Understanding Intuitive Decision Making

Many of the decisions we make in life are grounded in logic, the product of thoughtful and careful consideration. On the other hand, there are those choices you make without any real analysis or considered reason. Such choices are often made without conscious awareness, as when you decide what to eat, what to wear, or what movie to watch.

In his bestselling book Thinking, Fast and Slow, psychologist Daniel Kahneman, co-winner of the 2002 Nobel Prize for economics, suggests that intuitive decision making is the “secret author of many of the choices and judgments [we] . . . make.” The idea that you can make decisions about what is best for you based on intuition or gut feelings—as opposed to donning a rational thinking cap—is central to the human condition.

In fact, that kind of nonrational decision making has played a central role in my own life. When I was seventeen years old, I worked after school at the family business, my parents’ confectionery shop in the Bavarian Alps. It was an idyllic place to grow up, in the middle of a major skiing and hiking area, and only a few hours’ drive from Italy. The shop was founded by my great-grandfather in 1887 and it had been owned and run by my family ever since. As a teenager, I made pastries and cakes for all kinds of occasions and particularly loved whipping up fancy chocolates into exotic shapes and sizes. It was there that I learned to associate certain aromas with different seasons and holidays, laying the basis (without any conscious awareness on my part) for my future career in studying the intricate dialogue between food, the gut, and the brain.

When it was time to decide about college, I agonized for months between becoming a fifth-generation confectioner or pursuing a career in science and medicine. On the one side, there were the attractions of taking over a well-established and lucrative business—staying connected to a closely knit community, living near friends and family, and being able to spend my free time in the town’s beautiful landscape. There were also the expectations of my father, who had always planned that I would continue the proud family tradition. On the other hand, I felt pulled in a totally different direction: a rejection of traditions and routines, a love for reading books, in particular those dealing with psychology, philosophy, and science, and an insatiable curiosity about the scientific underpinnings of the mind. Unable to choose based on a list of pros and cons, I began for the first time in my life to listen to my gut feelings.

Ultimately, to the great disappointment of my father, I decided to leave the family business behind and begin my studies in Munich. When I finished medical school several years later, another gut-based decision pulled me even farther away from home and from the established career path of a German university professor, when I rejected a coveted residency training position at the university hospital in Munich and joined a research institute in Los Angeles, the Center for Ulcer Research and Education, known by its acronym CURE. The center had become a magnet for researchers from around the world interested in learning about the gut-brain dialogue. After the first few days in the lab, it became very clear that my new activities—purifying and testing various molecules from pig intestines we collected in the slaughterhouse—had none of the charms of the chocolate factory back home.

However, I became fascinated with my new work when I slowly realized that the implications of my research weren’t limited to the gut: the identical signaling molecules we were isolating from the pig intestines were also found in the brain, and they were also used by a wide range of plants, animals, exotic frogs, and yes, even bacteria, to communicate with each other—a fact that has become known in science-speak as interkingdom signaling. Little did I know that this area of brain-gut communication would occupy my scientific interest for the rest of my medical career.

While my gut feelings had a profound influence on my life, the reality is that the stakes were not all that high. I was given many opportunities in those early years to explore different paths—and chances are, I could have been happy with whatever I’d chosen. But for others, gut decisions can be a matter of life and death.

On September 26, 1983, a young duty officer in the Soviet Air Defense Forces, Stanislav Petrov, was stationed in a bunker outside Moscow when Soviet satellites mistakenly detected five U.S. ballistic missiles heading toward the USSR. Even though alarm bells sounded, and a screen flashed “LAUNCH,” Petrov made the monumental decision that the alarm was false and refused to confirm the incoming strike. Had he acted upon the “rational” procedures that were put in place for such a situation (like many of his military colleagues might have done), his retaliatory strike would have been followed by a U.S. retaliation, in all likelihood causing many millions of deaths.

Petrov initially gave several rational explanations for his decision, including his belief that an attack by five missiles didn’t make sense. Any U.S. strike would be massive, with hundreds of missiles. Moreover, the launch detection system was new and, in his view, not yet wholly trustworthy. Finally, ground radar failed to confirm the attack.

However, in a 2013 interview, when it was safer to make such an honest statement, Petrov said he was never sure that the alarm was erroneous, but that he made his decision on “a funny feeling in my gut.”

People the world over refer to gut-based decisions in a similar way. It does not seem to matter what type of decision is being made—political, personal, or professional, whom to marry, what college to attend, what house to buy. Presidents ultimately make gut-based decisions about war and peace, affecting millions of people, after they have listened to their advisors and carefully weighed the options on the table. If it’s important, humans listen to their gut.

Gut feelings and intuitions can be viewed as opposite sides of the same coin. Intuition is your capacity for quick and ready insight. Often you know and understand things instantly, without rational thought or inference. You feel when something’s fishy. You sense when you have an instant personal bond with a stranger. You are positive that the charismatic politician on television is lying through his teeth. Gut feelings reflect an extensive and often deeply personal body of wisdom that we have access to, and that we trust more than the advice provided by family members, highly paid advisors, and self-declared experts or social media.

So exactly what is a gut feeling? What’s its biological basis? And what role do the signals originating in the gut have in the generation of gut feelings? In other words, when does a gut sensation become an emotional feeling?

Some answers can be found in the extraordinary work of Bud Craig, a neuroanatomist who has advanced our understanding of the circuitry that allows your brain to listen to your body and vice versa. His ideas, laid out in a recent book, How Do You Feel? An Interoceptive Moment with Your Neurobiological Self, have played an important role in my own research, which looks at how your brain listens to your gut and the microbes that live in it (and vice versa).

The complex neurobiological process by which our brain constructs subjective gut feelings from the vast amount of information it receives in the form of gut sensations 24/7 is the foundation for the subjective experience of how we feel the moment we awake, after we eat a delicious meal, or endure a prolonged fast. There is growing evidence to suggest that the constant stream of interoceptive information from the gut (including the chatter of our gut microbiota) may play a crucial role in the generation of our gut feelings, thereby influencing our emotions.

Feelings (including gut feelings) are sensory signals that tap into your brain’s so-called salience system. Salience is the level to which something in the environment can catch and retain one’s attention, because it is important or noticeable; something that stands out. A bee buzzing around your head while you read this chapter may command more of your attention than the contents of the chapter, in particular because there is the potential threat of the bee stinging you. A thunderstorm outside may have similar salience and be equally effective to focus your attention away from the book, while background music playing at a low volume, or the sounds of a gentle breeze outside, may go unnoticed. The brain’s salience system appraises the relevance of any signal regardless of whether it comes from your body or from the environment, to the point where the signal enters our attentional processes and our consciousness.

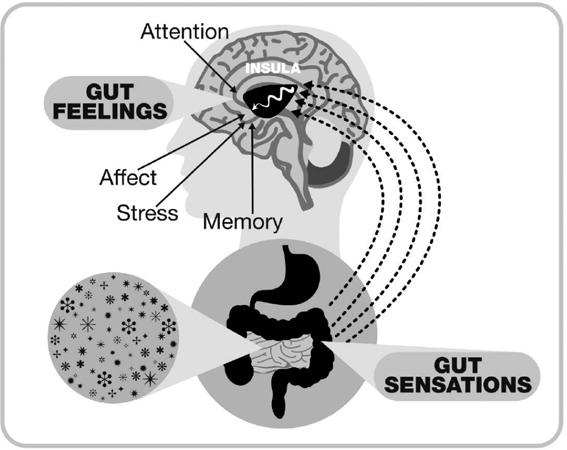

FIG. 6. HOW THE BRAIN CONSTRUCTS GUT FEELINGS FROM GUT SENSATIONS

Signals arising from the gut and its microbiome, including chemical, immune, and mechanical signals, are encoded by a vast array of receptors in the gut wall and sent to the brain via nerve pathways (in particular the vagus nerve) and via the bloodstream. This information in its raw format is received in the back portion of the insular cortex and then processed and integrated with many other brain systems. We only become aware of a small portion of this information in the form of gut feelings. Even though they originate in the gut, gut feelings are created from the integration of many other influences, including memory, attention, and affect.

High-salience events related to gut sensations (including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea) are usually accompanied by emotional feelings of discomfort and sometimes pain, alerting us that something important is going on that requires attention and a behavioral response. However, gut feelings can also be associated with positive gut sensations, such as feeling good and satiated after a nice meal, or the pleasant sensation experienced in the pit of the stomach in a fully relaxed state. The threshold for what your brain appraises as salient is influenced by many factors, including your genes, the quality and nature of your early life experiences, your current emotional state (the more anxious you are, the lower will be the salience threshold), your mindfulness of body sensations, and your vast memories of emotional moments, acquired over a lifetime. But remember, in terms of signals originating in our digestive system, most of the time your salience system operates below the level of conscious awareness. Trillions of sensory signals rise up from your gut every day and are processed in your brain’s salience network, yet most don’t attract your attention. They remain below the surface, content to percolate into your subconscious.

How does the salience system decide which one of these signals becomes a consciously perceived gut feeling? One brain region that plays a crucial role in this process is the insular cortex, which is the central hub of the brain’s salience network. The insula, as it is also known, was given its name because of its location as “a hidden island” beneath the temporal cortex. In a theory based on neuroscientist Bud Craig’s paradigm-shifting concepts and a wealth of scientific data, different regions of this hidden island in our brain are thought to play specific roles in recording, processing, evaluating, and responding to interoceptive information. According to the current understanding of how the brain handles this tremendous task, the representation of the primary image of our body is first encoded in a netork of nuclei located in the lowest part of the brain, the so-called brainstem. From there, much of this information reaches the back part of the insulaar cortex. There our perception of this image is comparable to a grainy black-and-white picture that reflects the state of every cell in our body, yet is barely visible to the naked eye.

Actually, our brains are not really interested in our comments on this information, so this raw image is not intended for our viewing pleasure. The information contained in it is relevant mainly for routine, steady-state feedback by the brain to the body region where the information originated—in our case, the gastrointestinal tract. In theory, the National Security Agency handles data the same way. In a perfect world, no one would access any of the agency’s stored information unless a salience threshold were breached, alerting security agents to scrutinize telephone, Internet, and travel patterns.

The insular image is then refined, edited, and colored, similar to the process an actor’s or actress’s head shot undergoes after a film shoot. What Craig calls the “re-representation” of the interoceptive image of your body into ever-more-refined image versions can be compared to the process that is used in professional photography. Like a photographer using Photoshop, the brain uses affective, cognitive, and attentional tools as well as memory databases of previous experiences to refine the quality and salience of the image. As the editing progresses, the brain’s attentional networks become more engaged, causing us to become more aware of the image and associate it with motivational states—that is, a drive to do something in response to the feeling being generated. It is where your visceral sensations and gustatory experiences are sent to in your brain, allowing you to feel the need to eat or eliminate, rest or run, save energy or expend energy. Once this process reaches the frontal part of the insular cortex, the image has all the features of a conscious emotional feeling that describes the state of your whole body and that we are connecting to our sense of self: feeling well, feeling nauseated, feeling thirsty, hungry, or satiated, feeling relaxed, or simply feeling unwell. From a neurobiological viewpoint, these are our true gut feelings. Despite its central role in this process, it is important to remember that the insula doesn’t handle this remarkable task in isolation, but does it in close interactions with other parts of the brain’s interoceptive network. This network includes several nuclei in the brainstem and different regions of the brain’s cortex.

But what does our brain do with the myriad gut feelings we have accumulated over a lifetime? It would hardly make sense that evolution has come up with such an amazingly complex data-gathering and processing system, only to throw the collected information away. This library of gut feelings is composed of an enormous amount of personal and salient information about each of us that has been collected every second of the day, 365 days a year. The current scientific thinking is that this information is stored in an exponentially growing database, analogous to data collection systems created by companies and government agencies. The data collected in our brains is about highly personal experiences, our motivational drives, and our emotional reactions to these experiences, which our brains have been constructing since birth and maybe even in utero. Even though most people have paid little attention to this process or thought about its implications, we will see that it has a great deal to do with gut-feeling-based decision making.

This stored information represents countless positive and negative emotional states that we have experienced in our lifetime. For example, emotional memories may be associated with negative outcomes of decisions we have made, such as the awful abdominal pain and discomfort I experienced in Manali. This database archives the butterflies we experience in our stomachs before a job interview, or the knot that forms in the pit of our belly when we are really angry or personally disappointed. Such markers may also be associated with the pleasure of a delicious meal or the intense feelings of romantic love, or the feeling of empowerment.

Individual Differences

Pretend you are a participant in an experiment designed to look at the relationship between interoception and emotional intelligence. You lie down in a brain scanner, put on headphones, and place your left middle finger on a pad that monitors your heart rate. Your right hand rests on another pad with two buttons. As the scanner monitors your brain activity, you listen through the headphone to several series of ten beeps. After each ten-beep sequence there is a pause and you are asked to make a choice: press one button if you think the beeps were in time with your own heartbeats, or press the other button if you think the beeps were slightly out of sync with your heart. You will hear these sequences repeated, sometimes in sync, sometimes not. Can you tell the difference?

When this experiment was carried out several years ago on nine women and eight men, four subjects were supremely confident about when the pulse was synchronous or asynchronous with their hearts. They could feel the difference, accurately, every time. Two subjects were veritably heart blind. They never had a clue about whether the pulses were in or out of sync, and could only guess at random. The others fell in between.

Brain scans revealed significant activity in several brain regions of all of the participants, notably the right frontal insula. It showed the greatest activity in those who were best at following their heartbeats. Most important, these were the people who scored highest on a standardized questionnaire to probe their empathy levels. So the better you are at tracking your own heartbeats, the better you are at experiencing the full gamut of human emotions and gut feelings. The more viscerally aware, the more emotionally attuned you are. Even though this study was done with a focus on sensations from the heart, there is no reason to doubt that it would equally apply to the awareness of gut sensations.

Early Development

Gut feelings and moral intuitions have an interesting origin, related to, of all things, food. Hunger is an early emotion related to survival. And it is foundational to all the gut feelings you experience later in life, including your sense of right and wrong.

Let me explain with a story. My wife and I recently hosted some close friends for the weekend, along with their adult daughter and seven-month-old granddaughter, Lyla, who babbled most of the day. The baby was happy much of the time, but her smile and obviously good mood were interrupted whenever she got hungry, tired, or was about to fall asleep. We now know that the gut-brain axis at age seven months is a work in progress, particularly in terms of full brain development and the salience network. Moreover, gut microbes are not fully established until the end of the third year of life. Still, Lyla’s primitive salience network was tuned to gut sensations related to hunger and this led to lusty crying that got her the milk she wanted. Once she was fed, Lyla’s initial aversive gut feeling was quickly replaced by one of comfort and pleasure, triggered by new gut sensations related to satiation.

My main point: gut feelings related to hunger comprise your earliest signals about what is good and bad in the world, and they begin at birth. The gut feeling of an empty stomach may be a newborn child’s first negative proto-emotion, triggering an uncontrollable craving for food. Similarly, the satiated feeling that follows the consumption of breast milk—which is full of prebiotics and probiotics—is likely the earliest experience of feeling good. Other positive gut feelings include gentle touch (part of interoception) with Mom, as well as warmth and comforting sound.

The signals sent from your gut to your brain, the gut sensations, play a key part in these early experiences and, by extension, your ability to differentiate good from bad. When your stomach was empty, it released a hormone, ghrelin, that led to an urgent feeling of hunger. This sensation, coupled with a strong motivational drive, would be the basis of other bad gut feelings.

Gut feelings can also be associated with positive sensations, such as the warmth of feeling full after a good meal, the pleasant sensation in the pit of your stomach while practicing abdominal breathing, or smelling chocolate aromas in a family confectionery.

The cycling experience in infancy of feeling full or hungry—good or bad—may lay the foundation for the moral judgments of good and bad that emerge into gut feelings later in life. In other words, your gut registered how well your needs were met or not met in infancy. A hungry baby left in its crib to cry for an hour perceives the world very differently from the baby who is quickly picked up, cradled, and fed. Thus your earliest gut feelings serve as a model for “what the world is like and what I must do to survive in it.”

Sigmund Freud intuited as much when he developed his pragmatic understanding of primary motivational forces. The great psychiatrist linked psychological and character development to the infant’s fixation on the “entry and exit” regions of the digestive tract—his famous “oral” and “anal” phases of psychic development. But Freud missed the crucial contribution of feelings, constructed by the brain based on sensory information coming from the entire digestive tract and its resident microbes—something we are only now beginning to appreciate.

How do the vast assemblies of gut microbes contribute to these early feelings of “good” and “bad”? Recall that your body is host to trillions of microbes that outnumber all of the human cells in your body. They live pretty much everywhere—on your skin, between your teeth, in saliva, in your stomach, and—most relevant to gut feelings—in your gastrointestinal tract. Your gut is home to more than a thousand microbial species that are, at multiple levels, talking to your brain.

Based on emerging evidence about the development of the gut microbial ecology during the first three years of life, we can make some intriguing speculations. It’s plausible from animal studies that gut microbes influence the emotional state and development of infants the world over, from crying to cooing.

How? Some of it has to do with mother’s milk, which contains something akin to Valium. The gut microbes in all infants are adapted to optimally metabolize the complex carbohydrates in breast milk. One of the microbes best suited for this is a certain strain of lactobacillus that makes a metabolite of GABA—a substance that acts on the same brain receptors as the anxiety-reducing drug Valium. By producing endogenous Valium, a microbe may help to calm down babies’ emotion-generating system in the brain, and make them feel good by relieving them of hunger pangs.

Human breast milk also contains complex sugars that are not only essential for the baby’s developing gut microbiome, but may also contribute to a baby’s sense of well-being when it’s fed. When newborn rats are fed sugar water, sweet-taste receptors in the gut and mouth generate sensations that are processed by the brain. These lead to the release of endogenous opioid molecules that reduce pain sensitivity, and presumably make rodents feel pretty good. The same may be true for human infants.

What Makes Our Brains Uniquely Human

In all the talk about what makes humans special, you’ll hear many of the same arguments. We walk upright. We have opposable thumbs. Our brains are enormous. We have language. We’re top predators. But there are two features of our brains that are most relevant to our discussion about gut feelings and intuitive decision making.

The size and complexity of the frontal insula region and the closely connected prefrontal cortex—the hub of the salience network and the site where our gut feelings are created, stored, and retrieved—is what most distinguishes us from all other species. The animals closest to us in terms of relative size of their anterior insula are some of our simian cousins, in particular certain species of gorillas, followed by whales, dolphins, and elephants—all widely recognized for their emotional, social, and cognitive brain capabilities and, not coincidentally, their Animal Planet popularity.

However, there is another feature particular to the human brain that you’ve probably never heard about. Tucked into your right frontal insula and its associated structures lies a special class of cell found in no other species except great apes, elephants, dolphins, and whales. Called von Economo neurons (or briefly VENs), after the scientist who first observed them in 1925, they are big, fat, highly connected neurons that appear to be in the catbird seat for enabling you to make fast, intuitive judgments.

You can make snap judgments because your brain contains VENs, but to keep things simple, let’s call them intuition cells. A very small number of intuition cells showed up in your brain a few weeks before you were born. Studies suggest that you probably had about 28,000 such cells at birth and 184,000 by the time you were four years old. By the time you reached adulthood, you had 193,000 intuition cells. An adult ape typically has 7,000.

Intuition cells are more numerous in your right brain. Your right frontal insula has 30 percent more than your left insula. Intuition cells appear to be designed to relay information rapidly from the salience network to other parts of the brain. They contain receptors for brain chemicals involved in social bonds, the expectation of reward under conditions of uncertainty, and for detecting danger, as well as for certain gut-based signaling molecules such as serotonin—all ingredients of intuition. When you think your luck is about to change while playing blackjack, these cells are active.

John Allman, a neuroscientist at Caltech and a leading expert on the VENs, says that when you meet someone, you create a mental model of how that person thinks and feels. You have initial, quick intuitions about the person—calling on your database of gut feelings, stereotypes, and subliminal perceptions—which are followed seconds, hours, or years later by slower, more reasoned judgments. We now know that when you make fast decisions, your frontal insula and anterior cingulate are active. These areas are also active when you experience pain, fear, nausea, or many social emotions. When you think something is funny, these same cells fire up, probably to recalibrate your intuitive judgments in changing situations. Humor serves to resolve uncertainty, relieve tension, engender trust, and promote social bonds.

It is believed that the rapid communication system involving the VENs may have evolved in mammals living in complex social organizations, enabling them to rapidly respond and adjust to quickly changing social situations through gut-based decision making. Because of their proposed role in social behavior, intuition, and empathy, it has been suggested that VEN abnormalities may contribute to the pathophysiology of autism spectrum disorders, including the compromised ability of these patients to empathize and interact socially. Although there’s currently no direct scientific evidence to support this speculation, it’s conceivable that the development of the VEN system in the brain is related to altered composition and function of the gut microbiota during the first few years in life, including the signals they send to the brain. Altered gut-brain communications have long been implicated in some forms of autism, and recent experiments using a mouse model of autism have identified altered gut microbe-to-brain signaling as a possible mechanism underlying these animals’ autism-like behaviors.

DO ANIMALS HAVE GUT FEELINGS?

As humans, we take for granted our social emotions such as embarrassment, guilt, shame, and pride, and assume that animals, especially those we live with, must share the same feelings. Dog lovers swear that their canine companions experience emotions like shame, jealousy, anger, and affection in the same way we do.

However, if we go strictly by the anatomy of the brain, animals do not have the capacity to experience these emotions; their brains just aren’t wired that way. The self-awareness of emotion conferred on humans by the anterior insula and its interactions with other cortical brain regions, in particular the prefrontal cortex, is unique. Dogs do have insulas but their frontal aspects are rudimentary. Internally generated sensations, including those from the gut, are integrated in the base of their brains and in subcortical emotional centers, rather than in the frontal insula. Dogs and other pets are clearly emotional but not self-aware, so no matter how human their emotional expressions appear, they are not in the same league with you, not matter how hard this is to accept.

Building Your Personal Google

Imagine that our memories of emotional moments are stored in our brains as tiny YouTube video clips. These videos contain not only the visuals of any given moment, but also the associated emotional, physical, attentional, and motivational components. We rarely remember the dates or specific circumstances of such events. Billions of these clips, or “somatic markers,” are held in the biological equivalent of miniaturized servers in our brain and “annotated” (linked) with motivational states: a negative marker is associated with an unpleasant feeling and with the motivational drive of avoidance, whereas a positive marker is associated with a feeling of well-being and a motivational behavior to seek it out.

When we make a decision based on our gut feelings, the brain accesses the vast video library of emotional moments in our brains, like a Google search. In other words, you don’t have to go through the time-consuming process of consciously considering all the possible positive and negative consequences of every particular decision you make. When faced with the need for action, your brain predicts how a given response will make you feel, based on its emotional memories of what took place when you were confronted with other, similar situations throughout your life. This probabilistic process then guides you away from responses that are likely to make you feel bad—that is, anxious, pained, sick, sad, and so on—and toward responses that are linked to memories of feeling comfortable, happy, cared for, etc. Besides allowing you to make decisions more quickly, this mechanism lets you benefit from the past lessons without the psychological burden of reliving them. If you were to constantly revisit and relive your painful and unpleasant experiences, you’d go insane.

WOMEN’S INTUITION

In my experience with patients, many women seem to be better at listening to their gut feelings and making intuitive decisions than men are. The growing interest in identifying sex-related differences in emotional processing and in the prevalence of chronic pain conditions led to a series of studies funded by the National Institutes of Health aimed at identifying sex-related differences in brain responses to painful and emotional stimuli.

For a variety of political and convenience reasons, the study of such biological differences between women and men has been largely neglected, as it is automatically assumed that the female brain responds to such stimuli, as well as to medications, in the same way as the male brain. However, research by our group and others suggests that women tend to show greater sensitivity to the brain’s salience and emotional arousal systems attuned to physical feelings like abdominal pain and emotional feelings like sadness or fear, than men do. One explanation of these differences may have to do with the fact that women store memories of physiologically painful or uncomfortable states such as menstruation, pregnancy, and childbirth. When expecting a potentially painful experience, the female brain has a more extensive somatic marker library to go by, and its salience system may have greater input from such memories than the male system.

Are Decisions Based on Our Gut Feelings Always Right?

If what we know or reasonably suspect about gut feelings is true, then shouldn’t gut-feeling-based decisions be the best decisions?

Yes and no. While gut feelings are more informed by our own experiences and learned knowledge than we may have ever considered, they are also easily corrupted by a variety of outside influences, including traumatic experiences, mood disorders, and advertising messages.

For example, TV programming is full of commercials targeted directly at your gut feelings, whether the aim is to motivate you to eat a hamburger, go on a diet, or take a medication. These cleverly designed commercials capture your attention by presenting images, including an implicit promise of reward, that are embedded smoothly and effortlessly into your stored library of gut feelings and experiences.

Take, for example, the advertising slogan for a brand of peanut butter that says, “Choosy moms choose Jif.” Being choosy with regard to your children’s health is a gut feeling that most parents have; it’s laudable. Advertisers and other influences can hijack such basic gut feelings by taking advantage of the fact that you’re busy. You may consolidate and simplify information. Your gut-based desire to “be choosy when feeding your children” combines with the slogan “choosy moms choose Jif” in your brain to form the imperative “choose Jif,” which is then mistaken for a gut feeling. So the question becomes not whether you can trust your gut feelings, but how you can learn to accurately identify what your true gut feelings are. Although the circuitry for making instantaneous gut-based, intuitive decisions evolved to enable you to live and navigate in complex societies, your challenge today is to use your gut to understand what is meaningful to you.

Our ability to make gut-feeling-based predictions and decisions is a by-product of evolution; in a dangerous world filled with life-threatening situations, a systemic bias toward assuming a high likelihood of bad outcomes can provide a significant survival advantage. Today, however, such a system has become maladaptive in most parts of the developed world, where life-threatening physical threats have largely been replaced by daily psychological stressors—the result being that our negatively biased gut-based decisions now result primarily in unhappiness and negative health outcomes.

A good example of this is the story of Frank. He had to force himself to go to lunch meetings with his clients, because his brain’s predictions regarding what would happen in an unfamiliar restaurant created so much anxiety and related gastrointestinal symptoms that he was unable to focus on the meeting. This phenomenon is known as catastrophizing, which simply means that your brain makes the (wrong) gut-feeling-based prediction that the worst possible outcome (in this case, severe digestive symptoms) will occur. The instant Frank found out about a new appointment, his intuitive, negatively biased prediction of future events in the restaurant kicked in, preventing him from rationally assessing the situation. Catastrophizing is also a common trait in patients suffering from depression or chronic pain, whose attention is narrowed to only negative stimuli. Some people with these conditions have completely lost the ability to make gut-feeling-based decisions that are good for their well-being.

HOW WE DECIDE

When it comes to buying a bottle of wine, there are three types of strategies, depending on your decision-making strategy.

First are the linear, rational types who base their decision on what they have learned in a wine-tasting class (the best years for that particular varietal, the amount of sugar added, the age, and so on) or from reading the newsletter published by a famous wine master. Gut sensation experts, on the other hand, make their decisions based on a natural or trained ability to detect an astonishing number of different flavors and aromas (ranging from chocolate to raspberry to cinnamon) when smelling and tasting a particular wine. Finally, there are the intuitive types, the gut feeling experts, who over their lifetime have accumulated a vast library of emotional memories related to wine consumption. These memories may include enjoyable moments experienced in a small town in Tuscany or Provence, or drinking a simple bottle of red wine with delicious food in the company of good friends. Memories may also include the fragrance of the surrounding lavender fields and the thunderstorm that drove everybody from the outdoor restaurant inside. The gut feelings generated and stored during these pleasant experiences contain not only the actual taste of the wine (the gut sensation), but also the context (beautiful scenery) and the feeling state (being relaxed, happy, or in love).

When you watch the three types making a decision about which wine to buy, the rational type will do searches on the Internet and carefully, logically weigh the price, year, and other learned information about the wine. The sensory experts may go to a wine-tasting room to discover the ultimate blend of flavors and aromas. Meanwhile, the intuitive type will be influenced primarily by the memories they may have about the particular part of the world where the wine originated, or about the occasion at which they shared the wine in good company.

Accessing Your Gut Feelings Through Dreams

If we were able to watch a gut-feeling-based documentary of our lives, composed of all these individual clips spliced together, we would presumably witness a fascinating, highly personal biopic, played out in vivid colors.

But short of such a fantasy, how might we catch a glimpse of the video library in our minds? Watching our own emotional biopic during waking hours, when we’re busy dealing with the challenging world around us, would be incredibly distracting. A much more plausible time to view such a movie would be at night, when we are not distracted by work, family, or friends, and when our body is temporarily offline and won’t move during even the scariest scenes. And in fact, that’s exactly when showtime occurs for this cinema of the emotions—when we are asleep, or, more specifically, when we are absorbed in our dreams.

The experience of dreaming can often seem as if we are actually watching a movie, and anybody who is able to remember his or her dreams will agree that the human brain is a remarkable film director. It is generally assumed that the most vivid dreams occur during the period of sleep called rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. During REM sleep, your breathing becomes more rapid, irregular, and shallow, your eyes jerk rapidly in various directions, and your brain becomes extremely active. Movies of particular personal relevance play more frequently, and appear in more colorful and emotional formats.

Brain imaging studies in sleeping subjects demonstrated that the brain regions activated during REM sleep include the familiar salience network regions of the insula and cingulate cortex, along with several emotion-generating regions—including the amygdala, and regions involved in memory, such as the hippocampus and the orbitofrontal cortex—as well as the brain region essential for experiencing the images, the visual cortex. At the same time, brain areas involved in cognitive control and conscious awareness, including the prefrontal and parietal cortexes, and regions controlling voluntary movement are turned off. You are paralyzed. This way, we can experience an uncensored version of our film without worrying that we’ll fall out of bed when we feel like running away or punching someone in the face. You cannot enact your dreams, unless you have a rare sleep disorder.

Interestingly, while our body movements are turned off, the brain-gut-microbiota axis is more active during sleep than at any other time. The migrating motor complex—the powerful contractions and bursts of gastrointestinal secretions, discussed in Chapter 2, that pass through our intestines every ninety minutes when there is no food in our gastrointestinal tract—are fully activated during sleep, and dramatically change the environment for our gut microbes (and presumably their metabolic activity) during this period. Based on what we know today, it is likely that these contractile waves are also associated with release of the many signaling molecules in the gut and with transmission of this information to the brain, via the many gut-to-brain communication channels. Even though no scientific studies have been done to prove this point, I wouldn’t be surprised if such bursts of intense gut- and microbe-to-brain signaling, with all the neuroactive substances being released during this process, play a role in the affective coloring of our dreams.

Why is dreaming significant? One proposed theory is that dreaming during REM sleep helps to integrate and consolidate various aspects of our emotional memories. As I’ll discuss later, dream analysis is one way to get in touch with and learn to trust your gut feelings. While there are many other hypotheses about the role and importance of dreams, the idea that one of its functions is to consolidate the emotional memories in the form of gut feelings that we accumulated during the day fits much of the scientific data that has been gathered in this field. Some intriguing recent findings, for example, suggest that the gut-brain axis, possibly including signals from the microbiota, plays an important role in the modulation of REM sleep and dream states. So the next time you have a late meal just before going to bed, or get up in the middle of the night to forage in your refrigerator, you might think about the unintended effect this may have on your nighttime movie showing, and the updating of your internal database!

A quarter-century ago, at a time when I was overwhelmed by decisions I had to make about my own life’s direction, I was fortunate to have gone through Jungian psychoanalysis for several years. Carl Gustav Jung was a famous psychiatrist at the Burghölzli psychiatric hospital in Zurich, Switzerland, and a contemporary of Sigmund Freud. He was the founder of analytical psychology, an elaborate conceptualization of psychology that includes such key concepts as a shared (collective) unconscious; universal, inborn patterns of unconscious images (so-called archetypes) that guide our behavior; and the concept of individuation, a psychological process of integrating opposite psychological tendencies, like introversion and extroversion. Jung saw dream analysis as the key strategy to get access to our unconscious. Today I speculate that the latter process has a lot to do with getting in touch with, and learning to trust, your gut feelings.

While I had always been fascinated by Jung’s writings about dream analyses, I wasn’t quite ready for the recurrent weekly questions from my therapist regarding the dreams I’d had since our last appointment. While I had begun my therapy looking for practical help on making the most rational decisions about my future, my therapist consistently redirected me to look inside myself and find the answers from my dreams.

There were weeks when I was terrified, driving to my weekly appointment without a single dream written down in my journal, facing a session where there would be nothing to talk about. Over a matter of months, however, the dreams I was able to remember steadily increased in their frequency, detail, and intensity. I was amazed at the beauty, story lines, and complexity of the “inner movies” that I was watching every night. The most elaborate of these dreams, associated with the strongest feelings, turned out to be the ones with the greatest personal meaning. The combination of writing down my dreams every morning and then reflecting on them, with or without my therapist, gradually brought me to a point where I was able to connect with my internal database of emotional memories, and began trusting my inner wisdom reflected in these dreams more and more in making important decisions, rather than relying on the advice of friends and colleagues.

But dream analysis is not the only way to get in touch with your gut feelings. There are other ways of training yourself to listen to your gut feelings that are less cumbersome and expensive than Jungian psychoanalysis. Ericksonian hypnosis is one. Milton Erickson, a famous hypnotherapist, was a master at putting his patients into a trance by directing his elaborate, hypnosis-inducing stories alternatively to the conscious, rational (left) side of the brain and to the wise, all-knowing unconscious (right) side of the brain. Over the course of the hypnotic induction, the subject would come to trust the unconscious side more and more, while letting go of any attempt to control things through rational, linear thought mechanisms. Not only is hypnosis a highly effective way of rapidly switching the brain from an external attentional focus to an introspective mode, thereby inducing a trance, but repeated sessions of Ericksonian hypnosis also change the way patients make important decisions when they are not in a trance state. Over time, many of Erickson’s regular subjects increasingly learned to trust this inner wisdom and make their decisions accordingly.

The Bottom Line

We use the expression “gut feeling” frequently in our daily conversations, without realizing that a tremendous amount of cumulative scientific evidence provides the biological underpinnings for this term. The quality, accuracy, and underlying biases of this gut-brain dialogue vary between different individuals. Some gut sensations are recorded with high fidelity and are replayed in a subliminal way: Even though they rarely reach our consciousness, such movies, like dreams, are likely to play an important role in our background feeling states. In addition, certain individuals seem to be more sensitive and aware of all signals coming from the gut. They may view themselves as always having had a “sensitive stomach” or may have been told by their mothers that they were colicky babies. Some learn to live with this hypersensitivity and accept it as part of their personality. They will tell you that they are more sensitive to food and medications and will feel butterflies in their stomach when anxious. Others in this group develop common gastrointestinal disorders such as IBS, as their brain, flooded by a constant stream of aberrant signals from the gut, generates inappropriate gut reactions based on the signals received.

By getting in touch with our gut feelings, understanding the role that our personal collection of gut-based memories plays in our intuitive decision making, and keeping in mind that whatever we do to influence the activities of our gut microbes—through our diet or medication intake—may also influence our emotions and predictions about the future, we can fully tap into the vast potential of the gut-microbiota-brain axis.

It seems strange that given the crucial importance of gut-based decision making, there is no formal mechanism in place to train and optimize this remarkable ability. We certainly don’t learn about it in school, and many parents don’t tell their children to listen to their gut, instead stressing the importance of thinking things through logically (which, of course, is also a valuable skill for impulsive adolescents to practice). The ultimate dogma of modern society is to make rational decisions based on the assumption that the world is linear and predictable, and that if you have enough information about the world, you can make the best decisions. I strongly believe that once we gain a better understanding of the biological underpinnings of intuitive decision making and accept it as a worthwhile goal to invest our mental energies in improving these skills, there is a range of strategies we can embark on to improve our ability and inclination for gut-feeling-based decision making later in life.