UNLIKE ALMOST ANY RESTAURANT ON earth, Waffle House meets Robert Frost’s famous depiction of home as “the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.” It’s open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Waffle House is even better than your real home because they never get huffy about taking you in. The franchise’s commitment to staying open is legendary, to the point that the Federal Emergency Management Agency actually has an unofficial Waffle House Index. Green means that a given location is serving a full menu. Yellow means it’s open but has been forced to offer a limited menu. Red means that location has had to close. People who pay FEMA no mind whatsoever get scared at the news of a shuttered Waffle House, instantly tweeting that their local one is closed, meaning—actual quote here from a Floridian in the path of a hurricane—“shit’s about to get real.” The franchise was founded in 1955 by Joe Rogers Sr. and Tom Forkner in Avondale Estates, Georgia (the original store is now a museum where you can make your own waffle). The idea—a winner then, a winner still—was to combine the speed of fast food with sit-down service and twenty-four-hour availability. There is some debate about the name. Some say waffles were chosen because they were the most commonly ordered item. Others claim that they were the most profitable. We may never know. We do know and take comfort in the more than 1,500 stores in twenty-five states, the overwhelming majority in the South, where WH is a cultural icon. The layout—counter seats, booths, an open kitchen, and a jukebox—has remained constant, as has the two-sided laminated menu, featuring waffles, omelets, hash browns, biscuits, burgers, steaks, and pork chops. Its appeal cuts across all distinctions of race and class. There are people who’ve never been there sober or before 3:00 a.m. and people who’ve never been there for any meal but breakfast. There are meth heads and judges, families and tradesmen, travelers and locals. Our democracy should be so inclusive. The menu explains Waffle House shorthand, but regulars don’t need the menu to ask for what they want. “Covered” refers to cheese, “chunked” to ham, “smothered” to onions, “diced” to tomatoes, “peppered” to jalapeños, “capped” to mushrooms, “scattered” to spread and cooked crisply on the grill (this chiefly applies to the hash browns, which should always be ordered “scattered” and “well done”), and “all the way” means you want absolutely everything.

(1944–)

BORN IN 1944 AS THE EIGHTH AND LAST child of African American sharecroppers in Eatonton, Georgia, Alice Walker had an early life in the rural Jim Crow South that has fueled her books, short stories, and poetry—most notably her now-iconic 1982 novel, The Color Purple, which spawned an Oscar-nominated movie and a Tony Award–winning Broadway musical. Told in a series of letters by the main character, Celie, to God, and then to her sister, Nettie, the book weaves themes of sexism, racism, classism, violence, and sisterhood to illuminate the experience of black women, securing Walker the first Pulitzer Prize to go to a woman of color. In fact, Walker coined womanism—inspired by the Southern folk idiom “you acting womanish”—to describe feminists of color, a term still in use today. A longtime activist, from the civil rights movement to, controversially, her criticism of the Israeli government, Walker has also brought attention to important issues such as female genital mutilation, and almost single-handedly revived interest in Zora Neale Hurston by editing a 1979 anthology of the Florida-raised writer’s work. Walker’s own papers are now lodged with Emory University’s Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library in Atlanta, including a rare look at the budding talent of the writer as a precocious fifteen-year-old: a scrapbook of verse she titled Poems of a Childhood Poetess.

JOHN F. KENNEDY FAMOUSLY SAID THAT Washington, D.C., has all the efficiency of the South and all the charm of the hard-edged industrial Northeast. He meant it ironically, of course, but half a century later Washington is a thoroughly modern American city, with a functional subway system and a relatively well-heeled, youthful citizenry propelling its watering holes and music to new heights. Manners may not be exactly honeyed Georgian, but Washington is civil, and the vast, ambulatory bureaucracy better dressed than in Kennedy’s day.

Much of it is mounted on hybrid bikes or upholstered stools next to Gucci’ed lobbyists in craft cocktail bars, microbreweries, and José Andrés’s latest culinary invention. “D.C.” is now one of the country’s best cities for eats, as well as one of the wealthiest, its collective gaze directed upward not at faceless office buildings but at blue sky preserved by legal height limits and fringed with a cadre of mature trees that give the city a lovely, sylvan mien.

This habit of mixing nature with urban succor goes back to July 16, 1790, when the city was founded, with a unique 146-acre manicured lawn known simply as “the Mall,” gorgeous open space on some of the most valuable real estate on earth, lovingly cared for by the National Park Service. Here the world’s best collection of museums, like a prize dairy herd, feeds culture to twenty-five million tourists annually. The Mall set the historical precedent for physical openness and all-American optimism, and this endures.

Even though Washington’s eternally on the make—what national capital isn’t?—it manages to accommodate the ambitions of the world with remarkable ease and grace, regardless of who’s in the White House. The city’s designer, Pierre L’Enfant, a Parisian, daringly imposed upon the usual grid system of streets an overlay of diagonal avenues like the spokes of wheels that give Washington a touch of European sophistication. It also contributes to another Washington superlative: best walking city in America, in which the ambulatorily inclined can without too much effort find their happy way from the brick sidewalks of Georgetown to the apex of Mount St. Alban, where stands, in the midst of Frederick Law Olmsted’s commons, the inspiring National Cathedral, one of its steeples bristling with surveillance gear, for that, too, is Washington.

Likewise, Rock Creek Park, one of the nation’s oldest, splits the city north to south like a vernal wedge, affording endless trails and some old-growth oaks and beeches. Again the keeper of this vast natural preserve is the Park Service, unsung hero of the capital’s subtle blend of urban and wild, as all-American as the city itself.

(1913–1983)

THOUGH HE’S ACCURATELY CHRISTENED “THE father of modern Chicago blues,” Muddy Waters was born McKinley Morganfield in Issaquena County, Mississippi, earning his geographically evocative name from his grandmother because he, well, played in the mud all the time. In his non-puddle time, he began to play the harmonica by age five and spent the bulk of his childhood swimming in the sea of Son House, Robert Johnson, and Charley Patton, when he wasn’t working as a sharecropper and/or running a juke joint out of his house, which he usually was. He recorded with the musicologist Alan Lomax for the Library of Congress in 1941, and in 1943, the fire of his talents drove him to Chicago. From there, Waters went about burning up the city’s iconic South Side clubs and, with Chess Records, knocked the world off its axis with songs like “I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man,” “Mannish Boy,” “Got My Mojo Working,” and “Rollin’ Stone,” which made a big enough bang to inspire a band and a magazine. Before long, his electrified Muddy Waters Blues Band was setting the pace for Chicago blues and all subsequent rock and roll, blues-influenced or not; the basic noisy storm and thump of the style he crafted in the South Side remains a blueprint for any band with a guitar and a song about a lost woman (Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, and AC/DC all claimed Waters as a powerful influence). Waters died in 1983 with six Grammys to his name, as well as a claim to an immutable bedrock sound in American music.

(1923–2012)

I STEPPED OUT OF THE COLD AND INTO DOC Watson’s living room. It was a sunny day in the Blue Ridge Mountains, and there was still snow on the ground from a recent storm. I was thirteen years old—a kid with braces, skate shoes, and a limited appreciation of music. I knew of this legendary North Carolina folksinger and guitarist, who had played for presidents and won every award they give for making music. I had even begun learning one of his songs from my guitar teacher, but up until that point, my musical interests seldom reached beyond the artistic ventures of Kurt Cobain or Jimmy Page. So how did a kid still relatively oblivious to the history of American roots music find himself in the home of one of its most celebrated masters?

Wayne Hayes was a man who lived in my hometown of Concord, North Carolina. He was a local guy, a music lover, a songwriter, and a social studies teacher at the high school I would eventually attend. Around 1988, he wrote a song in honor of Doc’s famed son, Merle, who had recently passed away. He sent the song to Doc, a gesture that would prove to be the beginning of an enduring friendship. Wayne was also a friend of my father’s (it seems that in a small town, guys who play guitars and sing old country songs are bound to become friends sooner or later). They got together often in my dad’s wood shop or in whatever garage was available to talk, play songs, tell stories, and maybe have a cold beer.

Around 1993, Wayne asked my father if he’d like to visit Doc at his home in Deep Gap, North Carolina. Thankfully, Dad passed the invitation on to me. He figured this extraordinary opportunity would be more valuable for a young person, especially one with a few years of guitar lessons under his belt (or maybe he just saw an obvious advantage in the possibility of hearing something other than Nirvana’s Bleach blasting from the speakers in my bedroom). Doc was scheduled to play in Winston-Salem in a few weeks, and Wayne set it up for me to meet him during the day at his home, and to go to the performance with them that night.

I remember the experience of going to Doc Watson’s house in the same way one might remember a first day at a new school, or a first breakup, or the first time driving a car with no one else in it: an event when you know things will not be the same after this. My mind was about to be opened musically, and by someone esteemed and respected the world over, no less.

The nature of the visit and the surroundings were in no way glamorous. He appeared to live the relatively simple rural life that one might expect from his music. He lived in a modest home in a beautiful part of the state, in a friendly and uncrowded neighborhood near the Blue Ridge Parkway. We sat in his living room and talked about music. I remember Rosa Lee, his wife of forty-six years at the time, making something in the kitchen. She talked with me about their garden, about which vegetables had done well that year and which hadn’t. His daughter, Nancy, showed me around the house; I saw a hammer dulcimer for the first time, sitting in a small room that also happened to have six or seven Grammys on one wooden shelf. They had a couple of cats. I remember that when Doc opened the door by the carport, he somehow knew if they were there, despite his blindness. It was incredible. I recall thinking his hearing must be very different and clearly more advanced than mine. He let me play his guitar, and I showed him what little I had learned so far. He gave me some pointers. He gave me a pick. I remember feeling very calm, very at ease sitting and talking with him. So much of his character was right there, at the forefront of casual interaction: humility, knowledge, care, humor.

The performance that evening was at Salem College. Doc would be playing solo, and Wayne drove the three of us to the venue. We stopped and had supper at a K&W Cafeteria. I remember a swell of pride as Doc asked me to guide him into the restaurant. We walked slowly through the cafeteria line, his hand on my shoulder. I was nervous because I thought I might mess up somehow.

During the show, he played the song I was trying to learn at the time and, much to my amazement, mentioned me in his introduction—something about how there’s a young fellow in the audience trying to learn this one and that he’s doing a good job with it. I remember how clear his voice was, and how melodic his picking was, and how I, along with the rest of the audience, was completely rapt. I had never experienced a performance like it: simple in presentation, technically complex at times, highly professional, engaging, relatable, and vastly entertaining. He was funny and friendly and human and powerful but not in a way that I had ever seen before. In my mind at the time, “power” in musical performance was often synonymous with “volume” or even “aggression.” The power Doc had as a musician, and as a person, was not of the variety that required loudness. On the stage his ability to tell a story and to interpret a song so fully and with such a natural feel for melody was enough to draw the undivided attention of everyone in the room, no matter the size. Millions would have this experience firsthand throughout his eighty-nine years. His was a voice of unparalleled temperament, even and strong, graceful yet gloriously matter-of-fact. It truly was, and will remain, one of our classic American voices, rightfully in the company of Louis Armstrong, Hank Williams, Sr., Elvis Presley, Ella Fitzgerald.

In life, Doc was friendly and respectful to strangers, friends, family members, and fans. He exemplified patience, and brought joy and laughter to those with whom he came in contact. In conversation, he spoke and listened with interest, even to a thirteen-year-old kid from Concord.

Doc Watson changed the way I saw the acoustic guitar. He changed my understanding of how a song could be presented in sound and mood, and helped lead me to a uniquely rich tradition of music, a path of research and inspiration that continues for me daily. I am eternally grateful to this man who spent so much of his life sharing songs, and who was kind enough to share some with me all those years ago, on a clear day in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

I’M TOLD ONE OF THE PIRATES OF THE Caribbean movies involves ferocious killer mermaids, one of whom, for some reason, falls in love with a clergyman. I don’t think so, Hollywood. Mermaids have been set in stone for me ever since, as a boy, I saw a certain picture postcard: two beautiful women in tails, yes, and also in old-fashioned swimsuit tops, and their eyes have an unearthly gleam, and their lips are a brazen red, and their long fine hair floats filmily, driftily, spookily, above and behind.

And one of the mermaids is drinking what I took to be a Coca-Cola, and the other mermaid is eating a banana.

Underwater.

Ah, Florida! I grew up in Georgia, and I often tell people that Lady Gaga stands for that state twice. But Florida was the first state where I saw things that I knew were supposed to be exotic, and those underwater Flaflas still resonate with me. The postcard was from one of Florida’s earliest roadside attractions: Weeki Wachee Springs, off of U.S. 19 an hour or so north of Tampa. My parents took us to similar Florida destinations, such as Silver Springs, where we looked at fish and so on through a glass-bottom boat, and Sulphur Springs, where my grandfather soaked his rheumatism in murky water, but somehow we never made it to Weeki Wachee. Recently, at last, I did.

“Dancin’ and singin’ fish-tail women!” the loudspeaker blares, and there they are, moving and beaming, in crystal-clear emerald-tinted iridescent waters. We mermaid fanciers watch from a four-hundred-seat theater embedded in the spring’s limestone bank. We look face-to-face through glass at mermaids sixteen to twenty feet deep in seventy-two-degree water. When Weeki Wachee first opened, in 1947, there wasn’t much traffic on the highway. At the sound of an approaching car, mermaids would run out (taillessly) and lure it in with their siren calls. Weeki Wachee’s fortunes have waxed and waned since then. The Mouse, as Floridians often characterize Disney World, may have made actual human-scale mermaids seem small potatoes. To some people. Not to me.

“Mermaids go with bubbles like fairies go with wings,” says the promotional material from Weeki Wachee. Okay, it should be “as fairies go,” but who quibbles over grammar with mermaids? When a Weeki Wachee mermaid takes a sip of compressed air from a handy hose, she rises. When she exhales a bit, she subsides. “Gobs of bubbles” are produced either way. Fish are attracted to the bubbles. Mermaids interact with the fish. (I believe alligators are screened out, somehow or other, but there are photos of manatees swimming with the mermaids. Some people have speculated that the myth of mermaids arose from sailors’ sightings of manatees. If you’ve ever seen a picture of manatees and mermaids side by side—hey, who doesn’t love manatees, but come on.)

But now the bubbles are getting smaller, and smaller, and smaller. We have reached the point in the show when a single mermaid has headed down, down, way out of sight, into this bottomless spring, and the pressure is mounting, on her and on her bubbles, so we know it’s true, how deep she’s going. The air hose comes up, without the mermaid. They’re tiny now, her bubbles. She’s shooting for a descent of 117 feet, in ballet slippers. You try doing that without using your tail.

Seems like she’s been down there forever—two minutes and twenty-three seconds, by the clock. Time to reflect that more than 117 million gallons of water spring daily from the subterranean caverns whose bottom, if it exists, has never been touched. At last, she’s back! Just as chipper as you please. And boom: the whole view is all bubbles. Underwater, of course, there are no curtains, so when a Weeki Wachee show segues from scene to scene, stagehands set off a wall of bubbles. I’ll bet that if you have never been to Weeki Wachee, you have never seen so many bubbles at once.

And now we’re getting down to the iconic scene. Sure, fish eat underwater, but pretty girls? How can such things be? And yet it is happening, before our eyes. One mermaid is drinking from a bottle. It’s not Coke, I have learned from the Weeki Wachee souvenir booklet, because that drink’s carbonation “causes mermaid bloat” and throws off the bubble-balancing precision that dancin’ and swimmin’ at a given level in a five-mile-anhour current requires. It’s Grapette, which is less bubbly. Okay. I go way back with Grapette.

And another mermaid is eating an apple.

I expected a banana.

(1862–1931)

FIRST, THIS NATIVE OF HOLLY SPRINGS, MISSISSIPPI, took on a railroad conductor. Orphaned by a yellow fever epidemic, Ida B. Wells had in 1883 moved to Memphis to support her siblings by teaching school. While there, she ended up in a crowded train car where the conductor ordered her to give up her seat for a white man. Wells refused and bit the conductor’s hand before he and a porter dragged her out of her seat. Then, after becoming part owner of a black newspaper, Wells took on Memphis. After her friend Tom Moss was lynched in 1892 for defending his grocery store from a white mob, she wrote editorials urging blacks to leave the city. Her journalism so outraged white residents that they burned down her newspaper office. Wells relocated to Chicago, where she met and married Ferdinand Barnett on the third try: she twice postponed the ceremony because she was scheduled to give anti-lynching speeches. “I decided to continue to work as a journalist, for this was my first love,” she wrote. “And might be said, my only love.” Wells went on to help organize the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, cocreate the NAACP, and run for the Illinois legislature.

(1909–2001)

READ EUDORA WELTY. START WITH THE short stories. They’re sharp, funny, and deeply humane. I especially love her novel The Optimist’s Daughter, a meditation on memory and place, Southern style. Read every word she wrote—the experience will bring you to the taproot of the region.

Welty wrote in Jackson, Mississippi. After her education in the North and the Midwest, she returned to 1119 Pinehurst Street, where she spent her time gardening, participating in the intense social life of a Southern city, reviewing books, roaming the countryside photographing people. And writing from the heart of a place. She knew that where something happens is what happens. Her ear was fine-tuned to the local idiom. I love coming upon “a hold” and “I swan!” “I can just hear that,” we say as we read.

Southerners can small talk each other to death without a trace of boredom crossing anyone’s face. Welty captures cadence, the lulling storyteller voice, loops of lyric, then brings them up short by sharp declarative sentences—she used the tone of conversation without succumbing to talking, talking, talking.

Here’s what most of us never admit: Southerners are the most private people on the globe. Within tight interconnections of family, the real caring for one another, the incessant stories, the visiting, she’s onto the truth that all these rituals offer an elaborate continuity for solitary figures.

You can tour her Tudor Revival house and garden. When I visited, the word that came to mind was plain. Her desk and typewriter stand along the window wall of a bedroom. The house is colorless but full of books. Books everywhere, even stacked on the sofa. Walking through, I recognized: this was liberation.

Years ago, I happened to stand behind Eudora Welty in line at an airport shop. She was buying mints. Elderly and hunched, she counted out the change. As she turned, I said, “Miss Welty, I just have to say how much I admire your work.”

She snapped her purse and put her hand on my arm. “Well, thank you. You are just so sweet to say so.”

Her Southern grace abides in all her work.

Of the monumental twentieth-century writers—note that I do not limit my claim to Southern writers—she had the biggest heart. I insist: take a trip to your nearest bookstore.

WESTERN SWING MUSIC WAS BORN TO ACCOMPLISH one task: make the people dance. It grew up in Texas and Oklahoma as a rural answer to urban jazz and big-band tunes. The genre’s fathers—Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, the Light Crust Doughboys, and the Musical Brownies chief among them—drew on the quick tempos of swing bands, jazzy freewheeling improvisation, and the inclusion of decidedly country instruments (steel guitar, banjo, fiddle). At the dawn of the 1930s, dance halls across the lower Great Plains began to fill up, and by the late ’30s and into the ’40s, songs such as Bob Wills’s “New San Antonio Rose” had feet stomping across the country. Then, in 1944, during the heat of U.S. involvement in World War II, the federal government demanded a 30 percent tax be placed on “dancing” nightclubs around the country, and Western swing saw its popularity wane. It would be wrong, however, to say its influence saw the same fate. The sounds echo through rockabilly, honky-tonk, Southern rock, and modern country. See Wills, Bob.

IF ANY REQUIRED READING MADE YOU CRY your innocent guts out as a middle schooler, chances are Where the Red Fern Grows was involved. The book, which is set deep in the Ozark Mountains of Oklahoma, tells the tale of Billy Colman, a young boy determined to own and train a pair of coonhounds. Those hounds turn out to be Little Ann and Old Dan, arguably the most famous pair of hunting dogs in all of literature. Hard to imagine that if not for some good old-fashioned nudging, Billy, Little Ann, and Old Dan might never have graced the written page. The author, Wilson Rawls, set fire to his first draft of the novel, but, at the urging of his wife, rewrote the story. At last count Where the Red Fern Grows had sold more than six million copies—and engendered a river of tears—since it was first published in 1961.

AFTER THE ORRVILLE, OHIO–BASED J. M. Smucker Company bought the White Lily brand and closed its 125-year-old plant in Knoxville, Tennessee, in 2008, bakers were apoplectic. Southerners attribute near-mystical powers to the soft winter wheat flour. Biscuits would never be the same, they said. Milling White Lily in the Midwest? Might as well be distilling bourbon in the Napa Valley. Really, though, White Lily’s wheat has always come primarily from Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio. If anything, the flour is fresher than ever—and still deserving of its status as a household name in the South. See Flour.

SINCE IT BECAME TRENDY A FEW YEARS BACK, white sauce—a barbecue sauce firmly rooted in Alabama—has been featured in all manner of national magazines, which feel compelled to explain to readers just what they might do with the mayonnaise and vinegar blend. The diversity of suggestions conveys not just the versatility of white sauce, but also its overriding deliciousness: there is apparently no food too good for white sauce. It flatters french fries. It betters bluefish. It enhances eggs. And it cajoles chicken into tasting better than anyone thought chicken could taste. That’s the original application of the sauce, which is credited to Decatur’s Bob Gibson. Like his contemporary Duke’s Mayonnaise founder Eugenia Duke up in Greenville, South Carolina, Gibson had mayo on the mind in the 1920s; he debuted his sauce in 1925. It’s still served at Big Bob Gibson Bar-B-Q, although you’re likely to see it just about anywhere these days. And chefs across the region acknowledge Gibson’s visionary wisdom when they pair it with smoked chicken wings.

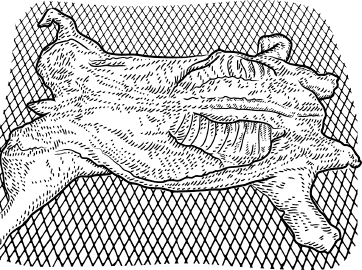

WHOLE-HOG BARBECUE HAS LONG BEEN THE house specialty at such revered joints as Skylight Inn BBQ in Ayden, North Carolina, and Scott’s Bar-B-Que in Hemingway, South Carolina. Its native range spans along the North and South Carolina coasts, where the practice of cooking entire pigs over coals dates back to colonial times. But a new appreciation for the endangered art has been taking it beyond its traditional boundaries. Whole hog is gaining ground at such new-guard spots as Buxton Hall Barbecue in Asheville, North Carolina, Martin’s Bar-B-Que Joint in Nashville, and way up north at Arrogant Swine in Brooklyn. Requiring wood coals, a pig-sized pit, and up to twenty-four hours of cooking, monitoring, and coal shoveling, it isn’t easy. But fans will tell you that the incomparable mix of white meat, dark meat, and crisp skin is worth the trouble. See Barbecue.

WHEN HERNANDO DE SOTO MADE LANDFALL on Florida’s southwest coast in 1539, he had in a ship’s hold thirteen sows he’d picked up in Cuba. (Those swine were most likely related to the pigs Columbus had released in the West Indies a few years earlier.) In a year, de Soto’s herd had grown to a reported three hundred pigs. And thus the die was cast. Sus scrofa’s unhindered embrace of the South has resembled nothing less than a bristly hide pulled across the region, wreaking havoc on crops, property, and native species. Wild pigs are now found in every Southern state, and in states such as Texas and Florida, seemingly behind every prickly pear and palmetto. In 1901, the nation’s uninvited pig herd was bolstered with an infusion of Eurasian wild boars when imported tuskers broke down a fence in the North Carolina mountains. Most of the pigs swarming swamps, timberlands, and even subdivisions are the progeny of animals free-ranged throughout the colonial period, and trapped and transplanted by hunters in more recent years. Given a reproductive rate that makes bunnies look practically chaste, wild pigs can be marginally controlled—and barbecued and grilled with tasty results—but they will never be vanquished. See Ossabaw hogs.

THE MOST INFLUENTIAL COUNTRY SINGER who ever lived—fans range from U2 to Bob Dylan to every budding musician in Nashville—Hank Williams (1923–1953) was a consummate storyteller, perfecting the tear-in-my-beer theme for generations to come. His thirty-five Top 10 hits include “Cold, Cold Heart,” “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” “Hey, Good Lookin’,” and “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” each of which populate jukeboxes all over the world. But Williams also suffered from crippling back pain, which caused him to drink heavily and take copious amounts of painkillers. His performances became uneven, and he made a habit of getting too far gone to play a show, which infuriated the Grand Ole Opry, leading to its revoking his membership in August 1952 after one too many slipups. Later that year, Williams died at age twenty-nine in the backseat of a car on his way to a performance in Charleston, West Virginia, with the cause of death determined to be heart heart failure.

Though his career was cut short, his legacy loomed large, especially to his son, Hank Williams Jr. Junior started his career by mimicking his father’s sound, but in the wake of the Outlaw movement began to incorporate Southern rock and blues, often collaborating with his good friend Waylon Jennings. Williams Jr.’s daughter Holly has recorded three well-received albums and has opened a clothing boutique, H. Audrey (named after her grandmother), in Nashville, and his son Shelton Hank Williams III is also a musician, having added to the family legend with marathon live shows that veer from classic country to thrash metal. A dead ringer for Hank Sr., Williams III has also led the charge for the Grand Ole Opry to reinstate his grandfather’s membership, releasing the song “The Grand Ole Opry (Ain’t So Grand)” in 2008.

(1911–1983)

“AMERICA ONLY HAS THREE CITIES: NEW York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everything else is Cleveland.” Contrary to popular opinion, Mark Twain did not say that: credit goes to Tennessee Williams. Thomas Lanier Williams III was born in Columbus, Mississippi, and moved to New Orleans when he was twenty-eight, taking on the name “Tennessee” by way of a fresh start. He forged himself in the licentious and bohemian French Quarter before becoming one of the most famous playwrights in American history with classics such as Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, The Glass Menagerie, and A Streetcar Named Desire. His plays are not happy places but rather are consumed by deep-rooted strife and repression, no doubt colored by his own unhappy family and the struggle of being a gay man in the early-twentieth-century South (he spent years in and out of mental institutions and wrestling with drug addiction before his death, in 1983). Still, there’s a certain image of him that endures, captivating in its own right—a man with a clean mustache and an immaculate tuxedo, sitting at some corner table at Brennan’s on Royal Street, pouring from a pitcher of martinis—and he’s become an indispensable part of New Orleans’ lore, with a literary festival held each spring in his honor.

(1905–1975)

JAMES ROBERT WILLS HAD A KNACK FOR getting folks on the dance floor. Born to a farm family just outside Kosse, Texas, Wills grew up on ranch-dance fiddling, a steady dose of blues (Bessie Smith was his idol), and jazz-style improvisation and solo play. He took that hodgepodge of influences and channeled it into a high-flying fusion that took over dance halls and jukeboxes from Georgia to California during the 1930s and ’40s. Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys commanded the stage with winding fiddle and steel guitar solos, an ever-present drumbeat, and Wills’s wisecracking brand of showmanship. The band didn’t take long to become the most popular Western swing act in the country, attracting crowds of dancers eager for a chance to move to the tunes of the King of Western Swing. See Western swing.

SOUTHERNERS HAVE HISTORICALLY PREFERRED cooked-to-death cabbage and collards, but a quick toss in a hot pan makes for a faster, more nutritious route to cooked greens. See Kil’t greens.

YOU KNOW SPRING HAS ARRIVED IN FULL force in the South when the tendrils of American wisteria—twisting counterclockwise up and around garden pergolas and wrought-iron fences—burst into cascading purple bloom. With varieties including the light-purple-flowering Kentucky wisteria and blue-flowering Texas wisteria, this beautiful backdrop for sipping sweet tea (or a julep) is native to the Southeast, growing well from Virginia to Florida over to Texas. Although American wisteria can spread up to fifty feet, it’s not as invasive as Chinese wisteria, which if left unchecked can, like in-laws at Christmas, quickly overtake your space, choking out the natives.

WHITE BREAD, PICKLES, AND ONIONS. IN brisket country, those freebies cost popular barbecue joints hundreds of dollars each week. Elsewhere, pit masters aren’t so generous. But you can usually at least count on a slice or two of Wonder Bread. Why don’t some of the country’s best barbecue masters pair their labor-intensive meats with the likes of skillet cornbread or hot buttered biscuits? For the same reason they serve canned beans and bagged slaw. They cook meat. Working without kitchen staffs, they’re already spending valuable time away from their main course when they drive down to the grocery store to load their sooty arms with the spongiest, moppingest white bread they can find. It’s a blank sheet for their fat-and-vinegar symphonies.

WHAT DOES THE EIFFEL TOWER HAVE IN common with the ornamental gates, fences, railings, and window grilles that decorate buildings throughout the South? The answer is all in the material: wrought iron, a low-carbon alloy prized by blacksmiths for its durability, malleability, and resistance to corrosion that lends cities such as Charleston, South Carolina, and New Orleans part of their charm. As the name implies, the metal is worked by hand (hence wrought) until its shape and form have been sufficiently manipulated to suit the metalworker’s, or his client’s, taste. During its heyday in the late 1800s and early 1900s, when blacksmiths such as Charleston’s talented and prolific Philip Simmons produced works that would later find homes in national museums, wrought iron was a symbol of prosperity. Alas, the material’s labor-intensive nature would eventually be its downfall, and by 1969, the last commercial wrought-iron plant closed its doors. Some wrought iron is still being produced today for heritage restoration purposes, but only by recycling scrap. See Simmons, Philip.