Chapter 19. The Corporate iPhone

In its younger days, people thought of the iPhone as a personal device, meant for consumers and not for corporations. But somebody at Apple must have gotten sick of hearing, “Well, the iPhone is cool and all, but it’s no BlackBerry.” The iPhone now has the security and compatibility features your corporate technical overlords require. (And the BlackBerry—well...)

Even better, the iPhone can talk to Microsoft Exchange ActiveSync servers, staples of corporate computer departments that, among other things, keep smartphones wirelessly updated with the calendar, contacts, and email back at the office. (Yes, it sounds a lot like iCloud or the old MobileMe. Which is probably why Apple’s MobileMe slogan was “Exchange for the rest of us.”)

The Perks

This chapter is intended for you, the iPhone owner—not for the highly paid, well-trained, exceedingly friendly IT (information technology) managers at your company.

Your first task is to convince them that your iPhone is now secure and compatible enough to welcome into the company’s network. Here’s some information you can use:

Microsoft Exchange ActiveSync. Exchange ActiveSync is the technology that keeps smartphones wirelessly synced with the data on the mother ship’s computers. The iPhone works with Exchange ActiveSync, so it can remain in wireless contact with your company’s Exchange servers, exactly like BlackBerry and Windows Mobile phones do.

Your email, address book, and calendar appointments are now sent wirelessly to your iPhone so it’s always kept current—and they’re sent in a way that those evil rival firms can’t intercept. (It uses 128-bit encrypted SSL, if you must know.)

Note

That’s the same encryption used by Outlook Web Access (OWA), which lets employees check their email, calendar, and contacts from any web browser. In other words, if your IT administrators are willing to let you access your data using OWA, they should also be willing to let you access it with the iPhone.

Mass setup. These days, iPhones may wind up in corporations in two ways: They’re either handed out by the company, or you bring your own. (When employees use their own phones for work, they call it BYOD: “Bring your own device.”)

Most companies set up employee iPhones using mobile device management (MDM) software. That’s a program (for sale by lots of different security companies) that gives your administrators control over a huge range of corporate apps, settings, and restrictions: all Wi-Fi, network, password, email, and VPN settings; policies about what features and apps you can use, and so on; and the ability to remotely erase or lock your phone if it gets lost. Yet MDM programs don’t touch the stuff that you install on your own. If you leave the company, your old employer can delete its own stuff, while preserving your personal stuff.

Security. The iPhone can connect to wireless networks using the latest, super-secure connections (WPA Enterprise and WPA2 Enterprise), which are highly resistant to hacker attacks. And when you’re using virtual private networking, as described at the end of this chapter, you can use a very secure VPN protocol called IPsec. That’s what most companies use for secure, encrypted remote access to the corporate network. Juniper and Cisco VPN apps are available, too.

Speaking of security: Whenever your phone is locked, iOS automatically encrypts all email, email attachments, calendars, contacts, notes, reminders, and the data of any other apps that are written to take advantage of this feature.

iOS improvements. You can encrypt individual email messages to people in your company (and, with some effort, to people outside your company; see http://support.apple.com/kb/HT4979). When you’re setting up a meeting, you can see your coworkers’ schedules in the Calendar app. You can set up an automatic “Out of office” reply that’s in force until a certain date. (It’s in Settings→Mail. Tap your Exchange account’s name and scroll down to Automatic Reply.) Lots more control for your IT overlords, too.

And what’s in it for you? Complete synchronization of your email, address book, and calendar with what’s on your PC at work. Send an email from your iPhone; find it in the Sent folder of Outlook at the office. And so on.

You can also accept invitations to meetings on your iPhone that are sent your way by coworkers; if you accept, these meetings appear on your calendar automatically, just as on your PC. You can also search the company’s master address book, right from your iPhone.

The biggest perk for you, though, is just getting permission to use an iPhone as your company-issued phone.

Setup

Your company’s IT squad can set up things on their end by consulting Apple’s free setup guide: the infamous iOS Deployment Reference.

It’s filled with handy tips, like: “Data can be symmetrically encrypted using proven methods such as AES, RC4, or 3DES. iOS devices and current Intel Mac computers also provide hardware acceleration for AES encryption and Secure Hash Algorithm 1 (SHA1) hashing, thereby maximizing app performance.”

In any case, you (or they) can download the deployment guide from this site: www.apple.com/support/iphone/business.

Your IT pros might send you a link that downloads a profile—a preconfigured file that auto–sets up all your company’s security and login information. It will create the Exchange account for you (and might turn off a few iPhone features, like the ability to switch off the passcode requirement).

If, on the other hand, you’re supposed to set up your Exchange account yourself, then tap Settings→Mail→Add Account→Exchange. Fill in your work email address and password as they were provided to you by your company’s IT person.

And that’s it. Your iPhone will shortly bloom with the familiar sight of your office email stash, calendar appointments, and contacts.

Life on the Corporate Network

Once your iPhone is set up, you should be in wireless corporate heaven:

Email. Your corporate email account shows up among whatever other email accounts you’ve set up (Chapter 15). In fact, you can have multiple Exchange accounts on the same phone.

Not only is your email “pushed” to the phone (it arrives as it’s sent, without your having to explicitly check for messages), but it’s also synced with what you see on your computer at work. If you send, receive, delete, flag, or file any messages on your iPhone, you’ll find them sent, received, deleted, flagged, or filed on your computer at the office. And vice versa.

All the email niceties described in Chapter 15 are available to your corporate mail: opening attachments, rotating and zooming them, and so on. Your iPhone can even play back your office voicemail, presuming that your company has one of those unified messaging systems that send out WAV audio file versions of your messages via email.

Oh—and when you’re addressing an outgoing message, the iPhone’s autocomplete feature consults both your built-in iPhone address book and the corporate directory (on the Exchange server) simultaneously.

Tip

Your phone can warn you when you’re addressing an email to somebody outside your company (a security risk, and something that sometimes arises from autocomplete accidents).

To turn on this feature, open Settings→Mail. Scroll down; tap Mark Addresses. Type in your company’s email suffix (like yourcompany.com). From now on, whenever you address an outgoing message to someone outside yourcompany.com, it appears in red in the “To:” line to catch your eye.

Contacts. In the address book, you gain a new superpower: You can search your company’s master name directory right from the iPhone. That’s great when you need to track down, say, the art director in your Singapore branch.

To perform this search, open the Contacts app. Tap the Groups button in the upper-left corner. On the Groups screen, your company’s name appears; it may contain some group names of its own. But below these, a new entry appears that mere mortal iPhone owners never see. It might say something like Directory or Global Address Book. Tap it.

On the following screen, start typing the name of the person you’re looking up; the resulting matches appear as you type. (Or type the whole name and then tap Search.)

In the list of results, tap the name you want. That person’s Info screen appears so that you can tap to dial a number or compose a preaddressed email message. (You can’t send a text message to someone in the corporate phone book, however.)

Calendar. Your iPhone’s calendar is wirelessly kept in sync with the master calendar back at the office. If you’re on the road and your minions make changes to your schedule in Outlook, you’ll know about it; you’ll see the change on your iPhone’s calendar.

There are some other changes to your calendar, too, as you’ll find out in a moment.

Tip

Don’t forget that you can save battery power, syncing time, and mental clutter by limiting how much old calendar stuff gets synced to your iPhone. (How often do you really look back on your calendar to see what happened more than a month ago?) Calendar has the details.

Notes. If your company uses Exchange 2010 or later, then your notes are synced with Outlook on your Mac or PC, too.

Exchange + Your Stuff

The iPhone can display calendar and contact information from multiple sources at once—your Exchange calendar/address book and your own personal data, for example.

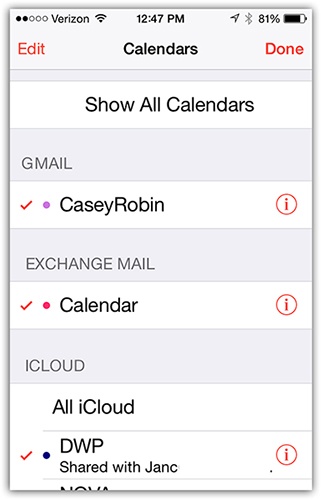

Here’s how it works: Open your iPhone calendar. Tap Calendars. Now you’re looking at all the accounts your phone knows about; you might find separate headings for iCloud, Yahoo, Gmail, and so on, each with calendar categories listed under it. And one of them is your Exchange account.

You can pull off a similar stunt in Contacts, Notes, and Reminders. Whenever you’re looking at your list of contacts, for example, you can tap the Groups button (top left of the screen). Here, once again, you can tap All Contacts to see a combined address book—or you can look over only your iCloud contacts, your Exchange contacts, your personal contacts, and so on. Or tap [group name] to view only the people in your tennis circle, book club, or whatever (if you’ve created groups); or [your Exchange account name] to search only the company listings.

Invitations

If you’ve spent much time in the world of Microsoft Outlook (that is, corporate America), then you already know about invitations. These are electronic invitations that coworkers send you directly from Outlook. When you get one of these invitations by email, you can click Accept, Decline, or Maybe.

If you click Accept, then the meeting gets dropped onto the proper date in your Outlook calendar, and your name gets added to the list of attendees maintained by the person who invited you. If you click Maybe, then the meeting is flagged that way, on both your calendar and the sender’s.

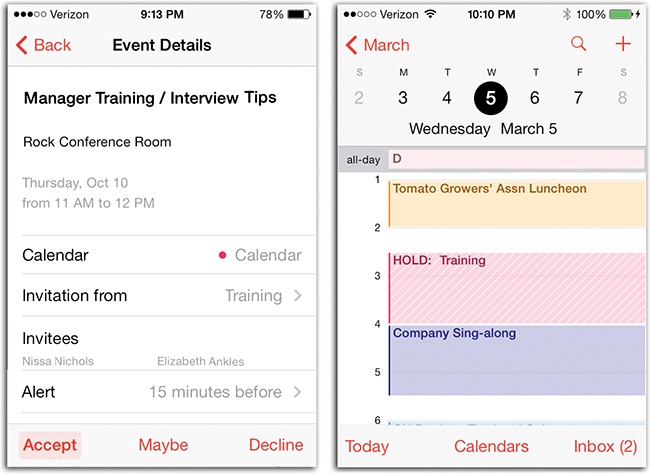

Exchange meeting invitations on the iPhone show up in four places, just to make sure you don’t miss them. You get a standard iPhone notification, a numbered “badge” on the Calendar app’s icon on the Home screen, an attachment to a message in your corporate email account, and a message in the Calendar app—tap Inbox at the lower-right corner. Tapping Inbox shows the Invitations list, which summarizes all invitations you’ve accepted, maybe’d, or not responded to yet. Tap one to see the details (below, left).

Tip

Invitations you haven’t dealt with also show up on the Calendar’s List view or Day view with dotted shading (below, right). That’s the iPhone’s clever way of showing you just how severely your workday will be ruined if you accept this meeting.

You can also generate invitations. When you’re filling out the Info form for a new appointment, you get a field called Invitees. Tap there to enter the email addresses of the people you’d like to invite.

Your invitation will show up in whatever calendar programs your invitees use, and they’ll never know you didn’t send it from some corporate copy of Microsoft Outlook.

A Word on Troubleshooting

If you’re having trouble with your Exchange syncing and can’t find any steps that work, ask your Exchange administrators to make sure that ActiveSync’s settings are correct on their end. You’ve heard the old saying that in 99 percent of computer troubleshooting, the problem lies between the keyboard and the chair? The other 1 percent of the time, it’s between the administrator’s keyboard and chair.

Virtual Private Networking (VPN)

The typical corporate network is guarded by a team of steely-eyed administrators for whom Job One is preventing access by unauthorized visitors. They perform this job primarily with the aid of a super-secure firewall that seals off the company’s network from the Internet.

So how can you tap into the network from the road? Only one solution is both secure and cheap: the virtual private network, or VPN. Running a VPN lets you create a super-secure “tunnel” from your iPhone, across the Internet, and straight into your corporate network. All data passing through this tunnel is heavily encrypted. To the Internet eavesdropper, it looks like so much undecipherable gobbledygook.

VPN is, however, a corporate tool, run by corporate nerds. Your company’s tech staff can tell you whether or not there’s a VPN server set up for you to use.

If there is one, then you’ll need to know what type of server it is. The iPhone can connect to VPN servers that speak PPTP (Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol) and L2TP/IPsec (Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol over the IP Security Protocol), both relatives of the PPP language spoken by modems. Most corporate VPN servers work with at least one of these protocols.

The iPhone can also connect to Cisco servers, which are among the most popular systems in corporate America, and, with a special app, Juniper’s Junos Pulse servers, too.

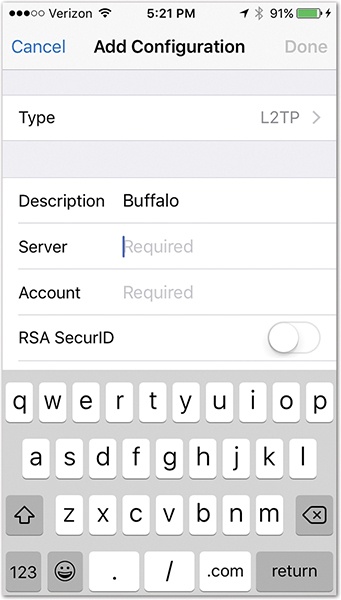

To set up your VPN connection, visit Settings→General→VPN.

Here you may see that your overlords have already set up some VPN connections; tap the one you want to use. You can also set one up yourself, by tapping Add VPN Configuration at the bottom.

Tap Type to specify which kind of server your company uses: IKEv2, IPsec, or L2TP (ask the network administrator). Fill in the Server address, the account name and password, and whatever else your system administrators tell you to fill in here.

Once everything is in place, the iPhone can connect to the corporate network and fetch your corporate mail. You don’t have to do anything special on your end; everything works just as described in this chapter.

Note

Some networks require that you type the currently displayed password on an RSA SecurID token, which your administrator will provide. This James Bondish thing looks like either a credit card or a USB drive. It displays a password that changes every few seconds, making it rather difficult for hackers to learn “the” password.

VPN on Demand

If you like to access your corporate email or internal website a few times a day, having to enter your name-and-password credentials over and over again can get old fast. Fortunately, iOS offers a huge timesaving assist with VPN on Demand.

That is, you just open up Safari and tap the corporate bookmark; the iPhone creates the VPN channel automatically, behind the scenes, and connects.

There’s nothing you have to do, or even anything you can do, to make this feature work; your company’s network nerds have to turn it on at their end.

They’ll create a configuration profile that you’ll install on your iPhone. It includes the VPN server settings, an electronic security certificate, and a list of domains and URLs that will automatically turn on the iPhone’s VPN feature.

When your iPhone goes to sleep, it terminates the VPN connection, both for security purposes and to save battery power.

Note

Clearly, eliminating the VPN sign-in process also weakens the security the VPN was invented for in the first place. Therefore, you’d be well-advised—and probably required by your IT team—to use the iPhone’s password or fingerprint feature, so some evil corporate spy (or teenage thug) can’t just steal your iPhone and start snooping through the corporate servers.