After you’ve made your initial choices of yarn, pattern, and needles, and planned your cast on, edge stitches, how to handle shaping, whether you want to change the order of construction from flat to circular (or vice versa) and whether you need to make alterations so the garment will fit better, at last it’s time to start knitting. In chapters 1 through 4, I covered things that you need to consider before you begin to work on your garment (or at least before you get very far into it). So here we are, halfway through the book, and finally you’re ready to cast on and get started.

This chapter addresses things you should pay attention to while you’re actively knitting the sweater. In the course of making a garment there are so many points where your judgment is required that it’s important for you to take stock of your knitting frequently. I’ve tried to highlight the moments when you’ll need to analyze the situation and decide what to do about it. Some of these will be in response to problems you’ll encounter, while others are simply opportunities to fine-tune your knitting and make it better.

For lots of reasons, knitting instructions can be difficult to interpret. One of the problems we encounter is that there are so many different ways to say the same thing. And then there are the abbreviations. It’s simple enough to remember that K1 means “knit 1” and P1 means “purl 1,” but keeping track of what sk2p or 2/2 RC mean can be daunting. (In case you’re curious, the first is a double decrease worked “slip 1 knitwise, K2tog, pass slipped stitch over,” and the second is a cable where you slip 2 stitches to a cable needle, hold it behind your work, K2, and K2 from the cable needle.) The Craft Yarn Council has published a list of standard knitting abbreviations (see Online References in appendix, for their website). For stitch manipulations not included in this list, or for variations specific to individual designers and publishers, refer to the list of abbreviations in the individual pattern, magazine, or book.

The same knitting techniques may be called by several different names; if you run across an unfamiliar technique, you may just know it by a different name. And sometimes different techniques are called by the same name; the one you know may be different from what the designer meant. If you don’t understand the instructions, they may be poorly written, or you might be misinterpreting them. Unfortunately, it doesn’t always work for the designer to add more detailed explanations — sometimes it puts people off because it makes the project seem complicated, or the additional detail is actually more confusing.

The best thing to do, when you’re not sure you understand the instructions, or the results are not what you expected, is to use common sense. Compare all the information the pattern provides (text, photos, charts, schematics) to see if they are consistent. There may be a mistake in the text that’s correct in the chart, or vice versa. Review the abbreviations to see if you are misinterpreting what they mean. Check the publisher’s website for errata, where they post corrections to patterns. Contact the designer. Search for the pattern at the online knit and crochet community website Ravelry. com to see if anyone else has commented on the problem. In many cases, there may not be a mistake, but you may be misinterpreting the pattern directions — it’s easy to do! If you discover there really is an undocumented problem in a pattern, let the designer or the publisher know, and be sure to post it on Ravelry for the benefit of others who will run into the same problem.

Like all specialized disciplines, knitting has its own jargon, which you must learn to be able to follow the instructions. One of the best ways to learn the jargon is to find a knitting mentor — an experienced knitter who can answer your questions. In the absence of such an advisor, knitting reference books and online resources like Ravelry and YouTube are invaluable. With online images, you can see what to do step by step, even when there’s not enough room in the pattern to include so much detailed information. Online video lets you watch demonstrations of techniques over and over until you understand them.

Instructions for pattern stitches that repeat can be as confusing as algebraic equations, especially when groups of repeating instructions are nested within other repeating instructions. Parentheses, square brackets, and asterisks are all indicators of sections of the row that are repeated. How do you interpret this, for example?

K2, *[(P1, K1-tbl) three times, P1, 2/2 RC] twice, (P1, K1-tbl) three times; repeat from * until 3 stitches remain, P1, K2.

First let’s look at the asterisk (*). The asterisk is the beginning of the main repeating section of the pattern. The semicolon (;) is the end of this main pattern repeat. This means that you’ll knit the first 2 stitches, then repeat the instructions between the asterisk and the semicolon until there are only 3 stitches left at the end of the row. On the last 3 stitches you’ll work purl 1, knit 2.

Next let’s look at the square brackets. They enclose a series of directions, and after the brackets it says to work everything inside the brackets twice.

Now let’s look inside the square brackets to what it is that you’re supposed to do twice. At first glance it’s fairly obvious that you work some purls and some knits into the back loop, and then you work a cable. The instruction “P1, K1-tbl” is inside its own set of parentheses, meaning that this instruction all by itself is repeated, and it says to work it three times, after which you purl 1, and then get to work the cable just once.

When you complete the square-bracketed section for the second time, you have that familiar P1, K1-tbl in parentheses to repeat three more times. After you’ve done this, you come to the semicolon and, assuming there are more stitches on your needle, you go back to the asterisk before the square brackets and repeat the whole thing all over again, until you have only 3 stitches left at the end of the row. What a relief to just work P1, K2 at the end of the row!

Writing it all out in order doesn’t really make it clearer. This is what it would look like:

Knit 2

*purl 1, knit 1 through the back loop

purl 1, knit 1 through the back loop

purl 1, knit 1 through the back loop

purl 1, cable 4 holding the first 2 stitches in back

purl 1, knit 1 through the back loop

purl 1, knit 1 through the back loop

purl 1, knit 1 through the back loop

purl 1, cable 4 holding the first 2 stitches in back

purl 1, knit 1 through the back loop

purl 1, knit 1 through the back loop

purl 1, knit 1 through the back loop

repeat from * until only 3 stitches remain at the end of the row

purl 1, knit 2

When you consider that this is just 1 row of a pattern stitch, you can see why knitting instructions are abbreviated.

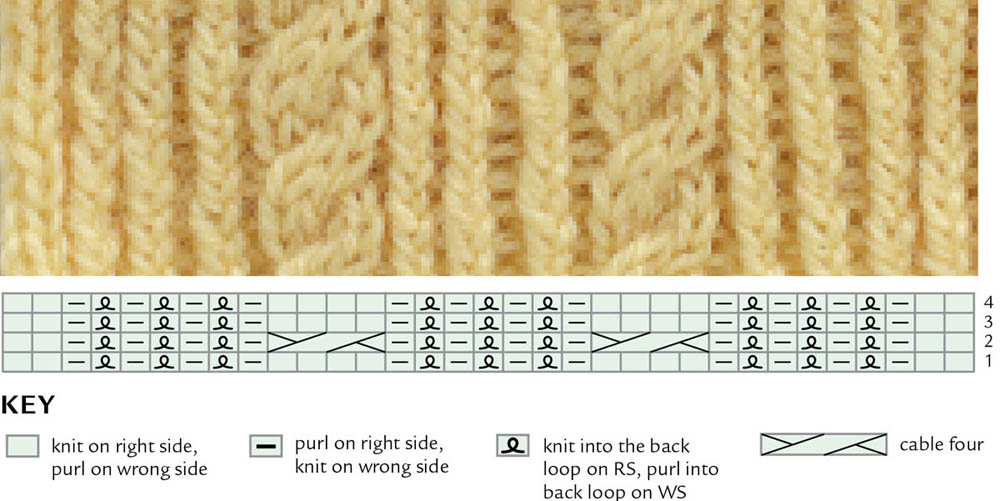

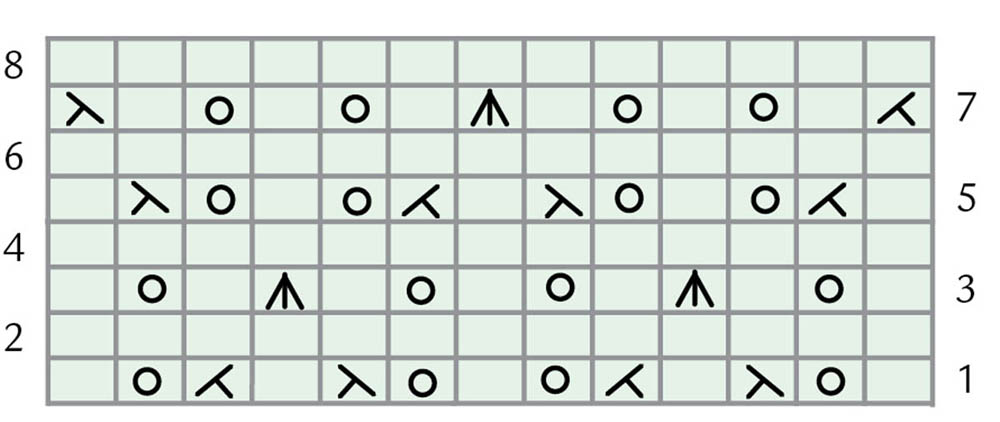

Luckily, you won’t often find instructions that are this convoluted. A good pattern writer will take pity on the poor knitter and make the instructions easier to comprehend, simplifying it by explaining the different pattern stitches and referring to them. For example, this pattern uses two main elements: Twisted Rib and a 4-stitch cable, shown in the photo and chart below.

Charted instructions make it easier to visualize what the results of complicated directions will look like. The example used above is row 2 of this chart. Clear photographs let you see whether your results are what the designer intended. (Double-click image to enlarge.)

Now it’s possible to write an understandable instruction, referring back to the explanations of the pattern stitches:

K2, *work pattern panel twice, work Twisted Rib over next 6 stitches; repeat from * until 3 stitches remain, P1, K2.

You’ll frequently run across instructions that tell you where to end one section of the garment, in preparation for beginning the next. These are intended to provide information that will make the knitting less confusing, but many knitters misinterpret them, so here are explanations of what they really mean.

Ending with a wrong-side/right-side row. This means that the last row you actually complete will be on the side specified.

End ready to begin with a wrong-side/right-side row. This means that the last row you complete before continuing will be on the opposite of the side specified, so that when you turn to begin the following row you’re in the correct place.

Ending with row x. This assumes that you are working a series of numbered rows repeatedly, for example to make a pattern or to complete a series of increases or decreases. Work until you’ve completed the row specified, and then move on to the next instruction.

There are also instructions for pattern stitches that specify exactly how a row should end. There are many ways to write these instructions, and I’ve found that knitters are prone to misinterpreting the subtle differences between the various instructions.

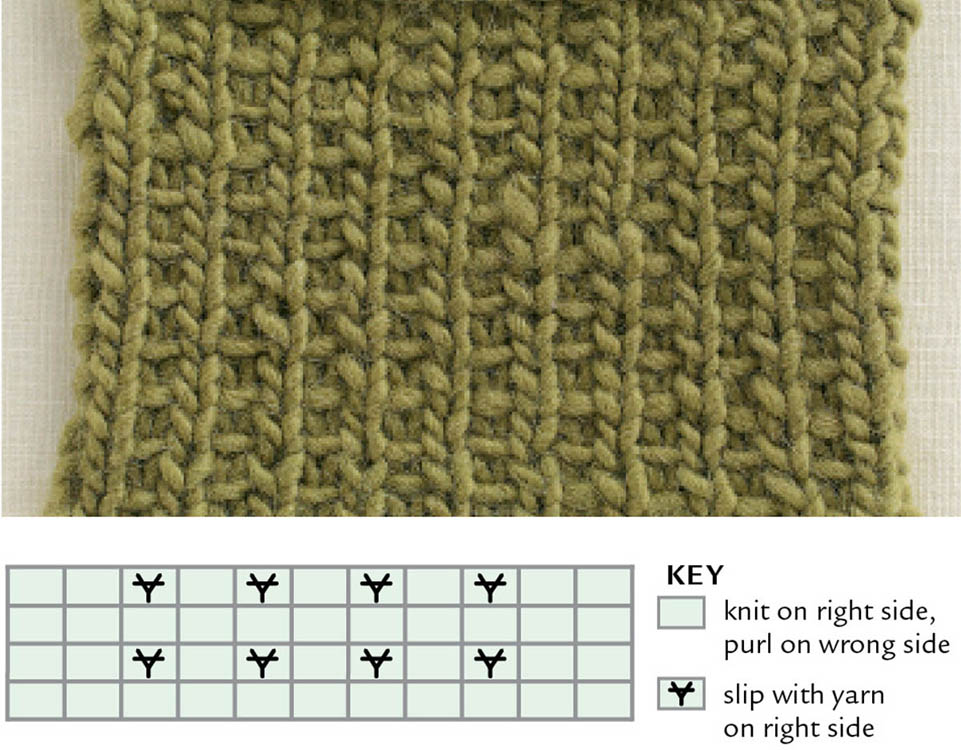

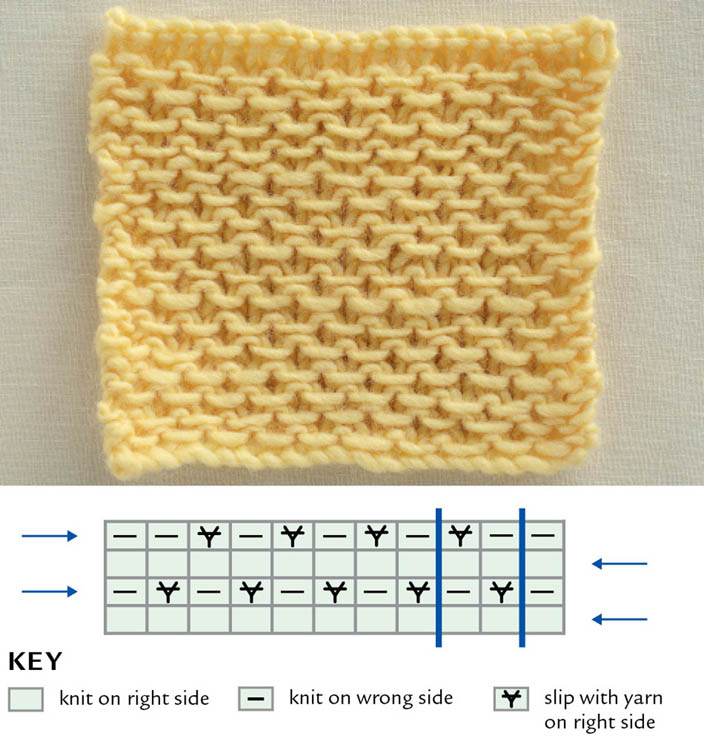

Ending ___. This usually specifies what to do with the stitches at the end of the row that fall outside of the pattern repeat. For example, if you are working a slipped-stitch pattern on an odd number of stitches, the instructions might say:

*K1, slip 1 with yarn in front; repeat from * across, ending K1.

This means that you repeat the 2-stitch pattern until you get to the last stitch, and then you knit it. The end-of-row instructions could be stated more explicitly like this:

*K1, slip 1 with yarn in front; repeat from * until 1 stitch remains, K1.

And the following instruction would create exactly the same pattern as the last two examples:

K1, *slip 1 with yarn in front, K1; repeat from * across.

The difference in the third version is that the extra edge stitch is described as being at the beginning of the row instead of at the end.

Chart and swatch for knitting instructions above

Ending the last repeat ___ instead of ___. This type of instruction is used when the last repeat of a pattern row is slightly different in order to center the pattern on the fabric or because there aren’t enough stitches left for a full repeat at the end of the row. Let’s take the same example used at left, but put 2 knitted stitches at each end of the row instead of 1. One could write the instructions any of these ways to obtain the same results:

K1, *K1, slip 1 with yarn in front; repeat from * across, ending K2.

K2, *slip 1 with yarn in front, K1; repeat from * until 1 stitch remains, K1.

K2, *slip 1 with yarn in front, K1; repeat from * across, ending the last repeat K2 instead of K1.

Chart and swatch for knitting instructions with edge stitches above

When a series of increases or decreases is worked on a single row or round, you’ll see the instructions to increase (or decrease) a number of stitches evenly spaced across or around. This happens frequently at the top of ribbing, where the transition is made to the body of the garment. Sometimes the designer will give explicit instructions how to space the increases. If these are not provided, you’ll need to figure out the spacing for yourself. There are two approaches you can take: mathematical calculation and eyeball estimates.

If you are mathematically inclined, calculate the positions of the increases/decreases by dividing the total number of stitches by the number of stitches to be increased/decreased. For flat knitting, you then adjust the position of the decreases to leave a few stitches at each edge.

For example, if you are working circularly on 80 stitches and you need to decrease 9 stitches evenly spaced, 80 stitches divided by 9 decreases = 8.888 . . . , which means it’s almost 9 stitches, so you’d knit around decreasing every 9th stitch (except that there will be 1 fewer stitch between the last decrease and the end of the round). But you must remember that each decrease uses 2 stitches out of the 9, so you’ll need to work (K2tog, K7) around in order to decrease every 9th stitch, and at the end of the round you’ll work K2tog, K6.

If you were working flat on 80 stitches and needed to decrease 9, you’d divide 80 by 9 and get 8.88 . . . , but you’d then make the first decrease after only half of the calculated stitches, to center the decreases and prevent any from falling at the edge of the fabric. So, you’d begin by working K3, then repeat (K2tog, K7) eight times, and end the row K2tog, K3.

But what if the answer is somewhere in the middle? For example, if you needed to decrease 7 stitches, 80 divided by 7 = 11.43. You need to decrease about every 111⁄2 stitches, and 2 of these will be used by the decrease, so there will be 91⁄2 stitches between each decrease. To accomplish this you’ll alternate between 9 stitches and 10 stitches, repeating (K2tog, K9, K2tog, K10) until you get to the end of the round. You won’t be able to complete the last repeat at the end of the round, but you will end up with 7 stitches decreased and they will be spaced out as evenly as possible.

If you were working flat and needed to decrease 7 stitches, you could just work fewer stitches at the beginning and end of the row and 10 stitches between each decrease like this: K3, (K2tog, K10) six times, K2tog, K3.

For increases, the calculation is worked the same way, but the adjustment for the number of stitches between increases differs depending on the increase you use. Some increases (M1, lifted increase, and yo) fall between stitches, so you don’t make any adjustment. Others (Kfb, Pfb, and knit and purl into a single stitch) use 1 stitch, so you adjust by 1 stitch. For example, if you have 70 stitches and need to increase 10, 70 stitches divided by 10 increases = 7; you need to increase every 7 stitches. To do this using M1 increases, repeat (K7, M1) around. Using Kfb increases, repeat (K6, Kfb) around. If you’re working flat, adjust so that no increases fall at the edge of the fabric by working about half of the knit stitches before the first and after the last increase.

If you dislike even the idea of calculating the stitches between increases or decreases, then it’s just as effective to estimate the spacing. You’ll need as many split markers or safety pins as the desired number of increases or decreases. Fold the knitting into halves (or quarters if it’s wide). Place a marker at the beginning and end of each half or quarter and then spread out the rest of the markers more or less evenly between these. You don’t need to count stitches, just eyeball it. Adjust the positions of any markers that look noticeably closer together or farther apart. On the next row or round, work a decrease (or an increase) at each of the marked points. So long as they’re spaced more or less evenly, it will look just fine.

Instructions for how often to work increases and decreases are usually given using this phrase, especially for something tapered like a sleeve. For example:

Increase 1 stitch at each edge every 4th row.

This is frequently interpreted wrongly as meaning, work 4 rows, and then increase. If you work 4 rows between increases, you’re doing the increases every 5th row, which will result in a taper that is significantly longer. Your garment will be too long by the time you get to the correct width. Instead, you should work 3 rows even, then increase on the 4th row.

Increasing every 5th row (left) means that you reach the desired width more slowly than if you increase every 4th row (right).

Sometimes you’ll run across similar directions for working pattern stitches. For example, when knitting in the round, the instruction to purl every 5th round makes a fabric with evenly spaced ridges.

When working flat knitting, rather than in the round, instructions to work shaping every other row are easy to follow because all of the shaping will happen on the same side of the fabric; if you increase for the first time on the right side, then you’ll always increase on the right side.

This means to continue working the pattern stitch you are already working, regardless of any increases, decreases, bind offs, or cast ons you may also be instructed to work. To do this, you must figure out how to execute each row of the pattern stitch so that it lines up properly with the row below, so that the pattern looks continuous, regardless of shaping. Shaping while working a pattern stitch is discussed in Shaping Your Knitting, chapter 4.

This little phrase strikes fear into the hearts of many knitters. It’s used when two things must happen concurrently. It may be that you need to continue a pattern stitch while working shaping.

Or it may be that you need to shape two different areas at once, for example, the neck opening and the armhole opening, or the neck and the shoulder slope. Keep in mind that you are shaping each of these at different edges of the garment.

The instructions will read something like this:

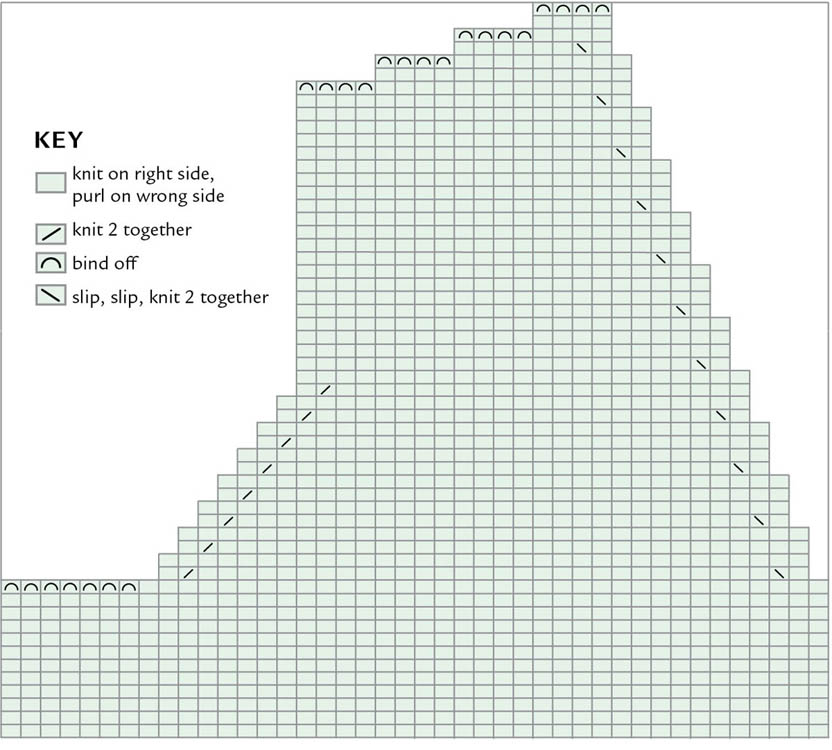

Bind off 7 stitches for underarm at the armhole edge on the next wrong-side row. Beginning on next right-side row, decrease 1 stitch at neck edge, then continue decreasing 1 stitch at neck edge every 4th row 10 more times. At the same time, at armhole edge decrease 1 stitch every right-side row eight times, then work armhole even until it measures 53⁄4 inches from bind off and 17 stitches remain, ending with a right-side row. Continuing neck decreases until complete, bind off 4 stitches at armhole edge every wrong-side row four times. This shaping is illustrated in the chart and photo opposite.

In other words, after you’ve bound off the stitches at the underarm, you’ll be shaping both the neck edge and the armhole edge. Written out row by row, this is how you proceed after binding off 7 stitches:

Row 1 (right side): Decrease 1 stitch at the beginning and end of the row.

Row 2 (wrong side): Work even.

Row 3: Decrease 1 stitch at the end of the row.

Row 4: Work even.

Each time you repeat rows 1 through 4, 1 stitch is decreased at the beginning of the row for the neck and 2 stitches are decreased at the end of the row for the armhole. After you’ve repeated the 4 rows four times, a total of 8 stitches will have been decreased at the armhole. It’s time to stop decreasing at the end of the row, but you must continue decreasing at the beginning of the row. Written out row by row, this is how you do it:

Row 1 (right side): Decrease 1 stitch at the beginning of the row.

Rows 2–4: Work even.

When you’ve worked these 4 rows five times and then worked row 1 once more, the armhole should measure 53⁄4 inches and there will be only 17 stitches left, so it’s time to start the shoulder shaping. Notice that you begin on the very next row, which is a wrong-side row. Here it is, row by row:

Row 1 (wrong side): Bind off 4, work to end of row.

Row 2 (right side): Work even.

Row 3: Bind off 4, work to end of row.

Row 4: Decrease 1 stitch at the beginning of the row.

Repeat rows 1–3 once more, and all the stitches will be bound off.

At the same time, this chart shows the armhole, neck, and shoulder shaping described above.

Following the instructions results in the armhole, neck, and shoulder shaping in this sample.

Most of the time, working with markers is very straightforward, but sometimes confusion happens because some instructions tell you in excruciating detail what to do with the markers and others tell you almost nothing. When the instructions tell you to “place marker,” then stick it on the needle tip after the stitch you just worked. Whenever you come to the marker in the future, slip it to the working needle, unless the instructions say to do otherwise. When there is an increase to be worked immediately before or after the marker, be careful to work the increase in the correct position (either before or after slipping the marker). If the increase happens to be a yarnover, the yarnover and the marker may swap positions while you’re working the rest of the row or round. Note the correct position and fix it if necessary the next time you come to that marker.

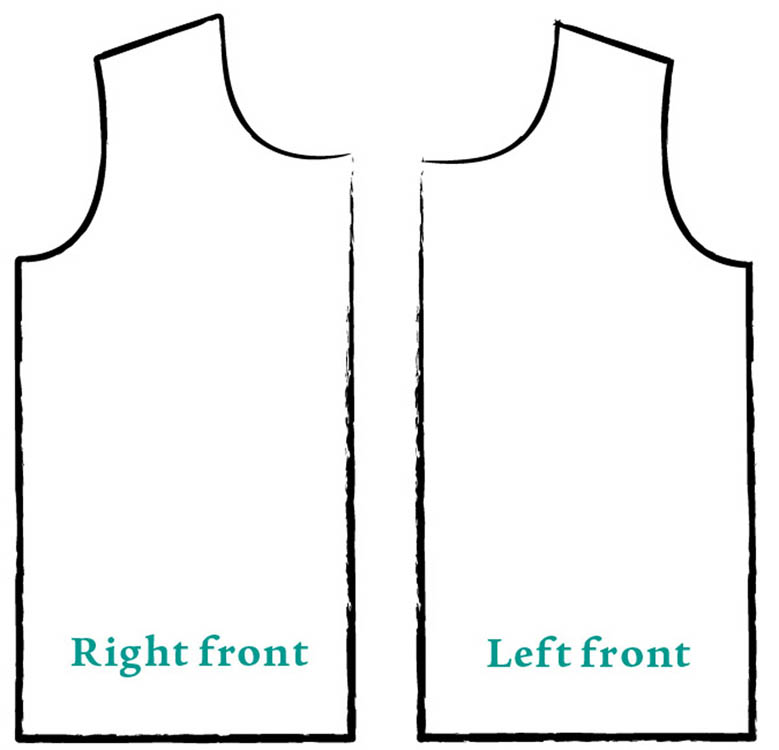

You’ll see this expression used in the neck and shoulder area of a sweater, especially in older patterns. There will be complete instructions for working the first side, whether it be left or right, then it will say to work the opposite side, “reversing the shaping.” If you’re making a cardigan, this may comprise the complete instructions for the second front! To do this, work all the edge shaping at the opposite side. For example, if decreases were worked at the end of each right-side row on the first piece, they will be worked at the beginning of the right-side rows on the second piece. Bind offs and cast ons are reversed by working them with the opposite side of the fabric facing you. For example, if the first piece was finished off by binding off 4 stitches at the beginning of 4 wrong-side rows, working the same bind offs at the beginning of 4 right-side rows will create a mirror image of the original. Note that bind-off and cast-on shaping will start 1 row earlier or later on the second piece than on the first.

Usually found in the form “Work even until . . . ,” this means to continue in whatever pattern is in progress without working any increases or decreases, so that the sides of the piece stay even.

I find the following instruction confusing because it’s imprecise: “Work to x stitches before the end of row” or “Work to x stitches before the next marker.” For example, if you are to work “to 10 stitches before the next marker,” do you leave 10 stitches unworked, or do you work that 10th stitch and leave 9 unworked? What you’re supposed to do is to leave all 10 stitches unworked.

Recently I’ve noticed a lot of patterns that say, “Work to within x stitches of the end of row” or “Work to within x stitches of next marker.” The instruction then tells you what to do with those stitches. If you try to interpret this instruction logically, it seems to indicate that as long as you have fewer stitches than are specified at the end of the row or before the marker, you’re good to go. This is not in fact the case. If it says to work until you are within 5 stitches of anything, you’d better darn well stop with exactly 5 stitches left or you’ll run into problems! What this instruction should say is, “Work until x stitches remain at the end of the row/before the next marker.”

Instructions for sweaters contain frequent references to the right and left front and to the right and left shoulders. These don’t refer to the right (or left) as you look at it, but to the right (or left) when the garment is worn. Hold the sweater front up to your own body, with the public side facing out, to identify which side is which and avoid confusion. This problem doesn’t come up when working with the back of the sweater, because the right shoulder of the back is on the right-hand side as you look at it.

For some reason, many knitters find this instruction confusing. You’ll see it most frequently as part of the instructions for picking up stitches, as in “With right side facing you, pick up 78 stitches along neck edge.” It really means just what it says. Hold the fabric with the side indicated toward you, then begin the action described.

Usually this is shortened to “pick up,” as in “Pick up 78 stitches along neck edge.” In reality, what this almost always means is to use the working yarn to pick up and knit the stitches, not to try somehow to place stitches that are part of the existing fabric onto a needle. You will very occasionally run across the instruction to pick up in one step and then to knit across the stitches in a separate step. The instructions may make this clear by saying, “pick up (but do not knit).” Picking up without knitting only works well with slipped edge stitches, which are larger and looser than regular stitches at the edge of the fabric. For a lot more detail on this, see Planning for the Best Edges and Seams in chapter 2, Neck, Armhole, and Front Borders in chapter 8, and Pick Up/Pick Up and Knit in the appendix.

Charts make it easy to work pattern stitches and color patterns flat or circularly, without having to refer to the instructions in words. Charts are laid out in a grid, with one square representing each stitch. They portray textured pattern stitches using individual symbols for the various stitch manipulations, such as purls and slipped stitches. Color charts may show the actual color of each stitch, or may use a symbol for each color so that it’s easy to substitute colors to create different colorways. The Craft Yarn Council has developed standard symbols for these charts (see Online References for the website).

When representing flat knitting, charts usually show a single pattern repeat plus any additional stitches that serve to center the pattern on the fabric. In circular knitting there are usually no centering stitches because the stitch count is generally an exact multiple of the pattern repeat, so the pattern stitch repeats around perfectly. The repeating section of the chart is usually indicated by a wide bracket across the bottom or heavy vertical lines (sometimes in a contrasting color) on each side of the repeat. If there are no special markings, check for supporting text instructions that clarify which stitches are in the repeating section of the pattern. Each horizontal row of a chart represents a row of your knitting. Each square across the row represents an individual stitch. Because the first row hangs at the bottom of your knitting, the first row of a chart is the bottom row. For the same reason, if you are making a sweater from the top down, the images on the chart will be upside down, because your sweater is upside down as you work it.

In very rare cases, knitting charts are not based on a grid, for example, when they represent circular or swirled knitting. In these cases the designer must invent a new system, which will be explained in the supporting text.

Both charts result in this same knitted fabric.

When working flat, read the right-side rows from right to left, because that’s the direction standard knitting is worked. Work any edge stitches at the beginning of the row, work the pattern repeat over and over until you approach the end of the row, and end with any edge stitches at the end of the row. Turn your knitting.

When you work the next row across the wrong side of your knitting, you must read across the next higher row of the chart in the opposite direction, from left to right. First work any edge stitches at the left edge of the chart, then work the pattern repeat across, and finish by working any edge stitches at the right edge of the chart. At the same time, you need to realize that the chart shows what you will see on the right side of the knitting, not what you will do on the wrong side. If you knit a stitch on the wrong side, it will look like a purl on the right side. On the wrong-side rows you must, therefore, reverse all the knits that you see in the chart for purls, and substitute purls for knits. The key to your chart probably will have a reminder that the symbol for a knit stitch means to “knit on the right side and purl on the wrong side” and that the symbol for a purl stitch means to “purl on the right side and knit on the wrong side.”

Continue moving up 1 row on the chart each time you complete a row of your knitting. Remember to read all the right-side rows from right to left and the wrong-side rows from left to right, and to reverse the knits and purls when you are working on the wrong side.

Assuming you always work with the right side facing you in circular knitting, begin reading the chart at the bottom row from right to left, just like flat knitting. Work the pattern repeatedly until you get to the end of the round. Then, move up 1 row on the chart and follow it from right to left, working the pattern repeat in the new row until you again reach the end of the round. Always read from right to left and always move up 1 row in the chart each time you begin a new round.

Worked flat. Blue lines mark the pattern repeat, and arrows show the direction of work for each row.

Worked circularly. Blue lines mark the pattern repeat, and arrows indicate that the direction of work is the same on every row.

Sometimes a chart will be provided just for a panel that is worked on part of each row. For example, a complex cabled pattern may be charted, while the stitches on either side are worked in something simple, such as Seed Stitch. In these cases, the section that the chart represents is usually designated by markers, and the instructions tell you to work in Seed Stitch up to the first marker, work the center panel based on the chart to the following marker, then work to the end of the row or round in Seed Stitch.

Some knitters work in the opposite direction, holding the working needle in the left hand and proceeding across each row from left to right. Many other knitters who normally work in the standard direction have learned to “knit to and fro,” which allows them to reverse direction across the row for convenience when working short rows or entrelac (see Knit To and Fro in the appendix).

The explanations for charts assume that you are a standard knitter. If you are working in the opposite direction, then read the chart in the opposite direction to match your knitting. When the wrong side is facing you, be sure to substitute knits for purls and vice versa.

Be aware, though, that this may not work in every case. For example, if there are Kfb increases at both edges of the knitting, to make them appear symmetrical they are worked 1 stitch farther away from the end of the row than from the beginning of the row, because the bump caused by knitting into the back of the stitch always follows the stitch itself. A mirror-image knitter would also need to work a Kfb increase at the beginning of the row 1 stitch closer to the edge than at the end of the row, but this would be at the left side of the chart (and the knitting) rather than at the right.

Decreases are also reversed for mirror knitters. K2tog slants to the left, and ssk slants to the right. Chart symbols, however, indicate the slant of the decrease, so if you use a decrease to match the slant shown on the chart (rather than that designated in the key), the results should be perfect.

Occasionally, only every other row or round will be included in a chart. For example, wrong-side rows or plain rounds may be eliminated to reduce the size of large lace charts. In flat knitting, the right-side rows are the pattern rows and the wrong-side rows (that do not appear) are simply purled, or the stitches are worked “as established,” knitting the knits and purling the purls. When knitting in the round, the plain rounds would be either knitted or worked “as established.” If every other row is omitted from the chart, it will explain this in the instructions. The row numbers will increase by increments of two on these charts, and you’ll need to remember to work the wrong-side rows or plain rounds before moving up to the next row of the chart.

Chart showing all rows

Chart showing only pattern rows

Knits are usually shown as an empty square. On right-side rows, knit these stitches. On wrong-side rows, purl them (so that when you turn to the right side they look like knits). Each pattern should include a key to the symbols, which provides guidance such as “knit on the right side, purl on the wrong side.” Purls are usually shown as dashes, shaded squares, or dots. On right-side rows, purl these stitches. On wrong-side rows, knit them (so that when you turn to the right side they look like purls).

If the pattern has a different number of stitches on some rows, you may see a black or dark gray square mysteriously labeled “no stitch.” This seeming contradiction means that, while there’s a placeholder in the chart for a stitch that has disappeared or will appear on a subsequent row, there’s currently no corresponding stitch on your needle. When you come to “no stitch” in the chart, ignore that square on the chart, skip to the next square on the chart that represents a real stitch, and continue working with the next stitch on your needle. (See list of Symbols commonly used in charts.)

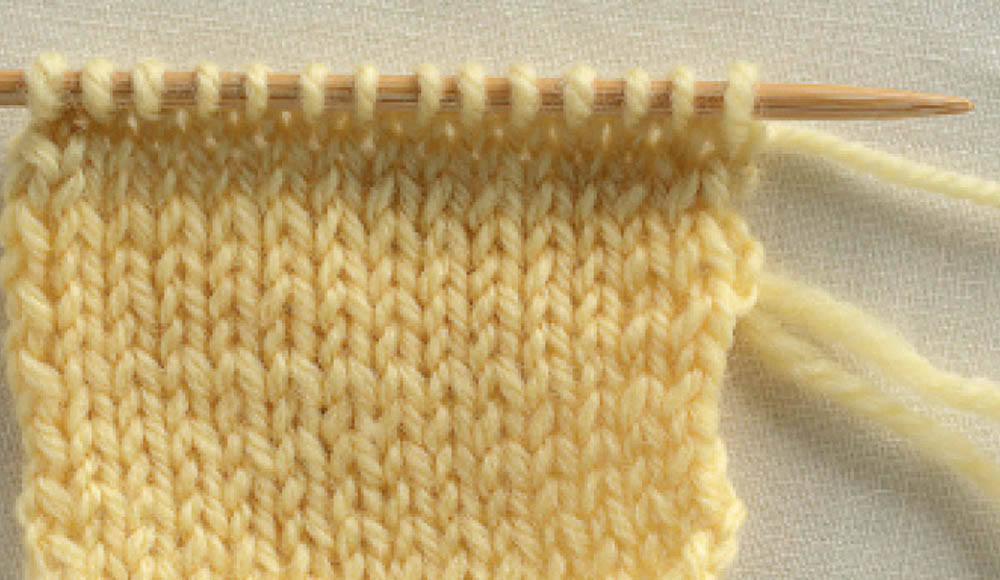

There’s a tendency, when happily knitting from someone else’s instructions, to get the project underway and then shift to automatic pilot, knitting along without paying much attention to how things are going. Even though I’m a designer and write knitting patterns, when I’m working from someone else’s pattern, I tend to do exactly that, suspending my judgment and blindly following the instructions. There are a lot of reasons why this is a bad idea. It’s easy to misinterpret the instructions and to blissfully knit several sections of a garment before you realize that something is radically wrong — like it’s three sizes too small. This can happen if your gauge changes in the course of the project, and, as a result, part of the garment may end up significantly different in size than the rest. Or you may drop a stitch or make a mistake in a pattern stitch and not notice until much, much later, when it’s much, much more work to correct the problem. Or you may misinterpret instructions for decreasing to shape the armhole or neck, for example working them every other row when they should have occurred every fourth row. For all these reasons, it’s important to stop fairly frequently and evaluate your knitting. Here are the questions you should be asking yourself.

Is the full-scale knitted piece consistent with your swatch? Does it look looser or tighter than the swatch? Measure a larger area than you could in your swatch to see if it’s the correct gauge.

If there are any problems, decide how disastrous the predicament is. Will it be just a tiny bit off in size, or will it be much too big or too small? If it’s not going to fit, stop and take action right away. You might try changing needle size in midstream. If changing needles doesn’t look too bad, continue on, keeping an eye on things to see whether they continue to look good. If changing needles looks bad, you may need to unravel back to the border and work from there, or you may just need to cut your losses and start over.

Measure the dimension of the piece you’re working and check it against the schematic to see if it’s coming out the right size and shape overall. Eyeball it and think about whether it looks the right size to you. If you’re partway through a section, estimate what the length and width should be at this point, and whether it will end up the right size when completed. If it seems to be getting too wide too quickly or too slowly, you can adjust the spacing of any increases or decreases as you go, to make it come out just right. See Fitting Your Garment in chapter 4, for modifying the length and width of various garment pieces.

If you’re working from the top down, be sure to check the fit of the neck opening, armholes, and shoulders when you complete them, before continuing with the body and sleeves. These are difficult and time consuming to correct after the rest of the sweater has been completed. Place the stitches on a long circular needle, two circulars, or a piece of yarn, so that you can actually try it on for fit. Circular needles are the most efficient choice, because you can knit the stitches onto them (instead of wasting time slipping them back and forth), and then keep right on working on the circular needle(s).

Take a good look at the fabric. Stop and fondle it often. Do you like the way it looks and feels? Does it seem appropriate for what you’re making? If it’s stiff and thick or very soft and stretchy, will it behave the way it should in the finished garment? A stiff, thick fabric must be fitted very carefully to make a comfortable sweater. A very stretchy fabric tends to stretch out of shape. If you think there’s a problem, try to figure out why it’s happening. Did you substitute a thicker or thinner yarn that’s causing the problem? Are you really getting the correct gauge? Try swatching again with a different needle size (larger to loosen up the fabric; smaller to tighten it) and see whether you can get a fabric you like at the correct gauge. If you can, you’ll need to start the project over. If you can’t, it may be that this isn’t a good project to finish — perhaps you should do something else with this yarn.

Does the pattern stitch look right? Compare it to any photos of the garment. If it looks like the pictures, all’s well. If it doesn’t, but you like it anyway, that’s fine, too. If it looks awful, you need to do something about that before you go any further.

Be sure to take a look at it from a distance to see whether the pattern and the yarn work together. Does the pattern disappear at a distance? If a textured pattern doesn’t show up, you can sometimes improve the stitch definition by knitting it more tightly, but occasionally it’s just a matter of the yarn structure; see chapter 2 , on how to select the best yarn for your project. If a color pattern doesn’t show up, it may be that you need more contrast between the colors. If they are all light, all medium, or all dark, they will tend to blend together from a distance. This is a problem you can detect ahead of time, if you make a point of evaluating your swatch at a distance and in dim light.

If the project isn’t coming out at all as expected, try to figure out why. Is there a mistake in the instructions? Did you perhaps misinterpret or miss something you should have done? Check the publisher’s website and Ravelry.com for notes of any errors, or notes on what you find confusing. Contact the publisher and those on Ravelry who have completed this project to see whether they had a similar problem or can shed any light on your difficulties. If you bought the pattern and yarn at a local store, take it to the store to ask for advice.

One factor that is entirely out of your control, assuming you purchase yarn rather than spinning and dyeing your own, are inconsistencies and problems with the yarn itself. You may encounter annoyingly frequent knots, colors that rub off on your hands and clothes, inconsistencies in color, twist, and thickness, dyes that run, and shrinkage. The best way to avoid these problems is to be critically discerning when you buy yarn — look for problems in the balls and skeins. If you find any, decide whether you can live with them before you complete the purchase. Learn as much as you can about yarn by asking other knitters to share their experiences, checking Ravelry for comments, and reading the reviews at the online newsletter Knitter’s Review. (For websites, see Online References.)

While you should always try to purchase enough yarn for your project from one dye lot, this is not always possible. Skeins of handpainted or handdyed yarns may vary in color even if they are from the same batch.

If there is a difference in color, you can disguise the transition from one to another by alternating rows or rounds of each yarn. When you’re working circularly, just knit around once with one yarn, then knit around with the second yarn. When you change yarns, be careful not to twist them and not to pull the yarn so firmly that the last stitch made with it collapses to form a tight column of stitches that looks like a seam. Follow these guidelines, and the change of yarns at the beginning of the round will be unnoticeable.

When working flat, use a circular needle or two double-pointed needles so you can work from either end of the row. Knit across once with the first yarn, then slide the stitches back to the other end of the needle and knit across again with the second yarn. Turn your work and purl across with the first yarn, slide the knitting back to the other end of the needle, and purl across with the second yarn. Repeat these 4 rows to alternate the two yarns in stockinette stitch (see photos here).

If you are working a pattern stitch, try to alternate balls by working 2 pattern rows on the right side followed by 2 on the wrong side. If you find this confusing, just work 2 rows (right side, then wrong side) with one ball, followed by 2 rows with the other. You’re really just working 2-row stripes. Carry the yarns up the edge of the fabric loosely enough so that it stays stretchy.

It’s amazing how obvious a small variation in color can be in the knitted fabric.

Ready to purl across with the first yarn at right. You can see the tail from the new yarn, and the second strand of working yarn waiting at left.

In circular knitting, you can alternate the two skeins to blend two dye lots together. This is called helix knitting.

Whether you run out of yarn at an inconvenient moment or unexpectedly encounter a knot, you need to treat them the same way. The general rules are don’t tie a knot and don’t knit past a knot. Instead, cut the yarn when you run across a knot in your yarn, and proceed as if you’re starting a new ball of yarn. In a garment with a wrong side where the ends can be hidden later, just leave 4 to 6 inches of both ends dangling and weave them in later. If the resulting loose spot bothers you, go ahead and weave the ends in right away. See Weaving in Ends as You Go for instructions on how to weave in the ends as you knit.

If your garment is reversible or is openwork, it’s going to be more difficult to deal with the ends. Areas such as lapels, collars, and cuffs, which may be turned back, need to look good on both sides. My preference is to splice the yarn ends, which involves overlapping and twisting the two ends together, and then knitting past the join. Once it is knitted, it won’t come apart. Another approach is to use the “Russian join,” where the ends of the two yarns are looped together. This has two advantages: if you are changing colors, there’s a very neat transition because they don’t overlap, and you don’t need to worry about the join pulling apart before you have a chance to knit it. The Russian join is easiest to work in plied yarn. See Russian Join and Splicing Yarn for complete instructions.

Another option is hiding the ends while sewing them in, called duplicate stitch. When you come to the break in the yarn, overlap the two ends for about 8 to 10 inches and work just 1 stitch with the doubled yarn at the center of the overlap. You may be tempted to secure the new yarn by knitting a whole section of a row with the doubled strand, but this usually results in noticeably larger stitches. For this reason, it’s best to sew the ends in later. When you do, follow the path of the yarn exactly across the row for an inch or two before clipping the excess close to the fabric (see Duplicate Stitch, Purl side). For slippery yarn, you may use a tiny dab of Fray Check (available at fabric stores) to anchor the ends so they won’t pop out.

When working in lace or an eyelet pattern, if splicing the ends together won’t work for some reason, plan ahead to make your finishing simpler by positioning the break where it will be easier to sew in the ends. If there will be seams, place it at the beginning of a row, where the ends can later be woven in along the seam. If there are solid areas in the pattern, place it at or near one of these. You can then weave in the ends on the wrong side of the solid area, where they will be hidden.

Overlap the yarn at the break and knit just 1 stitch. On the following row, work the double strand as a single stitch.

Sometimes yarn will have a few quality problems. There may be an area where there is more twist or less twist than the rest of the ball or skein. Or there may be a section that’s noticeably thinner or thicker than the rest. Some yarns, of course, are meant to be thick and thin, slubbed, or garneted with contrasting colors. In other yarns, it’s simply a sign of poor quality control. Don’t just knit past occasional inconsistencies hoping they won’t show — they will! Treat them as recommended for knots (above): cut the yarn and discard the bad section.

If you have a whole skein that’s different from the rest of the yarn for your project, you may not be able to finish the project without using it. You can sometimes disguise inconsistencies by reserving this yarn for the borders, which are frequently knit at a different gauge and in a different pattern stitch from the rest of the garment. If this won’t work, you can also use the technique (described here for color variations) of alternating rows or rounds to integrate variations in yarn thickness or texture.

Actual mistakes in the knitting are, of course, something you’ll also have to cope with. This includes things like dropped stitches, extra stitches created by accident, mistakes in pattern stitches, and variations in gauge.

There are some you’ll absolutely need to address: Changes in gauge, for instance, will affect the ultimate utility of the garment — it may come out too big or too small to be comfortable. Losing or adding stitches inadvertently can also change the size of the garment, making it narrower or wider. Some mistakes impair the integrity of the fabric: Dropped stitches, if not secured, will continue to unravel, creating holes in the garment. A mistake that affects the stitch count will also make things more difficult for you when you get to future shaping in the garment, because you won’t be able to follow the instructions exactly; it may be possible to adjust for this, but it’s frustrating and will slow you down.

On the other hand, there are mistakes that are just aesthetic — they affect the way a garment looks, but don’t affect its fit or function. This would include things like accidentally working the same row of a pattern twice, substituting a knit for a purl in a textured pattern, or working the wrong color in stranded knitting. With these sorts of problems you have three choices: leave it as is, disguise it, or fix it. You’ll need to decide how much time you want to spend on these “nonessentials.” Unfortunately, these are sometimes the mistakes that are most visible and may drive you crazy. If you’re not sure, you can always leave the problem alone for now and plan to disguise or fix it later if it continues to bother you.

In the following sections I offer specific prescriptions for ways to cope with a wide variety of mistakes. Some fixes are easier and take less time than others. Before you jump in and start working on the more complex ones, take a little while to inspect your knitting carefully, diagnose and analyze what’s really wrong, then plan the best way to fix it. You may be very uncomfortable with some of the suggestions (like cutting or unraveling a section in the middle of the work and reknitting it). It can also be difficult to predict how long a specific solution will take; sometimes it’s actually quicker to just rip out and do it over than it is to spend hours correcting one small problem in the middle of the fabric.

In light of the annoyance that even aesthetic mistakes can cause, I have also provided some suggestions for detecting these mistakes as soon as possible, when they’re easier to fix.

If the mistake is of too great a magnitude or the suggested fix seems overwhelming to you, then the bottom line is that you can always unravel back to the point of the mistake and knit that section over. This can be a painful exercise if you’ve sweated over the section to be removed, but it’s really best to cut your losses and do it over if necessary in order to save the sweater. You may want to set it aside for a time, to contemplate whether this is really the only option and to consult with other knitters who may have found another way to cope with the same problem or who’ll offer moral and technical support during the process. It’s possible that letting the project age, like fine wine, will give your imagination time to come up with a novel solution.

Some mistakes elude even the most vigilant of knitters and are discovered after the garment is finished. If this happens to you, consult Fixing Mistakes in chapter 6 and The Elusive Pursuit of Perfection in chapter 8.

If you notice a dropped stitch within a row or two, it’s easy to hook it back up with a crochet hook. If the dropped stitch occurred more than a few rows earlier, however, the knitting will become very tight when you try to do this, so it’s better to unravel the whole piece back to the mistake to fix the problem. This may not be practical if you discover the dropped stitch much later. See Dropped Stitch, fixing in the appendix for how to hook up individual stitches and Capturing Dropped Stitches in chapter 6 for how to deal with dropped stitches discovered after binding off.

Unravel to the point where the stitch appeared. Work the extra yarn into the stitches on either side until the knitting looks even. If this will make a large loose area, it may be better to just decrease to get rid of the stitch when you discover it. Be sure to hide the decrease in an unobtrusive place. Usually there will be a hole where the stitch was created. Use a piece of yarn to close up the hole and weave in the ends on the back. (See Closing Up Holes in chapter 6.)

If the problem is limited to a few stitches, work the current row until you are above the mistake. To correct the previous row, unravel the one section that is a problem and rework it, then continue with the current row. For a mistake farther down in the knitting, unravel the stitches directly above it down to the problem. If there are just a few stitches to be corrected, use a crochet hook to work up the column of stitches correctly.

If there are more stitches, use short double-pointed needles the same size as those for your project to knit the unraveled area back up. These are especially convenient because they allow you to work from either end. In a complicated pattern, it may be least confusing to unravel and reknit one complete repeat of the pattern. Be sure to work each loose strand of yarn in order from bottom to top.

Try to keep the tension of the yarn consistent with the rest of the fabric, so that you don’t end up with a tight area at one side of the correction and a loose area at the other. If you do, simply slip the stitches one at a time to another needle, beginning at the loose end, tightening up the first stitches you come to and loosening up the later ones. When the correction has been completed, use the tip of a needle to tease the yarn from any loose areas into tighter ones.

If the problem is a whole row worked incorrectly, you can either rip your knitting back to that point and reknit it, or (if it’s a long way down) you can replace the row (see photos below). Snip 1 stitch in the row with the mistake. Make your cut about 6 stitches from the end of the row to ensure that you have a long enough tail at the end of the row to weave in after your correction is complete.

Unravel the whole row and slip knitting needles into the active stitches you’ve created above and below the row to be corrected. If it’s difficult to insert the size needle you’ve been using, then use slimmer needles. Using a yarn needle and Kitchener Stitch, replace the row correctly. You can use the unraveled yarn, but it won’t be quite long enough to complete the repair. It also may be difficult to work neatly if the yarn is kinky from having been knitted. You can wet it and lay it out flat to dry or steam it very lightly with a steam iron to straighten out the kinks. When there are only 4 to 6 inches of yarn left, start an additional piece of yarn to complete the join.

It can be very confusing to work Kitchener stitch in pattern. If there are any plain knit or purl rows in the pattern immediately above the mistake, snip and pick out the plain row, then unravel until the row with the mistake has been removed. Place the knitting on needles and rework the section you removed until you are ready to replace the plain row. Use Kitchener stitch to reinsert the plain row, which is much easier than trying to work Kitchener in pattern.

If there are no plain rows, you may want to practice Kitchener stitch in pattern on a swatch before you cut your knitting. Work the swatch in pattern, making one pattern row (the one you will need to duplicate later) in a contrasting color. Snip and remove the same pattern row from the swatch in a section above the contrasting row. While you are working Kitchener stitch, refer to the contrast-color row as a guide. If you find yourself making errors while doing this, practice the pattern row by working duplicate stitch along the contrasting row, following the path of the original yarn exactly.

In flat knitting, you can perfectly match pattern stitches and stripes at the seams when you join pieces together. One of the few drawbacks of circular knitting is that some patterns cannot be matched perfectly where the end of one round meets the beginning of the next. There are, however, techniques to disguise the jog or stair-step effect that is integral to circular knitting.

The “jog” is the place where the pattern is noticeably discontinuous when you begin a new round. When you change to the next round of a pattern stitch or a new color at the beginning of the round, it’s obvious where you made the change. The jog occurs because circular knitting is really a spiral, where each round lies above the previous one. Most of the tube doesn’t appear to be spiraling: only when there’s a discontinuity where one round ends and the next begins is its true structure apparent.

Attempting to correct errors can be very frustrating and time consuming, especially if your best efforts fail and you end up unraveling and starting over. If you realize that a particular pattern stitch is causing you difficulties, so that you need to correct more than a few mistakes or you find it impossible to correct the mistakes efficiently, take steps to prevent the mistakes from occurring and to make fixing them easier.

If you keep losing your place in the instructions, try one of these:

If you keep losing your place in the knitting on your needle, here are some suggestions:

If you find it difficult to make corrections without unraveling, especially if it’s almost impossible to get the stitches back on the needle afterward, place “lifelines” in your knitting periodically (see Lifeline in the appendix). Choose a pattern row you can recognize (for example, the first or last row of the pattern stitch), or perhaps the row immediately below the one on which you tend to make mistakes. Whenever you complete that row of your pattern, take a thin, smooth, strong thread or yarn and run it through all the stitches using a yarn needle. (I like to use crochet cotton.) Leave long tails at both ends of the lifeline so there’s no danger of any stitches falling off or the thread pulling out. If you need to backtrack, you can easily unravel back to the lifeline and slip your needle back in. In fact, you can first slip a needle into the fabric following the path of the lifeline, and then unravel down to it. This is most easily accomplished if you use a thinner needle. Work the stitches back onto the proper size needle on the first row you rework.

There are a variety of ways to make the jog less visible. Which you choose will depend on the situation.

The jog is most noticeable when the pattern is strongly horizontal.

Garter stitch

Purled ridges

Stripes

Make the total number of stitches an exact multiple of the pattern repeat when working a vertical pattern such as ribbing or cables, and the pattern will repeat seamlessly around.

K2, P2 ribbing in the round

Two-stitch colored stripes in the round

Patterns like Seed Stitch and the two-color checkerboard known as Salt and Pepper can be coaxed to repeat seamlessly by adjusting the number of stitches. If you work them on an even number of stitches, the jog is obvious; if you add or subtract 1 stitch to make the total odd, they repeat joglessly.

Working Seed Stitch on an even number of stitches (bottom) makes a noticeable jog. On an odd number of stitches (top) the pattern flows from round to round with no jog.

Like Seed Stitch, Salt and Pepper can be worked on an odd number of stitches (top) to eliminate the jog.

Patterns that reverse every other round can be made to appear seamless by adjusting the number of stitches to allow for half of a pattern repeat at the end of the round rather than a full repeat. This Broken Garter Stitch has a pattern repeat of 6 stitches. In the bottom half, an even multiple of 6 results in the end of round 1 running into the beginning of round 2, because 3 stitches on either side are all knitted or all purled. Decreasing 3 stitches to remove half a repeat means that the pattern always switches from knit to purl, or vice versa, at the end of the round, continuing the pattern seamlessly in the top half.

It’s not quite as easy to disguise the point where the end of one round meets the beginning of the next if the pattern is strongly horizontal.

Single pattern rounds (see photos below). If there is just one round to be dealt with, for example, one ridge of purl stitches or a round of eyelets, work the single round, then slip the first stitch of the following round. This will pull the first stitch of the pattern round up next to the last stitch (see Other Strategies for Avoiding the Jog with Strongly Horizontal Patterns).

Two-round patterns. For patterns that have a 2-round repeat, like garter stitch or alternating rounds of two colors, you can use Helix Knitting to hide the jog. For jogless garter stitch, use two balls of the same color — one for the knit rounds and one for the purl rounds. For alternating stripes just 1 round wide, use one ball of each color.

Patterns more than 2 rounds long. If you have a horizontal pattern more than 2 rounds long, the most efficient solution is to introduce seam stitches. These are a small number of stitches at the beginning of the round that are worked in stockinette, garter, or some other simple pattern stitch. They serve to separate the beginning and end of the round of more complex patterns so that their misalignment is not so noticeable. On sleeves, you will want just one set of seam stitches at the beginning/end of round, which will run along the inside of the sleeve. Make the bodies of sweaters and vests symmetrical by introducing a second set of seam stitches halfway around.

Single-round stripes, unless they lend themselves to helix knitting, can be made to look continuous only if you cut all the yarns at every color change. Leave 6-inch tails, long enough to sew with easily. When you have finished the project, turn it inside out and duplicate stitch these ends across the end of the round, directly behind the stitches of the same color. As you work, take care to adjust the tension of the stitches attached to the tails so they are the same size as their neighbors. The photos here show how to proceed step by step. (See Duplicate Stitch, Purl side in the appendix.)

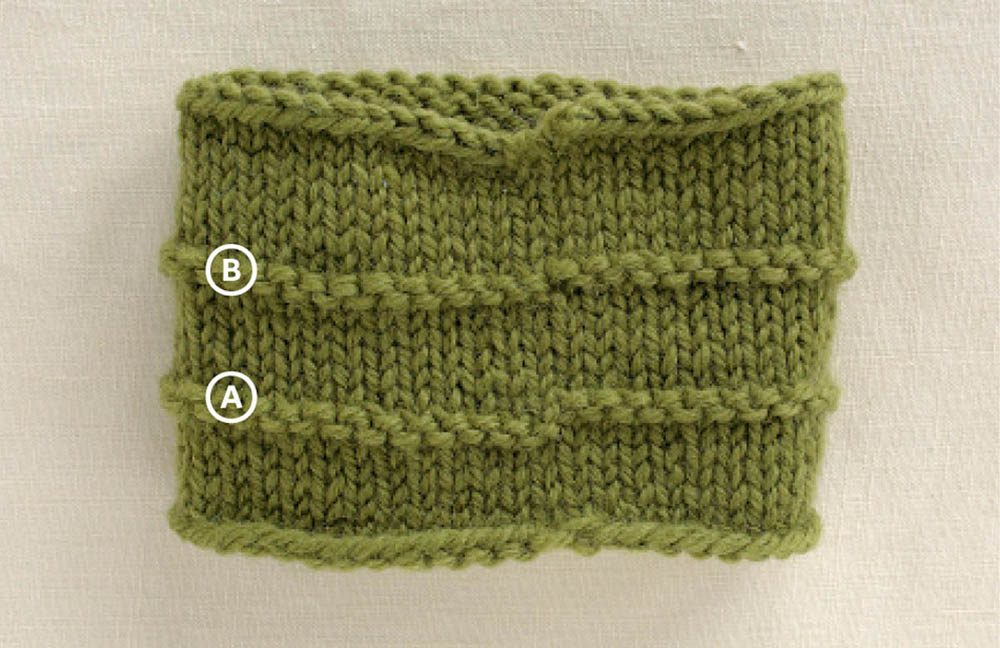

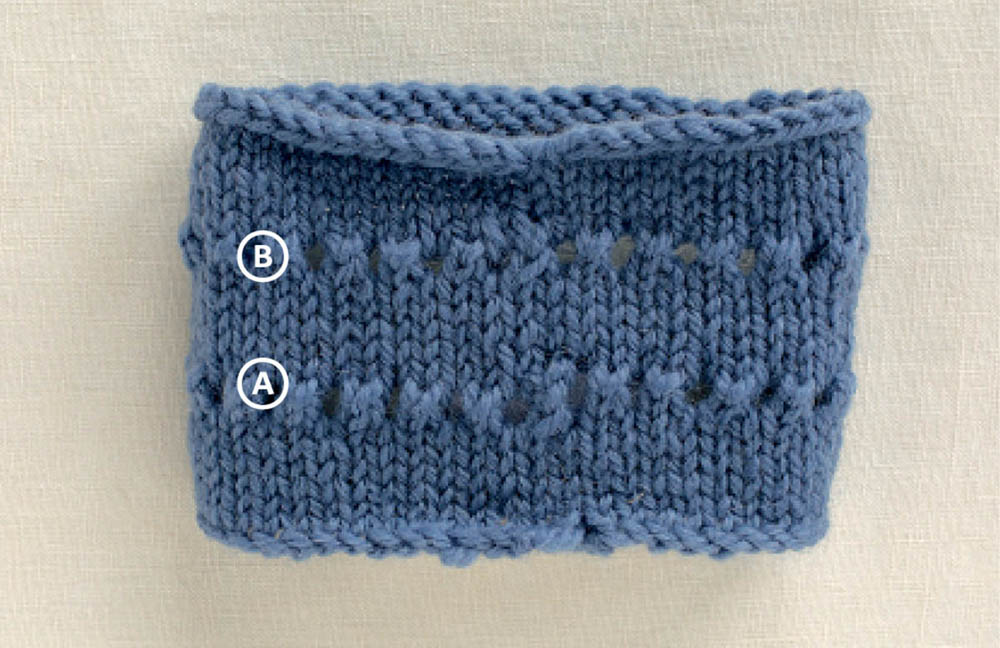

Single pattern rounds. In each of the two examples (above), nothing has been done to disguise the jog in the pattern round at the bottom A. At the top B, the jog has been made less obvious by slipping the first stitch of the following round.

Two-round patterns. At the left, garter stitch in helix knitting; at the right helix knitting makes the beginning/end of round disappear in one-round stripes.

Patterns more than 2 rounds long. Double garter stitch with and without seam stitches

Multi-round stripes. You can disguise the jog at the beginning and end of multi-round stripes by adding seam stitches as described in the hints here for Patterns More than 2 Rounds Long.

Cable at color change

One-stitch stripe at beginning/end of round in color not used

If you’re working in stockinette and don’t want to add seam stitches, but still want to smooth the transition between colors, the first step is to cut the ends of the yarn each time you change colors. Next, slip the first stitch of the second round of each color. Finally, duplicate stitch all the ends on the back to align the colors properly at the color changes, as described for Single-Round Stripes (below).

Leave ends long to work with when changing colors.

Shaping armholes, necklines, shoulders, and buttonholes will frequently require you to bind off or cast on while the work is still in progress.

When the instructions say to bind off 5 stitches at the beginning of the row, you need to actually work the 6th stitch so you can pass the 5th one over it, binding it off. You’ll always need to work 1 more stitch than the instructions call for in order to bind off the right number. Count the remaining stitches afterward to ensure that you’ve done it correctly.

The standard bind off will usually work just fine, either for shaping at the edge of a garment piece or to make an opening like a buttonhole. Just be sure you don’t bind off too tightly. If binding off tightly is a problem for you, try the Suspended Bind Off or one of the Decrease Bind Offs to loosen it up. If you’re working in stockinette or another pattern stitch with a tendency to curl, reduce the curling by binding off in K1, P1 ribbing.

Casting on at the edge of your work, over an opening like a buttonhole, or when starting a steek requires a single-strand cast on. The long-tail cast on, which requires two strands, won’t work in these situations (unless you’re working with two colors), so if this is the only cast on you know, you’ll need to learn another one. Choose one of the single-strand cast ons based on how you want the edge to behave.

The instructions for all of these single-strand cast ons are in the appendix.

Casting on or binding off in the middle of your work tends to leave a loose strand or a little hole at the beginning or end. To tighten it up, when you come to the loose strand on the next row or round, pick it up, twist it, and put it on the left needle as you would an M1 increase. Knit or purl this twisted stitch together with the next stitch, as your pattern dictates.

Or, when casting on, you can plan ahead and cast on 1 fewer stitch than specified. When you come to it on the next row, pick up the long strand between the stitches, twist it, and put it on the left needle. This provides the additional stitch needed, and no decreasing is necessary.

If a small hole remains, close it up using a nearby tail of yarn when you weave in the ends, or use a separate piece of yarn if there’s none in the neighborhood.

When you cast on or bind off mid-row, you are likely to get a small hole.

If you’re working the major garment pieces from the top down, whether in separate flat pieces or joined together in the round, you’ll usually continue through the bottom border on the body and the sleeves, and then bind off. The general advice for bottom borders given in Beginning with the Very Best Borders (chapter 2) also applies in this situation.

If you’re working a ribbing attached to stockinette stitch in a wool or wool-blend yarn, you’ll need to reduce the number of stitches by about 10 percent and move to a needle about two sizes smaller to produce a bottom border that pulls in a bit and retains its shape under tension. For other types of borders and in other combinations of base fabric and border stitches, you’ll need to adjust the number of stitches and the needle size so that the border is correctly proportioned to the body or sleeve.

Generally, the final bind off on shoulders should be firm to support the sweater. On the other hand, if you’re working top down, the bottom edge of the body and sleeves must be stretchy enough to be pulled on without straining the knitting (or the wearer), but appear neat and tidy when relaxed.

When choosing your bind off, think about how it needs to behave. Does it need to stretch or should it be firm and supportive? Should it be decorative? Does it need to maintain the pattern stitch or can it be plain? Do you want the bind-off chain to show along the edge, or would you prefer it to be more understated? The examples at right show a range of options for binding off, appropriate for a variety of situations.

The knitted version (worked knitting all the stitches, with the right side of the fabric facing you) makes a very prominent chain along the edge of the fabric. If you want your bind off to look this way, but need to work it from the wrong side of the fabric, just purl all the stitches instead of knitting.

The purled version (worked either from the wrong side, knitting all the stitches, or from the right side, purling all the stitches) makes a neat purled ridge at the edge of the fabric, perfect for making garter stitch look continuous all the way to the very end A, and makes a pleasant contrast to ribbing B.

The K1, P1 ribbed version of the basic bind off, which is made by alternately knitting and purling the stitches as you bind off, makes the signature chain of stitches lie along the very edge of the knitting, rather than on the knitted face of the fabric.

The standard bind off, where you knit 2 stitches and pass the first one worked over the second one and off the needle, will be the obvious choice for most situations. Even this very basic technique has several variations.

First consider how it will look.

Second, consider the tension of your bind off. Many knitters bind off a little too tightly. If you need a firm bind off, this can be helpful. On the other hand, if you need a bind off that is reasonably stretchy or must be loose enough not to pull in the edge of the fabric, try these alternative methods to see which works best for you. You may find that all of them are useful in different situations. Instructions for all are in the appendix.

Properly tensioned bind off (top) and tight bind off (bottom)

Sometimes you need a bind off that has more stretch than you can achieve with the standard bind off. It may be for an area that is around the outside of a curve, along the edge of a ruffle, or on an edge that needs to stretch enormously to prevent the yarn from breaking.

The bind offs described here are just the tip of the iceberg — there are so many ways to bind off that it helps to have a comprehensive reference on hand so you can choose just the right one.

Picot bind off creates a little bit of embellishment while adding stitches to the edge. This makes the edge longer, so it can stretch (see Picot Bind Off).

Yarnover bind off. I like to use this along the edge of ruffles, because it’s easily worked along long edges and requires no special knowledge. A regular bind off will act as a restraint, but the yarnover bind off is stretchy enough so the ruffle can ruffle to its full potential. This bind off can look a little messy when it’s relaxed, but it’s nice and neat when stretched (see Yarnover Bind Off).

Sewn bind off. I learned this bind off from Elizabeth Zimmermann’s Knitting Without Tears. It’s especially good when you don’t want the thicker edge that a bind-off chain makes. Because its tension depends entirely on how tightly or loosely you sew it, you can control it completely (see Sewn Bind Off).

Tubular bind off. This bind off (see Tubular Bind Off) is an exact match for tubular cast on, so you can make the beginning and ending edges of your garment match. It integrates perfectly with K1, P1 ribbing, and it wraps around the edge of the fabric without the bulky edge characteristic of the basic bind off.

Like the picot bind off, many embellishments at the bound-off edge are both decorative and add stitches that result in a stretchy edge. One exception to this is the I-cord bind off, which tends to have less stretch instead of more. These embellishments can be very feminine and frilly, or tailored and restrained.

A ruffle worked at the edge of the knitting is going to have plenty of stretch. To make a ruffle, all that’s required is to increase substantially, at least doubling the number of stitches, and then work until the ruffle is as deep as you like. Within that framework, you have lots of options.

Variations on ruffles are limitless (top to bottom): gradual increases using eyelets in stockinette stitch; increases only at the base of a garter stitch ruffle; doubling the stitches on every row in stockinette.

You can work a strip of noncurling knitting, plain or fancy, perpendicular to the main fabric, joining it to the base fabric at the end of every other row, and thus binding off. One side of this strip becomes the finished outer edge of your knitting, replacing the less stretchy chain of the standard bind off. If you decide to finish a garment with an applied edging, remember to allow for the width of the edging. For example, if you plan to add an edging that’s 2 inches wide, stop working 2 inches before you would normally bind off. You may want to put the stitches on pieces of yarn or spare circular needles, join the garment pieces together, and then work the edging seamlessly across all the pieces to bind them off. (General instructions for working applied edgings are in the appendix.)

Simple garter stitch edging

One repeat of Faggotting Rib is used here to create an openwork edging while binding off.

A simple lace edging

Necklines and shoulders often require a series of stepped bind offs for proper shaping. This type of shaping is sometimes used on armholes as well. Shoulder instructions will say something like, “Bind off 5 stitches at the beginning of the next 6 right-side rows.” At necklines and armholes, where a gradual curve is desirable, the instructions will read more like this: “Bind off 8 stitches at the beginning of the next right-side row. Bind off 4 stitches at the beginning of the next 2 right-side rows. Bind off 2 stitches at the beginning of the next 3 right-side rows,” and then instructions for decreasing 1 stitch at the edge for a number of rows will follow.

If you follow these instructions exactly, you’ll end up with an edge with pronounced corners or “stair steps” where each of the subsequent bind offs begin as in the photo below. These can be difficult to pick up stitches along or to seam neatly.

Shoulders, armholes, and necks shaped with a series of bind offs have pronounced stair steps.

To smooth the transition between each group of bound-off stitches, slip the first stitch of each bind off (except the first), instead of knitting it. For example, instead of following the instructions above for the shoulder shaping, do this:

To work the same shaping on the wrong side of stockinette, do this:

When the additional groups of bind offs begin with a slipped stitch or decrease, the sloped and curved edges are much smoother and easier to work with when finishing the sweater.

For an even smoother edge, you can incorporate slipped stitches on every row of the shaping, for example:

If the unworked slipped stitches make you uncomfortable, you can accomplish the same smoothing effect by working a decrease at the end of each row where no stitches are bound off, and at the beginning of the group of bound-off stitches on the following row. The two decreases take the place of 2 bound-off stitches in each group of 5, leaving only 3 stitches to actually bind off. Note that you can substitute ssk for skp, if you like.

To work the bind off on the right-side rows: Bind off 5 stitches at the beginning of the next right-side row, then work to the end of the row. *Work the next wrong-side row until 2 stitches remain, ssp. At the beginning of the following right-side row, skp, bind off 3, then work to the end of the row. Repeat from * until all stitches have been bound off.

To work the bind off on the wrong-side rows: Bind off 5 stitches in purl at the beginning of the next wrong-side row, then work to the end of the row. *Work the following right-side row until 2 stitches remain, K2tog. At the beginning of the next wrong-side row, P2tog, bind off 3 in purl, then work to the end of the row. Repeat from * until all stitches have been bound off.

Slipping the first stitch of the bind off and the last stitch of the row before each bind off makes an even smoother edge.

Hems can be created when you bind off, if an elastic border isn’t required. All you need to do is to continue knitting beyond where you want the fabric to end, then fold the additional length to the inside and secure it to the back of the fabric. A casing is just a hem big enough to run a drawstring or a piece of elastic through. This is another embellishment that offers several options:

Top to bottom: rolled hem, folded hem, and picot hem

Three ways to join (top to bottom): sewn without binding off, three-needle bind off, and picking up while binding off

You may want the bind off to prevent a piece of knitting from stretching or even to gather the edge. If you find yourself in this situation, there are several techniques you can employ, depending on how you want the edge to look.

You can make a firm edge by using a smaller needle while binding off. If this doesn’t make the edge short enough, try the 1-over-2 bind off. It’s worked similarly to the standard bind off, except that you start with 3 stitches instead of 2. Passing 1 stitch off the needle over the other 2 each time you bind off firmly gathers the edge (see Bind Offs.)

1-over-2 bind off results in a very firm gathered edge.

The I-cord bind off makes a cord along the edge as you bind off, providing support with a very slight stretch. This can be worked in the same or a contrasting color. If the I-cord needs to be either a little tighter or looser, you can easily adjust it by changing the size of the working needle (see I-cord Bind Off). The I-cord can also be made longer to fit the edge by working an occasional unattached round (work just the cord stitches with no decrease to bind off a stitch) or shorter by decreasing periodically in the main fabric stitches while joining the I-cord (which requires that you K2tog on the main fabric before passing the slipped stitch over to join the cord).

I-cord bind off in a contrasting color

When it’s going to be hidden in a seam or a picked-up border, it doesn’t really matter what the bind off looks like, so you might as well use the basic bind off. What is more important in these cases is how the hidden bind off behaves: make sure it’s elastic if it will need to stretch or firm if it’s required to support the garment.

When the bound-off edge will be seen, however, you should consider binding off in pattern. If you’ve been working a pattern stitch based on knits and purls, binding off in pattern is just a matter of continuing to work the knits and purls of the pattern stitch as you bind off. More complicated patterns, especially those that have a different number of stitches on different rows or that are much wider or narrower than plain old stockinette stitch, may require additional adjustments when binding off. Sometimes, you can get away with binding off on a plain row of the pattern. Other times, you may need to work increases, decreases, or short rows while binding off to avoid distorting the fabric.

Plain bind off on a chevron pattern like Razor Shell makes a slightly scalloped edge.

Including all the increases and decreases of the pattern row while you bind off creates an excellent exposed edge of points that mirrors the cast-on edge.

Row 4 of Old Shale is a plain knit row on the wrong side. Binding off on this row makes the pattern stitch look finished to the very edge, and working the bind off loosely allows the edge to ripple so that it matches the rest of the fabric.

If you need a straight edge for seaming or picking up a border, shift the decreases to the sections where increases occur in the pattern stitch when you work the final row and eliminate all the increases. This counteracts the curves and shortens the bound-off edge so it’s the same width as the rest of the fabric. Unfortunately, it also distorts the fabric so that the pattern is stretched out of shape at the top and must be blocked to encourage it to lie flat.

A more complicated solution, that makes the transition from a scalloped pattern to a straight edge without distortion, is to fill in the areas over the decreases with short rows, as well as decreasing to shorten the bound-off edge.

Cables pull the fabric in horizontally. Binding off without adjusting for this means that the edge will flare above each cable, especially the wide ones.

Decreasing above each cable as you bind off pulls the edge in. Decrease just 1 stitch on narrow cables, more on the wide ones.

Bind off on a row where you cross the cables to take the pattern all the way to the edge.

The traditional Fan Shell pattern is similar to Old Shale, except that, while all the yarnovers occur on a single row, the decreases happen gradually, so that the number of stitches varies from row to row. If you bind off on a row with the smallest number of stitches, you get a nice, straight edge.

This example was bound off in knitting on the wrong side on a row with the maximum number of stitches. It looks loose and messy.

Since the most noticeable pattern element is a ridge formed by 2 reverse stockinette rows, work until the first of these has been completed, then bind off on the following row in pattern to make the pattern continue to the edge of the fabric. Blocking is required to make the scalloped top edge neat.

The double wraps worked on every row of Horizontal Brioche cause the edge to ruffle if you bind off all those stitches normally.

To make the upper edge behave, work single wraps on the last row, reducing the stitches by half, then bind off.

When you’ve completed the front and the back, consider blocking those pieces, joining the shoulders, and adding the neck border before moving on to the sleeves. This will allow you to check the fit in the neck and shoulder area and to determine exactly how long the sleeves should be from cuff to armhole. (See The Conventional Approach to Flat Construction in chapter 2 for more details.) To get an even better idea of the fit, baste the side seams together and try on the body of the sweater.

You may want to block all the pieces as you complete them, just to check their actual measurements and to make finishing quicker and easier. Each piece can be drying while you knit the next. (See blocking methods in chapter 7.) This also gives you a chance to admire your work with justified pride.