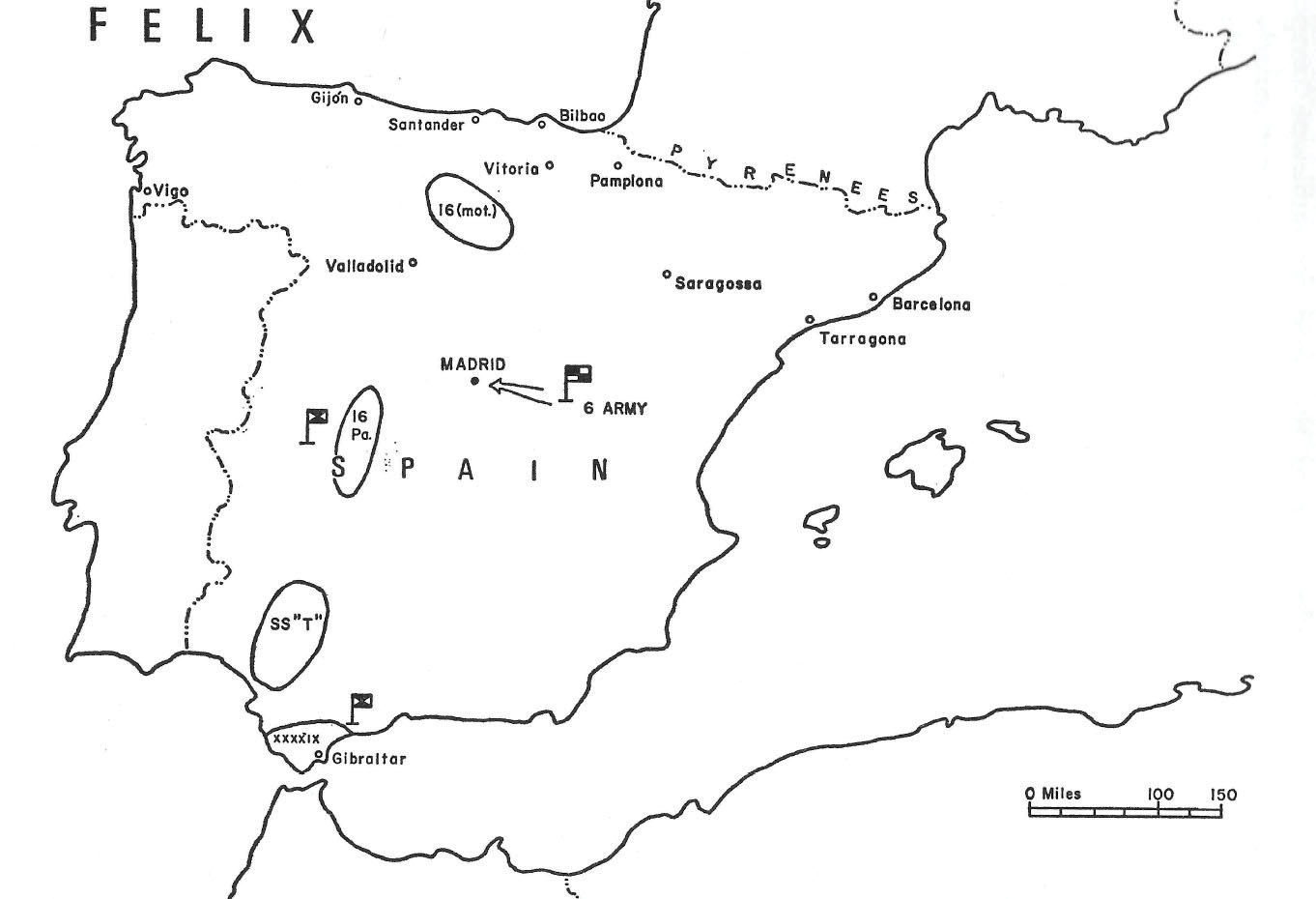

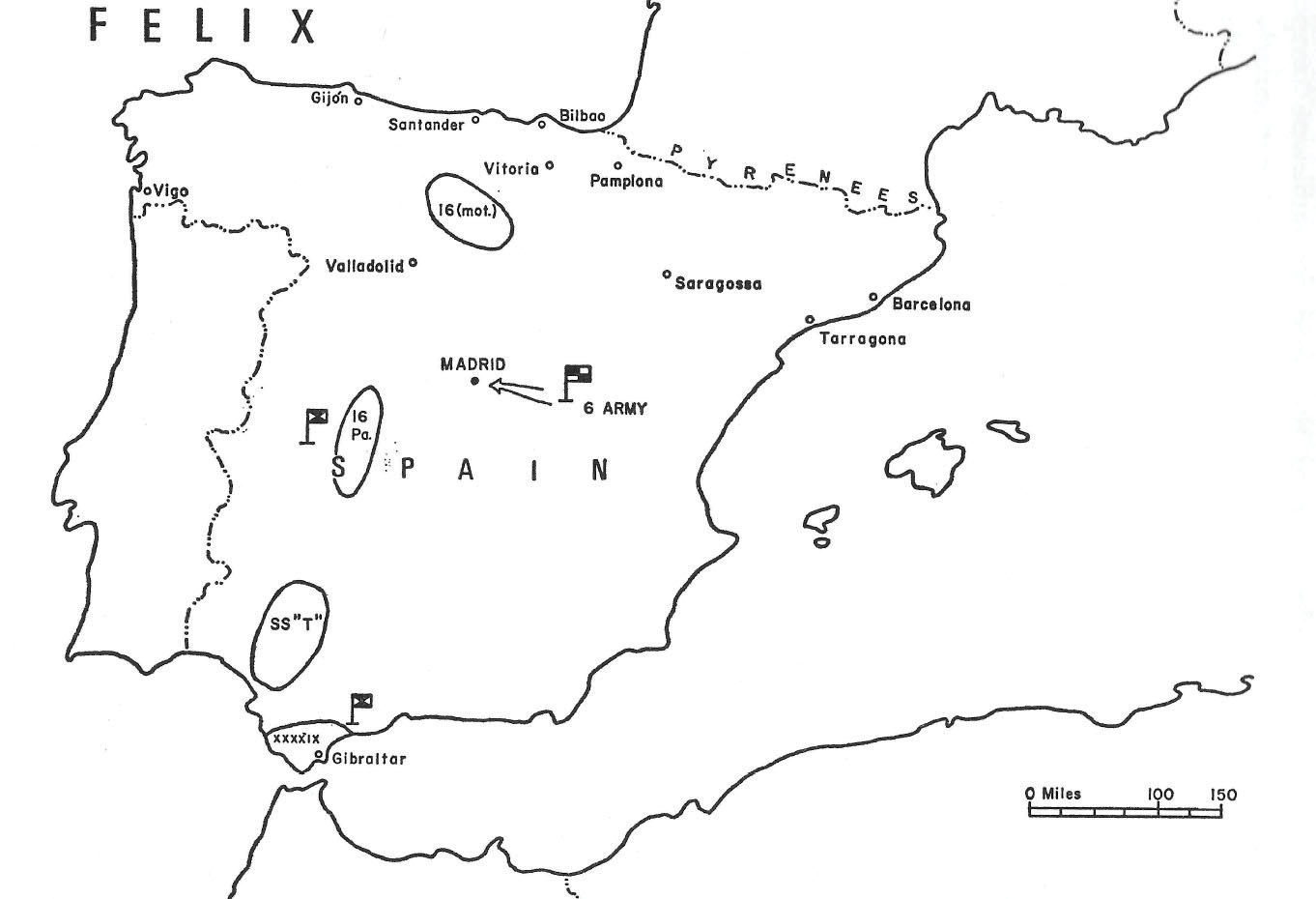

Operation Felix plan 1940–41.

Ian Fleming flew back from Tangier, having done as much as he could, via Lisbon to London. He wrote to Hillgarth thanking him and Mary for their hospitality and kindness to him and praising Alan’s excellent work as naval attaché in Madrid. NI was fortunate to have such a strong team ‘in our last European strong hold’ resulting in the ‘great contribution you are all making to winning the war.’ Later in the same letter he turned to Golden Eye:

4/ You will by now have a signal about receiving Golden Eye messages. Mason Macfarlane has no objection, and C. N. S. (Commander Naval Station) is about to give his decision, which I have no doubt will be favourable.

He finished with Portugal:

7/ I discussed the inclusion of Portugal in Golden Eye on my way through Lisbon, and got the Naval Attaché’s reaction on a very general plane. This has been put up to the Planners, and I have no doubt that the answer will be “Yes,” and that Owen will be instructed to go down to Gibraltar to report to the delegation.1

Back in England he may not have felt as optimistic for by that time the Battle of Britain was raging and the preparations to defeat the threatened invasion seemed insufficient. On 12 August the Luftwaffe struck its first hard blows at the RAF airfields and radar stations in southern England. For a week they launched heavy raids, on 15 August flying 1,786 sorties before cloudy weather intervened.2

A month earlier Adolf Hitler had issued his directive No 16: ‘As England in spite of the hopelessness of her military position, has so far shown herself unwilling to come to any compromise, I have decided to begin to prepare for, and if necessary to carry out, an invasion of England.’3 In the weeks prior to issuing this order Hitler faced several dilemmas. The first and most pressing was Britain’s refusal to make peace. For weeks he had savoured the glory of victory and soaked up the acclaim of his generals that he was a military genius. However the British attack on the French Fleet at Mers-el-Kebir on 3 July had shaken him from his dream of a short war. It was clear that Britain intended to fight on.

He faced five options, none of which were very attractive. The first was Operation Sealion, which was a planned cross-channel invasion of England that would be a risky undertaking. Hitler was not averse to gambling but he feared such operations. Perhaps subconsciously a seaborne invasion worried him because he could not swim and often said: ‘On land I am a hero, on the water I am a coward.’4

The second option was an air assault. However the Luftwaffe was not designed to be an independent strategic air force and had no four-engine heavy bombers and those it did have carried too light a bomb load and were lightly armed. The third was a siege of the British Isles but the German navy had too few submarines. The fourth was a Mediterranean strategy but that might not work, as it was unlikely to be decisive alone. The fifth, a grand strategic alliance against the British Empire but the prospective allies to achieve this were seen as unreliable, especially Soviet Russia who he saw as an enemy.5

For most of July he continued to be frustrated and lacked drive. However preparations for the cross-channel invasion got under way. In his mind he likely saw it as another gamble but was it a risk he was willing to take, or was it just a bluff? During this time there was no sign of any interest in Spain.

It was General Alfred Jodl, Chief of the operations Staff, ‘a major figure among the small coterie of soldiers and politicians surrounding Hitler’6 who focussed the Fuhrer’s mind on Spain. On 30 June he presented a six page survey on the direction of the war. He was not in favour of a cross-channel invasion in 1940 preferring a siege to bring Britain to its knees. After that he briefly mentioned the ‘indirect approach’ through attacks on the British Empire, requiring the support of other nations which included Spain. With their good links with the Franco government, operations against Gibraltar and through Spanish Morocco to the Suez Canal could be considered.7

On the following day Hitler met Dino Alfieri the Italian Ambassador to Germany for a ‘brief chat’.8 Three days later Alfieri reported on the meeting to Count Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini’s son-in-law and Foreign Minister, who wrote in his diary:

Alfieri has reported on the conference with Hitler. I am convinced that there is something brewing in that fellow’s mind, and that certainly no new decision has been taken. There is no longer that impressive tone of assurance that surfaced when Hitler spoke of breaking through the Maginot Line. Now he is considering many alternatives, and is raising doubts which account for his restlessness. Meanwhile, he doesn’t answer Mussolini’s offer to send men and planes to participate in an attack on England. On the other hand, he offers us air force assistance to bomb the Suez Canal. Obviously he does not trust us that much.9

On 7 July Hitler was in Berlin for the French victory celebration. Count Ciano was there for the same reason and spoke with him and received a ‘warm reception’ from the Fuhrer. As to the invasion of England he was told that ‘the final decision has not been reached’ but that he appeared ‘calm and reserved’.10 Ciano later spoke with Field Marshal Keitel at some length. He felt that a strike at Gibraltar was the best way of subduing Britain, whereas the cross-channel attack had too many uncertainties.11

Unable to make his mind up, Hitler went to his mountain retreat the Berghof. On 21 July he met with Admiral Erich Raeder to review the alternatives again. He reiterated his dislike of Sealion with Britain’s control of the sea.

On 10 July Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel asked Admiral Wilhelm Canaris to lead a team to Spain to assess the feasibility of taking Gibraltar as Canaris was considered the German ‘expert’ on the country. Within ten days, Canaris had set off for Spain.12 The team consisted of Colonel Hans Piekenbrock, a competent professional soldier and head of Section 1 of the Abwehr, Secret Intelligence abroad. He was much taller than Canaris, his chief, who only stood at about five feet four inches. Piekenbrock had a good sense of humour and the two men often travelled together. Colonel Hans Mikosch, another member of the team, was an engineer and Major Wolfgang Largkau represented the artillery. Captain Rudolf Witzig was an assault engineer who had taken part in the capture of the Belgian forts at Eben Emael, and the last member was a captain from a parachute regiment.13 On 22 July they all travelled through Spain by different routes with false passports and in civilian clothing.

As soon as Canaris was in Spain he felt the country lift his spirit with its ‘constant exhilaration’. Fluent in Spanish and, in the right dialects, he could easily pass for a local ‘whose home these worn Sierras, windowless churches and mud-built villages were.’14 He enjoyed the food and wine at small wayside inns, and liked driving the dusty hard roads in powerful cars – such as the American Buicks or Packards. He had first visited the country during World War I.

Wilhelm Franz Canaris was 53 in 1940. He was born in the small mining town of Aplerbeck near Dortmund Westphalia, and was the son of the wealthy industrialist Carl Canaris. He joined the Imperial Navy Academy at Kiel on 1 April 1905, where a military infantry course was followed by nine months of naval training. A fellow cadet found him ‘slow to speak but quick to listen’.15

By the time World War I started, Canaris was serving in the South Atlantic on the light cruiser SMS Dresden as an intelligence officer. He soon gained a reputation for being reliable and competent. The Dresden had been part of Admiral Maximilian Graf von Spee’s squadron that had sunk the British Pacific Fleet at Coronel, with the loss of two armoured cruisers and nearly 1,600 men. For three months the Germans had been masters of the South Pacific before the powerful British ships closed in and they decided to flee via the south Atlantic. The British Fleet caught up with Spee’s ships off the Falkland Islands and, on 8 December 1914, the battle cruisers Inflexible and Invincible sent them to the bottom of the Atlantic. Only Dresden escaped due to its superior speed.

For several months Dresden played a game of hide-and-seek with the British, much to the chagrin of the Admiralty in London. Canaris played a major role in arranging clandestine meetings with supply ships. However, the Dresden was finally cornered near Chile by HMS Glasgow which opened fire despite both ships being in neutral waters.

In Chile the crew of the Dresden faced internment for the rest of the war. However many of the crew managed to escape, the first of which was Canaris, who could speak Chilean Spanish with no foreign accent. Olga Krouse entertained several of the Dresden’s officers at her parent’s villa and remembered Canaris: ‘He had dark hair and skin and was well educated in manner. He did not look German. Neither was he good-looking, but he had an attractive personality.’16 She witnessed the first part of his escape after her brother-in-law supplied him with money and a forged passport. Watching from a window, she saw Canaris leave ‘dressed as a peddler wearing clothes and a cap which seemed to cover his face almost entirely. He had exchanged his heavy German suitcase for a canvas bag.’17

Canaris got to the capital Santiago and obtained a Chilean passport from the German Embassy in the name of Reed Rosas. By Christmas he had crossed the Andes by donkey and on foot but contracted malaria. In Buenos Aires he took time to recover and was helped by the local German community. Fit again, he took the Dutch steamer Frisa back to Europe.

Canaris got on well with the English passengers on board the Frisa, becoming a popular player at the bridge tables. The ship’s first port of call was Plymouth, but no suspicion had been cast on Senor Rosas. Canaris disembarked at Rotterdam and from there, still using his Chilean passport, crossed the border into Germany.

These exploits cemented Canaris’s name within the German Navy. His name would also have come across the desk of Commander Mansfield Cumming ‘C’ of the SIS, and maybe even brought to the attention of Winston Churchill at the Admiralty for the first time.

Back in Berlin he was awarded the Knight’s Cross in September 1915, and shortly after joined the ND (Geheime Nachrichtendienst) the security intelligence service. Early the next year he was sent to Madrid, an ideal appointment with his perfect Spanish, to provide accurate intelligence on Allied shipping movements. Again he used his pseudonym of the Chilean Senor Reed Rosas. He took a flat not far from the German Embassy, a place he never visited as it was under constant observation by Allied agents. However in his flat he met with Hans von Krohn the naval intelligence officer from the embassy and Eberhard von Stohrer, a first secretary, to discuss the Allied ship movements. At the time, few knew Canaris other than by his code-name ‘Kika’ meaning ‘peeper’.18

‘Kika’ soon built up a network of agents and informants across all the main Spanish ports to gather information on Allied shipping. He obtained the services of several Spaniards who were day workers in the British colony of Gibraltar. Intelligence from these sources was given to Krohn who then signalled the Austrian naval base at Cattoro where it was passed to the U-boats. The submarines at the time could not be re-supplied beyond their Adriatic bases which restricted their operational range, a shortcoming Canaris set about changing.

He cultivated relationships with several wealthy Spanish businessmen and financiers like the man he knew as ‘Ullmann’ who came from a German Jewish family who had migrated to Spain, and came to play an important part in Canaris’s life. The Spanish industrialist Horacio Echevarrieta was another, one of the richest men in Spain, with interests in banks, newspapers, and shipping. Both these men were more interested in making money rather than supporting Germany.

With a large budget Canaris was able to buy the services of Spanish ships to resupply U-boats at sea. The ships were commissioned by Reed Rosas for use in South America, but trials took them to the bay of Cadiz where at night they rendezvoused with submarines to supply fuel and provisions.

Cummings, the head of the SIS, realised the importance of monitoring U-boat movements around Spain, and agreed early in the war to leave control of the service on the Iberian Peninsula to the head of the Naval Intelligence Division Captain William Reginald Hall, known as ‘Blinker’, from his constant blinking. Hall sent his personal assistant Dick Herschell to Spain to set up a permanent operation there. Lord Herschell was a German linguist who had been working in Room 40, the cryptanalysis section at the Admiralty, working from the Ripley building at Whitehall. Herschell had good connections in the country being a personal friend of King Alfonso XIII and his wife Queen Victoria Eugenie. These contacts proved invaluable, far outstripping those of the German Ambassador Prince Ratibor.19

To control the operation in Spain, Hall appointed A. E. W. Mason, an author who had once been a Liberal MP. He was a keen mountaineer and yachtsman and, although 49, he had managed to enlist in the Manchester Regiment by the ruse of reducing his age by twelve years. Hall had Mason transfer to the Royal Marines. Around this time Reed Rosas had come to the attention of the British who sent the Captain Stewart Menzies to ‘Kill or Capture’ Canaris. However Canaris got ‘wind of’ the British interest in him and he promptly disappeared.20 Canaris left Spain in February 1917. It was during this first period in the country that he met the young Spanish Army Officer, Francisco Franco, who was as enigmatic as Canaris himself.

Suffering from recurring malaria, and still using his Chilean passport, Canaris headed for Germany by train. However he was arrested by Italian police at Genoa, who had been tipped off by French Intelligence that Reed Rosas was a German spy. This information was gained from a source within the German Embassy in Madrid that had heard the name there.

Clearly ill and claiming he was en route to a Swiss clinic, Canaris talked himself out of a Genoan jail. But the border guards at Domodossola were not fooled and removed him from the train on which he had been a passenger and locked him up. He was arrested with a priest and his subsequent release may have been due to Vatican pressure.21

He was put onto a ship bound for Marseille, where the Italians hoped the French authorities would deal with the Chilean-German, whoever he was. But Canaris’s luck held. The ship’s captain was Spanish and he bribed him not to dock at Marseille, or any other French port. Instead he was put ashore in Cartagena, still feverish with malaria. By March he was back in Madrid, where he applied for active service. Hans von Krohn told him he would have to remain in Spain for the time being. He spent another six months building up more contacts. However neither he nor Krohn knew his spy rings had already been compromised by Room 40 breaking the German ciphers.

Blinker Hall had taken over control of some aspects of Room 40’s work and put his energy behind not merely collecting naval intelligence but also into systematic diplomatic code breaking. The key to this was the amount of wireless traffic between Berlin and Madrid.22 When examined, it was found a high proportion were messages from and to military and naval attachés. Also some of these messages were still being coded in the Verkehrsbuch (VB) codebook which had been obtained in 1914.

Madrid was of great importance to Germany as its centre of trade and communications with the rest of the world, and controlled the biggest espionage network outside of Germany. This was a great coup for Hall and his team which led to a prolific source of intelligence.23

These intercepts were very detailed and revealed German espionage activities in Spain down to individual agents and spies. For example in June 1916, Berlin informed the Madrid Embassy that agent ‘Arnold’ was on his way to help organise the destruction of ships transporting iron ore from Spain to Britain. An embassy official questioned this as ore was always transported by Spanish ships, and did this mean the ban on attacking neutral ships had been lifted?24

Canaris finally left Spain in October 1917 and was picked up by U-35. The businessman Juan March had learnt of the operation through his huge network of workers and agents. His ships were known to supply U-boats with fuel and supplies. Once the operation had been completed however they promptly supplied the British with the locations and routes the submarines were using in the Mediterranean, often ending with the destruction of the U-boat supplied. He was more than happy to be paid by both sides but soon became aware that the Allies were the better bet. With information from March, two French Submarines, the Topaze and Opale, were supposed to ambush U-35 but they bungled the mission and Canaris managed to reach the U-boat in a fishing smack and had to scramble onto the casing as the submarine prepared to dive, and fled for the Adriatic.25

Back in Germany Canaris joined the Submarine service in Kiel. It was there he met Erika Waag, the woman he would marry after the war. After completing training he was posted to Pola and joined U-34 as second in command. The submarine took a heavy toll on British merchantmen in the Mediterranean.

The entry of the United States into the war tipped the strategic balance decisively against Germany. In October 1918 all U-boats in the Mediterranean were ordered home. By that time Canaris had risen to command his own submarine, U-128. He reached Kiel on 8 November to find the ships of the High Seas Fleet gripped by revolution and mutiny and flying red flags. Three days later the war ended, as did the world Canaris had been brought up in. The navy he loved suffered a complete breakdown in discipline. Yet the officer corps soon rallied to undermine communist attempts to control the navy. Canaris, although no longer a field agent, was quick to act during the communist attempt to take over Germany during 1918–21, aiding the assassins of the communist leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. The German communist threat ended after the failure of the uprising in 1923.

In the 1920s Canaris’s linguistic skills were well used on trips to Japan, Spain and Sweden, where weapons and ships were secretly purchased for the German Navy, largely ignoring the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. In Spain he was able to reactivate links with the Spanish Navy and within two days of his arrival in Madrid in June 1925 he had re-established contact with many of his old agents in most of the important ports. He had been instrumental in starting a secret U-boat construction programme with Japan in 1924 before it was discovered by the British and the programme was switched to Spain.26 With the help of his old friends Ullmann and Echevarrieta, he was able to set the financial wheels in motion. Both men were now able to realise their long-held dream of setting up a Spanish arms industry and helping Germany with her illegal submarine programme was a small price to pay.

Younger officers within the Spanish Navy were also keen to help. The U-boats of World War I had gained a legendary reputation and they were eager to obtain craft for their own navy. It soon became apparent that the only man they could do business with in Germany was Canaris, who understood the ‘Spanish Mind.’ In a few short months, Canaris had ‘… placed himself at the centre of the interlocking circles of German and Spanish naval rearmament. From now on nothing concerning relations with the Spanish Navy in Berlin took place without Canaris’s approval.’27

In January 1921 the German military intelligence service was reborn as the Abwehr, but at this time it was a tiny organisation with only a handful of officers and some clerical staff at HQ. By 1933 its chief was a naval officer, Captain Conrad Patzig, who had reluctantly taken the appointment which army officers looked down on as a dead-end job.28 As Patzig was in the navy, the Abwehr came under their remit, which was to prove good for both services.

It was Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, head of the Kriegsmarine, who wanted to keep the Abwehr in the navy’s control. He knew Patzig did not have the heart for the job, and so appointed the then Captain Wilhelm Franz Canaris to the post. Although Raeder was not overly fond of Canaris, he knew of his reputation and skill with intelligence work. Canaris accepted with enthusiasm, as at the time he was languishing in command of the coastal defences at Swinemunde. He sped across the country to Berlin to take up his new appointment on 1 January 1935. Patzig had hated the job, and whilst showing Canaris around the five-storey HQ of the Tirpitzufer, he asked him if he knew what he was getting into, especially with the Nazis. Canaris replied: ‘I’m an incurable optimist. And as far as those fellows are concerned I think I know how to get along with them.’29

OKW had taken the initiative over Spain and Gibraltar by sending Admiral Canaris on his fact-finding mission. On 23 July 1940 the group reached Madrid. There Canaris met with his Abwehr chief in Spain, Commander Wilhelm Leissner, code-named Gustav Lenz. Leissner had spent many years in South America at various jobs when he joined the Abwehr in 1937. Canaris immediately assigned him to Spain where he stayed until 1945.30

Leissner and the team visited the Spanish Minister for War, General Juan Vigon, and two of his staff, Colonels Martinez Campos and Don Ramón Pardo. They outlined their mission to plan a possible assault on Gibraltar with Spanish help. Vigon’s response was not encouraging, and to their surprise he revealed there was no Spanish plan to capture the Rock, and that there would be great problems in such an operation. Surprise would be almost impossible to achieve and difficulties with railways and roads would hinder the movement of large artillery pieces.31

Later Vigon took Canaris, Piekenbrock and Leissner to meet Franco. The Caudillo seemed more optimistic than his war minister. He thought the operation was possible, but was concerned over the fate of the Canary Islands if such action was taken, not to mention the economic issues of such a plan.32

The next day, Canaris and his team journeyed onto Algeciras with Colonel Pardo assigned to go with them. They used three houses in the town: Villa Leon, San Luis and Villa Isabel. The first of these had a view of Gibraltar Bay. These houses became popular and Ladislas Farago thought the number of visitors to Algeciras from the secret services had reached comical levels comparing them to: ‘… a veritable avalanche of reconnaissance ventures until Spain became the popular tourist attraction of the Abwehr.’ These missions overlapped one another, and reduced their assignments to ‘… a brief period of mainly hilarity in the Abwehr which was not otherwise noted for its sense of humour.’33

For two days they observed Gibraltar from various vantage points. Colonel Mikosch, in the disguise of a Spanish official, inspected the neutral zone and took a Spanish flight around the area. The formidable obstacles to an attack were noted as well as the irregular wind currents which ruled out the use of glider or parachute troops. On 27 July they discussed their findings and reached the conclusion that the Spanish would have to provide more information and better maps.

Most felt Vigon was right that surprise was not possible and transport through Spain would be difficult. Shortly after this they returned to Berlin, where Canaris, Piekenbrock and Mikosch prepared a plan of attack.

The assault force would need to be made up of two infantry regiments including mountain troops, two combat engineer battalions, an engineer construction battalion, and a company of mine experts. Up to twelve artillery regiments with heavy guns of 21cm (8 inch) and 88mm anti-aircraft guns were required, so 160 guns in all to give them a three to one advantage over the defenders. After a heavy bombardment by artillery and dive bombers, the infantry would go forward behind a drumfire laid by the artillery. They expected three days of heavy fighting to take the town and the Rock.34

As the proposals for this formal assault were filed, a different approach was considered. In late July another mission went to Algeciras led by Captain Hans-Jochen Rudloff who had been the leader of the Abwehr Company during the French campaign. His orders from Canaris were to explore the possibility of sending troops through Spain, without being detected, travelling in civilian clothes in closed trucks and making sure to avoid towns and cities. It was estimated that it would take three days to reach southern Spain, during which time other troops would move by sea and artillery would be dispatched to the port of Ceuta. But it soon began to unravel. Moving large bodies of troops through Spain without dectection was thought to be impossible. Anoter difficulty was that the cranes at Ceuta were not big enough to unload the heavy guns required. This plan was promptly shelved and Canaris did not present it as an option to his superiors. Neither operation had yet been assigned a code name.35

Hitler was not idle while these outings were gathering at Algeciras. Three days after seeing Raeder he told General Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen, commander of the VIII Air Corps and distant relative of the World War I flying ace, to meet him in Berlin. There he told Richthofen the struggle against Britain was to be intensified and one option was to attack Gibraltar. The Spanish were likely to demand to participate. If the British counter-attacked on the Iberian Peninsula Germany would move in. He asked him to go to Spain and see General Vigon whom he knew to be a good friend of Richthofen and, via that officer, send a message to Franco.

Richthofen met Vigon at Biarritz on 28 July to tell him about the Fuhrer’s idea. Vigon informed him of the Caudillo’s interest in the plan which others had voiced, but that he was uneasy about entering the war at this stage.

By now Sealion was coming under closer examination and disagreements between the army and navy had increased. On 31 July Hitler met with his advisors for a major study of the operation. It was agreed 15 September was the first possible assault date. If the arial attack were to lead to air superiority the landings would take place. If not they would be postponed until May 1941.36 Indeed the naval staff favoured an invasion the next spring. They argued that the navy was far too weak, not to mention that the weather in the channel was unpredictable and presented great hazards for the invasion fleets, none of which were purpose-built for the task.37

With the Army wanting to land at dawn, the periods of 20–26 August and 19–26 September would be suitable due to the favourable tides. The navy could not be ready by August and September was nearing the bad weather season. Even in the best of conditions the motley invasion fleet, made up of Rhine barges and Steamers, would cross the channel slower than Caesar’s legions 2,000 years before. They expected to lose 10% of their lift capacity due to accidents and breakdowns before the Royal Navy and RAF put in an appearance. Raeder used these arguments to insist on a narrow front invasion from Dover to Eastbourne, adding the Luftwaffe would be unable to protect the long front favoured by the Army from Dover to Portland. General Franz Halder, Chief of Army General Staff wrote in his diary that the army rejected the navy’s plea for a short front which revealed ‘irreconcilable differences’ between the two services and would be tantamount to putting the ‘troops through a sausage machine’. However Hitler would decide in favour of the Navy.38 Hitler’s proviso that failure to gain control of the air ‘under the circumstances was tantamount to postponement.’39

An odd omission by many at OKW was to question the lack of intelligence they had on Britain and the British. Keitel complained to Ciano about this in July: ‘The intelligence available on the military preparedness on the island and on the coastal defences is meagre and not very reliable.’40 The information coming from the Abwehr was erratic and they constantly over-estimated British strength citing the defending army between 23 August–17 September at about 35 divisions which was six divisions more than they actually had.41 In September the Abwehr tried to address these shortcomings by sending a large group of spies to the UK, but they were poorly trained and were captured quickly.

The one serious leak at the time which affected the British was through another channel, a cipher-clerk working at the United States Embassy in London, Tyler Kent. He got involved with Anna Wolkoff, the daughter of a White Russian Admiral, who held extreme anti-Semitic and pro-German views. She was a member of the ‘Right Club’ which was a right-wing fascist group.

Kent kept copies of the messages he had seen, and began showing them to members of the group, including highly secret correspondence between Churchill and Roosevelt. In one instance, a message referred to fifty old US destroyers which were given to Britain in exchange for the use of Caribbean bases. This would ‘have strengthened the hand of American isolationists whose influence Churchill was struggling to diminish.’42

The leaders of the ‘Right Club’ had a contact with the military attaché of the Italian Embassy. On 23 May details of the old destroyers’ arrangements were transmitted by the German Embassy in Rome to Berlin. However the club was under surveillance by MI5 and the Italian diplomatic telegrams decrypted by British codebreakers revealed almost all the US Embassy despatches to President Roosevelt were being passed to Rome. The US Embassy was alerted and all of the group’s members were arrested on 18 May. The group was led by Archibald Ramsay, a maverick Tory MP, and a former army officer in World War I with a good record. Kent was sentenced to seven years, Wolkoff to ten and Ramsay was interned until the end of the war.

It appears as if Canaris, although heavily engaged with Spain and able to visit Turkey at the time, paid little attention to Sealion, which was the bigger and more active operation. This is odd given the energetic part he played in Germany’s war effort between September 1939 and November 1940. Colonel Oscar Reile of the Abwehr was to become one of the services’s early historians and wrote of the hard-working Canaris of that time: ‘His membership in the resistance movement was one thing but premeditated treason was another. The fight against Hitler on the home front had nothing to do with the struggle against enemy secret services.’43 Canaris was trying to be all things to all men.

Canaris rendered excellent service during the Norway victory and as a result was promoted to the rank of full Admiral. Yet what he had seen in Poland had sickened him. When Hitler had first come to power Canaris had admired him saying ‘You can talk to the man’ and that he could be ‘reasonable’.44 However when the SS was formed in 1938 and the General Staff lost much of its power, which passed to the new High Command under Hitler, Canaris began to see the writing on the wall, and began to turn against him. The invasion of Poland confirmed his worst fears. He witnessed the horror of the SS burning the synagogue in Bedzin with 200 Jews inside.

He complained to Keitel about ‘extensive shootings’ and that the Polish ‘nobility and clergy were to be exterminated.’ Keitel replied to say that it was Hitler’s decision and warned him to go no further with his protests if he wanted to survive.45 There had been murmurings in the German General Staff about deposing Hitler, but their lack of action had led Canaris to despair of the generals and to accuse them of moral ‘cowardice’.46

From 1938 Canaris, a Catholic all his life, had established a close personal link to the Vatican. He had known Pius XII from his days as Nuncio Head of the Catholic diplomatic mission in Berlin, the equivalent of an embassy. His offices were used as a secret mediation, and as a link via the British Minister at the Holy See, Sir Francis d’Arcy Osborne. There was a risk in this to the Vatican and Catholics in Germany and Austria, should use of this avenue find its way to the Nazis. Dr Josef Muller was the main messenger Canaris used with the Vatican through the Pope’s German adviser Cardinal Ludwig Kaas, who was a Catholic priest as well as a professional politician.47 Various details were leaked through the Vatican to Britain about possible plots against Hitler and the Nazis, but they were not taken seriously.48 Muller was sent to Rome to warn the Allies about the attack in the west scheduled for 10 May 1940. Muller was almost rumbled on this occasion by the SD, but due to his quick thinking he deflected suspicion away from himself by having the date 1 May and point of entry Venice stamped in his passport after his mission by a friendly border guard, as the information about the leak reached Hitler on 1 May. The SD continued to eye the Vatican with suspicion but was no match for the Machiavellian labyrinth of that organisation.

When Churchill became prime minister, the British government began to take this strange link more seriously. Churchill would later write: ‘Our excellent intelligence confirmed that Operation Sealion had been definitely ordered by Hitler.’ He already had some idea of German Naval plans too.49 None of this information could have come to him via any ground reconnaissance, or through Ultra decrypts. Ultra was the signals intelligence obtained by breaking high level encrypted enemy radio traffic. It was not until May that Ultra began breaking significant codes, initially for the Luftwaffe. This ‘information’ must have come from a source within the German High Command. Only a few senior officers would be privy to such details, one of whom was Canaris. Historian Ian Colvin wrote: ‘The hand of Mr Churchill seems to have been guided at this time by somebody to whom the innermost counsels of Hitler were revealed.’50

One of Ian Fleming’s roles in the early months of the war was to act as liaison between the various intelligence organisations: SOE, MI6 and MI5, who poured oil on troubled waters whilst trying to avoid upsetting anyone.51

On 19 July SOE had come into being with Churchill’s directive to ‘set Europe ablaze’. Admiral Godfrey had set up NID 17 early in 1940 ‘to coordinate intelligence’ between NID and the others. SOE had been spawned by SIS and had a troubled relationship with its parent. This was not helped by the two directors who could not stand each other. Colonel Stewart Menzies ‘C’ hated the highland warrior Brigadier Colin Gubbins who was the head of SOE. It did not help either that the two organisations had conflicting remits. SIS largely dealt in covert operations whereas SOE were saboteurs out to make trouble. In such an environment, Fleming proved to be ideal at smoothing over hostility between the factions which would be particularly useful in Spain.52

Fleming made regular visits to Bletchley Park. They were having difficulty breaking the German Naval Enigma at Hut 8. Ian was sent by Godfrey to talk to Dillwyn Knox. ‘Dilly’, as he was known, was a brilliant classical scholar, papyrologist and cryptographer who in 1917 succeeded in breaking much of the German naval codes. It is unlikely Fleming was ever privy to the Ultra sources, but would have known about the code-breaking going on there. It was not until December 1941 that Dilly broke the Abwehr’s Enigma Key, before he died of stomach cancer in 1943.53

However the British had a stroke of luck when Arthur Owens was recruited by the Abwehr agent Nikolaus Ritter in 1938. Owens often passed himself off as a fanatical Welsh Nationalist. He had already briefly worked for SIS in 1936 when selling batteries for ships in Germany, by relating what he had seen in the shipyards of the Kriegsmarine in Kiel. In 1939 he was supplied with a miniature German wireless set he picked up at Victoria Station. He reported this to his handler Inspector Gagen of the special branch and the radio was examined by MI5. He was interred, rather to his surprise, in Wandsworth Prison under the Defence Regulation 18B but MI5 decided they could use him as a double agent and gave him the code name SNOW.54 Before his release they began transmitting with the radio from the prison, but John Burton, a prison warder and former Royal Signals soldier, took over his role with the radio. After his release, Owens travelled to Antwerp for the first of several meetings with the Abwehr. He returned from these meetings with codes and instructions which led to the breaking of the Abwehr’s hand ciphers. This in turn helped Bletchley reconstruct some of the Abwehr’s Enigma keys.55 The deception of the Abwehr, which began from a Wandsworth prison cell, would lead to the Double-Cross System which was to play a vital part in Operation Neptune, the D-Day landings in Normandy in 1944.56

Operation Felix plan 1940–41.

What the British did not know at this time was how far the Germans had gone in planning their attack against Gibraltar. It would not be until 9 November 1940 that it was assigned the code-name Felix by OKW.57

Two weeks later, Hitler signed the order for the invasion of Britain at the beginning of August 1940. General Jodl visited the OKW’s planning section, the National Defence Branch KTB at Bad Reichenhall, in the Bavarian Alps. He told its head, General Walter Warlimont, Hitler had made up his mind to invade Russia and thus Operation Barbarossa was born.

Barely a week before, thanks to the Fuhrer dithering so much, Warlimont and his staff were ordered to produce two further studies on Africa and Gibraltar. The planners had been unable to resolve the problems with Sealion. Now they were told to cancel their plans as the cross-channel assault on Britain had, at the very least, been postponed. What soon became apparent from the two projects of Egypt and Gibraltar was that the two forces could cooperate in attacking the British in the Mediterranean. However it was equally apparent the big stumbling block was Franco and whether Spain would agree to the move against Gibraltar. It would be a German operation, yet they could be seen to give the Spanish ‘control for propaganda purposes’.58

On 9 September von Richthofen was sent to San Sebastian, Franco’s summer headquarters, to try and find out when Spain would join the war. However the Caudillo was concerned about participating in a long war. He decided to send his brother-in-law Ramón Serrano Suñer, the Interior Minister, with a large entourage to Berlin on 16 September to see Hitler. Beigbeder, the Spanish Foreign Minister, did not go as he was seen as being too close to Sir Samuel Hoare and the British.

On the day they arrived, Serrano Suñer spoke with Joachim von Ribbentrop the German Foreign Minister, and the two men hedged around the main issue of Spain’s entry into the war. Suñer was shocked by Germany’s wish to have a Canary Island ceded to them as this had not been mentioned before. The next day he met Hitler for an hour and informed him that Spain would declare war once material difficulties had been resolved. Spain feared the Royal Navy, if they were to declare war, in regard to their Atlantic islands. Hitler closed the conversation with the view that he and Franco should meet, and this was a proposal which Serrano Suñer agreed with. Hitler followed this up with a letter to Franco.59

Franco’s reply to Hitler’s letter is dated 22 September. He thanked the Fuhrer for the ‘cordial reception’ of his minister. He noted the German wish to use Spanish bases, and said Germany would, as an ally, be free to use them as long as they would remain under Spanish control. He also rejected any German enclaves in Spanish Morocco for the same reason.

He feared a move against the Spanish Atlantic Islands by the British should Gibraltar be attacked. Spain was strengthening the defences there and they would welcome German aircraft in this respect. He finished with his most ‘sincere feelings of friendship and I greet you’.60

Serrano Suñer had a second meeting with Ribbentrop on 17 September which did not go well. Ribbentrop restated that Germany required one of the Canary Islands. Suñer would not hear of Spain ceding any territory. He suggested, instead, that maybe they should take one of the Maderia Islands from Portugal, a British ally.61 The only real agreement reached by Serrano Suñer’s mission to Berlin was that Hitler and Franco would meet and settle matters. Franco had suggested this should take place at the Spanish border.

A week later Hitler and Ribbentrop spoke with Count Ciano. They complained about Spanish demands for aid without any contribution to the German war effort. Ciano wrote in his diary that Hitler did not ‘speak about the current situation.’ Instead, he concentrated on the Spanish ‘intervention’ which he felt ‘would cost more than it was worth. He proposed a meeting with the Duce at the Brenner Pass and I immediately accepted.’ Ciano noted that there was no more talk of an invasion of England, and that the Fuhrer seemed worried at the prospect of a ‘long war.’ He also thought that Ribbentrop was ‘nervous’ and also noted that the Germans were ‘impeccably courteous toward us Italians’ while it was starkly apparent the Spanish mission ‘was not successful’.62

Serrano Suñer had gone onto Rome from Berlin where he complained bitterly to the Duce about German demands. Mussolini showed ‘little enthusiasm for Spain’s early entrance into the war.’ Their intervention could affect Italy’s role and prospects.63

Meanwhile the British, knowing full well that Spain was likely in the near future to join the Axis, were failing to make much headway in preparation for a potential invasion of Gibraltar other than through the efforts of NI. The SIS found Sir Samuel Hoare a ‘difficult colleague’.64 When, in September 1940, three men passing as Belgians were arrested on the border with France as British agents by the Spanish Security Police, they then confessed to working for the SIS. Hoare promptly ordered the passport control officer, who was the SIS representative, to go home. He also wanted the new SIS head of station, Leonard Hamilton Stokes, to go as well. It was clear that Hoare was in a funk as he often was when he saw ‘agent provocateurs’ everywhere ‘exciting anti-British demonstrations and harassing the lives of British subjects.’

David Eccles was in Madrid during August 1940 and he found the city to be ‘hot and tension is running high’. He put it down to: ‘the Germans have been stung to fury by their failure to get Spain into the war.’65

Leonard Hamilton Stokes had been setting up an early warning network against a possible German invasion in the border area with France. Much of this was now lost he complained to ‘C’ Menzies about ‘YP’ (code for Hoare) as becoming ‘extremely difficult’ and the ‘SIS had suffered’ as a result. Menzies understood that the Germans were trying to shut the SIS in Spain down and ‘“YP” had fallen for it’. In the end the passport control officer was sent home while Hamilton Stokes stayed despite being far from happy with having to work with Hillgarth who seemed to be able to manipulate Hoare.66

During August in London, Ian Fleming began work on the stay-behind operation for Spain and Gibraltar should the Germans move in. Where did the name Golden Eye come from? Ian would later name his Jamaican home Goldeneye after all. It seems likely that he was reading the Carson McCuller’s novel Reflections in a Golden Eye. Maybe the name, in some way, reminded him of Spain. The novel was not published until 1941 by Houghton & Mifflin, but was serialised in the October–November 1940 issue in the Harper’s Bazaar magazine.67