SOUTHERNERS TAKE TABASCO FOR GRANTED—until one day we find ourselves in front of a plate of fried eggs in an airport coffee shop in the Maple Syrup Belt with none to be had. Since its invention by Edmund McIlhenny, in 1868, the Louisiana hot sauce made from fermented Tabasco peppers has become a worldwide phenomenon. In the heyday of nineteenth-century American and British oyster culture, devotees considered it the ultimate condiment for oysters on the half shell—an early advertisement, in fact, featured an illustration of a Tabasco bottle emerging Venus-like from an oyster shell. In 1885, British soldiers carried bottles of it at the Battle of Khartoum, in Sudan. Tabasco sauce is so central to Southern eating that some of us carry tiny bottles of the stuff in our luggage for fear it won’t be available in foreign locales. And, not to cause alarm, but some scientists believe Tabasco is verifiably addictive—something to do with the flood of endorphins released as you ingest hot peppers. Once you’re accustomed to natural painkillers coursing through your brain, eating without that comforting burn just isn’t the same. See Avery Island; Hot sauce.

THE FORMULA FOR THIS “CONCRETE OF THE Lowcountry” dates back to the late 1500s: blend equal parts lime, sand, oyster shells, and water, and let dry until the mixture is just set but still pliable. Construction of building components made from tabby—walls, wedges, bricks, roofs, foundations, and floors, to name a few—peaked during the first half of the nineteenth century. By 1824, a range of domestic, industrial, civic, and religious structures using tabby were commonplace between Charleston, South Carolina, and St. Augustine, Florida, both along the coast and inland. In addition to being convenient, affordable to produce, and fireproof, tabby was extremely adaptable, allowing builders to get creative; in Woodbine, Georgia, workers poured a plantation house in the shape of a large anchor. One proponent of the material, the Georgia planter and statesman Thomas Spalding, recommended making it only between February and September to avoid winter freeze-thaw cycles and hurricane-prone autumn months, and to take advantage of high humidity, which shortened the setting time. Palmetto branches were used to protect batches of tabby from rainfall while it dried. For an up-close view of the sand-and-shell wonder, visit the Chapel of Ease on South Carolina’s St. Helena Island, Gamble Mansion in Ellenton, Florida, or the aptly named Tabby Manse, a circa 1786 spread near Beaufort, South Carolina.

THE SOUTH TAKES ITS FOOTBALL SERIOUSLY, and that dedication extends to the prelude known as the tailgate. Historians debate the first true instance of what is essentially a glorified, gussied-up cookout. Some point to the First Battle of Bull Run, in 1861, when spectators hitched up carriages, packed picnics, and traveled the thirty-odd miles southwest from Washington, D.C., to Manassas, Virginia, to witness—mind-boggling as it may seem—the first major encounter of the Civil War. Others cite the 1869 gridiron matchup between Rutgers and Princeton, which many consider the first intercollegiate football game. Wherever the tradition started, it is generally acknowledged that the South has elevated it, whether the spread of fried chicken, deviled eggs, burgers, brats, barbecue sandwiches, and, yes, booze takes place underneath the chandeliers of the tents dotting the Grove at Ole Miss; aboard the flotilla known as the Volunteer Army bobbing outside Neyland Stadium at the University of Tennessee; inside the tricked-out railroad car Cockabooses at the University of South Carolina; or on Jacksonville Landing for the infamous World’s Largest Outdoor Cocktail Party—the annual neutral-site Florida-Georgia grudge match. Of course, people tailgate before other events—NASCAR races, concerts, and the like. But pigskin pregaming sets the standard.

IF YOU’VE SPENT TIME IN THE MISSISSIPPI Delta, chances are you know about the “tamale trail.” As a rule, that unofficial connect-the-dots collection of gas stations, drive-throughs, and roadside vendors is first stumbled upon, then hunted down obsessively with maps and guidebooks. Unlike their heftier Mexican brethren, the Delta’s corn-husk-wrapped packages of tender masa and ground meat are often no bigger than a stubby finger. They arrive tied up in bundles of four or six and stained red with their spicy cooking juices. Locals eat them sandwiched between saltine crackers with a dab of ketchup, but in the early stages of obsession you’ll want to consume as many as possible in their plain state, singeing your fingers on the hot husks. A number of the region’s best-known restaurants offer their own versions, as well. Food historians suspect that Mexican migrant workers brought tamales to Mississippi in the early part of the last century, and they caught on as an easy-to-pack lunch for day laborers. Now they’re as much a part of Delta culture as the blues.

THINK OF THE MOST FEARSOME NFL RUNNING back you’ve ever seen. Remove his appendages, cover him in big platelike scales, color his sides and belly in brilliant silver and his back a dark greenish or bluish black, and give him a forked tail. Oh, and increase his strength fourfold. That is Megalops atlanticus, the tarpon, aka the silver king, one of the world’s premier game fish and one that American anglers eagerly seek worldwide—the current world record is a 286-pounder caught in 2003 off West Africa; the U.S. record, a 243-pounder caught in 1975 off Key West. It’s regularly caught by conventional and fly tackle off the coast of Florida, where tarpon often cruise shallow waters in schools. While tarpon are extremely bony and close to inedible, unless you’re really hungry, they are in all other respects a near-perfect game fish: big, powerful, spectacularly acrobatic, and challenging to hook and land. Upon being hooked, they often leap completely out of the water, at which time it’s advisable to “bow to the king”—that is, lower your rod tip so you have more slack line to absorb the impending shock. You must play the fish until it’s tired—this can take fifteen minutes or three hours—before bringing it alongside to remove the hook and release it. A “green” fish may pull a guide overboard or, worse, leap into the boat, where its thrashing has been known to break legs and railings. Biologists have been unable to detect in tarpon any sense of remorse.

(1949–)

SOME NATIVES OF CHARLESTON, SOUTH Carolina, might call John Martin Taylor, known fondly in the culinary world as Hoppin’ John, a “come ’yar,” because he was not born in the Lowcountry that he has written about so lovingly. Quite a few might not recognize his name at all—a pity, since Taylor’s books and advocacy of Charleston’s foodways heritage helped lay the groundwork for the resurgence of the city and its cuisine into the darlings of food lovers that they are today. Years before the likes of Sean Brock (of McCrady’s and Husk) and Mike Lata (FIG, The Ordinary) became Lowcountry food luminaries, Taylor was championing heirloom ingredients—Carolina Gold rice, benne seeds, sorghum—and all-but-forgotten recipes.

In 1986, after years working as a photographer and painter, Taylor (who grew up inland in Orangeburg) broke into the culinary field when he opened Hoppin’ John’s, a Charleston bookstore and mecca for chefs, overflowing with thousands of cookbook titles, one of the nation’s first to specialize in culinaria. His 1992 scholarly cookbook, Hoppin’ John’s Lowcountry Cooking, quickly became a classic, followed by The New Southern Cook, The Fearless Frying Cookbook, and Hoppin’ John’s Charleston, Beaufort, & Savannah: Dining at Home in the Lowcountry (most of them, sadly, now out of print, though you can ferret out copies online). Each took a deep dive into the region’s history and its distinctive culinary style. Although Taylor closed his store in 1999, he still markets heirloom stone-ground grits and cornmeal, both to consumers and to restaurants scattered around the country. Now in his sixties and residing in Savannah, he is both a local legend and a worthy doyen and guardian of the history and scholarship of Lowcountry cooking.

THE GAIT OF A TENNESSEE WALKING HORSE IS a thing of beauty. As the breed’s name implies, that beauty resides in its unique style of walking, with legs lifting higher and advancing faster than other breeds’ while still delivering a smooth, steady ride. A well-trained walker can do so in a basic “flatfoot walk” and a more pronounced “running walk,” in which the horse’s head bobs in sync with the gait. The breed was developed in the late 1800s as a cross between pacer breeds and Spanish mustangs, and given its characteristics became a popular show horse. Even the Lone Ranger and Roy Rogers rode walkers. Unfortunately, controversy also surrounds them. To exaggerate the walker’s high-legged gait even further in the arena, some trainers shoe the horses with weighted “performance” stacks that can cause pain. The United States Equestrian Federation prohibits that practice, which has led to acrimony among breeders and sanctioning organizations that stand on both sides of the debate. The breed’s biggest annual showcase, the Tennessee Walking Horse National Celebration in Shelbyville, Tennessee, allows the so-called action devices, attracting fans and animal-rights protesters alike.

TO BE CALLED BOURBON, WHISKEY MUST BE made from a mash of at least 51 percent corn; it must be aged in new charred oak barrels; and it can’t be bottled at less than 80 proof. But contrary to the near-religious conviction of many fans, it does not have to be produced in Kentucky to be called bourbon (though it must be produced in the United States). So why don’t bottles of Tennessee-made whiskey that meet all the requirements, namely, George Dickel and Jack Daniel’s, have the word bourbon anywhere on them? By tradition and choice, actually. Perhaps because they can’t match the output of Kentucky distilleries (from where 95 percent of the country’s bourbon flows), Tennessee distilleries have carved out their own brand identity. In fact, state law now restricts the term Tennessee whiskey to the stuff actually produced in the Volunteer State (take that, Kentucky!), and further requires (with rare exceptions) that it be made with a charcoal-filtering step known as the Lincoln County Process. Of course, many Kentucky bourbons are also charcoal filtered, further muddling any cross-border distinctions.

Tex-Mex IS A TERM THAT, WHEN USED BY Mexican nationals and much of this nation’s food elite, often translates to “Mexican food that’s been bastardized by a bunch of Texas rednecks.” The term was first applied to Americanized Mexican food, to distinguish it from authentic food of interior Mexico, after the 1972 publication of Diana Kennedy’s cookbook The Cuisines of Mexico. The English-born Mexican-food authority trashed the “so-called Mexican food” north of the border, with its messy combination platters and revolting appetizers such as “greasy chips and mouth-searing salsa.” Though originally intended as a pejorative, “Tex-Mex” now simply describes the bicultural regional cuisine of the Texas-Mexico border. Familiar Tex-Mex inventions include chili, nachos, Frito Pie, frozen margaritas, fajitas, breakfast tacos, and yellow cheese enchiladas.

The cuisine’s signature dish, chili con carne, was created by Spanish-speaking native peoples known as Tejanos in the late 1700s, during the era of the Spanish missions. They simmered minced meat and beef fat with ancho chiles for hours to make the tough longhorn beef raised on mission cattle ranches palatable. About a century later, from the 1860s into the 1930s, chili con carne grew in popularity thanks to the Chili Queens, flirtatious cooks who sold chili, enchiladas, and tamales in open-air food stalls in the squares of San Antonio, and became famous in the process. Writers such as O. Henry and Ambrose Bierce helped immortalize them, and newspaper travel correspondents penned romanticized coverage of them and the exotic Texas-Mexican culture they represented, once railroads enabled Midwestern tourists to visit Texas. The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893—attended by more than twenty-seven million people, a quarter of the U.S. population at the time—had a re-created San Antonio Chili Stand on its midway, serving legions of fairgoers the first “Mexican” food they’d ever tasted and sparking the spread of the dish far and wide. In 1895, what would become Wolf Brand chili debuted, initially sold by the bowl in Corsicana, Texas, by a former chuckwagon cook. By the end of the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904, chili parlors that sold chili con carne and tamales had opened in St. Louis and Carlinsville, Illinois. Grocery stores around the country soon began to sell Gebhardt’s and other bottled chili powders.

Around the turn of the century, a Chicagoan named Otis Farnsworth pioneered the Tex-Mex restaurant genre. While visiting San Antonio’s chili stands, he was shocked to see Anglos in fancy clothes lining up in the barrio to eat street food. So in 1899, Farnsworth built the Original Mexican Restaurant in San Antonio’s fashionable commercial district. The menu included the “Regular Supper,” which combined enchiladas, tamales, chili con carne, Spanish rice, and refried beans on a single plate; the “Deluxe Supper” added tacos and more. Cooks and waitstaff were Hispanic, but the customers were Anglos. Gentlemen were required to wear jackets.

Tex-Mex thrived in the early twentieth century, but the rise of the automobile led to a new kind of Americanized Mexican food. The Cal-Mex of Southern California featured cheap tacos in preformed taco shells sold in drive-in restaurants such as Taco Bell that began to dot the interstate highways. Burritos are another Cal-Mex standard that became a favorite across the country. Nowadays, few new Tex-Mex restaurants are opening; instead, hip taquerias like Torchy’s Tacos, Velvet Taco, and Tacos A Go Go carry on the bicultural food tradition.

Still, Tex-Mex has had a profound impact on American eating habits. Chili con carne endures as a classic one-pot meal, as well as a topping for hot dogs, burgers, and french fries. The Tex-Mex tradition of dipping tortilla chips in salsa, a spin on the potato chips and sour cream dips of 1960s suburbia, spawned a multibillion-dollar snack food category (Fritos, Doritos, Tostitos, et al.). And thanks in large part to San Antonio’s David Pace, inventor of Pace Picante Sauce, in the early 1990s salsa passed ketchup as America’s top-selling condiment.

EVEN IF YOUR ENTIRE EXPOSURE TO HORSE racing is watching the Kentucky Derby telecast once a year, you surely understand that all the excitement, all the mint juleps, all the hats, spring from the simple question of which Thoroughbred horse is the fastest. Thoroughbreds, though also prominent in show jumping, dressage, and polo, are synonymous with racing. The breed—tall, lean, muscled—came to the American colonies from England and matched our national character well with its hot-blooded spirit and speed. Today the horses are the center of a $34 billion industry (at Keeneland, the prestigious Thoroughbred auction house in Kentucky, promising yearlings regularly fetch north of a million dollars) and a worldwide culture that operates with its own language, customs, and scandals. A very precious few of these horses earn quirky names such as Seattle Slew and American Pharoah and win the Triple Crown. Most don’t, of course. But even an anonymous Thoroughbred racing nothing but its own shadow across a morning pasture is a sight as thrilling as any high-stakes photo finish. See Keeneland; Kentucky Derby.

GEOLOGISTS, ESPECIALLY NON-SOUTHERN ONES, define tidewater as a region where freshwater meets salt, and rivers rise and fall with the tides. There are tidewaters up and down the East Coast. But there’s only one Tidewater with a capital T, and it belongs to Virginia, much as the Lowcountry belongs to South Carolina and Georgia. Four great rivers—the Potomac, Rappahannock, York, and James—slice through Virginia on their way from the Appalachians to the Atlantic. They spill into Chesapeake Bay, the largest estuary in the Lower 48. Tidewater Virginia, called “a blend of romance and fact” in a 1929 book by the same name, starts east of the rocky fall line, where these and other rivers meet the coastal plain and curl back on themselves in lazy oxbows.

For many historians, Tidewater Virginia is the cradle of America. Jamestown, the first permanent settlement among the original thirteen British colonies, is there, as are the former colonial capital Williamsburg and Yorktown, site of George Washington’s decisive victory over the British in 1781. Five U.S. presidents were born in the Tidewater, among them Washington and James Madison, father of the Constitution.

In A Tidewater Morning, the writer William Styron, a native of Newport News, wrote: “I came to absorb the history of the Virginia Tidewater—that primordial American demesne where the land was sucked dry by tobacco, laid waste and destroyed a whole century before golden California became an idea, much less a hope or a westward dream.” He recalled the “scores of shrunken, abandoned ‘plantations’ scattered for a hundred miles across the tidelands between the Potomac and the James.” And he reflected on the changes wrought during the 1930s in the lead-up to World War II. “[The Tidewater] was not the drowsy old Virginia of legend but part of a busy New South, where heavy industry and the presence of the military had begun to encroach on a pastoral way of life.”

Since then, Newport News, Norfolk, Portsmouth, Chesapeake, and Virginia Beach have fused into a Tidewater megalopolis. Nevertheless, sportsmen, boaters, and weekend warriors from Richmond and other cities cherish the region, sometimes known simply as “the Rivah.” They flock to homes and marinas nestled among the filigree of spits, sloughs, creeks, and bluffs lining the great estuary.

A NIGHTCLUB IN NEW ORLEANS’ UPTOWN neighborhood, Tipitina’s is one of the chief stops on a musical pilgrimage to the Crescent City. While it does not have the ancient lineage of other clubs that served as nurseries of American jazz and rock (many since shuttered), for four decades Tipitina’s has been a greenhouse extending the longevity of traditional New Orleans music.

The club was founded in 1977 by a group of music fans dismayed to discover the legendary blues singer and pianist Professor Longhair (also known as “Fess,” born Henry Roeland Byrd), then nearly sixty years old, was playing in obscurity at sketchy venues. They established a neighborhood club on Napoleon Avenue, naming it after one of his best-known songs. Fess often played at the club until his death, in 1980. The club underwent a major remodeling in 1984, when the upstairs apartments of the 1912 building were converted into a mezzanine overlooking the stage and club floor. Tipitina’s Foundation, the club’s nonprofit arm, has long supported local musicians both in deed and financially, and it was especially active in replacing instruments lost by school bands during Hurricane Katrina. The club’s logo includes, somewhat inscrutably, a partially peeled banana. This is an artifact of Tipitina’s original incarnation as a juice bar; bananas are no longer available there.

IT IS REMARKABLE THAT GEORGE W. BUSH awarded Harper Lee the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2007 for her contributions to literature despite the fact that she had published only one book. Published in 1960 (and winner of a Pulitzer Prize the following year), To Kill a Mockingbird is the still-powerful, much-beloved story of a lawyer who defends a black man accused of raping a white woman in Depression-era Alabama, of his children and a mysterious neighbor, and of a small town infected with calcified racism. It’s a vision of Lee’s South both lovely and terrible. A little like an Uncle Tom’s Cabin for the twentieth century, Mockingbird quickly burrowed into the American consciousness as a kind of definitive portrait of race and region in a particular moment in time, spawning a popular 1962 film adaptation starring Gregory Peck. Lee insisted that the novel was not autobiographical, despite the fact that she, like her heroine Scout Finch, grew up during the Depression in small-town Alabama, where her father, also a lawyer, had defended two black men in a murder trial. See Lee, Harper.

EVERYBODY MAKES TOMATO PIE A LITTLE BIT differently, but the basic ingredients remain pretty much the same: garden-fresh summer tomatoes, cheese, and plenty of mayonnaise, all baked in a pastry crust, something like a Southern answer to a deep-dish pizza. Although the use of mayonnaise most likely dates the savory pie to the mid-twentieth century, today it’s as entrenched a seasonal tradition as holiday ham. Though occasionally fancied up with chopped herbs or goat cheese, tomato pie generally hews to the same boy-is-it-hot simplicity as its close cousin, the tomato-and-mayonnaise sandwich on white bread. Here, too, every ingredient matters. Don’t even bother trying to make a pie out of mealy supermarket ’maters.

(1937–1969)

IN 1976, THE CELEBRATED NOVELIST WALKER Percy received a phone call from a woman he did not know. What she suggested over the line was, as Percy put it, “preposterous.” Her son, John Kennedy Toole, who had taken his own life seven years earlier, had written a very long novel in the 1960s and never gotten it published, but now she wanted Percy to read it. When Percy asked why, Toole’s mother said, “Because it is a great novel.” Percy obligingly and politely skimmed the first few pages, keeping his eye out for any reason to stop. He never found one. What he found instead was Ignatius Reilly—perhaps the finest comedic personage ever to appear in American letters—tearing across New Orleans in a succession of lunatic escapades. Within this Falstaffian farce, entitled A Confederacy of Dunces, Toole somehow managed to create a story at once hilarious, sad, and profound. It is said that Toole’s suicide was prompted in part by depression brought on by the novel’s multiple rejections; with Percy’s help, though, the book was finally published in 1980. The next year Toole posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

(1928–)

IN A FORMER WELDING SHOP ON THE BANK OF Louisiana’s Lafourche Bayou, Alzina Toups has been cooking and serving transcendent Cajun food for forty years: gumbo, lima beans, black-eyed pea jambalaya, and countless shrimp and crabmeat dishes spiked with garden herbs. Toups lives and works in Galliano, a short drive from the Gulf of Mexico, where she was born to a Cajun fisherman and a Portuguese mother. She learned to debone a fish on her father’s boat and inherited her mother’s appreciation for the simple but deep flavors of Cajun cuisine and the region’s bountiful produce and seafood. Her talent is legendary among townsfolk and the local Catholic clergy, who know her from Mass. And, increasingly, she’s appreciated around the world. She has fed New Yorkers and Frenchmen and a party of twenty German chefs at the unadorned table in her kitchen. Everybody eats family-style beneath an image of the Virgin Mary. It may sound humble, but the food certainly isn’t, and that’s why Alzina’s is harder to get into than most Michelin-starred restaurants. She only takes reservations, and she’s usually booked four months out.

(1966–)

“IN THE PORTRAIT OF JEFFERSON THAT HANGS at Monticello, he is rendered two-toned” is how Natasha Trethewey begins “Enlightenment,” one of her many Southern-steeped poems that probe the region’s dualities: celebrated and condemned; spiritual and sensual; black and white. Born in 1966 to a black mother and a white father in Gulfport, Mississippi, Trethewey split her childhood between their homes after their divorce, an arrangement that introduced her to the intricacies of skin tone and passing. She was a nineteen-year-old cheerleader at the University of Georgia when her ex-stepfather murdered her mother; Trethewey first started writing poems as a way to manage her grief. In 2000, she published her first book, Domestic Work, a collection of poems about black Southerners’ labor. The poet Rita Dove praised Trethewey for pressing beyond descriptive scenes to wrestle with fears and desire, awarding Trethewey the first of many prestigious prizes she would claim. She received the Pulitzer Prize in 2007 for a set of ten sonnets, elegies, and autobiographical poems devoted to an African American regiment that guarded a Confederate prison. She was named the poet laureate of Mississippi in 2012 and the poet laureate of the United States in 2012 and 2014.

IT’S REALLY JUST AN OLD, BATTERED MARTIN N-20 classical acoustic, nylon-stringed, with a Prismatone stereo electric pickup salvaged from a busted Baldwin guitar. But put the weathered instrument in the hands of its owner and it magically becomes Trigger, storied accompanist to one Willie Hugh Nelson, Texas musician. There’s a second oblong hole worn above the bridge and below the circular sound hole, carved by millions of hand strokes, picked single notes, and chord strums over the course of tens of thousands of songs. The faded scribbles of Leon Russell, Kris Kristofferson, Ray Price, Merle Haggard, and scores of other close personal music friends adorn the Brazilian rosewood.

The look may be distinctive, but the tone is wholly unique. Two notes picked on those six strings is all it takes to know it’s Willie playing. The fluid strings allow him to channel one of his greatest inspirations, the Romany guitarist Django Reinhardt, and bend and sustain notes in a manner steel strings cannot replicate.

It has been like that since 1969, when Shot Jackson installed the pickup, giving Willie the sound he was looking for to complement his behind-the-beat jazz-styled vocals. Starting with My Own Peculiar Way, the RCA album released in 1969 toward the end of Nelson’s Nashville residency, up to the here and now, Trigger has been a constant—sonically, physically, and spiritually. The guitar is stewarded, shepherded, and babied by the longtime instrument technician Tunin’ Tom Hawkins, who fiercely protects his charge and skillfully telegraphs “Don’t even think about it” with his stage scowl. Tunin’ Tom knows: Without Trigger, Willie would be naked. With Trigger, anything can happen. See Nelson, Willie.

THROUGH IRON-POT ALCHEMY, ENSLAVED COOKS in antebellum times transformed humble pigs’ feet—aka trotters—into dishes that persist today. Rich in gelatinous cartilage, they add rib-sticking heft to pots of greens and peas. Braised and smoked, they stand alone at soul-food joints across the turnip-green and neck-bone diaspora. Pickled, they’re a gas-station standby. See Pigs’ feet.

(c. 1820–1913)

HARRIET TUBMAN DIDN’T CARE IF YOU WERE frightened—she was going to get your ass free. Known to pull a loaded revolver on timid slaves in an effort to urge them along the Underground Railroad, Tubman was one of the Railroad’s most effective conductors, leading more than three hundred slaves to freedom. Along the way she earned the nicknames Moses and General Tubman. A fierce and righteous abolitionist who had escaped slavery herself in 1849, Tubman worked for Union forces in South Carolina during the Civil War, serving as, among other things, a spy. Using knowledge gathered on her reconnaissance missions, she guided Union troops on the Combahee River Raid, which led to the emancipation of seven hundred South Carolina slaves. In doing so, Tubman became the first woman to lead an armed mission in the Civil War. In April 2016, 103 years after her death, it was announced that Tubman would achieve another first for an American woman: she would take the place of Andrew Jackson on the twenty-dollar bill, becoming the first woman featured on American paper currency.

WE’RE TALKING ABOUT THE EDIBLE VARIETY, not the Van Morrison ballad (although both are classics). Sometimes called the champagne of honeys, tupelo honey comes from a small area of northwestern Florida and southern Georgia, where bees tap ogeechee trees growing along the Apalachicola, Chipola, Ochlocknee, and Choctahatchee Rivers. Some have described its taste as buttery and mildly floral, without the cloying sweetness of other honeys. And because it has low levels of glucose, it’s the only honey that some diabetics can safely eat. Bees produce the honey in springtime—typically May—when the starburst blossoms are dripping nectar. Beekeepers then harvest it from hives they’ve placed along the riverbanks on floats (often they need boats to access them in swampy precincts). If that sounds like a lot of work, it is. But you’ll understand what the buzz is about when you drizzle some over a warm hunk of cornbread.

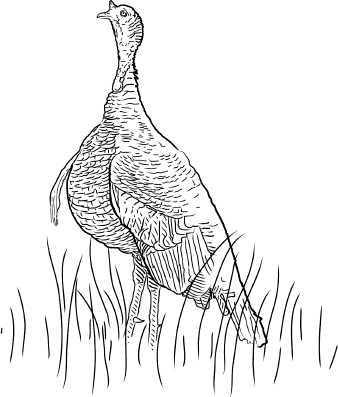

THE WAY TO HUNT TURKEYS IS TO RISE about the time you would otherwise be going to bed, and dress yourself in camouflage from head to toe, including hat, gloves, face mask, and snake boots. Some guys wear sunglasses with camo frames and even lenses (violating all sorts of laws of optics and nature). Arm yourself with a shotgun that shoots watermelon-sized patterns at sixty yards. This can only be achieved by using a special “turkey choke,” such as the BlackOut, UnderTaker, or Jelly Head. Ideally, you will have roosted birds the night before. This means you’ll have scouted the area and actually seen the tree into which the birds flew to spend the night. Ideally, you will also have identified where they’re most likely to head—usually an open space like a meadow or a field—and can set up to intercept them there. Since you failed to do either of these, simply slip through the woods until you hear gobbling or stumble across an area that “feels” like it might attract turkeys. Choose a broad-trunked tree and take a seat at its base. The tree breaks up your outline to the sharp-eyed wild turkey and keeps you from falling over backward when you doze off. Turkey hunting doesn’t have to involve long periods of inactivity, but it tends to.

Sit there for hours or until all feeling has left your lower body, whichever takes longer. If you wish, select from the wide variety of turkey calls—box calls, friction calls, diaphragms originally made of condom latex, gobble tubes, etc.—and make any of the dozen or so of the bird’s known vocalizations. I’ve never found this to make the slightest difference, but it passes the time. It’s also a good way to attract the attention of other hunters, who may think you’re a real turkey and come try to shoot you. Some turkey hunters contend that this increased danger keeps them alert. (Incidentally, if you do see another turkey hunter, shout to him but do not move. Moving is a good way to get mistaken for a turkey.) Around noon, attempt to stand up and restore blood flow to your lower extremities. Make your way back to camp. When your friends ask how you did, say, “Well, I was all covered up in ’em. I mean, thick as ticks on a dog’s back. Gobblers in front, behind, left, and right. They had me pinned down, but they were all henned up and wouldn’t come in.” Your friends will nod, express sympathy, and say they’ve had the exact same experience. This is complete bullshit.

I’ve actually killed quite a few turkeys, but always while being guided by someone who knew the area, understood how turkeys will most likely react in a given situation, and knew how to call to them and get them to approach. Basically, all I did in any successful turkey hunt I’ve taken part in was pull the trigger when told to and then pose heroically with the bird. I call this “baby-in-the-car-seat hunting,” for the approximate skill level it required of me.

I shot my first turkey from a pop-up blind, sitting on a small folding chair with my gun barrel sticking out of one of its shooting ports. I had to lean slightly uphill, I remember, because the blind wasn’t pitched on flat ground. About an hour after sunup, my guide successfully called in two toms. “Shoot the one on the left,” he said. “Aim halfway up his neck.” I did, but in the excitement of the moment, I’d forgotten about the recoil of a three-inch 12-gauge turkey load. Before the pellets had left my gun barrel, I had left the chair and was flying backward inside the blind, fully horizontal, like a camo flying carpet. And thinking, “Wow! I just killed my first turkey!”

(1938–)

IN A REGION FULL OF COLORFUL CHARACTERS, consider the self-made billionaire Robert Edward Turner III a double rainbow. The near-bottomless résumé of the man who personifies “crazy like a fox” reads like Renaissance Man Mad Libs: America’s Cup winner; former owner of the Atlanta Braves and the Atlanta Hawks; bombastic genius behind the first cable “superstation”; founder of the first twenty-four-hour news network, CNN, as well as TBS, TNT, Turner Classic Movies, and Cartoon Network; creator of the Goodwill Games; erstwhile owner of World Championship Wrestling; ex-husband of three women, including Jane Fonda; owner of the world’s largest private herd of bison, an animal he helped bring back from the brink of extinction (its meat now served at more than forty Ted’s Montana Grills around the country); champion of environmental causes, from clean energy to sustainable land management; second-largest landowner in America, with more than two million acres; benefactor of the United Nations Foundation he helped form to the tune of $1 billion; cohead of the Nuclear Threat Initiative, which encourages global disarmament; consummate outdoors-man, fisherman, hunter, horseman, you name it. Although the freewheeling media mogul was born in Ohio, he made his fortune in Atlanta, a place he helped shape into the city you see today. In the years following the disastrous merger of his Time Warner with AOL in 2000—a deal that ultimately cost him billions—Turner may have slowed a little. But don’t feel too sorry for “Captain Outrageous”: he still has twenty-eight homes and, at last count, four girlfriends.

(1835–1910)

MARK TWAIN DIDN’T HAVE DEEP SOUTHERN roots. His parents were from Virginia and Kentucky, which may be Southern enough for most people, but not for anybody who comes from farther down. He was born and grew up in the border state of Missouri. As for the territory between there and New Orleans, he made its acquaintance mostly in passing, from Mississippi riverboats. He lived and worked in Pennsylvania, Ohio, California, Nevada, Connecticut, New York, and Europe.

So why do we call him a Southern writer?

He cherished Southern cooking: “Perhaps no bread in the world is quite as good as Southern cornbread, and perhaps no bread in the world is quite so bad as the Northern imitation of it.”

He cherished Southern talk. “A Southerner talks music,” he wrote, but his appreciation of that music was not limited to the melodious. Several regional dialects, black and white, smooth and scabrous, went into the voice of Huckleberry Finn, which (thanks to Twain’s easy command of formal syntax and literary language as well) became the template of modern American narration.

He turned his two weeks or so with a jackleg attachment to the Confederate army, which culminated in the killing of a hapless lad like him, into a darkly comic tour de force. Most important, he faced up to something he had not realized the evil of during his all-American boyhood. He had to account for growing up surrounded by slavery (and related “windy humbuggeries”), and therein lies the soul of his work.

Twain was certainly good at what most people may think of when it comes to Southern humor: hyperbole, flamboyant characters, animal noises. But he also had a great touch for a quieter, more elliptical sort of joke, which adds a Zen-like spin to something that would appear to be stupid. When he was born in the town of Florida, Missouri, he tells us in his Autobiography, the town “contained a hundred people and I increased the population by one per cent. It is more than the best man in history ever did for any other town.” This, I submit, is in the same crisp suprascientific vein as the joke I have called the quintessential Southern one: Old boy is asked whether he believes in infant baptism. “Believe in it?” he says. “Hell, I’ve seen it done.”

Here’s another. A house comes floating down the Mississippi after a flood. Huck and Jim board it, to see what they can scavenge. Huck gives us a long list of conceivably useful odds and ends, of which this is the last item: “Jim he found . . . a wooden leg. The straps was broke off of it, but, barring that, it was a good enough leg, though it was too long for me and not long enough for Jim, and we couldn’t find the other one, though we hunted all around.”

If there were a Museum of Classic Southern Humor, it would feature a large monument—an obelisk, say—to that other leg. But the joke runs deeper. The flood-borne house also contains a pile of stuff that Jim checks out. He sees that it’s a dead body. Don’t look at the face, he tells Huck, “it’s too gashly.” So they go about gathering a fine miscellany of stuff that might come in handy—“a tolerable good currycomb,” “a ratty old fiddle-bow,” and so on. So much for the dead man, for now. But that body, we will come to find out, is all that’s left of what really could have been valuable to Huck, if this one had not, in life, been such a sorry excuse: his father.

See Faulkner, see Flannery O’Connor, see Cormac McCarthy: it is truly Deep Southern for humor to border on the horrible.

ON FEBRUARY 5, 1958, HIGH OVER SOUTH Carolina’s Daufuskie Island, an Air Force B-47 was in trouble. The bomber, under the command of Colonel Howard Richardson, was heading back to Homestead Air Force Base in Florida, from a simulated bombing of Reston, Virginia. It was carrying a hydrogen bomb.

Colonel Richardson thought the exercise was over, when an F-86 fighter clipped his aircraft in midair, shearing away its number-six engine. The F-86 spun out of control, and its pilot ejected. The B-47 plummeted more than three miles before Richardson regained control. The crew requested permission to jettison the bomb, a precaution in case of a crash or an emergency landing. Permission was granted, and the bomb was dropped while the plane limped along at 200 knots and 7,200 feet of altitude, barely airborne. The crew noted no explosion when the bomb struck the sea. They managed to land the B-47 safely at an airfield outside Savannah.

The next day, February 6, a recovery effort began for what came to be known as the Tybee Bomb. The Mark 15 bomb weighed 7,600 pounds, and contained 400 pounds of high explosive and enriched uranium. Some sources describe it as a fully functional nuclear weapon; others claim it’s disabled. If a nuclear detonation ever occurred, it would cause a fireball with a radius of 1.2 miles, and severe structural damage and third-degree burns for ten times that distance.

On April 16, 1958, the military announced that search efforts had been unsuccessful, and the bomb was presumed lost.