TALK ABOUT BIRDS TO YOUR AVERAGE Northerner and you’ll be talking backyard jays and thrushes. Talk about birds to a scientist and you’ll be talking bipedal, endothermic egg-laying vertebrates, flighted and flightless, all feathered, hummingbirds to condors, some ten thousand distinct species. Talk about birds to a hunter and you’ll be talking game birds: ducks, brant, coots, gallinules, grouse, geese, scoters, turkeys, pheasant, doves, and in some locales, cranes, and even bustards. Bustards? Bustards!

But if you’re talking birds to a Southern sportsman, it’s like no other bird exists. You’re talking the king, the northern bobwhite quail, Gentleman Bob, Sir Colinus virginianus. There is more flavor in a four-ounce quail than in an entire factory-farm frying chicken. Stuff a dozen with short sticks of andouille sausage, wrap ’em with pepper-cured bacon, pin them tight with toothpicks, and throw them on the charcoal. Done when the andouille bubbles. Make your tongue beat your brains out.

Bob is a gentleman and a sport, but he keeps himself close to home. Quail covey up in extended family groups and skitter here and there, scratching and scrabbling among the underbrush, but they whistle one another home each sunset, bob-white, bob-white.

A covey needs everything—food, water, and an owl-proof blackberry bramble—within a quarter mile, and small farms across the South provided perfect habitat. Quail populations exploded after the Civil War, when several million of the freshly emancipated hacked out farmsteads in the pinelands. But farmers got fewer and farms got bigger until six hundred, eight hundred, a thousand acres was a middling field, monocultures of cotton, peanuts, corn, and beans. Throw in a plague of fire ants, insecticides, and herbicides, and statutory protection of hawks and owls, and quail numbers plummeted. Isolated populations remained in the Red Hills of Southwest Georgia, the Alabama Black Belt, and West Texas, but throughout most of the South, the explosive whir of a covey rise was just a sweet memory.

Quail hunters, though, were not about to watch their birds go the way of the dodo. And the love of a four-ounce bird drove them crazy: habitat recreated; land leased, bought, and sold; crops planted and left unharvested; birds hatched, raised, and released. Entire fortunes squandered, wives and mistresses estranged, bitches bred and pups whelped, horses and mules bred. University courses in quail management, master’s degrees and PhDs. Britches and shotguns ordered custom fit, bourbon by the barrel, vets by the battalion, hay and cedar-chip dog bedding by the ton. Ten billion dollars and counting.

Forget Cape buffalo, old nyati, “the Black Death.” He may tread upon you, gore you, hook you, and throw you into the mopane bushes, but he will leave your wallet alone. The diminutive bobwhite quail is the most dangerous game animal on earth. Bernard Baruch, “the Lone Wolf of Wall Street,” had a quail plantation. Henry Ford and R. J. Reynolds Jr. did, too. Ditto Robert Woodruff, president of Coca-Cola. An invitation to shoot with any of them was like an invitation to the royal box at Ascot. But most of us have to pay, and pay dearly, at venues across the South. Walk behind stalwart pointers? You can do that. Ride in a bird buggy behind a Jeep? Sure. A yellow-wheeled, rubber-tired wagon pulled by a matched team of redbone mules, with a gentleman at the reins? Priced accordingly. Maybe two grand?

Beware, quail might drive you crazy, too.

(1886–1939)

NOW REMEMBERED AS THE MOTHER OF THE Blues, Ma Rainey was known in her time as the Gold-Neck Woman of the Blues and the Paramount Wildcat, nicknames that reveal how she became one of the South’s most popular songstresses. Generations of blues fans forgot that in her time, contemporaries of Rainey swore that she outperformed her fellow African American blueswoman Bessie Smith (whom, contrary to legend, Rainey did not kidnap and force to join her vaudeville revue). Rainey was born Gertrude Pridgett in 1886 in Columbus, Georgia, a port town with a busy calendar of traveling minstrel shows. She joined the circuit in 1904, touring with the Rabbit Foot Minstrels. A decade later, she and her husband created their own act, Rainey and Rainey, Assassinators of the Blues. She started taking the stage solo after signing with the Paramount label in 1923. Audience members were bewitched by her down-home patter and distinctive look: Rainey wore an untamed horsehair wig, gold caps on her teeth, chains of gold coins around her neck, and so much skin lightener that she had a golden glow. But Paramount did a disservice to her strong voice: notorious for its frugality, the studio made its artists sing into amplifying horns, and then released their music on cheap shellac. The surviving records’ poor quality long subdued the blues world’s respect for Rainey.

APPALACHIAN PEOPLE DON’T SEE MUCH green in the woods between the fall avalanche of orange and the spring emergence of ramps, which helps explain why they get so excited about these garlicky wild leeks each year. Ramp festivals have drawn crowds for generations: West Virginia’s Feast of the Ramson dates back to 1937, seven years after North Carolina’s first Ramp Convention. Mountain cooks sauté ramps with scrambled eggs and potatoes, and pickle them to prolong their short season. Generally, they know better than to eat the pungent alliums raw. (Stories abound of children being sent home from school for stinking up their classrooms.) Chefs around the country look forward to ramp season now, too, cooking the newly trendy ingredient just about every way you can imagine, which is putting pressure on a limited natural resource. Do your part by harvesting only the greens, leaving behind the bulbs and roots to regenerate—both for the old-timers and for the next umpteen waves of foragers about to “discover” them.

(1896–1953)

ALTHOUGH HER RURAL ROOTS WERE OBSCURED by the circumstances of her birth in 1896 in Washington, D.C., the foremost chronicler of Florida’s backwoods came from a farming family. Rawlings’s father, a patent examiner, pined for his parents’ Maryland farm, while her mother spoke longingly of the southern Michigan homestead where she had grown up. “We cannot live without the earth or apart from it, and something is shriveled in a man’s heart when he turns away from it,” Rawlings wrote in Cross Creek, a memoir of her years spent as an orange grove keeper. Rawlings described the writing process as “agony” but had enough confidence in her craft to retire from the Louisville Courier-Journal at age thirty-two. Two years later, Scribner’s published her literary sketches of the nature and neighbors she encountered in marshy central Florida, marking the start of Rawlings’s lifetime professional relationship with the editor Maxwell Perkins. He helped nurture a string of novels populated by palmetto trees and alligator hunters, culminating in The Yearling, which in 1939 won the Pulitzer Prize. Rawlings’s career faltered after a friend she had described in Cross Creek as an “ageless spinster” sued her for invasion of privacy.

NO MONDAY EVER PASSES FOR ME WITHOUT the thought of red beans and rice floating through the transom of the day’s culinary opportunities. I love it like few other dishes. There is little, probably nothing, I cook more frequently, and there’s absolutely nothing I crave more deeply (this from a man who has opened more than one restaurant inspired by a craving or two).

Red beans and rice seems to have become the New Orleans Monday house favorite at least a century and a half ago, for a couple of reasons. Sundays there have always been days for festive eating. Families cooked big meals after church or dined at old-line French Quarter restaurants. Neighborhood mom-and-pop places did a brisk business as well. As a result, Monday became the food-service day of rest.

For house servants, Monday was also the traditional laundry day. The chore of handling a big family’s week of laundry, washing, drying, folding, and pressing could be a Herculean task. So something like red beans—requiring little more than Sunday’s leftover ham bone, minimal chopping and dicing of vegetables, and a very low flame that could be left for hours without much tending—would be the perfect dish for a cook plugging away at a lengthy task away from the stove.

As restaurants blossomed, laundry days got less complicated and our lives became more so. Red-bean Mondays became a citywide restaurant theme. Everyplace from Commander’s Palace to Fat Harry’s offered a plate of red beans that day. No two versions are the same, and the pride a New Orleans cook takes in his red beans is as serious as in his or her bordelaise, grillades, or daube glacé. It’s a badge of honor. But pride doesn’t prevent plenty of cooks I know from admitting without remorse that Popeyes, as corporate a chain as there is, has a formidable recipe. (A quick web search brings up dozens of copycat versions. I’ve attempted several, and none approach the original.)

I have spent decades refining my own recipe. I’ve altered techniques, soaking beans overnight, giving them a quick boil, and letting them sit for an hour before cooking. I’ve gravitated back and forth between neck bones/hocks and andouille sausage for flavoring. I’ve added sugar or cane syrup or both, and alternated between fresh and powdered garlic. Next Monday, I will most likely have a slightly different take, if only to perpetuate my twisted pursuit of something I’m not sure even exists: the perfect bowl of red beans and rice.

The closest to that I’ve experienced was served around a table every Monday, once New Orleans reopened after Katrina, in late 2005. The food writer Pableaux Johnson gathered a group of folks weekly around his table. His door was open to all. Most of the same few people would arrive in early evening. Often, friends of friends drifted in, the smell of red beans and andouille in the air. In those dark months of despair and confusion, Mondaynight red beans were a weekly beacon of hope, the finish line of another week of recovery, a moment of joy with friends.

In the years since, Pableaux and I have taken to debating the merits of different techniques and recipes. His Southwest country recipe is in direct opposition to my citified take. I know, however, that it never really comes down to whose is better than whose, but rather that the tradition remains—a tradition never more important than on those Mondays after the storm, when everyone needed comfort, my friend’s door was always open, and there was a bowl and a spoon for whoever crossed his threshold.

(1941–1967)

A GEORGIA NATIVE WHO GOT HIS START AS A member of Little Richard’s backup band, Otis Redding was soul music’s beast. Built like a linebacker, he refined “deep soul,” a sound that married frenetic, greased-lightning party numbers with raw, scarred ballads. In the process, he became the cash king for Memphis’s Stax Records, recording hits such as “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long” and “Mr. Pitiful.” Redding’s initial audiences were almost exclusively black until 1967, when he headlined the Monterey Pop Festival, performing a short but career-defining set that won over the mostly white audience and made fans of groups like Jefferson Airplane and the Rolling Stones (whose “Satisfaction” Redding covered during his performance). Poised for a commercial breakthrough, Redding quickly went back into the studio and recorded the single “(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay,” showcasing his softer, more reflective side. Then, a tragedy: on the early morning of December 10, 1967, Redding was killed in an airplane crash in Wisconsin that also took the lives of four members of his backing band, the Bar-Kays. His single, released posthumously a month later, would become not only Redding’s sole number-one hit but arguably one of the greatest songs in music history.

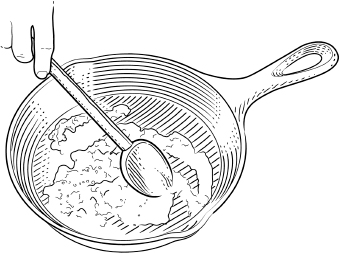

SLAP A SLAB OF COUNTRY HAM IN A HOT cast-iron skillet, remove it when both sides are browned and curling, and repeat with as many slices as you have mouths to feed. Then pour in half a cup of hot coffee, scraping up all the orange-colored ham bits left behind on the bottom of the pan and stirring until an oily red-tinged “eye” forms in the center, and you’ll have redeye gravy. With no flour to thicken the mix, it’s technically less a gravy than a pan sauce. But regardless, the combination of two potent flavors—the intense saltiness of country ham and the bitterness of black coffee—is a stroke of Southern genius and an excellent accompaniment to buttermilk biscuits.

THE RISE OF THE REDFISH TO ICONIC HEIGHTS links directly to Paul Prudhomme, the late, beloved Cajun chef whose rightfully revered signature dish, blackened redfish, shone a floodlight on the saltwater species in the 1980s. In turn, commercial fishing took a harsh toll on redfish populations. But staunch conservation measures fueled their recovery, and these days the fish’s brawny attitude and everyman appeal has given rise to redfish mania among anglers. The fish prowl nearshore breakers, marsh creeks, and inlets, and can be caught with utilitarian curly-tailed jigs, chunks of dead bait, and highfalutin hand-tied flies alike. In varying parts of the South they’re known as red drum, channel bass, and occasionally spottail, but “redfish” is slowly becoming ubiquitous. Regardless of what you call them, these fish, which can grow to ninety pounds, support a massive recreational fishery from Texas to Florida to Virginia. See Prudhomme, Paul.

CLARKSDALE, MISSISSIPPI, HELPED BIRTH THE blues—it’s where Robert Johnson supposedly cut his fabled deal with the devil. But to capture true Delta magic, head to Red’s Lounge, one of the few remaining clubs with a genuine juke-joint vibe. Crimson lights. No frills. Odds-and-ends chairs so close to the “stage” (actually just a carpet on the floor) that you can reach out and touch such ax icons as R. L. Boyce and Leo “Bud” Welch when local talent lays it down on Wednesday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday nights. Strike up a conversation with some of the Brits or Germans who’ve made the pilgrimage, too, while pulling on a Budweiser tall boy dispensed by the owner, Red Paden. When the lovable curmudgeon isn’t behind the tiny bar, he’s tending the chicken and ribs he has going on a smoker out front. But the real sizzle is inside.

EVERYBODY KNOWS ABOUT THE GRAY WOLF—that thing howling against the moon on airbrushed T-shirts at the county fair. Gray wolves are even nicknamed “common wolves.” But there’s another wolf in North America, native only to the South: Canis rufus, the red wolf. Once populating a stretch from the mid-Atlantic to Florida, red wolves—derided for years as “the devil’s dogs”—were hunted feverishly. Because of that, along with drastic loss of habitat, they were declared extinct in the wild in 1980, when seventeen of them were captured for breeding. To conservationists’ pleasant surprise, those captured wolves bred successfully, and before long biologists reintroduced them to North Carolina’s Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, where about a hundred red wolves roam today. Sized somewhere between gray wolves and coyotes, red wolves are the shade of dried pine straw lit by sunset, a helpful camouflage in the Southeast’s piney forests. Now listed as an endangered species, red wolves rely on that camouflage—as well as federal protection—as they struggle to reestablish a viable foothold in the Southern wilds.

(1964–)

BILLY REID HAS A KNACK FOR MAKING clothes that basically look as appropriate in Florence, Alabama—where his company is headquartered—as they would in Florence, Italy. Reid started his fashion career as a child in his grandmother’s house in Amite City, Louisiana, where his mother ran a clothing boutique. In 2010, he exploded onto the international scene by winning both the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund Award and the GQ/CFDA Best New Menswear Designer in America Award, a shocking achievement for a designer from anywhere, let alone Alabama. Embodying genteel Southern traditions and global sophistication, Reid is now a star in the constellation of the Deep South’s cultural elite. His annual Shindig in Florence celebrates the region’s wider cultural riches, featuring music from the likes of Alabama Shakes, and his boutiques, decorated with antiques, worn rugs, and mounted animal heads, also sport decanters of whiskey, ready for shoppers to sip while perusing the racks.

IT SAYS SOMETHING ABOUT THE DUALITY OF the South that one of its most prominent musical exports in the eighties and nineties was a group of aggressively liberal college-town activists from Athens, Georgia, known for mandolins, candy-colored melodies, and a song called “Shiny Happy People.” Formed in 1980 and saddled with the “alternative” label ascribed to pretty much anyone who wasn’t Bon Jovi, the foursome of Michael Stipe, Mike Mills, Peter Buck, and Bill Berry produced several underground-rattling, adored-by-undergrads albums in the Reagan era (among them Murmur, Reckoning, and Lifes Rich Pageant) before launching into the commercial stratosphere with 1992’s Out of Time. The rich, homey album—including “Losing My Religion,” its biggest moment—served as a sunny counterpoint to the band’s follow-up, the impossibly strong Automatic for the People, which included the universal heartbreaker “Everybody Hurts” and the Andy Kaufman tribute “Man on the Moon.” R.E.M.’s left-leaning activism encompassed everything from voters’ rights to LGBT issues to animal rights; Stipe once attended MTV’s Video Music Awards ceremony wearing a series of white T-shirts trumpeting assorted pet causes (RAINFOREST; HANDGUN CONTROL NOW). Though Automatic marked R.E.M.’s airplay pinnacle, the band produced albums of consistent highlights (including New Adventures in Hi-Fi and Up) before they called it quits in 2011, having sold eighty-five million records and secured a spot in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. See Athens, Georgia.

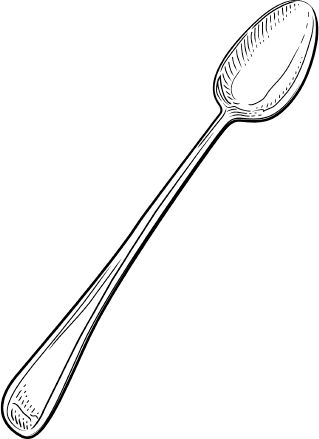

HERE’S THE QUICKEST WAY TO TELL IF A COUPLE have roots in Charleston, South Carolina: check their wedding registry for a rice spoon. To the eighteenth-century English, the long-handled utensil with its oversize bowl served as a stuffing spoon. But well-to-do colonists in the South Carolina Lowcountry—the New World’s leading rice producer—used it to dish out the lucrative grain at the city’s traditional two-o’clock dinners (not to be confused with anything as pedestrian as lunch or supper). Today most of us can’t often find time for leisurely afternoon repasts, but the spoon remains a cherished totem of Southern hospitality.

ROADKILL IS WHERE NATURE AND MAN meet in a way neither of them hoped to. It is the literal crossroads between the natural and the man-made world, perhaps the best example of our uncomfortable cohabitation with the other living things with which we share the planet. Not including insects, approximately one million animals in the United States start the day as whatever they are and end it splayed across the pavement. It’s a sad and messy state of affairs, and only one good thing can possibly come from it: dinner. Vultures, crows, foxes, possums, and some humans love to eat roadkill. It becomes part of the food chain. It may be a stretch to call this a happy ending, but it’s as close to one as roadkill allows.

Cultures are defined and exposed by roadkill. For instance, penguins are common victims in New Zealand; in Australia, wombats and kangaroos; in Montana, elk, moose, and bear. In the southern United States, the road is littered with possums and raccoon and deer and squirrels—a mishmash, a hodgepodge, real variety. As a nation we kill almost fifty million squirrels a year, and that’s just the tip of the roadkill iceberg. I live in North Carolina now, but on trips back to my home state, Alabama, I have noticed a lot of dead armadillos on the road. They weren’t there when I was a kid. Armadillos used to seem exotic to me, remnants of our Triassic past, extra-large roly-polies. Now they are just another squashable thing, and, incidentally, are dispatched by vehicles more than any other animal in America.

Under certain conditions, a small family could live off of roadkill for a while, but only if the family really wanted to. More than a million deer become casualties every year, so that’s a lot of dinner for some lucky scavengers. Precautions would need to be taken, of course. If this is something you’re interested in trying out, first remember this handy ditty: How fresh is it? How flat is it? The flatter it is, the less likely you’ll want it in the stew. Worms are also a concern, so you’ll want to cook the living hell out of it. The pros: roadkill is lean, high in protein, free of additives, and free of charge. The cons: you yourself could get run over while picking up the roadkill; you become Vulture Enemy No. 1; and you also become “the guy who eats roadkill,” a con that may also be a pro, depending on your address. Imagine finding a fresh deer carcass near a cornfield and a ditch where wild blackberries are growing. That adds up to one swanky delight, an entire meal. You could have a dinner party. Just don’t mention where you shop.

LOCATED ON A CHEEZ WHIZ STRETCH OF Lower Broadway in Nashville, Robert’s is the only honky-tonk that locals deem worth visiting. It occupies what was long the home of the Sho-Bud Steel Guitar Company, and then a liquor store during the dark days of the eighties after the Grand Ole Opry ditched the neighboring Ryman Auditorium for the suburbs. The business’s original owner, Robert Wayne Moore, jump-started the resurrection of downtown in the early 1990s when he augmented his Western wear and boot shop with live music. The stage is to your left as you walk in, the walls cluttered with all sorts of Nashville memorabilia. If it’s the weekend, saddle up at the bar and order a fried bologna sandwich and a drink and revel in the sounds of the house band, Brazilbilly—fronted by the current owner, Jesse Lee Jones—or the Don Kelley Band, some of Music City’s finest bar musicians. Upstairs, there’s a nondescript second entrance just steps from the Ryman, and many a legend has slipped through that door for a surprise set at Robert’s.

LIKE MOUNT OLYMPUS AND VALHALLA, Rock City sits atop a great mountain and looks down on much of the world. What makes Rock City different from the other two is that you can go to Rock City—you can actually see it. This is the idea, anyway, that Clark Byers tried to implant in the minds of every station wagon–ful of families traveling in, across, or through the South: SEE ROCK CITY! THE EIGHTH WONDER OF THE WORLD! These signs and similar ones were everywhere, many of them on the sides of barns. Byers painted them himself. At one time, there were over nine hundred of them, in nineteen states. Only a handful remain today.

Rock City, perched on Lookout Mountain near the Georgia-Tennessee border, does not disappoint if what you are looking to see are a lot of rocks, because Rock City is, in fact, a city of rocks. Trails snake through the many different formations, including the politically incorrect Fat Man’s Squeeze, where two big rocks are situated so closely together that only the wispiest member of your family could get through. There are also the Fairyland Caverns, and Mother Goose Village. But the real selling point, the big deal that brings thousands of visitors a year to Rock City, is this: if you stand on the very highest rock on Lookout Mountain, you can see seven states just by turning your head.

“FIRST, MAKE A ROUX.” THAT, OR SOME variation on it, is the lead sentence of almost every Cajun recipe you’ll ever encounter. The French word roux (pronounced “roo”) describes a cooked and seasoned thickening mixture of oil and flour that’s at the heart of gumbo, étouffée, and many soups, stews, and gravies. Stirring the mixture in a heavy pot on a hot stove colors the roux as the flour cooks—producing variations that include lightly cooked brown roux, medium copper penny–colored roux, and long-cooked black roux. The Louisiana chef Paul Prudhomme once warned home cooks to stir roux carefully, as just a little splash of this “Cajun napalm” on bare skin can cause severe burns. It’s also possible to purchase premade roux sold in glass jars. If you must.

THE PRIMITIVE GREEK REVIVAL ANTEBELLUM mansion in Oxford, Mississippi, built in 1844, where the writer William Faulkner lived for more than thirty years, until his death from a heart attack in 1962, and wrote most of his novels. Surrounded by twenty-nine forested acres, the renovated two-story home is now owned by the University of Mississippi and open to visitors, who come from all fifty states and dozens of foreign countries. See Faulkner, William; Oxford, Mississippi.

FIRST, YOU MUST LET BYGONES BE BYGONES. Rum was not wholly responsible for that unfortunate episode after your high-school prom, involving the neighbor’s shrubberies and two weeks of being grounded. Most of that resulted from your lack of self-discipline. Admit it.

If you’ve avoided rum ever since, you should consider how unfortunate that is. In our lifetime it has progressed from a spirit featured in trash-can fraternity-house punches to something approaching (in some cases exceeding) the best cognac: to be sipped gently and with momentary awe. Rum’s recent revival is a heartening tale. It merits revisiting and reacquaintance.

But let’s begin at the beginning. Rum is an ardent spirit made of sugarcane or its by-products. It’s historically linked with the sugar islands of the Caribbean, and thus with slavery. Rum was the cornerstone liquor of the American colonies, consumed in prodigious quantity in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries up and down the Eastern Seaboard, especially in Charleston, South Carolina, which had a direct pipeline to Barbados, where rum flowed like water. After American independence, trade complications with the rum-producing islands, combined with a surfeit of grains in the ridiculously fertile trans-Appalachian interior, led to the rise of American whiskey in general and bourbon in particular. Let us by all means salute the development of bourbon. Still, a deep-grained allegiance to whiskey does not preclude you from enjoying rum, nor admitting it was America’s original spirit.

Rum was rediscovered during Prohibition, when Havana essentially became the corner bar for much of the South. Thirsty travelers in Cuba found that the rank rum of their forefathers had been much improved—thanks in large part to the Bacardi family, which had started to tend to its product with a diligence unaccustomed among other distillers. This notwithstanding, rum failed to regain a spirit plurality during the cocktail craze of the 1930s to 1950s, largely because it labors under regrettable misconceptions. Foremost among these is the belief that, because rum comes from sugar, it must be sweet and therefore a drink for the callow and unsophisticated. This is not true.

Much of rum’s appeal today lies in its broad diversity. It’s made on scattered islands, each with its own cultural traditions and techniques. Thanks to time and technology, rum production is no longer as easily pigeonholed, geographically, as it once was, but three essential styles of it cover the general taste topography of today’s market: Jamaican-style pot-still rum (which is funky and dense), Spanish-style column-still rums (clean and light), and Martinique-style agricole rums (which tend toward vegetal and grassy). Most rum made today begins as molasses, a by-product of sugar production. But Martinican rum stands out: it’s made from freshly pressed sugarcane juice. This creates a distinctive flavor, especially in the younger white rums, which some insist require repeated tasting before one’s palate becomes sufficiently educated. This may be true.

Rum’s devil-may-care diversity may also serve as a hindrance to its wider embrace. Since each island has its own regulations on rum production, the tastes can vary such that it’s hard to predict what a new-to-you bottle will deliver. Bourbon, cognac, and Scotch are all more closely regulated at their points of origin. So basically, it comes down to a matter of personal preference: Would you like the sixty-four-color pack of Crayolas to make your drinks? Or are you perfectly content with the eight-pack?

In the past decade or two, rum has resurfaced in the South and beyond as a gentleman’s drink. Premium rums have made their way onto the shelf, many of them quite delectable; if you spend twenty-five dollars or more on a bottle, odds are you can sip it neat and not feel the need to drown it in Coca-Cola. Another encouraging trend is the return of craft rum distilling on the North American mainland, especially in areas where sugarcane grows. St. Augustine Distillery in Florida, High Wire Distilling and Red Harbor Rum in Charleston, and Old New Orleans Rum produce notable quaffs. Richland Rum, in Georgia, started in 1999 and today makes rum from four different strains of sugarcane it tends on its own farm. It’s tasty, and would make colonials promptly reach for another.

AN UNDERGRADUATE DESIGN-BUILD PROGRAM of Auburn University’s School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture, Rural Studio represents a radical departure from the theoretical “paper architecture” taught in most schools. Based in the Hale County, Alabama, hamlet of Newbern (population 186), it was cofounded in 1993 by the late Samuel “Sambo” Mockbee and Dennis K. Ruth, and emphasizes socially conscious architecture and hands-on learning. Instructors and students design functional structures for the residents of Hale and surrounding counties, all part of the Black Belt, an impoverished western Alabama region known for its dark, fertile soil. Some of the best-known projects are in Mason’s Bend on the Black Warrior River.

Mockbee, a fifth-generation Mississippian, was a partner in a successful architecture firm when he decided to quit and start the Rural Studio with Ruth, his longtime friend and an Auburn architecture professor. What drove them was a belief that everyone—regardless of color, socioeconomic status, or education—deserves access to good design. Architects, they believed, have an ethical imperative to drive meaningful social and environmental change. They promoted the use of local materials and the arts of reusing, refurbishing, and recycling—especially if those kept costs down.

By 2017, the Rural Studio had completed more than 170 projects, including scores of houses, a public library, a community center, a Boys and Girls Club, a county bridge, public restrooms, and a new town hall for Newbern. Many of the program’s hundreds of alumni continue the work, creating a Rural Studio ripple effect across the South and beyond. “Architecture, more than any other art form, is a social art and must rest on the social and cultural base of its time and place,” Mockbee once said. And also: “Everyone, rich or poor, deserves a shelter for the soul.”

RUSSIAN TEA IS NOT FROM RUSSIA. AT least, not Russian Tea as Southerners know it. The giftable mixture of supermarket drink powders, the stuff of countless midcentury community cookbooks, dates back to the late 1800s and early 1900s, when American urbanites sipped black tea with lemon and sugar in imitation of upper-class Russians. (“Russian tea is not a special brand, but is the ordinary tea served with lemon instead of cream,” reported the Kinston, North Carolina, Daily Free Press in 1902. “Two lumps of sugar and a quarter of a lemon are placed on the saucer.”) Within decades, so-called Russian Tea, often doctored with clove and cinnamon, washed down chicken salad and mixed nuts at meetings of bridge clubs and church groups across the South. After World War II, the basic formula of hot tea with citrus evolved into a showcase for a bounty of space-age convenience foods: Tang, powdered lemonade, instant tea. And there, at last, is the Russian Tea many Southerners know and love—layered lovingly in a mason jar tastefully tied with grosgrain or gingham.

(1883–1973)

IF YOU COULD SET SOUTH CAROLINA’S LOWCOUNTRY to a spoken-word score, this would be the music: Archibald Rutledge’s deeply affecting stories of hounds and hunting, his rich poems about the icons of marsh and coastal wilderness, of Spanish moss and mourning whip-poor-wills and longleaf pine. Born in 1883 in McClellanville, Rutledge grew up at the famed Hampton Plantation, built in 1730, hangout of both George Washington and Francis “Swamp Fox” Marion. Steeped in the lore of the Lowcountry, he spent more than thirty years as a professor of English at a small Pennsylvania academy, then returned to his natal swamp woods in 1937 to reign for nearly four decades as the South’s most accomplished outdoor writer. He was South Carolina’s first poet laureate, publishing books of prose and poetry and even recording scores of poems for the Library of Congress. Deep River, published in 1960, was a Pulitzer finalist. Despite wide acclaim, Rutledge never shook loose of the ties to his childhood home. He died in 1973, in the little log cabin near Hampton Plantation where he was born.

RYE WHISKEY IS ONE OF THE FOUNDATIONAL American spirits. It was made chiefly from ryegrass, which distinguished it from liquor made from corn, wheat, or barley. It’s thought that the rise of rye followed the influx of immigrants from Ireland and Scotland who brought distilling techniques with them. Rather than using barley, which was common in their homelands, they chose rye, a hardier grass that provided good alcohol yields when fermented. Rye was produced in many frontier settlements, notably in western Pennsylvania and Maryland’s panhandle, and then all down the Appalachian Mountains. Production and consumption of it spread widely enough that when one comes upon references to whiskey in an early-nineteenth-century account in the South, the odds are it was rye. (Unless the account took place in Kentucky, which early on evinced a predilection for corn liquor.) It remained popular throughout the nineteenth century, but the Eastern rye industry never really recovered from the shutterings of Prohibition.

In the recent craft-spirits revival, though, rye has made a notable comeback. It’s now distilled everywhere from Mount Vernon—at a replica of George Washington’s distillery—to small distilleries throughout the South, including Catoctin Creek (Virginia), Corsair Distillery (Tennessee), and Thirteenth Colony Distilleries (Georgia). Major producers like Bulleit and Jim Beam have also stepped up their rye game.

I’VE LIVED IN NASHVILLE FOR MORE THAN forty-eight years, and I have had more religious experiences at the Ryman Auditorium than in all the churches in town combined. Which is saying a lot, since Nashville (so I’m told) has more churches per capita than any city on the planet.

My first Ryman experience happened my first night in Nashville. I had just turned eighteen and had come to town to look at Vanderbilt University. My parents had wanted me to go to Sweet Briar, Agnes Scott, or Hollins. They couldn’t understand my interest in Vanderbilt. But for me, it was simple. This was Nashville—Music City, U.S.A. When my student escort asked where I wanted to go that first night, I didn’t hesitate.

“I’d like to go to the Grand Ole Opry,” I said.

So off we went downtown, to the Ryman, where the Opry was based in those days. I remember this like it was yesterday: sitting in those hard pews, a large woman in front of us nursing a baby at her bare breast, somebody’s spilled Coke dripping from the balcony above, and Bobby Bare singing “Detroit City” while women flocked down the aisles flashing their Instamatics.

Ryman Auditorium is often hailed as one of America’s most historically significant music venues. Built in 1892 by a riverboat captain and businessman named Thomas G. Ryman, the late-Victorian Gothic Revival structure has served Nashville in several different capacities over the years. First, as the Union Gospel Tabernacle, it was a revival hall where people went to get “saved.” But after 1904, the year Thomas Ryman died, it became known forevermore as the Ryman Auditorium. With a seating capacity of over two thousand, it was for many years the largest indoor venue in Middle Tennessee. From 1904 to 1943, it became known as the Carnegie Hall of the South, a showcase for all sorts of attractions: the Metropolitan Opera, Enrico Caruso, Harry Houdini, Roy Rogers (with Trigger), Mae West, even Teddy Roosevelt. Meanwhile, a Nashville radio show featuring hillbilly music had become so popular that by 1943, it needed a larger venue. So from 1943 to 1974, the Ryman was home to the Grand Ole Opry. With its wooden pews and stained-glassed windows still intact, it became known as the Mother Church of Country Music.

During my freshman and sophomore years at Vanderbilt, a classmate named Woody Chrisman (aka Woody Paul, of the musical group Riders in the Sky) and I often hitchhiked downtown on weekend nights to the Ryman, where we invariably ended up in Roy Acuff’s dressing room. I remember scrambling up those steep backstage steps, carrying our instruments. Woody and Mr. Acuff would swap fiddle tunes, while Charlie Collins and I strummed along on our Martin guitars.

After the Opry moved to its new home in Opryland in 1974, the Ryman pretty much remained empty for the next two decades. Every now and then, I’d hear rumors that this landmark might succumb to the wrecking ball. But then, in 1994, an $8.5 million restoration saved the day. Since then, the Ryman has become a favorite stop for touring artists from all musical genres. Lucinda Williams, Lyle Lovett, Kris Kristofferson, Jerry Lee Lewis, John Hiatt, Bruce Springsteen (solo), the Reverend Al Green, Aretha Franklin, ZZ Top, and Dolly Parton are but a few of the acts I’ve caught there over the years. Religious experiences indeed.

And then, something happened that was bound to, sooner or later. In 1999, the Grand Ole Opry returned to the Ryman for its winter broadcasts. Fourteen years later—on November 26, 2013, to be exact—I played the Opry at the Ryman as a guest performer. I had played it a couple of times at the newer Grand Ole Opry House, but this was my first time to play it at the Ryman. As soon as I stepped on that stage, I felt the vibe. I couldn’t help it. It was surreal. All the ghosts of the ones who’d come before, I felt their presence. Johnny Cash kicking out the footlights. Hank Williams returning for a record six encores at his Opry debut in 1949. Minnie Pearl trembling with stage fright in the wings, Emmylou Harris dancing with Bill Monroe, and so on.

As I stood there soaking it all in, I looked out at the spot where I’d sat as a starry-eyed high-school senior watching Bobby Bare. I glanced up at the Confederate Gallery, where in 1971 I’d sat watching Neil Young and James Taylor during a live taping of The Johnny Cash Show. And the whole experience of what was and what had come before somehow lifted me up.

The Ryman is where souls get saved. Sometimes without their even knowing it.