THE DENSE BLOCK OF FAT CARVED FROM A pig’s back presents many tempting options to the frugal cook. It can be cut into cubes and rendered into lard. Cured, it becomes salt pork, which seasons pots of greens, field peas, summer squash, and corn. Some cooks simmer it with vegetables and water until the fat softens and gives its porky essence to the potlikker. Others will fry it until crisp, leaving the liquid fat for the vegetables and snatching the golden-brown strips for snacking. Indeed, for many poorer Southerners, slices of cured fatback have long provided a less expensive alternative to bacon. Streak o’ lean, in fact, is a cut of fatback that looks like the mirror image of pork belly bacon: a white strip shot through with a wispy ribbon of pink meat. Cooks sometimes fry up these rashers after a soak in milk to leach out the excess salt, often coating them in flour before slipping them into a pan of hot peanut oil. After all, if you’re going to eat fried pig fat, might as well go whole hog.

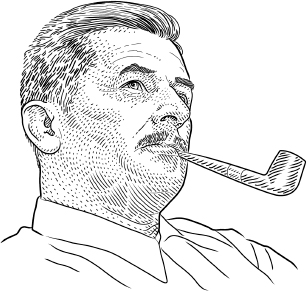

(1897–1962)

ARGUABLY THE GREATEST TWENTIETH-CENTURY American writer, and hands down the least finished, William Faulkner wrote novels, short stories, poetry, essays, and—when he needed the money—Hollywood screenplays. Influenced by James Joyce, he frequently wrote in a stream-of-consciousness style, previously unknown in this country, that confounded and repelled many readers. He didn’t care. Asked what he would advise readers who had slogged through one of his books two or three times and still didn’t understand it, Faulkner replied, “Read it four times.” In just fourteen years (1929–42), he produced ten novels and collections of short stories, including three novels frequently regarded as among the best ever written: The Sound and the Fury, As I Lay Dying, and Absalom, Absalom! By 1945, however, his novels were out of print. Much of his work is set in Yoknapatawpha County, a fictionalized version of Lafayette County, Mississippi, where he lived. Faulkner wrestled with questions of race, class, and the vagaries of Southern families. He wrote about the decay and tragedy of the South after the Civil War. But his dense prose was also compassionately alive to the humor, energy, and endurance of the human spirit. If you’ve never read him or have made frustrating attempts, try his 1942 collection of seven short stories, Go Down, Moses. It’s more linear. Faulkner is worth the whistle.

IN 2015, A FIELD-PEA TASTING TOOK PLACE in South Carolina. The table and sideboard in the dining room of a grand Charleston double house in the heart of the Holy City displayed Old Paris tureens and Limoges serving dishes filled with more than twenty varieties of the Southern staple, prepared in myriad ways. The tasting celebrated the diversity and the taste range of the legumes, named for the way farmers traditionally planted them at the edges of rice and corn fields to replenish nitrogen in the soil. Some varieties are also known as cowpeas, because harvesters left the stems, vines, and remnants of the crops for livestock to forage.

The black-eyed pea is undoubtedly the best known of the lot, but in fact there are hundreds of varieties: crowder peas, named for the way that they “crowd” the pod; pinkeyes, so called for their distinctively colored “eye”; and the genteelly named lady pea, to mention a few. Field peas, it would seem, have moved Southerners to waves of poetic fantasy, inspiring fanciful names like Wash Day, Mississippi Silver, Polecat, Turkey Craw, and Big Red Ripper. In color they range from light buff to deep burgundy, with spots, speckles, and eyes of different hues.

Field peas are thought to have originated in Africa, and few foods are more connected to African Americans. In their New World context, the peas are linked to enslaved African Americans but have been eaten in various ways throughout the South for more than three hundred years by Southerners of all stripes. No one knows exactly when or how they arrived, but prior to the early 1700s, they were growing at the edges of rice fields in the Carolina colonies before becoming one of the area’s first cash crops. Early American farmers, including George Washington, recognized their ability to improve the soil, and in 1797 he mentioned using them both as a crop and “for plowing in as manure.” They were in widespread cultivation in Virginia by 1800 and were called Indian peas there. They were grown in the slave gardens in Monticello, where Thomas Jefferson also used them as a field crop and experimented with new varieties. In 1798 he extolled their virtues, describing them as “very productive, excellent food for man and beast, [that] awaits without loss our leisure for gathering and shades the ground for the hottest months of the year.” They also appear in early cookbooks such as The Virginia Housewife, in which Mary Randolph suggests making a fried bean cake that is garnished with “thin bits of fried bacon.”

More than one hundred years later, George Washington Carver, through his work at Tuskegee Institute, encouraged farmers to use black-eyed peas to fix nitrogen in the soil. In 1903’s “Bulletin No. 5 Cow Peas,” he reminded them that “as a food for man, the cow pea should be to the South what the White Soup, Navy, or Boston bean is to the North, East, and West; and it may be prepared in a sufficient number of ways to suit the most fastidious palate.” He also published a second bulletin listing more than forty recipes including croquettes, griddle cakes, baked peas, and a cow-pea custard pie that seems to be a cousin to the Muslim bean pie. Carver didn’t have to tell anyone that field peas, especially black-eyed peas, come into their own on New Year’s Day. Whether solo, with greens (turnip, mustard, collard, kale, or even cabbage), or with rice as in South Carolina’s hoppin’ John, eating black-eyed peas or some form of field pea at the start of the year brings luck and prosperity. It is a tradition that few would dare to contravene.

A BACKYARD FLICKERING WITH FIREFLIES—better known in certain circles as lightning bugs—is as quintessentially Southern as lemonade on the porch. The winged beetles bring romance to the dusk, and not just figuratively: using the bioluminescence of their glimmering lower abdomens, they wink messages to potential mates.

Fireflies have long thrived in our temperate climate, at least until the kids get ahold of them; well before the advent of Day-Glo, preteens smeared them onto their T-shirts and ran around in the gloam glowing in the dark. The classic (kinder) method is to capture them in mason jars to create a makeshift lantern, or to just gaze out at them from the porch. The seriously committed hit the road, traveling to Great Smoky Mountains National Park near Elkmont, Tennessee (after booking parking spaces online months in advance), where thousands of Photinus carolinus—the only species in the Western Hemisphere that can synchronize its flashing patterns—put on a blockbuster mating-season light show for about two magical weeks, typically kicking off in late May.

Nowadays, firefly numbers are dwindling, perhaps because of development and light pollution. So if you want to attract them to your own little piece of paradise, cut the motion sensors and let nature’s fairy lights take over.

(1900–1948)

IT’S HARD TO FAULT PEOPLE FOR TURNING Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald into a symbol: her life was madcap and messy, making her the ideal warm-blooded representation of intangibles such as Jazz Age decadence and the destructive power of art. But before she was a cultural icon, she was a little girl in Montgomery, Alabama, admired for her pluck and good looks. Although her father, a state Supreme Court justice, was dour and straitlaced, Sayres and her pal Tallulah Bankhead liked to smoke, dance, and prance about in flesh-colored bathing suits. In 1918, she met F. Scott Fitzgerald, who was stationed at a nearby army camp. Two years later, he published his first book; the success of This Side of Paradise persuaded nineteen-year-old Zelda to accept his marriage proposal. The couple chased glamour from New York City to Paris but spent much of their time together drunk and unhappy. F. Scott Fitzgerald was baffled by his wife’s growing obsession with ballet, which wore out her body and mind; she was first institutionalized in 1930. Despite being diagnosed with schizophrenia, she arranged in 1932 for the publication of her fictionalized memoir, Save Me the Waltz. It flopped. Discouraged and mentally deteriorating, Zelda retreated further into her fantasies. She died in a fire in 1948 at Asheville’s Highland Hospital, where she was locked in a room, awaiting electroshock therapy.

A FLASK IS AN ESSENTIAL ACCESSORY IN A VARIETY of Southern social circumstances. While flasks come in many styles and materials—hammered pewter, polished silver, leather encased—all share similarly occult properties in that they can make a long and tedious occasion seem briefer, and a blissful occasion more prolonged and enjoyable. Examples of events that call for a flask include college football games (especially those in stadiums that prohibit alcohol or sell only overpriced beer); weddings of somewhat distant relatives where the quality of liquor is suspect; hunting trips with former college friends; and social gatherings involving your children’s current college friends.

A flask should fit a rear pants pocket or inside jacket pocket comfortably and invisibly. In appearance, it should reflect one’s personality—rugged, discreet, rakish, or what have you. For men, who now must grope their way through an era in which cuff links, tie clasps, decorative hatbands, and cigarette cases have become vanishingly rare, few accessories allow one to convey a sense of both style and status, and do so understatedly. A flask serves admirably; it should be chosen with care.

The contents of a flask are entirely a matter of personal preference, as long as one prefers a quality sipping bourbon.

YOU KNOW IT WHEN YOU SEE IT—USUALLY AT an old-time bluegrass festival. The fiddle and banjo really get cooking, and a few folks down front are compelled to abandon their seats for some open space. With their backbones straight and their arms hanging loose at their sides, their feet start slapping the floor in jerky sweeps. Knees jut up and out, but never too long before heels fly back down with force enough to add syncopation to the music. The enthralling effect suggests a marionette with strings attached only below the waist. Whether it’s called flatfooting, clogging, or buck dancing, it has been a dance form passed down by Appalachian settlers since . . . well, since there have been settlers in the Appalachians. It has roots in English, Irish, and Scottish folk dances but, this being America, also freely absorbed moves from minstrel shows and Native American ceremonial dances. Today trained groups flatfoot with fine-tuned choreography on big stages like the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville, North Carolina. But for many the real joy is in watching freestyle flatfooters channel traditional music to their toes and heels. Go ahead, join them. Just know that, as with most things having to do with mountain life, it’s harder than it looks.

THE FLEUR-DE-LIS DATES TO 1967, THE YEAR the New Orleans Saints football franchise was established. It has long been emblazoned on helmets, jerseys, banners, and bumper stickers, which are frequently flaunted to show one’s allegiance to “Saints Nation.” More recently, the fleur-de-lis has also become available as an emoji (Unicode U+269C).

Oh, all right, just kidding: the fleur-de-lis actually goes back a bit further than that. Lore has it that the symbol may date to an earlier epoch in Europe—perhaps as early as AD 400 and involving someone with the improbable name of Clovis. Or maybe AD 800, when Charlemagne was crowned emperor and took the symbol as his own. It is said to represent a stylized lily with three petals, and to symbolize purity. In the medieval era, the fleur-de-lis was reportedly adopted by the Bourbon dynasty and then came to be seen as the symbol of France, and by extension its colonial holdings, including eventually the city of New Orleans. Frankly, this all seems suspect, given that American football would not be invented for another half millennium.

WHEN THE FLORA-BAMA WENT UP IN 1964, the lounge’s position on the Florida-Alabama state line was a pragmatic solution to laws that prohibited liquor sales in the latter state’s Baldwin County. Now, though, the proudly tattered collection of drinking decks and live-music stages needs at least two states to contain the full slate of high-spirited fun on its calendar, which begins with a Gulf of Mexico dip on New Year’s Day and winds down with Santa Claus parachuting onto the Flora-Bama’s stretch of beach. (The bar’s renowned Interstate Mullet Toss comes around in the spring.) As Kenny Chesney describes the Hurricane Ivan survivor in his song “Flora-Bama,” “There’s ball caps, photographs, dollar bills and bras; license plates from every state nailed up to the wall.” Yet to fully appreciate the boozy charms of this good-time institution, which hosts honky-tonk church services on Sunday mornings, a few more accessories are required: namely, a pound of peel-and-eat Royal Red shrimp; a chocolate milk shake—esque Bushwacker, stiffened with five different kinds of liquor; flip-flops; and a Sharpie. You’ll want to scribble your name on a blank bit of wall, table, or rafter, since if you Flora-Bama correctly, you otherwise may not remember you were ever there.

IMAGINE YOU’RE ON VACATION. IT’S FLORIDA in the 1960s and you’re driving along Route 1. Suddenly you spot a young man parked on the side of the highway, his car trunk overflowing with lush oil paintings of idealized Florida landscapes. You pull over. The paintings—no more than twenty or thirty dollars apiece—pop from the canvases with life, depicting palm and poinciana trees in dream inlets under bird-filled skies of tropical pinks, oranges, and blues. They have an undeniable power. You buy one. And thus did it occur that thousands of paintings by the Florida Highwaymen—a group of twenty-six talented and entrepreneurial young African American artists who made their living this way in the Jim Crow South—ended up in homes across the country. Now their works hang in the White House, in museums, and on the walls of such luminaries as Steven Spielberg. Working in oil on industrial surfaces like Upson board, the Highwaymen produced paintings at such a rapid pace that Alfred Hair, the originator of the movement, was said to have started lifting weights just so he could keep painting long enough to keep up with the feverish demand.

SOUTHERNERS SPECIALIZE IN PIES AND BISCUITS for a reason. Our hot, sticky climate isn’t amenable to the high-protein wheats that grow out on the prairie and make hardy loaves. What thrives here is the more genteel soft winter wheat, which makes a low-protein flour that delivers light, flaky results—cake flour, in other words, rather than bread flour. Southern bakers are thus rightfully loyal to such homegrown brands as White Lily, Martha White, and Southern Biscuit, and more regional flours like Kentucky’s Weisenberger and South Carolina’s Adluh. See White Lily flour.

DECADES AGO, FOLKLORISTS TRAVELED UP into the Blue Ridge Mountains and down into the Mississippi lowlands in search of sounds they feared would be forever lost. More recently, scholars have started fretting about flavors—which are in many ways more challenging to document and disseminate than shape note hymns and work songs. The concern that contemporary palates might never get acquainted with the tang of sassafras tea, the sweetness of a rhubarb cobbler, or the rich grease of a freshly fried quail motivated students at Rabun Gap-Nacoochee School in Georgia to ask people living in North Georgia to recount their traditional practices, from dressing hogs to pickling cabbage. Those interviews formed the basis of Foxfire magazine, first published in 1966 and eagerly absorbed by back-to-the-landers. Eventually, a reverence for old recipes sparked an interest in heirloom ingredients, which were vanishing in the age of industrial agriculture. Prodded by chefs such as Charleston, South Carolina’s Sean Brock; food preserver April McGreger of Farmer’s Daughter in Carrboro, North Carolina; and grain evangelist Glenn Roberts of Anson Mills in Columbia, South Carolina, along with University of South Carolina professor David Shields, farmers in the 2000s started again cultivating formerly abandoned varieties such as Carolina Gold rice, Sapelo Island red peas, Bradford watermelons, purple ribbon sugarcane, and Seashore rye. See Foxfire.

(1916–2005)

THERE ARE HISTORY BOOKS, AND THEN there’s The Civil War: A Narrative, a sprawling record of the war by Shelby Foote, who drew on his own roots in the Mississippi Delta to pen his three-thousand-page masterwork. A novelist and fiction writer, Foote had been tapped by Random House to produce a short history of the Civil War, an assignment that expanded into a three-volume opus that commanded twenty years of his work life. Famously, Foote wrote everything in longhand with a dip pen, only going back later to type it all up. But while the trilogy won him acclaim, his fame came more from Ken Burns’s documentary The Civil War, a PBS smash that brought Foote’s Southern drawl, pipe, and personality into the living rooms of countless history buffs. Foote’s volumes have come to be considered definitive, and though critics claimed the series was light on the political and economic causes of the war, and cringed at his lack of footnotes, few could argue with the force of his narrative and the vividness with which he brought history to life on the page. See The Civil War.

LONG BEFORE THE DO-IT-YOURSELF MOVEMENT got self-styled urban homesteaders fermenting their own mead and pouring organic soy wax candles, residents of a tiny mountain community on the Georgia–North Carolina border distilled moonshine, warmed their hands over bubbling pots of hominy, and hand strung box banjos to entertain themselves on bitter cold nights. Trendsetting was the furthest thing from their minds, but the collected wisdom of the Foxfire folks remains influential decades later. Beginning in 1966, high-school students in Rabun County, Georgia, ventured out of the classroom to interview the elders of their mountain communities. The oral history project wound up becoming a social documentary on an epic scale, catalogued in more than a dozen best-selling Foxfire books now considered an invaluable archive of Southern Appalachian life and culture. More than fifty years later, Foxfire is a nonprofit with a museum and heritage center in Mountain City, Georgia, devoted to preserving Appalachian foodways and customs. “There are still people, both old-timers and new-timers,” the editor Kaye Carver Collins writes in the series’ most recent volume, “who believe in close-knit families, in kindness to their neighbors, and who take tremendous satisfaction in how they construct meaning from their corner of the world.” With help from Foxfire, that flame still burns brightly, and the torch keeps getting passed. See Food revivalists.

(1942–)

THE QUEEN OF SOUL, WITH HITS INCLUDING “Respect,” “Chain of Fools,” and “Think” woven into the fabric of American culture, Aretha Franklin has a fearlessness and sheer power that make even the strongest of her fellow singers seem tepid. Born in Memphis, she moved to Detroit at the age of four, honing her vocal and piano skills by traveling the country as part of her preacher father’s touring gospel revival show, befriending legends like Mahalia Jackson and Sam Cooke. Her list of hits continued in the 1960s and ’70s (the latter decade includes “Don’t Play That Song” and “Spanish Harlem”), before she hit a career lull in the late 1970s. But you can’t keep the Queen down for long: a part in the classic comedy The Blues Brothers gave her a career reboot, and she followed it up with two of her biggest hits, “Freeway of Love” and the international smash “I Knew You Were Waiting for Me” with the late George Michael. In early 2017, she announced her retirement after the release of a new album featuring Stevie Wonder.

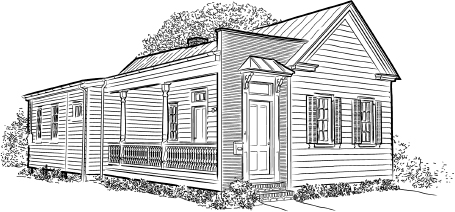

FREEDMAN’S COTTAGE IS THE SOMEWHAT MISLEADING term for a type of small, vernacular dwelling found in the Lowcountry, and especially associated with Charleston, South Carolina. More than a thousand were built throughout the Charleston peninsula from the 1860s to the 1930s, though many have been lost in the decades since. Like the Charleston single house, the cottage is only one room wide with a side piazza. It’s topped with a gable roof, but unlike the single house has no upper floors. The cottage’s narrow side typically faces the street, with a false front door opening onto the piazza.

Contrary to long-held belief, the cottages were not the exclusive domain of emancipated African Americans. More accurately called Charleston cottages, the small domiciles were popular among people of many ethnic backgrounds, including Irish and German immigrants. Built in rows and blocks of rows, they were often rented out to mill or phosphate-industry workers. They were cozy, typically 300 to 500 square feet and rarely more than 1,200 square feet. Though long underappreciated—and unprotected, because of their location outside official historic districts—Charleston cottages have become prized among historic preservationists and tiny-house lovers.

THE FRENCH 75 IS A SPIRIT-AND-CHAMPAGNE cocktail named after the 75-millimeter M1897, a fearsome field gun the French deployed during World War I. The name of the drink, it’s said, reflects its potent kick. Most recipes call for London Dry gin, lemon juice, and sugar, making the drink essentially a Tom Collins topped with champagne rather than seltzer. Lore suggests it was first served in Paris, at Harry’s New York Bar.

This is not, however, the universally preferred recipe. Chris Hannah, the head barman at the authoritatively named Arnaud’s French 75 bar in New Orleans, insists, with some logic, that anyone who makes a French 75 with gin is being willfully ignorant or unnecessarily adversarial. The French would not use the iconic British spirit, Hannah sensibly points out; they would choose to use their own spirit, which is to say cognac (or some other fine French brandy).

In truth, a French 75 may be made with either liquor, and both have merit. It’s best to try both and determine your own preference. Unless you’re ordering one at Arnaud’s French 75, in which case you order the gin variant at your own peril.

THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT STILL RECOGNIZES New Orleans as a municipality subject to the laws of the United States, and the city still posts representation to Washington. But its driving loyalties lie in fortifying its global renown for laissez-faire French-colonial excess—in the astronomical calorie count of its cuisine; in its innate fondness for any sort of business on the down low; in the hubba-hubba encouragement of casual sex and mistress-keeping in all social strata; in the routine elevation to public office of minor despots who are then just as routinely jailed; and, not least, in alcohol consumption. Three hundred years after its founding by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, the Sieur de Bienville, New Orleans’ ties to the social and legal fabric of the United States are gossamer at best. The French idea is bedrock.

The wellspring of that otherness is the postage-stamp-sized, ninety-two-square-block Vieux Carré. Literally the “Old Square” to the colony’s founding eighteenth-century Creole families, the Vieux Carré was the city. The square, as such, is the grid laid out at Bienville’s behest by Adrien de Pauger in 1721 on that slightly higher landing (elevation: one foot) tangential to the river. Aboriginally, it had been a portage point for the Houma tribe on their commute down Bayou St. John between the river and what became Lake Pontchartrain.

The French had staggering good luck in their choice of this portage. The Vieux Carré quickly became its own vastly rich, independent city-state, sitting astride a continent-spanning aquatic superhighway through the most fecund agricultural river delta known. Fortunes lay for the taking—on the backs of the thousands of slaves brought in by the French corsairs, of course. The town was second only to New York as an eighteenth-century market power on the continent. Indigo, rice, King Cotton, a robust slave market, warehouses along the levee, government houses around the Place d’Armes (now Jackson Square), and the glittering parties at the Philippe de Marigny mansion—these were the lodestones. The gilded age lasted just four generations, about eighty years, but long enough to cement an unassailable boomtown confidence in the city’s crazy-quilt DNA.

It stupefied the American envoys who arrived in France to buy it in 1803 that Napoleon would actually include New Orleans, and the rest of the huge territory, in his fire sale, but he had expensive wars still to lose. There was, instantly, a business war between the old Creoles and the Anglo-Saxon usurpers. The more-than-slightly derogatory sobriquet “French Quarter” came into play after the American influx, just as the old Creole families derided “the American city” springing up below Canal Street.

The section has had many masters. Not one of them ever quite managed to bend the Quarter to whatever he had in mind—neither the French, nor the Spanish, nor the super-crusty wheeler-dealer Andrew Jackson, nor the infamous 1930s governor-demagogue Huey Long, nor the dapper and deadly Mafia don Carlos “the Little Man” Marcello, who remains on the short list as a mastermind of the JFK assassination. Eros and Thanatos danced their own jig in this original corner of New Orleans, under the thumb of no man.

The Quarter lost its long, slow battle against the American takeover, but became along the way a neighborhood of pirates—literally and metaphorically. Any attempt to mess with or, worse, legislate any business or social curlicue in the Quarter usually backfired. A backward American “foreign” trade embargo in 1807 led the privateer brothers Pierre and Jean Laffitte (later Americanized to Lafitte) to establish their “free city” of Barataria downriver, fencing contraband goods and luxuries back in the Quarter. Trying to banish prostitution from the Quarter in 1897, a Sisyphean project from the get-go, city fathers gerrymandered it two blocks west, along Basin Street to Storyville (later Tremé)—the birthplace of Louis Armstrong to a prostitute mother in 1901. But the concentration of brothels—Mahogany Hall was the most opulent—brought enormous custom, which brought bars, which brought musicians. And so the aldermen accidentally manufactured precisely the rich cultural loam in which the fathers of American popular music—Kid Ory, King Oliver, Lawrence Duhé, Sidney Bechet, and the young Armstrong—could grow their great gift of jazz. When Storyville was shuttered in 1915, the prostitutes moved back to the Quarter with no fanfare.

People washed up like flotsam, for many reasons, but mainly because the place was both insular and forgiving. During Prohibition—which in New Orleans was regarded more as a bizarre joke staged by clinically insane people in a faraway country than as legislation pertaining to real life—one young part-time worker on a Lake Pontchartrain bootlegger’s boat was William Faulkner. By 1925 he was penning Soldier’s Pay, his first novel, in the little house at 624 Pirate’s Alley, just off Jackson Square. Later in the century, Tennessee Williams took up the mantle of the New Orleans writer, spending years in the Quarter—cane, great panama hat, and all.

Since the invention of jazz a century ago, the Quarter has served America as an ad hoc sensory-rehabilitation clinic for hordes of pilgrims—about ten million per annum—from the sadder monochromatic corners of the country, who visit inchoately yearning for something different to see, hear, eat, and drink.

There, they get it.

FRIED CHICKEN WAS ONCE A LUXURY. CRISPED in a bath of bubbling fat by those sought-after cooks who could deliver a golden crust and tender meat from a heavy cast-iron skillet, it came to the table only on the occasion that a family managed to finagle a tender spring chicken. The tough old chicken-and-dumplings birds laying eggs in the coop out back wouldn’t do. In 1952, everything changed. That was the year the first KFC franchise opened in Salt Lake City. More important, though, it was the year when a growing population of mass-produced young birds finally overtook those older laying hens as the country’s most popular poultry. Chicken prices plummeted. Deep fryers proliferated. Southerners didn’t lose their respect for proper skillet-fried bird, though. Today fried chicken is a dish for all occasions. Under a gas-station heat lamp, it’s late-night salvation. On a fast-food biscuit, it’s a hangover-busting breakfast. From the grocery-store deli counter, it’s a make-do lunch. And in white-tablecloth restaurants, it comes artfully fried in heritage fats and garnished with sprinklings of delicate herbs. Like a devilish debutante with a trunk full of camo and cheap beer, fried chicken today straddles the high and the low with grace—and grease.

THE PICKUP TRUCKS IN FRIED GREEN TOMATOES, the 1992 movie based on a Fannie Flagg novel, were definitely Southern. And to Northern audiences, the shotguns and Klan references seemed pretty Southern, too. So it stood to reason that fried green tomatoes must be an iconic Southern dish. Prior to 1992, though, when anyone ate green tomatoes at all, it was early-frost-afflicted Midwesterners, who may have been influenced by Jewish immigrants who came from old-world places where people commonly pickled them. Southerners generally preferred to let their ’maters ripen so they could slice up the bright red fruit for sandwiches. But once the movie achieved blockbuster status, savvy Southern chefs decided to profit from the myth. Within the year, the dish was so widespread that Flagg heard its popularity had disrupted the region’s tomato market, much like what Sideways would later do to pinot noir. Condemned to careers of frying green tomatoes, chefs in cities hailed for their Southernness, such as Charleston, South Carolina, and Atlanta, now do their best to reinvigorate the dish with sophisticated sauces and fresh seafood. Usually, though, the tomatoes end up plated with pimento cheese.

NO, IT’S NOT REALLY A PIE—MORE LIKE A junk-food lunch in a bag. The recipe is uncomplicated: tear open a one-ounce package of Fritos, ladle some chili right into the bag, top it with grated cheddar and chopped onions, and go to town with a plastic spork. That’s Frito Pie, the high-school football concession-stand classic that Southerners love and Northerners misunderstand. On his TV series, Anthony Bourdain once compared a freshly made Frito Pie to a warm colostomy bag. Maybe he would have taken to one of the many upscale restaurant versions—such as a fine-china soup bowl full of corn chips covered with venison chili and topped with goat cheese and chopped Vidalia onions. Also known by Tex-Mex aficionados as a “walking taco,” the Frito Pie has given rise to less highfalutin spin-offs as well, including the Cheeto Pie, made by layering chili into a bag of . . . you guessed it.

FROGGING—OR FROGGIN’, IF YOU HAVE A Cajun outdoors TV show or want to sound as if you might—is the hunting of wild bullfrogs. The practice is particularly popular in the Deep South where French influence is more prominent. Froggers go out at night in jon boats or other shallow-draft craft. Serious froggers wear hard hats to which they attach powerful sealed-beam headlamps that connect directly to a motorboat’s 12-volt battery. (They prefer aircraft landing bulbs—such as the GE 4405 or H 4405—over automobile lights, which cast a more diffuse beam.) Frogs freeze when illuminated. It is not known whether the light blinds or otherwise paralyzes them or whether they are simply overconfident about their natural camouflage. Froggers gig their prey with pronged forks on poles or grab them by hand—the latter having the advantages of keeping the frog alive and saving money on ice. Frog eyes reflect whitish yellow in the light’s beam, while the eyes of alligators—which are also out hunting frogs at night—show up red. You don’t want to grab anything with red eyes. A good-sized frog can match the size of a rotisserie chicken and weigh two pounds, though most are in the one-pound range. They don’t taste like chicken. They taste like frog and are delicious.

YOU WON’T FIND ANY FROGS IN FROGMORE stew, a Lowcountry classic with origins in the Gullah Geechee community of Frogmore on South Carolina’s St. Helena Island. Nor is it a stew by most definitions. You don’t slurp the one-pot boil out of a bowl. Traditionally, you scoop it by hand off a newspaper-covered table onto which a cook has heaped the imposing piles of shrimp, corn on the cob, sausage, and often potatoes and onions. It’s a coastal celebration of summertime that feeds a crowd without much trouble. Be sure to add plenty of seasoning to the boiling water, and don’t dare sully this bare-bones feast with seafood that’s anything less than superfresh.