THE STORM BEGAN SMALL, CHEWING ITS way across Florida like a teething baby, then, suddenly broad-shouldered and bullying, as big as the Gulf, it came howling at a stretch of the Mississippi and Louisiana coast with a storm surge twenty-eight feet high, sweeping away homes that ocean had never before touched.

More than a decade after Katrina—no one on the Gulf Coast says “Hurricane Katrina,” it’s just “Katrina”—people here use it as a reference point. There is before the storm and after the storm. In Mississippi rebuilding was simpler—not easier, just simpler. Everything was gone. Few had to decide whether to restore or tear down because there was nothing left to tear down. And there were resources. Mississippi’s governor, Haley Barbour, the plugged-in former Republican National Committee chairman, got Mississippi far more than its share of federal dollars, enough so that places like Starkville, two hundred miles from the coast, got $8 million to build a parking garage, and nearly a decade after the storm $872 million remained unspent.

New Orleans was where the complexity—and much of the horror—was. Katrina killed 1,833 people, 1,577 of them in New Orleans. And betrayal began before the storm. Most of the city flooded from the rear, from Lake Pontchartrain, where storm surge was much lower than on the coast—not high enough to overtop flood walls the Army Corps of Engineers had built. Yet those same flood walls—some completed only five years before Katrina—collapsed because of poor design. Later, the Corps itself conceded it had provided flood protection “in name only.”

The horror came with the chaos, the political gamesmanship, the extraordinary incompetence of the Federal Emergency Management Agency—for example, holding search-and-rescue teams in Atlanta to hear lectures on sexual harassment instead of letting them save lives—and the ensuing breakdown of order. City government was worse. Mayor Ray Nagin gave incompetence a bad name: while cutting illegal deals unrelated to Katrina that sent him to jail in 2014, he took almost a year and a half to name a rebuilding “czar,” who two years later, after accomplishing exactly nothing, was laughed out of town.

Yet New Orleans did recover. Ten years after the storm, it had far exceeded the most optimistic predictions for its recovery. There are two reasons for this.

First, it’s New Orleans. No other city in the country has so identifiable a culture, a culture that emanated from the city’s intricate histories and made it a prime world tourist destination, a culture that, combined with a lack of economic opportunity over many decades, also made it the country’s major city with the highest percentage of people living there who had been born there. Though the city may have been insular, its citizens loved it, and fought for their home. They had to. As Harry Shearer said, “The illusion of leadership is much more dangerous than no leadership. We had no illusion of leadership.” So people did things themselves, rebuilt homes and neighborhoods themselves. And grassroots leadership defined what happened, and to hell with planners.

Second, plenty of outside help arrived. Tens of thousands of volunteers and tens of billions of dollars came; young people in their twenties came. Before the storm, those few who moved to New Orleans had sought to fit into what was. These new immigrants, invigorated by possibility and entrepreneurial spirit, were determined to make space for themselves. Suddenly trendy, in 2013 New Orleans became the nation’s most popular destination for working-age Americans; in 2014, it led the nation in growth in college graduates. They changed the city, made it greener, more dynamic, more sophisticated; typically, one neighborhood restaurant removed shrimp, crab, and crawfish from its menu, replacing them with such items as oxtail soup. And neighborhoods changed.

Indeed, two parallel universes developed. Gentrification had moved slowly in New Orleans, creating mixed neighborhoods; now, suddenly, it accelerated, pushing the black community out of its neighborhoods. If for whites New Orleans is doing better than it has in decades, African Americans have yet to find enough places for themselves.

And for both communities, there’s one great overhang: the threat of the next storm and the dissolution of coastal Louisiana. The state has lost roughly two thousand square miles of land—equivalent to the state of Delaware—since 1932. Chief causes are levees, which prevent a flooding river from depositing sediment, and the oil and gas industry, which dredged thousands of miles of canals. That land once provided a protective buffer to absorb hurricane storm surge. Land loss continues, and sea level rise is coming. The state has a plan, but no money to fund it. The city has a new levee system—one that will perform as designed this time. But will these things protect the city into the future, or is New Orleans the next Atlantis?

(1956–)

A SONGWRITER’S SONGWRITER, ROBERT EARL Keen, Jr. is Texas through and through. Raised in Houston and steeped in the work of fellow Texans Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark, Keen—along with his best pal and fellow A&M Aggie, Lyle Lovett—has made his name by writing literary, sweeping songs full of rich Lone Star characters. Over the course of nearly thirty years and twelve studio albums, he’s become one of the preeminent alt-country artists, staying firmly outside of the Nashville machine while garnering plaudits from everyone from George Strait to Dave Matthews. His live chops are unquestionable, honed by playing the Texas dance-hall circuit, with his amiable storytelling and sizzling backing band captured not once, but twice at the legendary Gruene Hall for 1996’s No. 2 Live Dinner and the 2016 sequel, Live Dinner Reunion.

A RACETRACK AS WELL AS A THOROUGHBRED auction house, Lexington, Kentucky’s Keeneland lies in the red-hot center of what’s called the Inner Bluegrass, a stretch of God’s country where the flinty, limestone-tinged water yields smooth-strong racehorses and smooth-strong whiskey. The greatest Thoroughbred-breeding farms in the world—Calumet, Lane’s End, Claiborne, Gainesway, among others—are within a stone’s throw of town, and during Keeneland’s famed September Yearling Sale, the private jets stack like sardines out at Lexington International. Over the years, the September sale and Keeneland’s two other annual auctions have produced twenty-one Kentucky Derby winners, twenty-three Preakness winners, and nineteen Belmont Stakes winners, not to mention the ninety-five horses that have won, more than a hundred Breeders’ Cup series races. The track’s spring and fall meets certainly hold their own, too, providing the stages for eleven Grade I stakes races.

Keeneland came to be in 1936, after a group of Bluegrass horsemen purchased the property from Jack Keene—whose breeding farm upon which the track and sales barns were built had been in family hands for more than a century—to construct the world’s first racetrack with a strong sales component. Globally renowned for a half century, a national landmark since 1986, and relatively unchanged since its founding, Keeneland remains extraordinarily beautiful and thus served as a set for the film Seabiscuit. It is that rare, organic thing among sporting institutions: it had to occur where the horses were born, in this precise limestone-fed chunk of their Kentucky home, and nowhere else.

EACH MAY, AS MILLINERS ACROSS AMERICA and around the globe sweat bullets over the last little insouciant flicks and upturns of their fascinators, it behooves us to remember that the roots of all Kentucky Derby madness lie in the towering equine passions of a prescient Southern madman, Meriwether Lewis Clark Jr. A Kentuckian and horseman of distinction, Clark was the grandson of the explorer William Clark (yes, of that Lewis and Clark). In 1872, he succumbed to his familial DNA for travel and struck out for Europe. His notion was to take in the great European horse races—first at Epsom Downs for the Derby, which had been run since 1780, and then at Longchamps, where the French Jockey Club had organized the Grand Prix de Paris just ten years earlier.

Lit up by these great races and the culture surrounding them, Clark returned to Louisville in 1873 to devote himself to bringing events of similar magnitude to Kentucky. His social reach spanned the young continent, which is another way of saying, as a descendant of one of the first families of Kentucky—his mother was a Churchill—and since he belonged to American royalty as a Clark, he had what the Bluegrass horse breeders would today call the right pedigree to arrange a fine horse race.

It didn’t take him long upon his return from Europe to do that. He quickly formed the Louisville Jockey Club and leased the hundred acres for what became Churchill Downs from his uncle John Churchill (hence the name of the track). A scant two years after his return, in 1875, Clark produced the very first Kentucky Derby, with a fifteen-horse field. In a moment of pure athletic and political poetry, America’s first Derby, run at a brutal mile and a half, was won by Aristides, who was exquisitely trained by the subsequent Hall of Fame trainer Ansel Williamson, one of the rare African American trainers in the fledgling industry. Aristides was ridden to his win by the star jockey Oliver Lewis, also African American. In other words, a short ten years after the cessation of hostilities of the Civil War, two superbly talented African Americans won America’s premier race at America’s premier track.

For his part, Clark, a man of ferociously short temper and enormous competitive drive, did not let the Derby’s spectacular beginning be the end of the story. Year after year, he roped in the owners who brought the horses. As with so much in Clark’s turbulent life, what follows may be legend, or it may be fact, but according to the legend, at a post-Derby party in 1883 hosted by the so-called King of the Dudes, Evander Berry Wall, an extravagant New York socialite and a founding father of the Belle Époque’s café society, Clark noted well that Wall handed out roses to every woman he had invited to the party. What is indisputably in the historical record is this: by 1896, the famous garland of several hundred roses was being tossed over the winner of the race.

Since then, the race has grown to occupy its pride of place in what by 1930 had become the Triple Crown. As the big inaugural race for three-year-olds, the Derby has become the debut for a global crop of superb young athletes at the beginnings of their careers. The names of the winners alone are a record of the sport’s last 142 years, from 1930’s Triple Crown winner, Gallant Fox, to Secretariat, who still holds the track record from his Derby win in 1973, to 1978 Triple Crown winner Seattle Slew, and on up to 2015’s American Pharoah.

The Derby is the big, bold, ripping renewal of an athletic season and brings us the flower of youth, who contest in it with furious grace. In this, at bottom, Meriwether Clark’s race has become the Southern stage for a national rite of spring.

SMALL, TART KEY LIMES MADE THEIR WAY across the Atlantic with the Spanish conquistadores, and groves were already well established in the Florida Keys by the end of the Civil War. Around the same time, condensed milk became a pantry staple and a welcome source of shelf-stable dairy. The eureka moment didn’t take long. Before the turn of the century, locals were combining the puckery juice with the milk and some beaten egg in a crumb crust. A hurricane wiped out most of the groves in the 1920s, killing the trees if not the recipe. For decades, key lime pie was made with the larger, ubiquitous Persian limes or bottled, pasteurized juice, cases of which line the pantry of any coastal seafood shack. Fresh key limes are now available year-round, though they spoil quickly. So when you get ahold of some, have your pie (and perhaps daiquiri) ingredients ready.

PITY THOSE WHO ONLY SEE THE SOUTHERNMOST point of the continental United States after spilling off the gangway of a cruise ship onto the main drag to do the Duval Crawl for piña coladas or catch the daily Sunset Celebration at Mallory Square. Small as Key West is—an easily biked or walked four miles across by one mile wide, with just 25,000 or so residents—this island deserves more than the few hours afforded the 800,000-plus passengers who disembark every year to sample the original Margaritaville.

Key West owes much of its import to its “end of the earth” location—the terminus of the Florida Keys, where the shipping lane known as the Straits of Florida and the Gulf of Mexico meet the Atlantic, ninety miles this side of Cuba. Once inhabited by indigenous Calusa people, the island was first “discovered” by Juan Ponce de León in 1521 and settled by Spaniards, who christened it Cayo Hueso (“bone cay”). It changed hands several more times before the United States planted its flag in 1822. Trade ships and pirates swarmed, often getting trapped in the coast’s expansive coral reef, and shipwreck salvage became a leading industry (visit the Mel Fisher Maritime Museum to see some of the booty). When the Civil War began, the Union retained control of Key West thanks to the recent construction of Fort Zachary Taylor, one of several military outposts (and namesake of a state park that today offers beach access—the real southernmost point open to the public, no matter what that giant buoy monument at the corner of South and Whitehead Streets claims). Thanks to salvaging and the cigar industry, by the mid-1800s the city of Key West ranked, per capita, as one of the richest in the country.

Walking around, you’ll most likely see flags heralding the island as the Conch Republic, so-called by locals in 1982 when the city announced its “secession” from the States after a tourism-hampering roadblock aimed at foiling drug smugglers in the Upper Keys. Other island hallmarks include tours of Hemingway’s French Colonial home, where the author lived from 1931 to 1939, complete with his standing desk and descendants of his mysterious six-toed cats. A lookalike contest devoted to Papa every July at his favorite bar, Sloppy Joe’s. Harry S. Truman’s “Little White House,” where the president spent 175 days of his terms in office. The zero mile marker of U.S. Highway 1. Rainbow flags. Chipped beef on toast at Pepe’s Café. Sportfishing for sailfish, tarpon, and permit, among other species. Sunbathers at Smathers Beach. Quaint B&Bs with rocking chairs on porches in genteel Old Town. Loose roosters in the streets. Key lime pie at Blue Heaven. Key lime pie everywhere.

TENDER SPRING GREENS CAN’T STAND UP TO hot bacon fat. They wilt—get “kil’t”—under the dressing of bacon, onion, and vinegar that makes this traditional Appalachian dish. See Greens.

(1925–2015)

HE SOMETIMES SEEMED TO BE LISTENING TO Lucille, his guitar, as if translating her emotions rather than his. Born Riley B. King, B. B. King was perhaps the last of the great bluesmen, the self-created ones who rose from sharecropping in Mississippi to worldwide acclaim. Playing in town for tips on Saturday afternoons, he soon found that gospel songs elicited compliments, while the blues got money and beer. “Now you know why I’m a blues singer,” he told an interviewer.

He blended the blues with gospel and country. By 1970, with his hit “The Thrill Is Gone,” he’d become an idol to legions of long-haired rockers: Eric Clapton, Billy Gibbons, Jimi Hendrix, Duane Allman, and countless others. His licks, phrasing, and facility for bending notes were singular. But it was his inimitable vibrato—stinging, vibrant, alive—that made it possible to hear two notes and instantly know who was playing. He could tear your head off with his guitar or voice, as Bono learned at close range while recording U2’s 1988 duet with King, “When Love Comes to Town.” Bono recalled how he’d given the song’s opening howl everything he had. “And then B. B. King opened up his mouth and I felt like a girl.” Who didn’t? No serious rocker even tried to compete with him.

What King is less credited for is just as important: his subtlety, restraint, what he didn’t play. It made what he did play that much more meaningful. The guitarist Derek Trucks said King’s playing “was just the cold hard truth—like hearing Martin Luther King speak. You just needed one word, one note with B. B. No one has that.”

(1927–2006)

“OFTEN, I AM MADE TO SOUND LIKE AN ATTACHMENT to a vacuum cleaner: the wife of Martin, then the widow of Martin, all of which I was proud to be,” Coretta Scott King told her friend Barbara Reynolds, a writer and minister. “But I was never just a wife, nor a widow.” A civil rights fighter who boycotted, marched, and spoke out for social justice, King devoted much of her adult life to Atlanta’s Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, which she founded to promote her late husband’s philosophy of peace and methods of resistance. Born in Marion, Alabama, in 1927, Coretta Scott won a scholarship to the New England Conservatory of Music, where she trained to become a classical singer. A mutual friend set up her first date with Martin Luther King; the two married in 1953 and moved to Montgomery, where violent threats by racist whites loomed over their home. Coretta Scott King realized just how much she was willing to sacrifice for the movement when in 1956 a man threw a bomb through their front window. She called on that courage decades later when she was arrested for protesting apartheid, and when she denounced homophobia, a stance that many black pastors then rejected.

(1929–1968)

FROM 1955 UNTIL HIS ASSASSINATION IN 1968, the most prominent and widely known leader of the American civil rights era, the struggle to attain legal equality and economic justice for African Americans; an Atlanta-born Baptist pastor and president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; spokesman for the 1955 Birmingham, Alabama, bus boycott that led to the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling racial segregation on transportation unconstitutional, and leader of the 1963 campaign in Birmingham, the televised images of which—showing police responding to demonstrations with fire hoses and attack dogs—helped prompt landmark federal civil rights laws; acclaimed orator of the “I Have a Dream” speech during the 1963 March on Washington; winner, at age thirty-five, of the Nobel Peace Prize; and, as his biography at Atlanta’s Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change (an archive and memorial to his legacy) concisely summarizes, “one of the greatest nonviolent leaders in world history.” “King was trying to tell the nation something it didn’t want to hear,” the journalist Taylor Branch (who spent more than two decades researching and writing the three-volume history America in the King Years) told Smithsonian Magazine in 2015, “that we can’t put race on the back burner. That race isn’t just a Southern problem or a problem of segregation, it’s an American problem at the heart of American history and the measure of American democracy.” See Lorraine Motel.

INSIDE A SMALL STUDIO IN DOWNTOWN Helena, Arkansas, just across the Mississippi River from the crossroads where Robert Johnson may or may not have sold his soul to the devil, DJ Sunshine Sonny Payne just said, “Pass the biscuits, cause it’s King Biscuit Time!” It’s what he says at the start of every King Biscuit Time radio show, which just aired its 17,737th episode. Who knows how many more will have run by the time you read this, but you could tally it up: one show for every day of the workweek since the show’s debut on November 21, 1941, making this blues program the longest running daily radio show in America. Named for King Biscuit flour, a local brand that provided the original financing, King Biscuit Time airs on KFFA, which in 1941 was the only station in the area to broadcast music by African Americans; the show took on its unusual 12:15 p.m. time slot to coincide with the lunch hour of black laborers in the Delta. (Nowadays listeners outside the station’s range can stream or download episodes on kffa.com.) Members of the original live band included Sonny Boy Williamson and Pinetop Perkins, and the show’s influence has been profound, shaping the early musical tastes of such icons as B. B. King, Levon Helm, and Ike Turner.

NEW ORLEANIANS CAN COME TO BLOWS OVER which neighborhood bakery—Gambino’s, Randazzo’s, Dong Phuong’s—makes the tastiest king cake, but the truth is that the cherished confection is little more than a gaudily iced coffee cake. Hardwired tradition and ritual—that’s what really prods the Crescent City to devour 750,000 of them each year. Cakes containing a hidden prize actually may predate Christianity; by the late nineteenth century, Mardi Gras krewes used them to pick who would preside over the next pre-Lenten soiree. (Lore also holds that an early Mardi Gras king established the cake’s purple, green, and gold color scheme to denote justice, faith, and power.) Along the way the coin hidden inside gave way to a tiny baby figurine, and the “reward” for finding the tot in your slice (hopefully without cracking a molar) became the obligation to purchase the next cake. Hence the perpetual supply of king cake in every employee break room in New Orleans during Mardi Gras season—and the reason that giving up dessert is the go-to choice of Lenten penance.

KOLACHES ARRIVED IN TEXAS ABOUT A CENTURY before Interstate 35, but it’s the highway that helped make the yeasty pastry famous. Traveling Texans know to stop in West, about halfway between Austin and Dallas, for its bakeries’ interpretations of the Czech sweet—although which bakery makes kolaches best remains a matter of fierce debate. Closely related to Danish, hamantaschen, and other filled pastries with old-world heritage, kolaches arrived in central Texas in the 1850s with immigrants drawn by the promise of cheap land. Soft and puffy, kolaches are typically filled with apricot, prune, poppy seeds, or sweetened farmer cheese, and if they’re not hot when you buy them, most kolache bakers will point you toward the microwave. Beyond West, kolaches are sold at gas stations, doughnut shops, and groceries all over Texas, alongside tightly wrapped meat rolls that are classified as kolaches, too. Technically, the sausage version is a klobasnek, but as long as there’s not a Czech speaker within earshot, it’s fine to ask for a sausage kolache. Heck, ask for two.

KOOL-AID PICKLES—A TYPICAL RECIPE MIXES four packets of cherry-flavored Kool-Aid with two cups of sugar and a jar of whole dill pickles—originated in kitchens and corner stores of the Mississippi Delta as a quick and cheap method for a sweet-and-sour snack. But they’ve since surfaced everywhere from Dallas to the Carolinas, including even fancy restaurants that are experimenting with the form. Eat carefully, lest you end up with electric-red fingers.

AS THE STORY GOES, A PACK OF CAMELS, made in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, inspired Vernon Rudolph to seek his destiny in the city where he would go on to launch an empire. Armed with a yeast doughnut recipe procured from a New Orleans chef, the Marshall County, Kentucky, native set up what was initially a wholesale operation in 1937. But it wasn’t long before he cut a hole in the side of the building to sell doughnuts directly to people drawn to the bakery by their noses. Southerners have been lining up ever since, and so has the rest of the world: today Krispy Kreme has more than a thousand locations as far afield as Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia, and Singapore, the smell of those featherlight rounds a persistent come-on for millions who insist that the only doughnuts worth the calories are hot and fresh.

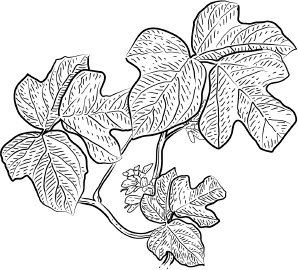

PUERARIA LOBATA: THE VINE FROM HELL, the plant that ate the South. Kudzu was introduced at the Japanese pavilion of the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, for livestock feed and erosion control. It looked real good on paper: kudzu grows in all kinds of dirt, even gummy red clay. A legume like peanuts and clover, it has deep roots that add organic tilth to the soil, hosting bacteria that put nitrogen back in the ground. Starting in 1935, the U.S. government’s Soil Conservation Service paid farmers as much as eight bucks an acre to plant it.

Fast growing, propagating by root, seed, and tendril, kudzu has since become the South’s most noxious weed, taking over (by some estimates) eight million acres in the last century. Grazed, mowed, and sprayed to scant effect, it spreads across 200,000 new acres annually. It was declared a Federal Noxious Weed in 1998—too late. Entire stands of pine succumbed to kudzu’s smothering embrace, as did power lines, phone lines, railroad lines, abandoned farmhouses, entire run-down small farm towns. Goats love kudzu, but, alas, there just weren’t enough goats. Giraffes would have helped, but there were none.

During summer, kudzu can grow as much as a foot a day. Doze off on the front porch too long and a kudzu vine will lash you to your rocking chair. True? Almost.