(1925–1964)

IN NEAR-PERFECT PROSE, FLANNERY O’CONNOR wrote about some very odd people doing some very odd things—in other words, real life in the American South. Marked by dark humor and infused with her deep Catholic faith, O’Connor’s short stories are widely considered some of the finest ever written. The Complete Stories, published posthumously, won the 1972 National Book Award and included such classics as “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” “Good Country People,” and “The Life You Save May Be Your Own.” O’Connor also published two novels—Wise Blood (1952) and The Violent Bear It Away (1960)—but she is best known for her stories. Born in Savannah, O’Connor moved to Milledgeville, Georgia, where she lived on her family farm, Andalusia. She studied at the famed Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where, because of her strong Southern accent and intense bashfulness, the legendary director Paul Engle reportedly read her stories aloud to the class for her. Lupus killed her father when she was fifteen, and in 1951 O’Connor was stricken by it, too. She returned to Andalusia, where she lived the rest of her short life with her mother and several peacocks, the descendants of which still roam the grounds today.

WHEREVER YOU FIND THE KIND OF CULINARY repertoire Italians call la cucina povera (cooking of the poor), there will be a local taste for offal—the organ meats and other squidgy bits that typically count as a by-product of butchery. Slaves of the antebellum South and then the poor country folk, both black and white, knew that the lower you ate on the hog, the tastier things got. Southern foodways encompass a vast tradition of offal cookery, from fried pig ears, to chitlins stewed with vinegar and hot sauce, to head cheese. Traditionally, the best time to eat variety meats was right after the annual hog killing on a farm. Kidneys, lungs, liver, and hog maws were perishable and needed to be processed and cooked quickly. Other offcuts could then be preserved—the feet pickled, the skins and fat cured. Organ meats have lately become a hallmark of Southern revivalist cookery, and rare is the badass chef who does not try his or her hand at fried pig tails and souse. The regional taste for offal doesn’t limit itself to pork: throughout the South, diners display a prodigious appetite for chicken gizzards, livers, and hearts. See Gizzards.

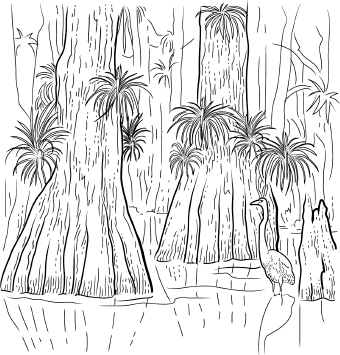

IT’S BEEN SAID THAT IT WAS ONCE POSSIBLE for a man to hike the entire way across North America’s largest swamp—thirty-eight miles north to south, twenty-five miles east-west—by stepping on the backs of alligators. A Southern whopper, granted, but it’s a lively one. Long a refuge for those seeking to disappear, Okefenokee sprawls seven hundred square miles, straddling the Georgia-Florida border. Early Native Americans called it the Land of the Trembling Earth, and it’s not hard to grasp why the swamp became a fortress for the followed. It’s inhospitably stunning. A deafening hum of cicadas fills the air, and the black-water current hardly moves. Bald cypress and swamp tupelo branches haunted with Spanish moss frame the sky of this wonderland of old-growth timber stands, spongy islands, flooded prairies, and other habitat niches that shelter hundreds of species: Florida black bears, endangered red-cockaded woodpeckers and wood storks, sandhill cranes, ospreys, otters, bobcats, and more than twenty species of frogs and toads serenading swamp visitors. While some areas allow motorboats, the primary mode of transportation remains as it was when native tribes navigated its dark waterways, the paddled canoe—some 120 miles of canoe trails crisscross the refuge—and conservationists aim to keep it that way. In 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 7593, legally protecting and creating the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge, setting aside the swamp as an intriguing place to vanish, however temporarily, for many adventurers and fugitives to come.

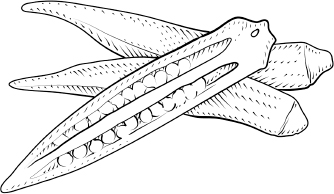

THE STORY OF OKRA IS A LONG ONE. A quintessentially Southern food, as the chef and author Virginia Willis describes it in her eponymous cookbook on the subject, it seems as Southern as field peas and collard greens. It has long been demeaned for its sliminess, and at times marginalized as one of those “Southern things.” But cooks knew it far outside the South, and most likely for thousands of years, before a single green pod ever reached these parts.

A relative of both cotton and hibiscus, as its delicate flower suggests, okra had its beginnings, scholars believe, in equatorial Africa, in the Sahel region south of the Sahara, ranging from Mali eastward to Ethiopia. Cooks there prize it as a thickener as well as a vegetable, and it appears in a continent-wide array of dishes, among them Egypt’s bamia (an okra stew that can be prepared with lamb or beef or served as a vegetarian side dish) and Senegal’s soupikandia, a soupy stew that is an ancestor of gumbo. Indeed, the word gumbo is a corruption of the words for the vegetable in the Bantu languages of Central Africa, tchingombo and ochingombo. (To this day, anyone who wants okra in any French-speaking region need only ask for gombo.) From the continent’s midsection, the plant made its way to Mediterranean shores—first cultivated in Egypt perhaps as long ago as 2000 BC—before winning hearts and stomachs in the Middle East and beyond. It is prized as bhindi, or lady’s fingers, in India.

No one is sure exactly where, when, or how okra made its way to the Western Hemisphere, although enslaved Africans generally get credit. There is evidence of the plant in Brazil in 1658, and it most likely arrived in the southern United States via the Caribbean. It reached Louisiana in the early 1700s, and also appeared in Charleston, South Carolina, early on. Thomas Jefferson noted its cultivation in Virginia before 1781 (and planted it in his own gardens at Monticello in 1809, after his presidency). By 1824, it was well known enough to appear in several recipes in Mary Randolph’s The Virginia Housewife, the most notable of them entitled simply “Gumbs: A West India Dish”—steamed okra pods served with melted butter, which Randolph deemed “very nutritious and easy of digestion.” Jefferson’s family had okra recipes that were soupy stews containing ingredients such as potatoes, squash, onions, lima beans, parsley, and occasionally tomatoes. Bacon was used for seasoning, and chicken was added later, as were veal, corn, and green peppers. The results probably resembled a Charleston gumbo more than a Louisiana one.

It seems that no one lacks an opinion about okra. Admirers praise its thickening abilities and versatile flavor; detractors cannot get past its mucilaginous properties. The vegetable can be fried, steamed, stewed, boiled, pickled, and even eaten raw or blanched in a salad. It is especially prized, though, as the thickener for soups and rich gumbo of the type served in South Louisiana. These days, okra is also gaining acceptance beyond the South, as chefs and cooks throughout the country discover its versatility through myriad international and Southern recipes and find new uses for the pod that is one of Africa’s gifts to the cooking of the New World.

LONG KNOWN BY COOKS AND CONSUMERS alike in the Chesapeake Bay region as the “third spice” (right after salt and pepper), this popular crab seasoning has expanded across the country and beyond, particularly in the South. It’s used to flavor everything from pasta to pumpkin seeds, beer to Bloody Marys, chocolate to Cheetos. Most of these pairings should be avoided like bad oysters, but the stuff is surprisingly addictive on shellfish, french fries, Tater Tots, corn on the cob, boiled peanuts, hard-boiled eggs, and even—in moderation—cantaloupe. A German immigrant spice merchant named Gustav Brunn first marketed his invention in 1939, under a name that sounds as if it were calculated to arouse suspicion: Delicious Brand Shrimp and Crab Seasoning. He couldn’t give the stuff away. Before long he changed the name to Old Bay, after the Old Bay Line of steamboats that operated on the Chesapeake between 1840 and 1962. It took off and never looked back. The cult of Old Bay defies rational explanation. There are T-shirts displaying the iconic yellow, blue, and red tin with captions like “’Tis the Seasoning,” “Old Bay Picking Team,” and “I Put Old Bay on My Old Bay.” There are Old Bay tattoos and Old Bay–flavored ice cream. In 2013, the company released a commemorative can featuring six players from the Baltimore Ravens to celebrate the team’s Super Bowl victory. In 2014, Maryland’s Flying Dog Brewery released the seasonal Dead Rise Old Bay Summer Ale, featuring citrus hop notes, a crisp, sharp finish, and a dash of Old Bay. It withstood initial skeptics and is still available May through September in the mid-Atlantic.

THE OLD-FASHIONED IS A WHISKEY COCKTAIL that has been old-fashioned since the late nineteenth century. H. L. Mencken once rightly called it “the grandfather of them all.” It’s essentially the original cocktail. Early topers found that the taste of spirit—whiskey, brandy, rum, whatever—slightly adulterated with a bit of sugar and a few dashes of bitters (which were originally dispensed as medicine) made for a fine way to begin the day and ward off various forms of unpleasantness: disease, dry mouth, foul mood.

As with many drinks, the old-fashioned grew to become an evening libation. When drinkers in the latter half of the nineteenth century started ordering blasphemous cocktails that mixed wine and spirits (e.g., the martini, the Manhattan), purists were aghast and insisted on ordering an “old-fashioned whiskey cocktail.”

Over time, the drink has suffered from gradual debasement. It went from being a simple, austere, and elegant cocktail, perfectly balanced, to one that became a vector for various and sundry fruits—oranges and overly red maraschino cherries, in particular, have been pulverized in the bottoms of glasses and abandoned there as if in a tableau of pomicultural carnage. James Beard once aptly said that he liked his “old-fashioned without any refuse in the way of fruit.”

Also, some believe a splash of club soda will always improve an old-fashioned. These people are no doubt wrong in many other life choices as well.

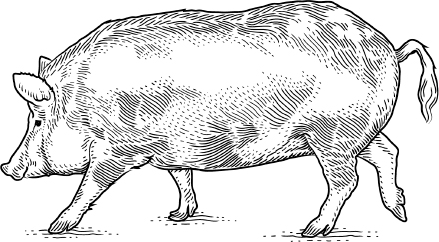

AFTER EITHER BEING RELEASED OR ESCAPING their captors in the sixteenth century, hogs on Georgia’s Ossabaw Island got smaller and smaller and smaller. Their significance, though, has only increased. Because the feral hogs couldn’t roam beyond the boundaries of the 25,000-acre Sea Island to which Spanish explorers brought them, they retain most of the characteristics of colonial pigs, even if they weigh a relatively dainty two hundred pounds. That’s made them hugely popular with Southern historic sites such as Colonial Williamsburg, Charleston, South Carolina’s Middleton Place, and Mount Vernon, which are reluctant to confuse visitors by exhibiting the pink, vaguely rectangular pigs that are standard on American farms today. Ossabaw hogs, by contrast, are black and round, with thick coats and long snouts. What visitors can’t see is how Ossabaws taste: the hogs have dark, fatty flesh that’s been likened to jamón ibérico, although it performs just as well in the Southern context when roasted or smoked whole. Although the hogs continue to thrive on Ossabaw, only about two hundred of them live on the mainland, earning them endangered status. See Wild hogs.

IN THE EARLY 1970S, POWER PLAYERS ON Nashville’s Music Row began insisting on a more radio-friendly country-music sound, one featuring pop melodies and lush, sweeping string arrangements from artists like Charley Pride and Conway Twitty. Other musicians, such as Kris Kristofferson, Willie Nelson, and Waylon Jennings, could barely hide their disgust, with Jennings famously saying that he “couldn’t go pop with a mouthful of firecrackers.” But as much as outlaw country meant a rawer sound, it was just as applicable to the artists’ way of doing business. Nelson and Jennings, along with cult figures such as Tompall Glaser and Bobby Bare, insisted on complete control of their recordings, something unheard-of in the Music Row hit-making machine. And they backed up their chutzpah: the 1976 album Wanted! The Outlaws, a compilation that featured songs from Glaser, Nelson, Jennings, and his wife, Jessi Colter, became the first country album to go platinum, selling more than a million copies. Four decades on, the outlaw spirit is alive and well. Sirius XM satellite radio has a catchall Outlaw Country channel, and renegade artists such as Chris Stapleton, Jason Isbell, Sturgill Simpson, and Margo Price continue to carry the torch.

SOMETHING DRAWS US HERE, WHETHER IT’S the connection to Faulkner, a nationally known bookstore, or the many bars that surround the town square. Mention Oxford, Mississippi, and people ask about the literary scene. Can you throw a stone in any direction and hit a writer? Do y’all talk about writing at the bars? How tall is John Grisham?

We actually have so many professional novelists, screenwriters, poets, and essayists living and working in Oxford that trying to name them all would be a disservice to those I might forget. And while I see several writer pals around town nearly every day, we seem to talk everything else but shop. Mostly, we go to movies. As far as John Grisham’s height, I’ve never met or seen him, as he left town nearly twenty years ago, a little before I arrived.

For me, most of the draw comes from Oxford’s past. The famous four—Faulkner, Willie Morris, Larry Brown, and Barry Hannah—have all passed on. Those guys, two of them great pals, were what brought me here. I had the honor of drinking many beers with Larry, the master of Southern grit, sometimes with a shot of god-awful Rumple Minze, and hanging out and shooting pistols and rifles with Barry, a master of short stories who wrote in wild and rhythmic ways. Barry loved guns, motorcycles, and noir. He also loved telling tall tales. He once introduced me as “the best goddamn fighter pilot I’ve ever seen.”

Neither one of us could fly a plane.

When the late Dean Faulkner Wells released her memoir, Every Day by the Sun, the story of growing up as Faulkner’s favorite niece, she drew on the strength of Oxford’s literary friends. Famously shy, she was terrified of reading from her book at the big release. So a handful of writers sat onstage with her, and we read her words while she listened with everyone else. Everyone loved Dean. She and her husband, the novelist Larry Wells, often hosted literary salons at their house, especially when visiting authors came through town (Faulkner had edited Absalom, Absalom! on their dining room table, a fact that caused most visitors to swoon). For many of us, Dean made “Pappy” more than just a statue and a face on a postage stamp. Through her, he was the real person who told ghost stories to the kids at Rowan Oak and refused to take phone calls during dinner. She didn’t even realize he was famous until she walked down the street with him in Paris, drawing stares and whispers.

To my great regret, I missed Willie Morris by one year. He moved just before I arrived in town. But the stories Dean, Larry, and his many other friends told about Willie were legendary. I can’t drive past the city cemetery without thinking about the night he covertly buried his beloved Lab, Pete, somewhere not far from Faulkner’s grave.

As for the living, you can find most of us at local watering holes, bourbon being our common denominator from Faulkner on. We’re bonded by the beauty and grit of this place—which makes for great material—and its sense of noir. From Faulkner’s Sanctuary to Larry’s Father and Son to Barry’s Yonder Stands Your Orphan, there’s a darkness in most of our work, fueled by bourbon and the hardscrabble landscape outside the oasis of the quaint square, with the old white courthouse surrounded by brick storefronts.

I don’t believe anyone would dispute that the heart of the literary scene is Square Books, a storied shop that’s brought an endless lineup of all-stars since Richard and Lisa Howorth opened it in 1979. Most Thursdays you can find a nationally known writer speaking during the weekly Thacker Mountain Radio Hour, an hour of literature and music with roots in the traditional Southern medicine show. Afterward, you can usually find the local writers welcoming the visitor. Drinks flow freely.

I once heard a visiting writer ask Richard Howorth what brings so many different voices here to work. Is it Faulkner? Or has it grown into something more? Howorth thought about it for a moment, then paraphrased a line from Casablanca: “I think they come here for the waters.”

AMERICA’S OYSTER, CRASSOSTREA VIRGINICA, used to live in such abundance in the Chesapeake Bay, Atlantic estuaries, and the Gulf of Mexico that it could feed a nation. During decades of railroad expansion, the oysters traveled across the country, packed in ice and sawdust, bound for upscale bars and taverns. Prohibition put an end to this trade, and oyster bars faded from every region except the South. New Orleans oyster houses, with their nimble and fast-talking shuckers, never went anywhere. Nor did the seafood shacks of the coastal South, which kept a kind of raucous American oyster bar culture alive. Recent years have seen both a decimation of wild oyster populations, due to overharvesting and environmental degradation, and a resurgence of oyster bars throughout the country, thanks to advances in “off-bottom” shellfish cultivation. Southern oystermen—particularly those around the Chesapeake and Mobile Bays—have lately joined the boutique oyster party. Their hand-harvested product may not have the mouthful-of-pennies brininess of Northern cold-water oysters, but they have a soft sweetness all their own.

COME AUTUMN, THE DECIDUOUS FORESTS that blanket the central United States’ Ozark highlands explode in a crimson-yellow-orange riot to rival the most vibrant Vermont tableau. Encompassing forty-seven thousand square miles spread over four states—Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma—the region (technically, a large plateau rather than a mountain range) is awash in clear, bubbling streams and breathtaking vistas. Rainbows appear almost daily. Early arrivals, mostly explorers and the Scotch-Irish immigrants who settled here during early-nineteenth-century land grabs, were daunted by the high, rugged ridges, steep hillsides, and treacherous passes. But later travelers sought out the Ozarks’ tamer features, such as the “healing waters and springs” that made Eureka Springs, Arkansas, a fashionable turn-of-the-century spa destination. As a result, the region lays claim to an eclectic mix of people and cultures, from Native Americans and New Age spiritualists, to back-to-the-land types and sustainability-minded developers, to an impressively mismatched range of high-profile figures: George Washington Carver, Paul Harvey, Langston Hughes, and Brad Pitt are all native sons.