Shaping your garment is important on two levels. On the stitch level, you need to control how increases and decreases interact with any pattern stitches, as well as their impact on the edges of the garment pieces. Looking at the big picture, you also need to shape your garment so that it fits. In chapter 2, we discussed placement of increases and decreases, how they affect the edge of your knitting, and why this matters. In this chapter, we’ll focus first on the technical issues of shaping at the same time as working pattern stitches, then move on to how you can make adjustments to the fit and style of your garment by changing the length or width; adding darts, pleats, or gathers; and modifying the sleeve and armhole styling, the neckline, and shoulder shaping.

Although some shaping is accomplished by casting on and binding off, for the most part shaping your knitting requires the use of increases, decreases, or short rows. How you handle the shaping will have major impacts on how the knitting looks and will influence how neatly and efficiently you can complete seaming and add borders to your garment. I discussed placement and slant of increases and decreases in chapter 2. In this chapter, we’ll explore how best to integrate shaping in a variety of pattern stitches and situations.

Working “in pattern as established” while shaping the garment at the same time can be a challenge. This is one of the reasons that many patterns are written to begin at the bottom edge and work straight in pattern up to the underarm — it gives you a chance to learn the pattern stitch before adding the complication of shaping. When you begin a garment at the neck and work down, you must start the shaping immediately after completing the neck border, along with the added difficulty of placing the pattern stitch on each shoulder so that it will be centered and seamless at the center front and back, and when you reach the underarm, the pattern will be continuous where the body meets at the side seam. Unless you are already very comfortable with the pattern stitch, all this can be daunting. The best solution is to chart the shape of each piece and the pattern stitch, increases, and decreases within that shape.

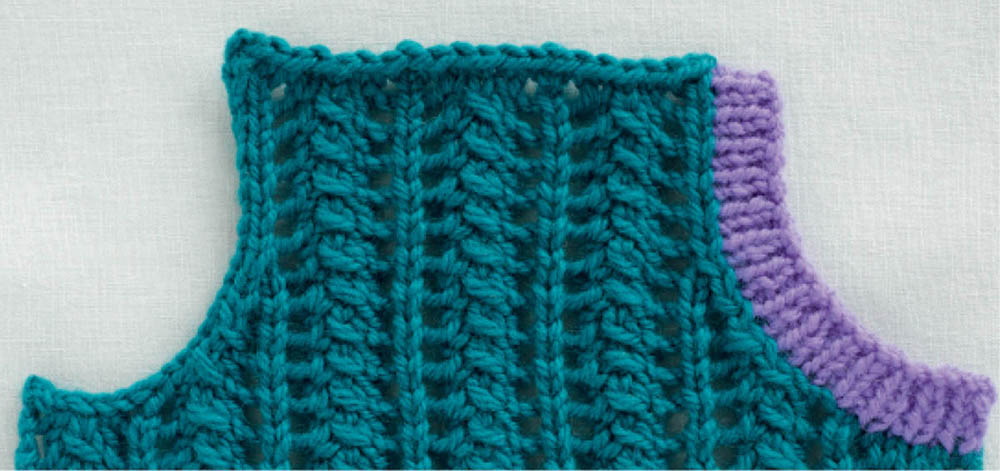

Integrating the pattern stitch with the shaping makes for perfect finishing.

You have many choices of how to work both increases and decreases, which are investigated in detail in the case studies that follow.

In the case studies that follow, rather than referring repeatedly to “increases and/or decreases” I just say “shaping” to indicate either.

Let’s say you need to decrease at the edge of a garment, which frequently happens at the underarm and at the neck. You begin by binding off some stitches, and then you decrease 1 stitch every other row to make a slanted edge. The result, when the knitting stretches, is a curve. The challenge is to make sure that, as you remove stitches at the beginning of the row, you work the pattern stitch so that it lines up with the rows you’ve already completed. You also need to make sure that the opposite sides of the garment mirror each other; if they are obviously asymmetrical, it can be ugly. Two things that may help you stay oriented are charting out the pattern stitch with the decreases and marking the repeats of the pattern in the area where decreases will occur. Case Studies #4-1 through #4-5 include a variety of situations, such as ribbing, a textured pattern, lace, and cables that illustrate some of the challenges you may face when shaping at the edge.

There will be times when you need to increase or decrease in the center of the fabric, to make a circular yoke or round collar, or to work mitered corners for a raglan sleeve or a square collar.

Mitered corners are worked just like shaping at the edges of the knitting, but with a pair of decreases for each corner. Depending on whether you are increasing or decreasing, what kind of increase/decrease you are using, and what looks best to you, you may want to place one or more stitches between the decreases or increases at the center of the miter. Case Studies #4-6 to #4-8 explore center shaping.

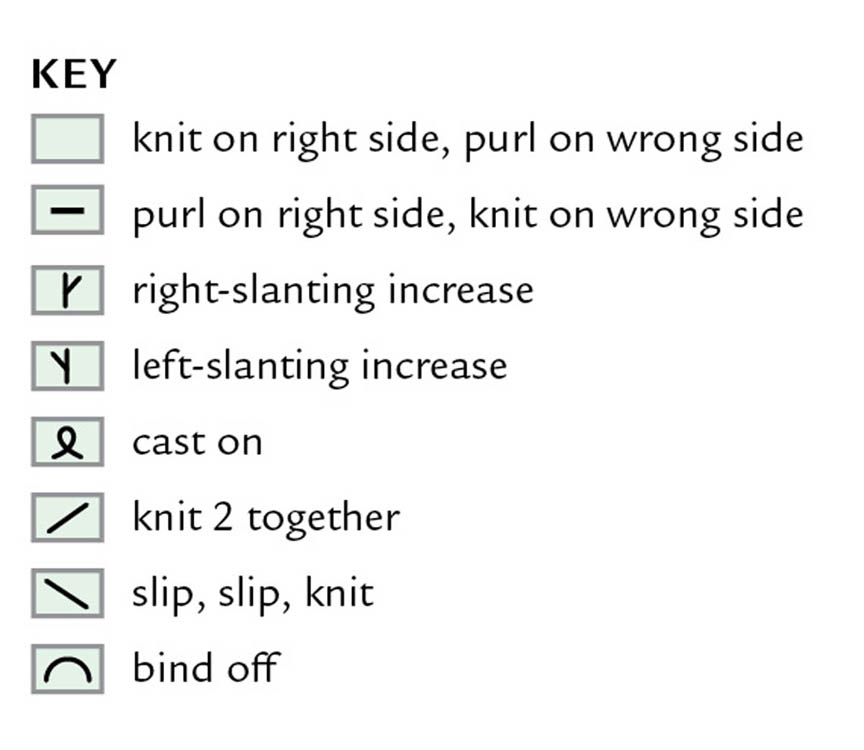

K2tog Knit 2 together

K2tog-tbl Knit 2 together through back loops

K3tog Knit 3 together

Kfb Knit-front-back

M1 Make 1

P2tog Purl 2 together

P2tog-tbl Purl 2 together through back loops

P3tog Purl 3 together

P3tog-tbl Purl 3 together through back loops

ssk Slip, slip, K2tog

ssp Slip, slip, P2tog

sk2p Slip 1, knit 2 together, pass slipped stitch over

s2kp2 Slip 2 together knitwise, knit 1, pass 2 slipped stitches over

sssk Slip, slip, slip, knit 3 together

sssp Slip, slip, slip, purl 3 together

yo yarnover

See How to Read Charts in chapter 5.

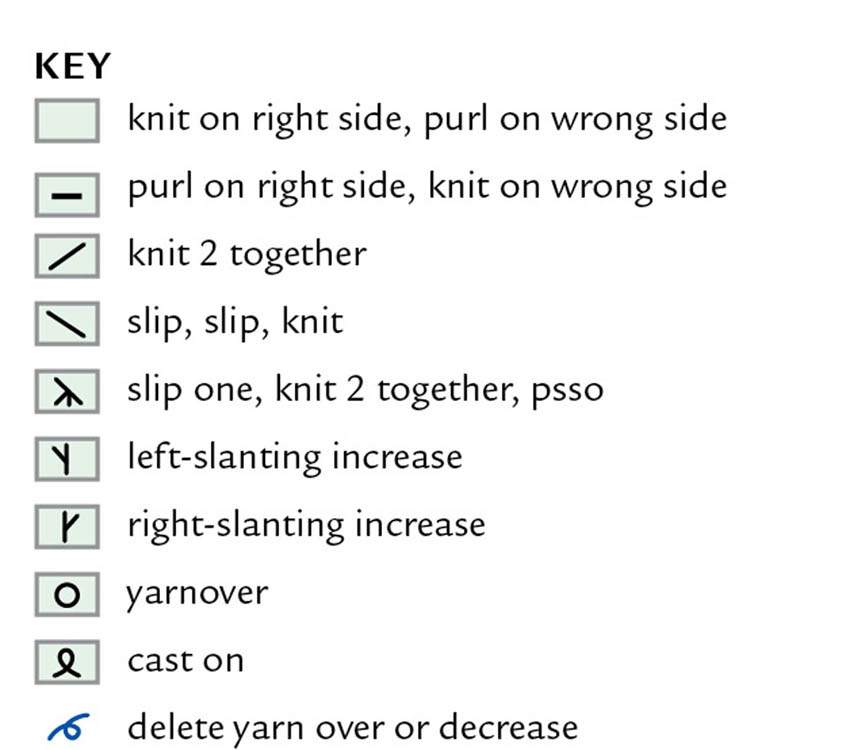

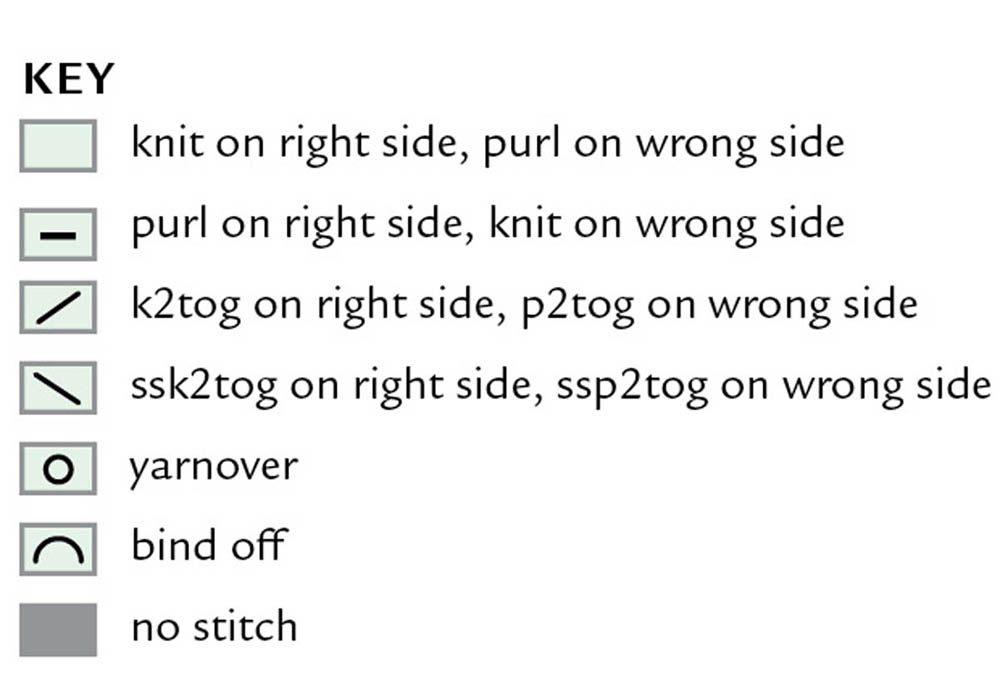

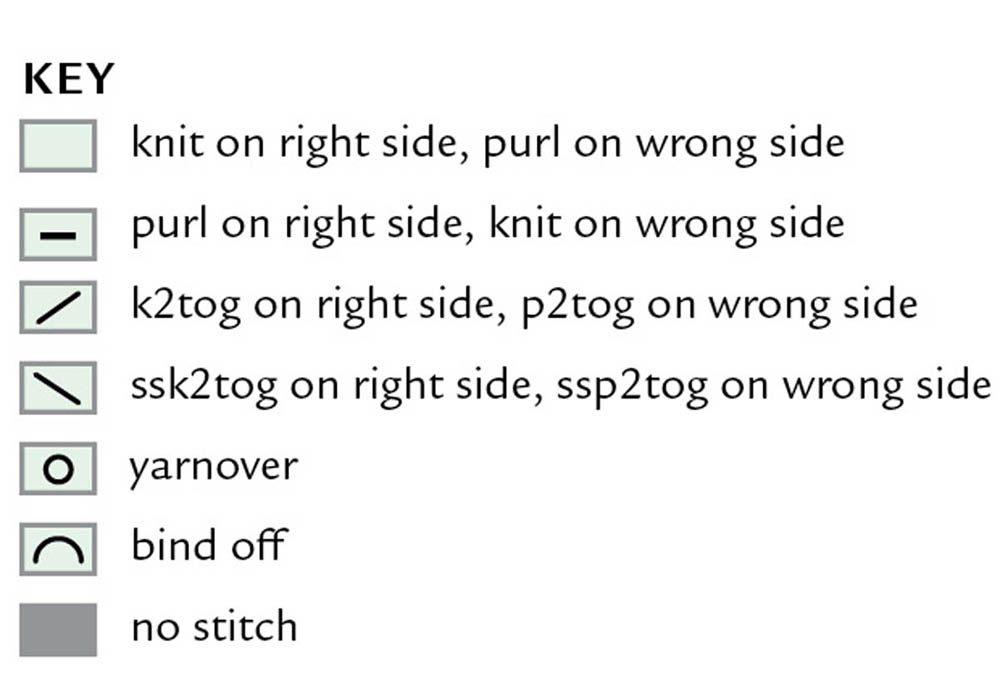

Note: These abbreviations and symbols are used in Case Studies #4-1 to #4-5 that follow.

See How to Read Charts in chapter 5.

Note: These abbreviations and symbols are used in Case Studies #4-1 to #4-5 that follow.

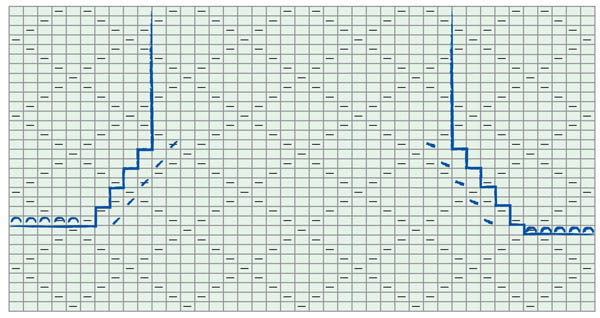

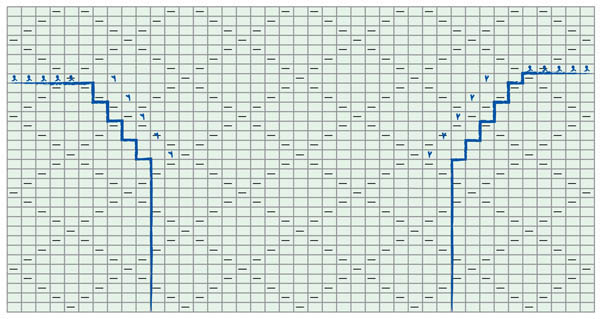

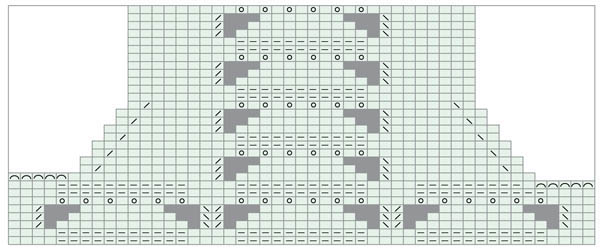

The purled stitches in Diamond Brocade don’t line up with the previous row; they are always offset 1 stitch to the left or to the right. You can use your knitting as a guide, but there is always the danger that you will accidentally shift the purled stitches in the wrong direction, so “read” your knitting carefully as you work, or make a chart of the pattern stitch and include the bind offs and decreases as shown in blue on the chart below to help yourself stay oriented.

Swatch to test bottom-up shaping

Bottom-up pattern stitch chart with bind offs and decreases marked

Top-down pattern stitch chart with cast ons and increases marked

Swatch to test top-down shaping

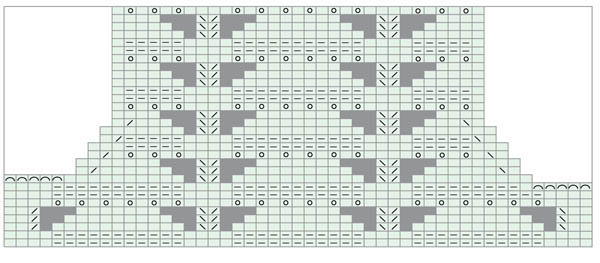

Lace patterns are worked by making yarnovers to form the eyelets and then decreasing to bring the resulting stitches back to the original number. The decreases may happen on the same row as the increases, or on later rows. Razor Shell is a good first example, because the increases and decreases occur on the same row, making it easier to analyze how to maintain the pattern while decreasing. Notice that the increases are worked as 2 separate yarnovers on either side of a knitted stitch. The decreases are worked by slipping a stitch, knitting 2 together, then passing the slipped stitch over (sk2p), which is a double decrease. The challenge is that whenever one of the yarnovers disappears at the beginning or end of the row, you must work a single decrease (K2tog or ssk) instead of the original double decrease so that you don’t end up with too few stitches. To make the pattern look consistent, choose between K2tog or ssk based on the direction that it leans, so that it matches the original pattern stitch. In this case, the double decrease leans to the left, so it’s best to use the ssk as your single decrease because it also leans to the left. On the other hand, you may want to use a K2tog when the armhole shaping intersects with the pattern stitch’s shaping along the left edge, so that the line of decreases along the edge is continuous.

As with textured stitches, it can be easier to cope with the changing number of stitches if you plot out the decreases and the pattern in a chart and if you place markers in your knitting to indicate the beginning of each pattern repeat in the area where you’re decreasing.

Bottom-up shaping in lace pattern

Bottom-up: testing shaping from the chart

Top-down shaping in lace pattern

Top-down: testing shaping from the chart

Working increases or decreases while maintaining a simple ribbed pattern is easy because once the pattern is established, it can be seen clearly, and it’s obvious how to continue in pattern: when you see a knit stitch, knit it; when you see a purl stitch, purl it.

Bottom-Up Decreases in K1, P1 ribbing. This example, with shaping like small armholes at both sides, was worked with the decreases 1 stitch away from the edge, using an ssk at the beginning of the row and K2tog at the end of the row. The result appears to be 2 knit stitches at the edge (see left edge). When the borders are picked up, 1 knit stitch remains, which integrates perfectly with the ribbed pattern (right edge).

Top-Down Increases in K1, P1 ribbing. This example was worked from the top down, increasing to make the same shape as the swatch shown above. The increases (M1s, twisted in opposite directions on the two sides) are worked 2 stitches away from the edge (see left edge). When the border is picked up, 1 knit stitch remains, which integrates perfectly with the ribbed pattern (right edge).

Bottom-Up Decreases in K2, P2 ribbing. This example was worked exactly like the K1, P1 version at left, but with the decreases 2 stitches away from the edge, so that there appear to be 3 knit stitches at each edge. When the border is picked up, 2 knit stitches remain, integrating perfectly with the K2, P2 pattern. Just like K1, P1 ribbing, K2, P2 ribbing can be shaped by increasing, taking care to place the increases so that there are 3 distinct knitted stitches at each edge. One of these will disappear into the seam or behind the border, leaving 2 knit stitches to form a full rib.

Fan Shell can be difficult to maintain in pattern while shaping is worked, because two decreases are worked on rows 3, 4, and 5, but the six increases that replace these stitches occur suddenly on row 6. The key to maintaining the pattern stitch is to understand how many stitches per repeat there should be when you complete each row, and to adjust the increases and decreases to match this at the beginning and end of every row, allowing for narrower panels of the pattern at the edges. As soon as the shaping starts, you may also simply maintain the narrower sections at the edges in plain stockinette. Or you can work the areas where shaping will happen in stockinette from the very beginning, keeping the more complicated pattern stitch in a panel at the center of the garment.

Charting, in a case like this, may not clarify things for you. With the varying number of stitches on each row, there will be a lot of “no stitch” squares in the chart that may make it even more confusing. An easy solution is to do the best you can with the work on your needles, to decrease or increase and maintain the pattern. Then, the next time you work row 1, make sure you have the correct number of stitches in the repeats at the edge. If you don’t, increase or decrease a stitch unobtrusively near the edge to correct the problem.

Fan Shell pattern with desired shaping marked and problem areas noted. (Double-click on image to enlarge).

Swatch to test shaping from chart. Plain stockinette at both sides of the shaped area, which looks awkward, although it might look fine in a full-size garment

Fan Shell showing shaping revisions from original chart and eliminating partial repeats of the pattern on both sides. (Double-click on image to enlarge).

It’s rare that you’d work a sweater in Fan Shell from the top down, because the scalloped cast-on edge makes such a nice embellishment at the bottom of a sweater (the bound-off edge usually doesn’t have as deep a scallop). In the swatch shown, the upper edge scallops because it is not constrained by the bind off, and the upside-down armhole-like shaping at either side allows the whole top of the swatch to flare. There are other cases, however, where you’d need to increase in this pattern, for example to taper a sleeve from bottom to top. Just reverse the process described above. While increasing, work the extra stitches in stockinette until you have at least enough to work half of the pattern repeat, then begin working the additional stitches in pattern. When you have enough for a full repeat, work the full repeat.

Fan Shell with shaping revisions and incorporating half a pattern repeat on both sides

Swatch to test the half repeats of Fan Shell at both sides of shaped area carrying the pattern out to the edge of the fabric

Increasing in Fan Shell

Stitches with manipulations that all go in one direction, like cables, can present difficulties when trying to achieve symmetry between the two edges of the garment. One edge may look fine, while the other looks awkward. When the decreases cut off part of a cable, you can end up with wide plain areas that look unplanned. There are several ways to improve the appearance of cables interrupted by shaping:

Decreases in cable pattern with stockinette filler stitches at edges

Decreases in cable pattern, with narrower cables at edges. It can help to work narrower cables on the remaining stitches. In this case, it might have looked even better to cross the 2-stitch cables at both edges every 4th row instead of every 8th row. In this swatch the edge stitches were maintained in reverse stockinette, but they could also be worked in stockinette for a more finished transition to the border.

Mitered corners can be worked using either a double decrease (one that turns 3 stitches into 1 stitch) at each corner or two single decreases at each corner. When two single decreases are used, it’s important to make them symmetrical, for example, pairing each K2tog with an ssk.

Asymmetrical decreases. If you use the same decrease on both sides of a corner, it will look unbalanced. This swatch shows two corners: the one on the right is made with two K2tog decreases, the one on the left with two ssks.

Symmetrical decreases with no stitches between. To make the corners look balanced, each was formed by a K2tog and an ssk. In the corner on the right, the K2tog is followed by the ssk, creating two parallel columns of stitches that clearly define the corner. In the corner on the left, the two are reversed, making the grain of the knitted columns appear to meet at the corner itself.

Symmetrical decreases with 1 stitch between. In the corner on the right, the K2tog is followed by the ssk. In the corner on the left, the two are reversed.

For a more decorative effect, you can put a small design element between the two decreases at the corner. Here, a cable highlights the corner. On the right, the K2tog precedes the corner with the ssk following it, making two columns of stitches that clearly parallel the cable. At the left, the two are reversed for a more subtle effect.

Double decreases can appear either centered or leaning, depending on which one you use. The s2kp2 in the middle is a centered decrease, slightly more difficult to work than the left-leaning sk2p at right or the right-leaning K3tog at left.

Like decreases, mitered increases can be worked as a pair of single increases on either side of the corner or as a double increase in the corner stitch.

M1 increases worked on either side of corner stitches should be twisted in opposite directions to make them symmetrical. At left, there are 3 stitches between the increases, at right, only 1 stitch.

With yarnovers, there’s no need to worry about symmetry. Just place one or more corner stitches between them.

Kfb increases must be worked so that the tiny bumps are arranged symmetrically around the corner. So that the corner stitch falls between the two bumps, work a Kfb increase in the stitch before the corner stitch and one in the corner stitch itself (right). If you like, you can place more stitches between them (left).

The double increase K-P-K into a stitch (left) is slightly bumpier because of the extra wraps for the purl, but still very similar to K-yo-K into a stitch (right).

Shaping curved structures, like a collar or a sweater yoke, while working in pattern can be challenging because you must fully integrate the pattern stitch with the decreases. This means that as the knitting gets wider, you must either add more pattern repeats or each pattern repeat must get wider. The examples below illustrate ways of doing this when working in ribbing, cables, and a lace pattern.

To make a flat circle, you need to decrease or increase 8 stitches every other round in garter stitch, 9 stitches every other round in stockinette, less than this in ribbing (because it is tall in proportion to its width), and more than this in lace because open patterns tend to be wider in proportion to their height. To calculate the shaping of a curve in any pattern stitch, see the instructions for Creating a Curved Border in chapter 8. Because knitting stretches, deforms, and can be blocked more easily the more loosely it’s knit, working loosely will make it easier to get good results.

Integrating decreases to make a circle for the yoke or collar of a sweater when working in ribbing requires that you reduce the number of stitches in each repeat of the ribbing. In this example, the swatch begins at the outer edge with K4, P4 ribbing. The first set of decreases reduces the purled stitches by one, so it becomes K4, P3 ribbing. Maintaining the 4 knit stitches makes the first set of decreases unnoticeable; you can see that the purled ribs are narrower, but you can’t tell how it was done. The second round of decreases reduces the purled stitches again, so it is now K4, P2 ribbing. Subsequent decreases remove the remaining purled stitches, so it is no longer ribbing, just plain stockinette at the center.

Circular swatch in K4, P4 ribbing, getting rid of all the purl stitches

Another approach to the same shaping in K4, P4 ribbing is to alternately reduce the number of purl stitches and the number of knit stitches, so that the ribbing gets narrower as you approach the center. Just like the previous example, the swatch begins at the outer edge with K4, P4 ribbing and the first set of decreases reduces the purled stitches in each repeat by one. The second round of decreases reduces the knitted stitches in each repeat, so it becomes K3, P3 ribbing. The decreases could have continued in this manner to the center, decreasing another purl stitch to make K2, P1 ribbing, then a knit stitch, making it K1, P1 ribbing. A final set of decreases would make the last purl stitch disappear, turning it into plain stockinette at the very center.

Circular swatch in K4, P4 ribbing, making both knit and purl ribs gradually narrower

To work ribbing while increasing, you can reverse the progression of decreases described in the previous two examples. In the example on the following page, K-yo-K was first worked in the center of the purled ribs to create new knit ribs, then in the resulting 1-stitch purled ribs to bring them back to 3 stitches each. This increase is characterized by a small eyelet (which makes the increases easy to see in this photograph), but the effect will be different depending on what increase you choose to use.

Increasing in K3, P3 ribbing by adding new ribs

Round collars or sweater yokes are worked from the top down along these same lines by leaving a hole at the center for the neck opening. The example below began in stockinette, with purled ribs created by Kfb and Pfb increases, which are practically invisible.

Increasing in K4,P4 ribbing by making the purled ribs gradually wider

When working a cabled pattern, the same approaches can be used as for plain ribs. Either get rid of all the purled stitches first, then the knit stitches that make up the cables, or gradually reduce both the purled stitches and the cable stitches. In both cases, you can still cross the cables to continue the pattern stitch for as long as possible. The swatch below began at the bottom with 6-stitch cables separated by 2 purls. After a few rows, decreases were worked to reduce the purled stitches to just 1 between each cable, and then the cables themselves were gradually made more narrow, until the swatch ends at the top with K1, P1 ribbing.

Decreasing by making both the purls and the cables narrower

Working cables while increasing reverses the process. You can effectively hide the increases in the knit stitches by making them at the center of the cable, because they are obscured each time the cable is crossed.

Increasing by making both the purls and the cables wider

This example was worked by beginning with a 12-stitch pattern repeat, then decreasing 2 stitches in each repeat until only 4 stitches remain in each repeat.

Lace pattern where size of each repeat is reduced

The fan shape of the swatch below was achieved by increasing to add pattern repeats. It begins with five repeats of 6 stitches each. K-yo-K and yarnovers are used to add stitches at the knit rib that falls between the 2 yarnovers in each pattern repeat. Until there are enough stitches to form a new rib, the new stitches are worked in stockinette. Once enough stitches have accumulated, the pattern stitch is worked continuously across the whole piece. This achieves a foliated effect, rather than the crisp angularity of the same pattern stitch in the previous example.

The same lace pattern, adding whole repeats to make it wider

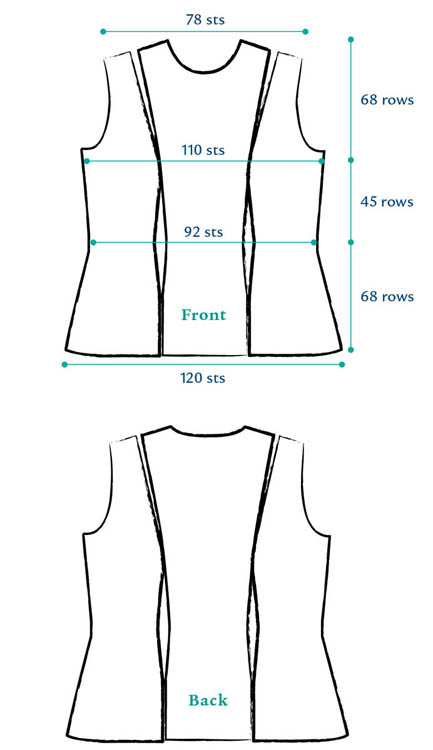

Fitting your garment means analyzing it, section by section, to determine whether it will actually fit you, and making adjustments so that it will. Garments that really fit are more comfortable to wear and look better. You may also want to change the shape for aesthetic reasons — you just want a slightly different style. Keep in mind, however, that changing the shape of the garment may affect the way it drapes and will change its proportions, so it may not end up looking or behaving the way it was originally conceived by the designer.

The changes you may want to make are covered in detail in this chapter, working from the bottom to the top of a sweater, which is the order in which you’ll most likely encounter them. (If you’re working top down, of course you’ll encounter them in the opposite order.) The material below assumes that you followed the advice in chapter 2 on selecting the size that fits you in the shoulder and neck area. This being so, you shouldn’t need to adjust the shoulder width, but just in case, I’ve included that, too.

I’ve found two very helpful tools in fitting garments. One is a pad of large sheets of 1-inch grid paper used for flip charts, which is very handy for charting out complex areas like armholes, sleeve caps, and necklines at full size. You can find pads of this paper at office supply stores. The second is knitter’s graph paper. You can use standard graph paper with square cells for working out row-by-row shaping for curves and diagonals like darts, armholes, shoulders, and neck openings, but knitter’s graph paper will give you a better feel for the actual proportions of the shaping because the width and height of each rectangle are in the same proportion as the shape of your actual stitches. An Internet search for “knitter’s graph paper” will come up with many options for creating it using a spreadsheet program (such as Excel) or downloading files you can print yourself. For the highest level of accuracy, match the proportions of the rectangles to the stitches and rows in the gauge for your project. It’s not necessary to print knitter’s graph paper at full size, unless you want to.

To determine the actual measurements of the sweater you plan to make, see chapter 1, and then decide whether the measurement of the body below the underarms needs to be adjusted.

Assuming that you’ve selected the size where the shoulder area fits, but you need the body below the underarm to be larger, there are several approaches you can take. If the hip area is the widest dimension, then you can taper gradually (see illustration, here) along the side seams or with vertical darts from the hip to the narrower area at the armhole (see illustrations, here). If the bust area is larger than the hips, you can create a gradual taper from the narrower hip circumference to the larger bust circumference, then quickly reduce to the correct number of stitches at the underarm, either by tapering at the side seams or by working decreases across the entire front to form a gather with a narrower yoke above. Depending on the required measurements of the back versus the front, both halves of the garment may be the same, or they may be different widths depending on where the alteration is needed.

In knitting you have the flexibility of decreasing to make the gathers, or of working a different pattern stitch that pulls in the fabric horizontally. To gather by decreasing, just decide how many stitches you need after decreasing, and decrease that number of stitches spaced evenly across the row. To use a pattern stitch, you’ll need to test out the difference in width between the two patterns in swatches. Some adjustment to the number of stitches may be necessary immediately before beginning the new pattern, to make it come out the correct width and to have the correct multiple of stitches to work the pattern stitch.

The additional width in the body of this sweater front was decreased across 1 row at the bottom of the garter stitch yoke, resulting in soft gathers.

The same shaping as in the example above was accomplished by using a slipped-stitch pattern for the yoke that is narrower in gauge. This assumes that the slipped-stitch pattern matches the stitch and row gauge of your original pattern instructions so that you don’t need to redesign the shaping of the armholes, shoulder, or neckline.

Again assuming that you’re making the size where the shoulder area fits, if the body needs to be narrower, you can reduce the number of stitches below the underarms by planning a gradual taper from the larger number of stitches at the underarm to the smaller number of stitches at the waist. The shaping can be worked at the side seams (see below), with vertical darts (see here), or both. Be sure to allow enough ease in the bust or chest so that the garment fits comfortably, and begin making the body smaller below the widest point in the body you’re fitting.

To make a body that tapers from the underarm or bustline to the waist, you need to know three things:

Subtract the number of stitches at the narrowest point from the number of stitches at the widest point to find the difference between the two. In most cases you’ll be shaping along the side seams (or, if you’re working circularly, where the side seams would fall), so assume that you’ll be working half of your shaping at each side seam and divide the number of stitches by two (when working flat) or four (when working circularly) to give you the number of shaping rows. Then divide the total number of rows by the number of shaping rows plus one. This will tell you how often to work increases (if working from the bottom up) or decreases (if working from the top down).

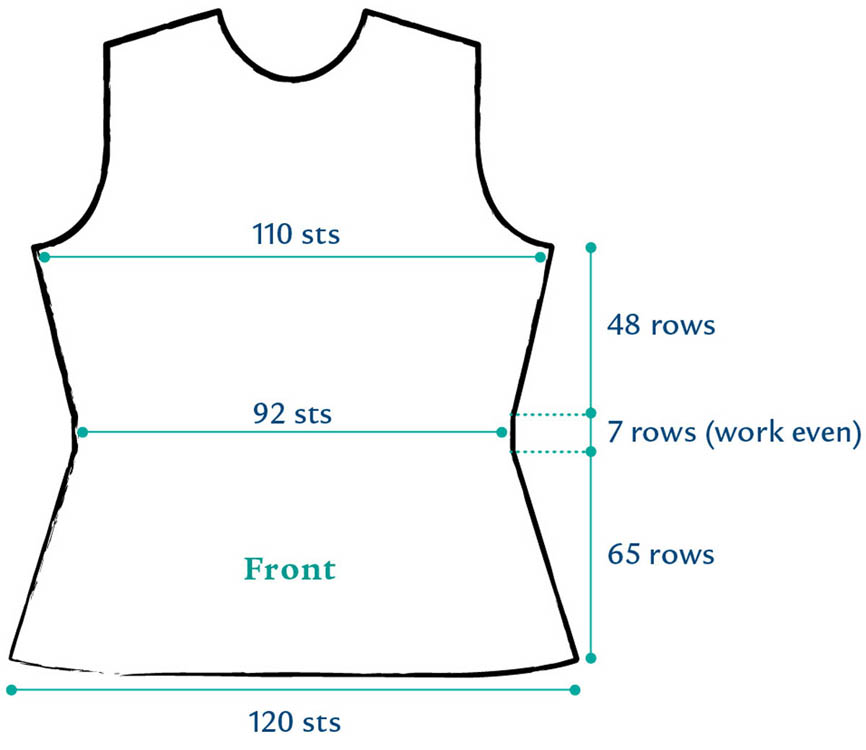

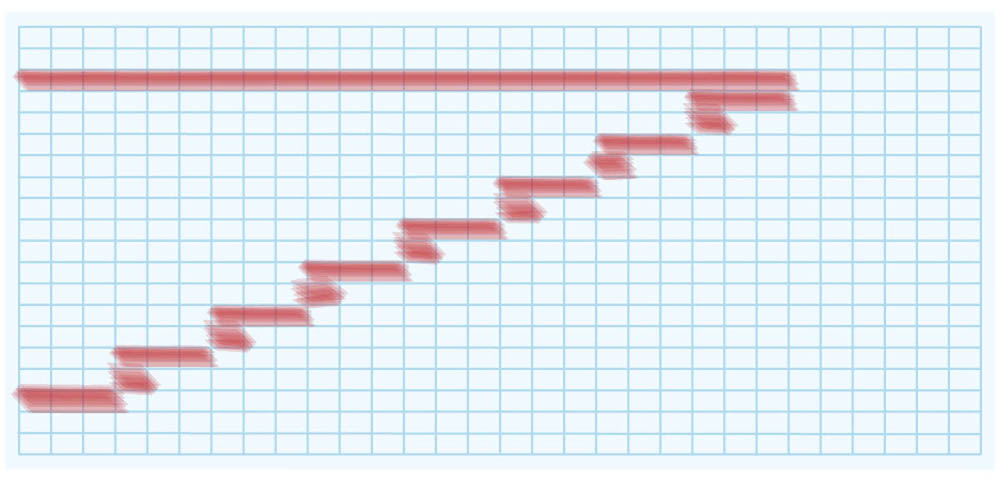

For example, the schematic (above) shows a width of 110 stitches at the bust and 90 stitches at the waist. The difference between these two is 20 stitches. Divide 20 stitches by two (assuming you will be shaping at both sides of the garment piece) to get 10 shaping rows. The distance between the waist and the bust is 50 rows. Divide 50 by 11 (1 more than the number of shaping rows) and round the result to discover that you need to work the shaping every 41⁄2 rows. Since this isn’t possible, you’ll need to work the shaping every 4 or 5 rows. It’s awkward to work some shaping on right-side rows and some on wrong-side rows, so shaping on right-side rows only is going to be easier. Here are a couple of examples of how to space the shaping out more or less evenly just on right-side rows.

The frequency of shaping rounds rarely comes out to be a whole number, so you need to plan your shaping to spread it out more or less evenly over the rows available, as demonstrated in these examples. It’s best not to place a shaping row right at the underarm, so plan the placement of the shaping to leave a few rows or rounds plain between the underarm and the highest shaping row.

Shaping a garment that gets wider from the bustline or underarm to the bottom edge is done exactly like tapering the body. You need to know the number of stitches in the widest measurement and the narrowest measurement, and the number of rows between them.

Work out a plan for shaping just as in Tapering the Body.

Tapering the body gradually from hip to underarm

Fitting the waist requires the same sort of planning as the previous two examples. A garment with a fitted waist gets smaller from the hips to the waist and then larger again from the waist to the bust (or vice versa, if you are working from the top down). You’ll need three width or circumference measurements and two lengths:

You’ll need to plan how to taper from the hips to the waist within the number of rows between those two measurements and how to taper from the waist to the bust within the number of rows between those two measurements, just as described in Tapering the Body. It’s best to allow at least a short area at the waist without any shaping, rather than decreasing to the waist and immediately beginning to increase again.

A fitted waist

Princess seams and waist darts are planned out exactly like the side-seam shaping for a fitted waist described above, but the increases and decreases occur at several other points around the garment, rather than just at the side seams.

Using the same example of a fitted garment, but working the shaping at both side seams and at two waist darts or princess seams, there are six decreases or increases on each shaping row: there is a single increase/decrease at each of the two edges and a double increase/decrease at each of the two darts. The shaping rows will be spaced much farther apart than when contours are worked only at the side seams.

Princess seams for shaping

Shaping for waist darts and princess seams can be worked using double decreases and increases, so that they appear narrow.

Working the same shaping with symmetrical single decreases and increases a few stitches apart produces a wider, but smoother effect.

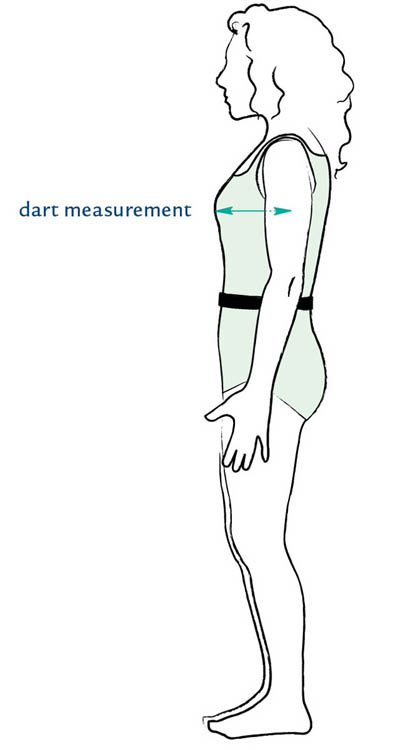

Women who are well-endowed in the bust area frequently have the problem that the bottom edge at the front of their sweaters and vests hangs higher than the back. Bust darts prevent this problem by making the front longer using short rows. If a person has very rounded shoulders or a rounded back, the opposite may occur; the bottom back of the sweater may hang higher than the front. In this case, a few short rows scattered through the back shoulder area (not necessarily lined up to form a dart) will lengthen the back so that it hangs evenly. See Wrap and Turn in the appendix for complete instructions on how to work short rows.

Everyone’s body is different, so bust-dart shaping is highly individual. Proper fit is very important. To ensure accurate measurements, wear whatever garments you normally would under the sweater or vest, fasten a belt or tie a piece of yarn snugly around your waist, and get a helper to take the following measurements with a flexible dressmaker’s tape measure.

The front measurement should be longer than the back. If it’s not, you don’t need a bust dart. The difference between the two measurements is the height of the dart. Multiply this times your row gauge to get the height in rows. For example, if the front measurement is 22 inches and the back measurement is 193⁄4 inches, then the difference is 21⁄4 inches. At a gauge of 7 rows per inch, 7 rows × 2.25 inches = 16 rows (rounded to the nearest row). Divide this number in half, because each short-row turning is worked on a pair of rows: 16 ÷ 2 = 8 pairs of short rows. (If you end up with a fraction, just round off to the nearest whole number.) This is the number of short-row pairs you’ll work to make your dart.

Holding your arm out to the side, have your helper measure horizontally from the side seam out to the point of your bust.

Because it should stop a bit short of the point, subtract 1⁄2 to 1 inch from this measurement. Multiply this times the stitch gauge to find the width of your dart in stitches. For example, at 5 stitches per inch, a 4-inch dart would be 20 stitches wide.

In our example there are 8 turning rows, and you need to figure out how to distribute 20 stitches across them. Divide the number of stitches (20) by the number of turning rows (8). You’ll probably end up with a fraction, as in this example where 20 stitches ÷ 8 rows = 21⁄2 stitches. You can’t work a half a stitch, so you’re going to need to do a little more work to figure out how to handle this. Here are three different solutions that will get you close enough for a good fit:

Quick-and-easy solution. Just round off the number of stitches to 3: 3 stitches × 8 rows = a dart 24 stitches wide. In this example, that’s more than 1⁄2 inch wider than desired. This may be okay if your dart will still stop at least 1⁄2 inch short of the bust point. On the other hand, if this would bring the end of the dart out past the point of the bust, don’t do it!

Quick-and-easy solution

Exact solution. Since 21⁄2 falls halfway between 2 and 3, you can alternate 2 stitches and 3 stitches. If you do this four times, you get exactly 20 stitches. (2 + 3) × 4 = 20 stitches over 8 turning rows.

Exact solution

Compromise solution. Reduce your dart to 7 short rows and work 3 stitches on each, for a total of 7 rows × 3 stitches = 21 stitches. This will make your dart 2 rows shorter (about 1⁄4 inch) and 1 stitch wider (about 1⁄8 inch), neither of which should make much difference in fit.

Compromise solution

If all these calculations make you uncomfortable, just sketch out a plan on a piece of graph paper, which will show you the actual shape of your dart.

Now how do you put your plan for the dart into effect? Let’s use the “exact solution” at left as an example and assume we are working a cardigan front from the bottom up. Figure out how far below the underarm the point of the dart should fall, allow for the total number of rows in the dart, and start that much below the underarm. Work the front until you get to this point.

Looking at the chart and the plan at left, you’ll be leaving 2 stitches unworked at the end of the first row. As you are approaching the side seam working across the front, stop when 2 stitches remain at the end of the row, wrap and turn, then work back to the center front. Looking at the chart and the plan at left, you’ll be leaving 3 more stitches unworked at the end of the 2nd short row. So, on the next row when you are once again approaching the side seam, stop when 5 stitches remain before the end of the row, wrap and turn. Continue this way, stopping 2 or 3 stitches farther away from the side seam until a total of 20 stitches remain unworked at the end of the row. On the next row, as you approach the side seam, work across all of these stitches, picking up the wraps and working them together with their stitches. See the appendix for complete instructions on how to wrap and turn and how to pick up the wraps.

Dart with short rows completed, before picking up the wraps

If you are working a pullover, you’ll be working the short rows at both edges. To do this, work a short row stopping 2 or 3 stitches before the side seam at one edge, wrap and turn, and then work a short row stopping the same number of stitches before the side seam at the other edge. You’ll be alternately working short rows on the right side and on the wrong side.

Darts at both sides of front in progress

If you are working circularly, you’ll make the short rows just as for a pullover, but instead of working them at the edge of the fabric, you’ll be working up to the point where the front meets the back of the sweater on one side, and then on the other.

Placing a marker at each of the “side seams” helps you stay oriented when working bust darts on a circular sweater.

If you are working from the top down, rather than from the bottom up, start the dart below the underarm, at the level where you want the point of the dart to fall. Work the short rows in reverse of the process described — turn the chart upside down to see what this will look like. On the first short row, stop 20 stitches away from the side seam. On the next short row, work past the original turning point (picking up the wrap and knitting or purling it together with its stitch) and stop 3 stitches closer to the side seam (17 stitches from the seam). Continue working 2 or 3 stitches closer to the seam on each short row and picking up the wrap at the previous turning point until you reach the seam.

The instructions on here produce a slanted dart that is very flattering for larger figures. If you prefer a dart that is horizontal rather than diagonal, you’ll need to plan it a little differently. Let’s take the same example as above, a dart 20 stitches wide and 16 rows high. First, divide the total number of rows by four, which gives you just 4 short rows. You’ll work these 4 short rows twice in the course of the dart, first working gradually away from the side seam, then back toward it. Divide the 20 stitches by the 4 short rows and you get 5 stitches. This is the number of stitches more (or fewer) that you’ll work on each short row. As you work the second half of the dart, you’ll be wrapping the same stitch that you wrapped during the first half of the dart. Be careful to pick up both the wraps from these turning points when you come to them. You’ll also be doing this on the same rows where you are wrapping and turning for another short row.

You’ll notice that this makes a dart only 14 rows high. If you want the height to be taller, then divide the total number of stitches by five instead of four. This will result in a dart that is 18 rows tall, with 4-stitch increments. Because the longest row of the dart is worked only once, you can’t make it exactly 16 rows tall. In a situation such as this, choose whichever option will work best for you — shorter or taller.

Chart of level dart 20 stitches wide and 14 rows tall

The same fit can be achieved by working either a level dart (bottom) or a slanted dart (top).

When planning your garment, you may want to work side panels in a very simple pattern stitch, garter stitch, or stockinette stitch, to make the dart easier to work, relegating more complicated patterns to the center front where there will be no shaping.

If you do decide to work a dart in a more complex pattern stitch, involving cables, twisted stitches, or increases and decreases, try it out in a swatch before working it in the garment itself, especially if the stitch count is different on different pattern rows. Charting it along with the pattern stitch could help. Experiment to see whether the dart is easier to work or looks better if begun on a particular row of the pattern stitch. The pattern repeat should also be a factor in planning your dart; for example, if you are working a pattern with a 4-stitch repeat, you may want to work the dart in 2- or 4-stitch increments on each short row, making it easier to keep track of the pattern stitch as you work. Always take care on the first complete row above the dart to work the next pattern row all the way across so that the pattern is continuous at center front, even though it has been interrupted at the dart.

This dart is worked in faggoting rib, which has a 3-stitch repeat. The short rows were worked in 3-stitch increments with no wraps, making it easy to maintain the pattern stitch. Eliminating the wrapped stitches leaves holes at the turning points, but they integrate with the lace pattern.

In garter stitch, wrap when turning to prevent holes from forming, but don’t bother to pick up the wraps later because they’ll disappear into the garter ridges.

In a knit-purl textured pattern, wrap the stitches when you turn to prevent holes from forming. When you pick up the wraps, knit or purl them together with their base stitches to match the pattern stitch.

If the rest of the shoulder area fits but the armhole is too tight or too loose, you’ll need to change the armhole. Exactly how you do this depends on what kind of armhole you’re working with. When you change the armhole, you must also change the sleeve cap to fit it.

Drop shoulder sweaters have no armhole shaping. To make the armhole bigger, just make the sleeve wider at the upper edge. You’ll need to adjust the sleeve tapering to get a smooth line from cuff to underarm.

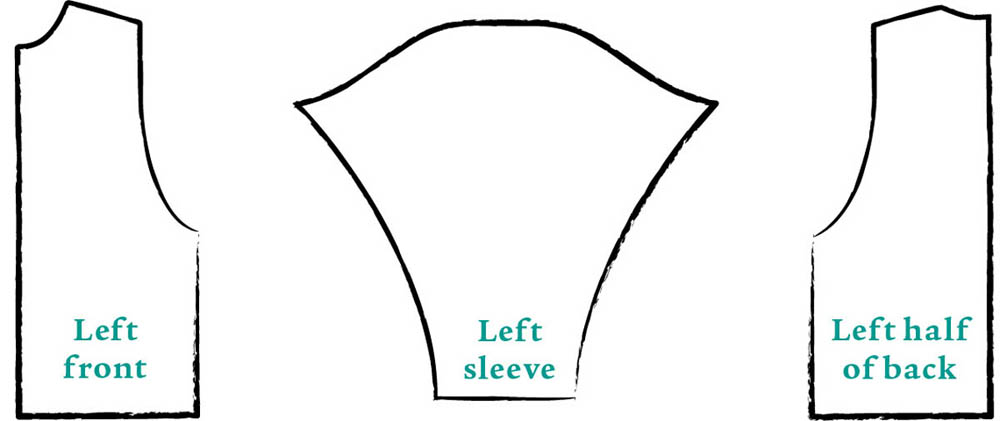

These are just drop shoulders, but with a square armhole cut into the body of the sweater so that the shoulder line falls closer to the natural shoulder of the wearer. To make the square armhole larger, work the armhole bind off lower on the body of the sweater, assuming you’re working from the bottom up. When working from the top down, make the armhole longer before you cast on for the underarm. Make sure the front and back match, and make the top of the sleeve wide enough to fit the new armhole. You’ll need to adjust the sleeve tapering to get a smooth line from cuff to underarm. Be sure to work the upper section of the sleeve straight to match the depth of the cut-in armhole, as shown in the schematic (here).

To make a round armhole taller, assuming the shoulder width of the sweater fits correctly, just make the straight section of the armhole above the underarm shaping longer; don’t make any changes to the underarm bind off or diagonal shaping. The same number of stitches should be bound off at the underarm of the sweater and the underarm of the sleeve. The diagonal shaping immediately after the bind off of both should also be the same. This means that these two sections will automatically match each other.

To fit properly, the curved section of the sleeve cap between the diagonal shaping and the center top of the sleeve cap must be the same length as, or a little longer than, the straight, unshaped front and back sections of the armhole. If the edge of the sleeve cap is longer than the armhole edge, it will need to be eased in or gathered a bit when joining the seam. When this is the case, the extra space in the sleeve cap allows a little more room in the shoulder area at the top of the sleeve for ease of motion.

To design the new sleeve cap, figure out how tall the armhole opening is from the end of the shaping up to the shoulder. Design the sleeve cap at full size on 1-inch gridded flip-chart paper. First draw the sleeve the correct width, with the underarm bind off and the diagonal shaping on both sides of the sleeve (shown in solid black). Mark the center line of the sleeve up through the sleeve cap area (shown in black dashes). Using a flexible ruler or a piece of yarn cut to the correct length (shown in green yarn), create a curve that reaches from the top of the diagonal shaping to the center point of the sleeve. Draw this curve on the paper (shown in black dots), then duplicate it for the other half of the sleeve.

Now translate your full-size drawing into knitting instructions. If you’ve drawn it on 1-inch grid paper and you know your stitch and row gauge, this is easy to do. You can write it out in row-by-row instructions, you can knit it to match the full-size pattern you drew (lay it down frequently on the pattern to make sure the shaping matches), or you can make a chart of the shaping on graph paper.

Plotting your new sleeve cap on gridded paper

There are times when you may want a more fitted armhole or a change to a more casual look. If you change the armhole style, you’ll need to change the sleeve cap to fit it.

To create a drop shoulder, get rid of all armhole shaping and work the body straight up to the shoulder. Taper the sleeve to make the top of it whatever width you like, then bind off straight across. Center the sleeve on the shoulder seam and sew it to the body, then sew the side and sleeve seams together. The width at the top of the sleeve determines the size of the armhole. (See drop-shoulder schematic, above.)

A sweater with a square armhole is shaped identically to a drop-shoulder sweater, but the point where the top of the sleeve meets the armhole falls at the natural shoulder, so the sweater appears to fit better. First determine how wide you want the shoulders to be, based on your full shoulder width measurement. Note how much narrower the shoulders are than the body of the sweater (the body width will be the circumference divided in half, if you are working circularly) and divide this difference in half to figure out the width of the bind off at the underarm. After binding off for the underarm, you’ll work straight up to the shoulder without any additional shaping. Design the sleeve as described in Creating a Drop Shoulder (above). The width of the top of the sleeve, divided in half, gives you the depth of the armhole. The sleeve is tapered up to the point where it meets the body of the garment, then worked straight for the same length as the width of the armhole bind off. (See square armhole schematic, above.)

Determine how wide the shoulders should be based on your full shoulder width and how deep the armhole should be based on your armhole depth measurement. The difference between the width of the body and the width of the shoulders, divided in half, gives you the width of each armhole. Figure out how many stitches will give you this armhole width. Bind off half of these stitches at the underarm, then decrease the rest of them, 1 stitch every other row, to make a diagonal. From this point, the armhole is worked straight up to the shoulder without additional shaping. See Adjustments for a Round Armhole for how to design the sleeve cap to fit this armhole.

A dolman sleeve is very wide at the armhole, which can extend all the way down to the waistline or to the bottom of the garment, and very tight at the wrist. Dolman sleeves can be worked separately and joined to the body (below, center), but they are frequently worked in one piece with the body (opposite, bottom).

To design a separate dolman sleeve to fit the oversize armhole, decide how deep and wide you want the armhole to be, just as for a round armhole. Draw the armhole on 1-inch grid paper, then design the sleeve cap to fit this as described in Adjustments for a Round Armhole.

If you make dolman sleeves in one piece with the body, the transition from body to sleeve can be a corner or a curve, and the easiest way to design this curve is to draw it actual size on 1-inch grid paper. To fit the sleeve length properly, you’ll need to measure the length from the back neck bone to the wrist, with the arm slightly bent. (See drawing, above.)

In order to change the full shoulder width without changing the width of the body, you have to make up the difference either in the armhole shaping or by adding shaping somewhere between the two armholes. Whenever you change the armhole shaping, it affects the shape of the sleeve cap that must fit into it. Because it’s so complicated to change the shoulders, armholes, and sleeves of the sweater, I recommended in chapter 1 that you select the size you’ll make based on the fit at the shoulder (see Choosing the Right Size). Then, all you have to do is to adjust the size of the body relative to the shoulder.

On the other hand, if you can find a size where the sleeves, armholes, and neckline are going to be a perfect fit without any adjustments, but the shoulder is just a little bit off, it may actually be easier to adjust the width of the shoulder alone, by working increases or decreases in a targeted area just below the shoulder seam.

To shape the garment adjusting only the width of the shoulder, you can work gathers (decreasing rapidly along a single row), vertical darts (decreasing or increasing along a column of stitches up to the shoulder), or pleats at the shoulder seam (folding and overlapping sections of the shoulder as you bind it off). You can also unobtrusively decrease or increase a few stitches here and there to adjust the shoulder without it being obvious how you did it.

Gathering the shoulder at the bind off is the simplest method of making a shoulder narrower and requires the least planning. You can decrease evenly spaced across the final row to get down to the correct number of stitches, or you can decrease while binding off, and you don’t need to worry about integrating your shaping with any pattern stitch.

Shoulder gathered by decreasing on the last row before binding off.

To work pleats all the way across the shoulder, you would need to have three times the width in the shoulder area than you want at the shoulder seam itself (see How to Knit a Pleat.) You can also work just one pleat at the armhole edge to reduce the number of stitches as needed. The pleat will look good only if it’s reasonably wide — about 3⁄4 to 1 inch, so you’ll need to have about double that width (11⁄2 to 2 inches) of excess stitches for a pleat to be practical.

Stop 1 row short of the completed length of your shoulder. Position the pleat so that at least 1 stitch remains beyond the pleat at the armhole edge, to allow for seaming. Following the directions in How to Knit a Pleat, slip half of the stitches you want to get rid of to the first double-pointed needle, and the other half to the second double-pointed needle.

Note that pleats make the fabric very bulky because they are three layers thick, so are most practical in garments worked in thinner yarns to make a stretchy fabric. Bulky yarns worked firmly should be avoided unless you want to make a very strong statement at the shoulder.

Pleat at shoulder. Like the other examples in this section, the width of this shoulder has been adjusted by 8 stitches, overlapped to form a pleat at the armhole edge.

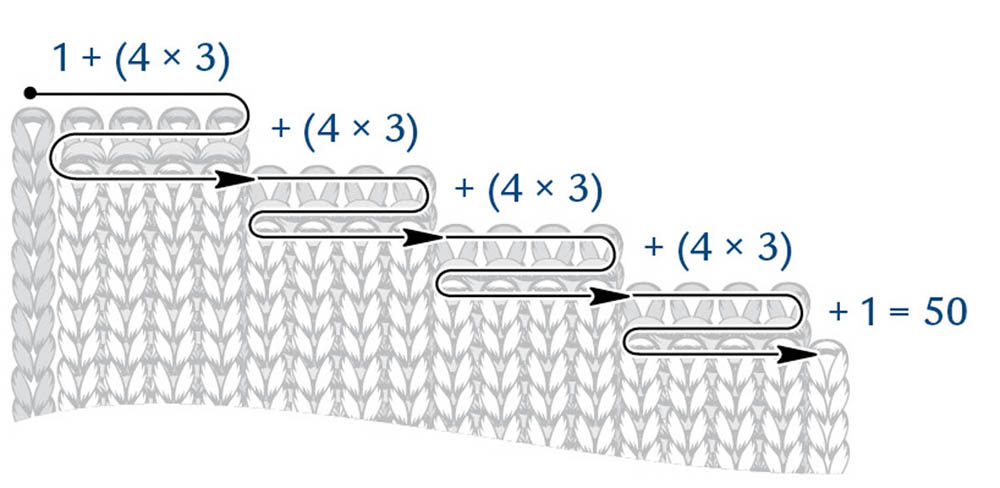

Start with three times the number of stitches you want to end with. For example, a pleat 4 stitches wide requires 12 stitches to start; after the pleat is completed, you’ll end up with 4 stitches. So, to make a piece of knitting with pleats all the way across that ends up 16 stitches wide, you’d need to start with three times that number of stitches (48), plus at least 1 stitch at each edge to allow for seaming or picking up a border, for a total of 50 stitches.

Scattering the shaping across multiple rows makes it less noticeable than working it all on one row and provides a smooth transition in the shoulder area. You can easily work decreases to make the shoulder narrower or increases to make it wider. Decide how many rows you have available to spread out the shaping and work out a plan for scattering them regularly across the available area. For example, if you want to get rid of 16 stitches over an area 32 rows long, you could decrease 1 stitch every other row. To render them less noticeable, be sure to stagger the decreases so they don’t line up.

Narrower shoulder with scattered decreases

Wider shoulder with scattered increases

Like darts worked at the waist, darts at the shoulder reduce or increase the width of the fabric along a vertical column of stitches. You’ll need to know the length (the number of rows from top to bottom) and the width (the number of stitches you want to get rid of or add) of the proposed dart. Divide the stitches by the number of rows to figure out how often to decrease or increase. Remember that you can use single or double increases or decreases.

Double decreases were worked every 4th row to reduce the width of this shoulder.

Pairs of M1 increases on either side of a center stitch were worked every 4th row to increase the width of this shoulder.

You can resize the sleeves if, for example, they won’t fit properly or because you like more (or less) ease than the pattern calls for. Changing the length can be accomplished without affecting the sleeve cap. Keep in mind, however, that changing the width at the top of the sleeve cap may require you to modify the armhole as well.

In the unlikely event that the sleeve is straight, with no increases or decreases along the seam from cuff to underarm, then just make it whatever length you like. To adjust the length of a tapered sleeve, you’ll need to figure out how often to work the required increases and decreases within the desired length. To do this you’ll need to know the following:

Once you’ve collected this information, calculate how often you need to work the shaping exactly as described in Tapering the Body.

First determine exactly where the sleeve needs to be wider or narrower. Is it at the cuff? At the underarm? In the sleeve cap? Or along the entire length? What you need to do to fix the problem depends on your answer.

If the only adjustment is to make the cuff smaller, it’s easiest just to cast on fewer stitches for the ribbed band, then increase to the specified number of stitches at the top of the cuff (or, if you are working from the top down, decrease to the number desired for the cuff when you arrive at that point).

If the cuff needs to be larger in circumference, but the sleeve cap is fine, if the sleeve needs to be wider at the underarm but the cuff is fine, or if the whole sleeve needs to be adjusted, you’ll need to know the same stitch and row counts as listed in Altering Sleeve Length. Then you can plan to taper the sleeve as described in Tapering the Body. If this results in a change in the width at the underarm and in the sleeve cap area, you’ll also need to redesign the sleeve cap so that it still fits the armhole opening, as described in Adjustments for a Round Armhole.

When working either a drop-shoulder sleeve or a square armhole and its corresponding sleeve, you can improve the fit by working the sleeve tapers at the center of the sleeve rather than at the outer edges. This naturally creates an angled sleeve cap for a better fit. How far apart you space the pair of increases (or decreases) will determine how wide the cap is at the top of the sleeve.

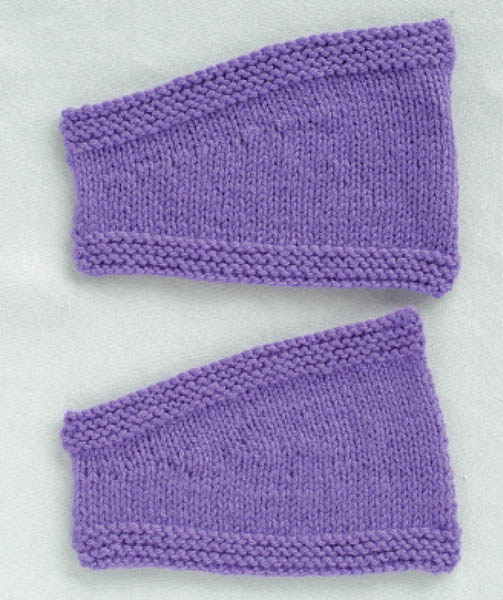

Increase placement. These two sleeves were shaped identically, but the increases on the sleeve at left were worked at the edges, and the ones on the sleeve at right were placed in the center.

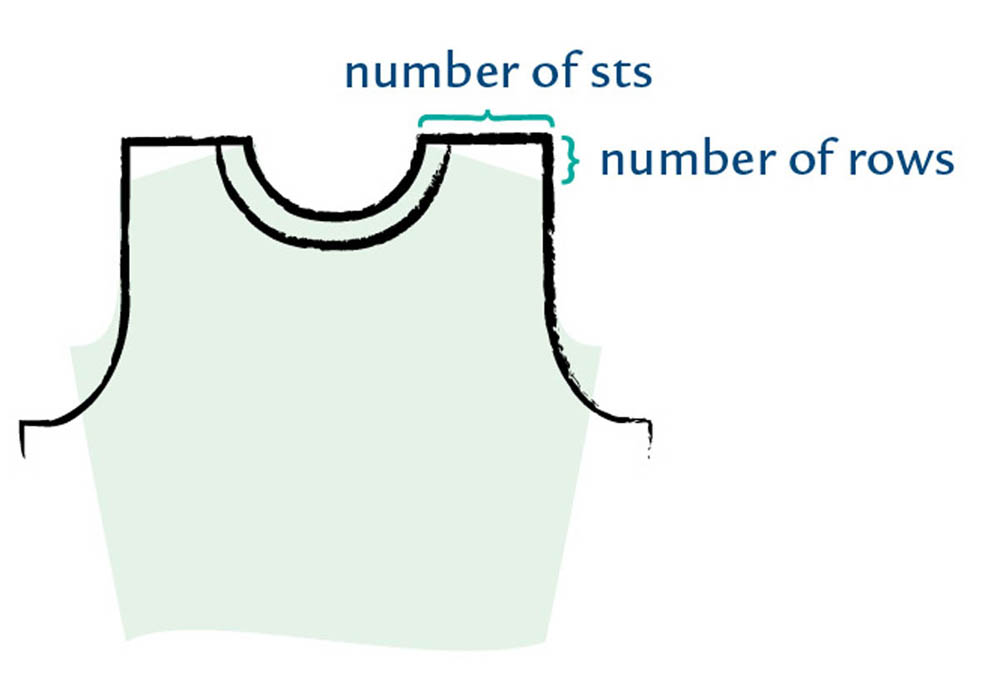

You may need to change the neck shaping to make a garment fit properly, to make a neckline higher or lower, or you may want a different type of neck opening altogether.

You’ll need to know how wide the neck opening should be in stitches (see Getting the Back Neck Shaping Right) and how deep you want the V to be in rows. Once you have this information, figure out a shaping plan exactly as described in Tapering the Body. For a good fit in a V-neck, so that it doesn’t shift from side to side, make sure the back neck fits close to the wearer’s neck and employ sloped shoulders that fit well. Be sure to allow for the width of any neck border you plan to add.

Rather than calculating the neck shaping, you also have the option of charting it (see below). Mark the width and length of the neck opening, and then draw diagonal lines from the center front at the bottom to the outer edges of the neck at the top. Draw in stair steps following the line to indicate decreases (shown in blue).

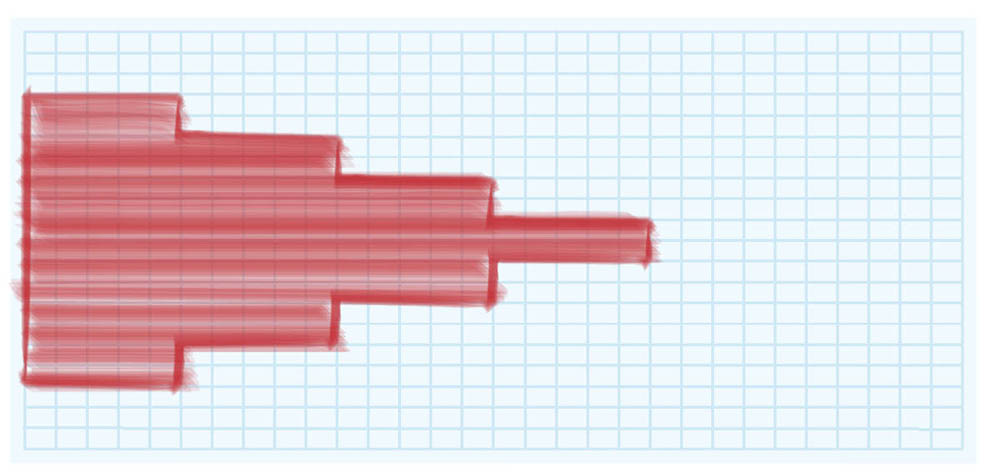

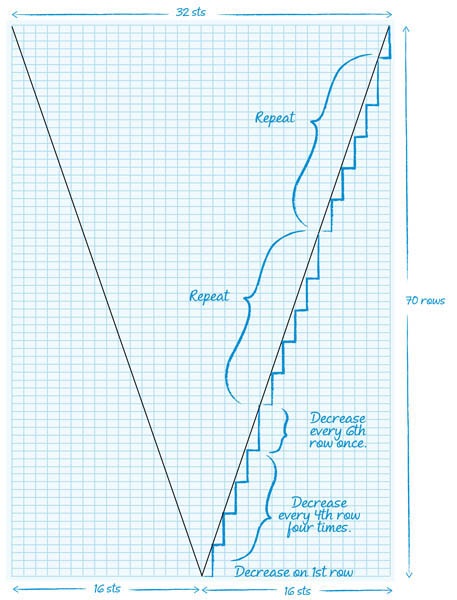

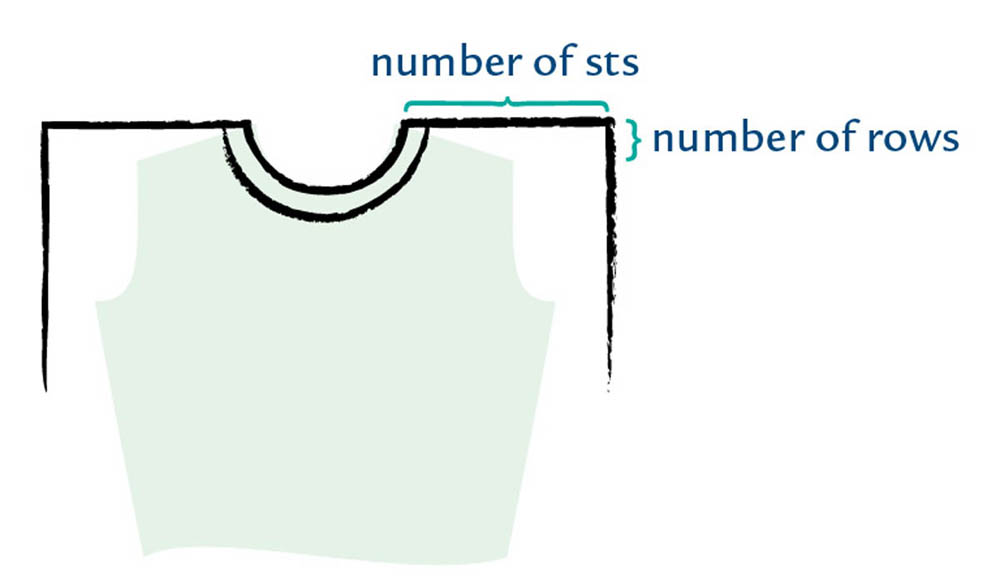

Again, you’ll need to know how wide the neck opening should be in stitches (see Getting the Back Neck Shaping Right, following) and how deep you want the neck to be in rows. Once you have this information, plot the neckline on knitter’s graph paper. First draw a rectangle that represents the width and depth of the neck opening, then sketch a nice curve within that rectangle. Finally, draw stair steps along the edges of the rectangles that represent stitches, remembering that the shaping will normally be done on alternate rows, not on every row (shown in blue on the chart). Like V-necks, round necks lie better if the back neck opening fits properly and the shoulders are sloped.

Many simple sweaters have no back neck shaping. If the fabric and neck border are stretchy, it will droop at the back neck to form a curve, but if the fabric doesn’t stretch, the sweater will sit too far back on the shoulders, the sleeves will rotate so that the top of the sleeve cap is too far back, the sleeve seam is too far forward, and the bottom of the front will fall higher than the bottom of the back. Considering all the problems that a lack of back neck shaping can cause, it’s clear that taking the time to carve out a back neck can make a very significant difference in fit, even if you change nothing else about a sweater.

The width of the back neck opening must match the width of the front neck opening and the actual width of the wearer’s neck. This can be difficult to measure directly, but you can calculate it by measuring the cross-shoulder width and the individual shoulder widths. Subtract the two individual shoulders from the full width and what’s left is the width of the neck opening (see How to Take Body Measurements).

The back neck opening should fall at the bone at the top of your spine where your neck meets your back, unless of course you want it lower. To figure out how deep this is, measure from your waist up to that bone, and from the waist up to your high shoulder (the point where your shoulder meets your neck). The difference between these two measurements is the depth of your back neck opening (see How to Take Body Measurements).

Design the actual back neck opening as described for round front necks and in the round neck chart (the top chart). The back neck will be much shallower than the front, but it should still have a nice smooth curve. Be sure to allow for the back neck border.

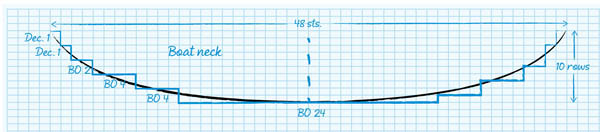

Again, you’ll need to know how wide the neck opening should be in stitches. Boat necks can be made straight across, or they can be slightly curved. If the fabric is stretchy and the neck border also stretches, it will naturally drape into a curve without any additional shaping. If the fabric is firmer, you will want a slightly curved neck opening: Follow the same procedure as for round necks to plan and chart your neck opening. Boat necks fit best when the garment is closely fitted to the body, because a sweater that has both a loose body and a wide neck opening will tend to shift back and forth on the shoulders. A slightly curved boat neck is shown above, enlarged to allow for a narrow border.

Simple sweaters frequently don’t include shoulder shaping, but, like back neck shaping, shoulder shaping can improve fit a great deal. If we stood with our arms straight out to the side all the time, unshaped shoulders would be fine. When we lower our arms and our shoulders return to their natural slope, it’s better that sweaters be shaped to fit them. When your arms are lowered, both sides of the front and back droop, distorting horizontal stripes and making the bottom edge hang lower at the side seam than in the center. In a thin drapey fabric, this may look and feel just fine. In a thicker stiffer fabric, it may look (and feel) dreadful. To work out a plan for shoulder shaping, you need to know:

Once you have these two numbers, divide the number of rows in half, then divide the number of stitches by the result. For example, if the shoulder is 25 stitches wide and the shoulder depth is 10 rows, divide 10 in half to get 5, then divide 25 stitches by 5 rows to get 5 stitches.

The shaping can be worked either by binding off or by making Short Rows. Based on our example, you would bind off 5 stitches at the shoulder on each of the next 5 rows that start at the armhole edge.

To work short rows, you’d work 5 stitches fewer on each short row as you approach the shoulder edge, just as if you were working a bust dart (see Working the Darts).

You’ll need to start working short-row shoulder shaping 1 or 2 rows earlier than bound-off shaping to ensure that the overall length is correct when the shoulder shaping is completed. The advantage of working short-row shaping for your shoulders is that you can then join the front and back using a three-needle bind off instead of sewing.

Keep in mind that shoulder shaping is not appropriate with all armhole and sleeve types. Introducing sloped shoulders into a drop shoulder or square armhole sweater may not work well unless the fabric is very stretchy, or unless you combine it with at least a shallow cap on the sleeve.

These schematics show the sweater fronts in black, with the shape of the body indicated in green.

Round armholes without shoulder shaping

Round armholes with shoulder shaping

Drop shoulder without shoulder shaping

Drop shoulder with shoulder shaping

In this example of a bound-off sloped shoulder, 5 stitches were bound off at the beginning of the right-side rows five times.

These short rows were worked by knitting across 20 stitches, turning and purling back on the wrong side, then knitting across 15 stitches, turning and working back, and so on, working 5 fewer stitches on each pair of short rows. Working short rows in 5-stitch increments forms the same shape as binding off 5 stitches repeatedly.