ONTOLOGY

In game studies, ontology is the study of the nature of games: their mode of being or existence, and of variation within their domain. However, this is vastly complicated by the fact that game studies is constituted of a great variety of methodological and disciplinary approaches, many of which do not study the same type of phenomenon (e.g. an ethnographic vs. a technological approach). So the preliminary steps of any game ontology must be to first establish a meta-ontology (or more precisely, a meta-game-ontology), and then place itself within it. Since a comprehensive list of approaches (and due discussions of these) would demand much more space than can be allocated here, this approach will be fairly general, with many omissions and simplifications.

The term ontology may refer to the general study of being and existence, or a particular theory of being and existence, but also to the meaning used in computer science, that of a formal mapping of an empirical domain (e.g., a railroad system), and the construction and use of such descriptions in implementing simulation—or control-software that accurately models behaviors, objects, and their relations within this domain. Game ontologies can have similar motivations: they can be highly specific formal models of the design space of games, or they can try to answer the general questions: What are games? What do they consist of? Where are they in relation to similar phenomena? Thus, we have at least two different types of game ontologies: (1) Formal or descriptive ontologies, asking what are the functional characteristics and components of game objects, and the relations between them; and (2) existential ontologies asking what are games and what kind of existence does a game have.

Both types of ontologies presume that games exist, but neither is dependent on a formal definition of the concept of game in order to be meaningful. So the question of whether it is possible to define the category of games formally, introduced and answered in the negative by Wittgenstein (1953) and challenged (Suits, 1978) but never refuted, need not concern us here. “Games,” like “texts” and “planets,” is a historical term and not a scientific one, and trying to change it into a theoretical term would probably do more harm than good, were it to succeed. As Wittgenstein pointed out, we can still talk about games successfully without a definition, and, let me add, we can still describe games through formal models. The only risk is the possibility that we also will describe things that probably are not games, but this overproductivity matters not as long as the models convincingly describe the phenomena people call games.

The most basic ontological concern regarding games is whether the word refers to an object or a process. Games are both object and process (a combination of states not dissimilar to the duality of language: langue/parole, paradigm/syntagm etc.), but the phrase “a game” will refer to either one or the other, not both. In most contexts, “I bought a game” refers to an object and “I watched a game” refers to a process, and we are seldom if ever in doubt as to which refers to what. But without a specific empirical context, however, as when game researchers from different disciplines meet and use the word “game,” the exact sense being used can be hard to determine, and pseudo-disagreements often occur. The reason is that some game disciplines, for instance game psychology, have a process as their primary focus, while others, such as aesthetic approaches, have an object, and no one realizes that the other is speaking about a different type of phenomenon.

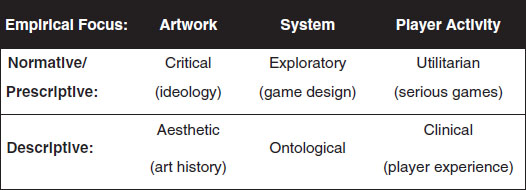

In games studies, additional focal bifurcations exist: within the object perspective there can be a focus on the game as artwork (commodity or artifact) vs. the game as system; and both the object-centered and process-centered approaches can be divided into normative and descriptive: those who try to improve the studied phenomenon (better games, or better lives) and those who merely try to understand it.

A third complication may occur when a language is used that does not distinguish between “game” and “play” but uses the same word for both. Thus, the original versions of Wittgenstein (German), Huizinga (Dutch), and Caillois (French) use the same word for game and play, and it is up to their translators to decide which one to use. Roger Caillois ([1958] 1961) seems to offer a remedy for this in his distinction between ludus and paidia, but in doing so he changes the original Latin and Greek semantics of these words with rather unfortunate consequences, since outside his book the words still refer to historical practices not compatible with his more restricted meanings, such as the Ludi Romani. The famous Roman festival games typically contained both rigid and free gameplay, and so the word “ludus” cannot be reduced to Caillois’s restrictive meaning without simultaneously ignoring one of the most influential play cultures in history.

Formal Game Ontology

Although Johan Huizinga ([1938] 1955) is generally recognized as the instigator of modern studies of play, Caillois ([1958] 1961) should be given credit for being the first to attempt an ontological study of games. While Wittgenstein’s contemporary observation that games cannot be formally defined is a more fundamental insight (1953), Caillois attempted to create a structural model from which we can describe game genres not by their physical attributes and material practices but by their mental aspects. What for Wittgenstein is primarily a very useful example for the philosophy of language, is for Caillois a unique and separate empirical field of “infinite variety” ([1958] 1961, p. 11) for cultural research, and as such it is in need of its own system of classification and categorization. Caillois’s system is a two-dimensional grid where one axis is a dialectical continuum between the aforementioned paida (turbulent, unrestrained, childlike play) and ludus (goal-oriented, methodical, rule-regulated play), and the other consists of the four main categories agôn (competitive), alea (chance-based), ilinx (vertiginous), and mimicry (play-acting). Naturally, Caillois’s influential description has been met with numerous rewritings (and misinterpretations), critiques and alternatives, but remains highly resilient after more than five decades. We can also see echoes of similar and earlier dichotomies in the paidia / ludus pair: Schiller’s ([1795] 1957) naive and sentimental (the direct, natural vs. the reflective and modern), and, as pointed out by Dan Dixon (2009), Nietzsche’s Dionysian and Apollonian. A later parallel can be found in Michael Apter’s reversal theory (1989), which includes the two opposed modes telic (goal-oriented) and paratelic (playful, now-oriented).

A final delimitation of game ontology can be to describe what it is not, but which constitute nearby or complementary areas of game research. The most obvious limitation of an ontology is that it must be descriptive rather than prescriptive, objective rather than normative. Any approach that is focused on changing the world may (and should) still have an ontology as its basis, but it can only contribute to ontology as a side-effect since its main target must be what does not yet exist. If we add to this the main different foci of game research, that of game as artwork, game as system, and game as player activity, we get a six-field table (Figure 59.1).

Most game research can be placed in this table, either in a single location or straddling two nearby slots. For instance, ontological research will or should be combined with, and supporting, most if not all the other fields, or it can take place by itself as basic research. Thus, the critical or aesthetic study of games will benefit from being based on an ontological game model, as will clinical research on the media effects of games, and game design and “serious games” design in their attempts to understand which elements work best and how they relate.

A Brief Overview of Formal Computer Game Ontologies

An early attempt to map the possibility space of so-called “interactive fiction” (another name for text-only adventure games) was made by Richard Ziegfeld (1989). Ziegfeld listed a number of technical and interface elements (“simulation,” “interaction” etc.) and suggested how they could be combined. While his terms were typically too imprecisely defined and too overlapping to form a truly useful ontology, he deserves recognition as probably the first computer game ontologist, inspiring later work such as Aarseth (1995). The latter is an attempt to build a comprehensive, generative model that can describe games’ formal features along a number of dimensions, such as perspective (vagrant, omnipresent), teleology (finite, infinite), goals (absolute, relative), and so on. Like Ziegfeld’s model, it produces a multidimensional space where all games and possible games can be described, but more care is taken to make the dimensions independent and orthogonal. The model can be used for both game design, by identifying new combinations of structures that can result in new games, and game genre analysis, by classifying a number of existing games according to the model, and then analyzing the data set with an explorative method such as correspondence analysis (see Aarseth, 1995).

Figure 59.1 Six research perspectives on games.

Inspired by Christopher Alexander’s concept of Design Patterns, Björk and Holopainen (2004) have approached the question of mapping game structures into a large number of game design patterns, design elements that can be found in a number of games. One example is the pattern paper, scissors, rock, which can be found in games where the player must choose a weapon or tactic that has strengths and weaknesses relative to the other players’ choices. Their method is highly specific and yields a large number of patterns, which may be beneficial for game designers looking for inspiration, but can be challenging to apply in an analysis of a specific game. Jan Klabbers (2003) proposes a top-down ontology where a game consists of three main elements—actors, rules, and resources. Mateas et al. (www.gameontology.com/index.php/Main_Page) is an ongoing project to map structural game elements hierarchically. It has four top-level categories (Interface, Rules, Entity Manipulation, and Goals), and a large number of sub-entries. This ontology is mainly a selection of examples, and the hierarchy is at times less than intuitive (e.g., why is Entity Manipulation a top-level entry, and not placed under Rules?).

The main problem facing game ontologists is that of choosing the level of description for their game models. Games can differ by minute details and most differences would be too particular to generalize into a model. Similarly, the list approach taken by the game design patterns project invites an endless list of patterns; there is no natural stopping point in the model. Another problem is that ontologies that are useful for one purpose may be much less so for another. A general-purpose game ontology may therefore end up as much less useful than one that has been constructed with a special purpose in mind.

What’s in a Game: A Simple Model of Game Components

Even within the narrower domain of games in virtual environments, there are tens, maybe hundreds, of thousands of games that are somehow formally different from each other. A game such as Tetris (Alexej Pajitnov, 1985) has almost nothing in common with World of Warcraft (Blizzard Entertainment, 2004), or with Super Mario Sunshine (Nintendo, 2002). Whereas media formats such as print or film have certain well-defined material characteristics that have remained virtually unchanged since they emerged, the rapid evolution in games and game technology makes our assumptions about their media formats a highly unreliable factor to base a theory on. We simply cannot assume that the parameters of interface, medium structure, and use will provide a materially stable base for our observations, the way the codex paperback has remained the material frame for students of literature for more than five hundred years. In ten years’ time, the most popular games, played by tens if not hundreds of millions of people, may have interfaces that could be completely different from the MMOGs (massively multiplayer online games) of today. The lack of a stable material frame of reference is not necessarily a problem, however, since it actually allows us to see beyond the material conditions and formulate a descriptive theory with much larger empirical scope, both synchronically and diachronically. Indeed, a trans-material ontology of games may also be used to frame phenomena we normally don’t think of as games, for example art installations and other forms of software. In my theory of cybertext (Aarseth, 1997), I presented a general model of what I called “ergodic” communication, which included all works or systems that require active input or a generative real-time process in order to produce a semiotic sequence. I used games as a main example of these “cybernetic texts.” As I pointed out, fundamental for these systems is that they consist of two independent levels, the internal code and the semiotic, external expression (1997, p. 40). This distinction was inspired by Stuart Moulthrop’s (1991) observation that hypertexts contain a “hypotext,” the hidden, mechanical system of connections driving the choices presented to the hypertext reader. This duality is the most fundamental key to the understanding of how representational games work, how they signify, and how they are different from other signifying systems such as literary fiction and film:

[W]hat goes on at the external level can be fully understood only in light of the internal. […] To complicate matters, two different code objects might produce virtually the same expression object, and two different expression objects might result from the same code object under virtually identical circumstances. The possibilities for unique or unintentional sign behavior are endless.

(Aarseth, 1997, p. 40)

This structural relationship should not be confused with the notions of form and content, that is, syntax and semantics, or signifier and signified. Both the internal code and the external skin exist concretely and in parallel, independently and not as aspects of each other. To conflate surface/machine with signifier/signified is a common misunderstanding made by semioticians and other aesthetic theorists who are only used to studying the single material layer of literature and film. Together with gameplay, we propose that semiotics and mechanics are the key elements of which any virtual environment game consists (Figure 59.2).

Figure 59.2 A simple division of the empirical object, into three main components.

Mechanics and semiotics together make up the game object, which is a type of information object, and when a player engages this object the third component, gameplay, is realized. The game object should not be confused with the material object we buy in a game store. This is a software package that may contain many kinds of information objects besides one or several games. For instance, when using Max Payne (Remedy Entertainment, 2001), we are exposed to animated movie sequences and comic book sequences in addition to the gameplay. To use a cliché, game software often contains “more than just a game.” The game object is the part of the software that allows us to play. The semiotic layer of the game object is the part of the game that informs the player about the game world and the game state, through visual, auditory, textual, and sometimes haptic feedback. The mechanical layer of the game object (its game mechanics) is the engine that drives the game action, allows the players to make their moves, and changes the game state. The tokens or objects that the player is allowed to operate on can also be called game objects (plural); these are all discrete elements that can enter into various permanent or temporary relations and configurations determined by the game mechanics. Game objects are dual constructs of both semiotics and mechanics. Some games may have a player manifested in the game as a game object, typically called an avatar. Other games may simply allow the player to manipulate the game objects directly through user input. A typical example of the latter is Tetris, where the game objects are blocks of seven different shapes, and which the player manipulates, one by one, with the simple movement mechanics of move left or right, or turn left or right.

To illustrate the duality of semiotics and mechanics, consider the two simple Internet games Dean for Iowa (Bogost and Frasca, 2004) and Kaboom: The Suicide Bombing Game (fabulous999, 2002) (Figure 59.3).

Figure 59.3 Two skins, one system, one game?

In Dean for Iowa, the player must flash an election campaign sign at the right moment to attract the maximum number of people’s attention. In Kaboom: The Suicide Bombing Game the player must detonate the bomb at the right moment to kill and injure the maximum number of people. In both games, the player’s character can run bi-directionally on a busy street where people walk back and forth at different speeds, and the points are scored in the same way, by pressing a button at the optimal time. Mechanically, these two games are identical. In terms of semiotics and meaning, they could hardly be more dissimilar. Even so, are they the same game, despite the very different references to the world outside?

As we move from observing the games as played by others and become players ourselves, the different visuals fade into the background and the engagement with the game becomes an obsession with the game goals and mechanics, a narrowly-targeted exercise where the number of points scored becomes the dominant value, not the sight of convinced voters or dead, mangled bodies. While suicide bombing might be too disagreeable for many players, scoring points by symbolically killing virtual enemies is typically not. So the reason why normal, psychologically healthy people as players are able to enjoy symbolic killing is that the internal value system of scoring points takes precedence over the violent symbolism of the external reference, especially in games where the achievement, and not the painful and mortal consequences, is in focus.

The mechanical layer of a game is, of course, not completely devoid of any ideological meaning, but it will, through players playing, create its own ideological discourse, through a reinterpretation of the game’s semiotics, which de-emphasizes the ideological meanings and interpretations that non-players will produce upon seeing the game semiotics for the first time.

Neither would it be correct to suggest that the production of game meaning is a deterministic process uni-directionally produced by the game system. Players typically fight and disagree over games as well as in them, and this conflict discourse is an integral part of what a game is. Gameplay is inherently ambiguous (Sutton-Smith, 1997) and playing a game is a constant renegotiation of what playing means and how important it is. Games are real to the players playing, but in different ways, and the ambiguous reality of games allows different interpretations. “It is just a game” is the eternal protest heard when player A feels that player B takes the game too seriously. But player A would not have felt the need to remind player B of this seemingly trivial fact, if it had been trivially true at all times. A game is never “just a game,” it is always also a ground or occasion to discover, contest, and negotiate and also construct what the game really is, what the game means.

Existential Game Ontology

Finally, there are the existential problems that games and gameplay raise, which we may consider in the dim light of such vague terms and concepts as fictional and real. Are game phenomena a kind of fiction? Are they more than one kind? Can they be real? If so, in what sense? Or should we simply introduce a third category, the virtual, to save ourselves from facing this thorny issue?

For Caillois, games are based on either rules or fiction. Agôn and alea games are ruled, and mimicry games are fictional. We may readily concede that “mimicry,” in the cases of theater and role-play, is typically fictional in its reference, but does it have to be? A play on stage can be fictional, but it can also be documentary. Mimicry (mimesis, representation) is neutral on the documentary–fictional continuum, and if we employ a classic definition of fiction such as Dorrit Cohn’s, where fiction is “literary nonreferential narrative” (Cohn, 2000, p. 12), we can easily distinguish between fictional and documentary narratives. We can even extend her definition to any nonreferential discourse, and include paintings, sculptures, and other figurative, image-type nonreferential signs. All it takes for these to be fictional is that there exists no referent in our non-fictional world. However, if such a referent exists, the discursive object or sign must be classified as non-fictional, or documentary. So Caillois is incorrect in linking mimicry only with fiction and the fictional; a theatrical play may be documentary as easily as it is fictional. For representational games, this means that as long as the game objects refer to events and existents in our world (e.g., in our history), they do not fictionalize but document. Fullerton (2008) proposes an excellent discussion of documentary games. She distinguishes between generic and specific simulations; a generic simulation is referring to a type of object, while a specific simulation is referring to a particular, historical token object. In Fullerton’s view, documentary simulations and games do not have to refer to specific objects to be documentary; they can also refer to generic objects (e.g. a type of airplane) and the resulting simulation is still documentary, not fictional.

But what about objects in non-documentary games, or objects that simply do not have a historical referent, such as an orc or a magic pearl? With regard to objects such as these, two oppositional schools can be said to exist: ludo-fictionalism and ludo-realism. The ludo-fictionalist school, inspired by Kendall Walton’s radical and influential Mimesis as Make-Believe (1990), one the one hand, sees games, game objects, and game-worlds as fictional, as “props in a game of make-believe.” For them, the rules may be real, but the discursive elements and actions are fictional (Juul, 2005; Bateman, 2011). The ludo-realist school, on the other hand, sees game objects and game events as real, or at least closer to reality: “Simulations are somewhere in between reality and fictionality: they are not obliged to represent reality, but they do have an empirical logic of their own” (Aarseth, 1994, p. 79, see also Aarseth, 1997, 2007). Evidence for the ludo-realist position was produced by Edward Castronova’s (2001) seminal observation that the in-game currency of the massively multi-player game EverQuest (1999) had a real-world exchange rate, and therefore was indistinguishable from any other (real-world) currency. This renders EverQuest-money very different from fictional money, or even from ludic money found in board games such as Monopoly (Charles Darrow, 1935).

Moreover, players typically treat important in-game objects much the same way they treat their extra-ludic property, including sometimes going to extremes such as murder when they are robbed in-game (BBC, 2005). It is not uncommon for game objects traded online to reach price-levels similar to quite expensive commodities, such as (physical) jewelry or cars. Not only does this make the ludic objects different from fictional objects, but it places them on an entirely different ontological level, in the same category as digital word processing documents (which we treasure despite their non-tangential mode of existence) and money in our digital bank accounts. The signs generated by the games’ interfaces, unlike those of fictional media productions, are in fact referential, and therefore non-fictional: they refer to the information objects (e.g., cellular automata) maintained by the game engine.

The personal nature of our relationships with ludic objects, like our relationship with say, sports equipment, indicates strongly that we are not dealing with fictional props in the Waltonian sense. A prop is a physical object that refers to a fictional object, and whose existence and capabilities are secondary to those of the fictional object. But there is no need for make-believing when players shoot at each other in Counter-Strike (Valve Corporation, 1999); they are manipulating nonphysical, informational guns that shoot non-physical, informational projectiles and when their avatars are hit, they do not have to make-believe that they are eliminated. This happens, factually, in the game machine, entirely independent of the players’ imagination, just like a pinball when it drops below the reach of the flippers. The game software determines the characteristics of the objects players use, and they cannot change these by make-believing them to be something else, any more than theatre audiences can change a stage prop by imagining. Unlike the stage prop, however, the use-relationship between player and object is primary.

Existential game ontology challenges the already unclear notions of fictional and real, and especially the border between them. But this seems primarily a problem for the theorists of fiction and those who use the concept without a critical consideration of its limits, especially when other concepts could be used instead. Game theorists, and more importantly, players, do not seem to need a definition of fiction to grasp the ontology of games and gameplay.

References

Aarseth, E. (1994). Nonlinearity and literary theory. In G. Landow (Ed.), Hyper/text/theory (pp. 51–86). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Aarseth, E. (1995, July). Text, hypertext or cybertext? A typology of textual modes using correspondence analysis. Paper presented at ALLC/ACH 1995, UC Santa Barbara.

Aarseth, E. (1997). Cybertext: perspectives on ergodic literature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Aarseth, E. (2007). Doors and perception: fiction vs. simulation in games. In B. Perron (Ed.), Intermediality: history and theory of the arts, literature and technologies, playing, 9 (Spring), 35–44.

Apter, M. (1989). Reversal theory: motivation, emotion and personality. New York: Routledge.

Bateman, C. (2011). Imaginary games. Winchester: Zero Books.

BBC (2005, June 8). Chinese gamer sentenced to life. BBC News. Retrieved April 1, 2013, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/4072704.stm.

Björk, S. and Holopainen, J. (2004). Patterns in game design. Boston: Charles River Media.

Callois, R. ([1958] 1961). Man, play and games. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Castronova, E. (2001, December). Virtual worlds: a first-hand account of market and society on the cyberian frontier. CESifo Working Paper Series No. 618. Retrieved April 1, 2013, from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=294828.

Cohn, D. (2000). Distinction in fiction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Dixon, D. (2009). Nietzsche contra Caillois: beyond play and games. The philosophy of computer games conference, Oslo. Retrieved April 1, 2013, from www.hf.uio.no/ifikk/english/research/projects/thirdplace/Conferences/proceedings/Dixon%20Dan%202009%20-%20Nietzsche%20contra%20Caillois%20Beyond%20Play%20and%20Games.pdf

Fullerton, T. (2008). Documentary games: putting the player in the path of history. In Z. Whalen and L. Taylor (Eds.), Playing with the past: history and nostalgia in videogames (pp. 215–238). Nashville: Vanderbilt UP.

Huizinga, J. ([1938] 1955). Homo ludens: a study of the play element in culture. Boston: The Beacon Press.

Juul, J. (2005). Half-real. Video games between real rules and fictional worlds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Klabbers, J. (2003). The gaming landscape: a taxonomy for classifying games and simulations. In M. Copier and J. Raessens (Eds.), Level Up conference proceedings (pp. 54–67). Utrecht: Utrecht University. Retrieved April 1, 2013, from www.digra.org/dl/db/05163.55012.pdf.

Moulthrop, S. (1991). You say you want a revolution? Hypertext and the laws of media. Postmodern Culture, 1(3). Retrieved April 1, 2013, from http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/postmodern_culture/v001/1.3moulthrop.html.

Schiller, F. ([1795] 1957). Über naive und sentimentalische Dichtung. Oxford: Blackwell.

Suits, B. (1978). The grasshopper: games, life and utopia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Sutton-Smith, B. (1997). The ambiguity of play. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walton, K. L. (1990). Mimesis as make-believe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wittgenstein, L. ([1953] 2001). Philosophical investigations. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell.

Ziegfeld, R. (1989). Interactive fiction: a new literary genre? New Literary History, 20(2), 341–372.