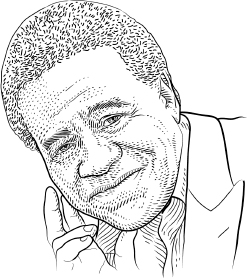

(1933–)

AS A CHILD IN RURAL POINTE COUPEE Parish, Louisiana, Ernest Gaines picked cotton and fished the bayous on the same plantation where five generations of his family had been born and raised before. There was no high school for black children in that parish, though, and so at fifteen Gaines moved to California. There he spent hours absorbing books in the Vallejo public library, and because he lived across the bay from the infamous San Quentin State Prison, he developed a fascination with the idea of death row. Gaines found success writing and publishing fiction over the years, but it was that lingering interest in capital punishment that eventually helped form the novel for which he is best known: A Lesson Before Dying (1993). The story of a young black man railroaded into a murder conviction in rural Louisiana and sentenced to death for it won the National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction and brought Gaines wide acclaim. Now living on the same plantation where he was born, Gaines has said the most important moves in his life were “the day I went to California and the day I came back.”

WHILE YOUNGSTERS ELSEWHERE MARVEL AT pictures of dinosaurs in books, children in the Deep South dodge them on the way to school. Alligator mississippiensis has made itself comfortable in the wetlands of what became the Southeast United States since the Jurassic period, surviving three mass extinctions and at least eight seasons of Swamp People. That other top threat, Homo sapiens, converted nearly the entire species into luggage in the 1950s, but protections have allowed populations to rebound—gators now flourish in Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, and even Oklahoma. Stealthy predators of everything from minnows to deer, they can grow to a whopping thirteen feet long and eight hundred pounds, and they don’t always confine themselves to remote swamps. As human habitat continues to encroach on their domain, close encounters of the reptile kind become more and more common. Granted, it may be inconvenient (and hair-raising) to stumble across a gator on a putting green or in a backyard swimming pool, but just remember—they were here waaaay before us.

ORIGINALLY PIECED TOGETHER FROM THE scraps of old work clothes, overalls, dresses, feed sacks, and other fabric remnants marked by stains reflecting hardscrabble life in the rural South, these one-of-a-kind textiles are abstract works of modern art. Gee’s Bend quilts stand apart for their simple yet vibrant patterns, reminiscent of Amish quilts but with an improvisational flair. That the rural African American community tucked into a bend in the Alabama River has produced five (and in some families six) generations of enviably talented quilt artists is due in large part to their isolation, which helped foster a unique artistic voice—each maker’s design reflecting both her singular experience and that of her community as a whole. Even the notoriously snooty New York City art crowd was wowed by the designs when the Whitney Museum of American Art introduced a collection of the hand-stitched throws in November 2002. Today a Gee’s Bend quilt can fetch between $1,000 and $20,000.

WHY HAS GINGHAM BEEN A STAPLE OF Southern life since early colonists brought this English and French cloth to the region? For one, the cotton fabric is thin and breathable (ideal for humid summers and hot kitchens). It is also eminently versatile: the signature cross-check pattern goes with everything, has no right or wrong side, appearing the same whether worn outside-in or inside-out, and transcends occasion, making it appropriate for tablecloths and aprons, dress shirts and summer dresses, Texas bandannas and Patsy Cline’s stage costume.

THAT THING GRABBED MY CHICKEN BY THE tenders and held him underwater till he like to drowned.” I’ll bet you have never heard anybody say anything like that. Partly because nobody would ever volunteer that his fighting rooster was nearly killed by a duck. But mainly because “chicken tenders” are not parts of a chicken. And yet pretty nearly everywhere fried chicken is sold, one way it comes is in these boneless, gristle-less, anatomy-unrelated “tenders.” Like so many other things today, tenders are about 10 percent chicken and 90 percent marketing.

I was reflecting on this fact in a Popeyes in Greenville, Mississippi, recently, when my eyes strayed over to the buffet. Not every fried-chicken outlet has a buffet, but this did, perhaps because it was Southern, and on that buffet was a big pan of things that are very much actual working parts of the actual birds known as chickens: chicken gizzards.

And I bought me some. And I chewed. And chewed.

The gizzard is what a chicken has instead of teeth. When you are chewing a gizzard, you are having the rare experience of chewing what chews. Where else in the food chain are you going to get an experience like that? If eating pigs’ feet puts a spring in your step, you might in effect be trotting on the trotters; but that’s a big if.

Here’s how chicken digestion operates. When a chicken pecks up a bug, say, it swallows it down to the crop, also known as the craw, as in “This whole concept of chicken tenders just sticks—figuratively speaking—in my craw.” The crop holds the bug and marinates it in digestive juices until the gizzard croaks (or maybe not croaks, but some kind of gravelly tone), “Okay, gimme what you got.” And the gizzard’s wrenchy slaunchwise muscles and its “horny callosities” (to quote one technical description), and the bits of grit and gravel that the chicken swallows in order to assist the gizzard, go to work on that bug until it turns into . . .

What would you say it turns into? I would say it turns into proto-chicken. Let’s set aside that old conundrum of which came first, chicken or egg. The chicken gizzard is where chicken begins.

Here, from The Birder’s Handbook: A Field Guide to the Natural History of North American Birds, is a tribute to the gizzard: “. . . objects that required more than four hundred pounds of pressure per square inch to crush have been flattened within twenty-four hours when experimentally fed to a turkey.”

Aside from Molly Bloom saying Yes and Yes and Yes so expansively at the end, what does any reader of Ulysses, by James Joyce, remember? “Mr. Leopold Bloom ate with relish the inner organs of beasts and fowls. He liked thick giblet soup, nutty gizzards . . .” and so on. Joyce himself obviously relished that passage, because further along in the book he’s still tasting it: “As said before he ate with relish the inner organs, nutty gizzards . . .” and so on. What a comedown it would be if Ulysses were written today, and Mr. Bloom ate without effort odd notional figments of fowl.

There’s an Uncle Remus story, “Brother Rabbit and the Gizzard-Eater,” which ends (spoiler alert) in Brer Rabbit cackling:

“You po’ ol’ Gator, ef you know’d A fum Izzard,

You’d know mighty well dat I’d keep my Gizzard.”

But gizzards are not always cherished things, in literature. For a serious person to concern himself with conventional politics, wrote Henry David Thoreau in his essay “Life Without Principle,” would be “as if a thinker submitted himself to be rasped by the great gizzard of creation. Politics is, as it were, the gizzard of society, full of grit and gravel, and the two political parties are its two opposite halves . . . which grind on each other.”

I hear that, all right. And maybe a chicken would rather have some slicker method of digestion. Peel the outer layer off an uncleaned gizzard and you are likely to find all manner of inorganic detritus. Human heartburn must be a piece of cake compared with chicken gizzardburn.

But that’s the chicken’s problem. The toughness that the bird requires in this vital organ translates into this indubitable virtue for whoever undertakes to eat one: the longer you have to chew on something, the longer you get to taste it.

THIRTY MILLION OR SO COPIES LATER, Margaret Mitchell’s sweeping 1936 historical novel, and its Oscar-winning film adaptation, leave a complicated legacy. Opening at the outbreak of the Civil War, the thick tome follows the Georgia belle Scarlett O’Hara from her Clayton County plantation through Reconstruction in a torched-by-Sherman Atlanta. The tale often gets dumbed down to that of an epic love quadrangle between Scarlett; her scoundrel husband, Rhett Butler; her first love, Ashley Wilkes; and Ashley’s wife, Melanie. Or boiled down to its indelible lines, from “Fiddle-dee-dee” to “Tomorrow is another day” to “My dear, I don’t give a damn” (a screenwriter added the “frankly” later). But the onetime Atlanta reporter saw the novel’s theme as survival—not just of the “Lost Cause” Confederate mythology that permeated her upbringing and spurred the book. Mitchell actually seems to reject romanticizing of the Old South through her heroine, who largely forsakes antebellum social expectations and post–Civil War pouting in favor of making money and moving forward. That mindset becomes an apt metaphor for the “New South” itself, the ideals of which were perhaps best embodied by the city where Mitchell lived, worked, and wrote. But critics have noted Mitchell also treats slavery and the plight of African Americans as a one-dimensional backdrop to the action, using racist epithets and perpetuating stereotypes, like that of the loyal, master-loving slave.

Ironically, Hattie McDaniel became the first black actor to win an Academy Award for her portrayal of one of those devoted slaves, Mammy, in the director David O. Selznick’s 1939 film—the Atlanta debut of which the city’s segregation laws barred her from attending. Still, Vivien Leigh’s Scarlett and Clark Gable’s Rhett immortalized Mitchell’s memorable duo for decades to come, inspiring official and unofficial sequels, spin-offs, parodies, painted porcelain, dolls, conventions, doodads, gewgaws, a famous Carol Burnett sketch, and legions of superfans called Windies. A 2014 Harris Poll reinforced the story’s unfading popularity, ranking GWTW as the second-most popular book in America—just behind the Bible.

LIKE THE NAMES OF SEVERAL OTHER TASTY Southern staples—okra, gumbo, yam—this term for peanuts got its name from West Africa. Scholars generally trace the word back to nguba, which originally meant “kidney” (and then referred to the kidney-shaped legume) in the Bantu languages Kikongo and Kimbundu, and which slaves brought with them around the 1830s. (On a much more recent trip to Africa, the travel writer Paul Theroux learned a Kikongo proverb—Ku kuni nguba va meso ma nkewa ko—that recommends discretion: “Don’t plant peanuts while the monkeys are watching.”) During the Civil War, some people referred to North Carolinians as “goobers”; at times, natives of Georgia have been called “goober grabbers.” See Peanuts.

Last night I saw Lester Maddox on a TV show

With some smartass New York Jew

And the Jew laughed at Lester Maddox

And the audience laughed at Lester Maddox too

Well he may be a fool but he’s our fool

If they think they’re better than him they’re wrong.

THOSE WORDS OPEN THE SONG “REDNECKS” on Randy Newman’s 1974 album Good Old Boys, one of the most insightful musical meditations on Southern identity the twentieth century ever produced.

Born in Los Angeles, Newman, who went on to win fame as a movie composer, knew the South. He had spent his youth bouncing around Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, visiting his mother Dixie’s family in New Orleans, while his father served as a doctor in World War II. Newman, whose parents were raised Jewish, conceived “Rednecks” after watching the talk-show host Dick Cavett berate Maddox, the segregationist governor of Georgia, during a televised conversation in 1970. “The audience hooted and howled, and Maddox was never given a chance to speak,” Newman said later, explaining his motivation.

On Good Old Boys, Newman channeled various Southern personas. Foremost among them: a white Birmingham steelworker who witnessed Maddox’s televised embarrassment, and Huey P. Long, the demagogue Louisiana politician who favored silk pajamas and luxurious hotel suites but proclaimed himself a man of the people. Through those characters, he told a complicated story of a conflicted South.

Warner Bros. Records described the album as a “collection of Newmanesque glimpses into the collective mind and past of a maligned, neglected and vital portion of America: the South.” Released in September 1974, it reached No. 36 on the Billboard charts. That October, Newman, accompanied by guitarist Ry Cooder and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, premiered the work at Symphony Hall in the South’s capital city. Maddox, elected governor in 1966 after infamously refusing to integrate his restaurant, passed on an invitation.

At a time when dramatic changes buffeted the region, Newman connected the fates of poor whites and poor blacks, historically pitted one against another by power brokers who divided to conquer. In “Rednecks,” Newman also targeted the hypocrisy of Northerners who convinced themselves that the South was a hive of racism outside the virtuous North. He mocked the idea of a Northern promised land, likening the ghettos of the Hough in Cleveland and Boston’s Roxbury to cages.

Good Old Boys also critiqued the American experiment. Newman recorded “Mr. President (Have Pity on the Working Man)” on the night in 1974 when Richard Nixon resigned the presidency. A plea to embattled president Herbert Hoover, who failed Louisiana voters after the Great Flood of 1927, the song sounded to listeners like a takedown of Nixon. Circa 1974, Newman was hip, the literate auteur of the rock-and-roll set. Glenn Frey, Don Henley, and Bernie Leadon of the Eagles, the American supergroup of the moment, accompanied Newman on “Rednecks.”

While many albums sound dated a year after their release, Good Old Boys has remained relevant. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina and the man-made disasters that followed, the song “Louisiana, 1927” became a favored dirge for a deluged people. Simple in structure, the song drives its message with a repeated couplet, “Louisiana, Louisiana / They’re trying to wash us away.”

Newman argued, through songs buoyed by wry humor, that if you love a place, you have a responsibility to criticize it. Johnny Cutler’s Birthday, the original title for the material that would become Good Old Boys, sounded like a modern opera for the years after the civil rights movement. When Newman released a remastered version of Good Old Boys in 2002, he included the demo tapes for that earlier version of the album. They showcase the breadth of his vision. They make clear, too, his aim to create a kind of Southern pageant.

“Sail Away,” the title track on the album of the same name, broadcast a similar ethic. Released two years before Good Old Boys, the song offered a prelude of what was to come. Written from the perspective of a slave master recruiting laborers from the Rice Coast of West Africa to board a ship bound for Charleston Harbor, it’s one of the harshest indictments of the South ever written:

Ain’t no lions or tigers, ain’t no mamba snake

Just the sweet watermelon and the buckwheat cake

Everybody is happy as a man can be

Climb aboard, little wog, sail away with me.

Like much of the Newman oeuvre, it’s a pleasant little ditty, layered with lacerating observations.

WHEN DOLLY PARTON SENDS HER HOLLYWOOD friends a gift, it’s often a box of Goo Goo Clusters, Nashville’s famous candy bar—created by the Standard Candy Company with layers of marshmallow nougat, caramel, and roasted peanuts draped in milk chocolate. In the era B.G.G.C. (before Goo Goo Clusters), candy bars had only one main ingredient, so the arrival of the hand-dipped disk-shaped treats in 1912 blew the minds of sweet-toothed Southerners, who picked them up at local pharmacies. They were such a hit that the company became the main sponsor of the Grand Ole Opry radio broadcast for forty years (“Get a Goo Goo . . . it’s gooooood!”). During the Great Depression, the slogan became the quaint (though in hindsight preposterous) “A nourishing lunch for a nickel.” Originally the Goo Goo was sold without a name, but as legend has it the candy’s coinventor Howard Campbell was riding on a streetcar and telling fellow passengers of his infant son’s first words—“goo goo”—and had an epiphany of sorts. The recipe has remained nearly the same for more than a century, though the company now uses fancier peanuts and offers versions with pecans and peanut butter. There’s even a Goo Goo Finder app to locate your nearest fix.

GRACELAND IS THE 17,000-PLUS-SQUARE-FOOT home in Memphis where Elvis Presley lived for twenty years, until his death in 1977. It is now a museum, a historical landmark, and the second-most-visited private home in America (after the White House), with 650,000 visitors annually. Visitors have included George W. Bush, Jimmy Carter, and Japanese prime minister Junichiro Koizumi. Graceland has been deservedly ridiculed for looking more like a movie set than a home. Elvis’s bedroom (pink bedspreads, red telephone, stuffed hound dog) is often compared to a teenage girl’s boudoir. The TV room featured three television sets side by side, an idea inspired by Lyndon Johnson, who wanted to monitor all three major networks at once. Living in the era before remote control, Elvis once shot a TV rather than leave his chair. “Let’s face it,” said one longtime associate of Presley’s, “if something wasn’t overdone, it was abnormal to Elvis.” True enough. But to visit Graceland is also to encounter a fundamental innocence suddenly given free rein, as if a twelve-year-old had suddenly come into great wealth. The breathtakingly garish Jungle Room—arguably the proto–man cave—is an example. In one account of its creation, Presley’s father said he’d just seen a window in Donald’s Furniture Store of Hawaiian-themed furnishings, the ugliest thing he’d seen in his life. Upon hearing the details, Presley said, “Good, sounds like me.” The next day, his father returned to find that the entire display had been installed in Graceland, where the boy king sat laughing.

IN LESS THAN A DECADE, THE GRAND OLE Opry—the longest-running radio broadcast in U.S. history—will celebrate its one hundredth anniversary. This may seem like a long time to some. I’ve played the Opry many times, and when I think about what a cultural legend the show has become, a century sounds surprisingly young.

The program began on November 28, 1925, as an hour-long radio “barn dance” produced by an outspoken radio personality named George D. Hay; by the 1930s, it expanded to four hours, and the signal reached more than thirty states. Many people are still around to reminisce about gathering near the radio on Saturday nights, tuning in to WSM-AM. It seems like such a sweet and simple time: families connecting by sitting together and listening to country, bluegrass, folk, gospel, comedy—sounds that made them laugh, cry, dream, and feel certain they knew exactly how the singer felt in that moment. Sometimes when I’m on tour, I’m lucky enough to meet one of these old-timers. They tell me stories of Mama sewing and Daddy tapping his feet to the big sounds coming from their little radio. Today it seems mind-boggling to think that people had nothing else to do on Saturday night but sit and listen with the ones they loved the most. But to me, nothing sounds sweeter.

Of course, over the years millions have also attended the Opry in person, and if you never have, you should—you just might witness history in the making. After the show moved to a more permanent home in downtown Nashville, the famed Ryman Auditorium, aka the Mother Church, in 1943, that venue hosted some pretty incredible moments. Here’s a sampling:

June 11, 1949: My grandfather Hank Williams made his Opry debut. (He had first auditioned nearly three years earlier, but was rejected.) The crowd went wild, and he ended up playing six encores, the first and to this day the only Opry performer to do so. Sadly, he was fired in July 1952 over his ongoing struggles with alcohol, and never reestablished his connection to the Opry. He died just six months later. Today he’s regarded as one of the show’s first worldwide stars: the “Hillbilly Shakespeare.”

October 2, 1954: A nineteen-year-old boy from Mississippi appears for the first time on the Opry stage. Although the audience reacted politely to his rockabilly tunes, after the show Opry manager Jim Denny told the young man’s producer, Sam Phillips, that the singer’s style did not suit the program. Elvis Presley never performed at the Opry again.

January 20, 1973: Jerry Lee Lewis used his forty-minute Opry slot to wreak revenge on certain Nashville music-industry people who he felt had shunned him some eighteen years earlier. The producers laid down stern ground rules before Lewis’s performance: no rock and roll, and no profanity. Onstage, Lewis proceeded to play plenty of rock and roll and to refer to himself as a “motherf**ker.” He was not invited back.

I have released three albums and had the good fortune to tour around the globe, but there’s nothing like coming home to that Grand Ole Opry stage. In 1976, the Opry House opened nine miles from downtown Nashville to accommodate larger crowds. A circular wooden piece of the original stage at the Ryman was transplanted to the front and center right of the Opry House stage, where the musicians stand and sing. Brad Paisley once said that the dust from my grandfather’s boots could still be on that hardwood floor. Every time I stand there, I look a little harder.

WHETHER DRESSING A HOLIDAY FEAST OR partnering with ham at breakfast, gravy usually starts with pan drippings. Sawmill gravy calls for a fat-and-flour roux, milk, and crumbled sausage. Cornmeal gravy substitutes a more affordable starch for flour, while tomato gravy has long drawn on the bounty of the garden or a well-stocked pantry. Appalachian cooks make redeye gravy from country ham drippings, coffee, and brown sugar. Then there’s rich, syrupy chocolate gravy. You can hardly go wrong pouring any of them over a hot biscuit. See Redeye gravy; Sawmill gravy.

(1946–)

WITH HIS SILKY, SEDUCTIVE VOCALS AND PRODUCTION by Memphis’s Hi Records boss Willie Mitchell, Al Green had a run of hits in the early 1970s that has fueled jukeboxes and wedding bands all over the world. “Let’s Stay Together,” “Here I Am (Come and Take Me),” and “I’m So Tired of Being Alone” propelled Green to superstardom, with his devastating falsetto and intimacy replacing the heft of predecessors Otis Redding and James Brown. In 1974, a jealous girlfriend, Mary Woodson, poured boiling grits on him while he was in the bath—she would shoot herself in the head shortly after—and Green took that as a sign from God that he needed to change his life, going on to devote most of the rest of his career to gospel music. If you’re in Memphis on a Sunday, a stop at his Full Gospel Tabernacle church in South Memphis is a must no matter what you believe.

COLLARD, MUSTARD, TURNIP, CABBAGE. WE all know those greens, but the Southern roster doesn’t end there. Cabbage collards are the sweet, tender pride of Ayden, North Carolina. Appalachian cooks celebrate winter’s end with foraged wild varieties such as creasy greens, poke sallet, and sochan. Sweet potato greens are finally catching on with a wider audience. Not all leafy vegetables get the same treatment. Some simmer for hours, yielding a dark, nutritious potlikker, while others only need a quick toss in the skillet. But if you’re getting greens, you can usually count on a warm, soul-satisfying side. Because around here, the word greens rarely refers to salad.

GROUND CORN OF THE DENT (OR FIELD) VARIETY, simmered in liquid until porridge-like, grits have been a part of mealtime in the Americas since before the first European explorers set foot in Florida. More than rice, they are the foundational starch of the Southern diet, mixed with anything from butter to cheese to shrimp and sausage, and they can ignite the sort of controversy that also dogs the likes of buttermilk biscuits and pimento cheese. Some cooks simmer grits with milk or cream, others settle for tap water, still others insist on spring water. The only required seasoning is salt. And although menus rarely distinguish between white and yellow grits, many cooks do. Grits milled from white corn traditionally serve as a discreet backdrop for the likes of tomato-sauced shrimp and the pounded and braised hunks of meat known in New Orleans as grillades. Yellow grits are generally sweeter and taste more like corn. One higher-end purveyor has recently introduced blue corn grits, which have a nutty flavor. So say the connoisseurs, anyway; plenty of others insist they can’t taste the difference. But whether a professional chef or a casual eater, no self-respecting Southern cook will defile a cooking pot with instant grits, which are to the genuine article what Tang is to fresh-squeezed juice. To paraphrase the great Leah Chase, a ninety-something chef who still presides over the kitchen at Dooky Chase’s Restaurant in New Orleans: if you can’t take the time to make grits the right way, fix a ham sandwich or fry an egg and get out of the kitchen.

GOLIATH GROUPERS ARE THE GIGANTIC FISH seen hanging next to fishermen half their size in old snapshots and postcards from the Gulf Coast. The world record, a 680-pounder, was caught on May 20, 1961, off Fernandina Beach, Florida. Nearly wiped out by overfishing, goliath groupers are now a protected species; but recreational fishermen still catch many other varieties, including red, black, yellowmouth, and Warsaw groupers, especially in Florida.

Stricter limits on commercial grouper fishing have made the once cheap and plentiful fish more expensive. Chefs prize grouper for its mild and sweet flavor and heavy-flaked dense meat. The grouper sandwich was once an icon of Old Florida cuisine, but nowadays the genuine article is harder to find. In August 2006, the Tampa Times reported that out of eleven “grouper” sandwiches purchased at local Tampa Bay restaurants and turned over to scientists, only five actually contained grouper. The six impostors contained tilapia, Asian catfish, hake, and an unidentified species. The researchers found that expensive restaurants advertising “bronzed grouper” were also serving tilapia. Caveat emptor. And it’s almost certain that none of them contained “square grouper,” a nickname the U.S. Coast Guard coined to describe bales of marijuana floating in the Gulf of Mexico after being thrown from airplanes for retrieval by boat, or abandoned by smugglers trying to avoid arrest.

H. D. GRUENE BUILT GRUENE (PRONOUNCED: green) Hall in 1878 as a small spot for local farmers, cowboys, and families to gather and dance the weekend away to German-style polka music. Today, Texas’s oldest operating dance hall is a country-music holy site, annually drawing thousands of the honky-tonkin’ faithful to a tiny town (not even a stoplight) wedged between San Antonio and Austin. Gruene has hosted the likes of Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, Jerry Lee Lewis, Merle Haggard, and many more—and hasn’t much changed since its construction. The high-pitched tin roof still rattles when it rains (seldom), a cold-beer-stocked bar sits up front (with plenty of Lone Star), and holes in the original oak floors are patched up with old license plates. And no, there’s no AC. But within the 6,000-square-foot, 800-person-capacity hall lives an energy that continues to attract, and attract again, country music’s most fabled artists, and newcomers to boot.

FOR A GOOD CHUNK OF THOSE BELOW THE Mason-Dixon Line, going to the beach means going to the Gulf Coast, accessible to many Southerners by a drive of three hours or less. Five states—Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas—share its 1,680 miles of U.S. coastline. To many, however, the Gulf Coast refers to the Redneck Riviera (or Emerald Coast, depending on your net worth). As Tom T. Hall put it in his song of the same name, “Gulf Shores up through Apalachicola they got beaches of the whitest sand / Nobody cares if gramma’s got a tattoo or Bubba’s got a hot wing in his hand.” This 100-mile stretch of the Florida Panhandle is a democratic place. You can hole up in a multimillion-dollar gated community or plunk a folding chair right down in the water at a public beach where they’re not sticklers about alcohol or, in some cases, clothing. Either way, you’re wiggling your toes in the finest, purest, most powdery white sand in the country, according to “Dr. Beach” (aka Dr. Stephen Leatherman, director of the Laboratory for Coastal Research at Florida International University). It’s because wave action has ground to dust the softer minerals, leaving only the hardest—quartz crystals. And those it has pounded to “terminal size,” meaning as small and uniform as possible. Which is why it’s so damn hard to wash them out of certain parts of your body, be you male or female.

THE TERMS REFER TO THE DESCENDANTS OF enslaved West Africans along the Lowcountry coast—Gullah in South Carolina, Geechee in Georgia—and may have been derived from Gola and Kissi, West African tribes. They still retain their own language, culinary traditions, music, art, and beliefs—a unique treasury of culture that has survived centuries.

Justice Clarence Thomas is Geechee. Tim Scott, the only black man in the U.S. Senate, is Gullah. So is Michelle Obama, with grandparents hailing from the South Carolina rice fields. Ditto Darius Rucker and Smokin’ Joe Frazier, who grew up in Beaufort County.

Assimilation worked its dubious ways, and by 1970, Gullah/Geechee culture seemed destined for the scrap heap of American history. But growing awareness has helped protect it. There are university classes now, and even a Gullah New Testament. Most notably, there’s Beaufort, South Carolina’s Gullah Festival each Memorial Day, “Decoration Day” to the Gullah. A brass band leads a parade to the riverbank, where people toss extravagant garlands upon the waters, honoring the Union Navy that set their forebears free in 1861.

PEOPLE WHO ORDER GUMBO IN RESTAURANTS distinguish different versions by the kind of protein used. They may prefer the gentle spice of, say, chicken and andouille gumbo to the oceanic funk of crab and oyster gumbo. People who actually prepare gumbo, however, classify it by the thickener used. Different gumbos get their spoon-coating texture from filé (ground sassafras leaves), roux, okra, or some combination of the three. Rules exist—use okra with oysters, roux with wild turkey—but these rules aren’t broken so much as beset by endless fractal variation. The Creole gumbo of New Orleans tastes stylistically different from the Cajun gumbo of the country. Coastal gumbos almost always pool around a mound of rice, but the Cajun cooks of inland Avoyelles Parish will more likely serve their gumbo with a roasted sweet potato. Just remember: if you are in New Orleans and someone is having a gumbo, by all means go. Having a gumbo in the Crescent City is like having a barbecue elsewhere; it’s a feast with roux-dark soup as the centerpiece.