A FAMED NEW ORLEANS COFFEE SHOP, CAFÉ Du Monde opened in the French Market in 1862 not far from its current location just off Jackson Square. It’s best known for café au lait made with chicory, and beignets, which are puffy fried dough related in concept and etymology to the Spanish buñuelos. While some other ordering options exist (hot chocolate, for instance), coffee and beignets are pretty much what’s on offer.

Caffeine-deprived tourists often wait for an hour or longer for a seat at the French Quarter location (satellites exist in the suburbs and the New Orleans airport, but they lack the verve of the original). Therefore, a visit to Café Du Monde tends to be most successful when done opportunistically. That is, if you happen to pass by and see that it’s line-free, it’s advisable to walk in, sit down, and order coffee and beignets, even if you’re not in the least hungry.

Unless you are wearing black. Then under no circumstances should you visit Café Du Monde. The beignets are piled high with powdered sugar and bring to mind Colombian drug cartels; a single poorly executed bite will result in a small avalanche, leading to a streaked, smudgy garment that will mark one for the rest of the day as a rank amateur.

A CAJUN IS THE ULTIMATE SURVIVOR, SOMEONE who not only eats anything that doesn’t eat him first but also manages to make it taste good. In a fight, if you have a gun and he doesn’t, you’re still at a disadvantage. He will have at least three bateaux and an outdoor propane burner the size of an Atlas booster rocket in his yard for crawfish boils. Cajun derives from Acadia, the name of a French colony in northeastern Canada four hundred years ago. The Acadians refused to sign a loyalty oath, so the Brits kicked them out. Some rolled as far south as Louisiana, where they settled in the swamps and bayous that no one else wanted and did the work others wouldn’t. Not even the resident French people wanted anything to do with them. Set apart by language, culture, and customs, the Cajuns did what they do best: survive. After World War II, Cajuns became more integrated into the larger world. But only to a point. Today, for the most part, they can pass in the larger culture. The reverse is not true. Remember that. Classic Cajun story: Each Friday night, Boudreaux would torture his Catholic neighbors by grilling a tantalizing venison steak. In time, he agreed to convert. The priest sprinkled him with holy water, saying, “You were born a nonbeliever and raised a nonbeliever, but now you are a Catholic.” A week later, Boudreaux was once again grilling venison on Friday night. When the priest arrived, he found Boudreaux sprinkling water from a small bottle onto the meat and saying, “You was born a deer, you was raised a deer, but now you is a crawfish.”

MUCH LIKE THE EARLY SOUTHERN COLONISTS who cultivated these pink-, red-, and white-flowering shrubs, camellias are “from off.” Native to parts of China and Japan, the plants appeared in London in the early 1700s (and later the American colonies), courtesy of the East India Trading Company, when a bureaucratic goof resulted in a shipment of Camellia japonica rather than the expected Camellia sinensis (tea plants). A happy accident for Southerners from the eastern edge of Texas to the northern reaches of coastal Virginia, where the japonica thrived amid mild winters. The broad-leaved evergreens vary in size—they can grow as tall as thirty feet—as do their regal flowers, which range from feathery to almost perfectly symmetrical. Camellias prefer light shade, which protects them during hot summer months, and they bloom from October through April (even mid-May in places)—a reliable bright spot in winter gardens. Although the property takes its name from another Southern botanical darling, Magnolia Plantation and Gardens in Charleston, South Carolina, has the country’s largest camellia collection, with more than twenty thousand plants and a special focus on ancient varieties, including the world’s rarest—Middlemist’s Red.

AS THE STORY GOES, CHARLEY AND ELIZABETH Steen of Abbeville, Louisiana, founded their syrup company in 1910 as an effort to keep their cane crop from succumbing to frost. They purchased a mill to extract the juice, hitched it up to a mule, and were in business. More than a hundred years later, Steen’s, in its iconic bright yellow can, remains a familiar brand and serves as one of the last reliable producers of all-natural cane syrup—once a staple of the Louisiana pantry but now in danger of being Karo’ed and Aunt Jemima’ed out of the kitchen. Like any reduction of natural plant juices (sorghum, maple), the syrup takes on a dark color and a bit of earthy, caramel bitterness as the sweet extraction turns to treacle. But it has a twang all its own, a flavor that likes baked beans and barbecue sauce as well as it does biscuits and pancakes.

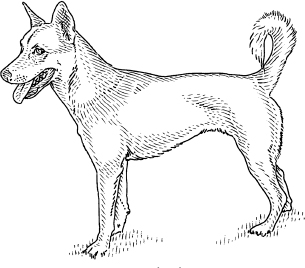

WHEN SOMEONE SAYS HIS DOG IS A “CAROLINA Dog,” the persistent assumption is that he means it’s a good ol’ mutt from the Carolinas. This drives owners crazy. Carolina Dogs are an honest-to-goodness breed. Recognized as such by the United Kennel Club only somewhat recently (in 1995), the Carolina Dog is known informally as the American dingo because, as with its Australian cousin, its natural habitat is the wild. Medium-sized and usually yellow (leading to another common nickname, Ol’ Yaller Dog), Carolina Dogs were “discovered” in the 1970s, when Dr. I. Lehr Brisbin Jr., an ecologist, spotted several of them roaming wild around the Savannah River. Noting their strong resemblance to the dingo, Brisbin began to investigate. Turns out Carolina Dogs, like dingoes, descended from the primitive dogs of Asia. Free-roaming mostly in the cypress swamps and longleaf pine forests of South Carolina and Georgia, Carolina Dogs are easily identified by their yellow coat, alert equilateral-triangle ears, and fishhook tail. They’re sometimes shy and often gentle, and generations of Ol’ Yaller Dog owners will assure you that they make great pets and have never been known to steal a baby.

IF YOU’VE EVER FOUND HOPPIN’ JOHN TO BE lacking, you’re not alone—and you’re most likely missing a key ingredient: Carolina Gold rice, the grain that built Charleston, South Carolina. It was the foundation for a series of canonical dishes: rice and peas, rice pudding, rice bread. Enslaved Africans from rice-growing regions raised great fortunes for planters, sowing and tending it in marshy coastal fields. Then came a flurry of social and economic upheavals: war, emancipation, destructive storms, new planting and harvesting technologies that favored firm soil over pluff mud. In 1911, a hurricane wiped out the last operation growing Carolina Gold. So the rice essentially vanished, all but forgotten on the compost pile of history, until 1985, when an eye surgeon named Richard Schulze wheedled a couple of sacks from a USDA seed bank for his Hardeeville, South Carolina, duck-hunting plantation. Schulze resurrected the firm, nutty grain and opened the floodgates to a wave of vocal advocates of this and other heirloom foods. Among them: the miller Glenn Roberts of Anson Mills in Columbia, South Carolina, and the heirloom-obsessed chef Sean Brock of Husk and McCrady’s restaurants in Charleston.

(1932–2003)

JOHNNY CASH ALWAYS WORE BLACK ONSTAGE, from his early days as an upstart pop star to his late-in-life revival as a grizzled elder statesman. But there were many shades to country music’s first outlaw. Although he famously performed for prisoners, he never actually served hard time himself. Dogged throughout his life by vice and addiction, he was also a man of deep religious conviction who ached to record simple gospel standards at the height of his stardom in the 1960s. A self-taught philosopher and poet, he once, in a drugged-up haze, carelessly started a fire that burned down five hundred acres of national forest and scared off forty-nine endangered condors. We all make mistakes, but his bleary-eyed deposition made sure that one went down in history: “I don’t care about your damn yellow buzzards,” he snarled. Cash’s openness about his flaws and his ongoing quest for redemption, though, made him one of the most human and beloved figures in modern music. Just after his wife, June Carter, passed away in 2003, the seventy-one-year-old got a call from Rick Rubin, the producer responsible for his popular late-in-life American albums. “Do you feel like somewhere you can find faith?” Rubin asked. Heartsick and ailing, Cash repeated a mantra that had seen him through a lifetime of joys and trials: “My faith is unshakable.” Although his eyesight was dwindling and his baritone was wearing thin, the son of Arkansas cotton farmers kept recording until just three weeks before his death later that year.

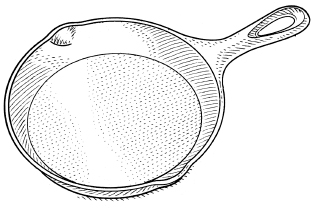

WHEN SORTING THROUGH FAMILY HEIRLOOMS, a savvy Southerner knows to always call dibs on that unassuming old cast-iron skillet, regardless of whether it has a perfectly smooth patina or looks like a rusty hunk of scrap. It may not flash the glitz of Grandmother’s silver, but it will sit on your stove top for decades ready to fry fish, bake cobbler, sear steak, sauté veggies, nail a frittata, caramelize onions, simmer a sauce—pretty much any cooking challenge you throw at it. An indestructible mash-up of iron and carbon, the skillet holds heat well and distributes it evenly (not to mention seriously works your biceps and forearms). Treated properly, it will outlive any of your other kitchen tools (and, truth be told, you). Cast-iron cookware originally came to the States with the colonists, and mass production in this country began more than a century ago in South Pittsburg, Tennessee, still the home of the iron cookware giant Lodge. You can easily clean a new, unrusted pan after each use: wash with warm water, dry completely, then rub it down with vegetable oil. Heat until it’s smoking, then leave it on your stove top until you need it—most likely at your next meal. If it needs more of a scrub, use a little salt and a paper towel to dislodge gunk before rinsing. Inherited a rust bucket? You’ll need to season it. Scour off the rust with steel wool, rub the pan down with vegetable oil, and place it upside-down in a 350°F oven for an hour.

THERE ARE A FEW SKILLS THAT MARK A CERTAIN elevated level of Southern sportsman, and the ability to hurl a cast net from the bow deck of a skiff is high on that list. It’s a circular net, its outer margins weighted with lead, and when thrown correctly, the centrifugal forces of those edge weights pull the net into a disk shape that hovers aloft before hitting the water, edges sinking while the net floats, thereby capturing shrimp, finger mullet, and pilchards that you’d otherwise have to lay down some cash for at the bait shop. Problem is, it ain’t easy to do, and when thrown incorrectly, a cast net wads up in midair, travels but half the distance you need, and crashes to the water as if you’ve hurled a sack of collards into the marsh, and you catch nothing but smirks of derision from all the real fishermen on the dock. Which explains why there are plenty of bait shops around.

CATFISH ARE NATIVE TO MOST OF THE eastern United States but, like magnolia trees—which they resemble in no other way—thrive best in the South. The three main species are channel cats, blue catfish, and flatheads. They can be caught on hook and line, in nets, or with “redstick” (dynamite, which can get you in legal trouble even if you don’t blow up the boat and your friends). The most sporting way is mano a pescado, also known as noodling, grabbing, or grabbling. I once went grabbling with some Mississippians on the Big Black River, in which they had sunk cypress boxes that the local flatheads liked to nest in. One man would block the entrance with his legs while another poked a six-foot steel trident inside. If there was a flathead home, you could hear it slamming against the box five feet down. Holding a fish stringer in one hand, you held on to the blocker’s legs to avoid being swept downstream and reached inside the box. For unknown reasons, a submerged catfish will often put up with a human fist in its mouth. Sometimes it won’t, “logrolling” with sufficient vigor to remove the skin from your forearm. What you’re trying to do is slip the stringer in its mouth and out a gill. You then wrap the cord around your wrist, hoping that the beast—mine was a fifty-pounder—won’t dislocate your shoulder. Then you pull him out and up, attempting to lift the fish clear of the water, thereby robbing it of its power. Meanwhile, everyone helpfully yells, “Get ’im up! Get ’im up, boy!” just in case you’ve forgotten what to do next. It’s tremendously exciting, and the kind of thing you later decide you really only need to do once.

CHARLESTONIANS HAVE LONG BEEN QUICK to tell you where their city lies on the map: at the point where the Cooper River meets the Ashley to form the Atlantic Ocean. That egocentric view has prevailed since 1663, when England’s King Charles II granted the region to a group of eight Lords Proprietors—headed by Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper—who built a fabulously lucrative empire of rice, cotton, and indigo. All of it was made possible by the labor of thousands of African slaves shipped in for just that purpose.

The fruits of this wealth ripened into a glorious little port city in which to live and stroll. Majestic homes of Colonial, Georgian, and Federal styles, wrapped with classic English gardens and nestled under giant canopies of magnolia and live oak, still define the residential neighborhood south of Broad Street. Above Broad, grand Greek Revival temples of government emphasized the society’s commitment to certain principles it believed hearkened back to Athens, namely a republic ruled by the oligarchy, and an intellectual and moral acceptance of slavery. Life was so good for rich Charlestonians that they barely joined the American Revolution. Not so the Civil War, the bloodiest in American history, which they famously started on April 12, 1861, when Confederate artillery fired on the Union garrison at Fort Sumter.

The next hundred years didn’t go so well for Charleston, which after the war eschewed the whole “New South” scheme adopted by coarser towns like Atlanta and Charlotte. The town withdrew into itself. Great antebellum homes fell into paint-chipped decline. The city boasted no hotels or restaurants worth the trip. Most visitors arrived on shore leave from U.S. Navy ships calling at the now-defunct naval base.

Then, simultaneously, came a couple of unrelated events that would change everything. In 1974, the Kuwaiti Investment Company purchased a barrier island full of timber just south of Charleston. It aimed to develop Kiawah Island into a gated oceanside golf community, as the developer Charles Fraser had done at Hilton Head Island just down the coast. One year later, Charlestonians elected as mayor a thirty-two-year-old real estate lawyer named Joe Riley, who had a vision for reviving the city’s struggling economy by restoring downtown to its former glory. As it turned out, Kiawah attracted well-heeled outsiders from all over the world who would fall in love with Riley’s theme park of the new, old American city. Between days at the beach and rounds of golf, they would stroll through town, marvel at its charm, muse about rehabbing a home where George Washington slept, and long for better restaurants.

Forty-some years later, it’s all come together, and Charleston is now recognized, by and large, as America’s Prom Queen. Condé Nast Traveler called it “America’s Most Friendly City.” Travel + Leisure raised that hand, declaring it “World’s Best City.” It’s where you travel to get married in the glorious spring. Or bring your buds for the bachelor or bachelorette party. Or honeymoon. Or take your family to the beach. Or bring your grandma for a historic walking tour. Or shoot ducks and catch redfish by day, then barhop Upper King Street by night. It’s where Bill Murray may drop by your table to nab a french fry. Where it’s still fashionable to take your family to church. New hotels and restaurants are popping up like dandelions. James Beard Awards fall from the sky on its chefs. Citadels like Husk and FIG and a few others have received worshipful national attention. Not long ago a neighborhood soul-food fixture, Bertha’s Kitchen, won a Beard America’s Classic award for its fried chicken, okra soup, and neck-bone fare. High time.

Warning: the dream could fade. People don’t just visit Charleston anymore. They move there, at the rate of thirty-five a day. With them come Atlanta-style apartments, traffic, a steady increase in horn blowing, and hedge-fund shoppers who buy $4 million teardowns (four-thousand-square-foot houses they bulldoze the day after closing) at the beach.

Hell, Scarlett, Rhett Butler would barely recognize the place.

THE REIGNING QUEEN OF JUNIOR LEAGUE cookbooks, first published in 1950. See Junior League.

THOMAS JEFFERSON WAS HERE. AND HERE. And over there. Indeed, sometimes it seems that ol’ T.J. never departed this town, that he’s still ambling between his imposing rotunda at the University of Virginia and Monticello, his tourist-magnet home atop a nearby mountain. But if he were still hanging around, he’d be wowed by so much more. He was a gourmand, after all, so would be astonished that a town of forty thousand can sustain such an impressive culinary scene, from the cherished neighborhood chicken joint Wayside Takeout to the special-occasion-worthy C&O Restaurant and its brethren—more chef-driven, farm-to-table eateries than you can shake a pastured pork belly at. Also quite the tippler, he no doubt would toast the area’s award-winning wineries (especially since he could never get his own vineyard to thrive), not to mention the newer wave of craft breweries and hard cideries. His intellectual curiosity and fondness for entertaining would be sated by Charlottesville’s shindig-a-week culture, including the Virginia Film Festival, the Foxfield steeplechase, and the always raucous bashes where the Charlottesville Lady Arm Wrestlers square off for charity. And like everyone else in town, he’d probably swear that he first saw the Dave Matthews Band back when it was playing parties on frat row, but now prefers any number of alt-folk acts that define today’s local music scene. Given Jefferson’s wondrous way with language, maybe he could even help coin a term to describe the undercurrent of energy that really makes Charlottesville hum—that certain friction between old money and disruptive technology, between townies and world citizens, between seersucker and blue collar, between academic idealism and rural pragmatism. Then again, maybe such intangibles are better left undefined, the better to let them continue morphing and shaping a random spot on the map into a unique place with a future that looks as striking as its history. So, Mr. Jefferson, how about we just grab a window seat at a downtown café for a while, local pint of Devils Backbone or Wild Wolf in hand, and revel in the people-watching paradise? Next round is on you.

(1923–)

LEAH CHASE WALKS BETWEEN RAINDROPS. Magic inhabits her domain. Though she’s not immune to the tragedies, disappointments, and failures that touch the rest of us, Leah manages to find . . . no, manufacture, a silver lining for whatever dark cloud comes her way.

An attempt at full disclosure: I consider Leah my adopted grandmother. I spent fourteen months “after the storm” in the confines of a Katrina trailer arguing with her about how best to reopen her restaurant. (Dooky Chase’s Restaurant first opened in New Orleans’ Tremé neighborhood in 1941, and those who have been served Leah’s Creole cooking range from Duke Ellington to Barack Obama to Thurgood Marshall to Ray Charles.) At times during our discussions, I stormed out; at other times, she said the conversation was through. We laughed. We cried. In those moments, I realized we were family. No words can do justice to my admiration and love for her and the legacy she has etched in the oyster-shell concrete of the streets of New Orleans. To describe what she means to the city’s sociopolitical, arts, and culture scenes in a few paragraphs is like trying to quickly sum up Martin Luther King Jr. or Gandhi or Lincoln: impossible. Leah Chase is New Orleans.

There is confidence in each measured syllable that emerges from her lips; she has a profound effect on people. She has scolded the city’s mayor for not having formal enough place settings for his office entertaining, and presidents for their table manners or for misusing Tabasco in her gumbo. She is a spirit unlike any other who has crossed my path.

An anecdote or two will have to suffice. In 2003, I got to spend a week cooking with her in Barbados. Each morning we had breakfast together, and for an hour I would quiz her over coffee—on characters from the civil rights era, sometimes, or black celebrities with whom she’d rubbed elbows. It soon dawned on me that I could not come up with a single person of influence whom she did not know and have an interesting story about. “Don’t get me started on that rascal Cab Calloway.” “Those marshals who ate breakfast with James Meredith at the restaurant every morning, while they were in New Orleans trying to get him in Ole Miss, could not have been any more kind.” “It’s a good thing Sugar Ray ate my chicken before that fight instead of a big ol’ steak down the street.” It was an eternal loop of fascination.

About eight years later, the Charleston, South Carolina, chef Sean Brock and I were traveling, separately, to New Orleans to meet up during his first visit to the city. As I sat in Atlanta-Hartsfield that afternoon, my phone rang. It was Sean, excited: he was on the ground in New Orleans, and where should he go for his first lunch? Get a cab, I told him without hesitation, and go get a table at Dooky Chase’s. Then go immediately to the kitchen to meet Ms. Leah. Tell her I sent you.

That was all I said. Sean is a rock; I have watched him sit steely-eyed across from Charlie Rose, trade intellectual punches with Anthony Bourdain and Heston Blumenthal. I wanted to see how the moment would strike him.

An hour and a half later, after my plane landed, Sean called again. He was laughing, but obviously through tears. “She hugged me, dude. . . . It was like meeting the pope. I literally don’t know what to do right now. I’m stunned.”

We caught up shortly afterward at a French Quarter bar. For an hour, Sean could say little more than, “You didn’t tell me I was going to cry.” And, “I just hope she remembers my name.”

Trust me on this: Get to Dooky Chase’s. Make your way to the kitchen. Spend a moment touching the hand of Leah Chase.

WHEN HE WAS IN SIXTH GRADE, A teacher asked Ishmael Reed to name the world’s highest mountain. “I didn’t even hesitate,” he wrote in his 1973 poetry collection, Chattanooga, “Lookout Mountain.”

Reed, later the recipient of a MacArthur “genius grant,” was a little off, of course. At 2,389 feet, Lookout is barely a blip on the topographical map. (There’s a building in Dubai more than 300 feet taller.) But that tree-spiked Tennessee prow has a certain prominence, a grip on the local psyche, and a long historical shadow. Lookout’s bluff once provided a perch for Confederate soldiers sniping at Union supply chains in order to starve away their enemies. For almost a century it has been home to perhaps our country’s most classic (and kitschy) triumvirate of natural wonders turned tourist draws (the Incline Railway, Rock City, and Ruby Falls). Lookout was one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s mountaintops from which, in his “I Have a Dream” speech, he hoped, throughout the nation, freedom would ring.

And Reed was right about this: “Chattanooga is something you / Can have anyway you want it.” The small Southern metropolis variegates and blossoms in any number of ways, although for Reed, a black man in a once deeply segregated city, there were thorns mixed in with the sweet. Chattanooga also once had the worst air quality in the country. It was all heavy industry and smokestacks, and the mountains trapped the pollution into a toxic pudding that filled up the valley, which for two decades emptied of those citizens who had the agency to leave.

But is this not the dominant story of the New South? How many nearby cities echo this exodus, and some similar, select resurrection?

Throughout the 1990s, a small army of ecominded entrepreneurs and visionary residents worked doggedly to transform their town from an industrial armpit into a global model for environmentally sound rejuvenation. Electric buses began carting people from downtown up the mountain. Razed factories sprouted into pedestrian parks and green space. Dilapidated mansions overlooking the river were reborn as the Bluff View Art District. Art is everywhere now, in fact, along with farm-to-table restaurants and fresh-brewed beer and the palpable buzz of possibility (accelerated by the country’s fastest Internet connections). Chattanooga, by most current standards, is verifiably cool.

There’s something more, though. A few years ago, on July 16, a date locals now know by its digits in the same way we’re all stamped with 9/11, a disturbed young man opened fire on a military recruiting center, wounding one, and then blazed into a nearby Navy and Marine Corps storefront, where he shot down five service members. The shooter had attended a local mosque. Researchers had just named Chattanooga the most “Bible-minded city” in America. Some might describe the situation as volatile, a powder keg with a freshly lit fuse.

Then this happened: people leaned in, Muslims and Christians, believers and non-believers, and began to listen, to grieve, to reconcile. By and large, the aftermath of a violent, religiously charged tragedy smack in the middle of a religiously charged epoch unwound in a peaceful and conciliatory manner. There is a plaque now, outside the building where those victims lost their lives, that says that instead of erupting in violence, the city prayed. “We did not lash out at easy targets for revenge,” it reads. “Instead, we invited each other into our lives, homes and places of worship.”

Chattanooga is something you can have any way you want it. A stopover for Northerners migrating south to Disney World. A mecca for rock climbers hunting toothy, chalk-marked boulder fields. A city healing over its wounds past and present, breathing fresher air, always looking toward what’s next.

OPEN A DRAWER IN ANY WELL-STOCKED Southern kitchen and you will find a cookie press, an industrial-looking steel extrusion tube with a lever and fitted dies. One could make fancy sugar cookies with these precision-engineered tools, but really the only action the gadgets generally see is for the production of cheese straws. These long, ridged wafers that look like bread sticks and taste infinitely richer are—axiomatically—the most beloved party snacks of all time. No one says no to a cheese straw. With scant variation to the recipe, the dough consists of copious amounts of grated sharp cheddar cheese mixed with soft butter. The cook works in just enough flour to set the short dough and adds an all-important pinch of cayenne pepper, which races through the straw like Tinker Bell through the forest, leaving a sparkle of bright spice. The Southern cheese straw is the very glory of what is dismissed as bridge party food.

IF CHICKEN AND WAFFLES WERE THE CUE IN A word association test, a healthy number of respondents would probably come back with Roscoe’s, the black-owned Los Angeles restaurant that’s been supplying syrupy plates of drumsticks, thighs, and buttered waffle rounds to celebrities since the 1970s. But the concept of combining fried chicken with waffles, instead of the biscuits that fast-food chains have designated poultry’s constant companions, originated half a world away in Germany. Creamed chicken and waffles was a popular dish there in the 1700s, when residents started boarding boats bound for America. They brought with them their chicken-and-waffle recipes, which survive in Pennsylvania Dutch cookbooks. Soon the dish was being served in wealthy Philadelphia homes, and the fad wended its way south, where plantation owners made it a centerpiece of their Sunday menus. After emancipation, African American cooks re-created the meal for their families, imprinting the memories that would inspire restaurateurs and jazz club owners in 1930s Harlem to offer it on their menus. One of their customers, Herb Hudson, went west to open Roscoe’s House of Chicken and Waffles.

MULL IS A BUTTERY STEW OF CHOPPED OR ground chicken thickened with milk, cream, and crackers, or a combination of two of those. Kin to burgoo, hash, and fish stew, it’s an iron-pot dish that often stars at church fund-raisers and other community get-togethers. Bear Grass, North Carolina, hosts an annual Chicken Mull Festival, and mull is also on the menu at barbecue joints around Athens, Georgia—and, passing as “chicken stew,” at Midway BBQ in Buffalo, South Carolina. Wherever you encounter it, be sure to shake a little hot sauce over the top before you spoon it up.

LIKE WAFFLE HOUSE, CHICK-FIL-A HAS A special resonance for Southerners, blending the modern American idea of industrialization with the timeless identity of the South. The family-owned business traces its roots not just to Baptists, but Southern Baptists. Its founder, S. Truett Cathy, was the sort of man who didn’t work Sundays, Christmas, or Thanksgiving, a tradition that continues in its more than 2,100 restaurants today. Cathy is considered the inventor of the fast-food chicken sandwich. He’d started running the Dwarf Grill in an Atlanta suburb in 1946. In 1961, after buying a shipment of chicken breasts deemed too large to be served as airline food—there was never much room on those little trays—he found that a pressure fryer could cook a boneless chicken sandwich as quickly as a fast-food hamburger. This changed the industry and led to the trademarked slogan, “We Didn’t Invent the Chicken, Just the Chicken Sandwich.” (The capitalized A in the name was meant to symbolize “Grade A” or “superior quality.”) The business juggernaut appeared to stumble when CEO Dan Cathy set off a public controversy in 2012, when he told a radio announcer that “. . . we are inviting God’s judgment on our nation when we shake our fist at Him and say, ‘We know better than you as to what constitutes a marriage.’” It was also revealed that the company had donated millions to Christian groups opposed to same-sex marriage. Many people boycotted Chick-fil-A. Counter-boycotts ensued. Within a month, however, the company issued a statement saying that it would henceforth leave the debate to “the government and political arena.” Then it got back to doing what it does best, turning out those sandwiches, nuggets, sweet tea, and waffle fries. By the way, every time a new restaurant opens, the first one hundred customers receive “a year’s worth” (fifty-two, to be precise) of free meals. A St. Petersburg, Florida, man, Richard Coley, has stood in line for the privilege at least 110 times.

AS THE OLD CHESTNUT GOES, THE BEST WAY to cook chitlins is outside—at someone else’s house. Pigs’ intestines aren’t a side dish for the faint of heart, and even if you can handle the concept, you might not be so amenable to the offal stink. They weren’t always so divisive, though. Both planters and the enslaved once valued chitlins before the modern era consigned them to the gallery of offal curiosities along with brains and lungs. Nowadays, they still surface at soul-food joints where cooks employ generations-old tricks to neutralize the odor. Soaking them in vinegar helps, and so does cooking them with potatoes and onions. At the table, you can smother them with hot sauce and slaw. Ultimately, though, chitlins are an acquired taste—centuries in the making.

(1936–2016)

COMING OFF THE TONGUE OF SOME OF ITS INHABITANTS, the pronunciation of Hale County, Alabama, can easily be mistaken for “Hell County.” And surely many have thought of it that way. It became a symbol to the world of deep Southern poverty after being documented in the 1941 book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. But while Walker Evans took the photographs for that volume as an outsider looking in, his future protégé—William Christenberry—came from Hale County itself. He began with pictures he took with a Brownie camera given to him as a child and developed the film at drugstores. His unpretentious straight-ahead photos of rural buildings and landscapes soon became some of the most celebrated works of photography in the twentieth century, helping to elevate color photography to the level of fine art. Returning to Hale County every year, Christenberry marked the passage of time by documenting the same buildings again and again—the door of his grandparents’ house, his uncle’s country store, a green warehouse. “I guess somebody would say I am literally obsessed with that landscape where I am from,” he once said. “I don’t really object to that. It is so ingrained in me. It is who I am. The place makes who you are.”

IN 1955, NEARLY A CENTURY AFTER APPOMATTOX, the writer Shelby Foote was just beginning work on what would become a massive three-volume history of the Civil War. In a letter to his friend Walker Percy, Foote spoke of being consumed by the story of the conflict. “I’m living a hermit’s life,” Foote told Percy. “Whiskey bores me. Movies are no damned good. The War is all.”

As it was for Foote, so it has long been for the American South. Note the capitalization: it wasn’t the “war” but the “War,” as if there had never been any other—a common enough view shared by many Southerners from Fort Sumter down to the present day. As Foote remarked, the “War” was the “crossroads of our being” not only as a region but as a nation. “It is an irrepressible conflict between opposing and enduring forces,” said the New York politician William H. Seward, “and it means that the United States must and will, sooner or later, become either entirely a slave-holding nation or entirely a free-labor nation.”

Seward’s observation came in 1858, but the origins of the conflict he believed inevitable stretched back to the beginnings of the American experiment in republican government. Slavery and its implications played essential roles in the American Revolution; it was only after the Virginia royal governor, Lord Dunmore, issued a proclamation offering freedom to those enslaved persons who joined the British in resisting colonial pressure in November 1775 that the whites of Virginia, a critical colony, united in their push for independence. A dozen years later, after military victory but a failed attempt at living under the Articles of Confederation, the framers of what became the Constitution wove concessions to the slave interest into the nature of the government, including a compromise providing that the enslaved be counted as three-fifths of a person for purposes of apportioning federal power, including the presidency of the United States. (Thomas Jefferson was derided as “the Negro President” since he owed his electoral majority to the slave states.) And forty years on from Philadelphia, Andrew Jackson faced down nullifiers in South Carolina over a tariff controversy that he knew was but prelude to a coming storm. “The tariff was only the pretext, and disunion and southern confederacy the real object,” Jackson said. “The next pretext will be the negro, or slavery question.”

Jackson was right. The expansion of American territory westward gave the ancient debate over slavery new force and urgency, and Abraham Lincoln’s refusal to allow what was euphemistically known as the “peculiar institution” to take root beyond the existing Southern states led to secession and war in the spring of 1861. The ensuing cataclysm was bloody and prolonged, claiming the lives of roughly 620,000 men. With the struggle came what Lincoln called a “new birth of freedom,” but only slowly. Despite emancipation and the passage of subsequent constitutional amendments, the South reverted to prewar form as soon as it practicably could, imposing Jim Crow laws to segregate a society that slavery had once defined.

Generations of white apologists would argue over the relative roles of slavery and “states’ rights” in the Civil War, but a fair-minded reading of history leads to the inescapable conclusion that the conflict was chiefly about race and white power. And while it is true that not every Southerner who fought consciously did so for slavery, the fight was nevertheless over the future of an old and discredited order.

The North fought a total war against the South, often treating civilian assets as combatant forces—a precursor of the nature of the world wars of the twentieth century. The vestiges of inequality, most vividly addressed during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s, can be traced to the events of 1861 through 1865 and beyond. And the politics of white nostalgia even into the twenty-first century are inextricably bound up with the “Lost Cause” mythology of the postwar period. “In that furnace (the War),” Foote told Percy in 1955, “they were shown up, every one, for what they were.” And so we are still, all these years distant.

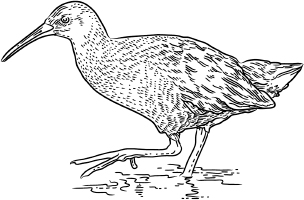

THE CLAPPER RAIL, OFTEN CALLED THE MARSH hen, is the most democratic of Southern game birds. Hunting wild quail generally requires owning a large plantation (or scoring an invite to one); shooting doves, a summer spent toiling over fields to grow rows of sunflowers and millet that attract the birds come fall. But the rail lives in the coastal environs of the Southeast, where its call—often described as the sound of a children’s wooden clapping toy—can be heard chattering across Lowcountry marshes. Hunters pursue rails from small boats that they can row or pole through the endless flooded acres of spartina grass during full- or new-moon tides. They are not known for blazing flight speed or for gustatory excellence on the table, but they inhabit some of the most beautiful environs in the country. And hunting them is a throwback to a simpler time. As one early devotee of the game bird once wrote to John James Audubon, “It gives variety to life; it is good exercise, and in all cases affords a capital dinner, besides the pleasure I feel when sending a mess of Marsh-hens to a friend such as you.”

(1898–1987)

THE LIST OF VOCABULARY WORDS THAT LEADS off a 1962 Citizenship School workbook hints at what Septima Clark aimed to accomplish by teaching African American adults across the South to read: arranged from A to Z, the entries include constitution, election, justice, knowledge, and rebellion. Within three years of Clark’s launching her first Citizenship School, designed to help black Southerners pass the literacy tests intended to disenfranchise them, the grassroots program had produced forty-two thousand new African American voters. As Myles Horton, founder of Tennessee’s Highlander Folk School, said, Clark “had as much to do with getting the civil rights movement started as anybody else.” Born in 1898 in Charleston, South Carolina, Clark attended Avery Normal School, the city’s first African American school. She took her first teaching job on nearby Johns Island, holding classes for adults at night. Clark joined Avery’s faculty in 1919 and taught taught at a handful of South Carolina schools for decades before being fired in 1956 for belonging to the NAACP, leading her to join the staff at Highlander; while there, she developed the Citizenship School, modeling it after her Johns Island sessions. Eventually, those schools were absorbed by the Southern Christian Leadership Council, which invested in the training of tens of thousands of volunteer teachers.

LOCATED IN ATLANTA, ON PONCE DE Leon, in the seedy basement of a now-shuttered motor lodge, the Clermont has been “alive since ’65.” Not much has changed.

Tattered velveteen paper clings to the walls amid band flyers and warnings from management not to bring cameras. No need, really. What you see will be seared into your eyes. Both a dance club and a club with dancers, the Clermont is an intimate smoke-filled shrine to raunch. The square footage is tight. The dance floor tighter still. If you plan to exhale, you will have to brush up against your fellow man. Or stripper. It’s like Delhi. With nudity.

Less a dive than a complete submersion, the Clermont is not clean. (If you drop something on the floor, best just to leave it, eyeglasses, wallets, and pants included.) Nor is it pretentious. The dancers feed their own quarters into the jukebox to perform. The cups are plastic. Cash only.

The performers, many middle-aged and up, look like real people. With real parts. If you want to be seen or meet the real estate agent of your dreams, best to head to any other bar in Atlanta. Unlike those so-called hot spots, the Clermont is inspiringly democratic. On any given night you will see college kids, hipsters, retirees, Navy SEALs, artists, stockbrokers. You will also see veteran dancer/poet Blondie crush a PBR can with her breasts. (Cash only.)

As with the best Southern haunts, continuity counts. Most of the dancers have been around for decades. Saturday’s disco night has been happening virtually since disco was a thing. Same DJ. Same bartenders. Same toilet shared with the talent, who more often than not chat you up and tell you how pretty you are, the way grandmothers are supposed to, except not naked.

Thing is, no one cares at the Clermont. About how you look. Or what you earn. Or the mistakes you’ve made. There is nothing you can do at the Clermont that 1) hasn’t been done and 2) will offend anyone in the joint. How many places can you say that about? Cover charge: free to ten dollars. Absolute abandon? Priceless.

(1932–1963)

IN 1957, NOT LONG AFTER VIRGINIA HENSLEY had parlayed performances on radio stations around her hometown of Winchester, Virginia, into a recording contract, the twenty-four-year-old appeared on Arthur Godfrey’s televised variety show. Producers insisted she trade her cowgirl getup for a cocktail gown and requested a song that didn’t twang as fiercely as the piece she had planned on playing. “Walking’ after Midnight” became an instant hit, charting with both country and pop listeners at a time when genres rarely mixed. Renamed Patsy Cline by a manager, Hensley went on to defang more taboos with her perfect pitch and husky voice, which she swore came from a childhood bout with rheumatic fever. Cline was the first woman to wear pants onstage at the Grand Ole Opry, and the only person ever to petition her way into the elite organization. She was the first female country singer to be billed above the men on her tour, and the first to perform at Carnegie Hall, an ideal setting for her polished Nashville sound. The definitive interpreter of “Crazy,” “Sweet Dreams,” and “She’s Got You” died at the age of thirty when the private plane flying her home from a benefit concert crashed in the West Tennessee woods.

IT MIGHT BE FORCING THE METAPHOR TO call John Pemberton and Asa Candler the Romulus and Remus of Atlanta. The city had been incorporated nearly forty years prior to Pemberton’s 1886 introduction of his soda-fountain beverage as a patent medicine, and Candler’s subsequent marketing and branding innovation that made icons of both the drink and its curvaceous bottle. But Atlanta’s personality—its distinctive admixture of small-town pride and global aspiration—started with Coca-Cola, still its best-known ambassador. You can’t go far without witnessing the imprint of the Candler family’s philanthropy and civic engagement. And you can’t leave without visiting the World of Coca-Cola, the ne plus ultra of corporate museums. This effervescent exhibit teaches you all you can ever know about Coke’s global presence, its advertising, and its misguided foray into New Coke. A massive tasting of global Coke brands sends you out on a sugar high.

THE OXFORD DICTIONARY OF ENGLISH NOTES that collards are “a cabbage of a variety that does not develop a heart,” which is somewhat harsh although not wholly inaccurate. See Greens.

KIN TO LOUISIANA RÉMOULADE AND THOUSAND Island dressing, comeback sauce originated at the Greek-owned Rotisserie restaurant in Jackson, Mississippi, in the 1930s. It spread quickly from there. Although the Rotisserie closed years ago, comeback remains a staple at nearby haunts like the Mayflower Café, Crechale’s, and Walker’s. It is an all-purpose special sauce, good for anything from salads to fresh shrimp to burgers to fried fish. Ingredients vary, but the basic components are mayonnaise, garlic, paprika, and chili sauce, and it’s now traveling far beyond Mississippi. Today you’ll find it on menus from Portland, Oregon, to New York City.

WHEN THE MICRONATION OF KEY WEST, Florida, proclaimed on April 23, 1982, that it had “seceded” from the United States, it chose the name the Conch Republic. (The government of the mother country, in turn, reacted with decades of silent indifference.) The rogue breakaway nation took its name from the big spiral-shelled sea snails commonly known as conchs (pronounced konks) or conches (konchez), which many a Floridian and Caribbean islander enthusiastically consumes. Because the dense meat of the snail is so tough, it typically gets beaten with a tenderizing hammer, cooked in a pressure cooker, and then minced or ground before anchoring such popular dishes as conch chowder, conch fritters, and conch ceviche. After cleaning, the shells can be turned into deep-resonating horns (years ago on Grenada, the man delivering ice used to blast a loud note from one to announce his arrival to island villagers). To this day, on the official Key West website, you can purchase a Conch Republic passport—a splendid conversation piece, although you probably shouldn’t rely on it to get you through airport security.

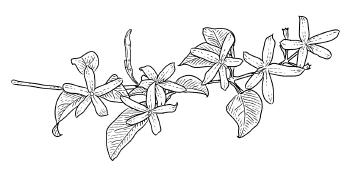

SO IT’S NATIVE TO ASIA AND NOT A TRUE relative of real-deal jasmine. Pah. The fragrant plant has snaked its way into the Southern consciousness in much the same way as those other Asian-born knockouts camellias and gardenias have. Stroll the streets of Charleston, South Carolina, come April and you’ll see foot-traffic jams of both residents and tourists snapping photos of archways, porch rails, mailboxes, and even entire potting sheds draped in the flowering vine. Tiny five-petal pinwheels bloom out from every inch of the dark green foliage in spring and early summer, and the aroma suggests a cross between nutmeg and the sultry summer evenings of your dreams. When the writer Eudora Welty became homesick for her Jackson, Mississippi, garden (as anyone transplanted up to the University of Wisconsin would have), she included a character in her thesis novella, Kin, who visits Mississippi and notes Southerners’ habit of enjoying one another’s gardens: “Bloom was everywhere in the streets, wistaria just ending, Confederate jasmine beginning. And down in the gardens! . . . Everybody grew some of the best of everybody else’s flowers.” Few Southerners would disagree: Confederate jasmine smells like home.

(1931–1964)

OTIS REDDING HAD THE BRAWN, AL GREEN had the slinkiness, but no one combined them better than Sam Cooke. His string of hits was a murderers’ row of chart toppers including “You Send Me,” “Chain Gang,” and “Twistin’ the Night Away.” In 1963, the Mississippi native’s infant son, Vincent, drowned in the swimming pool at the Cooke family home in Los Angeles. Cooke was devastated, and in the tragedy’s aftermath he shifted his focus from romantic love songs to something more impactful and profound. He had also become obsessed with Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” confiding to friends and relatives that he felt a black man should have written the song. Cooke eventually tried to do Dylan one better. In late 1963, he entered an L.A. recording studio and recorded the soaring, socially charged “A Change Is Gonna Come,” released after his death and arguably the greatest soul song ever recorded, one that laid the groundwork for other politically minded singers including Marvin Gaye and Curtis Mayfield.

THE COON DOG CEMETERY IS ON A GENTLY sloping rise in the Freedom Hills of North Alabama, prolific with hardwoods—elm, oak, ash—and pine trees too, but with enough open space left over to walk between them, even with a dog. The rise falls like a slide into a holler, thickly wooded and dark. Way back when, at certain times of the day when the sun cut through the treetops, there was a winking glint off a moonshiner’s still. Beyond that nothing but green, an ocean of forest, and all the critters you’d expect to find there: the barred owl, kestrels, fox squirrels, deer. Raccoon.

In 1937, Key Underwood buried his dog, a coonhound, here, because this is a place they loved to hunt. The dog’s name was Troop, and he carved that name into a chunk of sandstone from the chimney of an old cabin with a screwdriver and a hammer, and below that the essential information, the only indisputable facts of existence: the day he was born and the day he died.

4-1-22

9-4-37

This is what was happening in September 1937 on a mountaintop in Cherokee, Alabama. Since then, more than three hundred dogs have been buried here. And not just any dogs: they are, each and every one of them, coonhounds. Redbone, black-and-tan, English bluetick, English redtick, Plott, Treeing Walker, and various combinations of the above. It’s a place that’s known as—well, what else could it be known as?—the Coon Dog Cemetery (officially the Key Underwood Coon Dog Memorial Graveyard), and there is no place like it anywhere in the world. One of the best places on the planet, I think, so peaceful, the spirits of dogs who lived their fullest lives lingering there, wind blowing through the oaks, you can almost hear them howl.

In some respects, the Coon Dog Cemetery looks a lot like other cemeteries in which there are not coon dogs. Traditional rectangular sandstone gravestones are inscribed with names, dates, and sometimes a pithy remembrance: “He wasn’t the best, but he was the best I ever had,” or simply “In Loving Memory.” But there is more than one way to mark a grave, and in the Coon Dog Cemetery you might could see them all. Some are just pieces of wood or rocks, or combinations of both; one looks like the other side of a car tag, one a small piece of a wrought-iron fence, and one—“Bear”—a rusting piece of soldered metal on a pole.

The Coon Dog Cemetery has its own road—Coon Dog Cemetery Road—a ten-mile-long stretch of winding rolling beauty, a barely paved one-and-a-half-lane road with steep hills and sharp curves sketched through a thousand acres of nothing much. You’re never going to get there without going there, because it’s not on the way to anywhere else. That said, the space here feels more sequestered than it does isolated. I won’t call it holy, because that’s a big word that brings a lot of baggage with it. But hallowed? Sure. It’s a hallowed spot. A place like this shouldn’t be too close to anything else. It’s one of those places you wish you couldn’t find with a GPS.

THE SIMPLEST DISH IN THE WHOLE SOUTH IS pinto beans, simmered with lard and paired with cornbread, just as it’s served at the Bean Barn in Greeneville, Tennessee. Then again, maybe the humblest of them all is crumblin’, the Texan term for a tall glass of buttermilk with cornbread broken into it, the way the onetime Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn liked it. Or perhaps it’s a mess of vinegary South Carolina greens, with a thin sliver of cornbread alongside. Starting to detect a pattern? Cornbread, affordable and pleasing, defines Southern cuisine from one end of the region to the other. Eaters of European and African ancestry were latecomers to the dish, of course: Native Americans had been cooking with corn for thousands of years when they arrived. Europeans were initially unimpressed, comparing corn pone unfavorably with fluffy wheat breads. They ultimately decided that dense cakes cooked in ash were preferable to starvation, and corn crept into their diets. Benjamin Franklin was an early cornbread champion, calling johnnycakes a sight better than Yorkshire muffins. But Southerners grew especially fond of ground cornmeal, which they ate until after the Civil War without the embellishments of eggs, butter, and milk. Many cornbread fans prefer it that way still.

AT THE 1963 NEWPORT FOLK FESTIVAL IN Rhode Island, a seventy-some-year-old man known as Mississippi John Hurt spellbound the crowds with his fingerpicking guitar style and his Delta blues and field ballads—and then returned home to Avalon, Mississippi, where he had long worked as a sharecropper, to pick cotton for four dollars a day. His fellow bluesman Lead Belly famously sang that when he was “a little baby, my mother rocked me in the cradle, In them ole cotton fields back home” (in his folk classic “Cotton Fields,” which has been covered by everyone from Elvis Presley to Johnny Cash to Creedence Clearwater Revival to—go figure—the Beach Boys). Cotton is indelibly woven into the South’s past and its present. There’s no excusing the commodity’s dark past—its planters were among those who perpetuated slavery, and the crop begot the “King Cotton” rationale for secession and later tethered sharecroppers to bottomless debt. There’s also no dismissing its enduring status as an economic engine; even now, cotton clothes the world, and the United States exports more of it than any other country. Drive through most any state below the Mason-Dixon—especially Texas, Georgia, Mississippi, or Alabama—and it’s not hard to find seas of white bolls. Nowadays, much like Southern foodways, Southern cotton has begun to tilt toward the local and artisanal; witness the locally milled denim revival in North Carolina, for instance, and the artist collective Alabama Chanin’s insistence on growing and harvesting its own organic varieties. For better and for worse, it’s hard to find a Southern narrative that doesn’t have cotton threads running through it.

BRITISH SEAFARERS BROUGHT NOT ONLY Indian spices but also a recipe for this simple chicken curry dish to the port of Savannah. While versions of it appear in both the United Kingdom and India, it has taken on a special Lowcountry flavor, and today there’s nary a community cookbook in Savannah or nearby Charleston without a recipe. Pieces of bone-in chicken simmer until tender with tomatoes, onions, dried currants, and the gentlest possible hit of curry powder. The chicken and its thin sauce get ladled over the kind of fluffy white rice that has long gone out of style, and diners pass garnishes that must include crumbled bacon, chopped parsley, and toasted almonds or peanuts. Though few cooks turn up the heat on the curry, many like rococo flourishes for garnish, including toasted coconut, sieved hard-boiled egg, fried onions, and mango chutney. But as with any oft-reproduced canonical recipe, the variations are tiny but endless.

COUNTRY HAM IS THE COMMON NAME FOR the dry-cured hind leg of a pig. Born out of hardscrabble necessity, perfected over centuries, this salty delicacy has long been the pride of the Southern table. Whether skillet fried in redeye gravy for breakfast, boiled and slipped into buttermilk biscuits on Christmas Eve, or shaved dry and served alongside figs and cheese in a Michelin-star restaurant, country ham can go high or low. Its appeal is universal, cutting across racial and class divisions. Patrick Martins, founder of Heritage Foods USA, calls country ham “one of the South’s most important contributions to the American table.”

Country ham is as old as the South itself. British colonists brought hogs to Jamestown along with the old-world know-how to salt-cure their flesh. Pioneers pushing west survived on boiled bear and deer meat until they could establish a herd of swine. Frontier hogs were mostly feral and fleet of foot. Settlers rounded them up each fall during the first extended cold spell, killing some and capturing others to fatten on corn.

As the South became more established, the region’s hogs grew tamer and rounder, but the seasonal rhythms of the smokehouse remained the same. After the autumn slaughter, hams (and shoulders, jowls, and bacon) were packed in salt for four to six weeks, hung in a smokehouse for weeks to keep away spring flies, and left hanging through the hot months to sweat out the last drops of moisture. Conditions are best in a swath of the South—Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky—that falls within the world’s ham belt, a distinct climatic zone where temperatures get neither too cold nor too hot.

A country ham is more precious today than ever before because dry-curing is no longer a necessity. But the slow-cured ham tastes better thanks to the salt, the earthy hickory smoke, and the twang of proteins left to break down over time by natural enzymes. Hams by legendary cure masters—Broadbent, Benton, Edwards—stand hock to hock with the great dry-cured hams of Spain and Italy. See Cure masters; Benton, Allan.

CRACKER IS ONE OF THOSE POWDER-KEG words that can sound harmless when bandied by a friend, or blow up big-time if mumbled by a stranger to imply that someone is uneducated, backwoods, or otherwise overly fond of his cousins. In Florida, however, the term offers distinctive shades of meaning and is often deployed with a sense of ironic pride. Back in the 1800s, the term cracker cowboy was coined to describe frontiersmen who, unlike their Western counterparts, used dogs and whips to round up cattle scattered over the state’s vast, untamed scrublands. The famed artist Frederic Remington even sketched some classic images of these hardworking, hard-drinking souls in 1895, though he lamented their lack of lassos. Nowadays, some Floridians use cracker cowboy or Florida cracker to claim descent from these long-ago settlers, as opposed to the waves of newcomers who migrated to the Sunshine State after World War II (and, more to the point, after the invention of air-conditioning). The term has even been normalized enough to be lent to the Cracker Trail Annual Cross-State Ride, a heritage-honoring event held near Bradenton every February. You know—just in time for all the snowbirds from New York to saddle up, too.

ANYWHERE THAT PEOPLE RENDER LARD, they make cracklings. As the white fat liquefies, bits of fatty tissue brown and rise to the surface, ready to scoop out. Skinless cracklings can emerge from the hot grease as puffy and crumbly as Cheez Doodles, while those with the rinds still on pack a powerful head-ringing crunch. Most people eat them out of hand, or crumble them into cornbread, where they form pockets of savory, porky goodness. There is one important regional variation. If you buy a bag of cracklings in Louisiana, you will end up snacking on chunks of fried pork belly, with streaks of meat to wash down all that tasty fat and crunchy rind. Sometimes called grattons in Cajun country, these cracklings are often sold alongside and consumed with boudin.

AFFECTIONATELY KNOWN AS MUDBUGS OR crawdaddies in the South, and formally as crayfish in the British Isles and the New York Times, these freshwater crustaceans are treasured for their lobster-like flavor and appearance. Procambarus clarkii, or red swamp crawfish, is the species harvested wild by the Cajun natives of western Louisiana’s Atchafalaya Swamp; they are especially abundant during the flood stages that occur between late winter and early summer.

Cajun-style crawfish are typically boiled in a spicy stock with small potatoes and corn on the cob, then dumped on a picnic table spread with newspapers. At community events called crawfish boils, diners assemble their own plates by reaching into the help-yourself heap. Restaurants called boiling points sell cooked crawfish by the pound. Along the Gulf coast, waterfront crab shacks now offer freshwater crawfish on the “seafood” menu. Seafood experts suggest that increasingly scarce Gulf crabs are being replaced by abundant crawfish, which are now available farm raised as well as wild.

Beginning around 2001, Vietnamese-owned restaurants in Houston and elsewhere with names like Cajun Kitchen and Cajun Corner opened, largely drawing clients of Southeast Asian descent and ushering in a new style of Asian-Cajun crawfish. Cooks spike the boiling pot with Asian lemongrass and ginger, and the crawfish appear at the table in a plastic bag, swimming in garlic butter or spicy sauce. More mouthwatering globalism: a few years ago, a Vietnamese American woman opened a place called the Cajun Cua in Saigon. She calls it a Vayjun restaurant. See Cajuns.

THE CREEPING FIG—FICUS PUMILA, ALSO known as the climbing fig—grows across the South. Its tiny, oblong, heart-shaped leaves and vines wrap around wrought-iron gates, stencil the facades of brick houses, and bring lacy patterns to concrete garden walls. Like many Southerners, this evergreen member of the mulberry family doesn’t fare well in cold temperatures, but it can withstand saltwater spray from Virginia to Florida and the scorching sun of the Gulf states. Once you’ve planted it, let creeping fig climb wildly, but keep your pruning shears handy—left to its own devices, the feisty ficus will embrace everything it can wrap its tendrils around, and has been known to inflict damage on stucco and wooden structures as it’s removed. Creeping fig requires no trellis to climb; it always finds a way to make a home its own.

CREOLE IS A SHAPE-SHIFTY TERM THAT HAS meant different things to different generations since the early 1700s, most notably in New Orleans. “The slippery nature of this term continues to produce confusions, controversies, and conflicts in New Orleans,” the historian Rien Fertel has written. “. . . Its ‘meaning differs according to location, as it does with historical period and from one [scholarly] discipline to another.’”

Creole initially described someone who had been born in the colonies, differentiating him or her from a neighbor who may have been born in France or Spain and subsequently immigrated. This definition wavered as more Creoles populated the city, and the word instead came to mean chiefly those who identified as being of French or Spanish descent, and usually practicing Catholicism. This was a point of status for those who did not want to be confused with barbaric Americans. After the Civil War, the term came to be more loosely applied to African Americans, often of mixed race, whose ancestors had arrived with the French or Spanish settlers (sometimes as slaves, sometimes as freemen) and who identified with old-world culture rather than the culture of newly freed American slaves.

Today people often use the term culinarily to describe a cuisine linked to French culture (cream sauces, lots of butter). This is not to be confused with Cajun cooking, which is distinct and plagued by its own confusions, controversies, and conflicts.

THE MISSISSIPPI DELTA INTERSECTION WHERE bluesman Robert Johnson made his deal with the devil (or so the story goes). See Johnson, Robert.

THIS, TILL THE DAY I DIE, IS WHAT FLORIDA tastes like.

Old Cuba, it is said, gave birth to it, in the cigar factories and sugar mills, and sent it across the waters by sail and steam, to Ybor City and Key West, then, after Castro, to Miami, but you will play hell getting Miamians to say it did not belong to them all along.

People will fight you over a Cuban sandwich. They will shout you down over who invented it, who perfected it, who has the best one now, and what the traditional ingredients should be. To tinker with it too much is like painting a mustache on the Mona Lisa. It is best, being an interloper, to be neutral, or try to be.

I could not be more neutral. I fell in love with the Cuban sandwich in territorial waters, watching the shallows for sharks and rays, sacrificing baitfish to the trout, and ladyfish, and now and then a mangrove snapper. But if I was going to be honest, I’d have to say that I was mostly waiting for lunch. I knew that, when the sun looked right to him, the boat’s captain, Joe Romeo, would nod to me, the dead weight, and ask me if I was hungry. He would hand me an ice-cold Coca-Cola from the chest; I am far too poor a fisherman, and seaman, to even consider fishing drunk, and since I would have made two of Joe, I am certain he would have been unable to hoist me back into the vessel if I had fallen out, and it was too far to swim or wade back to Anna Maria Island.

Then he would toss me lunch. This time, it was a foot-long foil-wrapped parcel that had been ruminating on the deck since dawn, a beautifully simple sandwich of roast pork, sweet ham, Swiss cheese, and pickles on buttered Cuban bread dressed in only a little mustard, then heated through in a sandwich press till the cheese melted and the crusty bread was flat and crispy. It was the perfect thing to keep warm on the deck.

The fine Florida writer Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings wrote once that a cold biscuit in the woods is better than cake indoors, and it may be that it is the same on the water. I remember, once, seeing a hammerhead glide across the sand in water no deeper than my thigh. What restaurant, in any land, has that view?

I took a bite of that sandwich and, in that place and moment, was convinced it was the best thing I ever ate.

A year or so later I moved to Miami, which was a little like finding heaven on the other end of the Tamiami Trail. In every Cuban restaurant, market, and quite a few gas stations, you could find a good Cuban sandwich, but when I made the mistake of telling people I had come from across the state, they had to set me straight.

“That’s not a real Cuban,” people sniffed.

“Why?” I asked.

It had to do with salami. When the cigar factories migrated from Key West to Ybor City in the late 1800s, thousands of Cubans moved to Tampa, and Ybor City in particular. A strong Italian influence, it is believed, also influenced the sandwich.

“They put salami on them,” an old Miamian told me, and made a face.

That, it was explained to me, made the west coast’s claim to the sandwich null and void.

Miami did not claim the sandwich so much as conquer it. On Calle Ocho, on Coral Way, on every paved road, I found delicious Cubanos, and my favorite meal quickly became a sandwich and a café con leche, preferably eaten in a cool place on a hot day, reading a Miami Herald or a St. Petersburg Times, people-watching, wondering if a slice of tres leches might make life just too good to bear.

This Cuban, the Miami Cuban, was the true Cuban, I was lectured, but I remained neutral, having no dog in this fight.

Instead, I wandered off to try to write stuff, about something, and wait till another lunch, which had a pretty good chance of being a Cuban sandwich, unless I had my mouth set for a grouper sandwich, or some black bean soup with ham croquetas and sweet plantains. Because, deep in my heart, I knew I would leave this place someday, and that outside Florida it would not be the same.

I read that at least one Cuban sandwich emporium will make you a traditional Cubano with a ham croqueta on it. I would be willing to risk a fistfight to get one of them.

IN PRINCETON, KENTUCKY, NANCY NEWSOM Mahaffey of Col. Bill Newsom’s Aged Kentucky Country Ham cures haunches the same way her family has since the 1600s. Each winter, she packs them in salt, then smokes them over nineteenth-century iron kettles. At the end of each summer, she releases another year’s batch. Mahaffey is a purist, but she isn’t alone in her painstaking old-fashioned approach. Allan Benton of Benton’s Smoky Mountain Country Hams, in Madisonville, Tennessee, learned to cure hams in a log smokehouse on his grandparents’ property in Scott County, Virginia. Along the Virginia coast, Sam Edwards III carries on a tradition that dates back to the earliest days of the republic at Edwards Virginia Smokehouse in Surry. Lately, our homegrown cousin to prosciutto has undergone a renaissance. Cure masters who’ve held on to this labor-intensive tradition over the years have become national celebrities. Having persevered through thankless decades, though, none of them are in it for the glory. Southern country ham producers do what it takes to keep a tradition on the table. Here’s how to honor them: vow never to overcook their product; all it needs is a quick sear on each side. Shaved thin, it requires no cooking at all. See Benton, Allan; Country ham.

COTTON FARMER, TOWNSMAN, OR TRANSPLANTED Atlanta-based victim of sprawl trapped in a split-level overlooking I-85, any given Southerner’s relationship with the land is the gift that keeps on giving to the language. Southerners have an easy command of what a covey of quail does on the rise, how to hot-walk a horse, or what a copperhead lounging out back under the blackberry bushes can do if you poke it with a stick. The bounty of flora and fauna and their behavior only expand the field of wordplay. When Southerners speak editorially of their fellow citizens, even the most basic agrarian similes—she’s common as pig tracks, or he’s crooked as a dog’s hind leg—can be used to great effect.

When more forceful comparison is required, a Southerner undisturbed in his natural habitat will resort to the known, and technically profane, classics. These beloved old tools have been handed down in a treasure chest of expression from all ancestral streams that fed the mother tongue, namely, Latin, Saxon German, Norman French, and Middle English, as we can easily read from snapshots of our young language in Chaucer’s or Shakespeare’s deftly bawdy sections. (See Iago’s malicious spreading of the gossip in Act IV that Othello and Desdemona are “making the beast with two backs.”) During the Hundred Years’ War, the French dubbed their fourteenth- and fifteenth-century English enemies les goddamns, which sprang from the English troops’ robust custom of taking the Lord’s name in vain. The British etymologist Geoffrey Hughes notes that the French continue to vamp on that six-hundred-year-old bit of cussing today, calling the British by the phrase they hear them screaming at one another on long, drunken weekends in France, les f**koffs.

The durable Anglo-Saxon verb at the root of that term, which inspires so much off-color creativity, seems to have come to us from the Norse and Swedish verbs fukka and focka, respectively, presumably describing some of what took place during Viking incursions into what later became Scotland and England. As refracted through a few hundred years of English satire and derogation since then, the word is a staple of the Southerner’s linguistic patrimony in crafting profanity, arguably because there is so much blunt poetry that is right with it. Although the old words themselves may be thought of as “careless” language, they have very much been cared for. Accordingly, Southerners treat the act of cursing as eminently social, and thus worth attending with an old, mannerly code.

No rules can be followed to the letter in heated moments, but boiled down, the cursing code follows that for every other Southern circumstance, from stirrup cups on a fox-hunt morning to barbecues and garden parties: when cursing, mind your manners. This seeming oxymoron is not just about the use of coarse language in mixed company, although it does apply to that. Rather, it’s about heeding the fact that, much as we love their many rainbows of connotation, the old four-letter Anglo-Saxon words have stopping power. They strongly punctuate whatever sentence they live in. Like our better chefs, the speaker wants to use the peppers sparingly, lest they overpower the gumbo.

A second important aspect to the code is that a curse should not be an invitation to a pig wallow so much as an invitation to elevate the discourse. You’re not in it to invite your listeners to “go low.” Not so long ago, the curse was actually a curse—a sentence to doom, as with Macbeth’s three witches. One should strive to use metaphor, rhythm, and simile to lend context and drive to any bit of coarse speech. It’s a Southerner’s social duty to curse with whatever fleeting literary beauty can be mustered—welcoming and entertaining folks, not putting them off. This is an ur-Southern contradiction, something to be embraced, not solved. My formidable mother parses the distinction well: “Curse all you want; just don’t be vulgar about it, goddammit.”