000). Video games and the pleasures of control. In D. Zillmann & P. Vorderer (Eds.), Media entertainment: the psychology of its appeal (pp. 197–212). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Klastrup, Lisbeth. (2008). What makes World of Warcraft a world? A note on death and dying. In Hilde G. Corneliussne & Jill Walker Rettberg (Eds.), Digital culture, play, and identity: a World of Warcraft reader (pp. 143–166). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Krzywinska, Tanya. (2008). World creation and lore: World of Warcraft as a rich text. In Hilde G. Corneliussne & Jill Walker Rettberg (Eds.), Digital culture, play, and identity. A World of Warcraft reader (pp. 123–142). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lange, A. (2002). Extra life: Über das Sterben in Computerspielen. In Museum für Sepulkralkultur (Ed.), Game_over: Spiele, Tod und Jenseits, Ausstellungskatalog, S. (pp. 93–104). Kassel: Arbeitsgemeinschaft Friedhof und Denkmal e.V.

Neitzel, B. (2008). Selbstreferenz im Computerspiel. In W. Nöth, N. Bishara, & B. Neitzel (Eds.), Mediale Selbstreferenz (pp. 119–196). Cologne: Halem.

Nohr, R. F. (2012). Restart after death: self-optimizing, normalism and re-entry in computer games. In M. Ouellette & J. Thompson (Eds.), The game culture reader (pp. 66–83). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.