22Chapter 3

Common Clinical Concerns

Although every child or adolescent is unique, a handful of common concerns account for most of the reasons young people come to clinical attention. You learn to recognize these patterns during training. You see hundreds of children and adolescents, discuss them with clinical supervisors, and develop a subconscious ability to quickly recognize the ways a particular child resembles common concerning patterns. For instance, you may quickly recognize a child’s presentation pattern as typical of an uncomplicated adjustment to a new school rather than an episode of major depression. These subconscious patterns are a tremendous benefit to a practitioner because they help her improve her clinical efficiency.

However, relying on experience to guide your current practice causes at least two problems.

First, even seasoned practitioners make mistakes. We assume that an adolescent has an ordinary case of unhappiness, so we neglect to consider whether her social isolation is the result of abuse or psychosis. We assume that a child’s inability to play well with others represents a neurodevelopmental disorder, so we neglect to ask about cultural expectations for interactive play in a family. Even an experienced practitioner needs to remain curious about a particular patient and vigilant about the eventuality of making mistakes.

Second, most young people are evaluated and treated for mental illness by primary care practitioners with limited mental health training. These practitioners often have remarkable stores of clinical experience in caring for children and adolescents, but their mental health training is often limited to a few afternoons, a long-ago clinical rotation, or an occasional lecture. A practitioner whose training is not specialized for mental health can benefit from referencing prudent aids to decision making.

The following sections, and their accompanying tables, are prudent guides to common clinical concerns. Each table identifies a common clinical concern, provides diagnostic categories 23to which these concerns can be mapped, and suggests questions to guide clinical inquiry. We designed most questions to be asked of a young person. When a question is designed to be asked of a caregiver, we label it “for caregiver.”

Poor Academic Performance

To succeed in a work environment, a person needs the ability to succeed, the desire to succeed, and an environment that enables success. Major life distractions or impairing illnesses can unfortunately derail a person who would have otherwise found success. Although that simple description can be used to describe just about any adult workplace, the exact same points are true about children in school. School is where children and adolescents go to work.

When you see a child who is struggling to succeed in school, it is useful to think very broadly about what might be getting in her way (Table 3–1). Just like an adult who is having workplace difficulties, a young person may have problems with 1) ability, 2) desire or effort, 3) work environment, 4) life distraction, or 5) an impairing mental health disorder or illness.

1. Ability challenges we consider right away to ensure we do not miss them. The most basic ability is our senses. Hearing and vision screens are easy to perform, and when needed, an intervention such as a hearing aid or a new pair of glasses can make a profound difference. Motor impairments, such as the physical ability to write or enunciate clearly, also can be managed effectively through physical, occupational, or speech therapy.

Intellectual disabilities, of course, influence school success. You can determine whether a young child has fallen behind on developmental milestones by comparing her traits with a list of normal range expectations. Caregiver-completed developmental rating scale measures such as the Ages & Stages Questionnaires (ASQ) will aid this task, or you can simply ask a caregiver if she has had any concerns about the child’s speech, comprehension, or physical ability development. We would suspect an intellectual disability when the child has multiple areas of delay. IQ test scores provide helpful data, but impairments in adaptive life functioning also must be present to diagnose an intellectual disability. Early intervention services or a local school district’s special education program should be engaged as early as possible to improve outcomes when global developmental delay or an intellectual disability is suspected.

24TABLE 3–1. Poor academic performance

Diagnostic category |

Suggested screening questions |

First consider |

|

Abuse |

“Has anything or anyone made you feel uncomfortable or unsafe?” (for caregiver) “Has anything happened to your child that really shouldn’t have happened?” |

Bullying |

“Have other kids been teasing you or making you feel afraid?” |

Sensory impairment |

“Have you ever noticed any trouble with hearing or vision?” |

Common diagnostic possibilities |

|

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

(for caregiver) “Even when she wants to learn, is your child too inattentive or hyperactive to succeed?” |

Intellectual disability (intellectual development al disorder) |

(for caregiver) “Have there always been problems with learning? Were there early milestone delays such as speech delays?” |

Specific learning disorder |

“Are any specific subjects or activities such as reading particularly difficult?” |

Mood or anxiety disorder |

(for caregiver) “Did poor school performance come after an anxious or depressive change?” |

Oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder |

(for caregiver) “Is your child simply refusing to do schoolwork?” |

Substance use disorder |

“Have you been using drugs or alcohol?” |

25Specific learning disabilities are often detected much later than a general intellectual disability because they may not become apparent until school demands increase. The three overall categories of specific learning disabilities are reading, writing, and computation. The hallmark of a specific learning disability is that the child has an area of much poorer school performance than expected on the basis of the child’s overall intellect and effort.

2. Desire or effort in school is about the motivation to achieve. A person with a low to average intellect but a strong motivation to achieve can have greater school success than someone with high intellect but low motivation to achieve. There is no quick fix for motivation problems. For young children, motivation in school starts with healthy home relationships and regularly experienced positive parent-child time, which foster a desire to meet adult expectations. Clear and reasonable family expectations for the child’s school achievement are also necessary. For older children, this desire ideally evolves into working hard in school because they want to please themselves.

3. Work environment affects performance because not every school and not every classroom will suit every child. For instance, an easily distracted child will not do well in a loud and overcrowded classroom, and a child with a specific writing disability will not do well in a class that requires large volumes of daily written work completion. Asking about the class environment and the child’s home workspace may identify these issues.

4. Life distractions prevent success by taking a child’s mind off his or her schoolwork. Abuse, neglect, and bullying are the most important distractions for us to catch right away so that child protective services or school officials can intervene. Children may experience a decline in school performance because of family stressors such as parental separation or divorce or from struggling with peer relationships. It is useful to ask, “When you try to do your schoolwork but get distracted, what’s on your mind?”

265. Impairing mental health disorders or illnesses that are described in DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013) can create school problems. For instance, major depressive disorder, persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), social anxiety disorder (social phobia), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder, substance use disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) all will reduce a child’s school performance. Chronic medical diseases, especially those that involve experiencing daily pain, also will reduce the ability to focus on school.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the main mental disorder that gets considered in terms of a high overall incidence (>5%) and common family requests for treatment. We would look for ADHD if attention and/or hyperactivity-related schooling difficulties can be traced back to the early elementary school years and these difficulties are not readily attributed to any of the above causes. Sudden-onset attention problems are thus unlikely to be caused by ADHD. Another key trait to look for is whether ADHD-like symptoms are present in multiple settings (such as both in school and at home). The good news is that by correctly identifying an impairing illness such as ADHD, you have an opportunity to treat and resolve the schooling problem.

Developmental Delay

A person’s development from infancy to adulthood is amazing in its breadth and complexity. Because not every person develops at the same pace or in the same order of skill acquisition, detecting a significant developmental impairment may be challenging (Table 3–2). For instance, a child may learn to walk without ever crawling or may appear speech delayed at 18 months but speech advanced at 2 years. Fewer than half of the children with significant developmental delays are identified before starting school, which delays entry into treatment. Therefore, anything practitioners can do to help caregivers detect these problems can alter the trajectory of a child’s life. A key function of health maintenance care in the first 5 years of life is to detect developmental impairments that would benefit from an intervention. Any parental concerns expressed about a child’s speech, learning, sociability, or physical skills should open the proverbial door for further examination.

27TABLE 3–2. Developmental delay

Diagnostic category |

Suggested screening questions for caregiver |

First consider |

|

Neurodegenerative conditions |

“Has your child lost any previously acquired skills or abilities?” |

Sensory impairment |

“Have you ever noticed any trouble with your child’s hearing or vision?” |

Common diagnostic possibilities |

|

Autism spectrum disorder |

“Does your child smile in response to your smile? Did your child respond to her own name before age 1? Does your child have restricted interests or behaviors?” |

Communication disorder |

“Does your child have problems with stuttering or with understanding words?” |

Fragile X syndrome |

“Does your child have siblings or relatives on the mother’s side of the family with intellectual impairment?” |

Intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder) or global developmental delay |

“Was your child slow to develop speech and physical skills? Does your child have a harder time learning new things than other children?” |

Neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure |

“What can you tell me about alcohol use during pregnancy? Has your child had difficulty regulating his or her mood or impulses?” |

28Development can be broken down into three broad categories: cognitive, motor, and social-emotional. Cognitive development refers to what most people think of as intelligence. Some measurable areas of cognition include problem solving, language, memory, information processing, and attention. Motor development refers to the acquisition of gross motor (e.g., run, throw) and fine motor (e.g., pincer grasp, drawing) physical motion skills. Social-emotional development refers to the acquisition of the ability to interact with others and manage the emotions of social interactions.

Because there is a very wide range of what can be considered “normal” development, we look for developmental markers that are far enough outside the norm to justify referral for developmental assessments or interventions. When parents express that they already have concerns about a specific area of their child’s development, we will likely find a need for a developmental assessment referral. Speech therapists can help with suspected communication delays, physical therapists can help with suspected motor skill delays, and special education–sponsored preschools can help with suspected socialization and general learning skill delays. All children with significant developmental delays should be referred to early intervention services.

Detecting autism spectrum disorder before a child reaches age 3 years is aided by recognizing certain red flags in social-emotional development. These include not smiling in response to being smiled at, not making eye contact, not sharing attention with others, not responding to her own name by age 1 year, poor social interest, and a lack of interest in other children. Socially focused interventions that foster communication as early as possible are a cornerstone of autism care.

Every child with developmental impairment should be screened for hearing or vision impairments because sensory impairments can worsen or even cause developmental impairments. Another reason for early sensory assessments is that hearing and vision impairments can be relatively easy to treat.

A developmental impairment rarely worsens over time, so when we find any loss of previously acquired skills, we broaden our search for an etiology to include medical causes. For example, hypothyroidism, phenylketonuria, and recurrent seizures are some of the many medical causes of regressing development.

29We recommend considering genetic testing if the clinical pattern might fit a genetic disorder. For instance, fragile X testing is particularly pertinent if other family members have intellectual disability. If no specific genetic disorder is suspected, the yield of genetic testing will be reduced. Developmental disorder laboratory tests for fragile X and chromosome micro-array should be ordered only after providing pretest counseling to families. Family risks from genetic testing include finding an unknown significance mutation that creates more anxiety than answers or learning something the family did not wish to learn, such as misattributed paternity or a pessimistic prognosis that lowers current quality of life.

Diagnosing a child with neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure, included in Section III of DSM-5, can be a challenge to your therapeutic alliance with caregivers because it inherently assigns blame for some of a child’s problems on her mother’s behaviors during pregnancy. Characteristic facial features (thin upper lip, smooth philtrum, short palpebral fissure length) might be present, but their absence does not rule out the diagnosis. Because these children do have a unique prognosis, it is worth exploring this possibility in a blame-free fashion.

In Chapter 12, “Developmental Milestones,” we further review developmental milestones and discuss developmental red flags, signs that need further evaluation, ideally through specialized developmental assessments.

Disruptive or Aggressive Behavior

When we see a young person who is aggressive or disruptive, we receive that behavior as a form of communication. A child who is unable to effectively communicate verbally may use behaviors instead, such as lashing out at a peer who has just taken her toy. Hunger, pain, sadness, fear, and frustration are just a few examples of distress that may turn into tantrums, disruptive behavior, or aggression. For instance, if you can identify that hunger leads to a tantrum in a nonverbal child, the child can be coached to point at a picture of food to communicate hunger and get something to eat (this is known as a picture exchange system).

A functional analysis of behavior is an overall approach that helps with most aggression problems in childhood. In a functional analysis, you identify the character, timing, frequency, 30and duration of at least a few incidents of disruptive, aggressive behavior in great detail. Predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating influences on behavior can be elicited by asking a series of questions such as “Tell me about the last time this happened. What was happening right before? How had that day been going overall? What did you do while the behavior was happening? What happened right afterward?”

What you often discover from the unedited details of two or three incidents is that the aggressive and disruptive behaviors begin to make a lot more sense. Examples include tantrums inadvertently being rewarded with treats because caregivers want the child to stop in the moment or aggression that allows a child to successfully escape aversive situations.

Different DSM-5 disorders may be suggested by particular circumstances of the child’s disruptive behaviors (Table 3–3). Children with PTSD may become disruptive when situations remind them of past negative events. Children with a learning disability may be disruptive when struggling at school or working on homework. A child with ADHD may have nearly continuous, disruptive hyperactivity that is not situational or vindictive. A child with social anxiety disorder (social phobia) or autism spectrum disorder may show disruptive behavior when pushed to engage in social situations. A child who has been bullied at school may suddenly develop disruptive, lashing-out behavior or become resistant to going to school. In summary, identifying the overall pattern and context of behaviors is key to the diagnostic process.

It is relatively easy to identify ODD, a diagnosis that describes pervasively negativistic and defiant behavior toward authority figures in a developmentally inappropriate fashion (i.e., not just the “terrible twos”) that lasts for more than 6 months. The real challenge is knowing what to do about it.

ODD has a complex, multifactorial etiology. In simple terms, ODD represents a mismatch in fit between a child’s inherent traits or temperament and how her caregivers and authority figures respond to them. Communicating to caregivers that they share responsibility with their child for the negative behavior patterns in ODD without this being perceived as blaming them for the problem is a tricky balance. One way to do so is to characterize the child’s personality or biology as requiring higher-than-usual parenting demands, so more highly skilled parenting strategies are needed to respond to ODD. Empathy for the challenge parents face goes a long way here.

31TABLE 3–3. Disruptive or aggressive behavior

Diagnostic category |

Suggested screening questions |

First consider |

|

Abuse |

“Has anything or anyone made you feel uncomfortable or unsafe?” (for caregiver) “Has anything happened to your child that really shouldn’t have happened?” |

Bullying |

“Have other kids been teasing you or making you feel afraid?” |

Safety |

“Have you been thinking about or planning to hurt anyone?” |

Common diagnostic possibilities |

|

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

(for caregiver) “Does your child consistently have trouble paying attention, or is she hyperactive or disruptive?” |

Communication disorder |

(for caregiver) “Is your child aggressive when she has needs she cannot communicate?” |

Conduct disorder |

(for caregiver) “Has your child been committing serious violations of rules and the rights of others for more than a year?” |

Oppositional defiant disorder |

(for caregiver) “Has your child been unusually defiant and oppositional for more than 6 months?” |

Posttraumatic stress disorder |

(for caregiver) “Does your child’s disruptive behavior primarily occur after reminders or memories of past trauma?” |

32Conduct disorder is a similar, but more concerning, version of defiant, aggressive behavior that has a greater risk of continuing into adulthood. Conduct disorder should be suspected when a child is committing serious violations of the rights of others, such as stealing, initiating fights, using a weapon to threaten others, destroying property, or running away from home.

Successful management of ODD and conduct disorder requires motivating authority figures in a child’s environment to make changes in how they interact with the child. The traditional one-on-one psychotherapy approach rarely will be sufficient. Behavior management training is the best overall treatment strategy for both ODD and conduct disorder. There are many types of behavior management training, but they all share a focus on coaching parents and caregivers to set better limits and expectations for the child and a focus on the child and parents regularly spending positive times together, thus providing opportunities for the child to experience praise. Historically, this approach was referred to as parent training, but we think that term should be discarded for unnecessarily assigning fault to the parents, which reduces the therapeutic alliance and motivation for change. The more severe the symptoms, the more community inclusive the behavior management approach should be, such as how multisystemic therapy also engages nonparental authority figures in the community for patients with conduct disorder.

Medications are generally not the preferred treatment for disruptive or aggressive behavior. However, if the child has a specific DSM-5 diagnosis that is known to be medication responsive, such as ADHD or major depressive disorder, then medication treatment typically will improve disruptive or aggressive behavior. No medications are indicated for the treatment of ODD or conduct disorder, whose best treatment is via coaching and supporting the child’s authority figures. If a disruptive or aggressive problem is considered to be highly impairing and other appropriate interventions have been tried and have failed, then a nonspecific medication to diminish maladaptive or impulsive aggression may be considered. If this is done, we would recommend a clonidine or guanfacine trial first because if they are helpful, their use presents few long-term medical risks. Second-generation antipsychotics such as risperidone may be effective in reducing aggression, but antipsychotics have more significant adverse effects and should be reserved for the most severe scenarios (Loy et al. 2012).

33Withdrawn or Sad Mood

When a young person presents as withdrawn or sad (Table 3–4), we always assess for the presence of a major depressive episode. Two or more weeks of depressed or irritable mood, along with multiple neurovegetative symptoms (decreased energy, concentration, interest, or physical activity; thoughts of self-harm; changes in appetite or sleep; and feelings of guilt or worthlessness), would suggest a major depressive episode. In contrast, persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia) is essentially a low-grade depression that has been present for more than a year in a child, without relief for more than 2 months during that time. If the sad mood was triggered by a stressful event within the past 3 months and neither major depression nor dysthymia is diagnosable, an adjustment disorder with depressed mood may be present.

Regardless of whether a withdrawn or sad child has an active mood disorder, routinely asking about self-harm risks is important. Adolescents may see even a single disappointment—such as a relationship breakup—as so catastrophic that they feel suicidal or begin to hurt themselves. This means that as practitioners we must ask about suicidal thoughts and self-harm urges even if we believe that a young person is experiencing only a time-limited adjustment disorder. With practice, we find that asking about suicidality and self-harm comes as naturally as asking any other question. It helps to keep in mind that asking about suicidal thoughts does not create a risk of self-harm. Instead, it reduces risks by showing you care.

Although medically induced depression is uncommon in a young person, all practitioners must be alert to the possibility. For instance, testing for hypothyroidism is reasonable if a patient experienced physical symptoms such as fatigue before mood changes developed. Because anemia is a common problem in young people, a complete blood count should be considered to assess its presence in a patient who is fatigued. Iatrogenic origins of depression should be considered as well, such as when a child starting β-blockers or isotretinoin subsequently experiences dysphoria.

Recurrent substance abuse can cause an adolescent to appear depressed. Because we find that adolescents typically assert that they see their substance use as helping their mood, establishing a timeline of what came first may help you convince your patient to discontinue the substance at least temporarily and find out how she feels after a few weeks of being substance free.

TABLE 3–4. Withdrawn or sad mood

Diagnostic category |

Suggested screening questions |

First consider |

|

Abuse |

“Has anything or anyone made you feel uncomfortable or unsafe?” (for caregiver) “Has anything happened to your child that really shouldn’t have happened?” |

Bullying |

“Have other kids been teasing you or making you feel afraid?” |

Medical conditions (anemia, hypothyroidism) |

“Did all of your symptoms seem to start with fatigue?” |

Self-harm |

“Have you been thinking about hurting yourself? Have you ever hurt yourself or attempted suicide? Do you have any plans to hurt yourself?” |

Common diagnostic possibilities |

|

Adjustment disorder with depressed mood |

“Did your sad or down mood start right after a stressful event in the past few months?” |

Bipolar disorder |

“Has there ever been a period of multiple days in a row when you were the opposite of depressed, with very high energy and little need for sleep? If so, can you tell me more about that time?” |

Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia) |

“Have you been sad or gloomy most days of the week for more than a year?” |

Major depressive disorder |

“Have you felt really down, depressed, or uninterested in things you used to enjoy for more than 2 weeks?” |

Substance use disorder |

“Have you been using drugs or alcohol?” |

34Bipolar disorder is relatively uncommon in children but should be considered. To detect the possibility of bipolar depression, we ask caregivers if the child has ever had a history of discrete mood elevation and energy increase of multiple days’ duration with accompanying manic symptoms (e.g., racing thoughts or speech, unusual risk taking, and decreased need for sleep). Notably, the presence of an irritable mood is not a reliable indicator of bipolar disorder in children. If you suspect that a young person with a withdrawn or sad mood has bipolar disorder, monotherapy with antidepressants should be avoided because of their risk for inducing a manic episode.

Every child with a moderate to severe depressive disorder should be referred for an evidence-based psychotherapy, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or interpersonal therapy. Because the level of family motivation to use psychotherapy is a common problem, we often address this up front by informing families that psychotherapy is the most effective strategy available to reduce the risks of suicidality. Caregivers of a young person can also take the safety steps of restricting impulsive access to firearms and dangerous pills and maintaining increased awareness and monitoring. In the presence of active suicide plans or the inability to maintain immediate safety, practitioners should consider admission to a crisis stabilization unit, day treatment program, or psychiatric inpatient treatment. Families also can help the child by promoting “behavioral activation” treatment for depression at home through scheduling desirable exercise and social activities.

The current view on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use for depression is that some young patients might experience an increase in suicidal thoughts during the first few months of SSRI use, but most do not, and overall, the benefits of use outweigh potential risks for a moderate to severe depression. A prudent practitioner will warn patients about the possible risk, stay connected with patients and the patient’s caregivers after the initial prescription to inquire specifically about increased irritability or suicidal thoughts at least twice in the first month of use, and strongly consider stopping the medication should increased irritability or suicidality occur (Bridge et al. 2007).

35Because of its large research evidence base indicating benefits in young people, fluoxetine is widely considered the first-line choice for adolescent major depressive disorder. Second-line SSRI choices based on the evidence include sertraline and escitalopram or citalopram. Usual adolescent depression starting doses are 10 mg for fluoxetine, 25–50 mg for sertraline, 10 mg for citalopram, and 5 mg for escitalopram; about half of these amounts are used in preadolescents. Doses should be increased after 4–6 weeks if the medications are well tolerated but have insufficient benefits. SSRIs are most effective when used in combination with psychotherapy, which is another reason to promote the family’s engagement with psychotherapy. Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia) would be treated with the same medications but is notably slower to respond (McVoy and Findling 2013).

Irritable or Labile Mood

A young person may experience an irritable or labile mood for several reasons (Table 3–5). Several mental disorders— bipolar disorders, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, PTSD, and ODD—should be considered because irritability can be a symptom of a mental disorder. It also can be a symptom of substance abuse, a reaction to challenging life situations or maltreatment, or a normal variation in mood. When irritability is the primary complaint, we counsel a broad search for clues as to “why.”

Unfortunately, there has been a major misdiagnosis problem during the past two decades because chronically irritable, labile moods in children were being interpreted as being pathognomonic of a childhood bipolar disorder. This was usually incorrect, in that few (if any) chronically irritable children were later found to have bipolar disorder as young adults (Birmaher et al. 2014). Unless a child has multiday duration manic symptoms occurring during a discrete episode that represents a break from baseline functioning, we counsel against diagnosing bipolar disorder in children and adolescents.

In part because of this perceived need to have a diagnosis that better characterizes children with life dysfunction because of chronically irritable moods, a new diagnosis was created. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder is a new DSM-5 diagnosis for children who have more than a year of significant daily dysphoric mood symptoms and temper outbursts three or more times a week that are not better explained by other conditions. However, this is a new diagnosis, so we know very little about prognosis or best treatments (Roy et al. 2014). Practically speaking, we believe disruptive mood dysregulation disorder could be considered as a variant of ODD in which mood symptoms predominate.

36TABLE 3–5. Irritable or labile mood

Diagnostic category |

Suggested screening questions |

First consider |

|

Abuse |

“Has anything or anyone made you feel uncomfortable or unsafe?” (for caregiver) “Has anything happened to your child that really shouldn’t have happened?” |

Substance abuse |

“Have you been using drugs or alcohol?” |

Suicidality |

“Have you had thoughts about hurting yourself?” |

Common diagnostic possibilities |

|

Bipolar disorder |

“Has there ever been a period of multiple days in a row when you were the opposite of depressed, with super high energy and little need for sleep? If so, can you tell me more about that time?” |

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder |

(for caregiver) “Has your child had severe and persistent irritability along with frequent temper outbursts?” |

Major depressive disorder |

“Have you felt really down, depressed, or uninterested in things you used to enjoy for more than 2 weeks?” |

Oppositional defiant disorder |

(for caregiver) “Has your child been unusually defiant and oppositional for more than 6 months?” |

Posttraumatic stress disorder |

(for caregiver) “Does the irritability or moodiness worsen after reminders or memories of past trauma?” |

37Even if a young person’s irritability cannot ultimately be traced to a specific DSM-5 diagnosis with a known treatment, a generalized approach to managing irritable moods can still be helpful. We recommend enhancing family supports and providing behavior management training as appropriate for most types of irritable mood care. Creating calm, consistent, and caring limits and expectations within the household will typically improve behavior problems and irritability from a wide variety of causes.

Families with significant internal conflict can benefit from family therapy or from caregivers seeking their own individual supports. You may be able to motivate parents who report feeling exasperated with a child by using a “put your own mask on first” analogy, as with airline travel. An unnurtured parent who receives individual supports or professional help may greatly improve interactions with her child. For those children who are found to lack positive experiences with their caregivers, creating opportunities for praise and positive attention is a key to treatment success.

One-on-one counseling therapy is indicated for all mood disorders and anxiety-related conditions (including PTSD) with an irritability component. Medication is never indicated for irritable mood without a specific diagnosis.

Anxious or Avoidant Behavior

When a child is struggling with being worried or anxious, we first check if something in a child’s world is directly causing this feeling. Anxiety from being bullied, from experiencing a major traumatic event, or from living in an abusive household should appropriately generate self-protective avoidance behaviors. Only after we know that no realistic threat to the child exists and have determined that the child’s anxiety causes significant life dysfunction do we consider an anxiety disorder diagnosis (Table 3–6).

38TABLE 3–6. Anxious or avoidant behavior

Diagnostic category |

Suggested screening questions |

First consider |

|

Abuse |

“Has anything or anyone made you feel uncomfortable or unsafe?” (for caregiver) “Has anything happened to your child that really shouldn’t have happened?” |

Bullying |

“Have other kids been teasing you or making you feel afraid?” |

Trauma |

“Have you been hurt recently or been in any accidents?” |

Self-harm |

“When you feel overwhelmed, do you think about hurting yourself?” |

Common diagnostic possibilities |

|

Generalized anxiety disorder |

“Do you feel tense, restless, or worried most of the time? Do these worries affect your sleep or performance at school?” |

Obsessive-compulsive disorder |

“Do you frequently have unwanted thoughts, images, or urges in your mind? Do you check or clean things to avoid those unwanted thoughts?” |

Panic disorder |

“Do you get sudden surges of fear that make your body feel shaky or your heart race? Do you change what you do in order to avoid having a panic experience?” |

Posttraumatic stress disorder |

“Do you startle easily or have frequent nightmares? Do you avoid reminders of traumatic events in your past?” (for caregiver) “Does the irritability or moodiness worsen after reminders or memories of past trauma?” |

Separation anxiety disorder |

“Is it hard to leave your house or hard to leave your mom or dad because of worries?” |

Specific phobia |

“Is there something in particular or a situation that makes you immediately afraid?” |

39Children have worries during the course of their normal development, such as fears of strangers, separation, injury, or failure. Learning how to cope with anxious feelings by facing them directly is an important developmental task that, once mastered, enables future achievements. Parental anxiety may interfere with this process if it reinforces a child’s fears or encourages avoidance behavior. For instance, inadvertent parental reinforcement of normal separation anxiety may turn this problem into a disorder unless the parent is taught more helpful strategies.

Children who feel anxious often struggle to find words to express how they feel. A child reporting stomachaches, nausea, chest pain, fatigue, or headaches may be functionally disclosing that she feels anxious, but through a biological mechanism such as autonomic nerves altering intestinal motility or arterial smooth muscle tone. In fact, the chief complaint of children and adolescents seeking mental health treatment in primary care settings often will be a physical ailment. When listening alertly for any meaning behind a physical ailment, practitioners should think about timing. Severe stomach cramps before attending school or headaches before performing in a sporting event will help identify anxiety disorders.

Common anxiety disorders for children include GAD, panic disorder, specific phobia, and separation anxiety disorder. These conditions could appear in a developmental trajectory, such as separation anxiety disorder during the elementary school years being replaced by specific phobias in middle school and then a GAD in the adolescent years. For some children, their anxiety trait persists, but the expressed form of that anxiety varies over time. Isolated panic attacks are a short-term anxiety symptom that may appear with other disorders such as depression. Panic disorder is different, involving a disabling fear of experiencing future panic episodes.

Anxiety disorders commonly run in families; thus, when a child is given an anxiety disorder diagnosis, either or both parents likely have struggled with anxiety disorders themselves. This familial tendency can occur through shared genetic traits, through children absorbing the anxious sentiments a parent generates within the household, or both. In some situations, the most effective way to help an anxious child is to help her parent to more effectively manage her own anxiety and thus create a more stable and supportive home environment for the child.

40Strategies shown to be effective for anxiety treatment in children include different forms of psychotherapy in which exposure to feared thoughts or ideas is their most common element (Chorpita and Daleiden 2009). Repeated exposure to feared situations or memories that do not have any negative consequences, through repetition and reframing, will help the child’s mind to unlearn that fear. However, if that fear is still a “real” one, such as a traumatized child at risk for future abuse, then psychotherapy alone will not be as beneficial until the child’s safety is secured. CBT is the most commonly available modality for anxiety treatment that uses exposure.

Parents also must challenge or restrict the avoidance behaviors in their child because avoidance of a feared situation leads to a temporary relief of anxiety that over time reinforces the fear and worsens the severity of the anxiety. For instance, a fear of attending school becomes stronger if the child is allowed to repeatedly skip school. SSRIs, including sertraline and fluoxetine, have been shown in multiple studies to be effective in treating different forms of childhood anxiety disorders and are most effective when used in combination with psychotherapy (Mohatt et al. 2014).

OCD and PTSD are anxiety-related diagnoses that are now listed in their own sections of DSM-5: “Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders” (which includes hoarding disorder and trichotillomania) and “Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders” (which includes acute stress and adjustment disorders). OCD responds very well to the same first-line therapies as used for other anxiety disorders: CBT and SSRIs. PTSD has been found to respond well to exposure-based therapies such as trauma-focused CBT, but its response to medications in children is not so well established.

Recurrent and Excessive Physical Complaints

Primary care practitioners know that recurrent headaches, chest pain, nausea, and fatigue are the presenting concern in about 10% of all office visits by adolescents, and recurrent abdominal pain alone is the presenting concern for about 5% of all pediatric office visits (Silber 2011). Although these somatic complaints may have many etiologies, the most common etiologies are psychiatric. Knowing this, whenever we hear a psychosomatic complaint, we consider whether anxiety disorders, 41depressive disorders, or adjustment disorders are the cause. Treatments for anxiety and depression are both effective and straightforward. The treatments for somatic disorders (somatic symptom disorder, factitious disorder, conversion disorder) are more challenging, so we consider them after ruling out anxiety and depressive disorders (Table 3–7).

We do not, however, favor considering somatic disorders only after excluding all possible causes for somatic complaints. Contemporary medicine overvalues biological explanations for somatic symptoms and usually leaves other explanations, including psychiatric etiologies, as diagnoses of exclusion. The unfortunate effects of a medical-before-psychiatric approach are that

• Mental illness may go unrecognized.

• Patients and parents may react poorly to hearing an “it is all in your head” explanation after multiple investigations and appointments.

• Families may try to prove that symptoms are “real” and insist on inappropriate tests or procedures.

• Acceptance of psychiatric care or forms of appropriate functional assistance may be decreased.

To counteract these pitfalls, we recommend describing psychiatric etiologies to families when presenting your initial somatic symptom differential diagnosis and then openly discussing them throughout. You can do this by describing what you think are the most likely psychobiological pathways for somatic symptoms. For instance, you can explain how stress affects the autonomic nervous system, which can lower gastric pH and alter intestinal motility (for nausea and abdominal pain) or can alter blood vessel smooth muscle tone (for headaches). By offering a biological account for physical symptoms of a mental illness, you will help patients and their caregivers more readily accept psychiatric interventions such as CBT and relaxation therapy because you have taught them that psychiatric intervention can modify autonomic nervous system functioning.

Children with somatic symptom disorders usually lack awareness that stress or anxiety is linked to their physical experiences or may lack an ability to adequately use words to describe their emotional states (referred to as alexithymia). The classic childhood pattern is that somatic symptoms increase before stressful experiences, such as attending school, visiting someone else’s home, or performing publicly, whereas the somatic symptoms decrease if stressful situations are avoided. Specifically experienced symptoms may change over time, in that a child with recurrent abdominal pain early in life may develop recurrent headaches and fatigue as a teenager.

42TABLE 3–7. Recurrent and excessive physical complaints

Diagnostic category |

Suggested screening questions |

First consider |

|

Abuse or maltreatment |

“Has anything or anyone made you feel uncomfortable or unsafe?” (for caregiver) “Has anything happened to your child that really shouldn’t have happened?” |

Adjustment disorder |

“Was there something stressful in the past 3 months that happened right before these symptoms appeared?” |

Anxiety disorders |

(for caregiver) “Does your child have a lot of worries that cause distress?” |

Depressive disorders |

(for caregiver) “Has your child’s mood been unusually down or low for more than a couple of weeks?” |

Other diagnostic possibilities |

|

Conversion disorder |

For practitioner: consider when you identify a loss of motor or sensory function that is inconsistent with recognized disorders. |

Factitious disorder imposed on self |

(for caregiver—asked away from the child) “Do you suspect your child may be intentionally exaggerating symptoms?” |

Factitious disorder imposed on another |

For practitioner: consider when parent has pattern of reporting symptoms in her child inconsistent with recognized disorders. |

Panic attacks |

“Do you experience sudden surges of fear that make your body feel shaky or your heart race?” |

Somatic symptom disorder |

(for caregiver) “Does your child have recurrent physical symptoms that disrupt his or her daily life? Does your child have an excessive focus on his or her physical symptoms?” |

43In the case of a conversion disorder with prominent unusual motor problems (such as paralysis of only one shoulder) or sensory problems (such as a loss of all feeling in the legs with normal reflexes), we similarly find it important to help the child exit her presentation without accusing her of having biologically “false” symptoms. For instance, you can explain to a patient that your examination identified no major medical difficulties but that in your experience other young people with similar symptoms experienced a fairly rapid resolution. A face-saving explanation such as “I believe that in a short time your nerves will simply reset themselves, like how the seasons change” may be particularly helpful. Successfully responding to conversion symptoms relies as much on the art of medicine as on the science of medicine.

A young person also may intentionally falsify symptoms to malinger when there is a clear secondary gain or as part of a factitious disorder. Detecting a case of factitious disorder imposed on another requires a practitioner to mentally shift his or her thinking to consider this possibility because it is difficult to accept that a caregiver might misrepresent, simulate, or cause signs of illness in her children. Suspected cases of factitious disorder are best managed by all of a patient’s practitioners communicating directly with one another about their concerns, consulting local experts in this topic, and then arriving at a unified rather than divided approach to helping the child.

Sleep Problems

Sleep problems are very common, present in 5%–20% of children (Meltzer et al. 2010). Most childhood insomnia can be traced to poor sleep habits and inadequate enforcement of bedtime habits by caregivers. The contemporary incorporation of electronics into every aspect of daily life means that it is no longer sufficient for practitioners to simply recommend no television in the bedroom of a child with insomnia. Cell phones have effectively become sleep prevention devices 44through the applications, text messaging, and games they bring into the bedroom. Restricting all computer access and video game use after a certain time in the evening can yield a dramatic improvement in the amount of sleep that children (and their caregivers!) get.

Another key sleep hygiene problem is a loss of the behavioral association that being in bed equals sleep time. Behavioral routines around going to bed help signal to the brain when it is time to disconnect. Doing homework in bed, eating in bed, playing in bed, and communicating with friends from bed break that behavioral association. For those with insomnia, the act of lying awake in bed for a long time, staring at the clock, and waiting for sleep can become another sleep-interfering behavior. If sleep does not come quickly, the behavioral association of bed equals sleep is improved by getting out of the bed for a nonelectronic “quiet and boring” activity such as sitting in a chair to read and returning to bed only when feeling sleepy. A list of sleep hygiene practices appears in Chapter 14, “Psychosocial Interventions.”

Sleep is also impaired by distracting thoughts, worries, or symptoms of many different DSM-5 conditions (Table 3–8). Addressing problems such as maltreatment, PTSD, anxiety, and mood disorders can significantly improve sleep. In some cases, insomnia worsens or perpetuates a mood disorder to such a degree that using a medication for the restoration of adequate sleep can be a way to help resolve that mood disorder more quickly.

Reasonable bedtimes may be a sticking point worth addressing. Caregivers cannot expect adolescents to fall asleep at 8:00 P.M. every night, even though that may be a reasonable expectation for younger children. For children with long-term sleep phase advancement problems, such as rarely falling asleep before 3:00 A.M., changing bedtimes too quickly does not work because it takes weeks to retrain the circadian rhythm and behavioral associations with sleep.

Obstructive sleep apnea also can have negative psychiatric effects; thus, when apnea is found in a (typically obese) child through polysomnography, a sleep apnea treatment also may improve other psychiatric symptoms. When the tonsils are large, a simple tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy may be helpful. Any more extensive surgical intervention on the palate or pharynx of a growing child should be viewed with much greater skepticism because of higher rates of complications. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) systems can be effective and safe for sleep apnea treatment, but it is typically quite difficult to get a child to actually use a CPAP machine every night—far more often, these systems are purchased but not used. Notably, with severe sleep apnea, potent sedatives such as benzodiazepines at night would not be recommended.

45TABLE 3–8. Sleep problems

Diagnostic category |

Suggested screening questions |

First consider |

|

Abuse |

“Has anything or anyone made you feel uncomfortable or unsafe?” (for caregiver) “Has anything happened to your child that really shouldn’t have happened?” |

Bullying |

“Have other kids been teasing you or making you feel afraid?” |

Poor sleep habits |

“What is your routine before going to bed? |

Common diagnostic possibilities |

|

Generalized anxiety disorder |

“Do you feel tense, restless, or worried most of the time? Do these worries keep you awake?” |

Insomnia disorder |

“Have you had difficulty with sleep 3 or more nights a week for at least the past 3 months?” |

Major depressive disorder |

“Have you felt really down, depressed, or uninterested in things you used to enjoy for more than 2 weeks?” |

Posttraumatic stress disorder |

“Do you avoid reminders of traumatic events in your past? Do you startle easily or get frequent nightmares?” |

Parents and patients often ask for a prescribed medication to help with sleep. The challenges of this strategy include limitations in effectiveness, creating psychological associations that one cannot sleep without a pill, physiological dependence 46or tolerance, and exposure to unwanted adverse effects. After sleep hygiene measures fail, for moderate to severe insomnia we consider a medication. The core principle should be to favor nonaddictive, safe, and low–side effect sedative options with children. The secondary principle is that if a child has insomnia plus another psychiatric disorder, selecting a medication that can address both conditions at once is preferred to using multiple medications.

Antihistamines are a reasonable first-line option because of their safety profile. Melatonin, up to 5 mg nightly, is considered generally safe, but at least theoretical concerns exist for the negative effects it may have on other hormone systems. More potent sedative options include the α-agonists (clonidine, guanfacine), which, when administered nightly, could help with sleep in addition to other conditions such as ADHD. Anxiety that continues to cause insomnia despite the use of SSRIs and CBT may benefit from hydroxyzine as a nonaddictive option or an off-label trial of a sedating antidepressant such as mirtazapine. In severe cases, a low dose of a benzodiazepine or an off-label benzodiazepine analogue (zolpidem, zaleplon) might be necessary to achieve results. For children requiring an antipsychotic to treat their psychiatric disorder, a sedating option such as quetiapine or risperidone taken at bedtime may improve the comorbid insomnia. Use of an antipsychotic solely as a sleep aid is inappropriate and unsafe (McVoy and Findling 2013).

Self-Harm and Suicidality

Suicidality and self-harm behaviors are very common among adolescents, more common than most of us realize (Table 3–9). In research surveys, 14%–24% of adolescents self-reported that they have committed an act of self-harm, and about 6%–7% stated that they have made a suicide attempt in the previous year (Lewis and Heath 2015). Thankfully, completed suicides are far more rare than the number of suicide attempts. You are more likely to get full and honest answers about suicidality and substance abuse when interviewing a young person away from his or her caregivers, so ask for privacy before you ask about self-harm.

Asking young people if they feel suicidal can be awkward until you become accustomed to asking about it. Despite the awkward feelings, these questions cannot be avoided. Because suicide is one of the three leading causes of death among the young, asking a young person about feelings of suicide is just as important as screening an adult for chest pain or shortness of breath.

47TABLE 3–9. Self-harm and suicidality

Diagnostic category |

Suggested screening questions |

First consider |

|

Risk acuitya |

“Have you ever thought about hurting yourself or taking your own life? Have you ever done something to hurt yourself or tried to kill yourself? Do you have any plans now for how you would kill yourself?” |

Current triggersa |

“Do you have any recent relationship problems or big disappointments?” |

Current supportsa |

“Do you have anyone in your life who helps support you?” |

Access to lethal meansa |

“Can you easily get a gun or enough pills that you think could kill you?” |

Common diagnostic possibilities |

|

Bipolar disorder |

“Has there ever been a period of a week or more when you were the opposite of depressed, with super high energy and little need for sleep?” |

Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia) |

“Have you felt persistently sad or gloomy for more than a year?” |

Major depressive disorder |

“Have you felt really down, depressed, or uninterested in things you used to enjoy for more than 2 weeks?” |

Substance use disordera |

“Have you been using drugs or alcohol?” |

aThese questions should be asked when the patient is alone.

48If you fear that asking about suicide creates risks, allow us to put your mind at ease. Asking about suicidal thoughts, plans, and past actions not only gathers essential diagnostic information but also shows your concern. For a self-harming or suicidal young person, having an adult in her life who communicates that she cares about her is therapeutic.

When asking about suicidality, we suggest starting with broad questions, then getting specific. Asking “Have you ever...” risk questions before “How about now...” questions just flows better conversationally. If you uncover self-harming or suicidal behaviors, continuing to ask questions about previous suicidal behaviors (the strongest predictor of future behavior), current self-harm plans, and current stressors is key to being able to understand the immediacy of any risks. If you learn that the adolescent tried to avoid premature discovery of a suicide attempt, such as hiding emptied pill bottles, this would be very concerning. Easy, impulsive access to lethal means, such as a loaded firearm, is another major risk factor.

Recurrent self-harm behaviors, such as cutting, are often cited by young people themselves as a coping mechanism that they perform in part to reduce their risk of suicide. However, recurrent self-harm increases the risk for future suicidal behaviors.

The strongest predictors of a future suicide completion are a history of suicide attempts, an active mood disorder, current substance abuse, and a family history of suicidal behavior. For adolescents in particular, suicide attempts are often triggered after an acute loss or disappointment, such as breakup with a boyfriend or girlfriend or an acute family conflict. Nearly 90% of adolescent suicide deaths occur from firearms or suffocation, which includes hanging, so suicidal plans involving these strategies are the most concerning (Eaton et al. 2008). Suicide attempts by overdose are much more common but are also much less likely to be lethal.

After learning both the general and the specific details of the situation, we suggest keeping in mind a prudent layperson standard for when to consider an acute hospitalization. Child mental health specialists are not really much better than anyone else would be in assessing risks once all the details of the situation are known. The difference is that child 49mental health specialists excel at eliciting the details of a situation. The key is to keep asking for more information to flesh out the whole situation rather than stopping your inquiries at “they said they feel suicidal.” You should consider hospitalization for any young person who appears to have a significant safety risk after you elicit the details of the situation. Psychiatric hospitalization keeps a patient physically safe for at least a short time while initiating further steps in her care.

Young people with recurrent self-harm behavior or significant suicidal thoughts should be referred for psychotherapy because this is clearly the most effective treatment available. If a family declines to use counseling with a mental health professional, you can also encourage the use of as many other social supports and supervision arrangements as possible.

Medications do not have a significant role in reducing suicide or self-harm risks on a short-term basis. However, if a child has major depressive disorder or an anxiety disorder, then long-term suicide risks can be reduced through successful treatment with SSRIs. See Chapter 15, “Psychotherapeutic Interventions,” for more information about SSRI use and suicidality. For a severe depression, the greatest treatment responses occur when SSRIs are combined with psychotherapy. Frequent monitoring and making the environment safe (i.e., restricting access to dangerous medications and firearms) are advised for all suicidal young people.

Substance Abuse

The key to making any diagnosis is thinking of the possibility, which can be a challenge when it comes to adolescent substance abuse (Table 3–10). When we see fresh-faced, youthful adolescents in our offices, we can find it hard to simultaneously view them as possible substance abusers. The available statistics dictate that we do so. In the United States alone, national surveys show that past-month adolescent alcohol use rates in the United States are about 9% of 14 - to 15-year-olds and 23% of 16- to 17-year-olds, and for marijuana, about 7% of 12- to 17-year-olds report past-month use. Cocaine, hallucinogens, and inhalants are also abused by adolescents but at rates of less than 1% (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014).

50TABLE 3–10. Substance abuse

Diagnostic category |

Suggested screening questions |

First consider |

|

Safetya |

“Have you ever been in a car driven by someone who was drunk or high? Have you injured yourself while you were drunk or high? Have you blacked out or done things you regret while drunk or high?” |

Common diagnostic possibilities |

|

Substance use disordera |

“Have people asked you to cut down on drinking or using drugs? Do you ever drink or use drugs when you are alone? Do you get strong cravings or end up using more than you wanted to?” |

Substance withdrawal |

“Do you get more moody or anxious while your alcohol or drugs are wearing off?” |

Substance tolerance |

“Has the same amount of drug or alcohol been losing its effect over time?” |

Substance/medication-induced mental disorder |

“Did you develop more mood or anxiety problems after you started using?” |

“Self-medication” role of substances |

“Are there any problems that you wanted the alcohol or drugs to resolve?” |

aThese questions should be asked when the patient is alone.

Recognition starts with remembering to ask about substance use and ideally doing so without a parent in the room. We prefer to ask parents to leave the room for this aspect of the encounter and openly reemphasize applicable confidentiality rules during the separation process. Generally, everyone will understand the concept of maintaining confidentiality unless a major safety risk exists, such as having blackouts or driving while intoxicated. This same one-on-one time can be used to discuss other sensitive topics such as self-harm and suicidality.

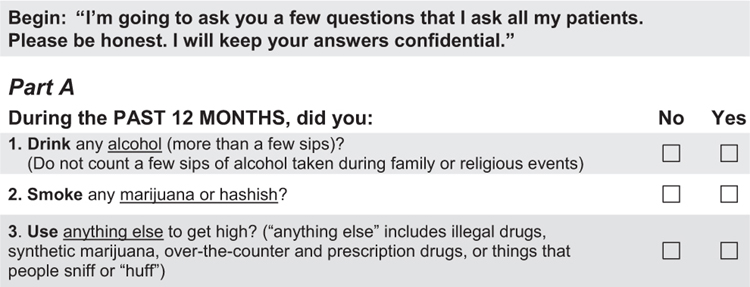

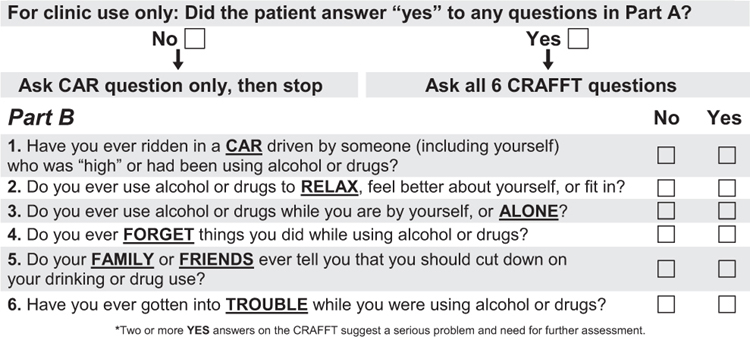

51A widely recommended screening tool for adolescents is the CRAFFT (Figure 3–1), which the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends using during adolescent health maintenance appointments (Yuma-Guerrero et al. 2012). If two or more question answers are positive, there is a high chance of a substance use disorder being present (Knight et al. 2002).

Urine drug testing may help to evaluate the cause of an acute intoxication or may be used for tracking care within a specialized substance abuse treatment program. However, we do not otherwise recommend urine drug testing as a part of routine care because it can unnecessarily diminish the therapeutic alliance.

In the past, the emphasis was on needing to determine whether a patient’s substance use represented abuse or dependence. Because this differentiation was often unclear and carried both stigma and legal ramifications, these separate dependence and abuse diagnoses were merged into a single substance use disorder diagnosis in DSM-5. The hallmarks of a substance use disorder include loss of control over one’s use, social impairments, use in risky situations or despite negative consequences, and physiological changes of tolerance or withdrawal. In other words, not all adolescents who use substances have a disorder.

You should be alert to symptoms caused by substance abuse that look like another psychiatric illness. Sedative drugs (hypnotics, anxiolytics, and alcohol) can cause depression during intoxication but anxiety during withdrawal. Stimulating drugs (amphetamines, cocaine) can cause psychosis and anxiety during intoxication but depression during withdrawal. Both drug classes cause sexual and sleep disturbances. Psychotic symptoms may occur from anticholinergics, cardiovascular drugs, steroids, stimulants, and depressants. Marijuana can cause depressed mood and anxiety, even though adolescents claim that it treats their depression or anxiety. In an adolescent vulnerable to psychosis, marijuana can trigger persisting psychotic symptoms (van Nierop and Janssens 2013).

When substance-created psychiatric symptoms are possible, we motivate the adolescent to do a self-test of not using for a specific period of time (e.g., at least 2 weeks) to see what happens. Most substance-induced mental disorders will improve after a few weeks of abstinence. For adolescents who say “I can stop whenever I want to,” we would follow this statement by empowering them to do just that for the reasons that make the most sense to them. This does two things: 1) it determines whether their symptoms really are substance induced, and 2) if they cannot go more than 2 weeks without using, then it highlights their lack control over their use.

52

53

FIGURE 3–1. The CRAFFT Screening Interview.

Source. © John R. Knight, MD, Boston Children’s Hospital, 2015. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission. For more information, contact ceasar@childrens.harvard.edu.

54Care of a substance use disorder is based on educating adolescents about the negative outcomes from use, helping them learn their triggers and motivating reasons to use, building motivation for change, and shaping family involvement in resolving the problem. Motivational interviewing, CBT, family therapy, supervised peer groups, mindfulness training, identifying triggers (to avoid future cue-based use), changing peer groups, and arranging for rewards for evidence of sobriety are all specific outpatient care options.

Disturbed Eating

Eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia can present a diagnostic challenge in that young people who have become significantly ill with an eating disorder generally try to hide their symptoms, even when asked directly by a trusted person (Table 3–11). With low-weight anorexia nervosa particular, withholding information or even lying to practitioners often happens in the service of maintaining disordered eating. Therapists sometimes refer to these lies as the eating disorder, rather than the patient herself, doing the talking. Because of this inconsistency, collateral informants (i.e., parents and other caregivers) are typically very helpful for understanding the extent of symptoms and behaviors. An investigative approach helps. When you learn that a young person who denies self-induced vomiting goes to the bathroom immediately after most of her meals, you should explore the possibility of disturbed eating and body image. Remember that young people with eating disorders often show rigid thinking and perfectionism.

Postpartum Maternal Mental Health

Maternal peripartum depression is common, even more so in developing countries (about 1 in 5) than in developed countries (about 1 in 10) (Paschetta et al. 2014). The risk that the mother of a newborn will experience depression increases with stressors such as poverty, lack of partner support, unwanted pregnancy, and domestic violence. When a woman has depressive symptoms during her pregnancy, the chances that she will develop postpartum depression increase, so we counsel increased vigilance for these parents.

55TABLE 3–11. Disturbed eating

Diagnostic category |

Suggested screening questions |

First consider |

|

Medically induced weight loss |

“Have you had recurring diarrhea?” (inflammatory bowel disease) Have you been losing weight despite wanting to maintain?” (endocrine disorder/malignancy) |

Self-harma |

“Have you been thinking about hurting yourself? Have you ever hurt yourself or attempted suicide?” |

Common diagnostic possibilities |

|

Anorexia nervosa |

“Do you worry about losing control when you eat? Do you prefer to eat alone? “ (on growth curve: an unexpected loss of weight or failure to gain appropriately) |

Bulimia nervosa |

“Have you had recurring times when you overeat and then feel the need to compensate afterward? Do you use laxatives or vomit after meals?” |

Major depressive disorder |

“Have you felt really down, depressed, or uninterested in things you used to enjoy for more than 2 weeks?” |

Substance use disordera |

“Have you been using drugs or alcohol?” |

aThese questions should be asked when the patient is alone.

Postdelivery obstetric care for mothers and the first year of health maintenance care for children ideally include some 56form of screening for maternal depressive and anxiety problems (Table 3–12). You can accomplish this by conversationally asking the mother about her psychological well-being (which helps to communicate its importance) and can supplement this approach with a brief rating scale screen (such as the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item or Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale) in routine office care. Fatigue and poor sleep, which are often associated with parenthood itself, need to be recognized as potential signs of an episode of major depressive disorder.

Good parental mental health is important for children. When parents struggle, there can be negative effects on the child’s physical state (poor health, poor weight gain), cognitive status (delayed acquisition of milestones, impaired attention), social development (ODD, conduct problems), behavior (more crying, irritability, and temperament challenges), and emotional development (depression, anxiety) (Satyanarayana et al. 2011). In rare instances, a parental mental health condition can become so severe, such as developing psychosis, that a parent will actually harm her child.

Treating parental mental health problems during a child’s early development phase has been found to have positive effects on child mental health. When a parent or other caregiver with mental illness receives care, this also greatly increases the chance that the child will develop an easygoing temperament, which will pay dividends in the household for years (Hanington et al. 2010).

Treating a parent or caregiver begins with addressing life stressors ranging from mild (keeping up with laundry or cleaning) to severe (loss of employment, poor relationship with partner). Rallying a parent’s personal care system to support her and take her distress seriously may be sufficient to produce positive change. Psychotherapy is indicated for any situations in which major depression, GAD, or another significant disorder has set in.

The decision to use psychiatric medications postpartum is similar to what one would choose at any other time for mental health treatment. The degree of psychiatric medication transmission through breast milk is typically too low to generate any effects on a breast-feeding child, with the notable exception of lithium (Davanzo et al. 2011). Moderate to severe depression generally responds most quickly to a combination of SSRIs and psychotherapy, so this should be the usual approach (Lanza di Scalea and Wisner 2009).

57TABLE 3–12. Postpartum maternal mental health

Diagnostic category |

Suggested screening questions |

First consider |

|

Suicidality |

“Have you been having thoughts about hurting yourself?” |

Psychosis |

“Have you been hearing voices or feeling worried that your mind is playing tricks on you?” |

Child safety |

“Have you felt worried that you might intentionally hurt your child?” |

Common diagnostic possibilities |

|

Anxiety disorder |

“Do you feel tense or worried most of the time? Do worries affect your sleep?” |

Major depressive disorder |

“Have you felt really down, depressed, or uninterested in things you used to enjoy for more than 2 weeks?” |

Medication choices during pregnancy itself have to be weighed a bit more carefully against the potential effects a specific medication may have on a developing fetus. The traditional advice was to avoid lithium because of the risk of Ebstein’s anomaly, but recent research (Pearlstein 2013) identifies those congenital defects of the tricuspid valve as more rare than previously believed. Lithium may be prescribed, with caution and counseling, during pregnancy. We do, however, advise against the use of valproate, a known teratogen whose maternal use is associated with neurodevelopmental disorders in children. The rare, but well-reported, risk of low birth weight or pulmonary hypertension of the newborn from SSRI use during pregnancy means that SSRIs should be reserved for more severe cases of depression and anxiety (Pearlstein 2013).

Any time a parent develops psychosis or suicidality, a hospital admission level of care should be considered. 58