IF YOU THINK YOU’RE PREVENTING WASPS from nesting on your porch by painting the ceiling blue to mimic the sky—a common Southern practice, especially in Georgia and the Carolinas—you might want to stock up on calamine lotion. Perhaps prior to the Civil War when milk paints, often containing lye (a known insect repellent), were used, that theory might have held a small kernel of truth. But even that’s a stretch. The tradition actually originated with the Gullah Geechee people of the South Carolina and Georgia Sea Islands, who called the color “haint blue.” They believed the blue-green hue protected a home from troubled spirits (or “haints”)—and often used it to paint doors and window trim as well as porch ceilings. The preferred Gullah shade is typically a bright Caribbean blue (almost turquoise), but you can spot dozens of variations ranging from robin’s egg to ice blue.

A TERM THAT CAN REFER EITHER TO A BALANCED blend of sweet and unsweet tea or to the popular mixture of sweet tea and lemonade. See Palmer, Arnold.

(1873–1958)

WAY BEFORE THE MUSCLE SHOALS SOUND was a thing, a fellow named W. C. Handy had an even greater impact on popular music. Born in Florence, Alabama, in 1873, Handy is often dubbed the “father of the blues” for his role in bringing a regional style (Delta blues) into the national consciousness. Handy traveled all over the South, playing with local groups, before settling in Memphis and then New York City. He composed a number of songs that became hits, including “Memphis Blues” and “St. Louis Blues,” with Bessie Smith’s version of the latter becoming one of the seminal recordings of the 1920s. Handy was also a musicologist, publishing blues anthologies and sheet music and diligently documenting the rise of the blues as an art form.

(1942–2010)

PATRON SAINT OF POSTMODERN SOUTHERN literature, Mississippi’s Barry Hannah was a comic prose stylist, a wild man, a motorcycle rider, a trumpet player, a drunk hilarious jerk, and, in the end, a sober literary legend. Perhaps best known for his short story collection Airships, Hannah was the writer in residence at the University of Mississippi for decades, and, while he may not have achieved the sales numbers of some of his contemporaries, he is revered by generations of his peers as the finest and most lovable of them all. Of his seemingly effortless and unmatchable talent, the late author Jim Harrison once said that Hannah was “brilliantly drunk with words and could at gunpoint write the life story of a telephone pole.” See Brown, Larry; Oxford, Mississippi.

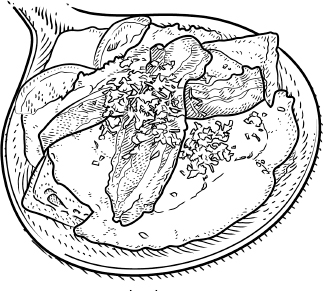

EATERS WHO ARE JUST STARTING TO APPRECIATE the diversity of Southern barbecue sometimes flinch at the notion of mustard sauce, one of four sauces traditionally associated with South Carolina. But if you really want to blow the minds of barbecue beginners who think the gamut of smoked meat sides runs only from hush puppies to mac and cheese, tell them about hash. Like burgoo in Kentucky or Georgia’s Brunswick stew, South Carolina hash is a one-kettle wonder dreamed up to use parts of the pig that no one could easily or attractively serve any other way. As the hash historian Robert Moss has put it, “You shouldn’t inquire too closely as to what goes in the hash pot.” But it’s safe to assume that onions, potatoes, and spices are simmering down with the offal; just as with barbecue sauce, ketchup or mustard sometimes finds its way into the mix too, meaning the hash served at a church in the Pee Dee region may taste slightly different from the hash spooned out at a volunteer fire department fund-raiser in the Midlands. The end product—too thick to be called gravy, too thin to qualify as a stew—is always paired with rice, a vestige of its plantation origins.

WHEN THE REVEREND HENRY WARD BEECHER, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s brother, came to Nashville to speak in 1879, Charles and Herbert Hatch printed the handbills. The brothers laid out carved woodblocks, inked them by hand, and ran them through a letterpress. It was their very first job. Almost 140 years later, Hatch Show Print still makes posters exactly the same way. In the meantime, it has become a cornerstone of Southern culture by creating thousands of pieces of graphic perfection, promoting more than a century of Nashville performances. Originally naming their company CR and HH Hatch, the brothers changed the name to Hatch Show Print to prevent people from mistakenly thinking they ran a hatchery. By the time Charles’s son Will T. Hatch took over in the 1920s, Nashville had become a show town, and business was flourishing. Hatch Show Print has cranked out thousands of hand-printed posters for circuses, vaudeville acts, sporting events, and, of course, the golden age of country music. Now part of the Country Music Hall of Fame, Hatch Show Print designs some six hundred new posters a year, its work coveted by performers, collectors, and graphic designers the world over.

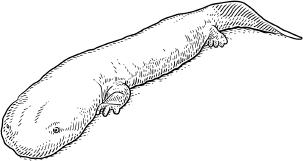

THE FIRST THING YOU NEED TO KNOW about the hellbender is that it exists. It’s not some sitting-by-the-campfire creation your troubled scoutmaster invented, he whose second-greatest pleasure came from supplying bad dreams to young minds. The hellbender is out there. You probably won’t ever see one, but if you do, it will be a terrifying confrontation and you will have every reason to believe you have stumbled through a rift in time and find yourself feeling a bit Jurassic.

The hellbender is a giant salamander. It’s been around for about sixty-five million years, and there’s a reason for that: It’s the only thing that’s both giant and a salamander, traits that don’t often go together. It’s the largest amphibian in North America, growing up to three feet long and sometimes weighing six pounds. With beady eyes, a wide-gaping biting mouth, and wrinkly skin, covered in slime, it has been called the ugliest animal on earth. It looks like a Komodo dragon run over by a car. On the other hand, it has a great sense of smell and photosensitive skin, so it knows when the entire length of it is concealed beneath a rock, because there’s nothing more embarrassing than to think you’re concealed beneath a rock and to not be. Hellbenders can live for fifty years and love nothing better than crawfish for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

The hellbender lives a long, solitary life, and in fact does spend most of its time under rocks. The only time a male and a female get together is to breed, and even that takes place externally: the boy hellbender gets the girl hellbender under his rock, and she lays her eggs and leaves, whereupon the boy hellbender disperses his sperm above them, hopes for the best, and guards the eggs until they hatch. You never want to mess with a hellbender when he’s guarding his eggs. There’s no telling what he might do.

Then there’s the name. Hellbender. To be called a hellbender, no matter what kind of animal you are, is a lot to live up to; for a salamander, no matter how large, it would appear impossible, which may explain why the hellbender salamander lives under a rock. The name suggests a power greater than Satan’s, as if the salamander were saying, “I ain’t scared of hell. Hell, I can bend hell. That’s why they call me—”

Or maybe it’s not that but something else. Maybe it’s called that because it’s so ugly that it could only have come from hell and is bent on returning there. But it’s been called all kinds of other things, too, none of them much more affectionate: snot otter, mud-devil, devil dog, grampus.

As a boy I spent a good part of my summers in creeks. This was in Alabama. I was a salamander and crawfish hunter, and I was pretty good at it, adept even, capable of lifting rocks from soft sediment without disturbing the clarity of the water. Hellbenders live under big flat rocks, the kind I would carefully pry my little fingers beneath and lift with the studied care of a safecracker. I never saw one. Alabama is about as far south as they get, though, and they are very sensitive to changes in water quality, to mining, and to sedimentation, so they’re becoming endangered. Some people keep them as pets. I don’t suggest keeping a slippery flat-headed creature from hell in your bedroom aquarium. That’s not a good thing, not for the hellbender and certainly not for you. I’d worry about after nightfall, the two of you alone, and you learning, finally and for certain, where the slimy little rascal gets its name.

(1953–)

INEXPLICABLY, IT TOOK FOREIGNERS (The London Observer) to point out that Florida-born Carl Hiaasen is “America’s finest satirical novelist.” Born in 1953 and raised in Plantation, Florida, by twenty-three, Hiaasen was a reporter for the Miami Herald. He still writes a regular column for the paper, which, according to his website, “at one time or another has pissed off just about everybody in South Florida, including his own bosses.” He has also produced fifteen novels (virtually all best sellers), including Skinny Dip, Bad Monkey, Lucky You, and Native Tongue, five children’s books, and five nonfiction books. Like that of all satirists, his work is fueled by righteous anger. Unlike most, his home state provides him with endless material. “This is an economy based on growth for the sake of growth . . . we don’t produce anything except oranges and handguns.” He acknowledges that it’s difficult even in fiction to do justice to the world around him. “There has been more than one occasion,” he told 60 Minutes in 2005, “where I wrote what I thought was the sickest possible scenario . . . only to have real life come along and trump me shortly afterward.” His novels do offer the satisfaction—as so seldom happens in real life—of bad people getting what they deserve. One villain was speared on the bill of a stuffed marlin. A few have been eaten by alligators. One was “romanced” to death by an amorous sea mammal, Dicky the Friendly Dolphin (based on an actual event, although that one only injured the man involved, but one doubts he has swum with dolphins since). Until Judgment Day, Hiaasen may be as close to justice as one can hope for.

ON FEBRURY 17, 1864, A STEAMBOAT ENGINEER turned Confederate lieutenant named George E. Dixon steered the Civil War submarine H. L. Hunley toward its final mission. His target: the USS Housatonic, a 205-foot Union sloop that held the northernmost point in the blockade of Charleston, South Carolina. When the Hunley first launched in 1863, she was considered by many to be a strange contraption (as submarines mostly were in those days); her slender forty-foot hull and protruding latches made for an unusual sight. By the end of her first year, she would earn the nickname “Little Devil” after sinking and killing thirteen crewmen during two test runs. Dixon, however, wasn’t thinking of the past on that fateful night; his mission was clear. With a single torpedo in its arsenal, the Hunley attacked, becoming the first sub in history to defeat an enemy ship (a feat that went unmatched until World War I) before sinking with her eight-man crew into the Atlantic and immortality. A protracted recovery effort—in which both the showman P. T. Barnum and, later, the author Clive Cussler were invested—lasted 131 years before the vessel was finally discovered and raised in 1995. Today it is permanently docked and open for tours in North Charleston—proving that even a ghost ship can remain undercover for only so long.

CONTRARY TO RUMOR AND SPECULATION, it’s doubtful the hoecake’s name owes anything to farming implements. Hoe is an antiquated term for griddle. Adapted from indigenous recipes, the proto-cornbread flapjack serves as a vehicle for any number of toppings. George Washington ate his with butter and honey; in twenty-first-century Nashville, Pat Martin of Martin’s Bar-B-Que Joint heaps them with pulled pork and slaw to make his Redneck Tacos. In Lumberton, North Carolina, members of the Lumbee Tribe eat hoecake-and-collard sandwiches at the annual Robeson County Fair. A versatile role player in Southern foodways, the hoecake has long been the anchor for a workingman’s lunch.

Holler IS THE VERNACULAR FORM OF hollow, a narrow, steep-sided valley. Hollers are often reachable only by single-lane roads that cling to slopes or trace winding streambeds. These isolated coves are significant for the way they shaped the culture and language of a broad swath of the South, the region known as Appalachia. Formed eons ago by continental upheaval that folded the land into accordion-like ridges and valleys, hollers have, for better or worse, served as redoubts against the onslaught of urbanization and cultural homogeneity.

Providing plenty of water, timber, and arable land, hollers have long bred self-sufficiency. When other parts of the antebellum South were given over to vast plantations producing commodity crops such as cotton, Appalachian hollers remained home to fiercely independent economic generalists, who hunted, trapped, gathered, farmed, and kept hogs and milk cows. The rise of industrialization and urbanization that followed the Civil War reached the hollers only slowly. Outside encroachment finally came during the twentieth century. Extractive industries such as timber and mining hit Appalachia hard, driving many inhabitants to pick up and move west. But the hollers’ culture of kinship, feuds, folktales, and hardscrabble self-reliance—not to mention one of the country’s most distinctive dialects—lives on.

BORN IN THE BAWDY BARS OF THE SOUTH, honky-tonk music pairs the raw, ragged sounds of guitar, fiddle, steel guitar, and string bass with lyrics about broken hearts and drinking. Ernest Tubb jump-started the genre in the 1940s, and Lefty Frizzell and Hank Williams brought it to ubiquity in the 1950s, setting the standard for “real” country music. The term can also refer to a bar in which such music is played, as in “I’m going to drink my way through all the honky-tonks on Lower Broadway.” And it’s sometimes turned into a verb, as in “My head hurts real bad from honky-tonkin’ all night.”

AFTER EMANCIPATION, COTTON GROWERS IN the Mississippi Delta were desperate for cheap labor, so they recruited men from Sze Yap, an area in South China. The Chinese workers weren’t pleased with the state’s treatment of nonwhites or satisfied with the pay. But they realized there was money to be made in grocery stores; the first Chinese-owned grocery in Mississippi likely opened in the 1870s. In the early 1900s, Hong Lee followed his countrymen to Mississippi from Canton, opening a general store in the Delta town of Louise. His son, Hoover, inherited the store, and in the 1980s started selling his signature blend of soy sauce, garlic, and sugar. (Before the sauce became available online, Lee advised curious eaters elsewhere to imitate the flavor by combining hoisin sauce with onion powder, minced garlic, and chopped cilantro.) Delta residents, who got to know Hoover Sauce in the 1970s when Lee first served it at community events, say the salty-sweet condiment perfectly complements steaks, wings, venison sausage, and just about anything else that might end up on your plate.

ON NEW YEAR’S DAY IN THE SOUTH, RESOLUTIONS traditionally come with a generous helping of hoppin’ John, a pork-flavored stew of rice and black-eyed peas, which are thought to bring good luck. The recipe itself varies from cook to cook. The James Beard Award–winning chef Sean Brock, who routinely obsesses over the history of Southern ingredients and flavors, believes Lowcountry cooks originally prepared hoppin’ John with Sea Island red peas and Carolina Gold rice. Robert Stehling, the chef and owner of Hominy Grill in Charleston, South Carolina, adds a secret ingredient, Benton’s hickory-smoked bacon. No matter how you tweak it, serve the dish with a heap of slow-cooked greens (which represent money in New Year’s tradition) for a belly that feels—on January 1 or any other day—very fortunate, indeed.

NO OFFENSE TO FRED SCHMIDT, THE CHEF AT Louisville’s Brown Hotel who back in 1926 came up with the Hot Brown as a late-night snack, but the first people to sample his open-face sandwich most likely didn’t realize they were beholding a local legend in the making. After all, Hot Brown is close kin to Welsh rarebit, a chafing-dish classic that became a party fixture after John Jacob Astor’s wife in 1914 treated guests to melted cheese on toast, iced eggs, and hot coffee in between dances. Smart hostesses across the South followed her lead, but Schmidt adjusted the basic recipe so it would counterbalance high-octane hooch even more forcefully, piling sliced turkey, bacon, Mornay sauce, and broiled tomatoes atop thick-cut bread. Imaginative Kentuckians have since tinkered with the basics, incorporating avocados, mushrooms, and American cheese, but the Brown Hotel hasn’t wavered in its allegiance to tradition. The hotel serves about eight hundred Hot Browns a week (always with a knife and fork, since the sandwich is meant to be a molten mess)—and during Derby Week, closer to four hundred a day.

MOST PEOPLE CAN’T IMAGINE WHY ANYONE would ingest anything that makes them go NYAUGGHHH NYAUGGHHH and spit spit spit and WHOOO WHOOO as the tears roll down and their faces go numb. And yet the hot-sauce industry keeps turning out products with names like (and these are imaginably actual names) Aunt Mamie’s Burn Your Guts Out You Crazy Doomed Bastard You or Sold for Treatment of Parasites Only.

There are metrics involved. Something known as the Scoville scale ranks hot sauces according to how many units of sugar water you would have to add to a drop of a given hot sauce in order to dilute it enough to take the hot out of it. The hottest possible sauce is sixteen million Scoville units, which is achievable only artificially, by reducing the sauce to pure capsaicin, the chemical compound that causes the burn. There exists, available, on the open market, a hot sauce called Get Bitten Black Mamba Six, which packs a hit of six million Scovilles. To one drop of that, most people would want to add a couple hundred thousand drops of water. With a quart of milk, because capsaicin is fat soluble, so a dairy product better cuts the painful effect.

Even a sanely snappy hot sauce like Tabasco (2,500 to 5,000 Scovilles), or a more moderate popular sauce like Crystal (I don’t know how many Scovilles; I like it), can be run into the ground. Before you put any hot sauce into your oyster stew at Casamento’s, in New Orleans, you’ll want to ask your server for guidance, because a more vinegary sauce will curdle the stew. You might not want to add any hot sauce to gumbo, if it’s good gumbo. Leah Chase of Dooky Chase’s Restaurant, in New Orleans, stopped then president Barack Obama from adding hot sauce to the gumbo served him there, because if it had needed hot sauce, Mrs. Chase would have put it in there already.

However, and this is a big however, hot sauce does sharpen up a lot of good old originally-poor-folks’ food like rice and beans, it surely does.

In Louisiana, not in Minnesota. In Bolivia, not in Sweden. It may seem counterintuitive that hot sauce is big in places that are already hot. You’d think Minnesota would need hot sauce. But no, hot sauce is a hot-location thing.

Why is that? Not, as people will try to tell you, because it makes people sweat. Not, as people will try to tell you, because it masks the taste of spoiled food. No, it’s a pre-refrigeration thing. People in sultry climes, where microbes abound and breed fast, came evolutionarily to like the taste of hot-pepper sauce because it protected them from disease-causing bacteria. And the peppers were there already; they weren’t one invasive species brought in to stop another. People just had to take a little, whoof, a little hit.

Biologists have worked this out. Chiles kill microbes. But, by the way, they have established that hot sauce, however strong, is not the most powerful antibacterial spice. Garlic is, and then onion. Chile pepper is down at twelfth, just barely ahead of rosemary. Can you imagine old boys doing tequila shots and then bracing themselves against the challenge of rosemary hits?

It must be said that the biologists referred to above have inferably not consumed a lot of hot sauce in their lives, because they are at Cornell University, where it’s seldom very hot and often very cold. The Scoville scale itself was devised by Wilbur Lincoln Scoville, a product of, oddly enough, Bridgeport, Connecticut, which is a far piece from tropical. Maybe in the study of hot sauce, geographical detachment is an advantage.

HOUSTON IS THE CITY THAT TURNED “feeder roads,” those access lanes that run alongside major highways, into real estate gold mines. Fast-food franchises, big-box stores, and all manner of businesses that thrive in high-visibility locations flocked to the city’s elaborate grid of crisscrossing highways, complete with three interstates, an inner loop, an outer loop, and a few extra ten-lane limited-access thoroughfares thrown in for good measure. In a 1975 New Yorker article, Calvin Trillin coined the term “Houstonization,” which became a synonym for unsightly sprawl resulting from an utter disdain for urban planning.

Houston’s style, or lack thereof, made it the butt of jokes. It was (and still is) the only major American city without any zoning laws. Then the development frenzy came to an abrupt halt when the 1980s oil bust left real estate developers holding 187,000 unsold new homes and 116 million square feet of brand-new unrented commercial space. All that cheap real estate, along with the hot and sticky climate, the bustling port, and the piquant cuisine, made Houston attractive to immigrants from Mexico, Central America, Asia, and Africa, transforming what was once a typically biracial Southern city into a multicultural mecca. Today Houston has no “minorities” per se, but a population of Hispanics, Anglos, and residents of African or Asian descent, none of them constituting an ethnic majority. The fusion of ethnic foods emerging from this great bubbling gumbo of cultures inspired John T. Edge of the Southern Foodways Alliance to call Houston “the South’s new Creole city.”

Also, it turns out that a dense urban core connected to outlying suburbs by a hub-and-spoke rapid-transit system is fine for New York, Boston, and other cities that arose in the horse-and-buggy era. But forcing this model on Houston, Los Angeles, and cities of the American West that were built to accommodate automobiles is a matter of round pegs and square holes. In fact, after years of Houston’s drawing ridicule as the nation’s sorriest example of endless sprawl, Stephen Klineberg, a professor of sociology at Rice University, says that urban planners now hold up Houston as a model of a “Multicentered Metropolitan Region”—an urban area with lots of smaller, pedestrian-friendly town centers scattered throughout its own unique transportation grid.

So there: these days, they come to Houston to see how it’s done.

IF FISH HAD A LITERATURE, YOU WOULDN’T find the word water there, and in classic Southern fiction you won’t find humidity. It’s just assumed. What you will find is sweat. Not just atmospheric sweat, but sweat as the outward and visible sign of lust, fear, oppression, shame—all the eternal verities that people try to hide. Eudora Welty: “Sweat in the airless room, in the bed, rose and seemed to weaken and unstick the newspapered walls like steam from a kettle.” Tennessee Williams: “Your husband sweats more than any man I know and now I understand why.” In William Faulkner we find sweat like blood and sweat like tears; “sweet, sharp” horse sweat and “the ammonia-reek” of mule sweat; proprietary sweat, “to bind for life them who made the cotton to the land their sweat fell on.” And in “Dry September,” a story about a lynching, unnatural sweat: “Where their bodies touched one another they seemed to sweat dryly, for no more moisture came.”

Near warm water like the Gulf Stream and the Gulf of Mexico, hot air holds more water, or anyway more of the gases that are close to combining into water. Something like that. Let’s just say this: when you sweat into Southern air, it is already close to sopping. The 100-plus temperatures of, say, Arizona, may sound hot, Southerners will say, dismissively or wistfully, “but it’s that dry heat.” Some will maintain that humidity makes heat more bearable, because it brings out the sweat. But no. In Welty’s story “No Place for You, My Love,” a would-be-adulterous couple are “bathed in sweat and feeling the false coolness that brings.” What truly cools is rapid evaporation of sweat, not sweat that flows and lingers. Humidity makes sweat stick.

Which works not only in literature but in music. Louis Armstrong’s brow-mopping handkerchief was as much a trademark as his smile. James Brown was not only the hardest-working but the hardest-sweating man in show business. Muddy Waters paid this tribute to Howlin’ Wolf: “Some singers they’s cool . . . They too nice to sweat! But Howling Wolf now he works. He puts everything he’s got into his blues. And when he’s finished, man, he’s sweatin’. Feel my shirt, it’s soaked ain’t it? When Wolf finishes, his jacket’s like my shirt.”

Some of the grit of early blues recordings may derive directly from humidity. When RCA Victor was in New Orleans recording Rabbit Brown, a street guitarist and singer (he would also charge to row you out into Lake Pontchartrain, serenading as he rowed), for a 1928 album, the heat and humidity shorted some microphones out and made others sizzle and hum so much, they had to be packed in ice before use.

The old saying, of course, is that Southern ladies don’t sweat or even perspire, they glow. But in A Streetcar Named Desire, Blanche DuBois reassures her feckless suitor (a type that in Tennessee Williams always sweats heavily), that “perspiration is healthy. If people didn’t perspire they would die in five minutes.” Think of all the Southern things connected with humidity: porches, juleps, seersucker, halter tops, the blessed sweetness of a breeze, levees, powder, oppressive closeness, rot, the expression “freshen up,” crawfish, mosquitoes, fever, high ceilings, and heat that thickens, that casts a sheen, that comes in waves, that picks colors out of the air like a prism. Humidity humanizes the air, drawing out pheromones, bacteria, semidigested gravy, bacteria, gossip—the funk of what people breathe of each other. Today air-conditioning drastically limits the impact of humidity. So we’re all more comfortable. And what we get in the way of cutting-edge culture is Sweating Bullets, a book about the invention of PowerPoint.

WHAT BEGAN IN AUGUST 2005 AS A TROPICAL depression in the Bahamas went on to ravage parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, the deadliest U.S. hurricane in nearly eighty years, the costliest one ever to hit the United States, and what a former official with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration called “a defining moment in U.S. history.” See Katrina.

ADMITTEDLY, SOUTHERNERS ARE SOMETIMES known to prepare for natural disasters by stocking up on more liquor than plywood. But when the big storms hit, they’re hardly anything to celebrate. In 1900, the Great Galveston Hurricane’s 145-m.p.h. winds and massive storm surge killed an estimated eight thousand Texans (still the deadliest single day in U.S. history). Later hurricanes were given personalized names but were no better behaved: category-five Camille smashed the Gulf Coast and drowned hundreds from Mississippi to Virginia in 1969. Hugo turned coastal South Carolina upside down in 1989, and Andrew ravaged twenty-five thousand homes in Dade County, Florida, alone in 1992. As for 2005’s Katrina, well, we all watched live as she broke a beloved city—and our hearts. Hurricanes spin up from the tropics aimed at Southern shores (Florida is basically a big middle finger daring them to muss up its white-sand beaches), so, yes, living in the coastal South greatly increases the odds of meeting one of these monsters face-to-face. But it also means that your neighbor is likely to help dig you out of the debris, a coworker is likely to loan you a chainsaw, and a local church group is likely to hammer the last nail that gets you back on your feet. See Katrina.

(1891–1960)

WHILE LIVING IN HARLEM AT THE HEIGHT OF the Manhattan neighborhood’s storied artistic renaissance, Zora Neale Hurston was known for her parties. Langston Hughes, the poet Countee Cullen, and the actress and singer Ethel Waters would congregate in the living room, and Hurston would sit in her bedroom, typing. Although the folklorist’s legacy is complicated by her conservative politics and contrarian positions on race-related issues, the scene of Hurston writing in the vapor of celebrity comes closest to an image upon which biographers and critics can agree. Born in Alabama in 1891, Hurston at a very young age moved to Eatonville, Florida, a town founded by African American men. When she was thirteen, her mother died, forcing Hurston to ramble the South in search of work. At twenty-six, she declared herself sixteen again and enrolled in a Baltimore high school; she continued her studies at Howard University, where she joined up with literary figures and hatched a plan to move to Harlem. During the 1920s and 1930s, Hurston wrote short stories and conducted fieldwork. But her professional peak occurred about a decade later, when she published the novel Their Eyes Were Watching God to critical acclaim. Hurston never profited from her books, though; her neighbors in Fort Pierce, Florida, took up a collection for her burial in an unmarked grave after she died of a stroke in 1960.

SOME PEOPLE WILL TELL YOU THAT COOKS came up with hush puppies to keep hungry dogs from howling their way through fish fries. This backstory has its charms but probably isn’t true. For generations, humans have been too fond of these deep-fried balls of cornmeal batter to throw them to the dogs. Hush puppies unquestionably do quiet stomach rumblings, though, whether as bare-bones cornmeal croquettes or more elaborate appetizers spiked with onion, garlic, or whole kernels of corn. Commonly served alongside fried seafood and barbecue, they come in the shapes of golf balls and cheese curls and hark back to centuries of deep-fried cornbread tradition.