FOR THE RECORD, ABSINTHE WILL NOT MAKE you hallucinate forest elves or slice off your ear. More than a century after the European spirit’s bohemian mystique begot a national panic in the United States, it isn’t even illegal anymore. A New Orleans environmental chemist named Ted Breaux brought an end to its stateside ban with a series of studies in the early 2000s. His conclusion: the Green Fairy doesn’t contain nearly enough toxic thujone—a by-product of one of its key ingredients, wormwood—to trigger hallucinations, and is therefore no more hazardous or morally degenerative than any other high-proof spirit. Sort of disappointing, no? But now, you can drink the herbal spirit as your ancestors did, free of gothic overtones. In the Crescent City, folks have long been fond of the slushy absinthe frappé—so fond that in 1934 they invented anise-flavored Herbsaint to replace the then banned base spirit. The flip side of the standard baroque spoon-and-sugar-cube method of absinthe drinking, the frappé, a blend of absinthe, soda water, and mint over crushed ice, is wonderfully refreshing on a clear summer day.

ACADIANS CAME TO BE KNOWN AS CAJUNS after they moved to Louisiana and lost a syllable or two. See Cajuns.

THE SOUTHERN ACCENT IS ONE OF OUR nation’s greatest treasures. Its beauty rivals that of a songbird or the most resonant cello. Had the Southern accent not been invented, our ears would have fallen off long ago, or become vestigial, fleshy cauliflowers hanging off the sides of our heads, for without the Southern accent there would have been nothing much worth listening to. Someone, somewhere, can make a case that I’m exaggerating its importance to us as a people and to America, but I can assure you I am not.

Maybe I am. But it’s lovely, isn’t it, the Southern accent? It’s not because I have one myself that I say this, because my accent is not what it could be: years of watching I Dream of Jeannie growing up have me talking more like an out-of-work B actor than like my grandmother Eva Pedigo, who came from Savannah, settled in Birmingham, and sounded as if she marinated her vowels in butter overnight.

An accent is your vocal personality. It’s like a hairstyle or a favorite pair of shoes, the only difference being that it’s in your throat. There’s a Northern accent as well, and it’s easily distinguishable from a Southern accent the same way a paper bag full of broken glass is distinguishable from a cashmere scarf. But when you leave the South and head in other directions, accents tend to disappear, the song of language is lost, and what you’re left with is bland communication, meaning without music.

It’s amusing, at least to me, to hear scholarly argot used to understand and investigate our day-to-day lives, especially the most resolutely nonscholarly subjects, like Southern English. My wife, a Vermonter, had no idea what fixin’ to meant when she first heard it. Had she researched the phrase, she would have learned that it indicated “immediate future action.” I could have told her that. A Southern drawl is vowel breaking; that’s what you call it if you’re in the language business. Vowels are broken into gliding vowels, making a one-syllable word like cat sound as if it might have two syllables (something like ca-yat). People not from the South say that sounds stupid, but I say I’m rubber and you’re glue, and anything you say bounces off me and sticks to you.

A Southern accent is not a single accent. There are many different Southern accents, some so distinct that an Alabama native like me will have no idea what that Carolinian might mean with the sounds coming out of his mouth. The Southern accent baseline is the merging of certain words—pen and pin, cot and caught. Why we talk the way we do is due to an ironic mélange of the speech of British immigrants in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and the Creole speech of African slaves. Today, believe it or not, Southern is the single most spoken accent in America. The rapidly growing number of Southern-accent speakers is due either to the fact that we’re having a lot more children down here than they are anywhere else, or the fact that we’re getting converts from Boston and New Jersey, seeking a better life. Probably both.

A WATERY WILDERNESS, THIS THREE-HUNDRED-THOUSAND-ACRE natural preserve lies just south of Charleston, South Carolina—a mix of public, private, and corporate holdings where the Ashepoo, Combahee, and Edisto (ACE) Rivers meet the sea.

The ACE was passed over by developers the first time around—too hard to get to. But after the build-out of the nearby Hilton Head, Seabrook, and Kiawah Islands, they took a long second look. Come 1988, there was a quiet but determined revolt to keep the ACE wild. Ted Turner, the Coors brewing family, and heirs of the publishing magnate R. R. Donnelley led the charge, assisted by the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Ducks Unlimited, and the Nature Conservancy. The upshot: private landowners would enjoy a considerable tax discount by not subdividing their properties and instead dedicating them to traditional uses, farming, logging, and hunting.

Though several state and county roads traverse the ACE Basin, you can reach most of it only by water. There are two dozen boat launches, several for kayaks only, and it lives up to its moniker: “One of the last great places.” But the ACE is also alligator central—keep your toes in the boat.

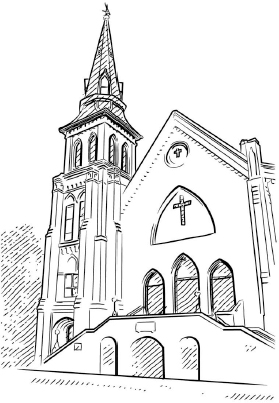

AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL (AME) CHURCH

CONSIDERING THAT AFRICAN AMERICANS were often barred from meeting together in the South before the Civil War, it’s no surprise that before emancipation, this religious sect—established in Philadelphia in 1816—spread largely in the North. Richard Allen, a former slave, formed the group after suffering racial discrimination at his local white Methodist Episcopal congregation. In the process, he founded the nation’s first independent black denomination.

After the war, Union army officials allowed clergy to come down and promote their beliefs to former slaves. The AME Church then experienced its largest period of growth, opening not only churches across the region but also thousands of schools, including Allen University in Columbia, South Carolina, and Morris Brown College in Atlanta.

The oldest congregation in the South, however, had begun worshipping years earlier in Charleston, South Carolina. The followers who would come to form “Mother” Emanuel AME, including the Reverend Morris Brown and Denmark Vesey, had quickly joined the tradition the same year as its founding up north. No stranger to tragedy—including the church’s being destroyed twice, once each by fire and earthquake, as well as Vesey’s execution for his part in planning a slave rebellion—Mother Emanuel once again captured the country’s attention in June 2015, when a twenty-one-year-old white supremacist shot and killed nine parishioners during a Bible study. In the immediate aftermath, the victims’ families expressed forgiveness toward the shooter, prompting a nationwide conversation about race and the removal of the Confederate flag from the grounds of the South Carolina State House in Columbia.

Today AME congregations are still predominantly African American, although all are welcome.

IF THE GOOD LORD HAD A HAND IN CREATING the quintessential Southern rock band, he (or she) couldn’t do any better than the Allman Brothers Band. Duane Allman and little brother Gregg were born in Nashville and later moved to Macon, Georgia, with fellow members Dickey Betts, Berry Oakley, Butch Trucks, and Jaimoe Johanson, eventually settling in at 2321 Vineville Avenue, aka the Big House, in 1970. Their self-titled debut and its follow-up, Idlewild South, were stiffs commercially, but the band had become dogged road warriors, playing some three hundred gigs a year with an improvisational energy fueled by family blood, booze, and copious amounts of drugs. In March 1971, they decided to record two nights in New York, and the resulting At Fillmore East became their breakthrough and remains one of the greatest live albums ever made, with searing versions of signature Allman tunes including “Hot ’Lanta,” “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” and an epic twenty-minute take on “Whipping Post.” Tragically, Duane and Berry Oakley were killed in motorcycle accidents in 1971 and 1972, respectively. The band soldiered on with various lineups—highlighted by guitarist Warren Haynes and Butch’s nephew Derek Trucks—packing venues for decades before finally calling it quits in 2014 with a final sold-out show at the Beacon Theatre in New York City. The Allmans detested the label “Southern rock” because they didn’t feel it took into account their love of jazz, soul, and country music, but every band in the genre that has come after, from Lynyrd Skynyrd to ZZ Top, owes them a debt.

THE MASTERS TOURNAMENT WAS ESTABLISHED in 1934 at Georgia’s Augusta National Golf Club by the Grand Slam winner—and bow-tied walking archetype of the Southern sportsman—Bobby Jones. But Augusta’s 11th, 12th, and 13th holes weren’t granted their lofty title, Amen Corner, until twenty-four years later, the year Arnold Palmer won his first green jacket. (Strictly speaking, the phrase describes the approach shot on 11, all of 12, and the tee shot on 13, but it has gradually come to refer to all three holes in their entirety.) The term is credited to the sportswriter Herbert Warren Wind, who, looking for a phrase akin to baseball’s “hot corner,” wrote in the April 21, 1958, issue of Sports Illustrated: “On the afternoon before the start of the recent Masters golf tournament, a wonderfully evocative ceremony took place at the farthest reach of the Augusta National Course—down in the Amen Corner where Rae’s Creek intersects the 13th fairway near the tee, then parallels the front edge of the green on the short 12th and finally swirls alongside the 11th green.” But the nickname didn’t entirely originate with Wind. He borrowed it from a jazz recording called “Shoutin’ in That Amen Corner,” which itself took the term from a New York City intersection frequented by lively Bible salesmen and preachers. At any rate, Wind’s appending the name to Augusta stuck. And the green jacket bequeathed to those who pray successfully through Amen Corner endures as one of the most instantly recognizable symbols of victory in all of sports.

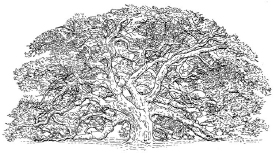

THE WORD MAJESTIC GETS TROTTED OUT OFTEN in descriptions of the South’s indigenous live oaks, but if ever a specimen deserved a breathless adjective, it’s South Carolina’s Angel Oak. Located off a dirt road on Johns Island, not far from Charleston proper, the tree looks like a character in a fairy tale (or a Tolkien fantasy) come to life—a wise and brooding presence. It’s thought to be four hundred to five hundred years old; its massive trunk measures 28 feet around, and it stands an imposing 66 1/2 feet tall. But the tree’s lateral reach is what boggles minds. Live oaks, built to withstand coastal winds, tend to have a branch span that greatly exceeds their height, and the Angel Oak’s gnarled and massive limbs, rising and curving and dipping, snake out in every direction—the longest reaching 187 feet from base to tip—and produce more than 17,000 square feet of shade. Perhaps there is a little magic in the oak’s embrace as well. Even during the height of segregation, black and white families picnicked under its cooling shadow in close proximity. After centuries in which neither hurricanes nor floods nor earthquakes could fell this living monument, development threatened to—until a dedicated group of locals and conservationists, in 2014, raised funds needed for the City of Charleston to purchase more than eighteen acres surrounding it. See Live Oak.

THIS SMALL HARBOR TOWN PERCHED ALONG Florida’s Panhandle coast is historic enough to have been the site of Native American settlements a few millennia ago, and more recently Spain, England, the Confederacy, and the Union took turns battling over it. It has been preserved enough to boast a main street and a waterfront that still look straight out of 1950s postcards, and the nearby pristine beaches are playgrounds of white-powder sand. But none of that is what starts Southerners’ mouths watering whenever they hear the town’s singsong name (locals refer to it simply as Apalach). It’s the oysters—the briny, impossibly plump bivalves for which Apalachicola is so revered. Historically, Apalachicola Bay has produced as much as 90 percent of the state’s harvest, and it’s the last place in the country where men and women still harvest wild oysters using only small boats and handheld tongs. Let the New Yorkers have their adorable little bluepoints. We’ll take a fat Apalachicola, on the half shell or a saltine with a dash of Tabasco.

GEOGRAPHY IS DESTINY. WHEN YOU ARE born, as I was, in the low beating heart of Appalachia, cosseted by the undulating green of the hollers, driving narrow strips of coiled roads that fall away on either side with the messy brutality of a severed limb, breathing damp, metallic air thick with the dust and fume of industry, you know your worth with firm certainty. Which is to say, not much.

Appalachia—which commonly counts swaths of North Carolina, Tennessee, Pennsylvania, and Kentucky, patches of Ohio, New York, Alabama, and Georgia, and every inch of West Virginia, my home state—can’t help but make a person feel small, what with her glorious ancientness and indifference on display in every corner.

A single look at her mountains, formed 480 million years ago and rubbed smooth by centuries, renders any mortal ambition petty by comparison. So realized is her beauty it borders on cruelty. So defined is her landscape you are forced to become a part of it—via mining her ground, or milling her lumber, or spinning plates from her river clay—if you aim to stay within it. There are no other choices. You either leave, or become subsumed.

Not that one can ever actually leave Appalachia. Her essence embeds in your soul like tar on fur, sticky and impossible to ignore, even if you hightail it to New York City and pretend you never knew what it felt like to walk barefoot over root-strewn alleys.

It’s enough to drive one mad, which is the other thing about Appalachia—we folks from there tend to have crazy in our blood. We aren’t shy about violence. (There are statistics on this. This is a thing you can look up.) Call it hillbilly pride, a wry self-deprecation married to itchy trigger fingers. We know who we are, but don’t you go trying to tell us.

Appalachia is a paradise of paradox: it makes you as it destroys you. And the people there follow suit, possessing deep wells of pride and humility, rage and tenderness. We love our stories, but we loathe pretending. We worship our mountains, even as we behead them. We praise the Lord, but more than half of us never attend church. We believe in haints, saints, and working-class heroes the rest of the world has forgotten. We play fiddles, not violins.

Appalachia is a breathtaking prison, and like all prisons, the confinement forges a gallows humor (seen clearly in our writers like James Agee, Jeanette Walls, and Breece D’J Pancake), and an unshakable mistrust of authority. Self-reliance breeds stubbornness, while self-awareness buoys the tendency to lead with our weaknesses and lampoon them into points of pride. Exhibit A: Dolly Parton. We taste our mortality on the regular—why not jump trains, or drink moonshine, or pick a fight, or howl at the moon, or get high, or love so hard our bones split?

Times are tough in Appalachia. Times have never not been tough in Appalachia. You feel alive there precisely because you never forget you are dying. Amid this fatalism survive hope, and fortitude, and fine, enduring music, and contortions of language so distinctive smarter people than we come and record the oldest of our voices, thinking them worthy of study. All the while the mountains sink deeper into history. And we along with them.

WHILE THE HABITAT OF ARMADILLOS RANGES from South America to the American South, the nine-banded armadillo, Dasypus novemcinctus, is the one found in the United States. Armadillo means “little armored one” in Spanish, referring to the armor covering its back, formed of plates of dermal bone covered in relatively small, overlapping epidermal scales called “scutes.” The Aztecs called armadillos ayotochtli, meaning “turtle-rabbit.” At least one Arkansan calls them “possum on the half shell.” The Texas legislature voted down repeated attempts to make the armadillo the state animal in the late 1970s, but in 1981 it achieved that status by executive decree. This is somewhat curious given that—while the animal has been a Texas souvenir since the 1890s—it is a known carrier of leprosy.

Burrowing, chiefly nocturnal, and solitary mammals, armadillos have few predators and are seldom eaten voluntarily by humans. One exception was during the Great Depression, when they were known as “Hoover hogs.” When startled, armadillos leap three or four feet straight into the air, as if spring-loaded. This evolutionary reflex has not served armadillos well on roads, since they often leap up and are killed by vehicles that would otherwise have left them unharmed. Along rural roads, it is common to find that someone has placed a beer can or bottle in the limbs of a dead armadillo. This is reprehensible but makes you think, however briefly, that it died happy.

(1901–1971)

AMERICA WAS BUILT WITH THE SWEAT and blood of millions of anonymous citizens, immigrants, and interlopers, but individuals whose names we will never forget authored the idea of America. Think of Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln, if you will, but America is more—much more—than its presidents. There is a long list of writers, artists, and musicians, without whom we wouldn’t be who we are. Near the top of that list—and not even necessarily alphabetically—is a man named Louis Armstrong.

Born in the first year of the twentieth century, in New Orleans, he had an early life that was as dark, desperate, and dismal as they come: He was abandoned by his father, his mother became a prostitute, and he had to leave school in fifth grade to collect junk and deliver coal. A little trouble with the law got him sent to the Colored Waif’s Home for Boys, where he learned how to play cornet and play it well (he didn’t play trumpet for years). By the time he was eighteen, he had married a prostitute himself and adopted a mentally disabled three-year-old boy named Clarence, whom he took care of for the rest of his life.

That paragraph alone could be turned into a novel—but there is so much more to come. His life deserves a quartet. It’s natural to flash forward and consider a man’s legacy, how Louis Armstrong became the most important influence on what we now think of as jazz, seeming to almost single-handedly create a new form of music. But, as with Elvis, who might be said to have done the same thing for rock and roll, there is a story behind the story that’s as fascinating as the story itself, because it’s our story, the story of America.

We know him as Satchmo, a nickname born of his very large mouth, which they said was as big as a satchel—the better to play trumpet with, my dear. He lived in New Orleans, Chicago, and New York City, and like heroes in the Grecian mode both triumphed and was beset by great misfortune. He invented scat singing; pop music became popular because of him. Then again, he had four wives and troubles with the mob, and in 1933 had to stop playing trumpet for a year because he played it so well he wore out his lips. He was the first African American to be featured in a Hollywood movie, the first to write an autobiography, and for decades the most famous African American in the world. Every time he was almost forgotten he came out with another song—“What a Wonderful World,” “Hello, Dolly”—that made him relevant again. Beboppers abandoned and rejected him, but he persevered, and behind that grand smile we learned he had a deep moral center.

Though he eventually settled up North, the South never left him; he took it with him everywhere. But he was also, and most of all, American. From a junk collector to a musical demigod: What’s more American than that?

THERE’S AN OLD JOKE IN ASHEVILLE THAT goes like this: “There are lots of jobs around here—a friend of mine has four of them.”

That sounds about right, whether it’s referring to a millworker who lives alongside a cold-water creek that bears his great-great-granddaddy’s name and who picks up taxidermy jobs to pay the bills, or a surrealist poet who moonlights in acupuncture and jewelry design. This mountain town has been scrappy and scruffy since its founding in 1784.

Mired in debt from the Depression through the 1980s, Asheville was too impoverished to tear down the art deco buildings that had arisen before fortunes faded, but it kept chugging along in the manner of the road-making machines that grandly bore through Beaucatcher Mountain in 1928. When tourists came back to town, those architectural marvels were right there waiting for them.

Tourism has been central to Asheville from the start: travelers praised the healing qualities of its clean air and hot springs even before European settlers showed up. Thomas Wolfe, who had Asheville in mind when he decreed that you can’t go home again, grew up in his mother’s boardinghouse there. The minor-league baseball team is officially named the Tourists.

The wealthy and well known have always flocked here. F. Scott Fitzgerald stayed at the Grove Park Inn to rest his lungs, wracked by tuberculosis, while his wife, Zelda, checked into a nearby hospital to rest her mind. Decades earlier, George Vanderbilt had chosen 130,000 acres of woods just south of town for his country estate, Biltmore, which is now one of the region’s biggest draws.

Visitors also gawk at the nightly drum circle, a quintessentially Asheville gathering that has steadily crescendoed from a few earnest sorts with bongos to a small colony of bohemians united in rhythm. It’s a modern-day successor to Shindig on the Green, a set of informal ballad sessions, old-time banjo strumming, and impromptu flatfooting that has taken place in a downtown park on Saturday nights for more than half a century.

Asheville is alive with music, and it suddenly has countless new venues in which the pickers can play. In addition to the boutiques, restaurants, bookstores, and artisan food shops that populate downtown, a slew of microbreweries backs up the city’s recent ascension as a craft-beer mecca. Oftentimes, you can find any given brewery’s taproom spotlighting music from a bunch of bearded guys this close to quitting every last one of their day jobs.

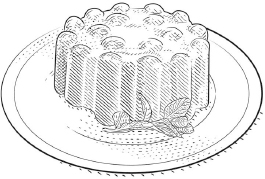

ONCE UPON A TIME, ASPIC, A DISH IN WHICH ingredients are set into a gelatinous mold, required a serious time commitment. Cooks extracted the necessary gelatin from hooves or bones over hours of simmering. Then came powdered gelatin, which democratized the jiggly centerpiece. By the turn of the twentieth century, sweet and savory aspics were making statements in cafeterias and at cocktail parties all over the country. Southerners served them at white-glove luncheons alongside deviled eggs and finger sandwiches. In places, we still do. Classic tomato aspic remains the house specialty at Gilchrist Drug in Mountain Brook, Alabama, which opened in 1928, and at the Colonnade Restaurant in Atlanta, dishing it up since 1927.

IT MIGHT NOT ENCAPSULATE ALL OF THE Cajun world, but “the Basin,” as locals call it, circumscribes the very heart and soul of Cajun Louisiana. It’s a swamp nearly twice the size of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, alive with crawfish, alligators, wild hogs, swamp deer, and black bears, fed by a river that’s not really a river. The Atchafalaya is a drain—a “distributary,” in geologic parlance—of the Mississippi River. At Simmesport, Louisiana, the Mississippi takes an eastward turn, spilling much of its high-water flow into the Atchafalaya. Unraveling into braided channels, bayous, and swamp lake chains, the Atchafalaya River then wends for some 140 miles, eventually draining into the Gulf of Mexico. But it’s hardly devoid of the hand of man. In 1876, South Louisiana’s vast swamp woods were sold off to pay for levee construction. Having just leveled the big timber of Michigan, logging companies turned to the Basin, snapping up cypress forest for as little as twenty-five cents per acre. Tree by tree, nearly the entire Atchafalaya Basin fell to the saw. Still, the swamp’s regrown forests are draped in Spanish moss and block out the Deep South sun. Hundreds of floating camps still draw Cajuns who hunt ducks, deer, and squirrels, and fish for crabs, catfish, bullfrogs, gaspergou, choupique, and buffalo fish. They cast their lines—and their hopes that the Basin’s future is as rich as its past.

S OUTHERN FOOTBALL FANS KNOW ATHENS as the home of the University of Georgia Bulldogs and the hallowed hedges of Sanford Stadium. Foodies are probably familiar with the chef Hugh Acheson, who helped kick off the city’s culinary cred with his restaurants 5&10 and The National. But there isn’t anybody in the country who hasn’t heard of a little band called R.E.M., which thrust this college town in the Georgia Piedmont to the forefront of the nation’s musical consciousness.

The story of Athens’s renown as a music incubator begins with a birthday party. On April 5, 1980, a UGA student named Kathleen O’Brien wanted her favorite local band—which had never played a real gig and was still nameless—to perform at the run-down St. Mary’s Episcopal church. Led by a charismatic front man—Michael Stipe—the group would soon adopt the moniker R.E.M. and go on to become one of the biggest bands in the world. Along with R.E.M., the town has produced a slew of national acts, including Widespread Panic, the Indigo Girls, and the Drive-By Truckers. But, why, oh why, sleepy Athens?

The seeds were planted in the 1970s: in 1972, the UGA college radio station WUOG began broadcasting, exerting an outsize influence on the music heard in town. Wuxtry Records founders Dan Wall and Mark Methe opened the now-iconic shop in 1976, and it quickly became a gathering place for area musicians. R.E.M. guitarist Peter Buck was working the counter when he met Michael Stipe, and they bonded over a mutual love of the Velvet Underground. Art-poppers the B-52s played their first gig at a Valentine’s Day party in 1977 before moving to New York and opening the door for other Athens bands like the seminal dance-rockers Pylon. Many of the town’s music scenesters attended art school at UGA, and the nearby downtown offered practice spaces such as Stitchcraft, where bands would gather in cinder-block rooms. Maybe someone brought in a case of beer or a couch. From there, they’d get gigs at the I&I Club, Tyrone’s O.C., and the 40 Watt, which after moving to several different locations found its permanent home at 285 W. Washington Street in 1991 and has become one of the country’s premier music clubs. For Stipe, the whole scene seemed like a happy accident. “We just kind of created our own thing and that’s part of the beauty of Athens,” he told Filter magazine in 2003, “that it’s so off the map and there’s no way you could ever be the East Village or an L.A. scene or a San Francisco scene, that it just became its own thing.”

For legions of Southern rock aficionados, though, perhaps the city’s most beloved product is the jam band extraordinaire Widespread Panic. Two of Panic’s founding members, John Bell and Michael Houser, met in a UGA dorm and picked up a couple of other musicians before starting out on the fraternity and bar circuit. And it was Panic that gave Athens its most crowded moment, when nearly a hundred thousand fans crammed onto city streets in 1998 to celebrate the release of the band’s first live CD, Light Fuse, Get Away.

LIKE SHIFTING PATTERNS IN A KALEIDOSCOPE, Atlanta defies one definition. One quarter turn here, and it’s the capital of the so-called New South, a transportation hub with sixteen Fortune 500 headquarters the likes of Home Depot and (of course) Coca-Cola, the planet’s busiest airport, and the innovative new BeltLine greenway transforming the inner city. Another turn, and it’s the seat of the civil rights movement, the “city too busy to hate” that produced Martin Luther King Jr., a thriving black middle and upper class, and the new Center for Civil and Human Rights. Keep turning, and you find a global melting pot with an international reputation burnished by the 1996 Olympic Games. The “A,” a hip-hop mecca that fostered TLC, Outkast, India. Arie, and T.I. A welcoming LGBT destination. A genteel “city in the forest” crisscrossed by any number of streets dubbed Peachtree. The “Hollywood of the South” that has beckoned the film industry with tax breaks, turning leafy lanes into postapocalyptic streetscapes for The Walking Dead. A patchwork quilt of thriving neighborhoods, from Cabbagetown to Virginia-Highland. A sprawling web of suburbs crawling with soccer moms.

The Atlanta metro area is each of these things, and all of these things at once. The multidimensional ability perhaps stems in no small part from its relatively new arrival. Founded in 1837—a century, give or take, after other centers of commerce such as Charlotte and Savannah—the railroad stop situated in the Appalachian foothills zipped through a couple of names (Marthasville, Terminus) before landing on its present one. Burned to a crisp by General William T. Sherman during the 1864 Battle of Atlanta, the city perhaps then took its phoenix spirit animal a little too literally, bulldozing over one thing or another over the years in the name of progress.

Now six million people call this North Georgia megalopolis home, and when you’re driving down 400 or around 285 past the new Atlanta Braves stadium or through the heart of the Connector on a Friday afternoon, it can feel like every single one of them is in his car and headed the same direction as you. Few are true natives of this transient city, but if you’re visiting, they’ll all probably tell you the same things, no matter how long ago they got here: the traffic is as bad as advertised. And don’t call it Hotlanta.

WHEN I WAS A KID IN NORTHERN ALABAMA, I spent a great deal of time with my grandparents Carthel and Louise Isbell. They lived next door to the school I attended from kindergarten through senior year, and since my parents couldn’t really afford day care, I spent my time learning to play guitar from my granddad or helping him tend to the farm animals he kept out back. They had VHS tapes of old Westerns, and we watched them at night, even though they’d seen them all at least a half dozen times. When I was seven, I started playing baseball for my local league (Dixie Youth, it was called). My grandparents made it to almost all my games. My grandfather would hand out two-dollar bills or ice cream sandwiches to my teammates and me afterward, while my grandmother would offer words of encouragement to the kids who hadn’t played so well, or the ones who were afraid of the ball.

Until I started playing baseball, my grandparents had very little experience with the game. But once they watched me play for a season or so, they had learned the rules and were hooked. They were very religious folks, didn’t curse or drink or watch R-rated movies, and other than old Westerns there was hardly anything on TV at night that we could all comfortably watch together. However, like pretty much everyone else in America in the eighties and nineties, we could watch Braves games on the Superstation.

I remember my grandmother’s excitement every time Rafael Belliard came on the screen. She liked him best because he always had a smile. My grandfather made up nicknames for almost all the Braves regulars. He called Bobby Cox “Wally Cox,” after the old TV comedian, and John Smoltz “Smokes” for obvious reasons.

We spent a lot of summer days and evenings watching those games. They were exciting for me even up into my angry teens, and my grandparents never had to worry about graphic violence or nudity or profanity or anything evil coming through the television into their peaceful little home. I was sixteen when Atlanta won the Series in ’95, and like a lot of sixteen-year-olds, I needed something to bring me closer to the elders in my family. Baseball, specifically Braves baseball, worked like a charm. For that, I will always be a fan.

YOU MAY HAVE HEARD THAT AUSTIN (with apologies to Brooklyn) is the coolest city on the planet. Or that Austin is dead, a sellout to shameless real estate developers and California tech-bro transplants. Austin, that haven for pinko potheads in a deeply conservative state, is also the new Dallas, the new Silicon Valley, the new Hollywood. Austin is the breakfast taco capital of the world (apologies to San Antonio) and the live-music capital, too (though aspiring musicians struggle to scratch out a living here anymore).

Austin is all of the above, of course, the relative weights depending largely on how long you’ve been here. If you read the comments sections online, God help you, the flourishing garden of skyscrapers downtown, soon to include the tallest residential building west of the Mississippi, is both a sign of the apocalypse (or at least the end of slacker heaven) and a beacon of good times and long nights.

The surest statement about Austin is that it’s a city in flux, though when the changes began is also a matter of debate. Was it in 1980, with the shuttering of the Armadillo World Headquarters, the legendary cavernous music venue in an old abandoned armory? Was it in the late nineties, when a software entrepreneur named Joe Liemandt, the founder of a company called Trilogy, lured a generation of tech kids to the city, a cohort that continues to drive much of its booming start-up scene? Was it in the late aughts, when South by Southwest’s Interactive conference ballooned to what’s now known, not always affectionately, as Geek Spring Break? Or maybe it’s all Dell’s fault, or Whole Foods’s. Does it matter?

Cities evolve. Austin, the country’s fastest growing, is a big-time boomtown, an international tourist destination, a lifestyle brand. The question is whether this new Austin still has its soul, whether it’s just a scruffy-chinned University of Texas kid all grown up with a big job and a nice house but who still holds, deep down, to that stoner free spirit. One measure is the output of its creative class, and on that one Austin can still bring it. How else to account for Aaron Franklin’s mastery of smoke and meat at Franklin Barbecue, which ignited a national fever for lowly brisket? Or Liz Lambert’s inspired boutique hotels (Hotel San José, Hotel Saint Cecilia), or Richard Linklater’s movies (Dazed and Confused, Slacker, Boyhood)? Another measure is traditions carrying on. Stevie Ray Vaughan is long gone, but here’s the new blues of Gary Clark Jr. A haze of weed smoke still fills the air above the swimming holes on Barton Creek on summer afternoons. Matthew McConaughey moved back. Willie, bless him, still throws his July Fourth picnic.

Where I live, along the old “hippie highway” that cuts through gentrifying South Austin, the forces of old and new coexist in what feels, for now at least, like balance. Every week another little bungalow or auto-body shop gets razed and replaced by something bigger and shinier. But one of our neighbors stills throws her rowdy full-moon parties in a crumbling barn that sits amid a row of angular modern homes, and the giant beer garden that sprouted next to the railroad tracks a couple of years ago is a draw for everyone.

In summer, we spend evenings around the pool at the High Road, a social club in a white midcentury building with peeling paint that used to be an Elks Lodge. Perched on a hill overlooking downtown, it sits on one of the best pieces of property in town. The club parted ways with the Elks when the organization tried to sell the building, and then the old-timers opened the membership to neighbors. The crowd is equal parts young families splashing in the water, tattooed hipsters smoking cigarettes, and ex-Elks lazing in the three-digit heat. As the sun sets and our new skyline shimmers violet, everyone orders another three-dollar beer and a neighbor plugs his guitar into an amp under the craggy canopy of live oaks. As one longtime local said to me recently, “How Old Austin is that?”

Very. And we will push forward and hang on to that through the next round of changes.

THIS IS THE MOST FAMOUS ISLAND YOU’VE probably never heard of, home to one of the signature flavors of the South. You can probably taste the inimitable Tabasco sauce in your sleep. It’s the frankincense and myrrh of the region, with roots, literally, sunk into a marshy South Louisiana salt dome called Avery Island. It was here that the first Capsicum frutescens peppers for Tabasco sauce were grown, and it’s here where every single Tabasco pepper plant is born today. While the demands of worldwide consumption now require peppers grown on small farms in countries from Honduras to Peru, and Zimbabwe to Zambia, the seeds for all those plants, each and every one, come from Avery Island. The McIlhenny family originally made the sauce in the late 1860s, marketing it in New Orleans groceries, and the company remains family owned and fills hundreds of thousands of bottles each day—the tail end of a long process. It takes five years to turn the seeds of Capsicum frutescens peppers and salt into Tabasco, fermented and aged in old wooden bourbon casks in a giant warehouse on Avery Island. Now sold in more than 180 countries, it’s a true synthesis of Southern culture. See Tabasco.