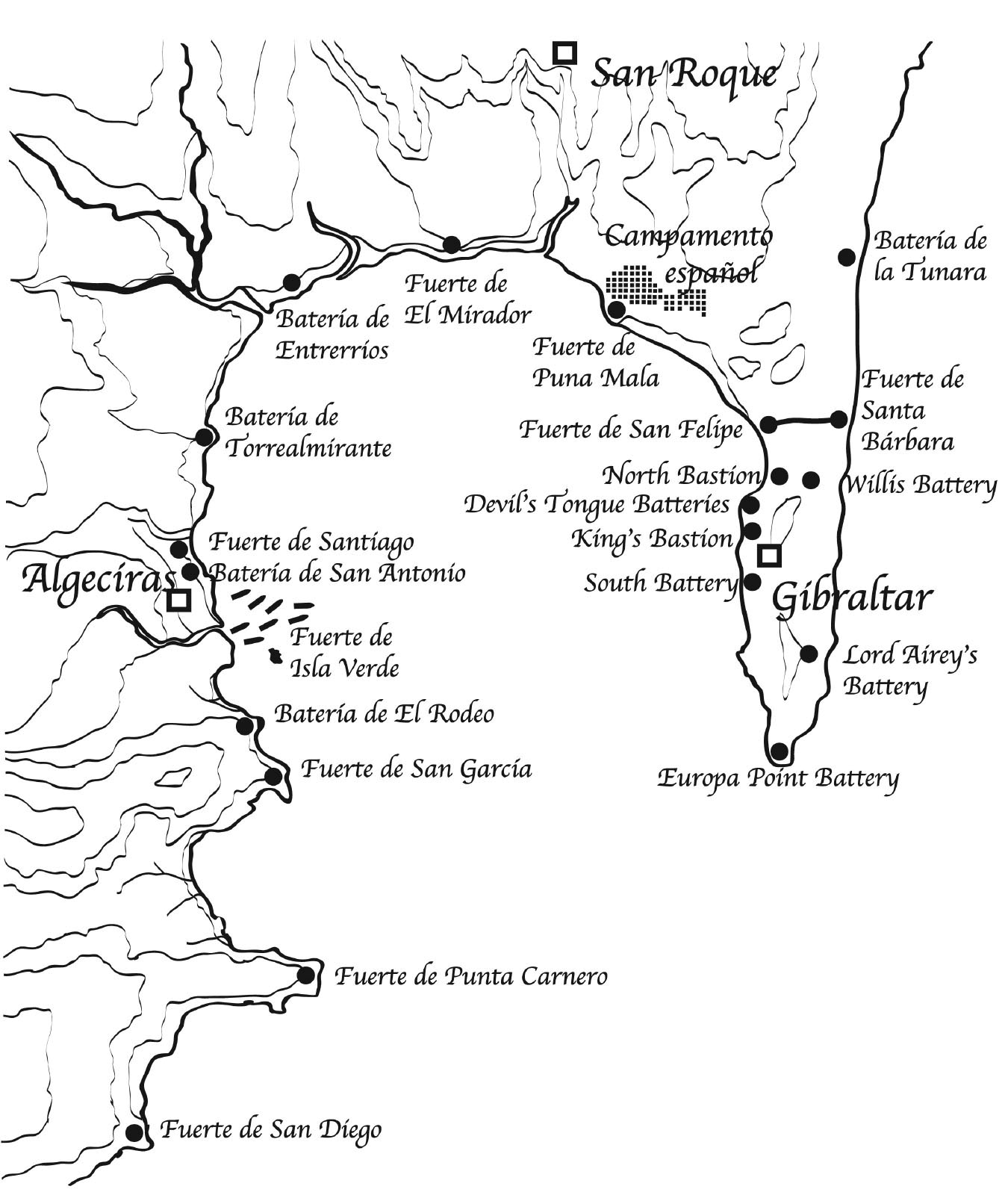

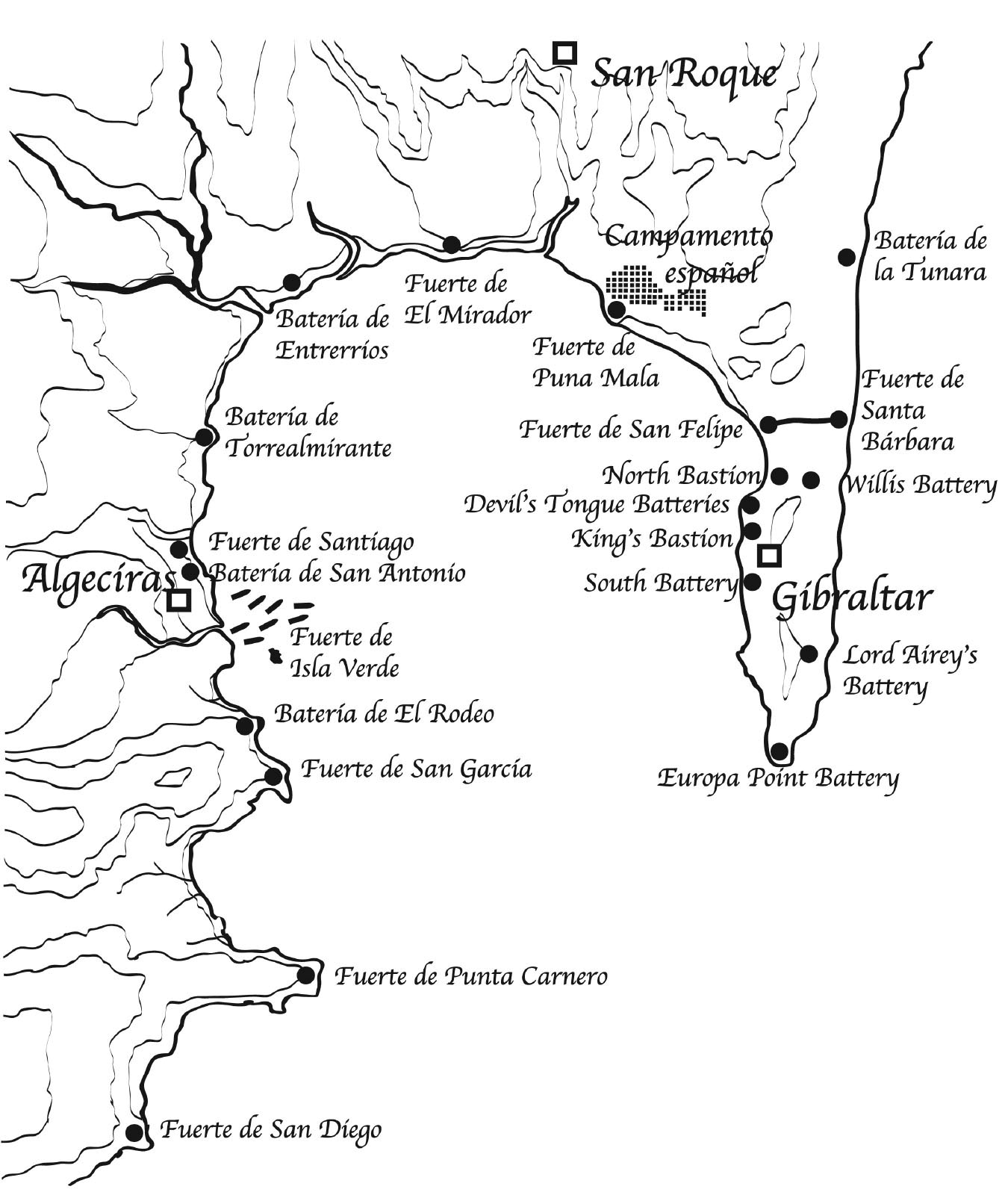

Bay of Gibraltar.

Brigadier Vivian Dykes wrote in his diary on Sunday 8 November 1942: ‘Heard on the radio that Algeria had asked for an armistice. We are in possession of Algiers and Oran. Some scrapping on the Casablanca front. Spain seems quiet. It looks a big success. Thank God!’1 He was then British secretary of the combined chiefs of staff committee in Washington, which was at the heart of policy making. He had spent the day with Bill Donovan, who had come up with the idea for the US to occupy North Africa. Both men likely had their minds on the time they had spent with Alan Hillgarth and Ian Fleming in Gibraltar and Spain and were wondering what the reaction there might be. Golden Eye was activated, and its agents were in position.2

A prolonged debate had taken place over several months during 1941-42 over the merits of a cross-channel invasion that year. Churchill favoured a Mediterranean strategy, because of his ‘soft underbelly’ of Europe theory. Operation Sledgehammer was put forward by the Americans, which would involve a landing to seize the French port of either Brest or Cherbourg during the autumn of 1942. They would then hold on to it while building up troops before a breakout the following year. The original Allied concept, Operation Roundup, was for a full-scale invasion of Europe in 1943. Sledgehammer was seen as far too risky to the British so the invasion of French North Africa, Operation Torch, was agreed as the Allied strategy in July 1942. Two subsequent events would reinforce that this decision was correct.3

The Dieppe Raid of August 1942, Operation Jubilee, where some 6,000 men were put ashore to gather intelligence, destroy port facilities and radar installations as well as boost morale back in Britain, was a disaster. Near 60 per cent of the landing force was killed or captured. The RAF lost double the amount of aircraft compared to the Luftwaffe, and the Navy lost thirty-three landing craft and a destroyer.

Ian Fleming, through the smoke and chaos from the pitching deck of HMS Fernie, watched the action as the destroyer steamed in circles near the town. Back in March he had come up with the idea, one of his better ones, to form a specialist Commando unit to capture intelligence material from enemy bases. He had learned how the Germans had done a similar thing during the battle for Crete. He put it to Godfrey in a memo with the heading ‘Most Secret’ before outlining his proposal. He argued that commandos should be sent with the forward troops during a raid, and if successful: ‘Their duty is to capture documents, ciphers, etc before they can be destroyed by the enemy.’4 Godfrey approved of the concept.

In July, the Intelligence Assault Unit was formed. It became 30 Assault Unit in 1943 made up largely of Royal Marine Commandos, along with naval men and some specialist army and RAF ranks from time-to-time. They were first bloodied at Dieppe. The unit became known as ‘Red Indians’ within NID, and later as ‘Fleming’s Red Indians’.5 During the raid they were tasked with entering the Kriegsmarine HQ, which was housed in a dockside hotel, to seize any secret documents and cipher machines there. Fleming’s men were on board the old China Station Yangtze River gunboat Locust for the voyage there. They were under the wing of 40 Royal Marine Commando, as 10 Platoon X Company, led by Lieutenant H. O. Huntington-Whiteley. They went over the side via scrambling nets into landing craft 2,000 yards from the main beach. Covered by a smoke screen before hitting the shore, they entered into a brutal maelstrom of noise and confusion.

From the Fernie with her 4-inch guns blazing away Fleming could see little of what was going on. The destroyer was hit near the funnel, killing one man and wounding several others. The raid began at 3am, and by 11am a withdrawal was ordered, and the destroyer was berthed at Newhaven sixteen hours later. In his report, Fleming wrote: ‘The machinery for producing further raids is there, tried and found good. Dieppe was an essential preliminary for operations ahead.’6 The raid confirmed that in order to land on a well-defended shore, a larger force with better coordination was required.

Out of the 370 men of 40 Commando that sailed to Dieppe, twenty-three had been killed and seventy-six wounded. Two of the dead marines, Samuel Bernard Northern, known as Ginger, and John Moir Alexander were from the Intelligence Assault Unit.7 The unit would land at night during Operation Torch on Sunday 8 November which would be a far more fruitful enterprise than Dieppe had been.

The second event to prove that Sledgehammer would be unlikely to work was the battle of Alam el Halfa on the Libyan-Egyptian border. During the first few days of September General Bernard Montgomery, the new 8th Army commander, won the defensive battle on Alam el Halfa ridge. The battle forced Erwin Rommel, the ‘Desert Fox’, to abandon his drive for the Suez Canal. With his supply lines precarious, he was forced to withdraw to his start lines. Montgomery waited to build up his strength for the second battle of El Alamein.

Bay of Gibraltar.

★

The Germans had managed to blow up a merchant ship and a small warship at Gibraltar with limpet mines. This was before Room 17M at NID, through Ultra, began reading their messages and the threat was defeated. British divers were sent down into the harbour area to watch the ships on the days of expected action. The Italians were to prove an altogether different proposition, and not just because the British could not read their radio messages.8

The Decima Flottiglia MAS, Tenth Light Flotilla of the Italian Navy, known for short as X MAS, was one of the best units of naval commandos to come out of World War II. During World War I, the Italian Navy had sunk an Austrian dreadnought battleship in the naval base at Pulo. Two frogmen had ridden a slow speed torpedo with a detachable warhead into the harbour, before placing it under the keel and sinking the 20,000-ton ship. In 1935 the Italians began to update the torpedo, resulting in the famous Maiale (pig) two-man human torpedo. During the course of the war, X MAS led by Commander J. Valerio Borghese, would sink over 200,000 tons of Allied shipping with pigs and limpet mines.

From October 1940 to August 1943, X MAS launched a series of attacks against Allied shipping in Gibraltar. The first attack was launched from the submarine Scire with the target being the battleship Barham. All three pigs broke down and two of the frogmen were captured, with the other four swimming to the Spanish Coast.9

They tried again in May 1941 using the Scire again. The submarine had been waiting at Cadiz for an opportunity. The pig crews had flown to Spain with forged passports on a civilian flight to help maintain their fitness rather than being cooped up on the submarine. However, once again, all the pigs broke down and the crews had to swim for the Spanish shore. The next mission in September was a success, sinking three British merchant ships, one of which was the Denbydale, a tanker inside the naval base. The pig in that case had avoided the small boat patrols and got through the nets to the target.10

In December X MAS achieved its most spectacular success in Alexandria by sinking the battleships Queen Elizabeth and Valiant in the harbour. Both ships settled on the bottom and were eventually refloated but the attack put them out of action for many months.

In 1942 X MAS sent a frogman team to Algeciras, where they hid in a villa. Using limpet mines on 14 July and 15 September they swam across to Gibraltar and sank five merchant ships. They used the Italian ship Olterra as a base. This ship was damaged and lying on the bottom near the breakwater at Algeciras, with parts of the superstructure visible above the surface.

Later an underwater exit was constructed to use pigs brought in by submarines. It was kept secret from the Spanish and although there were many British agents in the town, none knew anything about it. X MAS, operating from the Olterra, sank fourteen Allied ships totalling 75,578 tons.11

Although the captured Italian nuotatori (frogmen) had revealed nothing under interrogation, British intelligence in Gibraltar suspected that there was a ship or land base on the Spanish side of the bay, from where the raids were being staged. Alan Hillgarth was sent to investigate and suspicion fell on the Olterra. He protested to the Spanish authorities, which led to the Spanish Navy searching the ship but finding nothing. After Italy collapsed in 1943, Hillgarth found out from a contact in the Italian Embassy that there had indeed been a special compartment on the Olterra from which the frogmen operated. The ship had been interned originally with her crew, but over the months her crew had been slowly swapped with members of X MAS. The ship was finally towed to Cadiz where she was taken apart and the compartment found below the waterline.12

A keen swimmer and diver, Ian Fleming was intrigued by the exploits of X MAS, and has Bond refer to them in Thunderball, when he tells Felix Leiter of the CIA that the Olterra affair was ‘one of the blackest marks against Intelligence during the whole war’.13 Emilio Largo, an Italian and Bond’s enemy in the book, is a lieutenant of Ernst Stavro Blofeld the ‘founder and chairman’ of SPECTRE, ‘The Special Executive for Counter-Intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge and Extortion’. Their plan is to hijack a Vindicator Bomber carrying two nuclear bombs, so they can hold the world to ransom. Largo uses his luxury motor yacht, the Disco Volante, to recover and move the bombs, which has its own below the waterline compartment.14

In Live and Let Die, Fleming has Bond destroy Mr Big’s motor yacht Secatur with a limpet mine he attaches when the boat is anchored off Jamaica. The mine explodes at just the right time as Bond and Solitaire are being towed at speed toward a reef by the Secatur where they will be torn to shreds by the razor-sharp coral.15

William Stephenson claims that Fleming did an agent’s sabotage course in Canada and was taught about limpet mines which gave him the background for this scene, but there is some dispute whether Ian Fleming ever attended a course for OSS and SOE agents at Oshawa on the shores of Lake Ontario. According to Stephenson he is supposed to have emerged from the course with top marks. The course would have included him completing a long underwater swim, at night, and placing a limpet mine on an old tanker without being detected. However there is no evidence he was ever there on a course, though it is possible that he visited the establishment during a conference he attended at Quebec in 1943.16 John Pearson, the Fleming biographer, argued that the school at Oshawa ‘provided him [Fleming] with a lot of the tricks he would pass on to James Bond’ and in the long run it helped him decide ‘just what kind of an agent Bond must be’. Stephenson told Pearson that Fleming ‘was an outstanding trainee’ but that he lacked the temperament to make a good agent. He did not lack for ‘courage’ but had ‘far too much imagination’.17

In September 1942, Fleming and Godfrey were due to go to Washington when they received in the news that Godfrey was to be promoted to Vice Admiral. They were told this on the same day that Pound told him his appointment as DNI was over. Godfrey could be bad-tempered and impatient, which had made him enemies within the Joint Intelligence Committee. He also had a difficult relationship with Churchill, who he felt interfered too much in things he had little knowledge of. He left in December 1942 having held the post for three and a half years. At that time, only Blinker Hall had held the role for longer.

It remains ambiguous as to why Godfrey was sacked in September. Pound sent him a note the next day which said that the JIC could no longer function ‘as long as you were a member’.18 It seems that the trigger was Godfrey sending Admiral Andrew Cunningham intelligence summaries, which contained information on all three services. This had been approved when Cunningham was commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean, but not when he went to Washington. The summaries continued whereas Field Marshal Dill, on the same mission, was only getting assessments rather than full intelligence. It never occurred to Godfrey that this would upset the other services. It is possible that Dill complained, but the significant factor was that the Vice Chief of the Naval Staff VCNS Admiral Henry Moore and Pound would not support Godfrey. Pound might well have had more pressing matters on his mind. He was extremely ill and in a little over a year would be dead. He suffered from a brain tumour, which seriously affected his concentration. He died on 21 October 1943, Trafalgar day.19

The trip to the USA still went ahead but it had lost some of its sparkle. In New York they visited the NID office before moving onto Washington, where closer relations with the US Navy were being formed. German U-boats had enjoyed dominance off the eastern seaboard of the United States and in the Caribbean. In the early months of 1942, they sank twenty-five ships in ten days. In February of that year, the Kriegsmarine had introduced a new four-rotor Enigma machine. This meant that it took longer for Bletchley Park to break the messages, and so the Allies were unable to stop many of the attacks in early 1942 during the Battle of the Atlantic. Godfrey had sent some of his best people to America to improve intelligence and direction-finding, which is the art of listening to high frequency radio messages to obtain a fix on a submarine’s position. Captain Rodger Winn, an expert on submarine tracking, managed to convince Admiral Ernest King USN to adopt the tactic. This was not an easy task given that the US Fleet commander could be notoriously difficult to please.20 Godfrey was thrilled when direction-finding was adopted, and it was possibly his greatest contribution to the war.

Later Godfrey went to Canada while Fleming went to Jamaica for an Anglo-American conference to discuss further naval cooperation in the Caribbean where over 300 ships had been sunk. The SIS agent Ivar Bryce, a life-long friend since he had met Ian and his brothers on a Cornish beach when they were boys, went with him. Bryce had been working for Stephenson in Washington and North America in the ‘dirty tricks’ department, encouraging anti-German feeling wherever he could. They took the Silver Meteor train to Miami, which had started running in 1939 from New York. The train is The Silver Phantom in Live and Let Die, which runs from New York, Washington, Richmond, Savannah, Jacksonville and Tampa. On board compartment H, in car 245, a space is reserved for Bond under the cover name Bryce.21

In Jamaica they stayed at Bellevue, a 200-year-old plantation house where Nelson once stayed, owned by Bryce’s wife. It is close to Kingston where the conference took place at the Myrtle Bank Hotel. Bryce hoped that Ian would come and stay when the war was over, but the island had not been at its best, and the weather had been ‘really dreadful’. Yet Ian had loved the island, and told Bryce on the plane leaving Jamaica that one day ‘I am going to live on Jamaica’ and ‘swim in the sea and write books’.22

By the end of September, Ian had arrived back in London to concentrate on Operation Torch. He had to make sure Golden Eye was in place and ready and that his ‘Red Indians’ of the Intelligence Assault Unit would soon be storming ashore in Africa. Godfrey was still on hand, but had received a new job offer as flag officer commanding the Royal Indian Navy in Bombay, leaving his desk at NI in November. He thought about it for a day and sought advice from his old friend Cunningham and came to the conclusion ‘that in war time you must do what you are told’. He had also wanted to see the East and the Pacific and so ‘India appealed to me strongly’.23 He would be replaced as DNI in the New Year by Captain Edmund Rushbrooke, who was not keen on the job. Joan Saunders, who worked at NID, felt that Godfrey was ‘too good’ for the job while ‘Old Rushbrooke was no good, and if it hadn’t been for Ian Fleming the whole thing would have run down.’24

In Spain, Alan Hillgarth was ready and waiting to supervise and direct the agents of H section of the SOE. Alan had a portable wireless transmitter and two cars in case his staff had to take to the road. One was a Humber Super Snipe ‘with huge tyres’. He loathed that car, after the steering broke on it one day at 40mph and nearly killed him.25 It had cost £196.18.2d to restore it.26

He had recommended for a lorry to be ready at Madrid to carry the transmitter along with a petty officer telegraphist. In a report from Birley to Hillgarth, he outlined the staff needed on the ‘outbreak of hostilities’ as two officers, two telegraphists, and three Royal Marines to join him by road. He noted that: ‘Petty Officer Telegraphist Bowling is a wizard and all his W/T routines are accurately taped with Admiralty, Gibraltar, and the Army set at Spanish Military G.H.Q. (if required).’27 Hillgarth wrote in his Golden Eye report in November 1941 that he wanted three officers in Gibraltar to be ‘under my orders. I reckon that with this personnel and this means of communication and transport, I shall be in a position to maintain efficient liaison between the Spanish minister of Marine, wherever he may be, and Gibraltar.’ It is clear that he thought they would be dealing with the Spanish against the Germans.28

Ambassador Hoare was in Madrid on the day of the Torch landings and spent the afternoon ‘shooting wood pigeons’ to give the impression of unconcern amid all the rumours swirling around:

I had several hours to think of the convoys that were already on their way and the Spanish reaction that the operation would excite. When I finally received the telegram that the expedition had begun to land, I was for the same reason careful not to ask for a melodramatic interview in the middle of the night. I accordingly arranged to see Jordana at 11am on Sunday Morning.29

The US Ambassador to Madrid, Carlton Hayes, telephoned Foreign Minister Jordana at one o’clock in the morning of Sunday 8 November to tell him about Operation Torch. As the invasion was mainly made up of American forces and under American command, Hoare was happy for Hayes to take the lead. If anything Jordana was relieved, as he had become aware in the weeks before that the Allies would open up a new front which could involve Spain.30

Franco met with his ministers the next day, where they considered calling up the army reserves. General Asensio and other ministers argued for a pro-German stance, but Jordana wanted strict neutrality. That same day Franco received a cordial letter from President Roosevelt in which he stated that these moves are in no shape, manner or form directed against the government or people of Spain.’31

With the agreement of his ministers Franco decided to wait before calling up any troops, for fear that the Allies would interpret this as an act of aggression. Three days later, rumours of a German move through Spain were rife and that Hitler would seek passage for his troops. The government agreed they must refuse any request and that they would begin a partial mobilisation to increase Spain’s Army to 700,000 men to cover the passes in the Pyrenees. Jordana continued to try and gauge German intentions.32

On 23 October Montgomery’s artillery had opened fire and begun the final battle of El Alamein. By 6 November the Africa Korps was in full retreat. Rommel had lost half his army and nearly all his tanks and could not recover the losses. On 19 November the Red Army launched its powerful counter-attack at Stalingrad. Hitler’s response was to occupy the whole of France and to seize control of Tunisia to pour troops in to gain a final foothold in North Africa at the expense of the Eastern Front. The German troop movement near the Pyrenees caused concern in Madrid and Lisbon. Salazar sent a press release to say that the German ambassador to Madrid had assured Spanish neutrality, which forced the German government to make a similar statement.33

The Abwehr and Admiral Canaris got much of the blame for the intelligence failure in not predicting the Allied invasion of North Africa. Jodl commented: ‘Once again, Canaris has let us down through his irrationality and instability.’ Hitler said to Keitel that ‘Canaris is a fool’ and that the ‘Abwehr reports were always defeatist and always wrong.’34

Yet there had been warnings. The British had not woven together an elaborate deception plan for Torch, but they had produced a lot of ‘noise’ about various possibilities including, Norway, Dakar and Sicily as well as a large relief effort for Malta.

Some fairly accurate Abwehr reports came in, including one from the Vatican in October which indicated that while the Americans would land in Dakar, the British would land in Algiers. Captain Herbert Wichmann of the Abwehr sent a detailed report which indicated that an Allied landing in French North Africa was possible. Canaris had also been supplied by the pro-German Muslim leader Hadji Amin Mohammed al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, who the Admiral had known since 1938, with a detailed report on an Allied landing in North Africa for early November between the 5th and 10th of the month. Nine American Divisions would be shipped direct from the USA and a further five from Britain. This report appears to have come direct from Muhammad V, the Sultan of Morocco, who changed sides in the war frequently, depending on which side seemed to have the upper hand. Canaris took it to Keitel who dismissed it, insisting that the Allies did not have enough ships or landing craft for such an undertaking. Canaris did not press the point. Colonel Friedrich Heinz, who served under Canaris, said after the war that the Admiral had been intentionally vague with the facts about the North African landings.35

A trait existed in the German high command, emanating from Hitler and infecting OKW, that intelligence which contradicted his own view was not to be investigated. It did not matter where that intelligence came from, for he had the same approach with the ‘Cicero’ documents from Ankara that were supplied by an agent of the SD. These documents revealed that Germany was facing an overwhelming coalition that would not fall apart, yet he chose not to listen.36

The Torch landings marked the start of a string of events that would lead to the demise of the Abwehr and Canaris. Torch was followed by the invasion of Sicily and the fall of Mussolini, both of which the Abwehr failed to predict. In January the Abwehr agent Erich Vermehren and his wife in Istanbul chose to defect to the British. The Vermehrens were not a particularly great coup for the British, but their propaganda machine went into overdrive to overplay their importance. However, their defection had an effect which went beyond intelligence. It caused consternation in Germany and marked the virtual demise of the Abwehr as an effective service, before being taken over by the SD. Hitler was furious and summoned Canaris to a meeting which would prove to be the Admiral’s last with the Fuhrer. The defection seemed to indicate that ‘the crew was abandoning ship’ and Hitler told Canaris that his service was falling apart. The Admiral responded that it was ‘hardly surprising given that Germany was losing the war.’ As a result, Hitler decided to put the Abwehr under the control of Himmler and Ernst Kaltenbrunner, head of the SD and RSHA.37

★

The two World War I vintage destroyers HMS Broke and HMS Malcolm brought Ian Fleming’s commandos, along with American Rangers, towards the port city of Algiers on the moonless night of 8 November. Commander Henry Fancourt commanded the two ships of Operation Terminal, and their mission was to seize the harbour and prevent damage to its facilities. The commandos for this operation were known as the ‘Special Engineering Unit’ and came under Mountbatten’s Combined Operations. Despite this, Fleming still kept a good eye on his protégés and their development. They were now commanded by Commander Robert (Red) Ryder VC, one of the heroes of the St. Nazaire raid. He built his unit around three sections from the Royal Marines Commandos who came from both the army and navy. The navy troop initially only had five naval officers in it who had a ‘technical’ role. Their job was to instruct the men from the other troops in which loot to grab. The two other troops also had a fighting role with two officers and twenty men each.

The bow of the Malcolm was reinforced with concrete to crash through the Algiers harbour boom. The American troops were to take and hold the port area, while other troops landing on beaches to either side of the town would soon relieve them. The commandos’ job was to get into the French Admiralty building on the Mole and grab intelligence material.

Due to the dark night, Malcolm and Broke could not find the narrow entrance into the harbour. Both ships ran in close to the harbour wall on repeated sweeps. As Malcolm was about to finish an abortive run, she was lit up by searchlights and came under heavy fire from French shore batteries. The ship was hit several times, with three out of four boilers put out of action, and ten men were killed and twenty-five wounded. The ship lost speed and listed to starboard whilst heading back out to sea. Broke was instructed to lay a smoke-screen to cover the Malcolm. On her fourth attempt, Broke sliced through the boom and came alongside the mole. By then it was 5.30am and getting light, when the American troops landed and took the commercial port area. At roughly 8.00am, the Vichy French started firing again. The Broke was hit and was forced to leave at 10.30am. The ship was hit again when sailing out to sea, and had to be taken in tow by the Hunt class destroyer Zetland before sinking two days later.

The American troops were now holding the harbour under Lieutenant-Colonel Edwin T. Swenson. They were heavily outnumbered and, when faced with tanks, they surrendered.

The 30AU Commandos managed to transfer from the crippled Malcolm to HMS Bulolo, the HQ ship, from which they got ashore twelve miles west of Algiers. From there they set off towards the city and the secondary target of the Italian Armistice Commission HQ. Lieutenant Dunstan Curtis RNVR, commanding the naval troops, praised Fleming’s detailed briefings and: ‘how much thought he had given to our whole show. He had organised air pictures, models, and given an expert account of what we were to look for when we got to the enemy HQ.’38

The next day the commandos took the Italian HQ, capturing seven Italians. Admiral Darlan surrendered Algiers to the Americans, but the wily sailor said that he lacked the authority to do the same with the rest of the country. In the German Armistice Commission, from where the Abwehr ran a cell, Curtis found an Enigma machine. It was ‘a “KK” rewired multi-turnover Abwehr machine’ along with six weeks worth of traffic. The machine was flown back to England via Gibraltar and two tons of documents followed by sea. The ‘back traffic was soon broken’, and from it a detailed picture emerged of Spanish collaboration with the Abwehr.39

Many regard From Russia with Love as the best Bond novel. In it, SMERSH (Death to Spies), the Soviet counter-intelligence department, attempt to take revenge on the British Secret Service by luring James Bond to Istanbul to meet the beautiful Tatiana Romanova, who apparently wants to defect. She would bring with her a ‘Specktor’ machine that could decipher Soviet radio traffic. Bond thinks this would be a ‘priceless victory’ and for the Russians, ‘a major disaster’.40 The ‘Specktor’ described is similar to an Engima machine. It is ‘case size’ and has ‘three rows of squat keys rather like a typewriter’.41 What happened next in Algiers unfolded like the plot of a spy novel. Two days after Darlan surrendered Algiers, he called for a ceasefire in the rest of the country despite saying that he did not have the authority only two days before. The US Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower gave him the authority by confirming him as the political head of French North Africa. This was a move which infuriated the Free French under General de Gaulle, as well as Churchill who saw Darlan as a ‘dangerous, bitter, ambitious man’.42

The SIS had smuggled General Henri Giraud out of France by submarine to take over in French North Africa. He had been taken prisoner at the fall of France, but had escaped from Konigstein Castle, which his German prison guards regarded as escape-proof. The castle was situated near Dresden on the left bank of the River Elbe, and he escaped with a rope which was smuggled to him in cans of ham. It was quite the achievement for a man of sixty. He got back to France in the spring of 1942.

An American officer watched Giraud approach the submarine Seraph in a fishing boat from the conning tower. He wrote: ‘His gloved hands were folded over a walking stick and a raincoat was thrown over his shoulders like a cloak. It was the first time I had ever seen him and he looked rather like an old-time monarch visiting his fleet.’43

He arrived in Algiers on 9 November to take over. The scheme was codenamed Orange. Three days later, Sir Stewart Menzies ‘C’ head of the SIS was asking about Giraud’s relationship with Eisenhower.44

Churchill, meanwhile, warned Roosevelt that ‘deep currents of feeling are stirred by the arrangements with Darlan’ and that he had ‘an odious record’. Menzies had told Sir Alexander Cadogan, permanent head of the Foreign Office, that Churchill’s call for the French Resistance to set ‘Europe Ablaze’ had little hope of success if they dealt with fascists like Darlan. On 22 November Darlan announced that he was taking control of the French Empire. The British cabinet then met in a secret session. Three days later, Darlan’s assurance that he would bring the French Fleet over to the Allies proved false, as French officers in Toulon scuttled seventy-three ships as the Germans were arriving. Cadogan began to wonder if they should eliminate Darlan. He wrote in his diary that the Americans had let ‘us in for a pot of trouble’ and that ‘We shall do no good until we’ve killed Darlan.’45

Fernand Bonnier de la Chapelle was born in Algiers and was an ardent monarchist who detested the Vichy regime. He was a youthful 20-year-old with the hint of humour in his face. He was taking training at a joint OSS/SOE base at Ain Taya, near Algiers, waiting to be parachuted into France. Fernand was with a group of resistance members that had seized control of Vichy buildings on 8 November. On Christmas Eve, after he and two friends drew lots, he was chosen to shoot Darlan. He entered the Palace of State and waited for Darlan. As the Admiral returned from lunch, he shot him twice. One bullet entered his head and the other his chest. It is said that Darlan’s last words were: ‘The British have finally done for me.’46

Fernand was arrested and questioned. He admitted that he belonged to the Corps Francs d’Afrique, a resistance force formed by Giraud. Rumours swirled around Algiers that it had been a plot orchestrated by the SIS. Fernand was convicted, condemned and executed. Right up until the end, he did not believe the firing squad would shoot him, and assured the priest that they would be using ‘blank cartridges’.47 The court martial was organised by Giraud and conducted in secret with no Allied officers present.

Within hours, Giraud was appointed high commissioner of French North Africa as Menzies had intended. Menzies happened to be in Algiers at the time. On the day Darlan was shot, he was having lunch with Squadron Leader Frederick Winterbotham, who was in North Africa on Ultra business. The news came in that Darlan had been shot dead only a few hundred yards away. Winterbotham thought that the murder came as no surprise and it was as if ‘they could not have cared less’.48

The pistol said to have been used to kill Darlan was a .22 semi-automatic Colt Woodsman issued to the assassin from the SOE stores. The officers in SOE all denied having any role in the assassination.

Weeks after the Torch landings, Operation Golden Eye was stood down, along with the contingency plans, Operations Backbone and Backbone II. Backbone had been set up to counter any move by the Germans into Spain. The plan was to seize control of Spanish Morocco where there were 100,000 ‘poorly equipped’ Spanish troops, and the area around Gibraltar.49

On 22 December Hitler invited Admiral Raeder to dinner. Most of the time was spent discussing the Iberian question. Raeder made a strong case for an Allied invasion of Spain as a ‘strategic necessity’. This impressed Hitler who ordered Gisela to be reactivated. Admiral Canaris was sent to Spain on 26 December to try and find out if the Spanish would resist an Allied landing. As a result, even with the deteriorating situation at Stalingrad, Hitler cancelled all troop transfers between the eastern and western fronts, and ordered three mobile units, including one armoured division, transferred to the west.50

The Allied concerns were similar, and within the first few weeks of 1943, Backbone II was drawn up to deal with (a) Spain starting hostilities or (b) a German invasion of Spain. The plan would include a three-pronged invasion of Spanish Morocco and also to establish a bridgehead into southern Spain around Gibraltar. An invasion force would arrive directly from the UK. However, like many other contingency plans of both the Allies and Axis, they were never used.51