Now that you’ve made the major decisions — yarn, needles, pattern — you’re ready to jump right in and get started, right? Probably not.

This is the moment to consider whether there are any other decisions you need to make before you begin. Is there anything you want to change about the sweater? Even if you plan to follow the pattern instructions without any modifications, is there something that worries you about any of the techniques, shaping, or finishing?

Taking charge now, thinking ahead to plan the best approach for your project and the best way to handle the finishing will make the whole process of knitting and completing the garment go more smoothly. You’ll be able to work more efficiently, there’ll be less chance of major problems that could force you to rip out, and finishing will be much easier if you plan ahead based on the suggestions in this chapter. You’ll be glad you did!

Most patterns instruct you to begin with the back of the garment, then proceed with the front, the sleeves, seaming, and borders. There are, however, reasons why you might not want to do things in this order. Let’s say that you ignored all of the excellent advice in chapter 1 about working gauge swatches and want to jump right in. In this case, it’s much better to begin with a sleeve than with the back of the sweater. The sleeve will be narrower in width, so it will grow more quickly. When you’ve worked a few inches, stop and measure to ensure that you really are working at the desired gauge. If not, unravel and switch needle sizes — you’ll have a lot less invested in the project after a few inches of a sleeve than after a few inches of the back. If you’re working your sweater circularly, there’s even more of a difference, because working a few inches of the back plus the front is double the work of starting just the back. In the next few pages you’ll find several different approaches to garment construction.

The back is usually worked before the front because the shaping of the back is usually simpler: the back neck begins closer to the shoulders, so the underarm shaping has usually been finished before you are required to embark on the neck shaping. This gives you a chance to warm up. Having successfully completed the back, it’s assumed you’re ready for the additional challenge of shaping the front neck, which may occur at the same time as the armhole shaping. Another assumption is that you’re more likely to make mistakes on the first piece of the sweater, or to have second thoughts, and you can then use your experience to improve the front. The logic is that the front, which is more noticeable, will look better than the back. But, if you know yourself to be the kind of knitter who is interested and excited at the beginning of a project, and becomes bored with the repetition of maintaining a pattern row after row, garment piece after garment piece, this may not work to your advantage. If you do your best work early in a project and then rush carelessly to the end, you might want to make the front first. Except for considerations like these, with any garment knit in pieces and then sewn together, it really doesn’t matter in what order you construct the pieces.

Except (isn’t there always an “except”?) . . . if you want to ensure that the sleeves are the perfect length, it’s really best to save them for last. How, you ask, can you make the sleeve both first (in place of a gauge swatch) and last? Easy, start the sleeve and don’t work any farther than the underarm, then leave it on a spare needle or a piece of yarn until you’re ready to check the length.

The order of construction that I prefer, to ensure that the sleeves really are the right length, is to make the back and front (it doesn’t matter which comes first), block these pieces, then join the shoulders, and add the neck border before completing the sleeves. Blocking is necessary with fabrics that will be stretched to size during the process (made from fabrics that are ribbed, cabled, lace, or in any other pattern stitch that should be flattened for best effect). Blocking is also the best practice in plain stockinette stitch and other pattern stitches, because it will help to uncurl and neaten the edges, which makes seaming easier, and will allow you to verify the finished dimensions. Try the garment on. Make sure the neck fits the way you like it. If not, fix it before moving on. (See Getting Neck Borders Right.)

If it’s a drop-shoulder sweater, the edge of the armhole will fall some distance down the arm from the shoulder, so the sleeve must be shorter than you might expect to fit properly. Take a look at the schematics showing different armhole and sleeve styles for the same size sweater (Recognizing Fit) to see just how much the sleeve length can vary between a capped sleeve and a drop-shoulder sleeve. Try on the partially finished sweater. Measure from the edge of the armhole at the top of the shoulder down the arm with the elbow slightly bent, to the point where the sleeve should end. That’s the length that the sleeve must be in order to fit well.

Sometimes the weight of the sleeve once attached will stretch the shoulder seam out, so plan for this by testing the shoulder to see how much it stretches and deduct a little bit from the sleeve measurements if necessary. Binding off the shoulders and sewing them together or using Three-Needle Bind Off to join them will usually provide enough support to minimize stretching. (For more on stabilizing shoulders that may stretch, see Seams, here.)

If it’s a fitted sweater, with a shaped armhole and sleeve cap, the critical length is from the underarm to the cuff. To be able to measure this accurately, it’s best to baste the side seams of the sweater, put it on, and then measure from the top of the side seam at the underarm along the inside of the arm to the cuff. Make sure that your sleeve is this length to the underarm. Because the height of the sleeve cap will vary depending on the width of the sleeve and the shape of the armhole, it is not a good indicator.

Finish the first sleeve, baste or pin it in place (with safety pins) and try on the one-armed sweater. Basting is the only way to get a good feel for the fit of a shaped armhole and sleeve cap, but you can get away with pinning on a drop-shoulder design. A smooth, contrasting basting yarn will be easy to remove; avoid a fuzzy yarn that may leave noticeable residue. If the sleeve fits, make a second just like the first. If it doesn’t fit, figure out what needs to change, unravel and revise the top of the sleeve, and try it on again. See the section on designing a sleeve cap under Adjustments for a Round Armhole for making adjustments to sleeve caps. Make a note of what you did so that you can make the second sleeve identical to the first once you get it exactly right.

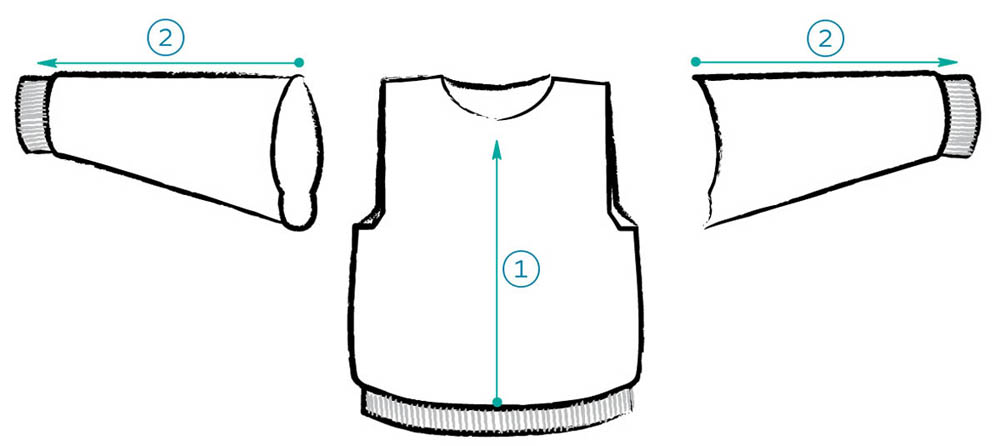

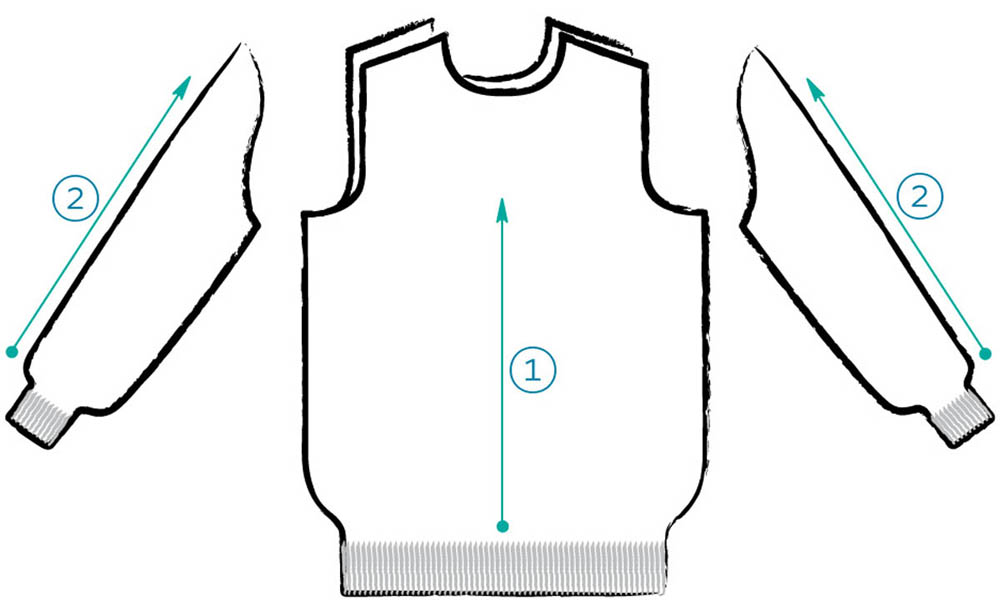

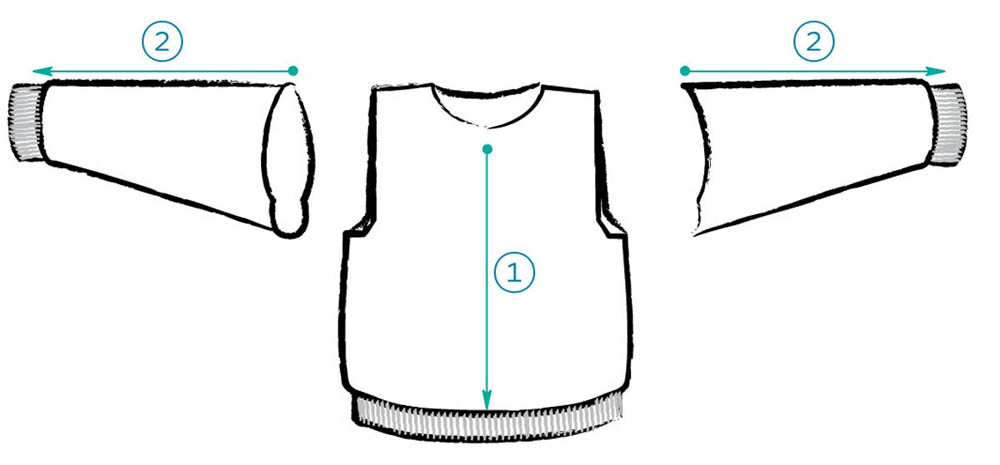

Conventional order of construction: 1 back, 2 front, 3 sleeves, 4 neck border

My preferred order of construction: 1 back, 2 front, 3 neck border, 4 sleeves

So far I’ve focused on bottom-up construction of sweaters made from separate pieces and then seamed, but there are plenty of other ways to make a sweater. First let’s look at seamless sweaters worked from the bottom up.

Pullover vest. Knit the body circularly up to the underarms, the front and back separately from that point to the shoulder, and then join the shoulders using three-needle bind off.

Drop-shoulder pullover. Make the body the same as the pullover vest, but without underarm shaping. Sleeves can be knit circularly from the bottom up and then sewn into the armhole, or knit down from stitches picked up around the armhole, thus avoiding seams. Working the sleeves from the top down makes it easy to ensure they’re the correct length.

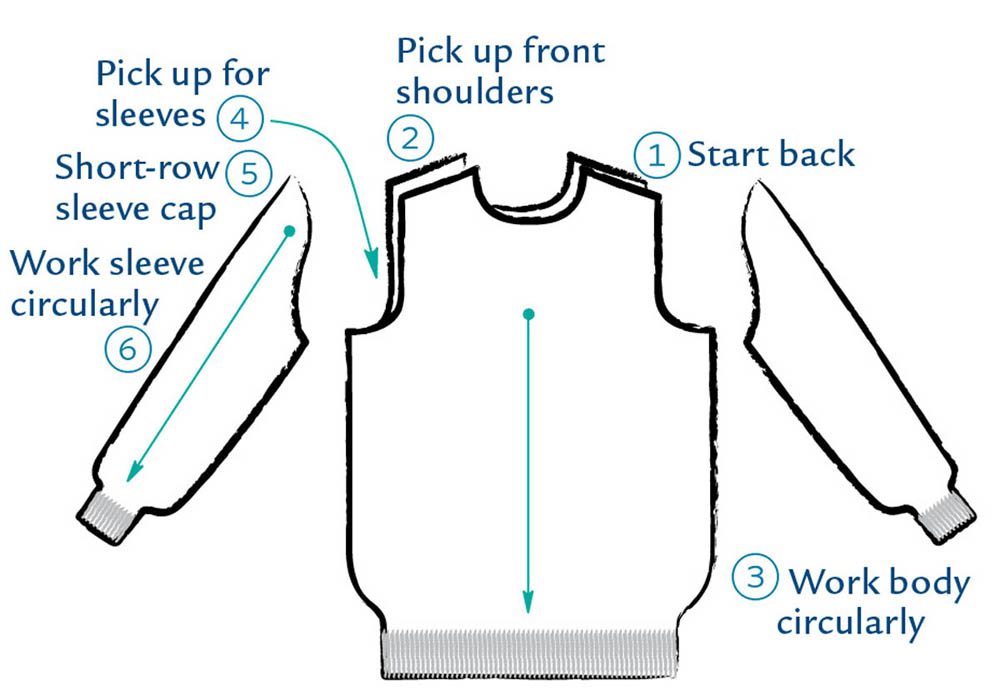

Tailored pullover. A fitted sweater with set-in sleeves and shoulder shaping can also be knit circularly. Make the body as described for the drop-shoulder pullover. Work the sleeves circularly from the bottom up until you reach the underarm, then flat through the cap, and sew them into the armholes. Alternatively, using short-row shaping for the cap, set-in sleeves can be picked up and worked down from the armholes. (See Case Study #3-3.)

Cardigan vests and sweaters. Work the body flat in one piece to the underarms, then complete the armholes, shoulders, neck, and sleeves as described for the pullover versions above.

Circular-yoked pullover. Work the front, back, and both sleeves circularly to the underarm, then assemble them all on one needle to work a circular yoke, decreasing as you approach the neck opening.

Raglan-sleeved pullover. Work just as for a circular yoke above, but line the decreases up at four corner points to define the sleeves within the yoke area.

Raglan or circular-yoked cardigans. Work flat in one piece up to the underarms, then add sleeves and shape the yoke as described for the circular and raglan-sleeved pullovers, but work the yoke area flat, leaving the center front open.

Identical to bottom-up construction, except that you begin each piece at the top and work down to the bottom, this is advantageous if you are working a pattern stitch that you like better when seen upside down. It also allows you to fit the neckline, armholes, and sleeve length as you work. In this case, I give the same advice as I offer above for working bottom to top in separate pieces: complete the back and the front, join them at the shoulders, and complete the neck border before working the sleeves. When working the sleeves from the top town, stop at the underarm (assuming you’ve got shaped armholes and a sleeve cap) and evaluate whether the sleeve cap will fit properly, then continue working down the sleeve until it’s just the right length.

Top-down flat knitting.. Order of construction, 1 back; 2 front; 3 sleeves

Follow the same process as bottom up, except in reverse. What’s important is that the distance from the neckline or shoulder to the underarm join be long enough that it’s comfortable to wear. After you divorce the sleeves from the body, continue to work each of the sections until they are the right length. Because it’s easy to try on the garment and check the length, many knitters advocate this as the best method for making sweaters that fit well. Versions of all of the following garments can easily be made with open fronts. Instead of joining into a round to work circularly, leave the knitting open at the center front and work back and forth, making the fronts and back all in one piece.

Pullover vest. Work the front and back separately down to the underarms. One of them can be made first, then stitches for the other can be picked up along the shoulder instead of casting on, to avoid having to sew a seam. Use a very firm cast on at the shoulders to prevent the shoulder seam from stretching and spoiling the fit. After you reach the underarm, begin working the whole body (back and front) circularly.

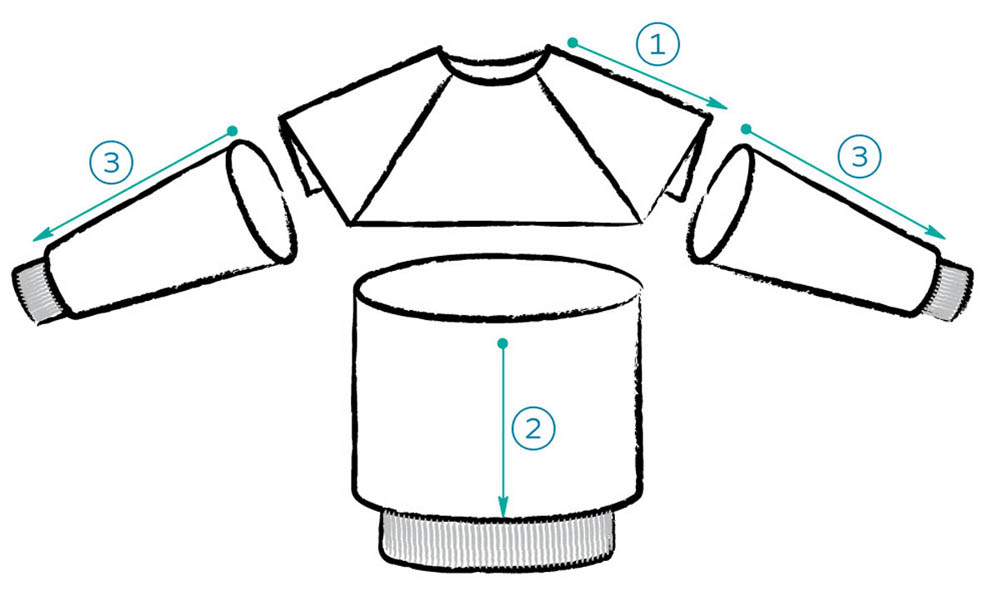

Drop-shoulder pullover. Work the body as described for a vest above. Pick up stitches for the sleeves around the armholes and work them down as well.

Tailored pullover. To make the sloped shoulders, cast on small groups of stitches until the shoulder is wide enough. You’ll have to sew the shoulder seams later on. For true seamless construction, cast on all the stitches for the shoulder (using a firm cast on so that the shoulder won’t stretch and spoil the fit, then work short-row shaping as described in Adding Shoulder Shaping. When starting the opposite piece, pick up along the shoulder cast on and work another set of short rows, reversing the shaping. Pick up stitches for the sleeves around the armhole, then work short rows to create a sleeve cap as described in Case Study #3-3.

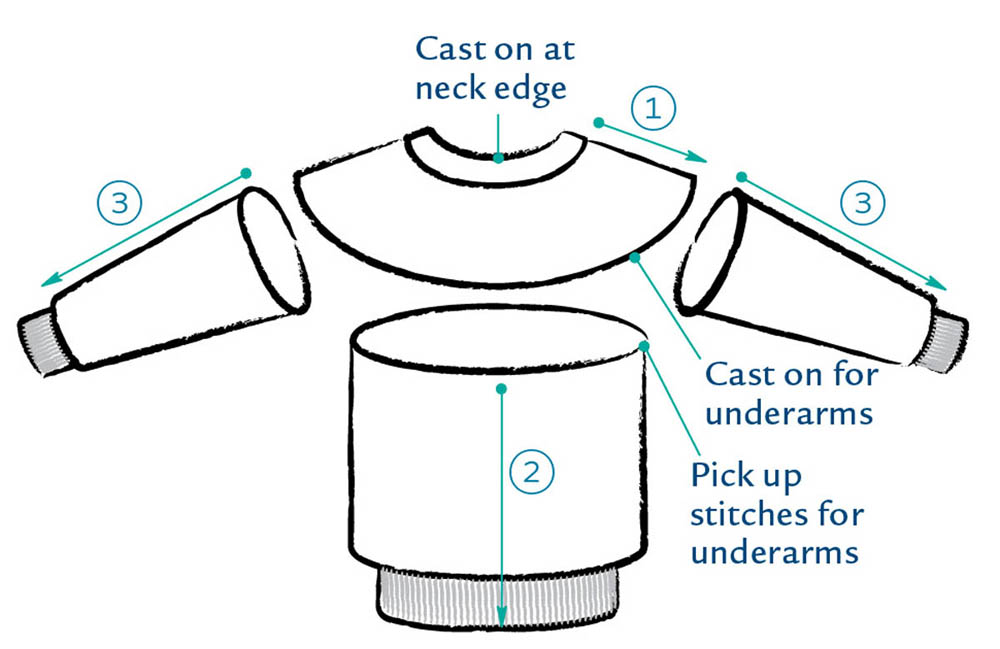

Circular-yoked pullover. Cast on at the neck edge, work the border, then increase to make a circular yoke. Divide the stitches, setting aside the sleeve stitches, cast on for the underarms at both sides of the body, and work the body (front and back) circularly down to the bottom. Work the sleeves down, picking up stitches across the underarms of the body.

Raglan-sleeved pullover. For an unshaped neckline, make this identical to a circular yoke, but place the increases at four points to define the sleeves. To make a shaped raglan neckline, begin by working flat on just the stitches for the back neck and shoulders. You’ll increase at four points to define the sleeves and also will increase and/or cast on to shape the front neck opening. When the neck opening is complete, begin working circularly.

Occasionally pattern writers specify which cast on to use, but it’s far more likely that your pattern will simply instruct you to “cast on.” If you’re like most knitters, there’s one cast on you use all the time, never considering whether it’s the best one for the job. I’ll put my professional standing on the line and say that, if you’re only going to learn and use one cast on, the best is the long-tail cast on. It is neat, stretchy but not loose, and, once learned, you can work it faster than any other cast on. But even this versatile cast on won’t be a practical option in some situations.

It’s really best to be familiar with several cast ons and to choose among them depending on how the cast on needs to behave, as well as how it looks. You’ll find instructions for each of the cast ons mentioned below in the appendix.

The most important consideration for a cast on is whether it’s elastic or firm. For example, at the neckline of a pullover, it will need to stretch enough to go over the head but be supportive enough to prevent the neckline from stretching out of shape. At the cuff of a sweater, it will need to stretch enough to pass easily over the hand but have enough memory to return neatly to its original length. If the cast on is at a rolled edge or the edge of a ruffle, it needs to be very stretchy or the rolled edge won’t roll and the ruffle won’t ruffle to its full potential.

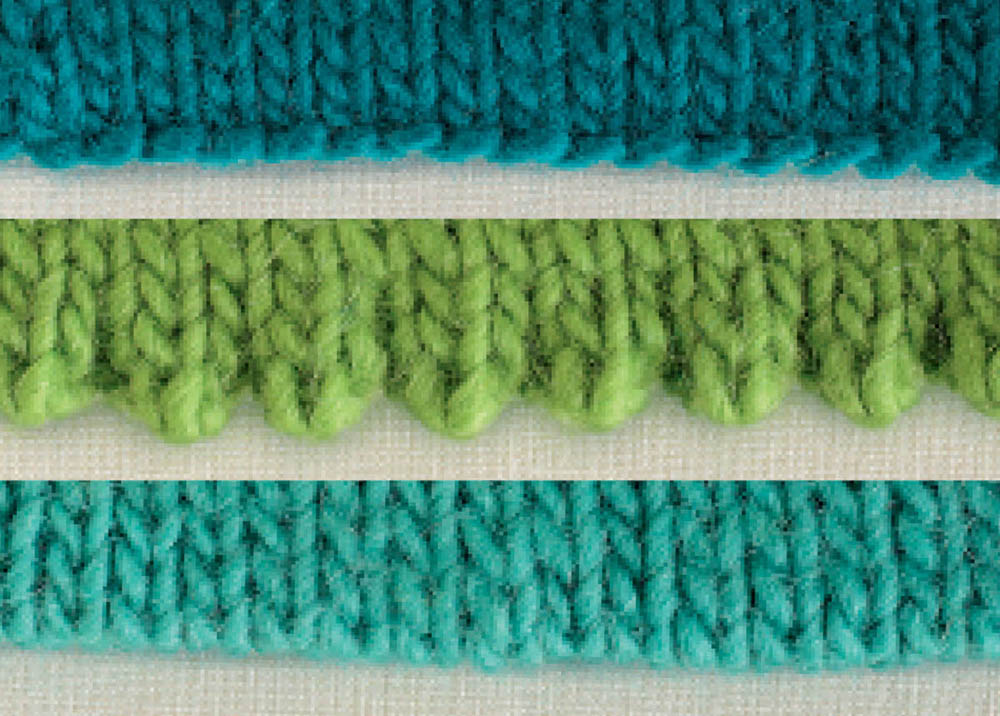

Very stretchy cast ons include knitted, half-hitch, lace, and tubular. Moderately stretchy cast ons include long-tail, Channel Islands, and ribbed cable. Supportive casts ons stretch just a little, and then no farther. The cable cast on is a good supportive cast on. (See photographs below for examples of each of these.)

Knitted cast on, if not worked very firmly, tends to look loose and loopy, but this is an advantage if you want a stretchy edge.

Lace cast on is formed by working a yarnover between each stitch in a cabled cast on. It stretches magnificently, with decorative loops that can stand alone, be used to join to another piece of knitting, or support other ornaments like beads or fringes.

Half-hitch cast on. The tension of the half-hitch cast on is easy to adjust by simply spacing the stitches out more or placing them closer together on the needle. It can be difficult to work into on the first row, however, so is best reserved for short cast ons where you want a minimum of bulk, like the underarms of sweaters when working top down.

Tubular cast on makes a very stretchy edge that integrates perfectly with K1, P1 ribbing. Tubular knitting can be worked following the cast on to make a casing for elastic or a drawstring.

Long-tail cast on is the best all-around cast on. It looks neat when relaxed but stretches well under tension. You can control how tight it is by how tightly you tension the tail and how closely you space the stitches on the needle when working it.

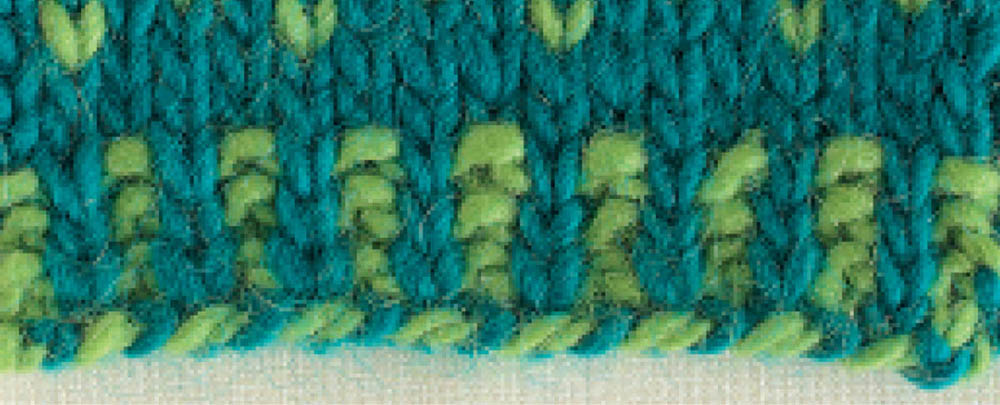

Channel Islands cast on is a little more complicated to learn and execute than the others shown here. It can take a little practice to be able to work it with consistent tension, but it’s worth the effort. The double strand across the bottom means this cast on will wear well, while the tiny bumps every other stitch make a lovely embellishment. It integrates extremely well with K1, P1 ribbing, but looks good with almost any pattern stitch.

Ribbed cable cast on also makes a doubled strand across the edge of the fabric that will wear well over time, transitions perfectly to K1, P1 ribbing, looks almost identical on both the front and back, and stretches well.

Cable cast on is a variation of the knitted cast on that produces a noticeable ropelike edge. Its ability to stretch is limited, making it perfect for an edge that you don’t want to stretch very much. You can work the stitches farther apart to make it stretch more.

Long-tail cast on made with thumb strand doubled

Cast ons under tension, from top to bottom: tubular on K1, P1, Channel Islands on K1, P1, half hitch on garter, lace on faggoting rib

Will the cast-on edge be subject to wear? The bottom back edge and the cuffs of sweaters are subjected to significant abrasion and abuse, especially in children’s garments, so you’ll need a cast on that will stand up to wear and tear. On the other hand, the delicate edge of a lace shawl to be worn only on formal occasions can be gossamer thin, in keeping with its intended use. In a situation where high durability is desirable, choose the cable cast on or work the long-tail cast on with the thumb strand doubled.

Will you be able to see the cast on once the garment is finished? If the edge will be hidden in a seam, behind the picked-up edge of a border, or rolled up in stockinette stitch, it doesn’t matter how it looks. If, on the other hand, the cast on will be visible every time the garment is worn, think about how it will look. Will it integrate agreeably with the adjacent ribbing or pattern stitch? Some cast ons produce a very definite ridge across the bottom of the fabric, some produce a twisted, ropelike edge, while others look ribbed or purled.

If the edge will normally be relaxed, then the relaxed tension of the cast on should match the tension of the fabric it’s attached to. A fabric where the stitches are wide in proportion to their height, like garter stitch or open lace, may require a different or looser cast on than a fabric like ribbing or cables where the stitches are proportionately narrower. If the edge will normally be stretched when the garment is in use, make sure the cast on is still pleasing when stretched.

Hems, from top to bottom: folded, picot, rolled

Long-tail cast on without increases at base of cables

Long-tail cast on with increases at base of cables

To add an embellishment or special effect at the beginning of your knitting, choose a decorative cast on, or work an edging as long as the width of the desired cast on and then pick up the required number of stitches along the side of the edging. Decorative treatments include Channel Islands cast on (for a picot edge), casting on additional stitches to make a ruffle, lace cast on, multicolor cast ons like the two-color versions of the long-tail and cable cast ons, and hems. Edgings can be as simple as a strip of garter stitch or an I-cord, or they can be a complex lace pattern. For a ruffled edging, make a strip of edging longer than required, pick up stitches along it, then decrease to the correct number of stitches.

Channel Islands with garter stitch (right side)

Channel Islands with garter stitch (wrong side)

Ruffle at cast on

Long-tail cast on using multiple strands in different colors

Long-tail cast on with one color on thumb and another color on finger

Long-tail cast on alternating colors

Cable cast on alternating colors

Stockinette picked up along garter stitch edging

Stockinette picked up along I-cord edging

Picked up along lace edging to make a ruffle (left) and without a ruffle (right).

Casting on at the edge of your work to shape a neckline or armhole when working from the top down, over an opening like a buttonhole, or when starting a steek requires a single-strand cast on. See Casting Onto Work in Progress, for more information on choosing the best cast ons for these situations.

There are situations where you’ll want to begin your work in the middle, for example, if you plan to add the borders later. In these cases you’ll need to use a provisional cast on, which is simply a cast on worked in contrasting waste yarn that is easy to remove. Once removed, the bottoms of the original stitches are placed on a needle, and you can work seamlessly in the opposite direction.

Using a strong, smooth, slippery waste yarn (such as mercerized crochet cotton) will make removal easier and ensures that no contrast-color residue is left on your project. Several Provisional Cast Ons are explained in the appendix. Choose whichever one you feel most comfortable with.

As an alternative to using a removable cast on, you can simply cast on and knit a few rows in contrasting yarn, cut it, and begin working with the yarn for your project. When you are ready to remove the waste yarn, take a pair of sharp scissors and cut across the top row of the waste yarn. Slip a needle into the first row of stitches in the project yarn and pick out any remaining snips of the waste yarn.

If cutting your knitting (even if it is waste yarn) makes you nervous, you can steal a trick from machine knitters and use ravel cord. This is a very strong, very smooth cord that can be removed just by pulling on the end of it. If you don’t have access to machine knitting supplies, you can substitute a soft nylon macramé cord or dental floss. Cast on and work just one row in waste yarn. Change to your ravel cord and work one row. Change to your project yarn and begin working the garment. Because the ravel cord is very slippery, you may want to tie the ends to the waste yarn and project yarn. (Be sure to make knots you can easily untie.) When it comes time to remove the cast on, check that both ends of the ravel cord are untied and aren’t twisted back on themselves through the stitches at the ends of the row. Pull on the ravel cord until all the slack is taken out of it and the row becomes very tight. Continue pulling and it will slide out of the row, separating the stitches in waste yarn from those in the project yarn. Slip a needle into the first row of stitches in the project yarn. You can also slip the needle in before removing the ravel cord, but this can make it more difficult to remove the cord; placing the stitches on a very thin needle or the cable of a circular needle will make removing the cord easier.

If there will be a seam starting from the corner at the cast on, be sure to leave a long tail for sewing it up later. You’ll have fewer ends to weave in that way. Make the tail into a butterfly to keep it out of the way. Secure the butterfly to the fabric with a safety pin to keep it from pulling loose.

How you join the beginning and end of round when working circularly depends on your personal preferences. The appendix provides instructions for three different methods of joining. It’s good to be familiar with all three, because any one may be preferable depending on the project you’re working on. If the beginning/end of round at the edge won’t show (for example, when it’s hidden in a seam, behind a border, or in a rolled edge), then choose whichever is most comfortable for you to work. If the cast on will be visible, experiment to see which one looks the best and is the most practical when beginning your project.

If you are never happy with your cast on, consider adding the borders later. Start with a provisional cast on, casting on the number of stitches needed after the border, and work the rest of the piece. Remove the cast on, place the stitches on the size needle needed for the border, work one row or round, increasing or decreasing to the correct number of stitches, and finally work the border and bind off. The result is no cast-on edge at all — only matching bound-off edges at top and bottom.

Most knitting designers have taken care of placing any pattern stitches so that they look good on the garment. But, if you’re making fitting adjustments, changing the pattern stitch, or you want to add your own large motif, consider where to place it on the garment before you begin. The larger the motif, the more care you’ll have to take. Avoid putting prominent sections of the motif at the points of the bust, or centered on a prominent stomach or bum! Also avoid having the edges of the motif cut off by armhole or neck shaping. If it doesn’t fit in the space available, it’s best to downsize the motif to make it fit. Center large motifs horizontally on the front, back, and sleeves. Consider where the pattern will fall at the shoulders and arrange it so that the shoulder seams cut across the motifs at a pleasing point. The easiest way to plan the placement is to create a chart for the actual shape of each garment piece, in rows and stitches, then chart the pattern on it. Remember that the outer edges of motifs that extend all the way to the side seams will be obscured when the sweater wraps around the body.

If the major motif has an odd number of stitches (as is usually the case with stranded knitting), you’ll need an odd number of stitches in each section of the garment in order to center it. Plan the front and back so that the shoulder seams fall either above a major section of the pattern or at the center of a motif; then the pattern will look continuous across the shoulder from front to back. Plan the sleeves so that the top of the sleeve and the bottom where it meets the cuff fall between major sections of the stranded pattern.

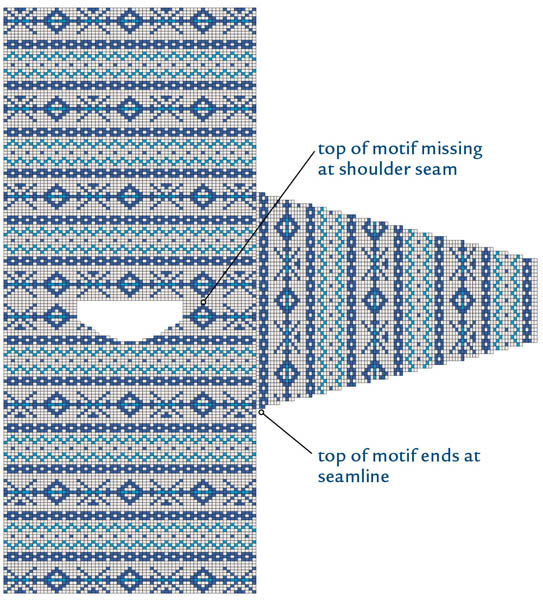

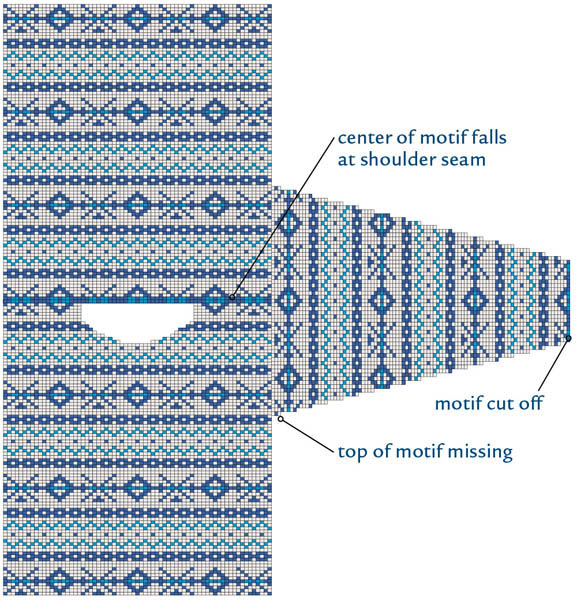

For example, in the top chart for the stranded pattern opposite, notice that the shoulder seam falls at the top of two major horizontal patterns, but, because the darker narrow pattern that divides them is missing, the overall pattern is noticeably interrupted at this point. The sleeve layout is more pleasing, with the dark chain pattern falling at both top and bottom.

In the version of the same chart shown below it, slight changes in the way the pattern is laid out on the garment result in major differences. The shoulder seam of this version is much more pleasing because it falls at the center of a motif, but the sleeve is less satisfying because the dark chain motif that defined its top and bottom edges in the other version is missing.

Compare the differences between shoulder details and top-of-sleeve details in these two illustrations.

If the major motif has an even number of stitches (as is frequently the case for cabled patterns), you’ll need an even number of stitches for each section of the garment in order to center it. Centering the major pattern elements horizontally is simplified if a small pattern, such as Seed Stitch or repeated 2-stitch cables, is used at the sides of the front, back, and sleeves.

With large cabled motifs, it’s important to plan the placement vertically as well, so that the cabled pattern integrates nicely with the neck opening and any other shaping. Cables should also end symmetrically at the shoulder seam, with the final cable crossing the same distance below the seam on both front and back. Ideally, the seam should fall at the halfway point between crossings so that the cabled pattern appears almost continuous from front to back.

Planning cables. Care was taken to place the bottom of the neck opening at a point in the complex cable design where it does not cut across any major cable crossing and where the outer ribs of the cables frame the opening (first photo). Notice how the neck shaping integrates with the Gull-Wing Cables on either side. Half of each cable disappears, making it easy to continue the pattern on the other half all the way to the shoulder seam.

In the second photo, you can see that the shoulder seams were planned so that the Gull-Wing Cables mirror each other perfectly.

Once you’ve selected your pattern and yarn, taken the time to test-drive your needles by working a swatch, checked for shrinkage (or growth) and planned for it, you’re going to want to jump right in and start your garment. Don’t. Exercise your patience once again and do just a little more planning. Before you start, think about what will happen when you finish. Unless you’re making a seamless circular garment, you’re going to need to sew the thing together. Decisions you make before you work the garment pieces will have major impacts on how easy it is to join the pieces and pick up borders, and how good the finishing details look when you’re done.

First let’s talk a little bit about bottom borders, since most sweaters start at the bottom edge with some sort of noncurling border. It can be difficult to make the borders in the correct proportion to the body of a garment. The basic rule of thumb for ribbed borders attached to stockinette stitch is to make the borders with needles two sizes smaller and with 10 percent fewer stitches than the body. This works just fine if you happen to get the same gauge as the designer on the borders, if you’re working with a wool or wool-blend yarn that has good memory so the ribbing pulls in the proper amount, and if the rest of your garment is worked in stockinette stitch.

This border was worked circularly, while the garment is seamed above the border.

It also requires forethought and excellent finishing skills to make the borders of garments look good where seams are sewn. With a little care in centering ribbing, however, you can noticeably improve the appearance of seamed borders. Many knitters (myself included) have messy-looking ribbing because of inconsistencies in tension between knit stitches and purl stitches. Both of these problems can be mitigated by making the borders circularly, even if the rest of the garment is worked in flat pieces as in the photo bottom left.

Before you start your garment, test and evaluate the borders on a swatch as described in Swatching to Refine the Details.

The convention for well-behaved borders (10 percent fewer stitches and needles two sizes smaller) doesn’t always work. All knitters are not alike: some knitters work ribbing that is much looser or much tighter than the original designer expected, and they must adjust their needle size accordingly to get good results. You’ll find out whether this applies to you when you swatch; you can adjust for it automatically on future garments. All yarns and fibers are not alike: the 10 percent and two-sizes-smaller rule usually applies for stretchy wool yarns, but not for yarns with no elasticity or fibers that are not wool. You may need to go as much as four needle sizes smaller and 15 percent fewer stitches when working with inelastic yarns that don’t return to the original width after stretching the border. (See Fiber Content and the Finished Fabric.)

Why are borders worked on fewer stitches than the body of the garment? Borders are at the edges of the garment and are frequently under tension either from the weight of the garment (neck and armhole borders), when we move or sit down (bottom borders), and when we push our sleeves up (sleeve borders). All of these borders are stretched whenever we put the garment on or take it off. They tend, therefore, to get stretched in width. Making them narrower to begin with means that when they do stretch out of shape, they are still the same width or narrower than the body of the garment, which keeps them looking neat. Stockinette stitch naturally curls to the outside at the top and the bottom, so making the bottom borders slightly narrower than the body or sleeve they are attached to also prevents them from flipping to the outside of a garment whose main fabric is stockinette stitch.

The traditional ribbed border that’s narrower than the body of the garment may not be what you want aesthetically, or it may simply not be practical with the yarn and fiber you’ve selected. In this case, you might want to make a bottom border that doesn’t curl, but one that also doesn’t pull in like a standard ribbing. You can substitute a garter stitch or Seed Stitch border, or a decorative edging. Be sure to check the gauge of these and make them exactly the same width or a tiny bit narrower than the section of the garment they are attached to, so they don’t flare or flip up annoyingly.

For more about designing the best borders and about shaped borders for necklines and armholes, as well as the bottom borders I’ve discussed here, see Changing the Borders and The Special Challenge of Shaped Borders.

Getting ribbing right. Border worked on 10 percent fewer stitches and needles two sizes smaller A; border worked on 10 percent fewer stitches and same size needles B; border worked on same number of stitches and same size needles C. A is what you want.

Dealing with inelastic yarns. Linen yarn in a K1, P1 border with 10 percent fewer stitches and needles four sizes smaller A; same yarn in a K1, P1 border with 10 percent fewer stitches worked on needles two sizes smaller B.

K3, P3 ribbing in linen yarn is very elastic.

K1-tbl, P1 ribbing in linen yarn makes very neat ribs.

Seed Stitch, for a nonribbed, noncurling border

One of my pet peeves in knitting patterns is being told to begin by casting on an even number of stitches and then work in K1, P1 ribbing for the bottom border. When you go back to sew the seams, whether it’s a sleeve seam or a side seam joining the front to the back, there’s no way to make the ribbing look good at the seam. The same thing happens when you cast on a multiple of 4 stitches and work in K2, P2 ribbing.

This is because one side of the ribbing ends in a knit rib and the other ends in a purl rib. To make a neat seam, the ribbing needs to be sewn so it looks continuous across the seams, as shown in the following photos.

In K1, P1 ribbing (top); in K2, P2 ribbing (bottom)

(Left) Work K1, P1 ribbing on an odd number of stitches, placing a knit stitch at the beginning and the end of the right-side rows, then work mattress stitch a half a stitch from the edge. This is a good choice when the seam of the garment above the ribbing will be worked only a half stitch from the edge.

(Right) This illustrates Nancie Wiseman’s method for managing ribbing. Work K1, P1 ribbing on an even number of stitches, placing 2 knit stitches at one end and 1 at the other on the right-side rows, then seam a full stitch from the edge. This makes a neater seam than the previous example and is the best choice when the seam of the garment above the ribbing will be worked a full stitch from the edge.

Work K2, P2 ribbing on a multiple of 4 plus 2 stitches, placing 2 knit stitches at each end on the right-side rows, then seam a full stitch from the edge.

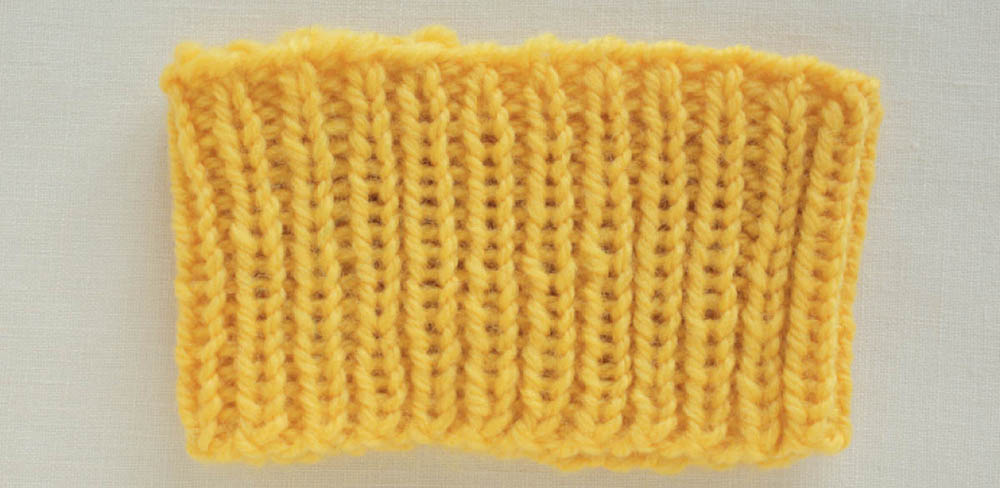

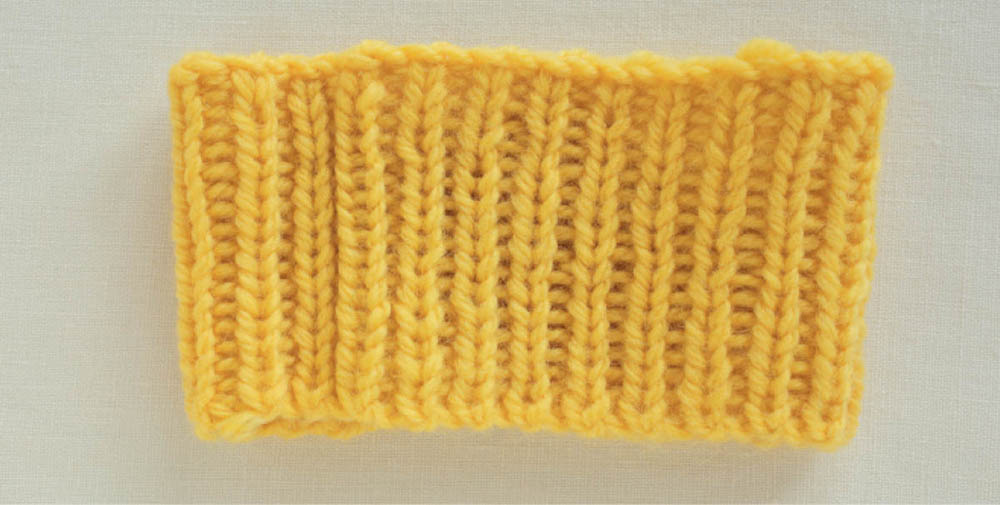

If you are unhappy with seams in ribbing or unhappy with your ribbing, you might consider making the borders circularly. My own purl stitches always look neater than my knit stitches. It’s not that they’re larger or smaller, it’s that when I purl a stitch, then turn the fabric over and look at it on the back, the two sides of the now-apparent knit stitch look closer together than the two sides of a stitch I actually knitted. The result is that my ribbing, when worked back and forth, looks inconsistent, with larger- and smaller-looking stitches alternating up each knit rib. If I work K1, P1 ribbing in the round, the wrong side (that is, the side away from me while I was making it) always looks neater because the knit stitches are narrower. For this reason, I sometimes plan ahead and work my K1, P1 borders circularly from the wrong side. When the garment is easier to work flat (for example, something with intarsia colorwork), I begin the flat pieces with a provisional cast on, complete the whole garment except for the bottom border, then remove the cast on, put the resulting live stitches onto a circular needle, and work the border down with the wrong side facing me.

Analyze your own ribbing. Does it look the same when worked flat as when worked circularly? If so, lucky you! If not, decide which one you like the look of, and which side of it looks the best. Make that the public side of your ribbing.

K1, P1 ribbing worked circularly with knit stitches looking loose (wide)

“Wrong” side of K1, P1 ribbing shown above worked circularly. Notice that the knit stitches (originally worked as purls from the other side) look tighter and neater.

K1, P1 ribbing worked flat. Ribs are inconsistent.

When you work a sweater from the top down starting with the border, you need to take into account the function of the neck border. The neck opening of a pullover needs to be big enough to go over the head, but the border mustn’t stretch too much or the garment won’t fit correctly. Choose a cast on that stretches but looks neat when relaxed. I like to begin with either the long-tail cast on or the tubular cast on. Work the border on needles two sizes smaller than the body to help it keep its shape. The pattern instructions will tell you how many stitches to cast on. If you have reversed the direction of construction and the instructions were originally to be worked from the bottom up, cast on the number of stitches specified for the neck border. After you’ve completed this border, check to see that it will pull over the head (if a pullover) and will fit comfortably around the neck before continuing with the rest of the sweater.

A point I touched on in chapter 1 is that the way you handle the stitches at the beginning and end of the row should depend on what you plan to do with those stitches later on. If it will be a finished edge (say the front of a cardigan where a section of garter stitch at the edge serves as the button band), you’ll want the edge to look as nice as possible without any further finishing. If the edge will be joined to another piece with a seam or if stitches will be picked up along it to add a border (for example, along a neckline) or another piece of the garment (as when sleeves are picked up along the shoulder and knit down), how you handle the edge stitches affects both how easy it is to complete the finishing and how good the finishing will look. Some of these choices require a few extra stitches, so you’ll need to plan ahead in order to cast on the right number of stitches or to increase to the correct number at the top of the bottom border.

Many people are taught to slip the first stitch of every row, regardless of what will be done with that edge later. This is fine if it will be an exposed edge, because it smooths the edge, preventing the alternation of long and short stitches by creating only 1 long stitch for every 2 rows. The problem with making this a habit comes when you must seam or pick up stitches along a slipped-stitch edge: there are only half as many slipped stitches as there are rows, and they are tall, loose stitches. When I plan to pick up stitches or to seam, my preference is to maintain at least 1 edge stitch in either stockinette stitch or garter stitch.

If the base fabric is stockinette, reverse stockinette, or a pattern stitch based on stockinette, I prefer to use a stockinette edge stitch. What do I mean by a “pattern stitch based on stockinette”? This is one where half the rows are mostly knitted and the other half are mostly purled. A good example would be a lace pattern where the right-side rows incorporate yarnovers and decreases to make the pattern and the wrong-side rows are just purled, or a textured pattern where a design of reverse stockinette stitches appears on a stockinette background.

It is rare for stockinette stitch edges to be left exposed. The only exception is when the edge is intended to curl. Top and bottom edges in stockinette naturally curl to the knit side of the fabric. Side edges curl to the purl side. In both cases, the edges are hidden by the curling, so it doesn’t matter what the stitches look like.

In the more frequent cases where you’ll either pick up a border or sew a seam, for a stockinette fabric, I always knit the first and last stitches (or perhaps the first and last 2 stitches) on the right-side rows and purl these same stitches on the wrong-side rows. Working 2 edge stitches (or even more), rather than 1, is particularly useful when the pattern stitch has yarnovers close to the edge, incorporates increases and decreases that distort the stitches at the edge, or is reverse stockinette that causes the edge to curl to the front of the fabric. In all of these cases, the additional stitches will make the seam easier to sew and neater in appearance.

Sometimes it’s necessary to cast on a couple of additional stitches to accommodate the edge stitches if the pattern stitch requires increases, decreases, or other stitch manipulations at the very beginning or end of the row. It’s important to realize that these additional stitches may change the fit of the garment. One more stitch at each end of the row on the front and back of a sweater means there will be 4 additional stitches. At a gauge of 20 stitches to 4 inches (5 stitches per inch — a normal gauge for worsted-weight yarn), this will make the circumference of the sweater almost an inch larger. In a finer yarn it would have less effect overall, but in a bulky yarn, with a gauge of 10 stitches to 4 inches (21⁄2 stitches per inch), an additional 4 stitches will result in a circumference that is more than 11⁄2 inches larger. If you cast on for additional stitches, be sure to consider whether the garment will be too big. Calculate the expected finished circumference of the garment, allowing for the fact that either a half or a whole stitch at each edge will disappear into the seams, depending on what seaming technique you choose.

Stockinette-based pattern stitch with one stockinette edge stitch. Border added at right.

Same pattern stitch with two edge stitches. Border added at right. With the additional stitch, the edge of the pattern is more clearly defined.

If, on the other hand, the base fabric is garter stitch, a pattern based on garter stitch (where all the rows are mostly knit stitches), or Seed Stitch (where the edge is already garter stitch), I usually use garter stitch at the edge.

For exposed edges in a garter-stitch-type fabric, you can make the aesthetic choice to take the pattern stitch to the very edge or to substitute plain garter stitch at the edges. If the edge looks messy or you don’t like the characteristic alternating long stitch and short bump at the edge of the fabric, you have the option of making a slipped-stitch edge.

Garter stitch all the way to the edges

Seed Stitch with garter stitch edge at right, stockinette at left

Seed Stitch all the way to the edge

Slipped-stitch edges are appropriate in any fabric, either to make an exposed edge look neat or when half as many stitches will be picked up along the edge as there are rows, which usually occurs only when working in garter stitch or making a ruffle.

Some knitters prefer working with slipped-stitch edges all the time, but I don’t recommend it when there will be neck or armhole borders to pick up, or when seams will be sewn. Having fewer edge stitches to work into makes it difficult to pick up enough stitches. Working with looser stitches can also result in loose, messy-looking seams.

But sometimes slipped edge stitches can be an advantage. When worked very firmly, they reduce the bulk in the seams. In thin yarn worked on very small needles, you can sometimes get away with the looseness caused by slipped-stitch edges, because even the slipped stitches are very small. Some knitters prefer crocheting their seams together. The longer, more regular stitches along a slipped stitch edge make a crocheted seam easier to execute.

The chained edge on this swatch was created by slipping the first stitch of each row knitwise, then purling the last stitch of the row. You can achieve exactly the same effect by slipping the first stitch of the row purlwise (being careful to keep the yarn in back while doing so) and knitting the last stitch of each row.

Slipped-stitch edge. Both garter stitch borders were picked up, allowing 1 stitch for every 2 rows of the base swatch. The stitches at right were picked up and knit under both strands of the slipped edge stitch. Those at left were picked up and knit under just the back strand of the slipped edge stitch, creating a ropelike effect at the inner edge of the border.

Non-slipped-stitch edge. Both borders on this stockinette stitch swatch were picked up, allowing 3 stitches for every 4 rows of the swatch. The border at left is worked in K1, P1 ribbing; the one at right is K2, P2 ribbing.

Seam in stockinette stitch with firm slipped-stitch edge. Notice how the stitches along the seam vary in tension, with loose stitches at one side crowding into tight stitches on the other.

Seam in stockinette stitch with loose slipped-stitch edge. The stitches on both sides of the seam are more even, and the seam looks almost perfect when relaxed as shown in this photo. When placed under tension, however, the gaps are very obvious.

Mattress-stitch seam in garter stitch with firm slipped-stitch edge. In garter stitch, mattress-stitch seams result in a noticeable dip or ditch along the seam line.

Mattress-stitch seam in garter stitch with loose slipped-stitch edge. When relaxed, the seam looks identical to one worked along a firm slipped-stitch edge, but when the seam is placed under tension, the gaps are obvious.

Another option that can be used on the finished edge of a garter stitch–based fabric is to work a slipped cord on 2 or 3 edge stitches. This makes a more substantial edge that is smooth and neat. To ensure that the fabric is as wide as it should be, cast on 1 or 2 additional stitches to accommodate the cord. When you reach the end of the row, bring the yarn to the front and slip the last 2 or 3 stitches. Turn to begin the following row. Pull the yarn firmly across behind the slipped stitches, and then knit them firmly before continuing across the row.

You can work this at both edges of the fabric or at just one. If the edge is shaped, all shaping should be worked in the main fabric of the knitting, not in the cord. In other words, if working decreases or increases at the end of a row, work them in the stitches immediately before bringing the yarn forward and slipping the stitches. If working the shaping at the beginning of a row, knit the slipped cord stitches first, then work the required shaping.

At the end of the row, bring the yarn forward and slip the last 2 or 3 stitches purlwise.

At the beginning of the row, pull the yarn across the back and knit firmly.

Corded edge on garter stitch

Shaping along a diagonal corded edge

The corded edge doesn’t work well with stockinette stitch fabrics (purl side shown for clarity). It is too short and pulls the edge in, but you still might choose to use it if this is the effect you want.

Working a yarnover at the beginning of every row provides neat loops that can be used for joining later on. These are particularly useful when attempting to join pieces of lace together neatly..

To make loops at the edge, work the yarnover, followed by a decrease, at the beginning of every row. If this looks messy or is too tight, try working the yarnover, knit or purl a stitch, then decrease 1 stitch.

Use a crochet hook to join the pieces. You can pull the loops themselves through each other if they are loose enough, or use an additional strand of yarn to crochet them together (see Joining Yarnover Edges).

Yarnover edges on lace prepare the pieces for decorative crocheted seams.

When shaping is involved, it’s important to plan the placement of your increases and decreases so that they don’t mess up your nice neat edges. I prefer to work all increases and decreases a stitch or two away from the edge of the fabric, maintaining the edge stitches in garter stitch, stockinette, a slipped stitch, or a cord, just as described below. Working the shaping at the very edge makes it uneven, bumpy, and difficult to deal with later on. Shifting the shaping just 1 stitch farther into the fabric leaves an even, consistent edge that’s a joy to behold and a pleasure to work along.

If you’re also working a pattern stitch, you’ll need to maintain it in spite of any shaping that’s going on. How you do this depends on the characteristics of the pattern stitch itself. See chapter 4 for case studies that investigate increasing and decreasing in a variety of pattern stitches.

Take a little time before starting your project (or at least before you progress to the point where any shaping is required), to decide what type of increase or decrease will work best for you. It will save time in the long run if you experiment with shaping in your swatch rather than in the full-size garment (see Swatching to Refine the Details). Your range of options will depend on whether you need a single or double increase or decrease (see Decreases and Increases in the appendix, for options and instructions for each type). Choose based on what looks best in your yarn and pattern stitch, what is most easily worked with your yarn and needles, and which way they slant. See the material that follows on placement and on symmetry, as well as the case studies in chapter 4 for examples.

To make the shaping disappear into a seam or when a border is picked up, work it at the very edge. Keep in mind that the edge will be irregular wherever the shaping occurs, so it may be difficult to pick up or seam neatly.

If you want a nice neat edge that’s easy to work with when picking up or seaming, place the shaping at least 1 stitch away from the edge; depending on your pattern stitch, it may look better to work the shaping 2 or more stitches from the edge. Decide exactly how many stitches away based entirely on your personal preference (see below).

Garter stitch

Stockinette stitch

K2, P2 ribbing

Slipped honeycomb stitch

Garter stitch

Stockinette stitch

K2, P2 ribbing

Slipped honeycomb stitch

Garter stitch

Stockinette stitch

K2, P2 ribbing

Slipped honeycomb stitch

Knit 2 together (K2tog) and slip, slip, knit (ssk) decreases are mirror images of each other, with one leaning right (K2tog) and the other leaning left (ssk). I like to place ssk at the beginning of the row and K2tog at the end of the row so they appear to parallel the edge. Worked in combination with a single edge stitch, the decreases make two neat columns of stockinette stitches along each edge that are easy to follow visually when seaming or picking up.

If you prefer, you can do the opposite, placing the K2tog at the beginning of the row and the ssk at the end. In fact, this is particularly nice when working stranded knitting, because it ensures that the color pattern remains undistorted up to the edge stitch, since the decreases will appear the proper color and vertical rather than slanted.

What’s important is to use one of these decreases at one edge and the other at the other edge of armholes, necklines, and tapered seams so that the two edges appear symmetrical.

Increases should also be worked symmetrically in similar situations. For example, when working a sleeve from the bottom up, work increases that slant in the opposite direction so that the edges appear to be mirror images of each other.

The knit-front-and-back (Kfb) increase doesn’t appear to lean in either direction, but it is asymmetrical, with a knit stitch on the right and what appears to be a purled stitch to the left. To make opposite edges appear to match when using this increase, you need to shift the Kfb at the end of a row 1 stitch farther from the edge. In the photo bottom right, a Kfb was worked next to the last stitch before the neck opening, so that the purled segment appears 1 stitch away from the edge. On the opposite side of the neck, the Kfb was worked in the first stitch, so that its purled segment also appears 1 stitch from the edge. The Kfb increase tightens the stitch it is worked into, and it can make the edge too tight and distort the edge stitches if worked into the first stitch of a row. To avoid this problem, shift the increases 1 stitch farther from the edge by working K1, Kfb. To make the end of a row look symmetrical, stop when 3 stitches remain, and work Kfb, K2.

Placing the K2tog before the neck opening and the ssk after it makes it look like two columns of knitted stitches parallel the neck edge.

Placing the decreases in the opposite positions, with ssk before the neck opening and K2tog after it, leaves just one column of knit stitches running parallel to the neck edge.

Symmetrical increases paralleling a neck edge, with M1R at one edge, M1L at the other

Symmetrical increases paralleling a neck edge, with Kfb increases

Before you begin a major project, consider how you plan to put the pieces together. Will all the pieces be knit separately and then joined together? Is there anything about the project that will make seaming difficult? If so, what are your options to make joining the pieces easier? Or will it all be knit in one piece, with no seams or only a few seams? Will new sections be picked up from existing sections of the garment, rather than worked separately and sewn together?

Keep in mind that at this point you’re only thinking about the best way to put your garment together — this isn’t a commitment, and you can always change your mind later. In fact, you should consider this issue periodically while you are knitting the garment, because your answers to the questions above may change as you get to know your materials and see how they behave in the fabric you’re creating.

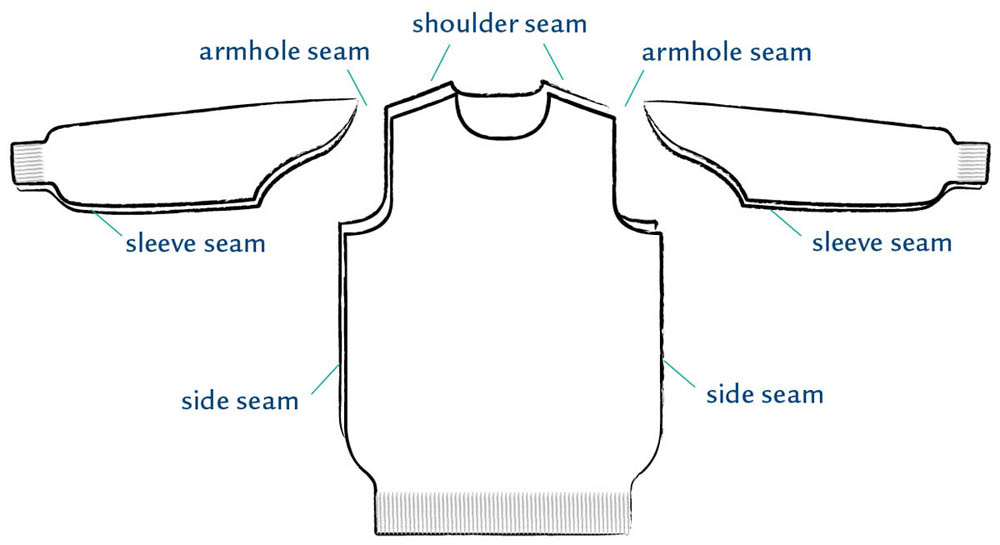

Let’s consider what seams you’ll need to deal with and what the options are for working them. In a traditionally constructed garment, worked flat from the bottom up, with separate front, back, and sleeves, there will be:

You have multiple choices for joining each of these seams. You may want to use different techniques on different seams, but if you do, keep in mind that the seams may look noticeably different from each other. I’ve provided an overview with pros and cons for each of these below. You’ll find a more detailed discussion of seaming and other ways of joining (here), and instructions on how to seam in the appendix.

Sewn seams have the advantage of supporting the garment, preventing it from stretching in length or twisting if the yarn has a tendency to cause biasing in the knitted fabric. They look the neatest and are the least bulky option for seams that support the garment. They can be used to join side edges, top and bottom edges, or a combination of the two. You can adjust the amount of stretch in the seam depending on how tightly you sew it. They can be difficult to work if the edges of the garment pieces are not worked neatly and consistently; if the yarn is dark or textured, making it hard to see what you’re doing; or if the yarn is textured or the plies stretch at different rates, making it difficult or impossible to sew with.

Joining sweater edges

Crocheted seams have the advantage of being easily worked even in yarns that are textured or otherwise difficult to sew with. They are somewhat stretchy, but more supportive than a join made using Kitchener Stitch. They can, unfortunately, result in bulkier seams.

Three-needle bind off can be used to join two pieces of knitting while binding off (for illustration, see the appendix). It is especially useful to make neat, supportive, but slightly stretchy joins at the shoulders of sweaters. It’s less bulky than crocheted seams and most sewn seams. It makes it easy to perfectly match the stitches of two pieces of knitting, but it only joins live stitches. This means you can join the tops of any two pieces if they have not yet been bound off. To join the top of a piece to the bottom of a piece, you must begin with a provisional cast on; when you remove it, you’ll have live stitches that can be used in a three-needle bind off. It can also be used to join the side edges of two pieces of knitting by picking up the same number of stitches along each edge and then binding them off together, which is very useful for joining edges that don’t match exactly, like the curved edge of a sleeve cap and the differently shaped edge of its matching armhole. The same technique is useful for joining panels or strips of knitting together. When worked from the wrong side, however, it does result in a very noticeable seam. This can be turned to advantage if it is worked on the right side with an embellishment like an I-cord bind off or a decorative bind off that looks like rickrack (see the photo for Three-Needle Bind Off).

Kitchener stitch, like three-needle bind off, must be worked on live stitches. It’s the obvious choice if you need a join that appears to be seamless and is perfect for the underarms of sweaters worked with circular or raglan yokes. This is also a good way to join a sweater knit from side to side at the center back: make the two halves identically from sleeve cuff to center, then join them seamlessly at the center back to make a cardigan, or join both the front and back to make a pullover. It’s impractical to use it to join the side seams of conventional sweaters. Sewing a side seam is a one-step process — you just sew the seam. Joining side seams using Kitchener stitch is a three-step process: pick up stitches along one edge, pick up stitches along the other edge, and finally sew the seam using Kitchener stitch. In addition to being triple the work, it will also look strange to have three rows of knitting at the side seam perpendicular to the rest of the body. Kitchener stitch provides no support to the garment at all, so should never be used for the shoulders of conventionally knit garments because they will stretch out of shape.

Another option, of course, is to combine the pieces of your sweater and knit it circularly so that it’s seamless. How to do this is discussed in detail in chapter 3. The advantage of working circularly is that you can very easily eliminate many, if not all, of the seams. This is great boon when working with a yarn that is difficult to sew with. On the other hand, it offers no support or protection against biasing when working with thick heavy yarns or fibers prone to losing their shape, such as cotton, linen, hemp, bamboo, silk, mohair, and so on. Garments that are completely seamless are more likely to be successful when worked in nice, elastic wool, and in thinner yarns (worsted weight or finer).

You can join the side edges of two pieces of knitting as you work. Complete the first section (say the back of a sweater). While you work the second section (the front of the same sweater), attach the end of each row to the back at the side seam by picking up a stitch and working a decrease to get rid of that extra stitch. The advantage of this method is that, by the time you’ve completed the knitting, you’ve also completed the seam. One disadvantage is that it can become annoying to work with as the project gets larger, heavier, and more unwieldy. Another is that the pieces are joined only every other row and the “seam” can be quite noticeable. You’ll find complete instructions on joining using this method in Knitting On.

With all of these options to choose from, it can be difficult to make decisions when you start your sweater. Luckily, you don’t need to decide everything now.

Sewing together a plain stretchy stockinette stitch fabric made from smooth, responsive yarn is a pleasant and gratifying experience once you are comfortable with the rudiments of seaming. Not all knitting is as easy to work with, however. Sewing together pieces of very loose or openwork knitting requires different techniques than sewing solid pieces. Joining very tight knitting can be just as challenging, because it’s difficult to force the yarn and needle between the stitches and it’s very hard on the yarn being pulled repeatedly through the fabric. Seams in bulky fabrics add to the bulk at points you’d prefer to be flat and supple. Fragile yarns, highly textured or fuzzy yarns, and yarns where the plies stretch at different rates can be impossible to sew with. You’ll find suggestions for coping with all of these difficulties in Joining the Pieces. It’s good to consider such problems in advance, however, because they are all reasons why you might want to employ alternatives to conventional sewn seams, such as crocheted seams, picking up sections instead of attaching them later, knitting on parallel sections as you go (Knitting On), or making yarnover edges to accommodate a decorative join.

The biggest problem knitters face when dealing with ends is trying to work with an end that’s too short. Whenever you cut the yarn or start a new ball, be sure to leave an end long enough to work with later — at least 4 inches.

When you start a new ball of yarn or run into a knot, you can splice the ends together, weave them in while you’re knitting, or leave them to weave in later. There should be only a few of these, so there’s no need to plan ahead for them.

When you’re working in stripes, with multiple colors, or with small sections of several different yarns, you’ll have far more ends to cope with, and in those cases, it is best to plan ahead. Before you start, decide whether you can carry the yarns up to future rows or rounds, or whether they should really be cut between uses. If you’re not sure, try both out in your swatch. Carrying the yarns up the edge of the fabric can distort the edge stitches, but weaving in the ends takes time and makes the edge of the fabric thicker. If you’re working circularly, you may want to carry the yarns from round to round to avoid excess ends, or you may choose to always cut the yarn and use the ends to hide the jog at the beginning/end of round (see Disguising the Jog). You’ll find details on dealing with ends in the middle of your knitting in chapter 5 as well. Methods for taking care of ends after the knitting is completed are covered in Dealing with Ends.

When you are changing colors very frequently at the beginning of a row, it’s possible to turn the ends into a decorative element, incorporating them in fringe or braids (here), but you need to consistently leave ends long enough for the fringes or braids. Leave ends longer than you think you’ll need and test out braids ahead of time on your swatch — you’ll be surprised at how much extra length they require.

If you prefer to hide the ends on the inside of the garment, you can braid them along the seam line, using a method similar to working a French braid in hair, rather than weaving in each individual end (see Working Ends in Along Seams). This is much faster than weaving in individual ends, but it can prevent the garment from stretching, so should be used only along a supportive seam. If you want to do this, leave ends that are at least 6 inches long; it’s difficult to work with shorter ends.

When the ends fall along the edge of the garment, rather than along a seam line, you can hide them inside a binding. This is just a two-layer border, with the ends encased inside. There are several ways to make bindings (see here).

If you are working your garment circularly, especially in stranded knitting, you may want to continue circularly throughout the armhole, neck, and shoulder area. Circular sweaters with raglan or circular yokes incorporate the neck and armhole openings seamlessly, but if you’re working a conventional sweater architecture, with separate sleeves, you’ll need to plan how to handle the openings for the armholes and neck. You have three options:

Steeks are extra stitches added at armholes, neck openings, and cardigan fronts that serve as seam allowances when the openings are cut open later. They allow you to make the entire garment circularly, so that you can work colored and textured patterns from the right side throughout the construction process. They work best in garments made from natural (not superwash) wool or other animal fibers, because the cut ends will felt, preventing unraveling. While they offer the convenience of working circularly throughout the garment, cutting creates a multitude of ends that you must deal with in order to complete it. See The Whys and Hows of Steeks for details on how to incorporate various types of steeks into your garments. You’ll find finishing information for cut edges here.

Adding pockets, ruffles, cords, and other embellishments is much easier if you plan for them. Purl stitches can act as markers and provide an easy place to pick up stitches. Adding a row of increases or a partial row of waste yarn while you work the garment takes the trauma out of opening up the knitting to add pockets later on.

If you want to add surface decorations like ruffles or I-cords, work purl stitches on the public side wherever they will be attached. A row or round of purled stitches makes a neat, regular base for picking up or attaching embellishments later on. To pick up along it, fold the fabric along the purled stitches, then knit up 1 stitch in each “smile” or “frown” along the purled ridge. Patch pockets can be started this way, too. Pick up stitches along the ridge for the bottom of the pocket. You can either pick up along the sides of the pocket as well, or sew the sides down once it’s completed.

Complex shapes, with twists and zigzags, are not easily picked up and knit on. Instead, outline the shape you want with the purled stitches, then use them as a guide to sew the embellishment on later. (For more information on adding pockets and other embellishments, see here.)

Picking up in each “frown” along a row of purled stitches

Finished ruffle

Rather than picking up stitches later, it’s also possible to create live stitches while you’re knitting and set them aside on a holder or an extra circular needle until they are needed. This is most easily done when the addition will be horizontal, along a row of knitting.

For a practically seamless, stretchy effect, place all your stitches on a circular needle; the ones where the live stitches will be attached should be on the thin cable of the needle. Using a second circular needle and a second ball of yarn, pick up and knit 1 stitch under the strand between each of the existing stitches where the second layer of knitting will be added. Leave these on the second circular needle until you’re ready to work with them.

Picking up and knitting new stitches between existing stitches

You can also work an increase after every stitch across the section where you need to add stitches. An M1 with the working yarn works best, because it doesn’t tighten up the fabric. On the following row, knit the original stitches and slip all the increases to a second circular needle.

M1s between every stitch

M1s slipped onto a second needle

If you are very clever with your hands, you can work this all in one step by holding the two needles together as you work across, alternately knitting the original stitches while making the increases on the new needle.

Wherever you will need an opening later, you can just knit in a piece of waste yarn for as many stitches as you need for the width of your opening. Cut the project yarn, leaving a 6-inch tail for security and to weave in later. Using contrasting yarn in the same weight as the original, knit across the width of your opening. Leave 6-inch tails at both ends of the waste yarn. Start working with your project yarn again, leaving yet another tail. When you’re ready to add the pocket or finish the opening, pick out the waste yarn, slip the stitches onto needles, and add whatever you like. The tails of the project yarn will come in handy for closing up any looseness at the ends of the opening. Note that you can only take advantage of this technique if you are absolutely sure of where the opening should be when you come to that point in your knitting. If not, then an “afterthought” addition will be a better choice. In this case, just keep on knitting. Later, when you can determine exactly where the opening should be, cut a single stitch at the center and unravel out to the sides to make the opening. See (here) for more information on making afterthought pockets.

Waste yarn at center for pocket