After the sewing up is finished, there are still plenty of things to do on a sweater. While you may not be interested in adding unnecessary embellishments, borders deserve your attention because of the important roles they play in supporting the garment and in making its edges behave the way they should. You also have the opportunity to add collars, pockets, cords, and ruffles. Then, for the final detailing, block the seams and anything else you want to look particularly good.

Conventional bottom-up and top-down garments knit with shaped armholes and necklines usually are finished off by adding borders around the neck and around sleeveless armholes. Cardigans require borders along both sides of the front, frequently with buttons and buttonholes. All of these borders are very, very noticeable. Poorly executed borders can make a garment that is otherwise perfect look vile.

There are several challenges in adding borders:

To better understand the important role of borders, especially the neck border, take a look at Changing the Borders in chapter 3. Well-made neck and armhole borders are essential to the structure and fit of sweaters and vests, and are in such prominent positions that any failings in proportion or execution will be immediately noticeable. It may require several attempts, but it’s worth the effort to unravel and do them over until they are exactly right.

This section covers picking up stitches along the straight or shaped edge of the knitting, but assumes that it’s just a normal edge. If you’re working with a cut edge, because of adjustments for size or because you’ve steeked the garment, see Finishing the Cut Edges in chapter 6.

In stockinette or a stockinette-based fabric, always work 1 full stitch in from the edge — this will be easy because you kept 1 or 2 edge stitches in stockinette and did any increasing, decreasing, and patterning farther away from the edge, so they won’t get in the way of picking up the stitches (see Planning for the Best Edges and Seams in chapter 2). Always pick up stitches by inserting the needle through the fabric and knitting up a new stitch through the edge of the fabric using your working yarn.

If you worked the garment in garter stitch, you may have worked the garter stitch all the way to the edge, or you may have worked slipped-stitch edges to make it easy to pick up 1 stitch in every other row. Depending on how you handled your edge stitches, you have several pickup options.

Picking up a whole stitch from the edge in stockinette. In this photo, the knitter is working from the bound-off edge toward the cast on. When working in either direction, you can be sure you’re picking up a whole stitch from the edge by inserting the tip of the needle underneath both of the strands that make up the stitch.

Picking up a whole stitch from the edge in garter stitch. Pick up under the stitches between the ridges.

Picking up half a stitch from the edge in garter stitch. If the edge is loose, pick up in the little knot at the end of each ridge; otherwise, pick up in the long, loose stitch between each ridge.

Picking up a whole stitch along a slipped edge in garter stitch. This can sometimes look loose.

Picking up a half stitch from the edge along a slipped edge in garter stitch. Picking up under the back half of the stitch creates a neat ropelike detail. Picking up under the front half of the stitch hides the edge stitch completely.

Your pattern may tell you how many stitches to pick up, but this isn’t necessarily the number you need to pick up along the edge of your sweater. Rather, it’s the number that the designer estimates will fit along the edge of the size you’re making, assuming you didn’t make any changes (intentional or unintentional) in the length or width. Alternatively, the pattern may tell you how often to pick up along the edge (for example, 3 stitches for every 4 rows) and what multiple of stitches you need to end up with (for example, a multiple of 4 stitches plus 2 to work K2, P2 ribbing). This is much more likely to result in a successful border (and it’s what I recommend that you actually do), because it takes into account any changes that may have been made in your particular sweater. What neither of these instructions allows for is significant differences in tension between the original designer and the knitter. For example, if you work ribbing much looser than the designer expects, your ribbing will end up the wrong size. (If you think you might have this problem, see Needle Size Makes a Difference.) These factors could make your sweater different enough from the designer’s concept that the instructions might not work for you.

You should be familiar with the basic proportions for picking up the right number of stitches along the edge of the basic fabrics (stockinette and garter) to make standard ribbed or garter stitch borders. In most cases, you can substitute these for pattern instructions that tell you to pick up a certain number of stitches, to make a border that neither flares out nor gathers the edge of the fabric.

For ribbed borders attached to stockinette stitch, pick up about 3 stitches for every 4 rows along the side and diagonal edges of an opening, and 1 stitch in every stitch along a bound-off or cast-on edge. To pick up along a curved edge like an armhole or neckline, you’ll need to pick up along all three types of edges: horizontal (along a bound-off or cast-on edge), diagonal (along increases and decreases), and vertical (along the side). (See photos here.)

For garter stitch borders attached to a garter stitch base fabric, pick up 1 stitch for every 2 rows (which is the same as picking up 1 stitch for every ridge) along the side of the fabric, as shown in photos at left.

For other pattern stitches. The proportions above are designed to work when you are adding a ribbed border to a stockinette garment or a garter stitch border to a garter stitch garment. In other situations, they most likely will not work properly. You can figure out the correct number of stitches for your border by working a separate gauge swatch in the border pattern. See Getting Neck Borders Right in chapter 3 for how to plan a border with exactly the right number of stitches.

A final consideration is that you need to adjust the number of stitches to fit the border pattern. If you find it difficult to pick up the correct number of stitches, it’s best to pick up a few more than you need, and then decrease to the correct stitch count on the first row or round of your border. If you come up just 1 or 2 stitches short when picking up, you can increase to make the adjustment.

I have commented in several places within this book that other fibers just don’t behave the same as wool or wool-blend yarns. This is especially noticeable in borders. Because they are inelastic and have less “memory” than wool, borders in other fibers tend to stretch out of shape. See Fiber Content and the Finished Fabric in chapter 1 for a discussion of this problem. If your borders don’t seem to be behaving the way they should, especially if they are lethargic and enervated, try some of the suggestions in Beginning with the Very Best Borders in chapter 2, Changing the Borders in chapter 3, or in the following pages.

A curved edge with ribbing in a variety of fibers (top to bottom): silk, a mohair/wool blend, a cotton/wool blend, wool, and a silk/wool blend. The more wool in the yarn, the more the border pulls in naturally.

The same curved edge in wool with four different borders (top to bottom): K2, P2 ribbing; K1, P1 ribbing; Open Star Stitch; Baby Cable Ribbing. Open Star Stitch flares beyond the edge of the swatch, a sign that a few stitches need to be decreased at the upper edge to shape it properly. Notice also how the K2, P2 ribbing naturally pulls in more than K1, P1 ribbing.

Some pattern stitches are more elastic and have more memory than others. Ribbing will stretch and tends to return to its original width; K2, P2 and K3, P3 ribbings are better at this than K1, P1. Ribbing with stitches twisted by working into the back loop will have more memory than standard ribbing. Pattern stitches that are not ribbed tend to be less elastic (don’t stretch as much as ribbing) and to have poorer memory (so they stretch out of shape). Because of these inherent properties, it’s easier to make a ribbed border that looks good and behaves well. If you’re working in anything other than a basic ribbing, you’ll need to size your border carefully, plan for it to stretch, and, if it’s along a curved edge, you may need to shape it for best results. (See photos, here.)

Borders worked with different-size needles. In this silk yarn, the border at the top was worked on needles the same size as the base fabric. The one in the center was worked on needles two sizes smaller, and the one on the bottom was worked on needles four sizes smaller. Notice that the border stitches on the bottom are a little tighter and neater and that the border pulls in just a little at both ends (which is what you want in a perfect border), rather than flaring at one end like the border at the top.

You may have picked up exactly the right number of stitches but still run into a problem if your ribbing tends to be looser or tighter than the norm. You can deal with this by adjusting the needle size. Use a smaller needle to make the ribbing just a bit tighter, and a larger one to make it just a bit looser. You can tell you’ve got the right needle size when the knit stitches in K1, P1 ribbing look the same size as your knit stitches in stockinette.

Remember that most ribbed borders are worked on needles two sizes smaller than the body of a stockinette stitch garment. This serves two purposes: it makes the stitches a little smaller so they look neater, and it makes the border a little firmer so it retains its shape. Even if the instructions don’t say to do so, you can go ahead and work the border on smaller needles to improve the look and behavior of your border.

When working in any fiber other than wool or a wool blend, you can significantly improve the behavior of ribbed borders by using needles three or four sizes smaller. They’ll hold their shape better and look neater.

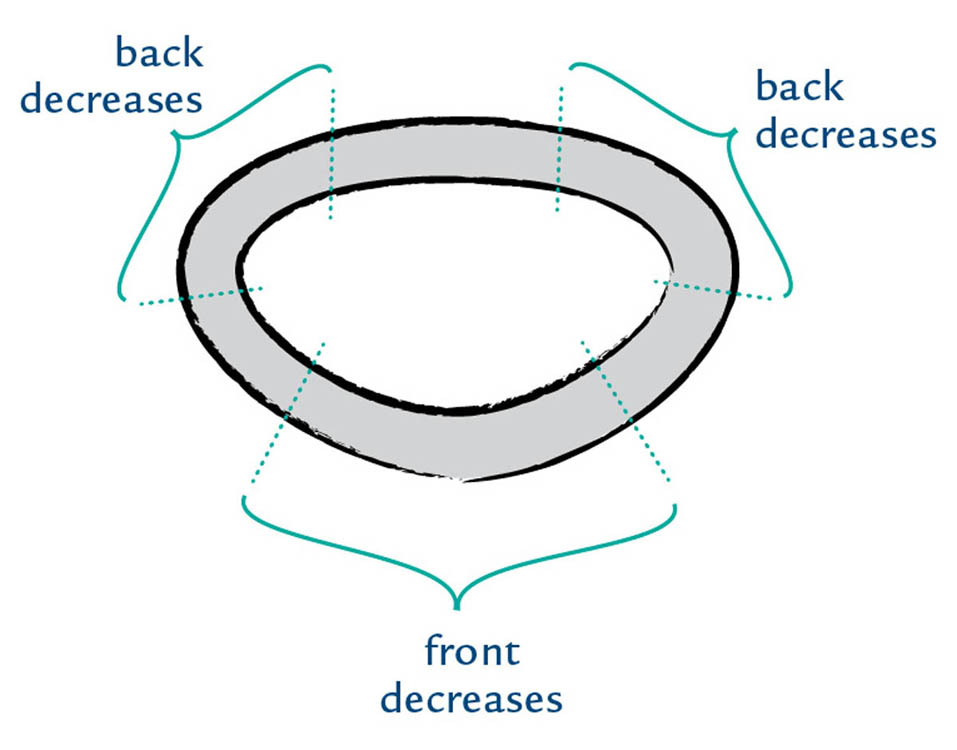

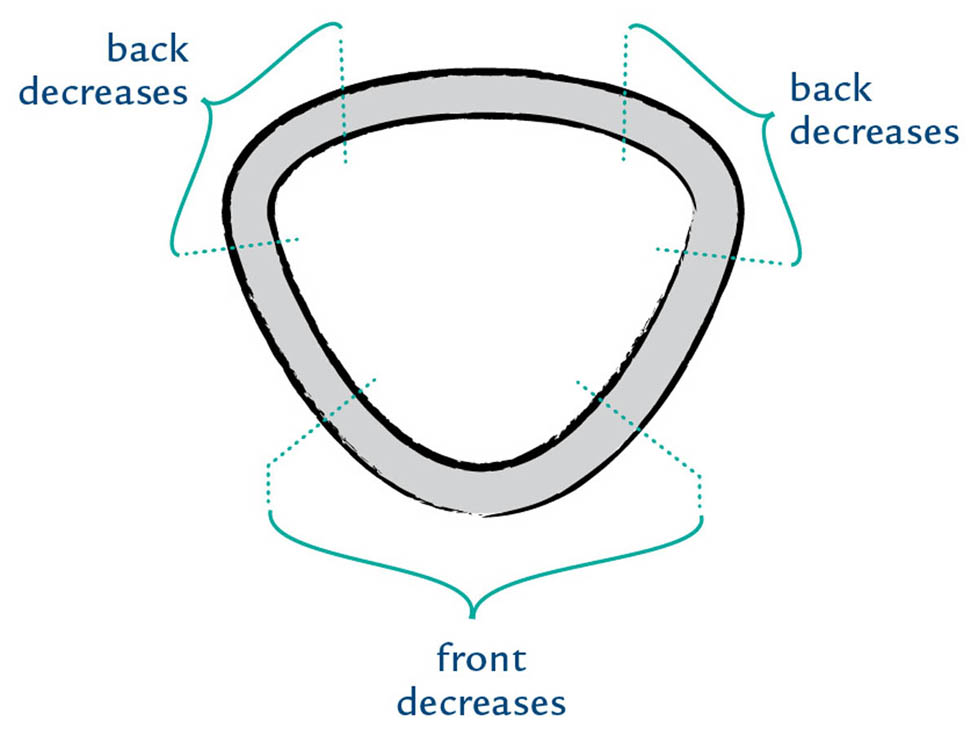

Borders along a straight edge (like the bottom of a sweater) are very straightforward — you need to make sure only that they are worked on the correct number of stitches and with the correct needle size and they’ll come out fine. Borders along shaped edges like necklines and armholes have the added challenge that they need to fit around the inside of a circle, square, or V. Shaped bottom edges, like a curved shirt tail or a pointed vest detail, require the border to fit properly around the outside of a curve or corner.

V- and square-necked openings have corners, and your border needs to fit perfectly into those corners or it won’t lie flat. You can work these as mitered corners, making decreases at the corner points, or you can work each of the straight sections flat, overlap them, and sew down the ends. For examples of these two treatments, see the photos of V-Neck borders in chapter 3.

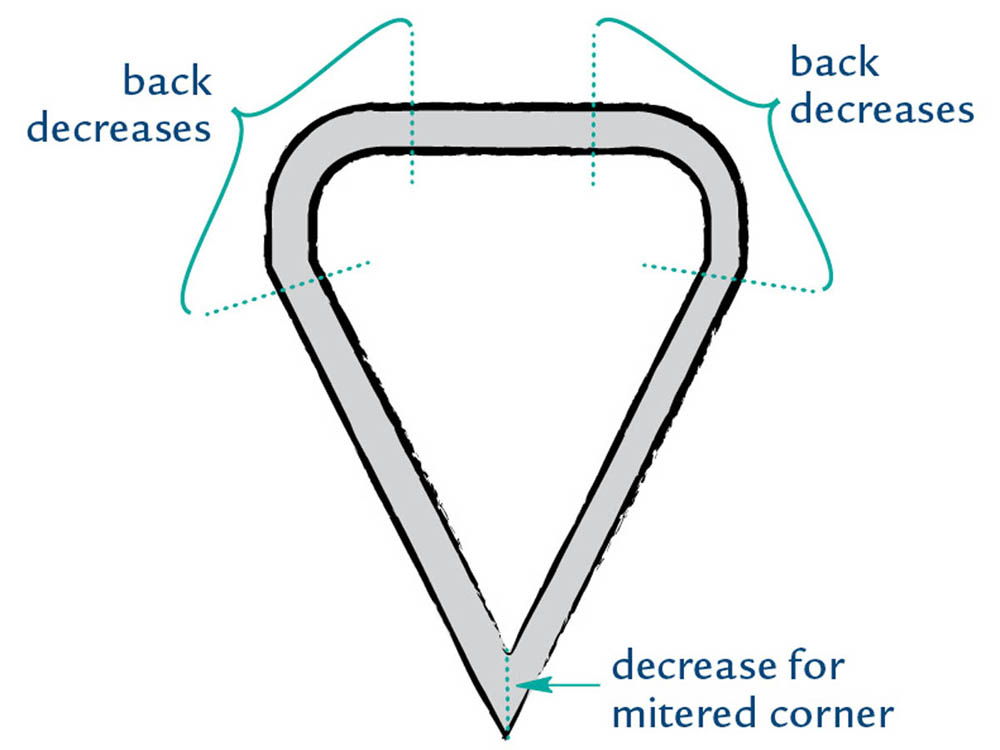

Mitered corners on a neckline require that you decrease 2 stitches at each corner on each decrease row or round. You can do this with a double decrease like s2kp2, or you can work a pair of symmetrical decreases on either side of the corner stitch (see Symmetrical Increases and Decreases in chapter 2). To match the angle of the corner, you’ll need to decrease at exactly the right rate. How often you work the decreases will depend on the angle of the corner and the pattern stitch in your border. For a low V-neck, you may need to decrease on 2 out of 3 rows or rounds, or on 3 out of 4. For a higher V-neck or a right-angle corner, you may need to decrease on every other row or round.

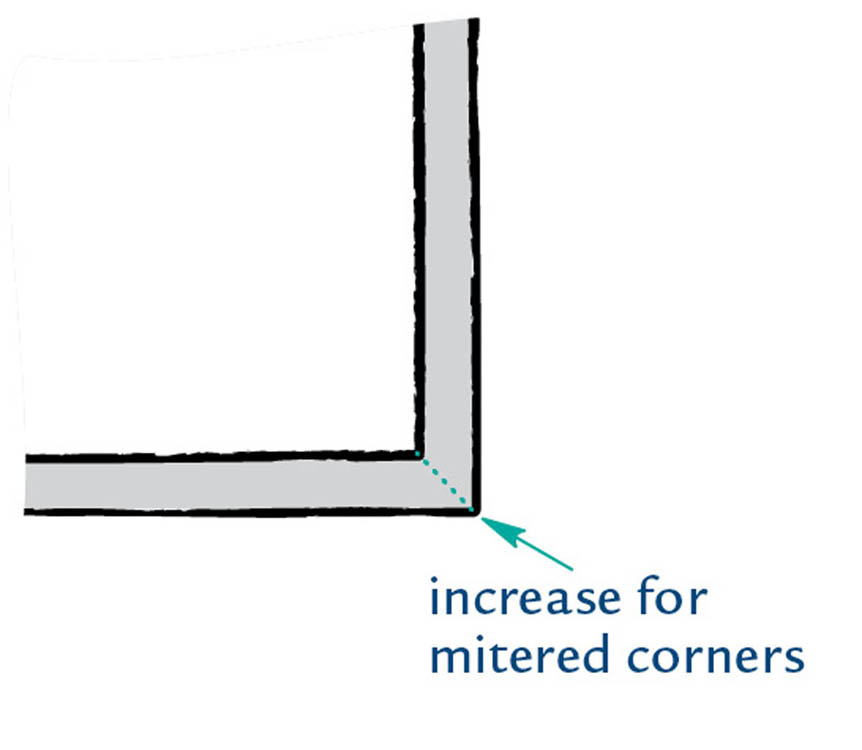

If you need to add a border to an outside corner, for example on a squared shirt tail, a collar, or at the top or bottom corner of a cardigan front, you can work a double increase (such as K-yo-K in a single stitch) or a pair of symmetrical increases on either side of the corner stitch (see Symmetrical Increases and Decreases in chapter 2). If the border is worked in garter stitch, then work the increases every other row or round. In other pattern stitches, you’ll need to increase a little more often to make the corner lie flat — try increasing on 2 out of 3 rows or 3 out of 4 rows. Be sure to bind off loosely, perhaps working your final corner increase while binding off, so that the edge lies flat.

Outside corner border. Borders worked on outside corners, using the K-yo-K increase (left) and paired M1 increases on either side of corner stitch (right).

V-neck border. If desired, decreases can also be worked at the curved back corners of a V-neck to adjust the fit and prevent flaring.

Square neck border. The corner at left was worked using two separate but symmetrical decreases. The corner at right was worked with the double decrease s2kp2.

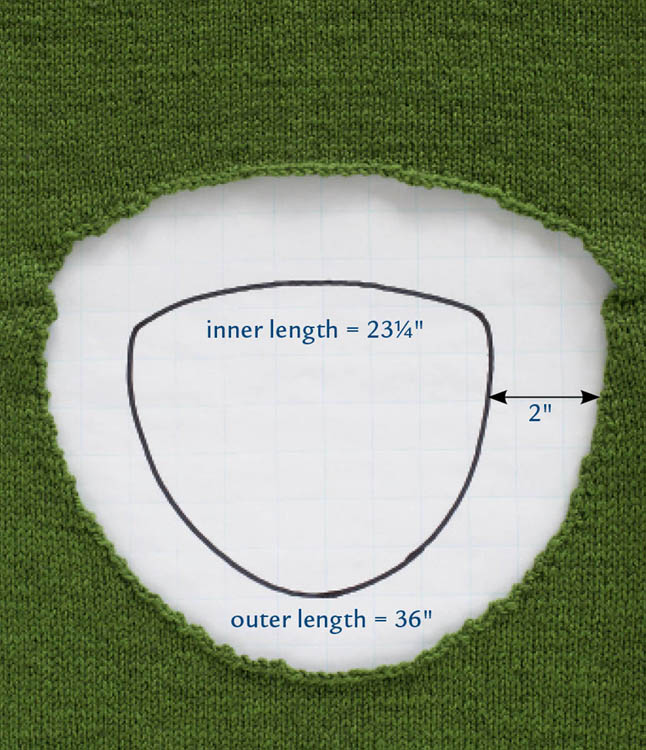

You can ensure that the border fits perfectly in a round neck opening, an armhole opening, or around a curved shirt tail by shaping it, planning for a smaller number of stitches around the inner edge of the curve and a larger number of stitches around the outer edge of the curve.

To make a shaped border you need to know how many stitches there should be where the border meets the edge of the garment and the number of stitches at the outer edge of the border. For a neck border, make sure that the measurement at the outer edge will be long enough to fit over the wearer’s head. You also need to integrate the shaping with the pattern stitch for your border, and place the shaping to fit the curved sections of the edge the border is attached to. See Case Study #8-1, for details.

Stitches to pick up = 36" × 41⁄2 stitches per inch = 162 stitches

Decrease to: 231⁄4" × 41⁄2 stitches per inch = 105

How many stitches to decrease = 162 – 105 = 57 (about 1⁄3)

Round neck border

Scoop neck border

Outside curved border

Garter stitch borders are easier to shape because you can decrease throughout and still maintain the pattern. Note that if you bind off firmly, you may be able to make a shorter outer edge without doing all of the planned decreases. If you’re making an outer curved edge, like on a shirt tail or collar, be careful to bind off loosely instead.

On the scoop neck from our example, 9 decreases were worked in the front section of the border on the 2nd purled round, and 48 were worked in the purled round following the pattern stitch to reach our total of 57 decreases. The bind off was worked in purl to mirror the 2 purled rounds at the beginning of the border.

On this round neck, the border was worked flat, because that’s easier in garter stitch, and then seamed at one shoulder. On the first right-side row, 6 stitches were decreased evenly spaced to reduce the total number to an even multiple of eight. On all the subsequent right-side rows, 8 stitches were decreased, staggering the decreases so they never lined up with earlier decreases. Staggering the decreases ensures that the border will be curved.

The front borders of cardigans, which can be plain or can provide space for buttons, buttonholes, and other fastenings, support the front edges. They need to be exactly the correct length and to lie flat. Blocking is required to ensure that the fronts are indeed the correct length, their corners are square, and they are perfectly flat. Buttonholes present their own problems — it’s hard to make holes just the right size for the buttons.

Front borders can most easily be worked perpendicular to the fronts, by picking up stitches all along the front edge and then working out. Or, they can be worked in a long strip from top to bottom, either sewing this strip to the front after it is complete, or by Knitting On in chapter 6.

Assuming you are applying a ribbed border to a stockinette stitch garment, you’ll usually use a needle two sizes smaller than that used for the body of the garment when you work the border. This makes the ribbed stitches look neater (loose ribbing can look sloppy) and helps the border retain its shape when worn and stretched.

Remember, though, that all knitters are individuals, and the knitting that comes off their needles can vary a great deal. If your ribbing tends to be very loose, you might need an even smaller needle. If your ribbing always tends to be tight, you might need a larger needle. And, if you’re making a border that’s not ribbed on a garment that’s not stockinette, you may need to adjust for the difference in gauge produced by whatever knitted fabrics you are using instead. The best way to determine the needle size for the borders in your particular situation is to test it out on your swatch as described in Swatching to Refine the Details.

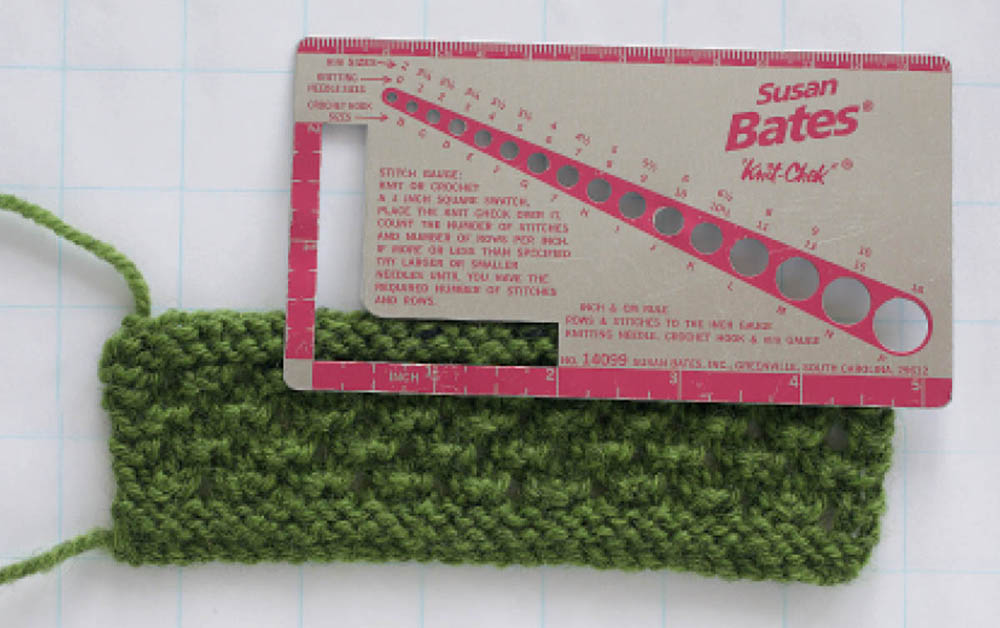

Before making a border worked perpendicular to the front, work a swatch in the ribbed (or other) pattern you plan to use for the front borders. Be sure to use the size needle you plan to use for the actual border. Measure the border swatch slightly stretched to determine the stitch gauge. Measure the front edge and multiply by the stitch gauge to determine the number of stitches you need to pick up for the border. Adjust the number of stitches to center your pattern and to make both ends look good.

When ribbing is at rest, it naturally scrunches up so that the knit ribs hide the purl ribs. When blocking your swatch, stretch it sideways just enough so that the purl ribs show in nice proportion to the knit ribs. Don’t stretch it to its maximum possible length, which will remove all its elasticity. You want it to still be elastic after blocking so that it can stretch and rebound as ribbing naturally does. If your border isn’t ribbed, then stretch it just enough during blocking so that the pattern stitch looks its best. To do this, you may need to stretch it a bit in both dimensions. As with ribbed borders, you don’t want to max out the stretch; treat your border gently.

If you’ll be working your border in a long strip with the side attached to the front of your garment, you’ll need to be sure it’s the correct length. Work a swatch in the ribbed (or other) pattern you want to use for the front borders. It should be the same width you plan for the finished border and at least 6 inches long. Be sure to use the size needle you’ll use for the actual border; usually this will be two sizes smaller than that used for the body of the garment. Measure the border swatch slightly stretched to determine the row gauge. Measure the front edge and multiply by the row gauge to determine the total number of rows for the border. If you plan to attach the border to the body as you go, count the number of rows in the front to determine how often you’ll knit up a stitch along the edge to attach the border smoothly to the garment.

How you handle the end stitches of a border worked perpendicular to the body depends on what will happen next to these stitches. Consider whether they will be the finished edge of the knitting, or whether a neck or bottom border will be picked up along them.

If the ends of the borders will be hidden by another border, you don’t need to worry about how they look, so long as you can pick up neatly across them. You may, however, want to consider how the border will look once the end stitch disappears behind the adjacent border. When the ends of the border will be exposed, you’ll want to make those edge stitches look as good as you possibly can. You have lots of options for this tiny detail. (See below for the referenced illustrations).

Ribbed border with slipped-stitch edge

K1, P1 border with an extra knit stitch at the end

K2, P2 border with 3 knit stitches at the edge

Ribbed bottom border with 1 stitch in garter stitch at each end to prevent curling. Notice that where this border crosses the ends of the two side borders, a knit stitch neatly abuts it. The side borders were worked with an extra knit stitch at each end, which disappeared to the wrong side when the bottom border was added.

2-stitch corded edge

There will be times when you want the inside of the front borders to look just as good as the outside. All cardigans will flop open sometimes when they aren’t buttoned shut, or you may want to make a garment that’s fully reversible. To accomplish this, pick up and begin your border exactly as described for Creating a Binding to Enclose an Edge. After working just 1 or 2 rounds, join the two layers together and continue in a single layer.

The picked-up edge of the border looks the same on the inside and the outside.

Double-thickness borders along the fronts of a cardigan will keep their shape better and look and feel more substantial. If you want to make borders that are plain stockinette, doubled borders will allow you to do this without the borders curling. On the other hand, a double-thickness border can be very bulky if worked in worsted-weight or heavier yarns. To make a double-thickness border, use any of the options in Bindings and Facings to Enclose Edges. Remember to work any buttonholes in both layers of the border.

Another option for covering the edge inside and out is to work a yarnover between each stitch as you pick up along the edge, then create a 1-row binding using tubular knitting. The pickup row tends to look loose and messy unless you control the tension while picking up, but you can easily do this by changing needle sizes.

The finish on the wrong side will not be as neat as working a full binding (see Starting Double, Ending Single), but this is quicker and easier to execute and you don’t need a second needle to do it. While shown here on a collar, this is also a great technique for making the pickup row on sweater fronts reversible.

This collar was picked up with the inside of the garment facing the knitter, so the “right side” is shown where the collar joins the garment at the left and around the back neck. The “wrong side” is shown under the collar at right.

Buttons (and their holes) can be problematic in knitting. It can be so difficult to find the perfect button to match a garment that it’s sometimes best to choose the buttons first, then buy the yarn. When you purchase buttons, choose those that can be cleaned the same way as the yarn. For dry-clean-only yarn, choose buttons that can be dry cleaned. For washable yarn, choose buttons that can be washed.

Making holes that actually fit the buttons, so the garment can be closed easily and will stay closed, can also be tricky. Spacing the holes evenly along the front presents an additional challenge. You can work the buttonholes while making the front band, or you can add them later. In all cases, however, before you begin working the holes, you need to plan how they will be made and where they will be placed.

A final difficulty — one that rears its ugly head even when the buttonholes are perfectly placed and executed — is that knitting stretches. This can cause the front to stretch between the buttonholes, making curved gaps all along the center front. The only way to avoid this is to sew some nonstretchy material (like grosgrain ribbon) along the inside to stabilize the fronts, but it can also be mitigated by using more buttons and placing them closer together.

It’s best to work the button border first; based on that, figure out where the buttonholes will fall on the opposite front.

On horizontal borders (worked perpendicular to the body of the garment), determine ahead of time what row or rows of the border the buttonholes will be worked on.

On vertical borders, you’ll work a narrow strip from end to end, adding one buttonhole at a time.

There are many different kinds of buttonholes to choose from. Make your selection based on how they look and whether they fit your button. Test your buttonholes by adding a button band to your swatch. This gives you the opportunity to try several different buttonholes and to make them different sizes. Make sure the hole is barely big enough for the button to pass through. The instructions for all the Buttonholes shown here are in the appendix.

The most basic buttonhole is a simple eyelet, which will work anywhere. This is the smallest hole you can make, and it is especially good for bulky yarns or for tiny buttons on baby clothes. It looks great placed in a purled rib of K1, P1 ribbing (B).

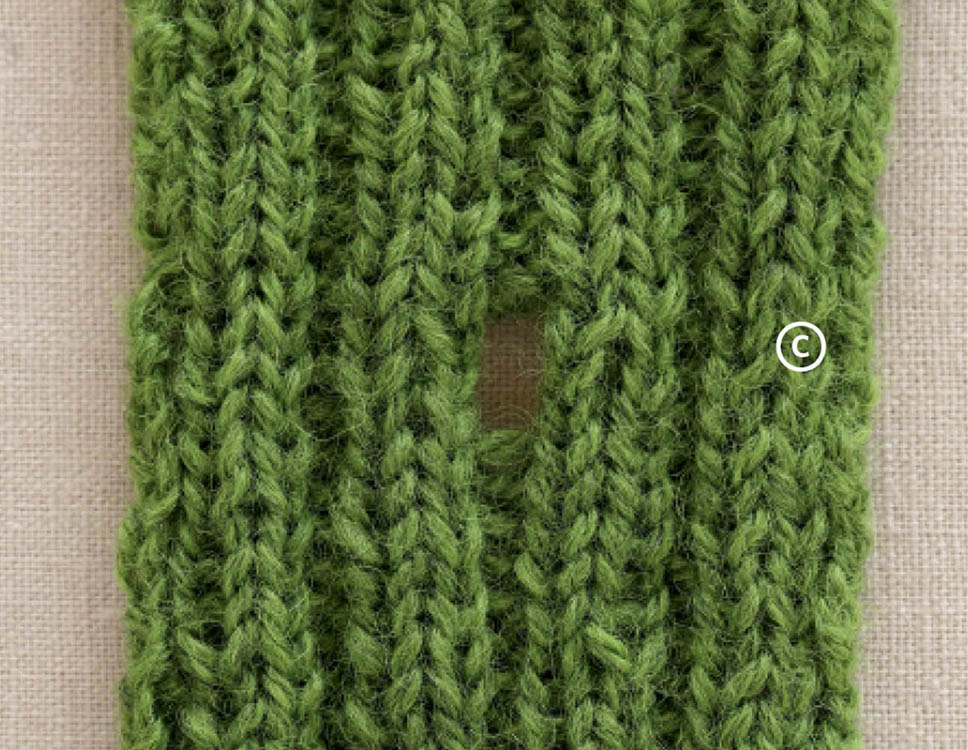

Vertical buttonholes are least noticeable in ribbing when placed in a purl rib. You can choose versions that integrate well with both K1, P1 ribbing and K2, P2 ribbing (A, C).

Horizontal buttonholes are especially good in garter stitch, where they can be hidden in the valley between two ridges. These include the afterthought buttonhole (D), the one-row buttonhole (E), and the three-row buttonhole (F). The first is very convenient if you discover you didn’t make a buttonhole when you should have, or if you just don’t want to worry about the buttonholes while working your bands. The second is a little more complicated than most buttonholes, because the yarn is woven in and out between the stitches to prevent the buttonhole from stretching.

I-cord buttonholes are very versatile, easy to position, and are added when cording is applied to the edge of the garment. They work best when you first work a plain cord along the edge, then make the buttonholes while attaching a second cord. To make a slit buttonhole, when you reach the point where the buttonhole should start, stop attaching the cord. Instead, just work plain I-cord for the length of the buttonhole, then begin attaching it again. To make a loop buttonhole, do the same, but work a longer section of detached cord, and when you are ready to attach it, pick up your next stitch in the same spot you picked up the last stitch before starting the loop. (See applied I-cord instructions in the appendix.)

Buttonholes for K1, P1 ribbing. Vertical buttonhole A, eyelet buttonhole B

Vertical buttonhole for K2, P2 ribbing

Horizontal buttonholes. Afterthought D, one-row E, three-row F

Loop and slit buttonholes made with applied I-cord. First the burgundy cord was attached, then the buttonholes were made while attaching the pink cord.

If you end up with a buttonhole that’s too loose, use matching yarn to sew across one or both ends to make the buttonhole shorter and weave the yarn in and out along both sides of the opening to prevent stretching. You can also work Buttonhole Stitch around the buttonhole using yarn or sewing thread.

Sew the buttons on along the front, positioned so they line up with your buttonholes.

If the holes in the buttons are large enough, use a tapestry needle and the yarn from the project to attach them. As you work along the front, don’t cut the yarn between each button; instead, weave the yarn in and out on the back of the fabric (just as if you were weaving in an end), until you get to the position for the next button. This ultimately is less work than weaving in two ends of yarn for every button. (See photo here.)

If the hole in the button is too small for a tapestry needle threaded with yarn to pass through, use a sewing needle and thread.

Shank buttons (with a loop attached to the back) allow you to button up thick knitted fabric without compressing the fabric. If you are attaching buttons with holes through them to a thick fabric, create a sewn shank between the button and the fabric. Using thin yarn or sewing thread, sew the button on loosely, leaving space between the button and the fabric; wrap around the strands between the button and the fabric a few times, then pull through to the back and secure.

Make a shank with sewing thread to accommodate the thickness of the knitted fabric.

If the knitted fabric is loose, so that any tension on the buttons pulls the strands of yarn leaving gaps, you can provide reinforcement by sewing a small flat button to the back of the fabric. When you attach your buttons, sew through the one on the back, the fabric, and the button on the front all at the same time.

If you have been unable to purchase buttons that can be laundered or dry cleaned with the sweater, plan to remove and replace them every time the sweater gets dirty and needs to be cleaned. This can be annoying and time consuming if you have to cut off and re-sew the buttons each time, but there are a few alternatives.

Buttons attached with button pins

On the right side, you shouldn’t be able to tell how the buttons were attached.

Even if you pick up exactly the right number of stitches as described previously (see How and Where to Pick Up the Border Stitches), the point where the border meets the garment may still look messy and inconsistent.

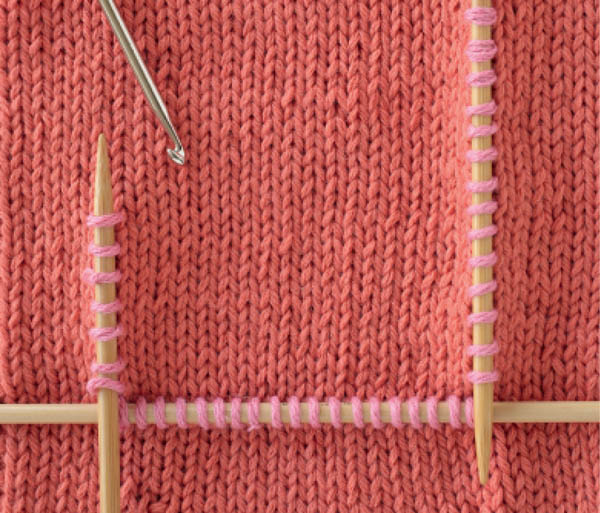

When picking up stitches along an edge, especially a curved edge, one issue is that you need to pick up unevenly. For example, when picking up for ribbing along the side of stockinette stitch, you’ll usually pick up 3 stitches for every 4 rows of the base fabric. In some yarns, the skipped rows will stand out like a sore thumb, and it will look like you didn’t know how to pick up evenly. To avoid this problem, pick up 1 stitch consistently in every stitch and every row around an opening or along an edge, then decrease to the correct number of stitches on the first row or round of your border. The picked-up stitches will look even, and you’ll end up with the correct number of stitches for your border. If the picked-up stitches or the whole picked-up row looks looser than the rest of the border, you can make it look neater by using a needle one size smaller for the pickup row than for the border itself.

A second issue is that, especially along a curved edge, there are variations in how you pick up stitches. Some will be in the top of columns of stitches, some between stitches, and some along the diagonals formed by shaping a neckline or armhole. Any variation like this immediately attracts our attention. To camouflage these variations, after you pick up for the border, work reverse stockinette for 1 or 2 rows or rounds before beginning the pattern stitch for your border. The even ridge of purled stitches will then be what people notice, rather than the uneven picked-up stitches. You can frame your border with reverse stockinette by working reverse stockinette to match at the outer edge.

Take into account, before you decide to finish the edges with an enclosed border, that the edge will be a double or triple thickness. If the edge has been cut, then the original fabric will extend into the double thickness of the border, making three layers. If the edge has not been cut, there will still be the double layer of the border. A double thickness may be okay in worsted-weight yarn, but a triple thickness in worsted-weight yarn is very bulky. This may be an advantage around a neckline or cuffs, providing extra stability and warmth. In other locations, like the front opening or around armholes, it may be less comfortable and less attractive. Because of this, enclosed edges are really best reserved for garments made from thinner yarns and avoided when using thicker yarns.

To make a doubled border, pick up stitches along the edge as usual and work the border as usual. When it is the width you want, make a fold line by working 1 or 2 rows or rounds in reverse stockinette. This will make a ridge that, when folded, forms a neat edge. Work either in stockinette or ribbing until the second half of the border is the same width as the first. Attach the edge to the inside just as for a hem (see Hems).

If you need buttonholes in a doubled border, you must work the opening twice for each buttonhole: once in the first half and then in the identical position in the second half, so that the two openings line up when the border is folded. You can leave the two layers separate and just slip the button through both, or you can use buttonhole stitch to join the two layers. Another option is to make matching afterthought buttonholes in each layer, and then instead of the sewn bind off, use Kitchener stitch around the opening to join the two layers. (For all of these techniques, see the Appendix.)

Sewing down a doubled border

Bindings achieve the same end as doubled borders, but both layers are worked at the same time and then joined when you bind off. To begin a binding, pick up and knit stitches along the edge as usual, using a circular needle. Be sure to work loosely while picking up, or use a larger needle to ensure that the picked-up stitches are loose enough. At the end of the first side, work an M1 with the working yarn. (See photo 1, below.)

Turn the garment over so the wrong side is facing you. Using a second circular needle, pick up and knit 1 stitch under the strand between each of the stitches you picked up on the right side. After you’ve picked up all the stitches on the wrong side, work another M1 at the end of this second needle. You should end up with 1 fewer stitch than on the first side. (See photo 2, below.)

Work around on the two circular needles (see the instructions for working on two circular needles in the appendix) until the border is the desired width. If there are any cut ends along the edge to be enclosed, trim them, then hold the two layers together and work Three-Needle Bind Off to secure the live stitches and join the two layers at the same time. (See photo 3, below.)

If desired, you can join the two layers together without binding off, and continue in a single layer. (See photo 4, below.) This is an excellent way to join a decorative panel with lots of ends to another section of a sweater, producing a clean finish on both the inside and the outside of the garment. Before starting the binding, be sure to knot the ends securely or hand- or machine-stitch along the edge so there’s no chance they’ll unravel. When the binding is wide enough, hold the two needles together as if you were going to work three-needle bind off, but just knit the front and back layers together. For a reversible binding, alternately knit and purl as you work across joining the layers.

As for a doubled border, if you need buttonholes in a binding, you’ll have to work the opening twice for each buttonhole: once on the outer layer and once in the identical position in the inner layer so that the two openings line up. You can use buttonhole stitch to join the two layers, or leave the two layers separate and just slip the button through both. Note that if a doubled border is covering a lot of cut ends or a cut edge, the presence of the yarn or knitted fabric between the two layers will make it difficult, if not impossible, to pass a button through.

Facings differ from borders in that they are located on the inside of the garment. For example, a facing can be worked at the top of a sleeve to completely enclose the cut edge of a steeked armhole opening, or it can cover the inside of a neckline that has been cut after the knitting is finished (rather than shaped during the knitting). Using a facing ensures that the garment is finished on the inside as neatly as on the outside. Facings can also be useful along cardigan fronts, providing extra support to keep the front from stretching out of shape, covering up yarn ends from color changes, or hiding zipper tapes.

Like bindings, facings can be bulky. When they cover a cut edge, there will be three layers of fabric: the finished outer layer of the garment, the cut edge folded to the inside, and the facing covering the cut edge. When they cover an edge where there are lots of tails of yarn from color changes, there will be two layers (the outer layer of the garment and the facing), plus any bulk added by the tails. The advantage of a facing over a binding is that the bulk is moved farther away from the edge of the garment, and the facing can be worked in a thinner yarn than the rest of the project to reduce the additional bulk.

Along curved edges, like armholes and necklines, facings must be shaped to prevent the garment from puckering when the facing is sewn to it. When sewing onto the back of a knitted fabric, use matching yarn or sewing thread, being careful not to sew all the way through; the join should be invisible from the outside of the garment. When sewing a facing down over a zipper tape, use sewing thread and a sharp sewing needle, rather than a yarn or tapestry needle.

In the example shown below, a neckline was cut from an unshaped piece of knitting. The burgundy border was picked up through the fabric a short distance from the cut edge, just as for a binding. The first row of the border was purled on the wrong side, leaving a row of bumps to be used for picking up the facing. After the ribbed border was completed, the facing was picked up in pink yarn through the purled row at the base of the ribbing. Increases were worked so that the stockinette stitch facing would mimic the curve of the neckline. (These increases were 2 stitches every other row for this example of half of a front neck opening; for a complete round neck opening, about 8 stitches every other row would be needed.) The facing was bound off and then sewn down to the back of the green fabric.

In her book The New Stranded Colorwork, Mary Scott Huff uses a very clever traditional Norwegian technique for facing the cut edge of an armhole. It requires that the sleeve be knit from the bottom up with no sleeve cap shaping. At the top of the sleeve, a few rounds of reverse stockinette are worked to make a facing before binding off. The sleeve is sewn to the armhole below the section of reverse stockinette, and then the facing is sewn down on the inside to cover the cut edge of the armhole. When working the facing rounds, you must increase at the seam line so that the facing will lie smoothly against the body below the underarm.

Sewing down the facing to cover the cut edge

Facings make a very smooth finish on the right side of the fabric.

A less bulky option for covering cut edges is to sew a piece of bias seam binding, which can be purchased at fabric stores, to the inside of the garment. Because it is cut on the bias, it will stretch with the knitted fabric and go around curves. Using a sewing needle and thread, first sew down one edge, then the other. Be careful to sew through the strands of yarn on the back of the fabric so that the thread doesn’t show on the outside.

Zippers are a source of much dispute within the knitting community. The major difficulty, which cannot be overcome, is that knitted fabric stretches, but the zipper tape does not. This makes it difficult to sew the two together without stretching the knitted fabric either too much or too little. Zippers do not work well on loose, stretchy fabrics, which tend to sag on either side of the zipper, so they are best attached to firmly knit garments. If the zipper is not sewn onto the garment properly, it will look appalling and will be impossible to ignore because of its prominent position at the center front.

Unfortunately, there is little agreement on the best way to attach zippers to sweaters. Some recommend that you get a zipper longer than the opening, so that you can turn under and sew down the zipper tapes at the neck edge to make them the correct length. Others feel that the doubled sections of the zipper tape are too bulky and advocate using a zipper shorter than the opening, asserting that knitting tends to get shorter and wider over time and many washings, so the shorter tape is better in the long run as well as in the short run. This is true of some fibers (cotton sweaters tend to get shorter and wider), but not of others (garments made from alpaca and slippery fibers tend to grow longer). Some people dislike the way the zipper tape looks on the inside of the garment and prefer to cover it with a knitted facing, while others feel that the additional layer of knitting makes the sweater front much too bulky.

My own opinion is that you should suit yourself on all of these issues, and that all of the opinions expressed in the preceding paragraph will probably apply, at one time or other, to some garment or other. The most important thing is to place and attach the zipper so that the yarn at the front edge doesn’t get caught in the zipper teeth when you zip and unzip the sweater. The second most important consideration is to attach the zipper neatly and evenly so that it looks good.

Sewing on the zipper is a two-step process. First, you need to position it properly and anchor it down so that it won’t shift while you perform the second step: actually sewing it in place. Here are some hints to help you achieve that. Don’t feel that you need to do everything I suggest — some of the tips below will be more useful than others, depending on your personal inclination and the situation — but do be inspired to invent and implement other methods of your own.

You can sew the zipper in either by hand or by machine. To make the stitches less noticeable, sew through the center of the edge stitch or sew between the first and second stitch from the edge, using thread that’s as close in color to your yarn as possible. If sewing by hand, a backstitch is preferable, because it’s unlikely to break when stretched. If sewing by machine, use a stitch length that produces at least 1 stitch per row of the knitting.

On the wrong side of the fabric, whipstitch the inner edge of the zipper tapes to the back of the knitted fabric by hand, being careful to sew only partially through so that the stitches don’t show on the outside. (See Whipstitch in the appendix.)

If the zipper tapes extend beyond the ends of the opening, you may trim them or fold them under at an angle so that the ends extend away from the edge of the garment. Either way, whipstitch down the ends with a needle and thread.

After sewing is completed, remove the basting thread.

Wrong side. The zipper has been basted on with aqua thread. At left, the zipper has also been sewn down close to the edge of the knitting in orange thread using a running stitch. The excess length of the tape was folded to the inside, trimmed, and the outer edge whipstitched down in orange thread.

Right side. Even with the basting and final sewing worked in contrasting thread for clarity, the sewing is barely visible.

If you don’t like the exposed zipper tape that shows on the inside of the garment, you can enclose the zipper in a binding (see Creating a Binding to Enclose an Edge). Instead of joining the two layers of the binding when it is the width of the zipper tape, bind off the two layers separately, insert the zipper tape between them, baste carefully, and then sew in place.

You can also cover the zipper tape with a facing. You can find complete directions for doing this in “Marilyn H’s Hidden Zipper” in the Fall 2012 issue of Knitter’s Magazine. To accomplish this, she works a column of purled stitches near the front edge of the garment, then picks up along this column of stitches on the wrong side of the garment to start the facing that will enclose the zipper tape.

You can cover up the zipper teeth on the outside of the garment by picking up stitches along either edge to add a flap. If you plan to do so, be careful not to sew the zipper tape too close to the edge, which will make picking up the stitches very difficult. Choose a pattern stitch for the flap that has as little bulk as possible and doesn’t curl.

Usually the neckline of a sweater is finished off with a ribbing or other noncurling border. Much less frequently in handknits, a collar is added for a dressier look. It’s best to bind off the neck stitches and then apply the collar to the finished neck opening; the additional support this provides will help the opening retain its shape. If the neck stretches, the collar will not drape properly. The collar itself can be made separately and sewn on, or it can be picked up and worked out from the neckline.

If you decide to add a collar to a garment originally designed to have a ribbed border around the neck, you’ll need to either knit the garment pieces with a higher neck to begin with, or add the border before you attach the collar. If you don’t adjust for the missing border, the neck opening will be larger, and the collar must be shaped so that it will lie correctly (see Shaping Collars). Note that the back neck must be shaped for the collar to lie properly.

Collars in garments made from woven fabrics are stiffened using interfacing, so that they hold their shape. You could do the same to handknit collars; using fusible interfacing over the whole surface of the collar works very well to make it keep its shape. But the additional thickness may not be desirable, and the interfacing will show on the underside of the collar unless you cover it with a second layer of knitting or with a facing of woven fabric. If you prefer knitted or crocheted finishing on sweaters, as I do, then a reasonable alternative is to work the collar firmly in a noncurling pattern stitch, or to work it in two layers.

Knitted collars can be problematic because their edges and points must be perfect. Collars become the focal point of the sweater, framing the face, and any inconsistencies along the bottom or front edges are extremely noticeable. Take care to bind off at just the right tension so that the outer edge doesn’t pull in or flare, especially at the corners. You can also reinforce the edge of the collar with applied I-cord or with a crocheted edging, which will help the collar to hold its shape as well as provide a smooth, perfectly finished edge. (See applied I-cord instructions in the appendix.)

Picking up for a collar is very similar to picking up for a regular neck border except for a few very important factors. Because collars spread out from the neck opening, it’s important to pick up enough stitches for the outer edge of the collar, assuming you are making a collar that’s a straight, unshaped strip. Second, because the inside of the garment shows when the front folds back at the lapels, but the outside of the collar shows at the back of the neck if the collar rides up, it can be difficult to decide which is the “right” side to pick up on.

The weight of the sweater can be annoying to support while working the collar and can actually stretch the collar out of shape. Reduce that weight significantly by attaching the collar before you sew the sleeves into the sweater. You can also avoid this problem entirely by working the collar separately and then sewing it on.

First you’ll need to decide which is the “right” side and which is the “wrong” side.

This collar was picked up with the right side of the garment facing the knitter for half of the neckline (at left) and with the wrong side of the garment facing for the other half of the neckline (at right). With the front folded back to form lapels, the wrong side of the pickup row is exposed at left, while the right side looks nice and neat at right.

At the back of the neck with the collar up, the difference is striking. The neat right-hand side is preferable to the left-hand side, where the wrong side of the pickup row is exposed.

With the front completely closed, the difference between the two sides of the front isn’t noticeable because the collar covers up the pickup row. You can tell they are different, but one doesn’t look any better or worse than the other.

A shaped collar, like this circular collar, lies flat against the outside of the sweater. Pick up with the wrong side facing you for a shaped collar like this one, because the wrong side of the pickup row will never show.

Because a collar flares out from the neck edge, as opposed to a border, which pulls in from the neck edge, you need to pick up more stitches than you would for a border. In my experience, it’s best to pick up 1 stitch in every stitch along the horizontal cast-on or bound-off edges and 1 stitch in every row along diagonal or vertical edges. (For illustrations of how to pick up and knit stitches in each of these situations, see here.)

If the collar will be shaped to form a circle or square, proceed to shape it accordingly. If the collar will be a straight, unshaped strip, you have several options depending on the type of knitted fabric it’s made of. If it’s stretchy, no further shaping may be necessary, because it will stretch to fit around the neckline. Stretchy collars should be blocked to the correct shape so that they behave themselves when the sweater is worn. If the fabric is firm, you should increase on the first row to the number of stitches needed for the full width of the collar on its outer edge.

Knitting the collar separately and then sewing it on gives you two advantages: you don’t have to deal with supporting the weight of the entire sweater while you work, and you can knit the collar in any direction (from end to end, top to bottom, or bottom to top).

To make a collar starting from the top and working down (that is, from the neck edge and working out), follow the directions for the various collar shapes provided below, increasing to make the collar larger at the outer edge.

To make a collar in the opposite direction, from bottom to top, work the shapes, decreasing according to the guidelines for each shape, so that the upper edge is smaller than the lower edge. You can reduce the bulk where the collar is attached to the neck opening by sewing through the live stitches at the neck edge of the collar, rather than binding off and then sewing down.

To make a collar from end to end, it’s best to chart the shape on knitter’s graph paper, and then follow the chart to determine how to cast on, bind off, increase, or decrease to achieve the desired shape. You can also use short rows to make a collar flare or curve when worked from end to end.

The primary consideration for collars is that they should not curl, so avoid stockinette stitch, unless your collar will be two layers thick. To hold their shape, collars should be fairly firm, and ideally the edges should be very neat, so choose a pattern stitch that doesn’t curl and that holds its shape well. Garter stitch, worked firmly, is an excellent choice. Seed Stitch, if worked firmly, is also an option. Ribbing will also work well, especially if blocked slightly to flatten the fabric. On the other hand K1, P1 ribbing, if left completely relaxed, can masquerade nicely as stockinette stitch. If you are working a wide collar that you want to drape nicely, then intentionally make the fabric looser and softer so that it will stretch and drape to behave properly.

Corded or crocheted edges will make the edges look neat and even, help the whole collar retain its shape, and help prevent the corners from curling, something that happens frequently, even if the rest of the collar is very well behaved.

Cording along collar. This garter stitch collar has cording along both ends and the outer edge. The 3-stitch cords at the ends are worked as described in Corded Edges (chapter 2). The cording along the outer edge is worked as an I-cord Bind Off, starting with the 3 stitches from the cord already established at the edge of the knitting. To make the cord travel smoothly around the corner, 1 row of plain I-cord was worked on these 3 stitches before beginning to bind off. After all the collar stitches were bound off, the I-cord bind off was joined seamlessly to the cord at the other edge using Kitchener stitch.

Collars can be simple rectangular strips that are calmly tailored or exuberantly ruffled, can be shaped into squares or circles, and can have pointed ends. I have provided directions for the simplest of the many possible collar variations. For more in-depth discussions of tailoring collars and lapels, see Deborah Newton’s Designing Knitwear and Shirley Paden’s Knitwear Design Workshop.

As their name implies, straight collars do not actually need to be shaped in knitting. In sewn garments made from woven fabric, they have a very slight curve, so you can ease them neatly onto the neck edge of the garment; the slightly longer outer edge ensures that they lie neatly around the neck without hugging it too tightly. In knitting, which stretches, neither of these is strictly necessary, because you can block the collar to the correct shape. However, especially if you are working the collar firmly or in a non-wool fiber, it’s nice to shape it so it’s exactly right even before blocking.

Begin the collar by picking up stitches along the neck opening or casting on. If you want to shape the collar a bit, just increase a few stitches (3 or 4) evenly spaced across the row every few rows to create a slight curve. Continue until the collar is the size you want, then bind off, being careful to match the tension of your bind off to the fabric of the collar. The corded collar shown (above) was shaped by increasing just 4 stitches on every 8th row to make a very slight curve.

Shaping the points of a straight collar is your choice: leave them straight or make them pointier for emphasis. To create points, increase at both ends of the collar as you work it. The more often you increase, the more pointed the ends will be. (See photo below.)

Round collars, as the name indicates, are shaped so that they form a circle. To do this, increase 8 stitches every other round in garter stitch while working out from the neck edge. In other pattern stitches, work a gauge swatch to determine the stitches and row gauge. Figure out how long the collar must be at the neck edge and how long the outer circumference will be. Plan to increase to the required number of stitches at the outer edge over the course of the collar. This is exactly the same procedure as for decreasing to shape a curve (see Case Study #8-1).

To make a circle, rather than a geometric shape with noticeable corners, stagger the increases on each succeeding increase row so that they never line up with prior increases. This can be difficult to accomplish in many pattern stitches, but you may be able to achieve a circle by gradually moving from smaller- to larger-size needles as you work the collar. Gathering the edge of the collar attached to the neck will also help. The stitches will be held close together at the neck edge, flaring out to help produce a curve. To do this, pick up more stitches at the neck than you normally would, or increase significantly on the first row of the collar.

Shaped collar. This round collar in garter stitch is designed to lie completely flat. It was shaped by working 8 staggered increases every other row. It also takes advantage of some of the properties of knitting — that you can control how wide the knitting is by changing needle sizes and that stockinette stitch curls. The first few rows of the collar were worked in stockinette stitch, working the knit rows when the outside of the garment was facing the knitter. The stockinette stitch naturally curls to the outside, forcing the fold-over of the collar at the neck edge to be neat and hold its shape. To ensure that the collar doesn’t appear gathered where it meets the garment, the first row of the stockinette stitch section was worked on a needle two sizes smaller than the garter stitch section of the collar, the 2nd row on a needle one size larger than that, and finally on the 3rd row the switch was made to the needle size that would be used in the rest of the collar in garter stitch.

Straight collar. Note the difference in appearance between a shaped collar and a straight collar. When the garment is laid out flat, the back neck obviously sticks straight up. A shaped collar, in the same position, lies flat. The points of this collar were shaped every 4th row.

To make a square collar, pick up stitches around the neck opening, then mark four corner points. Work a double increase or a pair of symmetrical increases at each corner. Do this every other row (or round) in garter stitch. To determine the correct rate of increase in other pattern stitches, you’ll need to work a gauge swatch. Use the stitch and row gauge to work out how many rows will be in your collar and the number of stitches at the outer edge, then make a plan for how to increase over the course of the collar to end with the correct number of stitches. Remember that you’ll be increasing 2 stitches at each of the four corners, for a total of 8 stitches on every increase row/round. Notice that this is exactly the same procedure (in reverse) as for decreasing to make a border on a square neck (see here).

Square collar in garter stitch, with K-yo-K increases at each corner

Shawl collars are just wide strips of soft fabric that stretch to go comfortably around the neck. They may be set into a squared-off front neck opening, or be applied along the entire front edge of a V-necked cardigan. To add extra width to the collar at the back so it keeps the neck warm while folding over nicely, work short rows to build up that section. These may be worked immediately after picking up the stitches or immediately before binding off the outer edge, but working short rows at the beginning results in a smoother outer edge.

Shawl collar applied to a squared-off V-neck. This collar was worked straight, with no short-row shaping. As a result it is fairly low in the back where it folds over. (See schematic below, left.)

Shawl collar on a cardigan front. Short rows were worked in upper section (from the lapels up to the shoulder seams) immediately after picking up stitches. This ensures that the overlapping front edges will lie flat while the collar folds back. (See schematic below, right.)

To figure out how to work short rows to make the back neck of the shawl collar wider, you need to know how many extra rows you want to add. In this example, we’ll assume you want to make a cardigan with a shawl collar.

Note: If you’re making a shawl collar on a pullover, the first two markers should be placed at the bottom corners. After that, the short rows are worked exactly the same as for a cardigan.

See Wrap and Turn for complete instructions on working the wrap and turn and picking up the wraps.

For a collar that holds its shape better, or if you really want a stockinette stitch collar and nothing else will do, you can add a facing, which is simply a second knitted layer, shaped identically to the first, that lies underneath the collar. There are two ways to accomplish this. You can work one layer, followed by the other layer, and then sew it down, or you can work both layers at the same time, then bind them off together at the outer edge. These two methods are identical to working doubled borders or bindings, except that the collar may be shaped while the doubled borders or bindings are rarely shaped.

With the right side facing you, pick up the stitches for the collar around the neck opening. On the first row, increase 1 stitch at both ends so that, when the ends are seamed together, the collar will still be long enough to fit the neck edge. Work the underside of the collar first, shaping it if desired; end with a right-side row. On the following wrong-side row, knit across. This makes a reverse stockinette ridge that ensures a neat fold at the outer edge of the collar. Work the upper side of the collar, exactly reversing the shaping of the first layer. When completed, sew the two ends of the collar together, then fasten down the live stitches along the line where the collar meets the edge of the garment, as you would for a hem (see photo below and Hems in the appendix).

Doubled collar. The points on this collar were shaped by increasing while working the first layer, and by decreasing at the same rate while working the second layer. The collar was attached to the neckline by weaving the live stitches to the back side of the pickup row, hiding the uneven edge of the neckline for a very clean finish. The outer layer of this collar is 2 rows longer than the inner layer, so that it curves nicely over the under layer without puckering or appearing strained.

Pick up the stitches for the collar along both the inside and the outside of the neck edge just as you would for a binding. (See Creating a Binding to Enclose an Edge, for complete details on how to accomplish this.) Be sure to cast on 1 or Make 1 at the end of each needle so the collar won’t pull in at the ends.

Work your collar as for a binding, keeping it on two circular needles, and working circularly first across the one layer and then across the other on each round. Work any shaping on both the upper and lower layers so that they match. If you work the lower layer on a needle one size smaller, it may pull in just the right amount to make the upper layer lie neatly on top of it when worn. You may also work one more row on the top layer before joining.

When the collar is completed, join the two layers using either Three-Needle Bind Off or Kitchener Stitch.

Lapels form when the center front edges are folded back to form a V below the round neck opening. Shaping a V-neck removes the lapels completely, so there is nothing to fold back. For a wider lapel, the front must be shaped at the center edge to make it wider in the lapel area.

Because the inside of the garment shows when the lapel is turned back, it’s best to use a reversible pattern stitch, or to switch the right and wrong side of the pattern stitch within the V formed by the lapel area so that the right side shows when it is folded back. It’s also perfectly acceptable to use a different pattern stitch for the lapels than for the body of the garment.

Notched lapels are formed when the collar doesn’t reach all the way to the neck edge at each side.

A notched lapel, with the lapel area and collar worked in Seed Stitch. The collar was picked up with the inside of the garment facing the knitter, using “pick up and knit” on the fronts and “pick up and purl” across back neck.

So that the points don’t curl, the lapel area was worked in Seed Stitch to match the collar.

Like many embellishments that are standard on woven garments, pockets can be problematic in handknits because of the tendency of the knitted fabric to stretch. Regardless of how you construct your pockets, anything heavy placed inside them will make a sweater stretch out of shape. Despite this problem, they are still helpful for warming hands and transporting mittens.

Patch pockets are usually knitted separately and then sewn in place. This procedure is simple to understand, but can be difficult to execute neatly. To avoid the problem of sewing the pockets in place, you can pick up stitches for them instead and then knit the pocket onto the garment.

Using working yarn and three double-pointed needles, pick up and knit stitches for the two sides and the bottom of the pocket. You can fold the fabric and do this holding the working yarn on the right side, or you can leave the fabric flat and hold the working yarn behind the fabric, using a crochet hook if necessary to pull the new stitches through to the front. Along the bottom, you’ll need 1 stitch for each stitch in the width of the pocket. Along the two sides, you’ll need 1 stitch for every 2 rows in the length of the pocket. When you finish picking up the required stitches, cut the yarn, leaving a tail to weave in later.

Begin working back and forth in stockinette across the bottom stitches of the pocket. Slip the first stitch of each row purlwise. When 1 stitch remains at the end of each row, work a decrease, joining the last stitch from the pocket and the next available stitch from the side of the pocket. On the knit rows work skp; on the purl rows, work P2tog.

Picking up stitches for a patch pocket, folding the fabric, and holding the yarn on the right side. The position of the pocket was outlined in purled stitches to make picking up easier.

Picking up stitches for a patch pocket with the yarn on the wrong side

Patch pocket in progress

Using working yarn and three double-pointed needles, pick up and knit stitches for the two sides and the bottom of the pocket as described for the vertical patch pocket (above), except you’ll need to pick up the same number of stitches along both sides of the pocket as for the bottom, and spread them out so that the physical measurements of the two sides are the same as the bottom. Assuming you’ll be picking up 1 stitch in each stitch across the bottom edge, pick up for the sides at a ratio of about 5 stitches in every 7 rows of the base fabric. If this is difficult to keep track of, try 3 stitches to 4 rows instead.

Cast on stitches for the top of the pocket (the same number as you picked up for each side). You may need to cut the yarn before you cast on, depending on how you pick up the stitches and what cast on you use. Work in rounds, going down the side, across the bottom, up the other side of the picked-up stitches, and back across the cast-on edge. While you could work this pocket using Magic Loop or two circular needles (see Circular Knitting in the appendix), it is really easiest with a set of five double-pointed needles. The 90-degree angles at the corners are difficult to manage unless you change needles at each corner, and the double points allow you to do this.

Begin working circularly, working two symmetrical decreases at each corner. You could work a double decrease at each corner, but this is impractical because it requires shifting stitches between needles before working each decrease. It’s easiest to simply work one decrease at the beginning of each double-pointed needle and a second at the end of each needle. To make a flat pocket, you will need to adjust the rate of decrease to match your pattern stitch. In garter stitch, work the decreases every other round. In stockinette, work them on about 5 out of 7 rounds. For other pattern stitches, you’ll need to determine the rate of decrease, just as for a square-necked border (see here). If you’d like a pocket that pooches out a bit, then decrease more slowly. When 8 or 12 stitches remain, cut the yarn and pull it through these last stitches to secure them. If you work the pocket in stockinette, the upper edge will have a tendency to curl out. Prevent this by working the top needle in ribbing or in garter stitch on the first few rounds.

A nice variation on the mitered pocket is one with a V opening at the top. To make this, pick up stitches as for the three sides, but do not cast on any stitches for the top of the pocket. Instead of working circularly, work flat, turning at the end of each row. Work a single decrease at the top edges and two decreases at each of the two bottom corners (photo, here).

The decreases on this mitered pocket were worked 1 stitch away from the end of each needle, making the prominent cross that is its most obvious feature.

The decreases on this mitered-V pocket were worked on the right-side rows with an ssk at the beginning of each needle and a K2tog at the end of each needle. This makes the mitered corners look a little blunt. For crisper corners, reverse the position of the two decreases, using K2tog at the beginning of each needle and ssk at the end.

These pockets require no prior planning at all, which makes it possible to add them to a finished garment when you hadn’t even considered making pockets. It also lets you try on the garment to determine the correct placement for the pockets before you commit yourself. Once you’ve decided where the pocket opening should be, cut just 1 stitch at the center of the opening. This may seem traumatic, but it’s far easier than any other method.

Forethought pockets are made identically to afterthought pockets, with one important difference: you must know where you want the pocket while you’re making your sweater. When you get to this point, cut your working yarn, leaving an 8-inch tail. Knit across using a piece of waste yarn, exactly where the opening will be for the pocket. Begin using the working yarn again, leaving another 8-inch tail. When you’ve completed the piece of the garment with the pocket, pick out the waste yarn, place the live stitches on needles, and proceed exactly as described for the afterthought pocket (see here).

Forethought invisible pocket. When you use waste yarn to prepare for the opening, be sure to leave long tails (at least 8 inches) so the yarns won’t work loose, and to close up any holes later on.

Pockets can be reinforced and supported by applying an I-cord or a border after the pocket is completed. Flat borders can be worked in any of the following ways:

A border worked as a ribbing, ready to bind off

Garter stitch border attached as an edging across the top of an invisible pocket

Ruffles, cords, and other edgings can be added after the individual garment pieces are completed, or after the pieces have been put together. It’s easiest to work with the individual pieces, because they are lighter and smaller than the complete garment, but embellishments that cross seam lines must be attached after the seam has been completed. If you know ahead of time the exact location where the embellishment will be added, a series of stitches worked in reverse stockinette makes a clear anchor for attaching them.

How you pick up for the embellishment will affect how it lies against the fabric. Consistently picking up and knitting will make a ruffle, edging, or cord lie flat against the surface at its base, folding toward the knit side of the pickup row. Alternately knitting and purling as you pick up stitches will make the addition stand straight out from the fabric rather than flopping to one side.

Add a ruffle by picking up stitches along a line of reverse stockinette stitches, then increasing substantially and working until the ruffle is as deep as you like. Or make a very long strip of knitting (at least two times the width of the area where you want to attach the ruffle), bind it off, and run a piece of yarn through it, in and out between every stitch along one edge. Gather the edge of the strip along this strand of yarn so it ruffles, then sew this edge onto the garment. (For a complete discussion of the various ways to make ruffles, see How to Create a Ruffled Edge in chapter 5.)

Alternately knitting and purling while picking up stitches along a reverse stockinette ridge

Picking up in knitting makes the addition lie flat against the surface A. Alternately picking up in knitting and purling makes the addition stand up instead B.

I-cord can be added in all the ways just described for flat edgings (see here), but it can also be threaded through eyelets and other holes, like those at cable crossings, as well as knitted separately and sewn onto the fabric. (See I-cord and I-cord Bind Off in the appendix.)

Applied edgings are worked perpendicular to the fabric they are attached to. They can be simple garter stitch, any other noncurling pattern, or lace. You can add edgings to the fabric in several ways.

Edgings are sometimes too long for the edge of the fabric they are applied to. If this happens, try using a needle one or two sizes smaller to prevent the edging from flaring. Or work fewer rows of edging per stitch of the base fabric. To do this, when you reach the end of the row, knit the next 2 stitches of the base fabric together (if you’re attaching to live stitches), or skip a row when picking up the next stitch (if you’re attaching by picking up stitches). (For more photographs of edgings, see here; for more information on working applied edgings, see the appendix, and Knitting On in chapter 6.)

Lace edging worked as a bind off

A diagonal line of purled stitches was worked in the base fabric, stitches were picked up in the purled stitches, and the same lace edging as above was worked as a bind off.

The same edging worked across the cast on, picking up 1 stitch at the end of each right-side row and working it together with the last stitch of the edging

If you blocked the garment pieces before assembling them, then completely blocking the garment isn’t usually necessary when it’s finished. Do block the seams and other points like the corners of collars or front openings that could use a little shaping, and you’ll be happier with the way your garment looks and behaves. You can pin these areas to the correct shape and then steam them, or mist them with cool water and leave them to dry.

On the other hand, if you didn’t block the pieces or there are larger issues that blocking can address (for example, the two fronts aren’t quite the same length), then blocking the complete garment is an excellent idea. My preference is to wash the garment as I would normally launder it. At the very least you should soak it in warm water so that the fibers absorb plenty of moisture. Squeeze it out, roll it in a towel to remove the excess moisture so it’s not dripping wet, then lay it out flat to dry, shaping it to exactly the size you want. You may need to pin sections in place or use blocking wires to keep select areas under tension so they look their best. For complete details on blocking, see here.

For the most part, the best way to wash any handknit garment is to soak it in warm water with mild detergent, squeeze gently, and soak in clear water to rinse. Remove the excess moisture by rolling in a towel, then lay the garment out flat to dry, shaping as described in Blocking Knitted Pieces in chapter 7. Sweater-drying racks made of nylon net let air circulate so the garment will dry more quickly while laid out flat to prevent stretching. Many of these are stackable so you can wash several sweaters at a time and dry them in a small space.

Handknit garments should not be hung, unless you want them to stretch. Instead, fold them neatly and store away from sunlight. To avoid moth damage, wash them to ensure that they’re clean before storing and make sure they are completely dry. If you have problems with moths, silverfish, or other insects that eat fiber, seal your garments up in plastic bags and check them frequently for problems. If you store your garments in plastic, it’s vital that they be completely dry, stored out of sunlight, and in an area that doesn’t experience extreme changes in temperature. This is necessary to ensure that condensation doesn’t form on the inside of the bag, causing mildew and possibly felting wool or other animal fibers.

I wish I could guarantee that, if you take all of the tips and advice in this book to heart and apply them to your project, you’ll love the end results. Unfortunately, I can’t in all honesty do that. The fact is, you won’t see or try on the finished garment until it’s, well, finished. Being alert, analyzing your progress, and assessing the fit as you work will help you find or prevent numerous problems, but there’s still the possibility that even if everything is exactly what you intended, you won’t be happy with the end result.

On the one hand, this will be frustrating. You should justly mourn your failed project (assuming it really is irredeemable).

On the other hand, think of all the things you learned from knitting it so intentionally — from casting on the first swatch to sewing in the last end, your attention to selecting the best structure, texture, color, embellishment, fit, and the best techniques to achieve the end product has elevated the craft of knitting to the level of art.

In the course of the project, you’ve probably been excited, happy, frustrated, challenged, analytical, and creative. You’ve entertained yourself (and perhaps others) in the pursuit of the perfect garment and this pastime has come at a very low cost — just the price of the yarn and the pattern, especially when compared to the expense of a dinner out, a movie, or going to the theater, a concert, or a sporting event, which are much more fleeting amusements. If worst comes to worst and you decide to cut your losses, unravel the whole thing, and start over, or to make something else entirely, think of it as getting more entertainment for your yarn dollar. There’s no reason why you shouldn’t enjoy the whole process once again.

What to do? First, try to figure out what, exactly, is wrong. Put the sweater on yourself or on the person it was intended for and assess the problem with brutal honesty. Is it ugly all over? Does it hang wrong? Is the fit too tight or too loose in places? Are the seams the focus because they’re too tight? Are the borders messy? Does one section look noticeably different (messy, tighter, looser, lighter) than the others?

Perfection is an abstract and unattainable ideal. Instead, set your own standard for excellence, pursue it, and find satisfaction in its achievement. For more information on the Cape Point Short Sleeved Top, visit the author’s website, www.maggiesrags.com

If the sweater fits and all the finishing looks good, but you don’t like the way it looks, you do have some practical options for improvement.

Managing mistakes. If there are mistakes in the pattern stitch or dropped stitches, see Fixing Mistakes in chapter 6 for approaches to correcting them. Mistakes of this sort can also be hidden or camouflaged by adding a patch pocket, some embroidery, or an embellishment like a bead or a braid on top of the offending spot. Of course, you’ll also need to add similar embellishments in other places to make it look intentional.

Coping with color. If the color of the yarn (or the combination of colors in a variegated yarn) gives you visual indigestion, then consider dyeing the garment to tone things down. There was a time when I would have been terrified of the very idea of dyeing my garments, but dyes for both animal and plant fibers are now widely available. Make sure you choose dye that’s appropriate for the type of fiber and that you get enough to dye the weight of the yarn. Keep color theory in mind — yellow and blue mix to make green, red and blue to make purple, and yellow and red to make orange — and this applies when you add dye to the color that’s already on the yarn.

Test your dye on a little of the leftover yarn in all the colors or on your swatch before you commit to dyeing the whole sweater. Note that you don’t have to saturate the color — subtle overdyeing can change its appearance significantly and if you decide you want more color, you can always dye it again. Remember that you can make it darker, but not lighter. Follow the directions that come with the dye carefully and treat your garment carefully so that it doesn’t shrink or felt. Acid dyes used on animal fibers can usually be applied while cold and then heat-set, making it less likely that shrinkage or felting will occur.

Variations in the yarn. If one section of the garment looks different from the others, try to figure out why. Is the color slightly different (perhaps a ball of yarn from a different dye lot)? Is it a bit looser or tighter (perhaps you used different needles or were more relaxed while knitting)? Did you perhaps work the pattern stitch differently in this section?