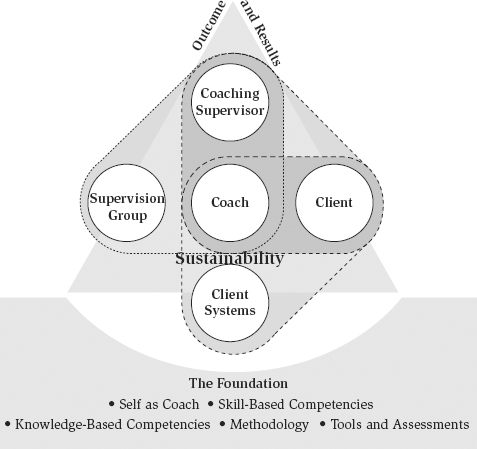

Figure 22.1 The Hudson Coach Supervision Model

© Hudson Institute of Santa Barbara.

Supervision has been an important staple in the developmental trajectory of professionals in several prominent fields of study, including psychology, medicine, counseling, and social work, providing a structured approach to ongoing development. The ten thousand–hour rule of mastery seems to be a simple enough equation, but it’s not merely the accumulation of hours of practice that creates mastery. Rather, it is the continuing work of reflecting on one’s skills, linking skills and practice to helpful theories and concepts, and tracking one’s developmental edges at each stage in the journey. Coaching supervision—the process of working with a masterful coach in order to take a step back and reflect on the ongoing development of the coach’s skills, the dynamics of the coaching session, the client dynamics relative to larger systems, and the coaching outcomes—serves an important role in the journey to mastery.

Korotov, Florent-Treacy, Kets de Vries, and Bernhardt (2012) note in their recent book on coaching that “no coach has a monopoly on wisdom. Many coaches still work without supervision, and many encounter similar coaching challenges.” We all need the support of a mirror to see our self and our work with more clarity. Supervision both supports and holds the coach’s feet to the fire, driving ongoing development, uncovering blind spots, examining failures as well as successes, and experiencing the parallel process at play in supervision that mirrors the coaching work.

Supervision can provide enormous value to a coach at several levels:

Most coaches practice in a predominantly one-on-one format, and this can be a lonely experience for a coach over time. Supervision not only builds capacity for the coach, but it represents a form of self-care for the practitioner as well. In Cziksentmihalyi’s terminology, supervision serves to keep the coach in flow, continually cultivating new territory for capacity building. In Howell’s model, supervision serves to move the coach more rapidly toward the state of unconscious competence.

Supervision spans a broad spectrum of activities:

The models previously covered in this book relative to self-as-coach domains (Figure 4.3), coach methodology (Figure 11.3), and the elements of masterful coaching (Figure 4.1) provide foundational reference points for the supervision work.

There are several types of supervision a coach can use, and we explore them next.

Solo supervision is essentially a practice of reflecting on each coaching session in a methodical manner that aligns with the development goals of the coach. It tracks the progress of the coaching work, including the rough edges and the difficult spots that need further exploration. Every coach ought to regularly engage in this first layer of supervision with self at all times. Portions of Clutterbuck’s seven conversations model (Figure 7.5) for reflection before, during, and after dialogue are particularly useful for solo supervision.

These questions are useful to consider in solo supervision:

Peer supervision could be in the form of a regular coaching buddy or a small group that meets on a regular basis. Many of the questions addressed in solo supervision prove equally useful here. These two additional questions take advantage of the presence of other coaches:

There is a growing trend toward formalized individual coach supervision. The U.K. coaching community has led the way on this front, and it is rapidly spreading to other parts of the globe. The process of individual coach supervision typically includes a regular meeting between supervisor (master coach) and coach, with a focus on examining coaching engagement relative to the coach’s development goals and all of the essential elements required to reach mastery.

All forms of supervision serve an important function in the journey to mastery, but in my estimation, group supervision has the potential to be the most effective. The group supervision model ideally runs the course of one to two years with a consistent group of participants. Group supervision has several unique advantages that I believe make it a particularly potent approach:

Once a coach has engaged in regular supervision over the course of one to two years, it can prove helpful to have a relationship with a supervisor that allows spot supervision when a particularly challenging situation emerges with a client. Spot supervision is a focused session, lasting fifteen to twenty minutes, in which the coach brings a specific coaching dilemma to a short just-in-time supervision session.

As organizations continue to create internal cadres of coaches, the use of external supervisors becomes more common in an effort to provide continued support and development for the coaching cadre and track the impact of the coaching on the overall organizational needs and goals.

Models of supervision are well developed in the field of psychology, and coach experts and researchers in the United Kingdom have adapted several of these models for use in the emerging field of coaching including Hawkins and Smith’s (2006) seven-eyed process model, Hay’s (2007) reflective practices in supervision, and Hawkins and Shohet’s (2006) developmental approach to supervision that all provide a useful support in supervision. Interestingly enough, while the United States was an early adopter of a supervision model in the field of psychology, we have been slow to research and adopt relevant models in the work of coaching.

At Hudson, we have developed an early model for coaching supervision (Figure 22.1) that specifically pertains to supervision within a group setting. In this model, the foundation of supervision rests on all that has been covered in this book: self as coach, skill-based competencies, theory-based competencies, sound methodology, and the tools and assessments that might apply to any particular situation. The ultimate goal of a successful coaching engagement is to create sufficient change so that the goals of the work are achieved in a sustainable fashion. This is also the final goal of all coach supervision. The coach in supervision is at the center of the model, and the dynamics of supervision are focused in three constellations. We use the term supervisor in this model to refer to the internal or external master coach who serves as the supervisor for the coach, client refers to the individual seeking coaching, and client system refers to the organization or environment in which the client works.

The coach’s understanding of this primary system—the coach’s role in the interface between coach, client, and client’s organization and the tension points and complexities found in this constellation—is at the heart of the work in supervision.

Questions for the coach in supervision relative to this constellation might include these:

This vignette highlights the natural dynamics that occur within the coach–client–client system triangle and in the context of the supervision group provides ample opportunity to explore the situation through these lenses:

The coach and the supervisor’s understanding of this essential system—the nature of the working alliance with the client, the awareness of transference and countertransference dynamics in this constellation, and the ultimate outcomes that have an impact on the client’s success—is the next important layer in the supervision work.

Questions for both the supervisor and the coach in this constellation include these:

This is only a first step in Marge’s work (see the following case example), but it points out the power of the coach–client–coach supervisor in uncovering new layers of awareness that will help the coach’s work with clients. Each member of a supervision group has a development plan, and if the themes of pace and presence weren’t already on Marge’s plan, they will become an important part of it going forward.

The final layer of the supervision constellation lies in the awareness and use of the dynamics at play in the supervision group as it relates to themes for both the members of the group and the supervisor.

Questions for the coach-in-supervision might include these:

This next-level layering of Marge’s awareness relative to the triangle of the supervision group and coach supervisor creates a powerful epiphany for Marge in the moment. It also provides the entire group with an in-the-moment experience of the power of sharing observations, providing feedback to one another, and attending to one’s internal experience and using it in the service of the coaching work.

These brief vignettes provide a glimpse into the potent capacity for development that a supervision group provides for all members of the group and the impact the supervision work has on the ultimate effectiveness of the coaching with the client and the larger systems of the client. In essence, supervision becomes a dynamic process for providing quality control to the client and client organizations through the continual focus of the coach’s development.