12 ORIGINAL ART: OWNERSHIP, INSURANCE, SUBMISSIONS, AND RESALE PROCEEDS

Of course the artist owns whatever original art he or she creates, subject to the “work-for-hire” exception discussed on pages 37–44. This art owned by the artist must be protected against unintentional transfers when reproduction rights are sold as well as against loss, damage, or theft. When submitted either for the purpose of selling the original art or reproduction rights in that art, the submission form must provide for the safe return of the art.

As discussed in chapter 7, moral rights connect the artist to original art after sale. In a similar way, France and other countries give the artist a right to share in the proceeds from certain sales of art. California has used this concept as the basis to enact an art resale proceeds law that gives artists a right to share in profitable resales of the art.

Issues pertaining to original art are discussed throughout this book. However, this chapter focuses on certain unique or novel issues of significance to the artist.

Ownership When Selling Rights

California, Georgia, Nevada, New York, and Oregon have enacted statutes to protect the artist’s ownership of original art when reproduction rights are sold. This addresses the problem of a client who buys reproduction rights but also believes the original art is being sold without an additional fee. The state laws will force the parties to discuss this issue and reach agreement about it. This is especially important in view of the fact that the client making reproductions is in possession of the art. In states without such laws, the artist might be found to have sold the art by an oral or implied contract.

The California and Oregon laws resolve any ambiguity as to what reproduction rights are transferred in favor of the artist. I originally drafted this bill for presentation to the National Conference of State Legislatures. The support of the Graphic Artists Guild and the American Society of Media Photographers was crucial to the enactment of these laws. The California law reads as follows:

988. Ownership of physical work of art; reservation upon conveyance of other ownership rights; resolution of ambiguity (a) For the purpose of this section: (1) The term “artist” means the creator of a work of art. (2) The term “work of art” means any work of visual or graphic art of any media including, but not limited to, a painting, print, drawing, sculpture, craft, photograph, or film. (b) (b) Whenever an exclusive or nonexclusive conveyance of any right to reproduce, prepare derivative works based on, distribute copies of, publicly perform, or publicly display a work of art is made by or on behalf of the artist who created it or the owner at the time of the conveyance, ownership of the physical work of art shall remain with and be reserved to the artist or owner, as the case may be, unless such right of ownership is expressly transferred by an instrument, note, memorandum, or other writing, signed by the artist, the owner, or their duly authorized agent. (c) Whenever an exclusive or nonexclusive conveyance of any right to reproduce, prepare derivative works based on, distribute copies of, publicly perform, or publicly display a work of art is made by or on behalf of the artist who created it or the owner at the time of the conveyance, any ambiguity with respect to the nature or extent of the rights conveyed shall be resolved in favor of the reservation of rights by the artist or owner, unless in any given case the federal copyright law provides to the contrary. (Civil Code, section 988)

This law bolsters the protection for the artist provided by the copyright law and offers a model that can be enacted in other states.

Ownership of Negatives

Photographers will want to know about an unusual feature of the law relating to physical negatives. If the photographer works independently, of course, all rights in the copyright and all negatives will belong to the photographer, unless a contract transfers rights. If the photographer works for hire, the person hiring the photographer will own the copyright. This means that the photographer cannot sell or distribute any copies of those photographs without the permission of the copyright owner. But the photographer may be deemed to own the negatives, unless the photographer agrees otherwise. The increasing dominance of digital photography does nothing to diminish the importance of owning “negatives.” For example, many digital photographers shoot and store images in an uncompressed “RAW” file format that retains the maximum amount of information a digital camera’s sensor can capture. While subsequent publications of the image generally require some additional processing of a “digital negative,” the original RAW files are generally retained by the photographer. The photographer becomes, in essence, a warehouse, storing negatives or RAW files to meet requests for photographs from former clients (Corliss v. E. W. Walker, 64 F. 280). The question of whether RAW could be treated the same as negatives is not one that courts have yet addressed. However, there is widespread consensus within the digital photography community that RAW is the digital equivalent of a physical negative. To that end, many influential photographers have thrown their support behind an “open RAW” initiative that would encourage standardization of RAW file formats, and prevent camera manufacturers from imposing proprietary standards on what photographers believe to be the “direct equal to film negatives.”

The rule may have ramifications for fine artists who employ photographers to make a photographic record of work. For example, the photographer Paul Juley was hired by portrait artist Everett Raymond Kinstler to photograph Kinstler’s paintings. After Juley’s death, an issue arose as to the ownership of the negatives that Juley had retained. Kinstler said Juley had orally agreed that the negatives belonged to Kinstler and Juley kept the negatives only for convenience. Juley, however, had bequeathed the negatives with the rest of his work to the Smithsonian Institution. Kinstler, presumably barred by rules of evidence from giving self-serving testimony regarding a contract with a man no longer living, found that the general rule applied giving ownership of the negatives to the photographer. So the negatives today belong to the Smithsonian Institution. The moral is, once again, to use written agreements.

Insurance and Risks of Loss

The artist may wish to insure original art in order to receive insurance proceeds in the event of its loss or destruction. The artist should seek an agent who is familiar with insuring art works. Such insurance may cover art only when in the artist’s studio or may extend to cover art that is in transit. Valuation can be difficult with art, and the artist might even have to incur the extra expenses of an appraisal. The fact that an insurance company has the artist pay premiums based on a certain valuation of the art does not necessarily mean the company will not dispute that valuation in the event of a claim. Inquiry should be made of the agent regarding this issue.

The artist should ascertain whether certain risks are excluded from coverage, such as losses caused by war, faulty film processing, or mysterious disappearances. Also, once the artist has insurance, exact records as to the art subject to the insurance become crucial in order to document claims. If the artist’s premises or work may be dangerous, the artist should consider liability coverage to pay for possible accidents.

If the artist has no insurance and the work is damaged or stolen while in the artist’s studio, the artist simply loses the work. But if the artist has sold the work, when does the risk of loss pass to the purchaser? The general rule is that if a work must be shipped, the risk of loss passes to a purchaser upon delivery. Thus, the artist would normally bear the risk of loss while the work was being shipped to a purchaser.

However, if the purchaser buys the work at the artist’s studio and leaves the work to be picked up later, the purchaser bears the risk of loss. This is because a sale by a non-merchant seller under the Uniform Commercial Code passes the risk of loss to the purchaser after such notification as would allow the purchaser a reasonable opportunity to pick up the work. For example, when a bronze sculpture was sold along with the contents of a house, it was not reasonable to expect the purchaser to take possession of the sculpture within twenty-four hours of being given the keys. The risk of loss remained on the seller, but might have shifted to the purchaser if the purchaser had a longer period in which to pick up the sculpture (Deitch v. Shamash, 56 Misc.2d 875, 290 N.Y.S.2d 137). The contract of sale offers the artist an opportunity either to shift any risk of loss to the purchaser or to provide for insurance on the works sold.

Bailment

A bailment is a situation in which one person allows his or her lawfully owned property to be held by another person. For example, an artist might lend a work to a museum, leave a painting for framing, drop off a portfolio at an advertising agency, or leave film to be developed at a film lab. In all of these relationships, when both parties benefit from the bailment, the bailee (the person who takes the artist’s property) must exercise reasonable care in safeguarding the work. If that person is negligent and the work is damaged or lost, the artist (as the bailor) will recover damages. Even if the work has no easily ascertainable market value, damages would still be awarded based on the intrinsic value of the work to the artist.

However, the reasonable standard of care required in a bailment can be changed by contract. Often, for example, film labs will require an artist to sign a receipt, which limits the liability of the lab to the cost of replacing film that is ruined. This is so, despite the great value that may exist in the images recorded on the film. Similarly, a museum, a frame maker, an advertising agency, and so on might seek to limit liability, perhaps to the extent of requiring the artist to sign a contract under which the artist would assume all risks of injury to the work.

The artist should seek just the opposite—that is, to have the other party agree to act as an insurer of the work. This would mean that the other party would be liable if the work were damaged for any reason, even though reasonable care might have been exercised in safeguarding the work. Even if the artist signs a limitation on the liability of a lab or other bailee, the artist should document how any loss occurs. If the bailee is extraordinarily negligent, it may be that the limitation will be invalid. At least, the language of the limitation should be closely examined before the artist decides whether or not to make a claim.

A technical issue that arises is whether all of the artist’s bailments are for mutual benefit or whether certain bailments would either be for the sole benefit of the bailor or the sole benefit of the bailee. If the bailment is for the sole benefit of the bailor, the bailee will be liable only for gross negligence. If the bailment is for the sole benefit of the bailee, the bailee can be liable even though reasonable care is taken with the goods. A bailment for mutual benefit will usually be found when the bailee takes possession of the goods as an incident to the bailee’s business, even if no consideration is received.

Submission/Holding Forms

Rather than relying on the law pertaining to bailment, artists may wish to protect their art by use of a submission/holding form. The following discussion should be prefaced by the observation that the concern about loss of physical art and damages for such loss will be far less significant if the photography or other art is in digital form,

The American Society of Media Photographers (ASMP) developed a delivery memo for its members to have signed by the recipient of photographic positives or transparencies. The contract provides for the recipient to have the liability of an insurer as to submitted materials while either in the recipient’s possession or in transit. Other provisions require that the recipient: make any objections to the terms of the delivery memo within ten days; pay a fee for the recipient’s keeping materials beyond fourteen days; not use the materials without an invoice transferring rights in the work; pay a specified amount per transparency in the event of loss or damage (often set at $1,500 per transparency); not project any transparencies; and submit to arbitration.

The setting of damages in advance is a frequent practice to avoid the necessity of extensive proofs to establish proper damages at trial. The courts will normally enforce such provisions for damages, known as liquidated damages, as long as damages would be difficult to establish and the amount specified is not unreasonable or a penalty. Rather than using $1,500 as a standard minimum figure, it would be wise to list a value for each photograph. This will avoid any risk of a court concluding that the $1,500 figure is excessive as to some transparencies.

In any case, other artists may wish to follow the lead of ASMP whenever work leaves their hands. Certainly, however, the artist entering into a bailment relationship should avoid a contract that lowers the reasonable care usually required to safeguard the artist’s work.

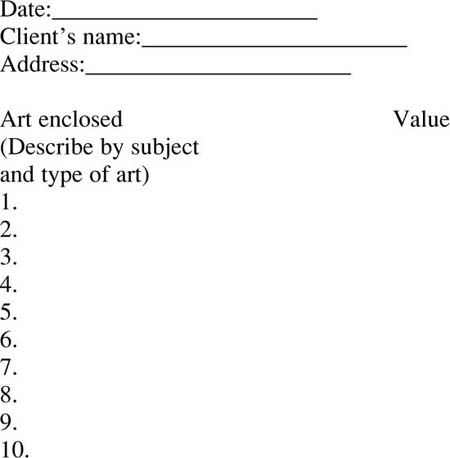

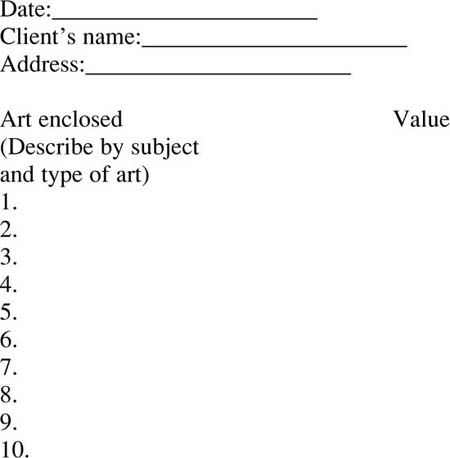

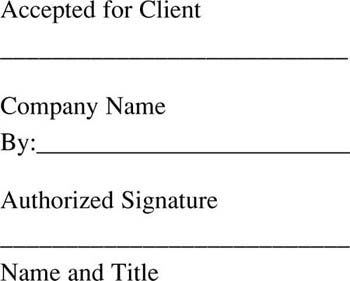

Model Submission/Holding Form

This model form can be adopted by any artist for use when work is to be submitted to and held by a client.

Model Submission/Holding Form

Artist’s Letterhead

Subject to all terms and conditions on reverse side.

[Model Holding/Submission Form—reverse side]

Terms and Conditions

The submitted art is original and protected under the copyright law of the United States. This art is submitted to the client in confidence and subject to the following terms and conditions:

1. Acceptance. Client accepts the listing and value of art submitted as accurate if not objected to in writing by immediate return mail. Any terms of this form not objected to in writing within ten days shall be deemed accepted.

2. Copyright. Client agrees not to copy or modify directly or indirectly any of the art submitted, nor will client permit any third party to do any of the foregoing. Reproduction shall be allowed only upon Artist’s written permission specifying usage and fees.

3. Return of Art. Client agrees to assume responsibility for loss, theft, or damage to the art while held by Client. Client further agrees to return all art by bonded messenger, air freight, or registered mail. Reimbursement for loss, theft, or damage to each piece of art shall be in the amount of the value entered for that piece. Both Client and Artist agree the specified values represent the value of the art.

4. Holding Fees. Art held beyond ______ days incurs the following daily holding fees :________________________________ [Enter the holding fees for each piece of art for the categories of art submitted.]

5. Arbitration. Client and Artist agree to submit all disputes hereunder in excess of $_______________ [Enter the maximum amount that can be sued on in Small Claims Court, since this is usually the quickest remedy.] to arbitration in ______________________ [Enter the Artist’s city and state.] under the rules of the American Arbitration Association. The arbitrator’s award shall be final and judgment may be entered on it in any court having jurisdiction thereof.

The artist who sells original art seldom benefits from appreciation of the art in the future. Because of this, in 1920, France created the droit de suite, a right of artists to share in the proceeds from sales of their work. The legislation was prompted in part by a Forain drawing showing two children dressed in rags looking into an expensive auction salesroom and saying, “Look! They’re selling one of daddy’s paintings.”

The measure, later incorporated in the copyright provisions under the law of March 11, 1957, was a response to the stereotyped image of the artist living in penury while works created earlier sold for higher and higher prices. The droit de suite lasts for the term of the copyright, during which time the proceeds benefit the artist’s spouse and heirs. The droit de suite applies to original works when sold either at public auction or through a dealer, although the extension of the droit de suite to dealers by the law of March 11, 1957, appears not to have been followed or enforced. The droit de suite is collected when the price is over ten thousand francs. The rate is 3 percent upon the total sales price, not merely the profit of the seller. Artists utilize S.P.A.D.E.M. (Société de la Propriété Artistique, des Dessins et Modèles), an organization like ASCAP, to collect proceeds due under the droit de suite. S.P.A.D.E.M., by reciprocal agreements with similar organizations, also receives proceeds due its artists from sales of work in Belgium and West Germany.

The droit de suite is payable to a foreign artist if a French artist could collect a similar payment in the country of the foreign artist. Despite some commentary to suggest that U.S. artists should be able to collect the droit de suite in France, it appears that U.S. artists are not entitled to the droit de suite because the United States offers no such right to foreign artists. Foreign artists can collect the French droit de suite in any case if such artists have resided in France for five years, not necessarily consecutively, and have contributed to the French life of the arts. This survey covers only the French law, of course, and the laws of other countries with rights similar to the droit de suite can vary significantly. A right to such proceeds exists in some form in countries as diverse as Algeria, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Congo, Costa Rica, Equador, Germany, Guinea, Holy See, Hungary, Italy, Ivory Coast, Luxembourg, Madagascar, Mali, Morocco, Peru, Philippines, Portugal, Senegal, Spain, Tunisia, Turkey, and Uruguay.

Resale Proceeds Right

The French droit de suite has at least been discussed for the United States under the designation of a resale proceeds right. Such a right would require the payment back to the artist of a certain percentage of either proceeds or profits from subsequent sales of the artist’s work. The Visual Artists Rights Act required the Register of Copyrights, in consultation with the Chair of the National Endowment for the Arts, to conduct a study on the feasibility of implementing resale royalties. That report did not strongly support resale royalties, so national resale royalty legislation appears unlikely at this time.

California has taken the lead in this area by enacting a 5 percent resale proceeds right for artists. Whenever an original painting, sculpture, drawing, or original work of art on glass is sold in California or sold anywhere by a seller who resides in California, the artist must be paid 5 percent of the gross sale price within ninety days of the sale. This right may not be waived by the artist, although a percentage higher than 5 percent may be used. For resale proceeds to be payable, however, the sale must be at a profit and the price must be $1,000 or more. Also, the artist must be either a citizen of the United States or a two-year resident of California at the time of the resale. The sale must take place during the artist’s life or within twenty years after the artist’s death, if the artist dies after January 1, 1983.

The law excludes from coverage a resale by an art dealer to a purchaser for a period of ten years after the initial sale by the artist to the dealer. This would also exclude intervening resales between dealers. Also, stained glass incorporated in a building is not considered resold when the building is sold.

Monies due the artist for resale proceeds are protected from the dealer’s creditors. If the seller cannot locate the artist within ninety days to make payment, the proceeds are deposited with the California Arts Council. After seven years, if the council has been unable to locate the artist, the proceeds are used to acquire fine art for the Art in Public Buildings program. The law took effect on January 1, 1977, and applies to works sold after that date regardless of when the works were created or first sold. If the seller does not make payment, the artist has the right to bring suit for damages within three years after the date of sale or one year after discovery of the sale, whichever period is longer. The winning party in any suit is entitled to reasonable attorney’s fees as determined by the court.

Challenge to Resale Rights

When the California law was enacted, many people wondered if it might be unconstitutional. A number of arguments were proposed as to why the law should be invalid. Finally, a dealer sold two paintings subject to the provisions of the law and then brought a lawsuit challenging the law’s constitutionality. He argued that the law: (1) is preempted by the copyright law; (2) violates due process; and (3) violates the contracts clause of the Constitution.

The federal district court rejected these assertions and found the law to be valid, stating:

Not only does the California law not significantly impair any federal interest, but it is the very type of innovative lawmaking that our federalist system is designed to encourage. The California legislature has evidently felt that a need exists to offer further encouragement to and economic protection of artists. That is a decision which the courts shall not lightly reverse. An important index of the moral and cultural strength of a people is their official attitude towards, and nurturing of, a free and vital community of artists. The California Resale Royalties Act may be a small positive step in such a direction (Morseburg v. Balyon, 201 U.S.P.Q. 518, aff’d 621 F.2d 972, cert. denied 449 U.S. 983).

Resale Rights Contracts

Private contract can also create an art proceeds right. If an artist and collector agree that there will be a payment back to the artist on subsequent resales, the artist would be able to gain by private bargaining what French artists possess by national legislation. But the Projansky contract, which provides for such an art proceeds right as well as attempting to create moral rights for U.S. artists, has not been widely adopted. The Projansky contract appears on page 117 and is discussed on pages 116–120.