(1940–)

BILL DANCE IS AMERICA’S FAVORITE FISHIN’ Buddy. His TV fishing show, Bill Dance Outdoors, has been on the air since 1968 and made him a cult figure in the bass-fishing world. From his home in Collierville, Tennessee, Dance oversees a fishing empire that includes not only television but also tackle endorsements, how-to seminars, his own magazine, and a series of popular “blooper” videos, compiling his legendary pratfalls from the show (Fishing Bloopers, Volumes 1, 2, 3, and 4). There’s even a Bill Dance app.

This level of popularity results from a happy convergence of several factors. It doesn’t hurt to be a superb angler. Before retiring from competition in 1980, Dance won twenty-three National Bass Titles, qualified for the Bassmaster Classic (the Olympics of bassdom) eight out of nine years, and was three times named B.A.S.S. Angler of the Year. It’s even better if you’re a down-to-earth guy whom people enjoy having in their living rooms. And if you have a wet sense of humor (there is no dry humor among anglers) in which you are frequently the butt of your own jokes, better still. Dance’s Fishing Bloopers are consistently best sellers—a four-minute clip from Volume 1 on YouTube has exceeded two million views (and counting) over three years. Even all these ingredients, though, can’t fully explain Dance’s enduring appeal. There’s that certain intangible, something you can’t describe but recognize when you see it: authenticity. Whether you see him in person or on-screen, you immediately sense that the unpretentious, outgoing fellow signing autographs or talking to the camera is exactly who he appears to be. He’s Bill Dance.

THE DARK ’N STORMY IS TO THE GIN AND tonic what whole wheat is to white bread: both drinks may be highballs garnished with a lime, but the former is possessed of more grit and gumption than its milquetoast cousin.

The Dark ’n Stormy is often served in bars in coastal areas, likely the effect of sailing culture and the rum’s long ties to the island of Bermuda. It’s made—by law—with Gosling’s Black Seal Rum, a dark, funky liquor made in Guyana and bottled by the Gosling family in Bermuda, as it has been for two centuries. The Dark ’n Stormy cocktail was apparently invented on the island after World War I and is one of the few cocktails that’s trademarked by a distillery.

The construction of a Dark ’n Stormy—er, make that a Dark ’n Stormy®—is simple. Start with a tall glass and mix spicy ginger beer with a jigger of dark rum—use Gosling’s unless you enjoy corresponding with attorneys. Add a few ice cubes and a healthy squeeze from a wedge of lime. Then sip, preferably with a view of sun-dappled water that’s at the very least brackish. Bonus points are awarded if the water is full-on briny and framed by teak planks with brass fittings.

PRIOR TO REFRIGERATION, MEAT DIDN’T LAST too long in the swelter and humidity of New Orleans. So nineteenth-century cooks got creative to keep meat from spoiling: they jellied it. Originally, this meant simmering down the continental beef-and-vegetable stew known as daube to make it last for multiple nights. A chef would reconstitute it before serving. In time, some savvy cook realized that concentrated daube glacé was a worthy dish by itself. Traditionalists still serve slices of the old-school terrine as a holiday hors d’oeuvre, with garlic croutons or crackers.

HERE’S DAUFUSKIE ISLAND BY THE NUMBERS: 32°6'47" N, 80°51'59" W. All of fifteen square miles, it’s the southernmost inhabited spot in South Carolina. Population three hundred, made up of descendants of slaves, sundry Georgians who blew ashore here for reasons about which you do not casually inquire, and shell-shocked Northern transplants who imagined they were moving to the next Martha’s Vineyard. Six thousand acres of high ground—on a raucous holiday weekend, very high ground. (Listen to Jimmy Buffett’s song “Prince of Tides” for reference.)

You could call Daufuskie a world apart: no bridge, no problem. It’s fourteen miles from the nearest traffic light, with yoga infrequent and frozen yogurt nonexistent. The fast food has fur, fins, or feathers. Two beer joints: come July, you can’t see the bars for the bikinis, the gumbo makes you sweat, and they sweep up the eyeballs come closing time. Naked on the beach? No problem with that, either.

A great time warp—instant 1956—Daufuskie boasts America’s largest collection of freedman architecture, the homes, churches, and schools of the first generation up from slavery. The entire island was declared a National Historic Landmark District in 1982; tours daily. Notoriously independent locals call Daufuskie “the right side of the river.” By implication, the entire North American continent is the wrong side.

NEARLY HALF A CENTURY AFTER THE PUBLICATION of James Dickey’s 1970 novel (and the 1972 movie classic whose screenplay he cowrote), banjos, Southern white water, and backwoods savagery remain, in American pop culture, inseparable. “My story is simple,” Dickey once told an interviewer, “there are bad people, there are monsters among us. . . . I wrote Deliverance as a story where under the conditions of extreme violence people find out things about themselves that they would have no other means of knowing.” See Dickey, James.

by Julia Reed

A FEW YEARS AGO, I WAS ON A BOOK TOUR that took me everywhere from Knoxville, Tennessee, to Manchester, Vermont, and I found myself having to explain—a lot—what I meant when I referred to the Mississippi Delta, where I was born and raised. Usually I made like a first-grade teacher and held up my forefingers and thumbs in front of my face in the shape of a diamond. “This is Memphis,” I’d say, tapping my fingers together at the top. “Down here, where my thumbs meet, is Vicksburg, and over here on the right is the Yazoo River. The Mississippi is on the left, to the west.” I repeated what the Greenville-born novelist David Cohn said, about the Delta beginning in the lobby of Memphis’s Peabody hotel, where ducks—descendants of live decoys left there by long-ago Delta hunters—still swim in the marble fountain.

I explained that the Delta is not an actual delta but one of the richest alluvial floodplains in the world—one pretty much uninhabitable until well into the 1820s, when a handful of folks rich enough and crazy enough (Cohn called them “pioneers with means”) turned up to literally hack it out. They’d already built their grand houses in other parts of the South, where the land was beginning to tap out. Now they were willing to risk yellow fever and countless slaves and members of their families to clear the oft-flooded tangle of primeval swamp and hardwood forest that had been all but untouched for thousands of years by anyone except the mound-dwelling “Indians.” Necessarily adventurers and gamblers at heart, they were anxious to get at the sandy loam that became known as Delta Gold.

By that time, my audience was transfixed, so it became more personal. My hometown of Greenville, I said, is the most sophisticated place I’ve ever lived. It’s where I got my first byline, for a review of a book written by my next-door neighbor, the National Geographic contributor Bern Keating, in our newspaper, the Delta Democrat-Times. I told them how Hodding Carter II, the paper’s founding editor, had won a Pulitzer Prize for writing a series of editorials in support of racial and religious tolerance as early as the 1940s. Carter, a crusading young newspaper editor from Louisiana, had been lured to Greenville by William Alexander Percy, the poet and planter whose literary influence on the region is enormous. He inspired countless writers, including Walker Percy, his much younger cousin whom he adopted, and Shelby Foote, Walker Percy’s best friend.

I reminded them that we’d never had much truck with the “moonlight and magnolias” Old South, and repeated what Shelby Foote once told an interviewer: “The Delta is a great melting pot.” Foote’s grandfather was one of a thriving group of prominent Jews who came to the Delta from Austria, Poland, and Russia. When Greenville was incorporated after the Civil War, the first elected mayor was Jewish, as were the first businesses to open. There was also a sizable Syrian population, who, like most of the Jews, had arrived as traveling salesmen, as well as a large influx of Chinese, whose influence, Foote said, was “considerable.” Arriving in the area as itinerant railroad workers, they drew the line at picking cotton and chose instead to open small businesses (primarily grocery stores) catering to the Delta’s majority African American population.

Finally, I told them that we have always, from the get-go and by necessity, been seriously adept at making our own fun. And that everywhere there are reminders of that ancient forest from whence we sprang. Before my parents bought our house, there had been a yellow-fever cemetery just beyond our backyard; even now my mother yells at me to shut the door lest a snake get in. In high water, the odd black bear, the population of which once numbered in the tens of thousands, has been known to wander into civilization.

The latter is the kind of stuff that always left them wide-eyed. But there was lots more that I couldn’t explain, the stuff better written about in songs or fiction. The way my heart skips a beat every time I drive over that last hill outside of Memphis and into what feels like an enormous dome turned on its side. That earthy chemical smell more powerful than any of Proust’s madeleines. The signs naming towns that read like reassuring mantras as I blow by: Rena Lara, Midnight, Nitta Yuma, Louise.

There’s the breathtaking starkness of the landscape in winter, the sunsets that drench the sky, my favorite stretch of blacktop connecting 61 to Old Highway 1 at Duncan, not far from where Robert Johnson is said to have sold his soul. There’s the memory of just-caught brim and crappie frying in a black-iron skillet at the Highland Club on the banks of Lake Washington, one of the many oxbow lakes formed by the Mississippi, or the first time I ate a hot tamale at the legendary Doe’s Eat Place. No matter what, there’s the soundtrack: Johnson, Albert King, B. B. King, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Son House, John Lee Hooker, Charley Patton, Muddy Waters, Son Thomas. The list goes on and on. More recently, there’s been Eden Brent channeling Boogaloo Ames on the piano or Duff Dorrough bringing me to my knees with “Rock My Soul.” I listen to it all and realize that what I should have said to everyone who asked is that the Delta is a great gift, from thousands of years of flooding and all those who carved it out and worked it afterward in conditions so insufferable that it gave us the blues. It’s also inseparable from who I am.

(1928–2016)

THORNTON DIAL HAD ENORMOUS HANDS. For many decades, he put them to singular use, crafting found objects—including doll parts, metal scrap, paint, old shoes, and springs—into works of art now coveted by such institutions as the Metropolitan Museum of Art. For most of Dial’s life, though, such acclaim must have seemed about as likely as aliens touching down in his Alabama front yard. Born to an unwed teenager in Emelle, Alabama, in 1928, Dial dropped out of school in the third grade and never learned to read. He moved to Bessemer, Alabama, in 1941, and after working a variety of odd jobs, Dial found work building boxcars for the Pullman Standard Company, where he remained until retirement. Throughout it all Dial made art but remained in essence unknown until in his fifties, when a collector named William Arnett visited him on a tip. In time Dial became one of the rare African American self-taught (or “outsider”) artists to find success within the traditional spheres of “insider” tastemakers.

(1923–1997)

JAMES DICKEY WOULD HAVE BEEN A LEGEND even if he hadn’t written Deliverance, the 1970 novel and subsequent film for which he is best known. He was a National Book Award winner and a poet laureate of the United States. Yet strike even that from his record and the epic stories of the man would most likely still be floating around simply because of his larger-than-life personality. The author Pat Conroy, a former student of Dickey’s, once said Dickey made Ernest Hemingway look like a florist from the Midwest. Large, loud, and preternaturally talented, Dickey was born in Atlanta, served in the Air Force, and later quit his job as an advertising executive in order to write. His widely celebrated poetry—a high-test vernacular concoction Dickey dubbed “country surrealism”—became even more powerful when read aloud in his booming voice. Yet it was his first novel, Deliverance—a spare, testosterone-driven tale of Atlanta suburbanites caught in a backwoods Appalachian hell—that made the biggest impression. Ironically, the line Dickey is perhaps most identified with—“squeal like a pig”—wasn’t even his. It was an inspired bit of perverse improv delivered on the film set. But that seems fitting too, for in the end, James Dickey was nothing if not an inspiration.

(1928–2008)

BO DIDDLEY PASSED AWAY FROM HEART failure on June 2, 2008, at age seventy-nine, and it’s easy—in the aftermath of his death—to bestow lofty titles on him. But the reality is that Diddley was the originator of rock and roll, the most influential figure in the history of popular music. Muddy Waters and Chuck Berry came from straight-up blues, but Diddley was different: something more primal, evil, and dangerous. The Bo Diddley beat—bonk, ba donk, donk donk donk—is the most frequently borrowed riff of all time, showing up in songs such as Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away” and U2’s “Desire.” Elvis Presley, it has long been supposed, copped his stage moves from Diddley. Sure, Berry was a monumental figure in rock and roll, but his keyboardist Johnnie Johnson cowrote many of his hits. The Stones wouldn’t exist without Bo Diddley, and even John Lennon, when asked what he wanted to do when he arrived in America for the first time, said: “I want to meet Bo Diddley.” The Clash asked him to tour with them. U2 adored him. Only Little Richard comes close to Diddley’s significance, and until the good reverend passes on, let’s just anoint Bo as the king.

But Diddley never reaped the full benefits of his influence. He signed away the publishing rights to his music for a $10,000 down payment on his first house, a bitter pill that he swallowed until his death. He once famously said: “Don’t trust nobody but your mama, and even then, look at her real good.” Until his stroke in 2007 shortly after a show in Council Bluffs, Iowa, Diddley played about a hundred dates a year, each a lesson in the theatrics of rock and roll with its ruckus of high kicks and searing work on his custom-made cigar-box-shaped guitar.

By all accounts, Diddley loved being just an average joe to the residents of Archer, Florida, where he lived on a seventy-six-acre farm. “He always loved doing regular guy stuff,” says his band member Frank Daley. “We were in Santa Barbara and he called me up and said, ‘Let’s go to the hardware store.’ He was looking for a big tarp to cover God-knows-what at his farm. He found this big blue thing, rolled it up, and put it in his suitcase.” Diddley loved to cook chickens and turkeys in a smoking pit on his property, and drive around in his tractor moving earth around.

“I’d do his taxes, and every year there was an expenditure for sand,” says Diddley’s comanager Faith Fusillo. “He would get piles of sand and just move them from spot to spot. I was like, ‘How am I going to write this off?’”

Through his music, Diddley did move heaven and earth, and though his influence as Bo Diddley was never far from the minds of the people attending his funeral, it was the life of Ellas McDaniel—father, grandfather, and great-grandfather—that was celebrated during a four-hour “homegoing ceremony” at the Showers of Blessings Harvest Center in Gainesville. As the choir and band cooked up a chills-inducing spiritual, Diddley’s casket was wheeled in, followed by more than forty family members chanting “Hey, Bo Diddley” and led by his oldest daughter, Evelyn, or “Tan,” who danced maniacally behind the slow-moving casket.

Once most of the overflow crowd was seated, the testifying and singing began. City officials read proclamations from Gainesville and Archer—Gainesville’s mayor announced to raucous applause that the city’s downtown square would soon be renamed Bo Diddley Plaza. Diddley’s grandson Garry Mitchell—wearing Diddley’s black leather cowboy hat with a silver eagle medallion in the front and two small badges on the side—spoke for the family. “Many times Grandpa and I would talk, almost in secret,” Mitchell said. “Our conversations on his life and mine were almost intertwined. I thank God for that cycle, because his legacy shall live on. Grandpa was awesome; he was way before Elvis Presley. He always got up way early, so early that he tapped the roosters on the shoulder and said: ‘You forgot to crow, because I’m already here.’”

Though Diddley didn’t succumb to the pitfalls of rock and roll—he never did drugs, and drank only occasionally—religion was never a huge part of his life until near the end. “The night he died, all of us were gathered around him,” says his comanager Margo Lewis. “He grabbed my hand, told me he loved me. His friend Sam Green began singing the old spiritual ‘Walk Around Heaven.’ He was in and out, but when Sam finished, he sat up, shook Sam’s hand, and said, ‘Whoa.’ He knew he was on his way.”

And Diddley was truly sent out in style. As his longtime backing band—led by Debby Hastings, his bandmate of twenty-five years—softly played his signature song, “Bo Diddley,” his casket was wheeled out into the steamy Florida sun. Brushing past flower arrangements sent by such admirers as Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, George Thorogood, and Jerry Lee Lewis, Diddley’s casket was loaded into the hearse as tears streamed down many faces. He was gone, but the originator of rock and roll was finally going home.

TEN MILES BEYOND THE SIPSEY WILDERNESS and sunk more than a hundred feet from the surrounding forest, Dismals Canyon looks more like something out of Jurassic Park than Northwest Alabama. Dump-truck-sized sandstone boulders furred with moss form dozens of shaded, fern-filled grottoes on the canyon’s eighty-five-acre floor. The gorge is so remote, the notorious traitor (and original Southern separatist) Aaron Burr hid out there while plotting his takeover of Texas before the law caught up with him in 1807. Jesse James reportedly did the same after an 1881 robbery in Muscle Shoals. But all of that pales in comparison to the main event: the show put on by the larval form of Orfelia fultoni, a relative of fungus gnats, known as Dismalites. Just after sunset on spring and summer nights, the tiny bioluminescent creatures begin to glow, covering the canyon’s cliff faces in galaxies of pale blue lights. Outside of New Zealand, Australia, and a few isolated pockets of the Southern Appalachians, Dismals Canyon is one of the only places in the world where the insects are found. Luckily, taking in the Dismalites’ glow is easy: following the installation of a staircase, visitors no longer must squeeze through Fat Man’s Misery—a sixteen-inch-wide crack between two boulders—to take a guided nighttime tour.

THE FIRST MEAL I EVER ATE AT DOE’S EAT Place, the legendary steak and hot tamale restaurant in my hometown of Greenville, Mississippi, was, as it happens, in utero—there’s a photo of my mother sitting on the slightly sagging front steps when she was seven months pregnant with me. My first actual memory dates from at least two years later, when a plate of unshucked “hots” was placed before me, commencing a love affair that continues apace.

The hot tamale is a product of the extraordinary commingling of cultures that has marked the Mississippi Delta from its earliest days and of which Doe’s itself is a prime example. The father of Dominick “Doe” Signa arrived in Greenville in 1903, part of a wave of Southern Italian immigrants to the area, and opened a grocery store in the same building that now houses the restaurant. Located on Nelson Street, the city’s unofficial African American Main Street, it was part of a bustling scene that included late-night barbershops, blues clubs, sidewalk craps games, fish markets, and more than a dozen grocery stores operated by Chinese Americans who arrived around the same time as the Italians.

When the devastating 1927 flood all but shut down the grocery store, the young Doe turned to bootlegging. In 1941, after selling his still for three hundred dollars and a Model-T Ford, he turned the store into a honky-tonk and takeout joint featuring fried buffalo fish, chili, and the now-famous hot tamales (made from a recipe Doe acquired from a friend and that his wife, Mamie, improved). In an arrangement that turned segregation on its head, African American customers came through the front door, while the occasional white customer entered through a side door into a back room, where Doe served steaks grilled on the mammoth broiler up front. Within a few years the back room, or “eat place,” became so popular that Doe shut the tonk and developed a “menu.” While there has never been a paper or even a blackboard version, regulars know that it consists of chili and tamales, spaghetti and meatballs, fried shrimp, hand-cut french-fried potatoes, salad, garlic bread, gargantuan sirloin and porterhouse steaks, and, until the shucker (Doe’s older brother Jughead) died, oysters on the half shell.

Doe’s gained national renown in the 1960s and ’70s, when Greenville became a magnet for national reporters covering the region’s civil rights and political upheavals—in no small part because my father, then the chair of the fledgling Mississippi Republican party, and Hodding Carter III, the editor of our Pulitzer Prize–winning newspaper, the Delta Democrat-Times, invariably took them to Doe’s for dinner. Bowled over by the food and free-flowing whiskey and wine (customers bring their own bottles, a holdover from the fact that until 1966, the whole state was officially, though not remotely in reality, dry), they returned to their various editors with tales of the exotic “eat place.” The Washington Post and New York Times followed up with profiles, and since then, Doe’s has appeared in countless publications.

From the get-go it was a family operation. Doe’s sisters ran the “dining rooms,” while Jughead’s wife, Florence, manned the fry “station” (three heavily encrusted black iron skillets on a four-burner gas stove) until she was put in charge of the iceberg lettuce salad. Such is the magic of its dressing—an ineffable combination of olive oil, garlic, lemon juice, and salt—that customers have been known to drive long distances to leave their own wooden bowls for Florence to “season” over time. When Doe retired in 1974, his two sons, Doe Jr. (“Little Doe”) and Charles, took over. These days the steaks are cooked mostly by their sons, Charles Jr. and Doe III, who stand on the same worn floorboards in front of the same broiler their grandfather did. Florence still turns up a couple of nights a week to make salad. Even the waitresses are part of the dynasty. Judy Saulter, who’s been waiting tables since 1970, recruited her daughter Debra to join her in 1988.

A side room (where the family once slept) was opened up in the 1960s, and another back room around 1980. Otherwise very little has changed, though the broiled shrimp Big Doe once offered to regular customers on Friday nights was formally added to the menu sometime in the 1980s, and the steak selection now includes filets and rib eyes. Though credit cards are now taken, regulars can still simply sign the ticket before they depart; reservations are still taken on the black rotary phone and written down in a spiral notebook. Until the recent addition of Sysco cheesecakes, dessert consisted of the lollipops in a glass jar by the cash register. I’ve celebrated many a birthday with a Doe’s “cake,” a loaf of French bread stuck with lollipops and candles, and I’m relieved to know I can count on many more.

SOME HERALD DOGWOOD TREES AS THE MOST breathtaking plants in the South—they put on a year-round show, with fragrant spring blooms, gorgeous branch sprays in summer, turning leaves and bright berries in fall, and lovely buds come winter. Although today we may regard them mainly as eye candy, to Native Americans they were a whole lot more. When the dogwoods’ lovely white flowers burst into bloom, they knew it was time to plant corn. They also used the hardwood to make daggers and arrows (which is why the English initially called the tree a “dagwood”), toothbrushes, a tobacco mixture for pipes and sacred religious ceremonies, and even poison to use against rival tribes (the sap can be toxic). It wasn’t until the 1600s that the tree became known as the dogwood, most likely because the wood was boiled to create a medicinal wash to treat skin conditions like mange in dogs. (A less likely but more cocktail-party-suitable tale of the name’s origins: on windy days branches knock into each other and sound like barking.) Today the tree—native to the eastern United States, and the state tree of North Carolina—remains a beacon of spring and its bounty. Those first blossoms’ arrival signals to knowing fishermen that the spring bite is on. Tip for a worthwhile detour: in eastern North Carolina’s Sampson County, north of Wilmington, the nation’s largest dogwood—certified by none other than the National Register of Big Trees—boasts a branch spread of forty-eight feet. Pretty as a (panoramic) picture.

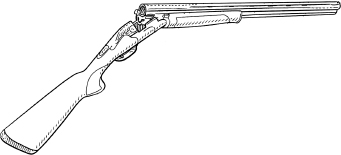

DOUBLE-BARRELED SHOTGUNS, WHETHER SIDE-BY-SIDES or over-unders, are de rigueur in the quail fields of the South. They have long been known as gentlemen’s guns, handmade for dukes and barons who would tolerate only the finest, a tradition continuing in bespoke British Best shotguns today. American doubles experienced a golden age from the early 1900s until World War II, from makers such as L. C. Smith, A. H. Fox, Ithaca Gun Company, and Parker Bros., and have come down through the generations. The most famous double in Southern lore is known as Bo Whoop, a 1926 A. H. Fox Burt Becker side-by-side belonging to the writer T. Nash Buckingham, which was lost for more than half a century before being rediscovered. See Bo Whoop.

TO BEGIN WITH, DOUBLE NAMES ARE NOT middle names. Double names function as single names do—one is not to be spoken without the other. Middle names, on the other hand, are only used when you’re signing contracts or in big trouble. For example:

Kayla Jane, get your butt downstairs right this minute! That’s a middle name.

Hey everybody, Kayla Jane’s here! That’s a double name.

Double names are exactly what they say they are. They are one name, but two words. Like one cone with two scoops of ice cream on it.

Why do double names exist, and why especially in the South? Some explanations are even less meaningful than others.

1. Everything in the South is about heritage and family and family inclusiveness bordering on the insane. In some cases, a double name is derived from the single names of two people. Let’s say you want to name your daughter after your aunt Mary but don’t want to offend Aunt Lucille, so you’d name the daughter Mary Lucille. Not Lucille Mary, because that doesn’t sound right, and in most double names in which Mary takes part, Mary comes first. No one knows the why about that.

2. Double names point to the dichotomy of self, the bringing together of our inner lives and our outer presentation of self, the face we put on for others to see. I made that up.

3. It’s just something that happens. It is what it is.

Like chess moves, the variety of double names is infinite. Here are just a few: Alva Grace, Ida Bell, Jancy Jane, Olivia Faye, Oscar Ray, Joe Ben, Joe Don, Joe Jim, Joe Bill, Phoebe Lynn, Queen Anne, Sadie Bell, Sammie Lou, Twila Fay, and Zippornia Lee. I could go on, but after Zippornia Lee they let you down.

Here’s a true story. In high school I was in love with two girls at the same time and they were both named Mary. They were friends. I needed ways to differentiate between the two, even in my own head. This is where the double name came in handy. The double name made it easy, because one was named Mary Clayton and the other was Mary Catherine, which is much more elegant than Mary No. 1 and Mary No. 2. I ended up dating both of them, by the way, one after the other, but in the end neither worked out. Happy ending: two or three decades later, I met the woman who would become my wife.

Laura Anne.

(1890–1998)

“THERE ARE NO OTHER EVERGLADES IN THE world,” reads the famous opening line of The Everglades: River of Grass, a galvanizing book authored by a woman who had an intimate understanding of singularity. Marjory Stoneman Douglas fought unceasingly for the protection of South Florida’s natural resources, insisting just years before her death at age 108 that the urban ills that had infringed upon her beloved wetland network’s purity and span had not dissuaded her. “I say it’s got to be done,” she said of the Everglades’ defense. Born in Minneapolis in 1890, Douglas joined her father in Miami in 1915 after her husband proved to be a pauper and a cheat. Frank Stoneman, the editor of the town’s leading newspaper, assigned a gossip column to his daughter; within a few years, she was writing about the need for women’s suffrage and abolition of the convict lease system. Despite believing the Everglades was a buggy and unwelcoming swamp, she accepted an invitation to chronicle its natural and political history. The Everglades, published in 1947, is considered a masterpiece of environmental literature. Although she stood just five feet two, generations of activists have hailed Douglas as a giant, declaring that, if not for her pioneering work, there would be no Everglades left to save.

DESPITE THE SOMEWHAT UNSAVORY TERM, the Southern dove shoot is a fairly refined affair, part tent meeting and part camo-clad cotillion, an annual debutante ball of sorts for the hunting set. And while a dove shoot can take place on any day during the legal hunting season for mourning doves, it is the opening-day festivities that lend the term its real significance. It works like this: across most of the South, hunting season for mourning doves opens on the Saturday before Labor Day, which is preceded by a few weeks of brownnosing, chit calling in, and desperate glad-handing as hunters suck up to friends, colleagues, and distant family members for an invitation to a coveted shoot. It’s often a daylong affair. A pig pickin’ isn’t required but is nearly customary. Hunters spread out in cornfields and sunflower patches, hunkered down on five-gallon buckets with Labrador retrievers panting at their sides. Doves are notoriously challenging targets to hit, with an average ratio of far below 50 percent, and yet words of encouragement and support are rarely heard in the field. But the ribbing is all good-natured, and at the end there is often cold beer and homemade banana pudding to soothe any sunburn and bruised egos.

IS IT DRESSING IN THE SOUTH AND STUFFING in the North? Or is it dressing when baked in a pan and stuffing when baked in the cavity of a turkey? It depends on whom you ask, as both explanations have elements of truth. Stuffing, when prepared outside of the South, counts as a seasonal holiday treat. A buried treasure to be excavated from the Thanksgiving or Christmas turkey, it is limited by capacity, a bowlful gone until the following year. Dressing dresses a full table that holds a bounty of vegetables and side dishes. It may accompany turkeys, as well as chickens, ducks, and the occasional smothered pork chop, and consists primarily of cornbread (not bread), a tradition derived from making the most of stale leftover cornbread. Dressing is further prone to assuming the local accent of wherever it lands. It likes oysters near the shore and fruit in the mountains, and it never says no to a pecan.

THE TWENTY-FIRST AMENDMENT TO THE Constitution, passed in late 1933, repealed Prohibition after fourteen long years. While the federal government got out of the temperance game, the amendment left open a back door for local bluenose authorities. In the ensuing years, hundreds of counties declared themselves “dry” and prohibited the sale, consumption, and transportation of alcohol. Others became so-called moist counties, which may make exceptions for private consumption, sales in licensed clubs, or even the presence of a local winery. Some counties may be dry, but cities within them have voted to allow retail sales. It gets confusing. While dry counties are scattered throughout the South and, to some degree, the Midwest, many are concentrated in the states of Kentucky, Mississippi, and Arkansas. Interestingly, Lynchburg, Tennessee, home to the Jack Daniel’s distillery, is located within a dry county. So while you can tour the distillery, you can’t legally buy Jack Daniel’s in the Jack Daniel’s gift shop. Though you can purchase a special commemorative bottle that coincidentally comes filled with, you guessed it, Jack Daniel’s. Get it?

IT MEANS, SHE INSISTS (INCORRECTLY, AS IT happens), “white woods.” Blanche DuBois is Tennessee Williams’s most famous heroine: a fallen aristocrat come to live with her sister in the New Orleans slums of A Streetcar Named Desire, undone by her new status in life and brought to brutal conflict with her brother-in-law, Stanley. She’s caught between fantasy and reality, and the audience is never quite sure which one she should choose. See Williams, Tennessee.

WHILE DUELING WAS NEVER EXCLUSIVELY SOUTHERN in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century America, its most passionate and effective advocates were. Our nation’s Code Duello was published in 1838 by a former South Carolina governor, John Lyde Wilson. In other words, just a few scant years before dueling was outlawed in the mid-nineteenth century, Southern politicians were busy codifying the practice. Everybody who was anybody erred, and incurred a challenge. Never shy to whip out his sidearm, Andrew Jackson killed a rival planter in Tennessee after the neighbor made the mistake of accusing Jackson’s wife, Rachel, of being a bigamist and Jackson himself of cheating on a horse-racing bet. (The latter was most likely correct.) Jackson missed once but shot twice, killing his opponent, considered a huge, virtually criminal violation of etiquette by the men attending on the field. The future president escaped being prosecuted for murder.

Of New Orleans, the site of Jackson’s career-sealing military victory five years after that duel, it was said that you could face a morning challenge from a Creole aristocrat if you so much as moved the wrong chair at a dinner party without apology, or even with one. The court at Versailles was the model. Dueling was done under the live oaks out by the Bayou St. John. Salles d’armes, or fencing schools, were ragingly popular. The ruling late-eighteenth-century fencing master was Don José “Pepe” Llulla, a Minorcan said to be so adroit that he would indicate to his seconds on the field the exact button on his challenger’s waistcoat through which he would run his saber. Llulla engaged in some twenty-plus duels over a long life, preferring actually to use his superior talent to spare his opponents—he killed only two men. In the eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century South, that rated as excellent manners.

THE FRENCH INVENTED MAYO, BUT IT TOOK Eugenia Duke to perfect it, whipping up her own recipe to dress sandwiches she sold to World War I doughboys in Greenville, South Carolina. Duke’s is still eggier and zestier than other mayos, is still sold to fierce loyalists primarily below the Mason-Dixon Line, and still elevates a simple tomato sandwich into a memorable occasion. See Mayonnaise.

(1939–)

WIDELY RECOGNIZED AS ONE OF THE GRANDES dames of Southern cooking, Nathalie Dupree never refuses to pose for a picture with one of her fans. And she says the same thing every time she smiles for the camera: “Sex!” Born in New Jersey in 1939 (and a longtime resident of Charleston, South Carolina), Dupree has never shied away from subjects that make some people uncomfortable, including kitchen mistakes (she’s a vocal advocate) and the challenges of being a woman in the food-and-beverage industry. She started cooking in her college dormitory dining room, and—over her mother’s objections—trained as a chef at London’s Cordon Bleu school. In the 1970s, she opened a restaurant in rural Georgia, then founded the cooking school at Rich’s Department Store in Atlanta. She filmed her first cooking show in 1986 at the request of White Lily flour, and went on to become the first woman since Julia Child to host more than a hundred cooking programs on public television. She’s written fourteen cookbooks, including Mastering the Art of Southern Cooking, which won a prestigious James Beard Foundation Award. Although she lost her write-in bid for the U.S. Senate in 2010, she’s won countless lifetime achievement awards from organizations that include Les Dames d’Escoffier International, the James Beard Foundation, and the Southern Foodways Alliance.