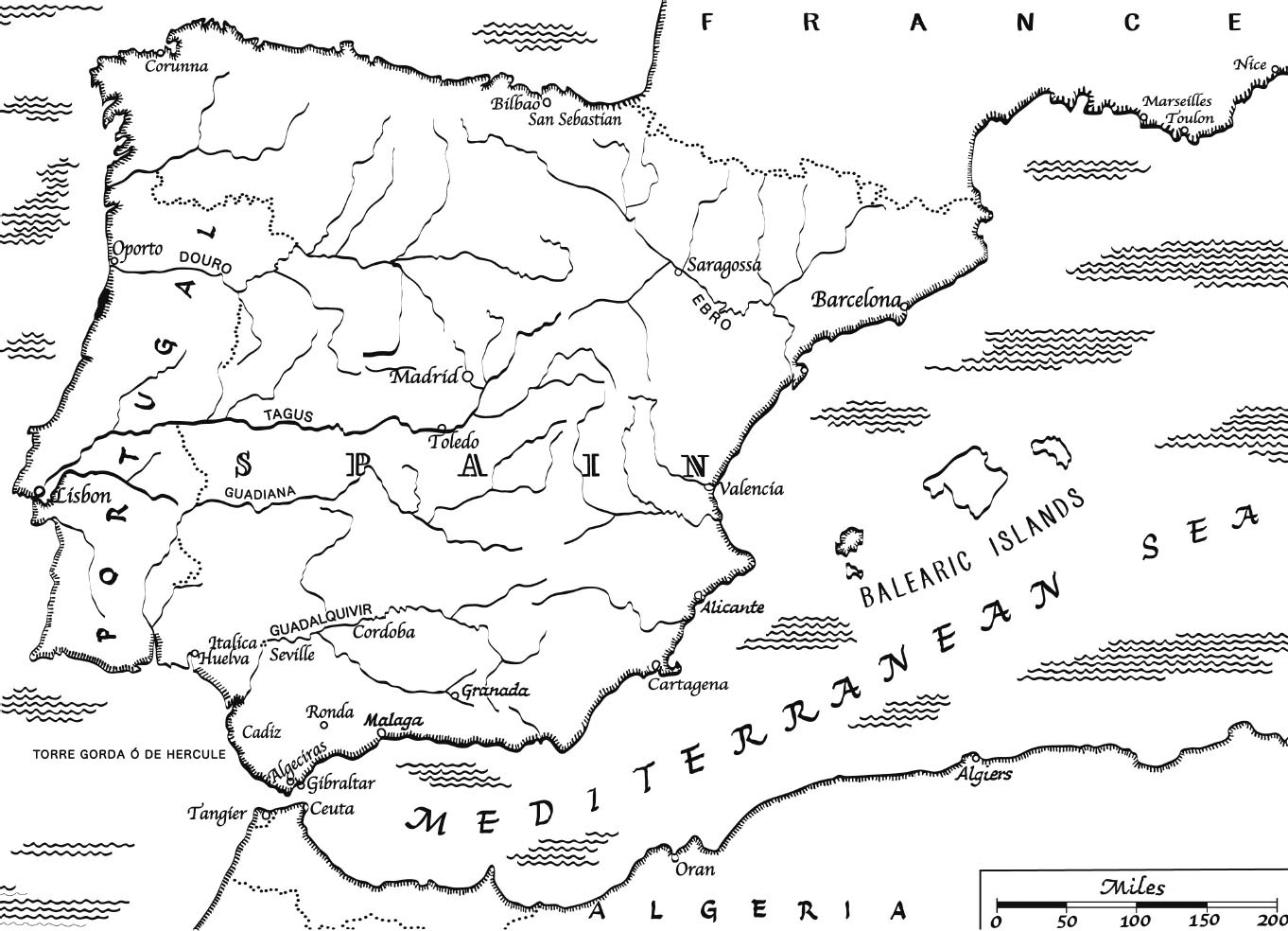

General map of the Iberian Peninsula.

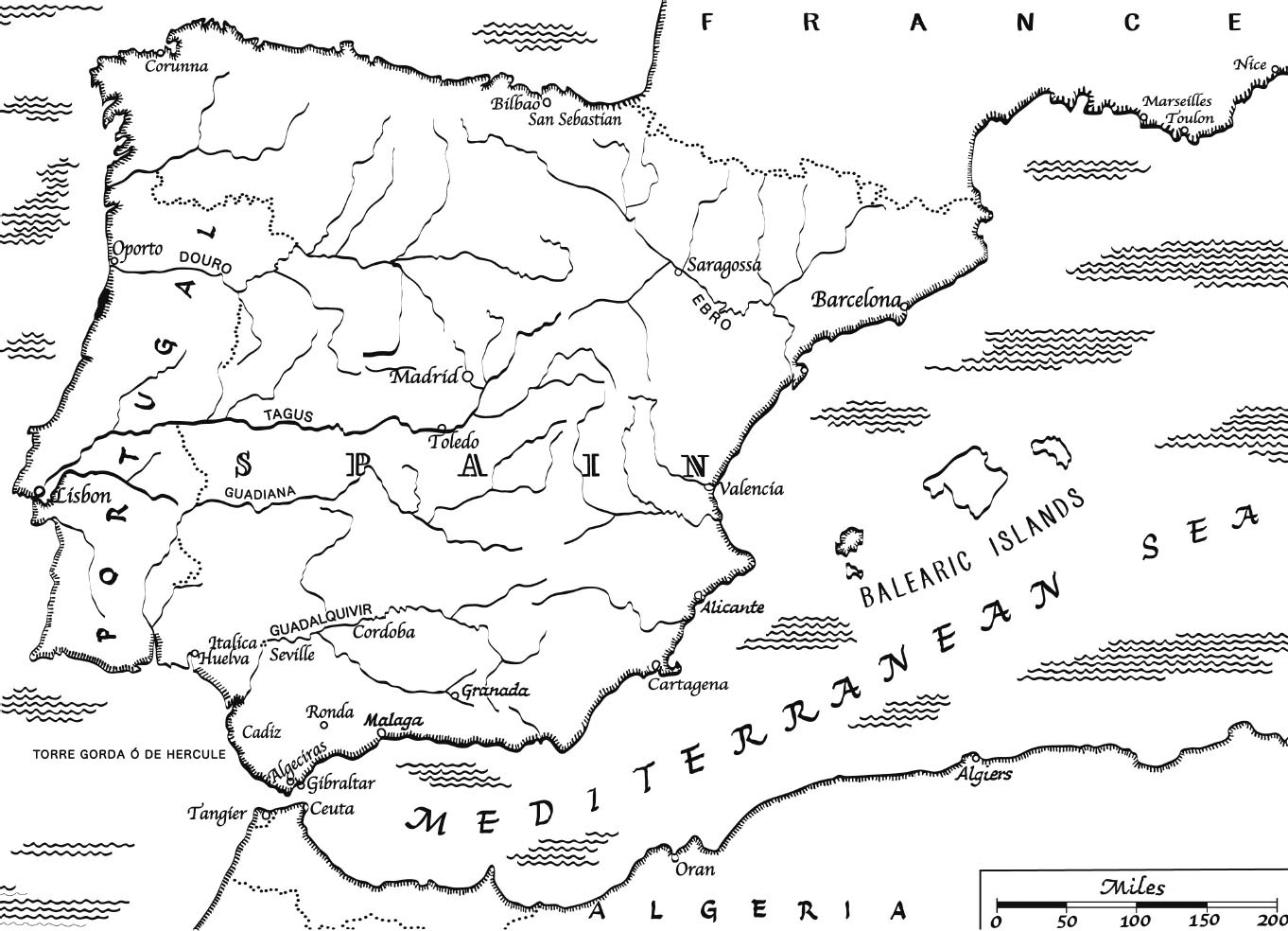

General map of the Iberian Peninsula.

Sir Samuel Hoare arrived in Lisbon on 30 May 1940 with his wife Lady Maud. He was sixty, balding and with a stooped bearing. He had a nervous disposition, though his smile was bright and infectious and he had a gregarious nature. He found the Portuguese capital bright with: ‘vivid colours of the jacarandas and the many exotic trees and shrubs, the radiant facades of the baroque churches and palaces, the silver setting of one of the worlds noblest rivers combined to make a superb prospect of external beauty.’1 Yet he was still depressed by the war news.

They stayed two nights at the embassy as guests of Sir Walford Selby, the ambassador for Portugal, who was an old-fashioned gentleman nearing retirement. David Eccles, a Scot, had managed the Central Mining and Investment Company before the war, specialising in Spanish railways. With the coming of hostilities he joined the Ministry of Economic Warfare, and was posted to Spain and Portugal to conduct economic warfare against the Axis. He arrived in Lisbon in April to take over the commercial side of Embassy business. He found Selby had ‘many delightful qualities’ but lacked the ‘stamina to be head of the mission’ during time of war. He did not have the confidence to deal with Salazar, the dictator of Portugal, so once Eccles was settled in he took over all dealings with him.2

Eccles was amazed at Hoare’s self-confidence and ignorance when he met him with Selby. Hoare, the new ambassador to Spain, told them he had only agreed to the appointment after pressure from Churchill and the King. He was confident he would soon have Franco eating out of his hand and he would quickly obtain a guarantee that Spain would remain neutral for the duration of the war. Then he expected to be moved on to be Viceroy of India. He estimated it would take no more than a few weeks, two months at the most, in Spain.

Selby, Eccles says, was ‘struck dumb’ by Hoare’s confident stance and it was left up to him to describe what he was likely to find in Spain. He told him that the people in the cities were starving, the secret police were ruthless, and they had heard from reliable sources that Franco was close to joining the war beside Hitler. On learning this, Hoare turned ‘pale’ and said he had been deceived and that his mission was hopeless and would therefore return to London. Eccles said that at the time ‘Selby and I rallied him as best we could …’3

The next day a telegram from London did not improve Hoare’s mood when it told him to: ‘Await further instructions before proceeding to Madrid …’ A day was spent waiting in Lisbon, whilst glued to the radio which was full of bad news.4

Eventually, they received the order to move on, and on 1 June they in Madrid. Flying over Portugal and Spain Hoare found Portugal ‘verdant and varied’ with an impressive ‘smiling landscape’ but the Spain of Estremadura and Castile was a country like many deserts he had flown over.5

Hoare remained fearful, and tried to hold the British Airways plane at Barajas airfield in case they had to leave in a hurry. He had even taken the precaution of carrying an automatic pistol and kept it with him night and day. Before leaving he had learnt how to use it in London. A bodyguard, who was a detective from Scotland Yard, also accompanied them. Arthur Yencken from the Embassy was there at Barajas to meet them. Sir Samuel knew him fairly well having played tennis with him before. He told Hoare that there had been orchestrated demonstrations at the Embassy to welcome him, and they were chanting ‘Gibraltar Esponal’.6 However by the time they had arrived into the city they had dispersed for siesta. The Embassy needed repairs, so for the first few weeks they stayed at the Ritz Hotel. It had been a hospital during the Spanish Civil War but had been newly restored to a high standard. For Hoare however it proved far from ideal as it was full of Abwehr (German Military Secret Service) agents. They watched him round the clock and his telephone was tapped. It was not the haven of rest that he had enjoyed in Lisbon. In the surrounding area, people were often beaten up by Falange thugs and the wife of a German diplomat jumped from the top floor of the hotel upon learning that her husband had been recalled to Germany. It was so intolerable that they started looking for a house.7

Sir Samuel was soon firing a barrage of letters back to Britain announcing his displeasure. He addressed one to Lord Beaverbrook on 6 June 1940: ‘If I had known the difficulties of this place. I never should have come here.’ To Neville Chamberlain on the same day: ‘Living in Madrid is like living in a besieged city.’ To Lord Halifax who had asked him to take the post he wrote three days later: ‘It seems futile to talk about all these things while the battle is going on.’ And on 11 June: ‘You cannot imagine how isolated I feel here.’ He also addressed a letter to Winston Churchill on 12 June: ‘At present I am not at all sure whether I shall be able to do any permanent good.’8

Immediate help was at hand to help him steer through the chaos. He had the excellent council of Military Attaché Brigadier Bill Tor and Naval Attaché Alan Hillgarth. Bill Tor helped him find a suitable house with his good knowledge of Madrid. The house was in the Castellana area within a brisk walk of the Embassy. The only disadvantage was that his next-door neighbour was the German Ambassador Baron von Stohrer.

Hillgarth was swift to advise Hoare, in writing, of his view of the state of the Embassy and its staff. He said they were a ‘defeatist’ bunch and needed ‘a drastic reorganisation’ and that the ‘Special Branch here is not allowed to be efficient.’9 After ten days in Madrid, Hoare wrote to Churchill to say that he had an ‘… excellent Naval Attaché in your friend Hillgarth’. He described him as a great ‘prop’.10 Hillgarth reported to DNI on security at the embassy where he found the staff lacking in the basics of security and likely too ‘careless or deliberate [with their] disclosure of information by members of staff, of whom there were at one time over 400 in the Embassy alone.’ He felt the need for a ‘full time security officer, but he must be at least First Secretary’s rank and should not be a career diplomat.’ Who he found was often ‘the most careless of all’.11

George Hugh Jocelyn Evans was born on 7 June 1899 at 121 Harley Street, the second son of the Surgeon Willmott Evans. He would, in 1926, change his name to Alan Hillgarth having first used the name as a nom de plume in his writing career. He was descended from Evan Evans, who was a Second Surgeon’s mate in the Royal Navy of the 18th century. A further seven generations of the Evans family became naval surgeons. Hugh, aged 12, was sent to Osborne College on the Isle of Wight, which was the preparatory school for the Royal Navy, and with his olive complexion and dark hair, he was dubbed ‘the little dago’.12

On the whole, he enjoyed life at Osborne. In the summer of 1913 the cadets took part in the Spithead Review aboard the battleship Bulwark which he found ‘absolutely topping’.13 In May 1914 he moved on to Britannia Royal Naval College at Dartmouth, to start the two-year course to make him a naval officer. However the outbreak of war changed that as all cadets were sent off to join fighting ships for the war effort. He joined the crew on the Cressy-Class armoured cruiser Bacchante which had been laid down in 1899 and would soon become obsolete. On the day war was declared, Cruiser Force C, of which Bacchante was a part, was on patrol in the North Sea. Afterwards, back in Deal, they learned they had sailed through a minefield where another cruiser had blown up and sank with the loss of 150 men.

Weeks later, Cruiser Force C provided a screen to intercept the movements of German ships during the battle of Heligoland Bight but was not directly engaged. Bacchante took on casualties and Hugh worked in the sick bay witnessing harrowing scenes. He told his mother that they brought the wounded and dead back to Chatham.14

By the end of 1914 Bacchante was in the Mediterranean. On 17 December Hugh sent home a photograph of himself from Gibraltar. In January, the ship was back in home waters whilst briefly docked at Devonport before heading back to the Mediterranean on convoy duties. Soon after, she joined the fleet in Egypt and arrived at Port Said in February 1915.15 After serving mainly in the Canal Zone, the Bacchante joined the Gallipoli campaign and arrived at the Allies, main naval base in Moudros on 12 April. The ship supported the landings at Gaba Tepe, a headland north of Cape Helles at the tip of the Gallipoli Peninsula. Her midshipmen, including Hugh, were in charge of the ship’s launches which were used to tow barges full of Anzac troops ashore.

Bacchante had a lucky escape. She had been on bombardment duties around Suvla Bay when she was relieved by HMS Triumph on 24 May. They had been warned that German U-boats were in the area. U-21 had left Wilhelmshaven on 25 April for the eastern Mediterranean and it reached Gallipoli on 25 May. At first the anti-submarine patrols, spotting her periscope, forced her away. A torpedo was fired at Vengeance but was spotted and avoiding action was taken. However, Commander Otto Hersing skilfully stalked the Triumph off Anzac Cove and at 12:25 U21 struck. Hersing fired torpedoes and one hit home. The destroyer Chelmer saved most of the crew on Triumph by putting her bows close into the stern of the sinking ship and a lot of men were able to escape, without getting wet, onto the Chelmer decks. However, seventy-five men were lost with Triumph.16 Hugh wrote to his mother on 31 May about the sinking of Triumph. He was not even sixteen at the time.

During the time the vessel was sinking and the boats were picking up survivors, the Turks and Germans were firing at them. ‘Shrapnel burst over us, and I should say that a fair percentage of the people who were killed were hit by shrapnel bullets while in the water. It was ghastly.’17

Much of the time with the Bacchante at Gallipoli, Hugh spent with the picket boats on various duties assisting the troops. He often visited the trenches, writing to his father in July that he was only fifteen yards from the Turkish lines in no-man’s-land. He said that dead bloated bodies gave off a sickening stench.18 The horrors of Gallipoli would haunt him for the rest of his life.

On 4 November he was transferred to the Beagle-Class torpedo-boat destroyer Wolverine, a much smaller vessel with a crew of 96 compared to the 750 on Bacchante. Wolverine also took him away from the carnage of Gallipoli and Captain Algy Boyle of the Bacchante who he felt ‘had a down’ on him.19 He joined his new ship in Malta where she was refitting and to his delight he found his new skipper was a ‘treasure’.20

In April 1916 Wolverine was bombarding Turkish coastal defences when it came under small arms fire and midshipman Evans was wounded. He was transferred to a hospital ship and, via Malta, sent home to England to recover.

Fit again he served on the battlecruiser Princess Royal, which was not a happy time as he was court marshalled for being asleep on duty but later acquitted.21 He was soon back in the Mediterranean on the sloop Lily. He started writing short stories about Gallipoli to pass the time. The first to be published appeared in Sketch magazine in July 1918. He stayed in the navy when the war ended, witnessing some of the events of the Russian Revolution and Civil War while serving in the cruiser Ceres in the Black Sea.22 These events were inspired his first novel The Princess and the Perjurer which was published by Chapman & Dodd in 1924.

The novel featured a scene where a ship arrives at Constantinople packed with White Russian refugees. There were soldiers, Cossacks, civilians, women and many children. There were wounded too, and those stricken with disease. There were even dead bodies of those who had perished with exhaustion. Others, unprotected from the rain and from the cold, without sanitary arrangements of any sort, some of them nearly naked, were unable to move: ‘Those who looked at me had in their eyes a dull, glazed stare, devoid of any emotion … They were of every class, I knew. Refugees from the Crimea might be princes or peasants. You could seldom tell by looking at them, so begrimed were they by filth, so far sunk in despair.’23

At the registrar’s office in Gibraltar, on 18 October 1921, Hugh married a nurse named Violet Mary Tapper. She was 27 and he was 22. The marriage only lasted a few weeks during which time they stayed at the Hotel Reina Cristina in Algeciras before she disappeared. She would go on to do this to other partners. Finally, in 1924, she divorced Hugh for adultery.24

In September 1922, after eight years of service, Hugh was placed on the retired list at his own request.25 However it is likely, like thousands of the others, he may have been a victim of the ‘Geddes Axe’ when in 1922–23 defence spending was slashed from £190 million to about £110 million. These economies were named after the chairman of the National Expenditure Committee Sir Eric Geddes. Thousands of servicemen were released prematurely while ex-servicemen suffered pension cuts.

Hugh did not have the burning ambition to stay in the navy. In 1923 he commuted his annual pension of £97 for a one-off lump sum of £1,370.26 He then took up his pen to become a writer and in the following years wrote and travelled a lot. In 1924 he obtained a master’s certificate from the Board of Trade which qualified him to command private vessels, but he had to get it replaced a year later after the motor yacht Constance caught fire and exploded in the Spanish port of Almeria, which was owned by Sir Cecil Harcourt Smith. Hugh had taken her from Monte Carlo bound for Gibraltar. There was talk of gun-running to Morocco.

Two years after leaving the navy he was calling himself Alan Hillgarth. His second novel The Passionate Trail was published in 1925 by Hutchinson. It was set in Egypt, and the hero Harry Chester foils a plot against British rule in Africa hatched by a Mad Mardi type of figure. He also falls in love with plenty of ‘exotic’ women. It seems as if he was clearly influenced by the likes of John Buchan and Rider Haggard.

On 3 September 1926 it was announced in The Times that he had changed his name to ‘Alan Hugh Hillgarth Evans’. In 1928, by deed poll, he dropped the Evans to become Alan Hugh Hillgarth.27

In 1923 he was in Ireland and he produced a 1,000-word report entitled ‘Bolshevism in Southern Ireland’. Who this was for remains unclear.28 He completed the novel The War Maker in 1925 published by Thomas Nelson & Sons. This was his third different publisher so clearly his ‘pot boilers’ were not a great success. This time, the hero Shaun McCarthy is offered five thousand pounds to run guns to Rif tribesmen in Morocco. This was probably influenced by his time in Ireland. Soon after, he went to Morocco.

After Morocco, Alan set off for the Americas sailing around South America in an ocean-going yacht. There are hints that he worked for the government as a King’s Messenger to deliver confidential documents to British Embassies and Consulates around the world.29 The cruise ended after several months at Palm Beach Florida where he stayed at the Yacht Club. Here he contributed several articles to sailing journals, including one to The Rudder on the Duke of York’s Trophy international race. What Price Paradise, his next book, published by Houghton Mifflin in 1929 was based on his time at Palm Beach and was the story of the rampant commercialism he found there. He also sold articles to the Daily Telegraph on smuggling alcohol during the Prohibition.

He returned to England in 1926 for a few days and worked on the London Underground during the General Strike. He was promoted to lieutenant commander in the Navy in 1927, which was unusual as he was still on the retired list. Could this possibly have been his reward for the work he had done for the Admiralty?

In 1928 Alan set off on a treasure hunt for lost gold to Sacambaya in the Bolivian Andes. It had been long rumoured that there was a colossal hoard of gold that had been hidden by Jesuit priests at or near the monastery of Plazuela in the high Andes. King Charles V of Spain had banned these priests from the New World for meddling in politics. Their wealth was based on the exploitation of gold mines in the area. Other earlier expeditions had found nothing. The 1928 undertaking was led by Dr Edgar Sanders, a Swiss national, who had led two previous reconnaissance trips to the area in 1925 and 1926. A company was set up for the far bigger 1928 trip, where members were expected to invest and take part. It is not known how much Alan invested.

They took masses of equipment with them which on the final leg up to Sacambaya had to be transported by mules. Alan was not impressed by the valley which he called: ‘a poisonous place – a dark, dirty valley shut in by hills.’ This valley was infested with biting insects and snakes, and it was boiling hot during the daytime and freezing at night.30 Having arrived in March it was a fiasco by November and after months of hard work they had found nothing. The enterprise was abandoned for the year. Alan never returned. In 1930 the company was wound up. Somehow Alan became the record keeper, keeping boxes of documents and a silver crucifix which had supposedly been found on one of the earlier trips. He kept in touch with Sanders. In later years stories abounded about other expeditions but they never found anything. One local guide, asked why no gold had been found replied: ‘It’s a gringo treasure.’31

During the Sacambaya fiasco, Alan was distracted by his scandalous love affair with Mary Hope-Morley, a dark-haired beauty, a married woman of thirty-two, and estranged from her husband the Hon Geoffrey Hope-Morley. Mary’s mother Winifred was the daughter of the 4th Earl of Carnarvon, a noted statesman, while her brother, the 5th Earl of Carnarvon, was the Egyptologist who discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings. Mary’s marriage to Geoffrey was dissolved on 3 December 1928 on the grounds of Mary’s adultery with Alan, and was cited as taking place at the Savoy Hotel. In January 1930 Alan and Mary were married and their son Jocelyn was born in September. The marriage freed Alan from financial worries as Mary, once Geoffrey had been granted his ‘decree nisi’, had settled to give her a generous allowance of £4000 a year. Soon after, What Price Paradise came out in America but sales were again poor.

The 150-foot twin-masted Dutch built schooner Blue Water was bought by Alan in 1929. He set off, complete with a crew and cook, for the Mediterranean, stopping at Majorca that summer as news broke of the Wall Street Crash.

In 1930 Alan and Mary purchased an old finca called ‘Son Torrella’ which was twelve miles inland from Palma. They were both enchanted by the old farm house and the island, and it was far cheaper in the circumstances to live in Spain. Over two years they restored the house, adding running water, bathrooms and electricity, whilst furniture was obtained locally along with a few pieces sourced from England. A large painting of Mary’s great-great-grandmother was delivered by the battlecruiser HMS Hood, by a group of petty officers who delivered it to Son Torrella.

Alan’s next novel, The Black Mountain, was based on his adventures to try to find gold at Sacambaya, and it was published in 1933 by Ivor Nicholson & Watson, his fifth publisher. The reviews were favourable and the film rights were sold in America for $5000 although the movie was never made. The book, like the others, did not sell well.

In December 1932 Alan was appointed the acting ‘Vice Consul’ in Palma by the British government. Though it was an unpaid post, he could at least be reimbursed for expenses.

Winston Churchill and his wife Clemmie visited Majorca in 1935 and stayed at Pollensa. Winston had come to the island to paint. They were invited to Son Torrella for lunch, which was an oasis of tranquillity. Sharing many common interests, including books and writing, Alan and Winston became friends, and it proved to be an enduring friendship.

Mary and Alan at this time enjoyed a golden period in their lives, yet around them Spain was in political turmoil. The country had fragmented and there were numerous political parties and labour unions which held seats in parliament. Governments formed and fell and soon it spiralled toward civil war. As Hugh Thomas puts it: ‘So now there was to spread over Spain a cloud of violence, in which the quarrels of several generations would find outlet. With communications difficult or non-existent, each town would find itself on its own, acting out its own drama, apparently in a vacuum. There were soon not two Spain’s, but two thousand.’32

That cloud of violence would soon find its way to Majorca. Alan, as the official British representative on the island, would find his diplomatic skills strained. In a dispatch to the Foreign Office, he observed that the average Spaniard on the whole loathed all foreigners ‘… and is so extremely individual that he loathes most of his fellow countrymen as well.’33

War broke out in July 1936 between the left-wing Republican government and the Nationalist Forces led by General Francisco Franco. Hillgarth had known Franco from the time the general had been in command of the Balearic Islands defences.

MI6 was involved in flying Franco to Spain. Major Hugh Pollard, sporting editor of the magazine Country Life, was an ardent Catholic Fascist sympathiser, and had been a police advisor during the Anglo-Irish war of 1919–1921. He arranged a chartered flight from Croydon Airport, using a de Havilland Dragon Rapide (G. ACYR), which flew the Spanish general from the Canary Islands to Morocco, which allowed Franco, ‘… to kick-start the armed challenge to the Republic.’34

The expatriate community may have thought briefly they were safe on Majorca since there had been no fighting on the island since the 15th century. However, Ibiza, fifty miles to the south, was invaded in early August. The Republicans quickly took that island and brutally stamped their authority there by attacking the church where twenty-one priests were killed and many churches torched.

The battlecruiser Repulse had already evacuated some 400 foreign nationals from Majorca. Most were British but there were also Germans, French and Americans. Alan had been on holiday with his family in England when hostilities broke out. He left Mary and Jocelyn behind and returned to Palma on the destroyer HMS Gipsy. On arriving, his main preoccupation was to deal with the expatriates who had refused to leave and he reported to the Foreign Office that there were ‘eighty-eight’ who refused.35

On 16 August a force of 2,500 men landed on Majorca from Republican warships. Four days later, Alan reported their attack had failed and that revenge was now being taken: ‘… Communists have been shot every night, but this cannot last long as there are not many left to shoot.’36

The British and French policy of non-intervention in Spain left Alan in an awkward position in the largely conservative Majorca. He had no time for the Communists and although he inclined toward the Nationalists he detested Fascism. During this time, Majorca was being built up as an Axis base with many German soldiers and Italian airmen arriving. The Axis bombers were within easy range of Valencia, Cartagena, and Barcelona, and there were bombing missions flying off every day soon after. Alan reported this to the FO. He observed that if the Republican cause were to succeed on the mainland, Majorca was likely to: ‘turn to some power for protection and in the present conditions that power would certainly be Italy.’37

Mussolini’s Italy supplied far more support to the Nationalists in Spain than Germany did. There were about 75,000 Italian military personnel serving in the country, and 4,300 would die compared to about 300 Germans killed, and 200 Soviets fighting on the Republican side.38

After a few months Mary returned to the island arriving on a British destroyer and they lived in a rented house in Palma. Once the threat of invasion had receded, and the Spanish Army had installed a telephone at Son Torrella, they returned to their farm. Alan was free to move about the island to check on the remaining expatriates. He became skilled at treading the thin line between the two sides, managing on one occasion to get the former Republican mayor of Palma, and his wife, off the island by smuggling them onto a British destroyer. Yet at the same time he developed a close working relationship with Vice Admiral Francisco Moreno Fernandez who commanded the Nationalist forces on the Balearic Islands. But as the war dragged on and became more savage, Alan wrote of the vice admiral that: ‘… it became increasingly difficult to get him to see reason.’39

The British government recognised the good work he had done and in April 1937 he was awarded an OBE. Robert Graves who had lived on Majorca but left before the war wrote to congratulate him, observing that he must ‘be getting tired of it by now’. Admiral Somerville, on the other hand, felt he should have received the CMG (Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George) for the ‘exacting work’ he had done.40 By the end of 1937 the number of British subjects on the island had risen to 137 as several returned to their homes despite the fact that Italian propaganda, Alan wrote, had made the British and Britain: ‘more unpopular here than she has ever been since we were last at war with Spain.’41

Alan worked tirelessly to save Spanish lives on both sides. He rescued Fernando Morenes y Curvajal, el Conde del Asalto, who had been captured and held by the Republicans and was awaiting execution on a prison ship in Barcelona harbour. Learning he would soon be shot, Alan bluffed his way into see him and smuggled him out dressed as a Royal Navy officer, going as far as to shave off his moustache.42 The two families became firm friends after that. Alan was instrumental in obtaining the surrender of Minorca to the Nationalists in 1939. HMS Devonshire took the delegation from Majorca to Port Mahon, and then the ship was used as a neutral meeting venue for the two sides. In spite of the Italians bombing the island while this was going on, much to the anger of the cruiser’s captain G. C. Muirhead-Gould, the surrender was concluded. The Devonshire then took 450 Republicans to Marseilles.

Duff Hart-Davis wrote of this:

As usual, Alan played down his own role in the proceedings, but his intervention was his single most important act during the whole war, and must have saved more lives than all the rest put together. It was his friendship with (Conde de) San Luis, his total command of Spanish, his steady nerve, his ability to commandeer a British warship, and his reputation as a diplomat with Spain’s best interests at heart, that made Minorca’s peaceful transfer of loyalty possible: by averting the threat of a Nationalist invasion, he prevented hundreds of deaths and wholesale destruction of property. For this he was remembered on the island with intense gratitude for the rest of his life, and for more than twenty years after his death.43

At the end of the war, Alan sent a memorandum to the FO that the Spanish were now concerned that a European War: ‘would force them into active participation on the side of the Axis, a thing they do not want …’ But would find difficult to avoid believing Germany ‘is invincible’.44

The Spanish Civil War had cost Alan not only financially but in time away from his writing and his family. Admiral Sir Dudley Pound Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean during most of the civil war recommended that Alan should be promoted to Commander on the retired list as recognition for his efforts over the three years. The Admiralty turned it down as he had not completed enough service on the active list.

When Admiral Godfrey became DNI, he addressed the glaring omission of there being no resident naval attaché in Madrid. The Paris naval attaché was meant to cover Spain, which was a wholly inadequate arrangement. By June 1939 he had convinced the Treasury and Foreign Office to appoint an assistant to the NA in Paris to reside in Madrid. This was just the first step. The next step was to transfer the post to Lisbon, before finally upgrading to the naval attaché in Madrid.45 Godfrey and Alan met in 1938 when the Repulse came to Majorca. They found they had much in common having both served during the Gallipoli Campaign as junior officers. Alan proved a great help. He had a mission to visit the British Legation at Caldetas near Barcelona, and was worried his ship might get caught up in Italian air raids. However Alan, through his contacts within the Spanish Command and Italian Air Force, obtained the undertaking promise that no raids would be conducted in the area during the Repulse visit. Godfrey called it an outstanding feat ‘in practical diplomacy’.46 In August 1939 Alan took up the post of NA in Madrid and was recalled to the navy’s active list.

David Eccles arrived in the Spanish capital in November and found there was ‘a great deal of damage’ from the civil war. He was soon at work and wrote to his wife Sybil:

We had our first meeting today. It is curious how difficult it is to realise that England is at war and that we must bend our efforts to winning as soon as possible. If we were not at war we could certainly give some very welcome and very valuable assistance to the reconstruction of this country. As it is it will be more difficult, but we shall manage something.47

The task facing the new naval attaché to Madrid was daunting. The British Ambassador, Sir Maurice Peterson, had treated his role casually and chose to reside in Paris. There had been no NA in Madrid for sixteen years. His predecessors had done little in the country and, as Alan wrote: ‘[had] no knowledge of the place or people and no influence whatever.’48