I REMEMBER WEEKEND MORNINGS ASLEEP IN my attic bedroom in Birmingham, Alabama, not exactly waking to the smell of bacon, but being awakened by it. Similar to that of freshly cut wet grass, the smell of bacon can travel for miles and never lose its potency. It was just like the cartoons I watched at the time—Pepé Le Pew I remember most vividly—in which you could see the smells; they wafted through the air like spirits. They could corral you like a lariat; they could capture you. That’s what bacon did to me. Half-asleep, I would follow it downstairs and into the kitchen, and still half-asleep eat it until my mother slapped my hand. Save some for the rest of us. Only then would I open my eyes completely, a boy trapped in an unfeeling world where he had to share.

Bacon is a time machine for me to this day. I smell it and it’s Saturday morning. My parents, dead now for many years, are seated around the morning room table. My beautiful sisters—one of whom is also gone—crowd around me, lunging for what is rightly mine, for what I very clearly had dibs on, being the first down. But they strike as fast as copperheads. Our dog Rudy, that little brown mixed breed, as long as a dachshund with the face of a beagle (we called him a dog, though no one was really sure), hid himself beneath the table, as still as a jungle animal, hoping for crumbs. Everyone is happy, everyone is young. Life is something that is just about to happen, and it’s all good.

This is what bacon does to me.

Eating bacon is like dating Taylor Swift: it may not be good for you, but people just keep coming back for more, understanding that a life with a little bacon in it beats a life with no bacon at all. Bacon is full of saturated fat and salt, and yet unlike other foods makes no secret of it. Bacon is honest. Maybe this is one reason we’ve seen an increase in the popularity of bacon and recipes that call for it, such that we can now be said to be experiencing a “bacon mania.” Those of us who were raised on a farm might count a piglet as a dear first pet and eat him later. That’s because bacon is stronger than love itself. I wasn’t raised on a farm but, rather, in front of a television, and yet I too counted a pig as my first virtual pet: Arnold Ziffel, on Green Acres. But that changes nothing. I would eat him if he were bacon. Bacon is not just bacon. It’s bacon ice cream, bacon-infused vodka, chocolate-dipped bacon, and more. It’s the meaty embodiment of Southern culture.

THE ORIGIN STORY OF BANANAS FOSTER couldn’t be easier to document, as it’s one of those foundational recipes on which restaurant empires are built. This tale begins with three New Orleans siblings in the early 1950s. John Brennan, a produce supplier facing down a surfeit of bananas in his warehouse, gave the bananas to his brother, Owen, who was making the family name synonymous with fine Creole cuisine at Brennan’s Vieux Carré Restaurant. Owen passed the bananas along to their sister, Ella, with instructions to create a dessert to honor a New Orleans civic grandee named Richard Foster. Working with the restaurant’s chef, Ella devised the classic tableside preparation, which involves brown sugar, butter, a good splash of rum, a flick of the wrist, a tip of the pan, and a gleeful whoosh of fire. But the brilliance of bananas Foster is how it recasts cherries jubilee—a recipe invented fifty years prior by Auguste Escoffier in honor of Queen Victoria—with New World ingredients. And it left its imprint on a generation of American dinner-party hosts looking to dress up overripe bananas and a tub of vanilla ice cream.

SOUTHERNERS LOVE TO ARGUE ABOUT BARBECUE. Take Eastern North Carolina whole hog, found at such shrines as Skylight Inn BBQ in Ayden and Jack Cobb and Son Barbecue Place in Farmville, versus Piedmont North Carolina shoulders, served in a ketchup-tinged sauce at joints like Red Bridges Barbecue Lodge in Shelby and Lexington Barbecue in Lexington. “People who would put ketchup in the sauce they feed to innocent children are capable of most anything,” columnist Dennis Rogers once wrote in the Raleigh News & Observer. Or Southeastern pork versus Texas beef—smoked masterfully at Franklin Barbecue in Austin and Snow’s BBQ in Lexington (the Texas Lexington). “I mean, pig and burned wood charcoal, and that, to me, is it,” chef John Currence of City Grocery in Oxford, Mississippi, once opined to Eater. “If you don’t have both of those things, to my mind, you don’t have what constitutes barbecue.” Then there’s Alabama’s mayonnaise-rich white barbecue sauce and South Carolina’s mustard sauce, both of which give purists fits. It’s all in good fun, though. At its base, barbecue is a concept we can all get behind: big pieces of meat cooked low and slow in woodsmoke or over smoldering coals. Cheap, tough cuts, caressed by gentle heat and infused with sweet-tart sauces, improve like white lightning in an oak barrel. Nobody can argue with that.

THESE NARROW RIBBONS OF SAND THAT PARALLEL the mainland hold back hurricanes, spring tides, and nor’easters. The South boasts one of the longest single chains of barrier islands in the world, stretching from Cape Hatteras of North Carolina to Florida’s Cape Canaveral, but they can be as different, one from the other, as a weeklong spring-break bender is from a quiet kayak paddle along an uninhabited shore. And barrier islands are alive; formed of sands and sediments moved by rivers and waves and currents and winds, they are in constant flux. They might be clad in dune and marsh and maritime forest, or be so overbuilt with condos and hotels that there’s barely enough room for an oystercatcher to walk on two feet. Barrier islands host some of the South’s wildest beaches and best-known coastal communities, and enclaves where the descendants of slaves still speak in the dialects of their forebears. They are where you find sea grass and sea-grass basket makers, nesting ibis, roosting pelicans, a Scotch bonnet, an empty beach. They’re where you find some of our most garish human footprints and some of our wisest attempts to marry the built environment with the natural one.

THE WORD IS LOUISIANA CAJUN, BORROWED from the Choctaw bajuk for “small river,” and refers to a body of water that flows slowly through low, swampy ground. But a bayou can be a substantial river, such as Buffalo Bayou, which flows from Houston to Galveston Bay; a braided channel to a larger stream; even a long skinny stretch of water that goes nowhere. A bayou can slowly flow in one direction, or carry currents that shift with the tides. Found most notably along the Gulf coast of Texas, Louisiana, and Alabama, and often linked to Cajun and Creole regions, bayous are as much a cultural feature as a physical one. They typically flow in places where a fisherman’s lunch is likely to include boudin and cracklings, and where jokes about Boudreaux and Thibodeaux can send howls of laughter through shores armored with cypress trees and draped with Spanish moss.

THE TRICK TO MAKING BEER CHEESE ISN’T Worcestershire sauce, Dijon mustard, or kosher salt, although every conceivable flavor enhancer has at least one ardent acolyte. To make true beer cheese, in the way the dip has been made along the banks of the Kentucky River since the 1940s, it’s essential to mix together sharp cheddar, flat cheap beer, garlic, and hot sauce—and then not tell a soul exactly how you did it. Secret recipes have been part of beer cheese’s allure ever since the snack was devised by the Kentucky restaurateur Johnnie Allman and his cousin, a head chef at an Arizona racetrack who had some bold ideas about spice. Originally known as Snappy Cheese, it’s traditionally served cold with raw vegetables and crackers, but there’s no shame in warming up a portion for a pretzel or stirring it into mac and cheese. High-end chefs who work in the Southeast (or admire its cuisine from afar) have lately taken notice of the simple dip, serving it with fancy sausages and tweaking its component ingredients. Or so we think; like all good beer cheese makers, they’re not saying.

A BENNE SEED IS TO A RUN-OF-THE-MILL SESAME seed as a juicy heirloom tomato is to the anemic supermarket variety. They may look the same, but there’s a world of difference in taste. Benne came to the South from West Africa by way of the slave trade, the plant often grown in secret by the enslaved, who used the leaves, stems, and seeds as both a nutritional supplement and a flavor enhancer. Over the years, as benne became commoditized and was grown mostly for oil, those flavorful seeds became the more muted sesame seeds we know today. With a renewed interest among history-minded chefs and farmers, heirloom varieties of the seed have made something of a comeback in the South, though short of a trip to a Charleston-area farmers’ market, your best bet is ordering a bag from culinary revivalist extraordinaire Anson Mills. So, no, the benne seed is not the sesame seed, exactly; the benne seed is living history.

(1947–)

ONE OF THE GREAT TORTOISE-AND-HARE STORIES of the modern South began in Madisonville, Tennessee, in 1973, when a high-school guidance counselor with a master’s degree in psychology named Allan Benton bought a ham house from a local farmer. He never pursued his dream of eventually going to law school, instead running his roadside operation, Benton’s Smoky Mountain Country Hams, through an era when most people took about as much interest in an aged haunch of hog as they did in possum potpie. Those were lean times for a self-described hillbilly selling old-timey cured hams and thick-cut smoked bacon. And he did consider caving to the pink, flabby standard that was then earning millions for the competition. As Benton tells the story, though, his dad offered one piece of advice that convinced him to keep the hickory fire stoked: “Son, if you play the other guy’s game, you always lose.” Benton stuck to what he knew, and when the fast-food fog cleared decades later, he was one of the few wood-burning cure masters left. The chefs found him: first, John Fleer of Blackberry Farm in nearby Walland, Tennessee, and then everyone from David Chang of Momofuku in New York City to Paul Kahan of the Publican in Chicago. By 2006, Benton was a national celebrity who could hardly keep up with his mail-order business. And it only took thirty-three years. See Country ham; Cure masters.

(1934–)

I FIRST MET THE KENTUCKY WRITER AND farmer Wendell Berry in 2006, at a memorial service for another great Southern author, the reclusive polymath (and my mentor) Guy Davenport. I had just written a piece for Harper’s magazine about mountaintop removal strip mining in central Appalachia. While about fifty of us gathered at the local arboretum to dedicate a sweet gum tree to Guy’s memory, Wendell told me he approved of my reporting and would like to talk to me about moving forward on the problem—as writers. I felt on that day I had lost one mentor and gained another.

To oversimplify just a bit, I learned style and craft from Guy; from Wendell I learned responsibility. That is, I learned what it means to be a writer with an activist’s commitment to one’s home, one’s native landscape. I could have written “native environment” there, but Wendell is deeply suspicious of that word—of its abstract nature and its inability to inspire dedication to a particular place, a dedication that might lead to an impulse to protect that place. Wendell has been writing in defense of Kentucky landscapes, and in support of their responsible use, since he returned from a teaching job at NYU in 1964. In New York, colleagues had tried to talk Wendell out of leaving. One even dug out the old you-can’t-go-home-again saw, but Wendell knew better. Kentucky was “my fate,” he wrote later in the essay “A Native Hill”—a difficult fate, but one that would not turn him loose. And far from meeting an intellectual wasteland upon his return, Wendell found living in Kentucky the Trappist monk Thomas Merton, the brilliant photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard, the painter and printer Victor Hammer, the painter and shanty boat captain Harlan Hubbard, and the writers Guy Davenport, Ed McClanahan, and Gurney Norman. There is nothing, Wendell soon realized, quite so provincial as the New York literary world.

Wendell and his wife, Tanya, bought a marginal farm overlooking the Kentucky River, and they live there still. He reclaimed an old camp house on the banks of the river and converted it into his writing studio. There he has spent at least four hours a day, almost every day, composing what amounts to around fifty books of essays, poems, short stories, and novels. “I would not have been a poet,” Wendell wrote in one of his many “Sabbath Poems,”

Except that I have been in love

Alive in this mortal world,

Or an essayist except that I

Have been bewildered and afraid,

Or a storyteller had I not heard

Stories passing to me through the air . . .

“In love” and “afraid”—that is the unfortunate dual nature of a man writing to preserve the land he was born to, the land he fears will be lost.

If Wendell Berry had spent the last fifty-some years writing in Vermont, his portrait would be on the state’s money by now. Here in Kentucky, lawmakers hightail it for their offices and lock the doors whenever they see him coming. What it all means is that Wendell’s work as a writer, a public intellectual, and a Kentuckian has been anything but easy. His early essay “The Landscaping of Hell: Strip-Mine Morality in East Kentucky” was written in 1966, but he could have written it yesterday, so stubbornly and ruthlessly has the coal industry held sway over our state. I have watched some environmental activists become eaten up with bitterness and frustration over such inertia. But Wendell has always balanced his righteous anger with affection for his fields, family, and friends. It has, I think, kept him sane.

Here’s one more thing you need to know, and might not suspect, about Wendell Berry: he loves to laugh. It’s a booming, shoulder-rolling laugh that escapes from his long, lanky frame like one of life’s purest affirmations. His friend the late poet Jane Kenyon called it the greatest sound in the world.

THE HEART OF THE HEART OF DIXIE. Other Southern cities may claim other organs—Atlanta, for instance, used to be known as the Kidney of the Confederacy—but Birmingham has always been at the center of everything good and everything bad that has happened in the South, ever since 1540, when Hernando de Soto made his way through these parts, just for a bit, but long enough to have a cavern and a state park named after him. I’m not sure what all happened over the course of the next three hundred years or so, but I do know this: Birmingham didn’t officially come into existence until 1871, six years after the Civil War ended, meaning it didn’t really have anything at all to do with the Great Terribleness so stop looking at us like that.

Until the late 1960s, Birmingham was the industrial South. There were more steel mills and furnaces than barbecue joints and churches, so much so that for quite some time Birmingham was known as the “Pittsburgh of the South.” I don’t know who came up with this nickname and why they thought it was a good thing to want to be the diminutive Pittsburgh, when I have it on good authority that even Pittsburgh didn’t want to be Pittsburgh at the time (they wanted to be called “Motown on the Monongahela”).

At any rate, the steel that built the railroads that brought the South into the twentieth century was made in Birmingham. Kudos. And then . . .

Then, of course, came decades of segregation and racism and hate. I was born beneath that dark cloud. Many of the iconic images of that shameless era happened in Birmingham. Think of Bull Connor—the commissioner of public safety, of all things—who ordered the hoses and the dogs be used against black protesters, and who closed the city parks to prevent desegregation. That was Birmingham. Or “Bombingham,” yet another nickname earned by my hometown, due to its habitual dynamiting of anyone working toward racial harmony, even children at the 16th Street Baptist Church.

Moral: When you’re the heart of anything, you have to expect heartbreak. Birmingham has had its share, and caused its share, too.

But so much is different now. It’s among the most beautiful cities in America. See for yourself. Many who go for a visit stay for a lifetime. The gentle slope of the Appalachian Mountains unrolls like a carpet to create green swelling hills. The steel mills are gone, the air and the water are clean, and it’s where you’ll find some of the best restaurants anywhere—Frank Stitt’s Highlands Bar and Grill, Chris Hastings’s Hot and Hot Fish Club, and more.

As if that weren’t enough, rising above it all is Vulcan, at fifty-six feet tall the largest iron statue in the world. A refugee from the 1904 World’s Fair, otherwise known as the Roman god of fire and metalworking, Vulcan is to Birmingham what the Empire State Building is to New York City, what the Eiffel Tower is to Paris—or, as the French call it, le Birmingham de la France.

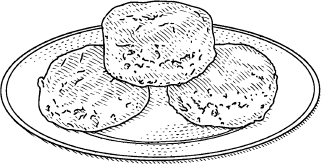

LIKE A STAR WHO GETS REDUCED TO PLAYING the loyal sister as she ages, the biscuit lost its place for a while in the Southern food firmament. Biscuits became something we grabbed at fast-food windows or released from spiral tubes, while cornbread got the raves and appreciation. But there was a time when those roles were reversed.

Before the late nineteenth century, cornbread was everyday food, whipped together from ubiquitous cornmeal that anyone could buy or have ground from their own corn at the gristmills that were an essential part of any settlement. Corn-based breads and pones were easy to make and fast to cook early in the morning before a day of labor. Biscuits were special, the food of the owner’s table. If you had biscuits at breakfast, it usually meant you had—or more likely, owned—a cook who rose early to make them. If you had biscuits, you had flour, ground from soft red winter wheat, less common and more costly than cornmeal. Parties featured beaten biscuits; making them was a truly sweat-inducing chore that involved repeatedly whacking the dough to break down gluten and create the right crisp texture.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, once railroads made it easier to get things like flour and when commercial baking powders became readily available, biscuits became food for everyone. Self-rising flour, with the baking powder already mixed in, made biscuits fast enough that anyone could whip up a batch for breakfast and tuck the leftovers in their pail for lunch.

The recent attention to the roots of Southern cooking, though, has restored biscuits to their starring role. Today, serious cooks are serious about biscuits. We pay attention to the flour, keeping low-protein winter-wheat flours on hand. We search out high-quality lard rendered from old-breed pigs. We look for good buttermilk, to give them tenderness and tang. And we take the handling seriously. Biscuits are less about recipe and more about touch, a deftness that comes only from repeated practice. There’s a reason the finest biscuits were made by cooks and farm wives: the best way to learn to make good biscuits is to make biscuits. Over and over, every chance we get, until they come from muscle memory, not recipe.

Welcome back, biscuits. We missed you.

EVEN IN THE WORLD OF FAST FOOD, THERE are fancier joints. You’ll often find Biscuitvilles situated in the same vicinity as junkyards and payday loan outlets. But the allure of all-day down-home Southern breakfast fare has helped the regional chain grow to fifty-four locations in North Carolina and Virginia. At any one of them you’re likely to encounter a mix of hungover frat boys, thrifty grandmas, and hungry construction workers waiting their turn to order. And at all of them you’ll find an employee, in full view, hand making batch after batch of biscuits from just flour, buttermilk, and shortening—the way God intended. To dress those hot biscuits with country ham, a fried pork chop, or sawmill gravy is to visit the crossroads of comfort food and convenience. Recently, hard-core fans have noticed some new locations pop up with expanded lunch menus and suburb-ready stacked-stone exteriors. That’s dandy, as long as none of this inevitable upscaling interrupts the never-ending flow of biscuits.

(c. 1680–1718)

EDWARD TEACH HAD A BEARD. IT WAS BLACK. When he was in battle, he wove wicks laced with gunpowder into it and lit them on fire, surrounding his head with sparks and billowing smoke. It was part and parcel of what was perhaps the finest bit of pirate marketing ever, as Teach (or Blackbeard, as he became known) preferred fear and intimidation to outright violence, aiming to compel surrender before a fight even broke out. An Englishman by birth, Blackbeard began his career as a privateer during the War of the Spanish Succession and, after it ended in 1714, turned to piracy along the Carolinas and in the Caribbean. When he captured a twenty-six-gun French boat named La Concorde in 1717, he refused an offer of amnesty from England and instead upped the ship’s guns to forty, renamed her Queen Anne’s Revenge, and carried on. Queen Anne’s Revenge was sunk off Beaufort, North Carolina, seven months later, and within the year, in 1718, Blackbeard was killed in Ocracoke Inlet by forces sent by the lieutenant governor of Virginia. But only after he had taken five musket balls, endured twenty sword wounds, and fixed himself in the world’s consciousness as the most famous pirate who ever lived.

IT MAY BE TRUE THAT “BLACK BELT” ORIGINALLY referred to the dark, rich topsoil blanketing nineteen counties that stretch across Alabama’s lower half. But when tens of thousands of African slaves were forced to grow and harvest the cotton sprung from that fertile soil on plantations in the 1800s, the meaning inevitably shifted. After the Civil War, enough free blacks remained to work the land as sharecroppers that they still outnumbered the local population of white aristocracy. The harsh inequities of Jim Crow undoubtedly also helped make the region fertile ground for the civil rights movement in the 1960s, from the Montgomery bus boycott to the televised “Bloody Sunday” attack on peaceful marchers in Selma. Today, the Black Belt designation lives on, now used to define a “heritage area” that acknowledges its painful past while promoting its cultural and natural resources.

THE IDIOMS OF THE SOUTH VARY WIDELY based on location: phrases uttered in isolated mountain hollers differ from what’s said in urban centers, farmlands, mill towns, water-locked bayous, and remote barrier islands. But there is one phrase that comes closer to being a universally recognized Southernism than most any other save “y’all”: “Bless your heart.” A colorful and handy parcel of verbiage, it can be a genuine expression of gratitude, but more often than not it’s wielded to convey a veiled air of disdain with a tinge of pity. Still not getting it? Bless your heart.

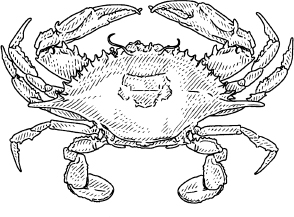

THE ATLANTIC BLUE CRAB, CALLINECTES sapidus, Latin for “savory beautiful swimmer.” Mature, legal-size males and females are known as jimmies and sookies (respectively), and they’re common in coastal waters from Maine to Mexico. They’re hard to clean but easy to catch—chicken-wire box traps baited with bycatch: porgies, spots, yellowtail, grunts, and croakers, fish you wouldn’t eat anyway. Deer liver works best when you have it, or trotlines baited with salt-cured bull nose—crabs love the stuff. Better yet, send the kids down to the dock with net twine, a bushel basket, a fistful of rusty bolts, a half pound of chicken necks, and a dip net. You stay home and boil the water, dusting a little Old Bay on top. (Unless you’re anywhere near Chesapeake Bay, where about half of the country’s commercial catch comes from and where crabs get steamed—never boiled.)

When it’s time to eat the crabs, the claws are easy: pop them with pliers or a pecan cracker, slide the meat out, and dip it in butter—dark meat, the best. Bust off the legs, then peel the shell for white meat on either side. Little fingernails of shell there, but keep at it and suck the meat up if the picking gets too tedious.

Buying crabs? Make sure they’re still alive. Ice on top will keep them stupefied till the water boils. You do not want a crab rodeo on the kitchen floor.

THINK OF BLUEGRASS AS THE COUNTRY cousin of jazz: a brother from another mother, so to speak. The name does not refer only to a particular sort of grass that grows in Kentucky, though one imagines that had to be involved at some point. The operative syllable here is blue, referring to the blue notes you find when you go looking in between the twelve main ones. In its origins, bluegrass is as messy and polyglot as jazz: some old-time music, some Irish fiddle tunes, a bit of gospel, a big injection of blues, some improvisation, and basically whatever else has caught the musician’s fancy at that moment. You know it when you hear it—it’s that mandolin, guitar, fiddle, and banjo, that twang, that whine, that drive. In 1946, Bill Monroe (a Kentucky native) recruited the banjo prodigy Earl Scruggs and the flat-picking guitarist Lester Flatt to form the Blue Grass Boys, and most point to this as the real moment when it all came together as a musical style. See Monroe, Bill.

AN HERBACEOUS PERENNIAL THAT COVERS at least half the lawns in America, Kentucky bluegrass forms lush, soft fields of dark green turf. The common moniker (scientific name Poa pratensis, for the record) comes from the unmistakably blue seed heads that blossom atop the stems, appearing only on two- to three-foot unsheared grasses during spring and summer—so blame our obsession with painstakingly manicured lawns if you’ve never seen the tiny blue clusters. But the pioneers saw it all. European settlers named the Bluegrass region of northern Kentucky for its rolling meadows of this native grass. Although there are more than a hundred varieties of bluegrass nowadays, there’s still a good chance the grass in your own front yard has roots in old Kentucky.

KNOWN AS “AMERICA’S FAVORITE DRIVE,” this 469-mile back road ribbons through Virginia and North Carolina, high atop the spine of the Appalachian Mountains. But it’s far more than a means from point A to point B. A jewel in the National Park Service’s crown, the Blue Ridge Parkway is a finely planned unfurling of mountain meadows, scenic overlooks, old farmsteads, and split-rail fences designed by a landscape architect named Stanley W. Abbott. “The idea,” Abbott explained, “is to fit the Parkway into the mountains as if nature has put it there.”

The idea emerged during a Depression-era visit by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to Virginia’s newly built Skyline Drive, in Shenandoah National Park. Virginia senator Harry Byrd recommended extending the scenic road to Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina. Roosevelt’s Interior secretary, Harold Ickes, approved the park-to-park roadway as a public works project on November 24, 1933.

Abbott, a twenty-five-year-old Cornell University graduate, started by making a long, rugged solo expedition to familiarize himself with the largely unmapped territory. As Civilian Conservation Corps crews surveyed deeper into the mountains, the challenges posed by steep terrain, rock outcroppings, winter snow and ice, and opposed landowners came into sharper focus. Undaunted, Abbott and his engineers made slow but steady progress. By the onset of World War II, 170 miles were drivable; a decade later, half the Parkway was done. By 1968, only seven miles of road remained unbuilt—a tricky stretch along the steep, ecologically fragile flanks of Grandfather Mountain, in North Carolina. The solution, a swooping 1,243-foot concrete segmental bridge known as the Linn Cove Viaduct, enabled crews to finish the Parkway in 1987. On September 11 of that year, fifty-two years after its groundbreaking, the Blue Ridge Parkway was officially dedicated.

The Parkway includes twenty-six tunnels, dozens of bridges, and more than two hundred parking areas, overlooks, and other areas of interest to passing motorists. The road reaches its lowest elevation, six hundred feet, at the James River in Virginia. At North Carolina’s Richland Balsam overlook, the Parkway tops six thousand feet, its highest point.

In addition to providing a brilliant design, the tireless Abbott spent countless hours convincing skeptics “what a little ribbon of land a thousand feet wide and five hundred miles long could contribute to our major objective of conserving the fine landscape of America,” he later recalled. One Michigan congressman called the Parkway “the most ridiculous undertaking that has ever been presented to the Congress of the United States.” Time proved him wrong, of course. Today, the Parkway is one of the most beloved and widely visited destinations in the U.S. national park system. Drive it, and you’ll witness the majesty of the world’s oldest mountain range and better comprehend mountain life in the South.

BLUES MUSIC IS BROADLY MARKED BY A SPECIFIC chord progression over twelve bars, lyrical meter, a call-and-response vocal structure, and an individual series of flattened “blue notes,” played at a slightly modified pitch. It’s more viscerally marked by chilling loneliness, bad liquor, bad women, worse men, dirt-road vocals, and endless reserves of regret. The true origins of the blues are evocatively dusty. W. C. Handy is said to have discovered it in a Mississippi train station in the early 1900s via a traveler pressing his knife into guitar strings, and Handy later became one of the first to publish sheet music for it. But its roots extend deeper, to nineteenth-century Southern plantations, where slaves fought their days by creating a powerful new mixture of African spirituals, folk songs, field hollers, work songs, and hymns, something that could conjure both deep pain and inextinguishable hope. However it happened, the blues came of age in the tents and juke joints of the Mississippi Delta before making its way up- and downriver and into cities that put their own stamp on the music: Kansas City blues is steeped in jazz, Louisiana blues is shot through with bayou feeling and harmonies, and Chicago blues became electric, both figuratively and literally, at the hands of John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters. The true creators of the mid to late 1800s have largely been lost to history, but early recorded pioneers include Son House, Lead Belly, Mamie Smith, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Ma Rainey, and Bessie Smith, artists without whom there would be no R&B and no rock and roll.

BOILED PEANUTS SEEM TO OCCUPY A SPACE between a snack food and a habit, like chewing tobacco. As any fan can attest, the act of loosening the salty, wet little legumes from their shells inspires one’s mind to take a leisurely walk. People eating boiled peanuts are usually engaged in other tasks—driving, chatting, fishing, watching a ball game. (Peanuts are most often boiled at home or purchased at roadside, and are almost never served in a restaurant.) The elusive, liminal nature of the boiled peanut—a strong touchstone of identity in parts of the South yet virtually unheard-of in others; a flavor worthy of highest exaltation in a package that’s wet and messy; that anticommercial streak—is its only certain character trait.

There’s an existential crisis, too. Peanuts (Arachis hypogaea) are not really nuts. They’re legumes, from the family Leguminosae, which includes limas, favas, soybeans, and most any bean you’ve ever eaten. A peanut newly dug from the ground is as damp as a potato and has both the fresh aroma of mown hay and the pleasantly funky one of a dried leaf pile. Shell it and chew the medium-firm seed kernels and you’ll discover a starchy, gently sweet flavor like that of a raw lima bean or sweet pea. It’s a taste of high harvest, the end of August to mid-fall (in our native South Carolina; earlier to the south, later to the north). To us it seems logical—and not unusual—that you might want to boil them or steam them, the way most beans are boiled or steamed before they’re eaten. (If instead you dry the peanuts and roast them in an oven, you will change their flavor, bringing out a nutty, buttery character that the legume doesn’t possess in its raw state, and you’ll have what most Americans recognize as peanuts—roasted peanuts.)

Peanuts came to North America from Africa and the Caribbean with the slave trade, sometime before the American Revolution. African Americans grew and popularized the peanut—both boiled and roasted/baked/parched—throughout the South. Eventually, by the early twentieth century, all Southerners took a widespread interest.

Boiled peanuts catch neophytes off guard, challenging them to think about a familiar food in a new way. And this miraculous transformation is accomplished not by adding any ingredient, but by simply taking the peanut back a step, toward its natural state. Not everyone falls for their distinctive bean-like flavor, but boiled peanuts are undeniably full of personality.

They couldn’t be easier to prepare—if you can boil water, you can boil peanuts. It’s a great activity for a Saturday or Sunday morning; all that’s required is for you to get up from your primary occupation occasionally to maintain the water in the pot. The peanuts are incredibly tolerant, in the sense that they’re difficult to overcook, which allows plenty of leeway for forgetfulness, distraction, and inebriation.

Eating the fragrant peanuts hot out of the pot is a wonderful way to approach them, but gobbling them at room temperature seems the quintessential experience, since they’re most often purchased by the side of the road or in a gas station, in soggy brown kraft-paper bags. The briny peanuts seem to gain something from sitting in the fridge for a few days, too, so feel free to eat them cold, as we often do. Truly, boiled peanuts defy any attempt at gussying up, professionalization, or expertise, and that just might be their ultimate gift to those who love them.

ALBULA VULPES, OR “WHITE FOX,” THE BONEFISH is also known as the phantom, silver ghost, ladyfish, grubber, and, inexplicably, as banane de mer (banana of the sea) by, naturally, the French. It is one of the most coveted of shallow-water sport fish and is usually found in areas with mangroves and sea grasses. For American anglers, that means southern Florida and the Bahamas, where you will be looked upon with a mixture of pity and contempt if you attempt to catch them on anything other than a fly rod. The fish has armor plates rather than scales, a sucker-like mouth, and a snout-like nose. With these it digs about for crabs, shrimp, and other small things, especially on rising tides and often in small groups. Bonefish startle like overcaffeinated guinea pigs at the slightest disturbance, so the angler must place his offering in the direction they’re heading with precision. Too close, and they’ll vanish. Too far, and they’ll fail to register it. If you do get a strike, the fish typically bolts for up to a hundred yards. Then it may rest and bolt back, heading for the mangroves. Since motors frighten bonefish, the guide usually stands on an elevated platform and poles the skiff. When he spots one, he’ll tell you where to cast, as in “Twenty-five yards at eleven o’clock,” expecting you to instantly cast to that spot. When you fail to do this, he will often curse in the local dialect. You will not understand the literal meaning, but the message is unmistakable: the fellow you pay four hundred dollars a day has just called you one sorry-ass fisherman.

THE WOODEN SIGNS AND VINYL TARPS ALONG the back highways of South Louisiana that advertise the availability of hot boudin are typically worded so ecstatically (HOT BOUDIN + COLD BEER = GOOD COMPANY) that travelers might imagine they’ve stumbled across the only source of sausage in a pork-and-rice-deprived county. That’s never the case, of course. Acadians are crazy about the delicacy, which is often the first thing they eat after arising: get yourself a cold Coke and a boudin link, and you’ve got yourself a Cajun breakfast, obligatory if you plan to spend the day fishing. Sold in butcher shops, grocery stores, and gas stations, boudin shares a name with French boudin blanc and not much more. Influenced by German immigrants’ sausage-making mastery and the region’s nineteenth-century rice economy, boudin is typically stuffed with ground-up pig parts, cooked rice, onions, green peppers, and spices, and then steamed for instant eating. Variations are endless: there’s boudin stuffed with seafood, including alligator; grilled boudin; smoked boudin; and boudin balls. The most endangered of all the types is boudin rouge; health inspectors don’t always take kindly to the amount of pig’s blood required to produce its signature flavor and color.

WHAT IS IT ABOUT THE SOUTH THAT drives us to drink? More specifically, what is it about the South that drives us to make the stuff everyone else wants to drink?

Ciders and fruit brandies were once common farm products, made anywhere peaches, apples, and grapes were grown. Rums and Madeiras were widely available wherever there was a port to bring them from the Caribbean or Portugal. But bourbon is so closely linked with Kentucky that many people still mistakenly believe it’s the only place that creates the stuff. Truth be told, under federal standards set in 1964, bourbon can be produced anywhere in the United States as long as it meets a set of other criteria, including that the majority of the mash is made from corn and that it’s aged in new charred oak barrels.

Still, corn grows well in many parts of the country. So why has bourbon always had such strong ties to the South?

A lot of factors played a part in the origins of Southern whiskeys, from clear corn liquor to barrel-aged bourbon. Early life in the South—when much of the region was far from population centers—required self-reliance, the ability to make whatever you would need. The Scotch-Irish settled much of the region, bringing whiskey-making know-how with them, so some form of high-octane alcohol was inevitable. Surviving here economically also meant the ability to turn anything you could grow into something that would bring the best returns in trade or usefulness. Corn grows well even in slightly rocky soil, making it a reliable crop even in mountainous areas. Those mountains were also generally sources of excellent water, filtered through natural limestone so that it was free of iron and higher in calcium, making it perfect for use in distillation.

A bushel of dried corn is heavy. It’s a lot easier to transport it and sell it for more money if you use that corn to make a mash and then distill that mash into alcohol. Pouring that alcohol into oak barrels that are charred on the inside will, over time, transform that raw, clear corn whiskey into something brown, smooth, and packed with flavor imparted from the wood.

From Kentucky, it could take months to transport those barrels by raft down the Ohio River to the Mississippi and on to New Orleans for sale, but even a few months in a barrel could nudge raw corn whiskey on its way to becoming something much more pleasant to drink—and that merchants were willing to buy and resell for a much higher price.

It is also worth remembering one other thing while contemplating Southern bourbons and whiskeys: the role of Southern isolation. Well into the twentieth century, the South remained rural, heavily wooded, and in many places mountainous. That made it possible to produce alcohol free from regulation and, more important, taxation.

The great irony is that the production of alcohol thrived in a place with such strong religious and social strictures against the consumption of it. Perhaps it’s simply human nature: the more the fruit is forbidden, the more of a thrill it is to consume it.

NO SINGLE FIREARM EXPRESSES THE SOUTH’S hunting heritage and history as completely as T. Nash Buckingham’s monstrous 1926 12-gauge A. H. Fox Burt Becker side-by-side, dubbed “Bo Whoop” for its thunderous report. From the 1930s to the early 1960s, Buckingham published scores of hunting stories for major magazines, mostly tales of waterfowling and quail hunting. The tales filled seven book collections—the most famous was the first, De Shootinest Gent’man & Other Tales—and made Mr. Buck a near-household name across the region. The South’s most famous shotgun won notoriety not only because of its featured role in many of the writer’s famous stories, but because the gun vanished for half a century, fostering more fakes and false sightings than the Virgin Mary.

Buckingham lost Bo Whoop in 1948. As he and a buddy were being checked by a game warden, he leaned the shotgun against the car, then the pair drove off, the shotgun forgotten. The gun stayed lost for more than a half century, until 2005 when a gunsmith in Darlington, South Carolina, recognized the ancient blunderbuss when an anonymous owner brought it in to have the stock replaced. Once word got out that Bo Whoop had resurfaced, it didn’t take long for the shotgun to hit the auction block. Buckingham’s godson, Hal Howard Jr., bought it for $201,250, and loaned it for display at Ducks Unlimited’s national headquarters in Memphis. See Double guns.

THOUGH IT ORIGINATED IN CROATIA, WHERE seventeenth-century mercenaries wore scarves around their necks to hold their shirt collars together (the French word cravat literally means “Croat”), the bow tie has evolved into one of the South’s ultimate sartorial expressions. The “string tie” first took root in the region—think Colonel Sanders—but Southerners today don’t discriminate: from bolos to batwings to black-tie silks, in designs ranging from seersucker to turkey feathers, the humble bow tie has found a welcome home in the region.

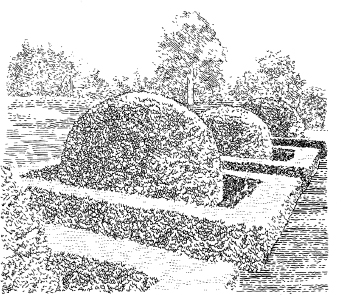

THE BOXWOOD IS A SOUTHERN GARDEN ICON, a small-leaved evergreen that thrives in a variety of soils, with minimal water, and in both sun and shade. While hundreds of box varieties exist, the two commonly associated with the American South are Buxus sempervirens (American boxwood) and a dwarf variety, Buxus sempervirens “Suffruticosa” (English boxwood). Many are surprised to learn that the so-called American box dominated the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century gardens of England. A fungal blight that originated in Europe in the 1990s now threatens both varieties of the historically hardy shrub.

Boxwoods are known for bringing order and symmetry to gardens, whether planted individually or in hedges. In gardens across the South, they form allées, perennial borders, and elaborate parterres. They’re even orderly growers, requiring only one or two trimmings per year. The use of boxwoods reached peak popularity during the Colonial Revival movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, especially in Virginia. Look for classic examples in and around Colonial Williamsburg. The restored box gardens at George Washington’s home, Mount Vernon, are particularly impressive, with French influence plainly visible in the elaborately sculpted parterre fronting the conservatory.

THE TRUE DEFINITION OF A POCKET RETRIEVER, the Boykin spaniel is a gundog that rarely tops forty pounds. It’s also one of just a handful of truly Southern dog breeds. Established in the early 1900s near Camden, South Carolina, by a sportsman named L. Whitaker Boykin, the breed was developed to hunt the local swamps out of small boats. (This characteristic inspired an oft-used phrase describing the Boykin as “the dog that doesn’t rock the boat.”) These days hunters still take “the little brown dogs” into the swamps in pursuit of ducks and woodcocks but also into the field for quail and other upland birds. In 1985, South Carolina made the Boykin its state dog, even designating an official day to celebrate the breed, September 1. No surprise, that’s also the opening day of dove season.

THE ONLY SALMONID NATIVE TO THE SOUTH, found as far south as Georgia, the brook trout, technically, is no trout at all. It’s a char more closely related to Dolly Varden and arctic char than rainbow and brown trout. Its Latin name, Salvelinus fontinalis, means “dweller of springs,” and it is in high, pure, cold waters that it has remained since the last of the glaciers slid northward. It may not leap like the rainbow or run like the brown, but the brook trout gives no ground on beauty. In the hand, a wild brook trout is a riot of color, but in the water it utterly disappears. Blue-haloed red spots become tiny bits of stream-bottom stone. Yellow vermiculations across a moss-green back turn to spots of dappled sun. Every aspect of the fish’s adornments is designed to keep it hidden, out of the clutches of otter, owl—and angler.

(1933–2006)

THINKING ABOUT SCULPTING A MOUNT Rushmore of American music? Start right here (and be sure to reserve enough granite up high for the hair). Born in 1933 in Barnwell, South Carolina, James Brown developed both an inhuman work ethic and the knowledge that in the 1960s you had to rattle stages not just with your music alone—though his would have sufficed—but with sweaty, glittery, flying, sequined, spinning, knee-dropping, screaming, unstoppable, and caped style. Brown’s catalogue is an absurdly stuffed hit list of songs one can’t imagine life without: “I Got You (I Feel Good),” “Cold Sweat,” “Try Me,” “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag,” “Get Up (I Feel Like Being a) Sex Machine,” “Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud.” His self-assigned title, “the hardest-working man in show business,” is an accolade no modern musician dare claim for himself—Brown will possess it eternally, along with “Mr. Dynamite,” “Soul Brother No. 1,” and “the Godfather of Soul.” That said, Brown also had more than his share of demons, which throughout his career led him to jail sentences, seemingly bottomless tax problems, a trail of broken relationships, and at least one mug shot gone viral. Yet through it all, driven less by financial requirements than a fierce need to perform, Brown achieved a standard that will be forever imitated. But never come close to being touched.

(1951–2004)

IN 1980, A TWENTY-NINE-YEAR-OLD OXFORD, Mississippi, firefighter named Larry Brown decided to try writing stories. A father of two with another child soon to come, he’d been working odd jobs to make ends meet—building fences, hauling hay, painting houses—and figured writing might be an easier and more satisfying way to earn an extra buck. It wasn’t. The more stories Brown wrote—more than a hundred, he later estimated—the faster they came boomeranging back into his mailbox affixed with rejection notes. Barry Hannah, then writer in residence at the University of Mississippi, took to hiding when he’d spot Brown coming his way with a manila folder under an arm, lest Hannah be served with yet another unsalvageable story. When Brown finally published a story, it was in Easyriders, a biker magazine known not for its writing but for the tattooed models and chromed-out choppers gracing its covers.

There seemed little to suggest, in this long and tortured start, that Larry Brown would go on to become a titan of Southern literature—a novelist, essayist, and short-story writer whose name is often and rightfully invoked in the same breath as Harry Crews, Cormac McCarthy, and Flannery O’Connor. But Brown was almost manically driven, and year after year of writing and reading and rewriting, along with the mighty artistic awakening it roused, eventually equipped him with the literary equivalent of perfect pitch: an astounding ear for the music of drawling speech, a keenly sensitive eye for the kudzu-riddled landscapes of his native countryside, and a breathtaking ability to render the foibles of human existence with warm but unblinking precision. Brown took a sledgehammer to Samuel Beckett’s notion that the true artist comes from nowhere. Suffusing his work was what winemakers call terroir: the peculiar tang of a specific locale, the distinct and unfakeable flavors imparted by a collusion of factors such as soil (clay), climate (humid), and tradition (Faulkner et al., plus all the stories Brown heard traded at country stores and during quiet nights at the firehouse).

Brown’s books—foremost among them Dirty Work (1989), Big Bad Love (1990), Joe (1991), Father and Son (1996), and Fay (2000)—were set mostly in the outer precincts of Lafayette County, and peopled with hard-living characters with a fondness or weakness (take your pick) for sex, cold beer, cigarettes, bare-knuckled violence, pedal-steel ballads, and riding the gravel back roads in a meditative funk. From the first page Brown liked to load his characters with trouble—“sandbagging,” he once called it—and then chronicle their struggles to cast off this load, like the Old Testament’s God lobbing ordeals at Job. Yet by gauging what they could endure, Brown showed what all of us can endure, calculating the carrying load of existence not unlike the way O’Connor, from another angle, charted the boosting powers of grace. His prose was lean but its effects were lush.

Those effects yielded Brown a devoted cult following—particularly among songwriters, ranging from the Texas legend Robert Earl Keen to the stadium-filling Tim McGraw, who saw reflected in Brown’s work that bedrock definition of a great country song: three chords and the truth. At the time of Brown’s sudden death in 2004—a heart attack claimed him in his sleep, at the age of fifty-three—he had exponentially exceeded those early firehouse ambitions. He had carved his name into the thick trunk of American literature, and had enriched that literature with a shatteringly singular voice that continues to be celebrated and imitated but—like the voice of Hank Williams, which often serenaded Brown as he’d roam the twilit back roads in his dun-colored truck—cannot ever be matched.

IF YOU’VE EVER EATEN A BRUNSWICK STEW made with squirrel, you won’t forget the distinctive winey sweetness of the meat. That Brunswick stew—the one cooked in a cast-iron cauldron over an open fire—figures into many a multigenerational Southern family’s mythology. But let’s face it: people talk squirrel and cook chicken. Today’s stews, unlike yesteryear’s catchall of small furred game, usually combine long-simmered chicken along with its broth, corn, tomato, butter beans, and a few shakes of Worcestershire sauce. The farther south you head from Brunswick County, Virginia, to the coastal town of Brunswick, Georgia, the more likely you are to find threads and chunks of smoked pork in equal measure to chicken. The two Brunswicks, of course, have long fought over naming rights. Perhaps the Virginia stews are thicker and more simply seasoned, a one-dish meal. The more tomatoey Georgia stews tend toward soupiness and have a peppery bite and vinegary zing. Indeed, barbecue vendors throughout Georgia offer Brunswick stew as a thrifty side dish that uses up all the leftovers. Wherever Brunswick stew is claimed, there will be a full calendar of festivals and cook-offs.

(1946–)

NO ONE HAS MONETIZED S UNSETS AND MARGARITAS more than James William Buffett, whose island escapist sounds are played in every beach-bum bar from Hawaii to Aruba, not to mention his own restaurants. Born in Mississippi and reared in Mobile, Buffett began his career playing his folksy music on the streets of Nashville. After little success, he bought a one-way ticket to Miami, eventually ending up in Key West with his good friend Jerry Jeff Walker. There he found his muse. His 1977 breakthrough album, Changes in Latitudes, Changes in Attitudes, contained his now-ubiquitous single “Margaritaville,” and subsequent hits like “Cheeseburger in Paradise” and the 2003 duet with Alan Jackson “It’s Five O’Clock Somewhere” provided a rallying cry for happy hours in the sand. To his credit, Buffett was one of the first artists of the past forty years to recognize that the real money was in touring—he has hit the road every single year since 1976—and his die-hard fans, dubbed Parrot Heads, gather en masse wearing loud floral-pattern shirts and crazy hats, dreaming of ditching their day jobs for island life a few hours each night.

HERE’S WHAT A BUTTER BEAN MOST CERTAINLY is not: a conventional lima bean that Southerners have given a more palatable moniker. Butter beans aren’t green; they’re creamy white. They should never be served from a can; look for them sold straight from a cooler in plastic bags along Southern roads for about a three-week period sometime between June and August. And they don’t have any tartness; they’re sweeter and smoother than their sometimes off-putting mass-market lima cousin. Also known as a Dixie bean or sieva, the butter bean has been a go-to hereabouts for succotash and stews since the 1700s. You can boil them until tender and dress simply with lemon zest, sea salt, and olive oil. Or cook them with a big ol’ ham hock and spoon them over hot crusty cornbread for a classic helping of Southern goodness.

FOR ALL THE CONFUSION AROUND REAL buttermilk, its definition is simple: honest-to-goodness, farm-fresh, can’t-buy-it-at-the-supermarket buttermilk is the sour liquid that runs off freshly churned butter. So why aren’t we swimming in it? Because the way we make butter has changed. On a nineteenth-century farm, you would have made butter by leaving fresh milk out in the springhouse until the cream rose to the top and then churning it. As the milk sat out for twelve or fourteen hours, friendly bacteria would thicken and sour it. Once churned, it would have given you complex cultured butter and buttermilk that would have added zing to biscuits, pies, and fried chicken. Today, of course, most of our butter comes from factories. While cultured butter remains popular in Europe, stateside, we prefer it sweet. And if the cream doesn’t sour, the buttermilk doesn’t either. So modern dairies simulate old-fashioned buttermilk with cultured milk, which is a passable substitute but lacks the acid bite and butter flakes of the real deal. If you want to make biscuits that taste just like your great-great-grandma’s, you’ll need to either find an old-fashioned dairy or do as your ancestors did and churn your own butter.