NINETEEN

Basal Iguanodontia

Iguanodon-like ornithopod dinosaurs have been known since the early years of the nineteenth century, following the discovery of Iguanodon (Mantell 1825; see table 19.1). Iguanodon was in fact one of the founding members of Dinosauria (Owen 1842b). Additional taxa have been described since that time, notably Camptosaurus (Marsh 1879c; Hulke 1880b), Zalmoxes robustus (Nopcsa 1902; Weishampel et al. 2003), Dryosaurus (Gilmore 1925b; Janensch 1955), Probactrosaurus (Rozhdestvensky 1966; Lü 1997), Tenontosaurus (Ostrom 1970a; Forster 1990), Ouranosaurus (Taquet 1975, 1976), and Muttaburrasaurus (Bartholomai and Molnar 1981). More recently there has been a considerable increase in the number of taxa referred to this group: Gasparinisaura (Coria and Salgado 1996b), Altirhinus (Norman 1998), Protohadros (Head 1998), Eolambia (Kirkland 1998b), Lurdusaurus (Taquet and Russell 1999), Nanyangosaurus (Xu et al. 2000b), Jinzhousaurus (Wang and Xu 2001a, 2000b), Planicoxa (DiCroce and Carpenter 2001), and Draconyx (Mateus and Antunes 2001), among others, have been added to the list. We have a good understanding of these animals, particularly in the light of the monographic descriptions provided by Gilmore (1909) for Camptosaurus, by Janensch (1955) for Dryosaurus (see also Galton 1977b, 1981b, 1983c), by Taquet (1976) for Ouranosaurus, by Norman (1980, 1986) for Iguanodon, and by Forster (1990a) for Tenontosaurus.

Basal iguanodontians are variable, ranging from small (2–3 m long), lightly built, and by implication active bipeds, represented by Dryosaurus, to large and robust (10–11 m long) facultative quadrupeds such as Iguanodon bernissartensis, with an estimated body mass in excess of 2,500 kg. Other researchers, notably Alexander (1989), have estimated masses as high as 5,000 kg—such large body masses may be applicable to the extremely robust forms such as Lurdusaurus. Basal iguanodontians are widely dispersed geographically and temporally, ranging across both the Northern and Southern hemispheres and found in rocks ranging in age from the Late Jurassic to latest Cretaceous.

Definition and Diagnosis

Iguanodontia is a stem-based taxon defined as all euornithopods closer to Edmontosaurus than to Thescelosaurus. It is diagnosed by the following features: a premaxilla with a transversely expanded and edentulous margin; a predentary with a smoothly convex rostral margin when viewed in dorsal aspect; a deep dentary ramus with parallel dorsal and ventral borders; no evidence of sternal rib ossification; one phalanx lost on manus digit III; a prepubic process that is compressed and blade-shaped.

Anatomy

Skull and Mandible

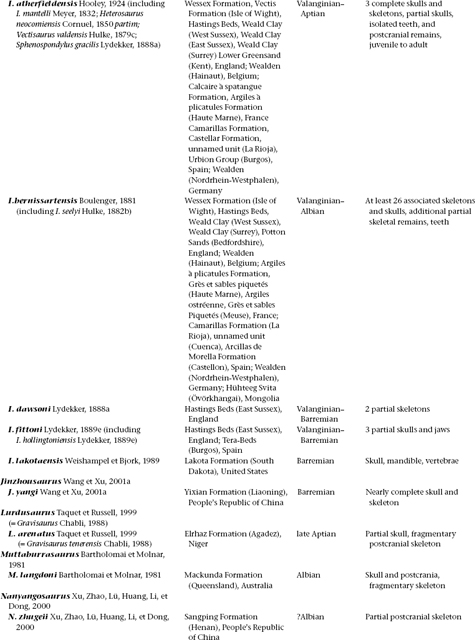

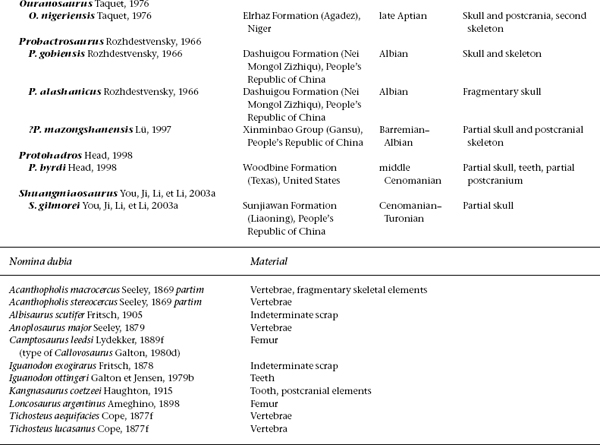

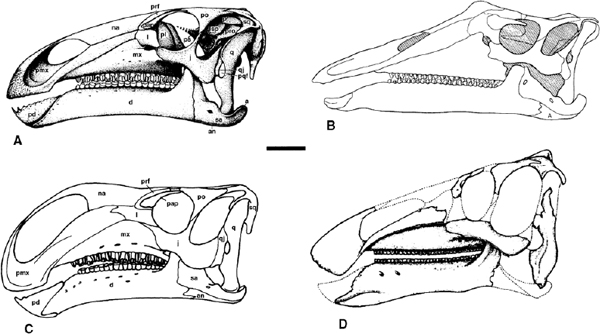

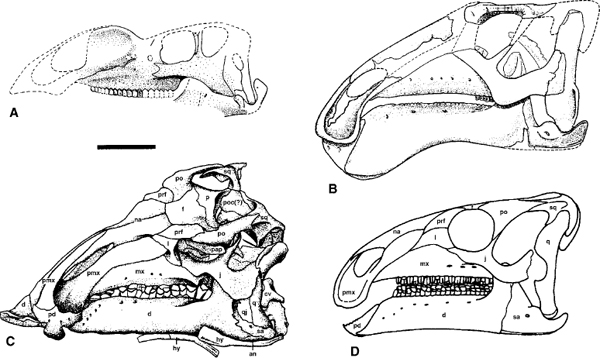

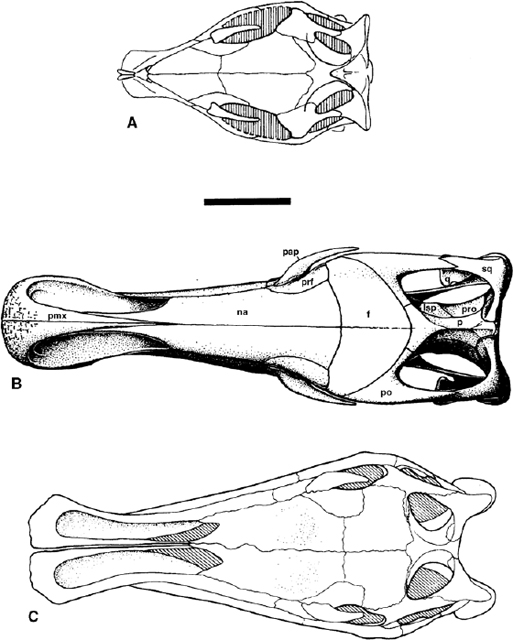

The skull in most basal iguanodontians (figs. 19.1–19.3) is long, laterally compressed, and moderately deep, with a well-proportioned oval supratemporal fenestrae, a prominent, generally circular, orbit (lacking evidence of sclerotic plates), and a large external naris; the lower border of the latter is everted to a varying degree, forming a rim for the broad, toothless, upper beak (rhamphotheca). The exceptions to this general rule are to be found in Dryosaurus (Janensch 1955; Galton 1981b, 1983c) and Zalmoxes robustus (Nopcsa 1902, 1904, 1915, 1928b; Weishampel et al. 2003) in which the skull is proportionally shorter and more compact. The palpebral is generally slender and elongate, often extending chordlike across the orbit. In Dryosaurus altus (Galton 1983c) the palpebral crosses the orbit and contacts the postorbital, thereby enclosing a slitlike supraorbital fenestra. In forms such as Tenontosaurus this bone has been described as fingerlike (Winkler et al. 1997b) and articulated with the prefrontal; this genus is also unusual in exhibiting an orbit that has a roughly rectangular shape—a feature that may also be shared by Zalmoxes (fig. 19.1). Some taxa display an arched palpebral that follows the rostrodorsal margin of the orbit, rather than traversing the orbit itself (fig. 19.2, Iguanodon), whereas in more derived taxa such as Protohadros, Eolambia, and Probactrosaurus, the presence of a palpebral cannot be confirmed at this time. Tenontosaurus (fig. 19.1) has a dorsally expanded maxilla that forms much of the lateral wall of the snout region, whereas in the majority of iguanodontians the maxilla has a lower and more clearly triangular lateral exposure (figs. 19.1–19.3). The external antorbital fenestra and its associated fossa are variable in shape, forming an essentially subcircular external opening in Tenontosaurus (Winkler et al. 1997b, although this was described as slitlike by Ostrom [1970a] for T. tilletti) and is bounded by the lacrimal and maxilla. Unlike basal ornithopods, in which there is usually a well-developed fossa associated with the external fenestra (a feature retained at least in Dryosaurus), this is usually much reduced in iguanodontians and forms a shallow tubular structure rather than an expanded recess (fig. 19.2, Iguanodon); in the most derived nonhadrosaurid iguanodontians (Altirhinus, Protohadros, possibly Probactrosaurus) the external opening of the fenestra is closed by the bones of the snout (Head 1998; Norman 1998).

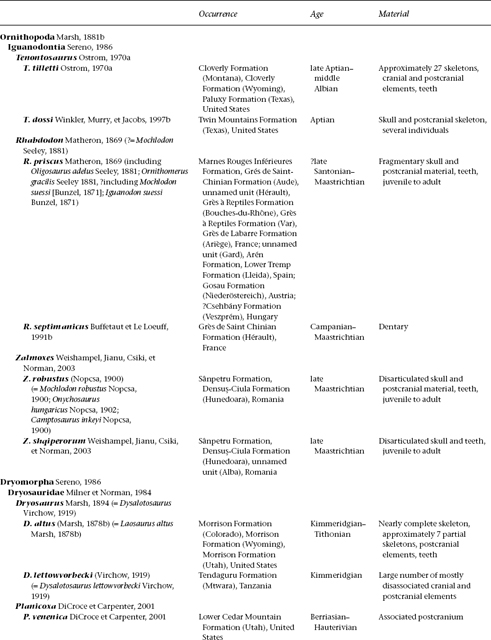

TABLE 19.1

Basal Iguanodontia

The ventral margin of the premaxilla is everted to form a spatulate beak and, although this is edentulous in Tenontosaurus tilletti, shows evidence of one premaxillary tooth in the allied T. dossi (Winkler et al. 1997b). In Zalmoxes (fig. 19.1), the premaxillae are narrow and pointed, and strongly resemble the form seen in basal ornithopods such as Hypsilophodon, whereas Dryosaurus has premaxillae that are only modestly expanded (fig. 19.1). In more derived forms the development of the premaxillary beak becomes pronounced (figs. 19.1–19.3). The caudolateral process of the premaxilla extends backward to meet and overlap the lacrimal in the majority of cases, and in so doing separates the maxilla and nasal externally. The dorsal process formed by the conjoined premaxillae forms a tapering wedge between the rostral ends of the nasals immediately above the nasal opening, although in Dryosaurus lettowvorbecki (Janensch 1955) this process is unusually short and may have failed to reach the nasals (fig. 19.1).

The rostral end of the maxilla is bifurcate in iguanodontians. In the case of Tenontosaurus, Weishampel (1984c) reported the presence of a rostromedial process of the maxilla that fitted into the caudomedial edge of the conjoined premaxillae. Whether the rostral maxilla was truly bifurcate, as in Dryosaurus (Janensch 1955) and other iguanodontians (Norman 1986, 1996), or retains the configuration seen in euornithopods such as Hypsilophodon and Thescelosaurus is uncertain. In the case of the apparently more derived Zalmoxes, the rostral end of the maxilla is not bifurcate and more nearly resembles the form seen in thescelosaurs and more basal euornithopods. Behind this region in the most basal forms (Tenontosaurus and Zalmoxes) the nasal and maxilla retain sutural contact on the exterior of the snout (fig. 19.1). The number of tooth positions (alveoli) in the maxilla varies significantly among iguanodontians. In general there are fewer tooth positions in more basal forms (about 10–12 is the minimum in the range, seen in forms such as Tenontosaurus and Zalmoxes), rising numbers are seen in forms such as Dryosaurus (13–17), Camptosaurus (14–16), whereas more derived forms, such as Iguanodon, range to near 30 and Eolambia possesses at least 33.

Each nasal is long, narrow, and arched transversely, meeting and usually overlapping the prefrontal and, in some instances, the lacrimal as well, immediately in front of the orbital opening. The prefrontal and lacrimal border the orbit; the former sends a fingerlike process backward to rest in steplike grooves on the surface of the frontal. The lacrimal is a large bone (much obscured by the surrounding snout bones) that runs forward and lines the lateral part of the nasal cavity.

FIGURE 19.1. Skulls of: A, Tenontosaurus tilletti; B, Zalmoxes robustus; C, Dryosaurus lettowvorbecki; D, Camptosaurus dispar. Scale = 5 cm. (A from Sues and Norman 1990; B Weishampel et al. 2003; C from Sues and Norman 1990; D from Norman and Weishampel 1990.)

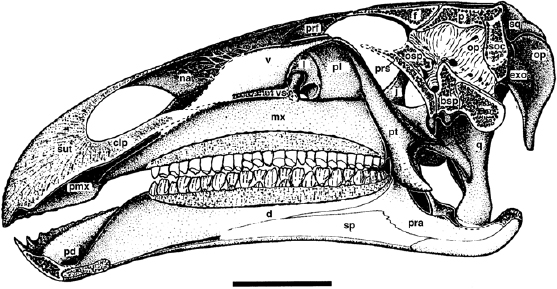

The frontals form a broad portion of the skull table (fig. 19.4) but, except in Dryosaurus, have a comparatively short exposure on the orbital margin (completely lost in Jinzhousaurus, Wang and Xu [2001a, 2001b]) and are tightly sutured to each other along the midline. The frontals form a strong, deep, curved (and usually interdigitate) suture with the parietals. The frontal plate in iguanodontians is flat, rather than arched as is the case in more basal euornithopods. The parietals are fused into a single saddle-shaped plate that bears a median sagittal crest; this plate is generally indented (notched) along its occipital edge where it meets the ascending process of the supraoccipital. The rear portion of the skull table forms an essentially rectangular open frame, the outer edges of which are formed by the postorbital-squamosal bars that enclose the large ovoid supratemporal fenestrae on either side (separated by the parietal shield and its sagittal crest). In some instances the upper temporal arches converge toward the occipital surface (as in Dryosaurus lettowvorbecki, Iguanodon atherfieldensis, and Ouranosaurus nigeriensis, fig. 19.4) but this is a variable trait within nonhadrosaurid iguanodontians. The general proportions of this region of the skull roof may vary slightly but the supratemporal fenestrae are consistently oval with their long axes parallel to the long axis of the skull. The shaft of the quadrate is nearly straight or slightly curved and the dorsal head of the quadrate is often supported by a vertical buttress. The lateral wing of the quadrate connects with the jugal arch and is embayed for the attachment of the quadratojugal. The embayment is shallow in some instances (Tenontosaurus, Rhabdodon, Camptosaurus, Eolambia, and Protohadros) and contains a tightly fitting quadratojugal. In other forms the quadrate is more acutely notched (e.g., Dryosaurus and Iguanodon) and in this instance the quadratojugal spans the upper and lower edges of the embayment, and enclosing a distinct paraquadrate foramen. In Tenontosaurus the quadratojugal is punctured by a large fenestra; this is an unusual feature also found in some basal ornithopods (Hypsilophodon, see Galton 1974a).

The bones of the palate of iguanodontians have been described in varying detail, depending on preservation. Those of Tenontosaurus dossi have been described in some detail (Winkler et al. 1997b), but were not illustrated. The description is similar in many respects to that of most ornithopods and ornithischians generally (Norman 1980, 1986). In species of Iguanodon (fig. 19.5) and Altirhinus (Norman 1998) the vomers form deep, thin plates that are fused along their ventral edges. The rostral portion contacts a median, slotlike recess between the premaxillae. From here, the vomers form a keel-like blade that bisects the nasal cavity, extending along the midline as far as the level of the lacrimal. The dorsal portion of each vomer consists of a deepening plate that diverges from its neighbor, thereby forming the medial septal walls of the nasal cavity. The distal extremity of each vomer extends dorsally in a rising arch to meet or lie adjacent to the rostral extremity of the pterygoid and the dorsal margin of the palatine.

The palatine is rhomboidal in outline (when viewed dorsolaterally) and forms the lower part of the medial wall of the orbit. The ventral portion articulates with the caudomedial part of the body of the maxilla. From here, the palatine rises in a smooth arch toward the midline just beneath the frontal-nasal suture. The rostral edge of the palatine is smoothly curved and has a rounded edge. The medial edge, by contrast, is sutured to the narrow, obliquely inclined rostral process of the pterygoid.

FIGURE 19.2. Skulls of: A, Iguanodon atherfieldensis; B, Ouranosaurus nigeriensis; C, Altirhinus kurzanovi; D, Eolambia caroljonesa. Scale = 10 cm. (A from Norman et al. 1987; B from Taquet 1976; C from Norman 1998; D from Kirkland 1998b.)

FIGURE 19.3. Skulls of: A, Muttaburrasaurus langdoni; B, Protohadros byrdi; C, Jinzhousaurus yangi; D, Probactrosaurus gobiensis. Scale = 10 cm. (A from Bartholomai and Molnar 1981; B from Head 1998; C from Wang and Xu 2001b; D from Norman 2002.)

The rostral portion of the pterygoid is narrow, thin, and twisted axially. Toward the body of the pterygoid, the ventral edge is sutured to the oblique margin of the maxilla, and this area is further bound to the maxilla by the straplike ectopterygoid. Behind the basal articulation at the center of the pterygoid, the central plate of the pterygoid develops into a deep, thin sheet of bone that is forked and overlaps the medial side of the pterygoid ramus of the quadrate. Ventrally and beyond the end of the maxilla, the pterygoid develops a broadly curved pterygoid flange, the site of attachment of M. pterygoideus dorsalis.

FIGURE 19.4. Skulls in dorsal aspect: A, Dryosaurus lettowvorbecki; B, Iguanodon atherfieldensis; C, Ouranosaurus nigeriensis. Scale = 10 cm. (A from Sues and Norman 1990; B from Norman et al. 1987; C from Taquet 1976.)

The ectopterygoid is adequately known only in Iguanodon (Norman 1980, 1986). It is a narrow strap of bone that lies in a recess on the lateral surface of the maxilla. The rostral end fits against the medial side of the jugal adjacent to the jugal-maxilla suture, while the body of the ectopterygoid extends across the maxilla and on to the pterygoid; whether it forms part of the lateral margin of the ventral pterygoid flange or simply helps to lock the pterygoid to the maxilla cannot presently be determined. Hadrosaurid iguanodontians exhibit an abbreviated ectopterygoid that entirely fails to make contact with the jugal (Lambe 1920).

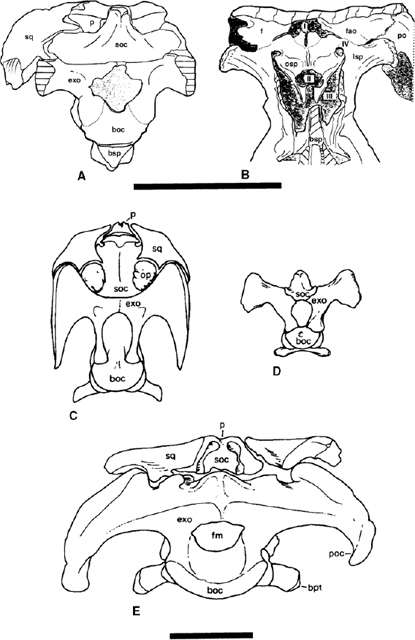

The braincase of Tenontosaurus dossi (fig. 19.7) has been described by Winkler et al. (1997b) and comprises a large basioccipital that forms a crescentic condyle, while the exoccipitals form condylids on the dorsolateral corners. The main body of the basioccipital is narrow before reexpanding at the contact with the basisphenoid and basal tubera; on the rostrolateral surface of the basal tubera, the basisphenoid forms a large oblique plate with a rugose surface (crista tuberalis), which has been interpreted (Norman 1984a; Weishampel 1984c) as an area for attachment of part of the constrictor dorsalis musculature (or its ligamentous derivative). The back of this flange acts as a groove for the passage of the palatine branch of the facial nerve (c.n. VII) before it enters the carotid canal. The rostral part of the basisphenoid is damaged. The occipital aspect of the braincase is dominated by the supraoccipital (fig. 19.6), which forms a broad, inclined plate shaped like an inverted T with the prominent ascending process abutting the undersurface of the parietal plate. On either side the wings of the supraoccipital spread laterally to meet the inner surfaces of the squamosals dorsal to the paroccipital process (between the supraoccipital and parietal plate on either side of the nuchal ridge is a space that probably represents the remnant of the posttemporal fenestra). The supraoccipital plate extends ventrally as a transversely concave sheet that is apparently draped over the exoccipitals, but the latter meet in the midline to exclude the supraoccipital from the boundary of the foramen magnum. The overall similarity in the proportions of the occiput to the configuration in basal ornithopods is striking. In addition, the supraoccipital has a significant rostral extension into the dorsolateral walls of the braincase along the suture between the parietal and the prootic-opisthotic complex. The detailed morphology of the supraoccipital is not often discernible; however, in this respect the supraoccipital is as extensive as that found in some hadrosaurids (Horner 1992) and basal ornithopods such as Hypsilophodon (Galton 1974a). The exoccipitals and opisthotics are fused on either side to form large, hooked paroccipital processes, and these are in turn over-lapped by the prootic in archosaurian fashion; between these latter bones and the ventral braincase elements there is a horizontal groove punctured by the cranial nerves, blood vessels, and auditory apparatus (figs. 19.8, 19.9). Rostrodorsally the prootic contacts the laterosphenoid, which, in turn, swings laterally and dorsally, contacting the undersurface of the parietal and frontal before terminating in a rounded capitate process that meets the frontal and medial face of the postorbital. Unusually, in nonhadrosaurid ornithopods, the orbitosphenoid-sphenethmoid plate is preserved, spanning the gap between the laterosphenoids at the front of the braincase; the orbitosphenoid and sphenethmoid bones contact and fuse with the frontal dorsally and the laterosphenoids laterally and form a reticulate arrangement through which the olfactory lobes and cranial nerves exited from the front of the braincase.

FIGURE 19.5. Reconstructed sagittal section through the skull of Iguanodon atherfieldensis indicating the palate bones. Scale = 10 cm. (From Norman et al. 1987.)

The neurocranial region in more derived iguanodontians (Norman 1980, 1986; Galton 1983c) is firmly fused and consists of lateral walls comprising: the orbitosphenoid, the laterosphenoid, the prootic, the opisthotic, and the exoccipital. The crista prootica extends across the prootic and the opisthotic to the base of the paroccipital process, marking the attachment site of M. levator pterygoideus (fig. 19.7B). Ventrally, the braincase comprises the parasphenoid, the basisphenoid, and the basioccipital. The shallowly etched surface between the traces of the maxillary and mandibular branches of c.n. V along the lateral wall of the basisphenoid marks the site of attachment of either the M. protractor pterygoideus or an equivalent ligament that extended on to the dorsomedial edge of the pterygoid. The basipterygoid process of the basisphenoid is low and oblique (Norman 1980, 1986; Weishampel 1984c; Norman et al. 1987), and the occipital condyle portion of the basioccipital is set on a short, but distinct, neck and varies in size and shape from species to species. In some taxa, it is almost heart-shaped in occipital view (Ouranosaurus), whereas in others it may be globular (Iguanodon).

The occiput is formed principally of the massive laterally projecting paroccipital processes; between these, the foramen magnum is surrounded by the exoccipitals, which together form a horizontal bar separating the foramen magnum from the more dorsally positioned supraoccipital (fig. 19.6), unlike what is found in Dryosaurus and Camptosaurus. The supraoccipital is not well delimited, partly because it is lodged more dorsally in a recess in the occipital surface beneath the parietals and between and below the shoulders of the occiput formed by the squamosals and exoccipitals. It is thin and poorly ossified in Iguanodon atherfieldensis (Norman 1986) but prominent in I. bernissartensis (Norman 1980). Ouranosaurus nigeriensis has a lower and broader braincase than any other iguanodontian, more similar in its proportions to those seen in some hadrosaurids. All the bones within the occiput are fused, and it is reported that the supraoccipital is excluded from the foramen magnum as in all the more derived iguanodontians (Taquet 1976).

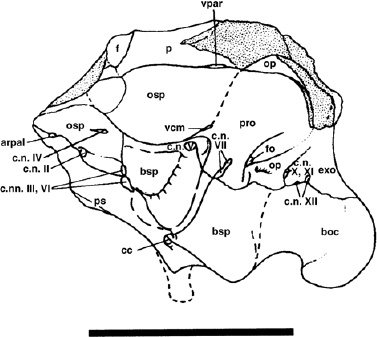

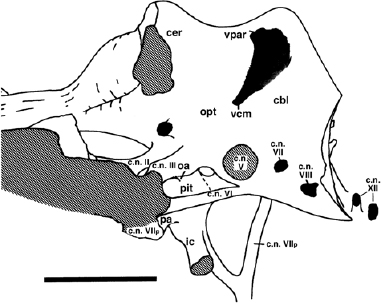

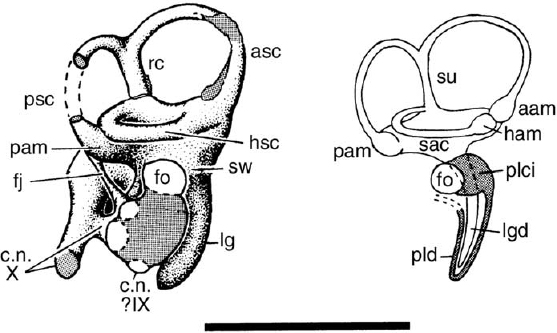

Internally, the endocranial cavity of Iguanodon (fig. 19.8) is similar to that seen in hadrosaurids (Ostrom 1961a; Norman and Weishampel 1990). The rostral telencephalic region is broadly expanded, followed by a constriction accommodating the mesencephalon and finally the dorsoventrally expanded metencephalic and myelencephalic region that tapers caudally toward the foramen magnum (fig. 19.8). The area immediately beneath the mesencephalon is made more complex by the presence of vessels leading to and from a large sinus on the dorsolateral wall of the endocranial cavity. The bulbous telencephalon (composed mainly of the paired cerebral hemispheres) tapers rostrally to the coronal sulcus, a constricted region that marks the rostral termination of the cerebral expansion and separates this part of the brain from the olfactory lobes. Beneath the broadly expanded area of the cerebral hemispheres, there is a well-preserved pituitary fossa and indications of the paths of the associated vessels and nerves. All 12 cranial nerves are present (Norman and Weishampel 1990). The osseous labyrinth is also known in Iguanodon (fig. 19.9). The labyrinth is notable for the small size of the sacculus and the elongate lagena, a combination of features that is similar to that in many other dinosaurs.

FIGURE 19.6. A, B, Occipital and rostral views of the braincase of Tenontosaurus dossi; C, occipital view of Iguanodon atherfieldensis; D, occiputal view of Camptosaurus dispar; E, occiputal view of Ouranosaurus nigeriensis. Scale = 10 cm. (A, B from Winkler et al. 1997b; C, D from Gilmore 1909; E from Taquet 1976.)

The predentary of Tenontosaurus is deep and wedgelike in lateral aspect and horseshoe-shaped in dorsal view; it has a single, broad ventral process (Winkler et al. 1997b), which is similar in overall shape to that seen in more basal euornithopods; its sharp dorsal margin bears toothlike projections near the midline. In all more derived iguanodontians (where known) the predentary exhibits a different morphology: the ventral process, which underlies the dentary symphysis, is strongly bifurcated, so that one flap on each side is lodged against the undersurface of the dentary, lateral to the symphysis. The degree to which each toothlike denticula is developed along the occlusal edge of the predentary also varies; the predentary of Zalmoxes is non-denticulate, as is the predentary in Dryosaurus (this bone has not been described in Camptosaurus). More derived iguanodontians, when well-preserved, show the presence of denticulate predentaries, which vary from sharply pointed (Iguanodon spp.) to more lobate (Probactrosaurus), reminiscent in the latter case of those seen in the predentaries of hadrosaurids.

FIGURE 19.7. The braincase of Iguanodon cf. atherfieldensis in left lateral view. Scale = 10 cm. (From Norman 1986.)

FIGURE 19.8. Endocranial cast of Iguanodon sp. from the Wealden of Sussex, England, in left lateral view. Scale = 10 cm. (From Norman 1977.)

FIGURE 19.9. Matrix-filled bony labyrinth of Iguanodon sp., and sketch of the soft tissues it contained. Scale = 5 cm. (From Norman 1977.)

The dentary has a beveled rostral tip with a groove dorsally; this structure fit between the upper occlusal ramus of the predentary and its lower (midline) ventral process to create a stable symphyseal junction. The main body of the dentary is stout, with, in most cases, parallel dorsal and ventral edges, and contains a variable number of tooth positions (as a general rule fewer are found in more basal members of Iguanodontia: approximately 12 in the most basal taxon Tenontosaurus, 10 in Zalmoxes, and 12–14 in Dryosaurus and Camptosaurus). More derived iguanodontians have tooth position counts that range into the high 20s. Caudally the dentary develops a distinct coronoid process from its dorsolateral edge, which is supported by the bladelike rostral portion of the surangular. The degree of development and overall prominence of the coronoid process varies considerably across nonhadrosaurid iguanodontians. In more basal forms (Tenontosaurus, Zalmoxes, Dryosaurus, Camptosaurus dispar, Camptosaurus hoggi [Norman and Barrett 2003]) the coronoid process is elevated, but oblique, relative to the long axis of the dentary ramus. More derived forms exhibit a more perpendicular and larger coronoid process, and in the most derived forms identified (Eolambia, Protohadros, Probactrosaurus) the coronoid process is not only highly elevated, but also offset strongly laterally and rostral relative to the distal part of the dentition; the coronoid process also has a laterally compressed and rostrally expanded apex—a condition similar to that seen in hadrosaurids.

The surangular of Tenontosaurus is the largest of the postdentary bones and bears a prominent tablike process lateral and rostral to the quadrate cotylus (as also seen in Zalmoxes robustus and some basal ornithopods, e.g., Bugenasaura). There is a prominent accessory surangular foramen (possibly a remnant of the external mandibular fenestra seen in more basal ornithischians) close to the dentary suture beneath the coronoid process. The surangular foramen sensu stricto is present immediately beneath and rostral to the everted lip of the surangular that buttresses the lateral edge of the jaw joint. The dentary is long and transversely thick, more so caudally, and the alveoli are positioned along the extreme medial edge. The teeth form a more or less straight array mesially, but toward the distal end of the series the tooth rows curve laterally toward the base of the coronoid process; however, in more derived iguanodontians the distal portion of the dentition is straight, passes medial to the coronoid process, and is separated from the latter by a shelf (Probactrosaurus). There can be a diastema between the predentary and the tooth-bearing portion of the dentary, variably developed among basal iguanodontians (short or absent in Iguanodon lakotaensis and I. bernissartensis; long in I. atherfieldensis, Ouranosaurus nigeriensis, Eolambia, and Protohadros; but short in basal hadrosaurids such as Telmatosaurus [Weishampel et al. 1993] and [Bactrosaurus Godefroit et al. 1998b]). The surangular is large and well exposed on the lateral surface of the mandible. The rostral portion of this bone slots into a sleeve formed by the dentary. Dorsally the surangular develops a slot-groove suture with the dentary and coronoid (Norman 1980, 1986). Behind the coronoid process the surangular drops sharply and broadens to form the major part of the jaw joint. Here the surangular consists of a broad cup-shaped depression that receives the convex lateral portion of the mandibular condyle of the quadrate. Behind the joint there is a retroarticular process, the medial side of which bears a shallow depression for the articular bone. Rostral and ventral to this area, there are further depressions for the prearticular, angular, and splenial. The surangular forms the lateral margin of the adductor fossa.

The articular is small and poorly ossified, occupying a lozenge-shaped recess between adjacent postdentary bones (surangular, prearticular, angular); it contributes a little to the medial part of the jaw joint. The prearticular serves (along with the surangular) to sandwich the articular and forms the medial border of the glenoid. Rostrally, the prearticular is thin where it forms the medial margin of the adductor fossa and sends a spur toward the base of the coronoid process. Farther rostrally, the prearticular is long and tapering beneath the arcade of special foramina medial to the dorsal part of the mandibular canal; it is overlain by the splenial, which lies ventral to the prearticular and with the latter covers the mandibular canal. The rostral extent of the splenial is not yet known. The splenial lies beneath the prearticular and contacts the surangular by means of a lateral, horizontal shelf (Norman 1980). The angular lies along the ventral edge of the mandible and is visible laterally. Although variable among genera, the angular is a long, thin bone that sits in a recess on the ventral surface of the surangular. It contacts the splenial medially along a butt suture.

The coronoid attaches to the medial side of the apical portion of the coronoid process of the dentary. Again, this bone is visible in lateral view as a small corona above the dentary portion of the process in several iguanodontians, and an isolated coronoid was tentatively identified in Ouranosaurus (Taquet 1976). No discrete coronoid bone has been identified in lower jaws of more derived iguanodontians (Altirhinus, Eolambia, Protohadros, Probactrosaurus) and none has been reported in hadrosaurids. The caudal edge of the coronoid is involved (at least in species of Iguanodon) in a complex suture between the dentary and surangular (Norman 1986). In addition, better-preserved material of I. atherfieldensis shows that there is a ventral extension of this bone that extends medial to the mesial alveoli and gradually tapers rostrally medial to the alveolar parapet. A similar arrangement was recognized much earlier in ceratopsids (Brown and Schlaikjer 1940a), and the bone extending along the medial wall of the dentary was named the intercoronoid. This intercoronoid, however, may be a ventral extension of the coronoid bone rather than a separate ossification; a similar structure has been identified in Scelidosaurus (Norman, in prep.) and Lesothosaurus (Sereno 1991b).

FIGURE 19.10. Hyoid bones of Ouranosaurus nigeriensis: A, dorsal view; B, lateral view. Scale = 5 cm. (After Taquet 1976.)

Portions of the hyoid apparatus are commonly preserved between the mandibles in undisturbed skulls (fig. 19.10). The paired ceratobranchials are elongate curved rods tapering toward one end. The end of the ceratobranchial is abruptly truncated and sometimes preserves the articular surface for adjacent parts of the hyoid.

The crowns of both the maxillary and dentary teeth are mesiodistally expanded and buccolingually compressed, presenting a flattened, shield-shaped face subdivided by enamel ridges buccally and lingually, respectively. There is a general trend associated with the pattern or ridges on the shieldlike surface of the crowns. Maxillary crowns (fig. 19.11) of basal forms have patterns of low ridges in a parallel or divergent array running from root to apex, the ridges themselves ending at marginal denticles; the dentary crowns (fig. 19.11), in contrast, are marked by a generally submedian, prominent primary ridge running from the base of the crown to its apex and a variable number of subsidiary ridges. More derived iguanodontians exhibit maxillary teeth that show a single, submedian, prominent primary ridge and few subsidiary ridges, whereas the dentary crowns show a pattern of much less prominent ridges, usually a low but distinct primary ridge that ends at the apex of the crown, and normally at least one secondary ridge situated mesial to the primary ridge. In the most derived iguanodontians the maxillary and dentary crowns become generally narrower and more symmetrical, converging on the simplified, diamond-shaped crown face morphology seen in hadrosaurid iguanodontians.

In basal iguanodontians a veneer of enamel covers the entire crown of both maxillary and dentary teeth, but is thicker and distinctively ridged on the lingual surface of the dentary and buccal surface of the maxillary crowns, respectively. In more derived, but nonhadrosaurid, iguanodontians the enamel surface of the crown is found to be more restricted so that maxillary crowns are only enameled buccally and dentary crowns are corresponding enameled lingually. The margins of all crowns are ornamented by enameled denticles. More basal iguanodontians display denticles that are simple and tongue-shaped when the tooth is viewed edge on; in more derived forms the edges of the denticles are mammillated to varying degrees, as originally recognized by Owen (1840). Denticles and mammillations are progressively eliminated in hadrosaurid dental batteries.

FIGURE 19.11. A, B, Maxillary (buccal view) and dentary (lingual view) teeth of Dryosaurus lettowvorbecki; C, D, dentary (lingual view) and maxillary (buccal view) teeth of Altirhinus kurzanovi; E, dentary (lingual view) tooth of Probactrosaurus gobiensis. Scale = 1 cm. (A, B from Sues and Norman 1990; C, D from Norman 1998; E from Norman 2002.)

Tooth replacement patterns vary slightly among taxa. Most iguanodontians show evidence of one functional crown in each jaw that is supported by a single replacement crown growing medial to its base within the same alveolus. However in the most derived forms known to date (Equijubus [You et al. 2003b], Altirhinus [Norman 1998], Protohadros [Head 1998], Eolambia [Kirkland 1998b], Probactrosaurus [Norman 2002]), a second replacement crown is found in the dentary and maxillary batteries. This overall increase in the number of teeth in the dentition and concomitant close packing of the crowns within the dentition together converge on the replacement pattern and dental-battery construction exhibited by hadrosaurid iguanodontians.

Postcranial Skeleton

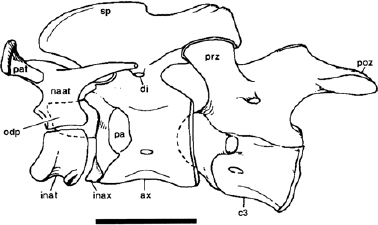

AXIAL SKELETON

The vertebral column of the basal iguanodontian Tenontosaurus comprises 12 cervical, 16 dorsal, 5 sacral, and between 60 and 65 caudal vertebrae (Ostrom 1970a; Forster 1990a). The cervical vertebrae are weakly opisthocoelous and have constricted sides and thick, rugose ventral keels (Forster 1990a). The neural arches bear short, stout neural spines that are narrow and pointed cranially, but become thicker, taller, and broader along the series. The centra of the dorsal vertebrae are amphiplatyan and have subcircular articular ends. The robust neural arches are low (never much taller than the combined height of centrum + neural arch platform) and bear stout zygapophyses, which have articular facets inclined at about 45° throughout the dorsal column. The cranial sacral centra fuse to each other and their sacral ribs in adult individuals of T. tilletti (Forster 1990a) and T. dossi (Winkler et al. 1997b); in young individuals these bones remain unfused. The sacral series incorporates an additional dorsosacral vertebra. The tail accounts for two-thirds of the length of the body in Tenontosaurus (fig. 19.13A). The proximal caudal vertebrae have short, deep, and broad centra and narrow neural spines of moderate height that are forwardly curved; the latter become straighter and rapidly become longer along the series. The chevrons mirror the neural spines, quickly increasing in length and even exceeding the length of the neural spines farther along in the series.

FIGURE 19.12. First three cervical vertebrae of Iguanodon atherfieldensis in articulation. Scale = 5 cm. (From Norman et al. 1987.)

Epaxial ossified tendons are found along almost the entire dorsal series, across the sacrum, through to the end of the tail; they are of variable length and vary in orientation, and some bifurcate or have a flattened appearance (Forster 1990a); similar features have been reported in Iguanodon (Norman 1986) and Hypsilophodon (Galton 1974a). The tail of Tenontosaurus is unusual for iguanodontians in that it is also enclosed by dense bundles of epaxial and hypaxial ossified tendons for most of its length (Ostrom 1970a; Forster 1990a). Hypaxial tendons begin at about the fifth or sixth caudal vertebra and extend to the distal extremity of the tail, where they form dense overlapping bundles that completely enclose and obscure the caudal vertebrae and chevrons. In T. dossi some of the tendons in the tail are also reported to be thin and fan-shaped (Winkler et al. 1997b).

The axial skeleton of Dryosaurus (fig. 19.13B) is not significantly different from those of a variety of basal euornithopods, such as Hypsilophodon (Janensch 1955). The vertebral count is described as 9 cervicals, 15 dorsals, 6 sacral vertebrae, and an indeterminate number of caudals (30+). This count is similar to that recorded in Camptosaurus (Gilmore 1909), 9: 15–16: 5: 45+, which suggests that the high vertebral count recorded in Tenontosaurus is an apomorphy of the genus. In Camptosaurus (fig. 19.14A) the cervical centra form low cylinders with a ventral keel and become progressively more opisthocoelous along the series (commencing with essentially flat-faced centra cranially). The cranial face of the centra of more caudal cervicals also develops a low convexity. Dorsals are similar in general shape, but have a narrower ventral keel and are amphiplatyan. The transverse processes are long and oblique cranially in the series and have an angled, essentially rhomboid, tall median neural spine, which becomes progressively longer, thicker, and more upright in later members of the series. As in Tenontosaurus the cranial members of the sacral series fuse earlier than the late members during ontogeny. Ossified tendons are present epaxially in all of the more derived iguanodontians, but no hypaxial bundles similar to those described for Tenontosaurus (and a variety of more basal euornithopods) have been reported. The epaxial ossified tendons adopt a latticelike arrangement in some instances along the caudal dorsal series in Camptosaurus (Gilmore 1925b) and in more derived iguanodontians (Iguanodon) in which the neural spines are tall and provide a span for a lattice to form (fig. 19.14B).

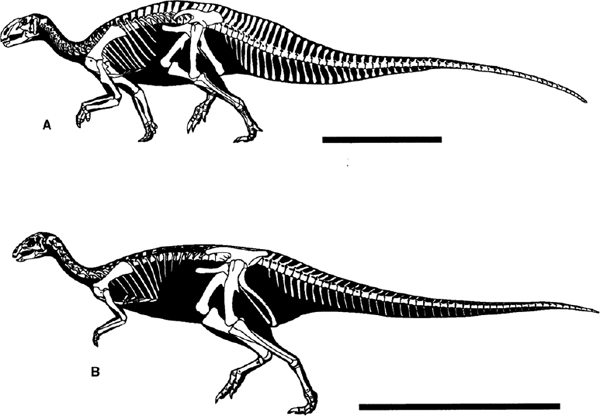

FIGURE 19.13. Skeletal reconstructions: A, Tenontosaurus tilletti; B, Dryosaurus altus. Scale = 1 m. (Courtesy of and copyright by G. S. Paul.)

In more derived iguanodontians vertebral counts, when known, are consistent—Iguanodon atherfieldensis: 10 or 11 cervical vertebrae, 17 dorsals, 6 sacrals, and 45+ caudals; I. bernissartensis: 11 cervicals, 17 dorsals, 7 sacrals, and 50+ caudals; Ouranosaurus nigeriensis: 11 cervicals, ~17 dorsals, 6 sacrals, and 40+ caudals.

The atlas (fig. 19.12) comprises a crescentic intercentrum bearing a concave dorsal margin that receives the odontoid process of the axis, a smoothly concave articulation for the occipital condyle and liplike facets for attachment of the single-headed first cervical rib (fig. 19.12). The neural arch is paired, and each half has a small articular surface for the occipital condyle, above which is a narrow arch that curves over the neural canal. From the dorsolateral margin of the arch, there is a slender transverse process that is directed obliquely backward and upward; medially, the postzygapophysis is horizontal. The ventral portion of the neural arch curves forward and supports the small proatlas elements interposed between the occiput and the atlas. Proatlases are rarely found, but have been described in Iguanodon bernissartensis (Norman 1980) and Ouranosaurus nigeriensis (Taquet 1976). As in all archosaurs, the atlas pleurocentrum is attached to the centrum of the axis, forming the rotational axis for the atlas-axis complex. The axis is notable for a prominent neural spine that forms a bladelike structure above the centrum, extending forward between the separate arches of the atlas. In addition, the ventral surface of the axis pleurocentrum has a small wedge-shaped intercentrum attached along its rostroventral border. Both of these structures control the movement between the atlas and the axis. A large parapophyseal facet is present immediately behind the rostral articular surface of the centrum, and above and caudal to this, there is a small diapophyseal facet. The caudal surface of the centrum is concave, the degree of concavity depending on the species and size of the individual. This surface receives the convex cranial articular surface of the third cervical.

The form of the third cervical is like that of the remainder of the cervical series. The main body of the centrum has a large convex articular surface (least developed in Tenontosaurus, Dryosaurus, and Camptosaurus dispar), behind which the centrum is contracted laterally, but retains a prominent ventral keel; caudally, the articular surface is concave. The neural arch is divided into oblique forwardly directed processes that support the prezygapophyses. Caudally the postzygapophyses are supported by long, arched processes that diverge from a low midline ridge or spine.

A number of serial changes occur down the cervical series. The neural spine becomes gradually more prominent. The centra become narrower and taller. The zygapophyses recede into the larger and broader neural platform that develops to support the neural spine. The parapophysis for the rib head becomes larger and begins to migrate dorsally to lie on or close to the neurocentral suture.

Ribs are found on all cervicals. The first is a simple rod, the remainder are bicephalous and increase in length as the dorsal series is approached. Ouranosaurus is unusual in having cervical ribs that are randomly fused to their vertebrae (Taquet 1976).

The change from cervical to dorsal is marked for convenience by the migration of the parapophysis from the neurocentral suture onto the base of the neural arch. Cranial dorsals retain many cervical features, so the overall transition is not abrupt. Farther along the dorsal series the centra become narrower and taller, while the articular surfaces become uniformly amphiplatyan, although in some taxa the dorsals closer to the sacrum develop mild opisthocoely. The neural arch develops a broad horizontal platform to support the elevated, generally obliquely rectangular, neural spine, while laterally the diapophyses develop into robust, oblique processes that support the tuberculum of the rib distally and the proximal portion becomes notched with a large, thumb-print-like depression, which is the facet for the capitulum of the rib. Down the dorsal series the parapophysis shows a characteristic migration first up the side of the neural arch to the neural platform and then outward along the diapophyseal process, eventually merging with the diapophysis either completely or in a distinctly stepped facet in the most caudal dorsals. Neural spines increase in height along the series as it approaches the sacrum in most taxa, excepting the smaller species (notably dryosaurids). The degree of lengthening of the neural spines reaches is greatest expression in Ouranosaurus nigeriensis (fig. 19.15; Taquet 1976), where the spine is as much as nine times the height of the centrum (fig. 19.16). The centra of the last dorsal vertebrae are axially compressed, have broad articular surfaces, are opisthocoelous, and have zygapophyses that are practically horizontal. The last neural spine in the dorsal series of Ouranosaurus is unusual in that it has a groove down the caudal margin; this evidently fit against the cranial margin of the spine of the first sacral vertebra (Taquet 1976). The entire dorsal series is gently arched, slightly more so closer to the cervical-dorsal junction.

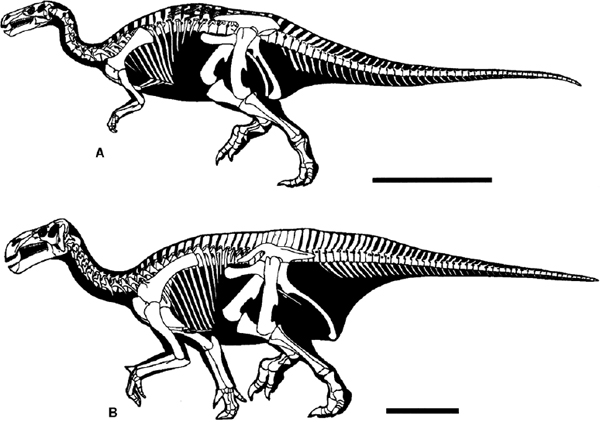

FIGURE 19.14. Skeletal reconstructions: A, Camptosaurus dispar; B, Iguanodon bernissartensis. Scale = 1 m. (Courtesy of and copyright by G. S. Paul.)

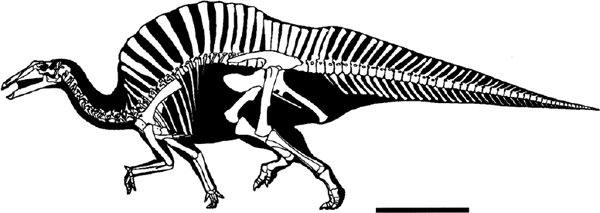

FIGURE 19.15. Skeletal reconstruction: Ouranosaurus nigeriensis. Scale = 1 m. (Courtesy of G. S. Paul; amended by removal of nuchal membrane.)

FIGURE 19.16. Dorsal vertebrae: A, Iguanodon bernissartensis; B, Iguanodon atherfieldensis; C, Ouranosaurus nigeriensis. Scale = 5 cm. (A from Norman 1980; B from Norman 1986; C from Taquet 1976.)

The dorsal vertebrae (and caudals) of Iguanodon fittoni are distinctive in their long, narrow, and steeply inclined neural spines (Norman 1987b). These do not in any way resemble those of Ouranosaurus nigeriensis. Another more robust contemporary species, Iguanodon dawsoni, has larger vertebrae with shorter, broader neural spines and almost cuboid caudal centra—these are most similar to those referred to as Camptosaurus browni (Gilmore 1909). The composite reconstruction of a dorsal vertebra of Muttaburrasaurus langdoni resembles in its proportions that of I. dawsoni or a large camptosaur (Bartholomai and Molnar 1981).

In Iguanodon spp. (fig. 19.14) cranial dorsal ribs differ little from those of the cervical region. However, they increase in length markedly at the front of the dorsal series; the fifth and sixth ribs are the longest. Ribs 3 through 9 develop blunt distal ends that mark the articulation with the sternal ribs. Farther along the series, the rib shafts become narrower and shorter as they approach the sacrum. The principal load-bearing sacral ribs and vertebrae are found at the cranial end of the sacrum. The sacral ribs are massive, twisted elements forming a sacral yoke laterally where their distal ends meet, fuse together, and have an extensive articulation with adjacent centra and neural arches. The neural arches of adjacent vertebrae are often fused together, as are the neural spines. The peg-and-socket articulation between sacral centra is known in both Camptosaurus and species of Iguanodon and may be a general adaptation associated with strengthening the sacrocentral articulation, particularly in immature individuals.

Proximal caudals have tall, rectangular centra, with well-developed ribs fused to the vertebra along the line of the neurocentral contact. Neural spines are tall and obliquely inclined distally. They are also narrower than the neural spines of the dorsal vertebrae. The prezygapophyses are small and point obliquely forward, while the postzygapophyses are small and located on the distal margin of the neural spine. Middle caudals have lost the caudal ribs and hence are hexagonal or octagonal in cross section. Centrum height is reduced. The centra of the distal caudals are cylindrical and yet again reduced in height. They bear separate chevron facets on the ventral margin of the distal articular surface. The neural spines become reduced to apophyses for the support of the postzygapophyses.

Chevrons are not reported consistently, but are found first between the second and third caudal vertebrae and are long, slender, and slightly curved laterally compressed rods. There is a well-developed hemal canal at the proximal end, above which is an expanded bifaceted articulation with both distal and proximal undersurfaces of adjoining vertebrae. Chevrons regularly shorten along the caudal series, mirroring the decline in height of the neural spines dorsally, and disappear toward the middle of the distal caudal series.

APPENDICULAR SKELETON

In Tenontosaurus the scapula is longer than the humerus and within iguanodontians these proportions are constant, although in some forms (Dryosaurus) the scapula and humerus are approximately equal in length. The scapula has an essentially straight blade that flares distally along its caudal edge; there is no forward-projecting acromion process. A similar condition is seen in Zalmoxes. In contrast, the scapula of Dryosaurus and all of the more derived nonhadrosaurid iguanodontians is flared distally and proximally bears a forwardly projecting acromion.

The coracoid in all iguanodontians is a large, dish-shaped element with a prominent foramen that is most often clearly separated from the scapulocoracoid suture, although in some examples (Iguanodon bernissartensis, Camptosaurus dispar) the foramen appears as a notch on the scapulocoracoid suture. The latter is thick and undulates along its length; in one example (Ouranosaurus), the scapula and coracoid are fused together, which may be either an aberrant pathology or an autapomorphy. There is a prominent, hooked sternal process on the caudal margin of the coracoid, and in more derived forms the external surface of the coracoid is marked by a prominent diagonal ridge (Altirhinus, Probactrosaurus).

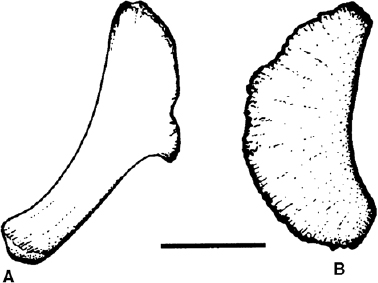

The sternal bone is variable in iguanodontians (fig. 19.17). In basal forms (Tenontosaurus, Dryosaurus, Camptosaurus) this bone is large, flat, and reniform (Dodson 1980; Galton 1981b; Erickson 1988; Forster 1990a). In all more derived taxa the sternal has a hatchetlike shape, the blade formed by the portions of the sternals that face each other across the midline of the thorax, while caudolaterally there is a rod-shaped extension; this condition is found consistently in Lurdusaurus arenatus (Chabli 1988) and all more derived iguanodontians.

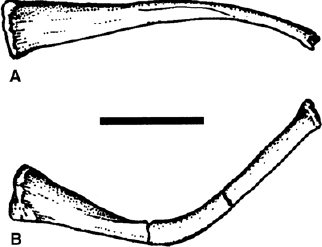

The humerus of Tenontosaurus and Zalmoxes is robust and has a prominent and angular deltopectoral crest that extends for approximately 50% of the length of the humeral shaft; this general morphology is reminiscent of that seen in Hypsilophodon and basal euornithopods and is a trait that recurs in hadrosaurids. The humerus of Dryosaurus (Janensch 1955) and the majority of more derived iguanodontians is far more gently sigmoid with the deltopectoral crest far less prominent, but thickened.

The forearm bones of Tenontosaurus (Forster 1990a) are notably bowed, and the ulna lacks an olecranon process—a feature seen in basal euornithopods. The forearm of Zalmoxes is similarly bowed, but the ulna has a more prominent olecranon. In Dryosaurus (Janensch 1955) the forearm bones are shorter, more slender, and straighter than in the more basal forms. The radius and ulna are straight and more robust in Camptosaurus, a feature that is likely correlated with the structure and function of the carpus and manus in this taxon. All more derived iguanodontians exhibit robust and straight forearm bones, except Probactrosaurus, which has an elongate, slender, and curved radius and ulna. Special note should be made of Lurdusaurus, because among iguanodontians it exhibits an extraordinary degree of robustness in its entire forelimb (Taquet and Russell 1999).

FIGURE 19.17. Sternals: A, Iguanodon atherfieldensis; B, Camptosaurus dispar. Scale = 5 cm. (From Norman 1986; B from Dodson and Madsen 1981.)

FIGURE 19.18. Manus of Iguanodon bernissartensis in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm. (From Norman 1980.)

The carpus in Tenontosaurus reportedly consists of three proximal elements (radiale, intermedium, and ulnare) of which the stout radiale is the largest; several sesamoid-like distal carpals are also present (Forster 1990a). Nothing is known at present of the carpus of Zalmoxes. The dryosaurid carpus was clearly ossified, but is poorly known (Galton 1981b). The carpus and manus of Camptosaurus are well preserved (Gilmore 1909) and show the development of a heavily co-ossified blocklike carpus that incorporates metacarpal 1 (as a short, diagonally oriented block), a radiale, an intermedium, and an ulnare, along with some distal carpals (Gilmore 1909; Erickson 1988). The carpals of Iguanodon spp. (Norman 1980, 1986), Ouranosaurus (Taquet 1976), and Lurdusaurus (Taquet and Russell 1999) are all unusually heavily ossified and show a similar general form to that seen in Camptosaurus. In all these instances the distal carpals were fused immovably to the rest of the carpal block. In some extreme examples carpal ligaments are found ossified on the surface of the carpals (Norman 1980). More derived iguanodontians have less well-preserved evidence of carpal structure. Altirhinus (Norman 1988) has individually preserved carpal bones, but it is uncertain whether these formed a fused block during later stages of ontogeny; the fact that the manus of this taxon possessed a large conical pollex ungual and shows evidence of weight-supporting adaptations is certainly suggestive of a well-ossified carpus. Eolambia possessed a conical pollex ungual and short, flattened manus unguals, but its carpal structure is unknown. Probactrosaurus possessed a small, conical pollex ungual (Norman 2002) and shows evidence of manus weight-supporting characteristics, but at present its carpal structure is entirely unknown.

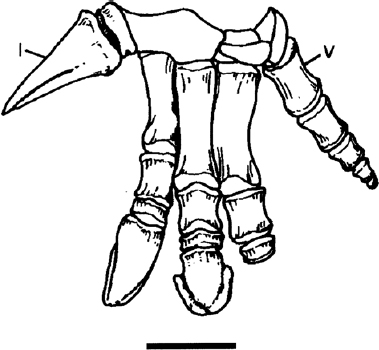

The metacarpals of Tenontosaurus have flattened proximal ends, are generally dumbell-shaped, and are arrayed in a spreading manner (Forster 1990a). The manus is not well known in either Zalmoxes or Dryosaurus. Camptosaurus and Lurdusaurus possess short, dumbell-like metacarpals II–V (the first metacarpal being short and fused obliquely to the carpal block). In contrast all more derived iguanodontians where the manus is reasonably well-preserved exhibit metacarpals II–IV that are narrow, elongate, and closely appressed; metacarpal V is uniformly shorter and more dumbell-shaped, and in many instances can be shown to diverge strongly from the median axis of the manus (fig. 19.18; Norman 1980, 1986).

The manus of Tenontosaurus has a phalangeal formula of 2-3-3-1(?2)-1(?2) (Dodson 1980; Forster 1990a). Manus digits I–III and possibly IV bore pointed, claw-shaped unguals, and all digits in all iguanodontians are capable of hyperextension to some degree (Norman 1980). Camptosaurus had similarly shaped unguals, except for digit I, which has a subconical shape (Erickson 1988). In Camptosaurus the digital formula is 2-3-3-3-2 (Gilmore 1909; Erickson 1988). Iguanodon exhibits the classically conical ungual on digit I and also has dorsoventrally flattened and distally blunt unguals II and III, with ungual II being more elongate and medially twisted. Iguanodon bernissartensis, which exhibits a well-preserved articulated manus, has the digital formula of 2-3-3-2-4, indicating unexpected hyperphalangy of digit V (given the almost universal trend for lateral digit reduction seen in Dinosauria). More derived iguanodontians (perhaps even I. atherfieldensis) may lack the first phalanx of digit I, but since this bone is a thin disc in I. bernissartensis, it may readily become fused to the ungual or lost if manus elements are disarticulated.

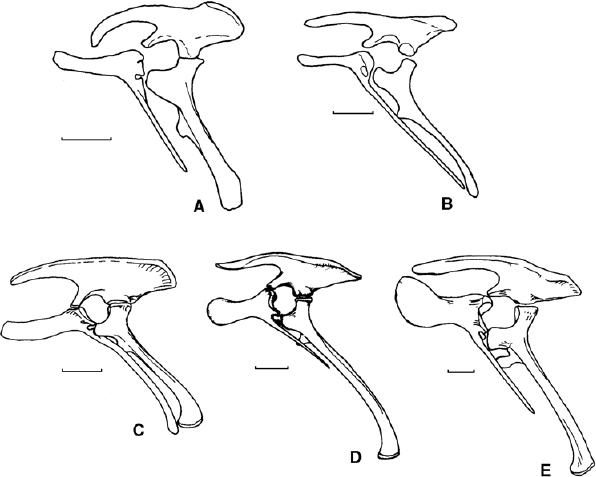

The ilium of iguanodontians is variable in form (fig. 19.20). In Tenontosaurus it is strongly laterally compressed and has a long, distinctly arched preacetabular process and a horizontal mid-section, while the postacetabular process has an upturned and thickened dorsal edge; the brevis shelf is narrow (Forster 1990a). The ilium of Zalmoxes is distinctive; it has a dorsoventrally compressed, robust preacetabular process, a long, arched dorsal margin, and a slightly transversely expanded dorsal margin in the region just caudal to the ischial peduncle; the postacetabular process is deep and there is no brevis shelf. The ilium of Dryosaurus has a distinctive low profile, especially caudally, and a wide brevis shelf (fig. 19.19). Planicoxa venenica (DiCroce and Carpenter 2001) has a long preacetabular process, the postacetabular process is dorsoventrally compressed and flared strongly laterally, and it has a well-developed brevis shelf. Camptosaurus has an ilium with a higher lateral profile and a similarly long, straight preacetabular process, a deeper postacetabular process, and a moderately developed brevis shelf. In Iguanodon and more derived iguanodontians, the ilium has a long preacetabular process, which is often deflected ventrally; dorsally the blade of the ilium is more or less straight and the upper portion of the postacetabular process is thickened and everted, but does not show the notch and pendent lip characteristic of hadrosaurid iguanodontians. The postacetabular process is triangular, and its ventral edge is usually inflected medially to form a brevis shelf of varying proportions. The pubic peduncle of the ilium is triangular in cross section, with a prominent lateral margin that forms a remnant of the more extensive supraacetabular flange seen in other dinosaurs. The ischial peduncle is a broad, generally bulbous area at the back of the acetabulum; its surface, if well preserved, is flattened rostrolaterally, and this may be associated with femoral motion.

FIGURE 19.19. Pelvis in left lateral view: A, Tenontosaurus tilletti; B, Dryosaurus altus; C, Camptosaurus dispar; D, Iguanodon atherfieldensis; E, Ouranosaurus nigeriensis. Scale = 10 cm. (A from Coria and Salgado 1996b; B from Galton 1981b; C–E from Norman and Weishampel 1990.)

The pubis also varies considerably in shape and proportions among iguanodontians. More basal forms (apart from Tenontosaurus) have a pubis that is similar to that seen in basal euornithopods. In Tenontosaurus the prepubic process is blade-shaped, being transversely flattened but variable in shape, tending to be upturned and tapering slightly toward its distal end (Forster 1990a). The shaft of the pubis is considerably shorter than the ischium and tapers to a sharp point that lies along the ischial shaft. In contrast the pubis of Zalmoxes has a narrow, rod-shaped prepubic process, even though the extent of the process is unknown (the prepubic process of Rhabdodon cf. priscus [Pincemaille 1997, 2002] has the form of a narrow, laterally compressed blade). In dryosaurids, the prepubic process is narrow, but flattened laterally (and in some instances dorsoventrally, Galton 1981b) and, in contrast to Tenontosaurus, the caudal process is long and slender, terminating at a pubic symphysis alongside the distal end of the ischial shaft when the two bones are articulated; this latter condition is more reminiscent of the morphology of basal euornithopods. Camptosaurus has a deeper prepubic process, but retains the long pubic shaft that terminates alongside the distal end of the ischium. In all more derived iguanodontians the prepubic process is deep and expanded distally to varying degrees, while the pubic shaft is short and tapering, terminating near midshaft of the ischium and lacking entirely a symphysis.

The shaft of the ischium in Tenontosaurus is a straight, laterally flattened shaft with a distinctive distal expansion, which is a lateral bulge, rather than a craniocaudal expansion that forms a distinctive boot, as seen in more derived iguanodontians. The obturator process is large, tablike, and positioned more than one-third of the way down the shaft, rather than close to the proximal end. The ischium of Zalmoxes is unique among euornithopods in lacking an obturator process; the shaft is ventrally curved and is unexpanded at its distal end. The ischium of all more derived iguanodontians is moderately uniform in shape. The shaft is generally curved (arched ventrally), has a obturator process located within the proximal quarter of the ischial shaft, and its distal end is developed into a distinct boot of varying size. This trait might be variable within more derived iguanodontians; the imperfectly preserved ischium of Altirhinus is neither arched nor does it show any indication of supporting a boot.

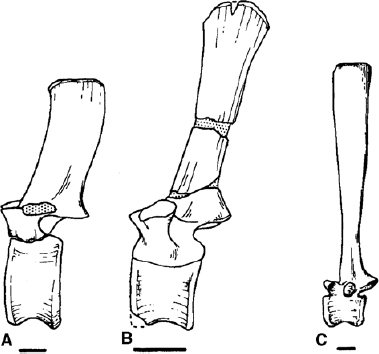

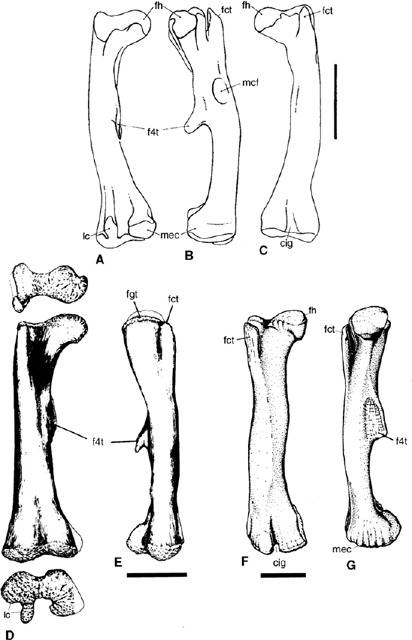

The femur of Tenontosaurus (fig. 19.20) is robust, nearly straight (Forster 1990a), and displays a pendent fourth trochanter. In addition, it has a broad and shallow cranial extensor groove on its distal articular end. The femur of Zalmoxes, although robust with a shallow extensor groove, has a straight shaft in lateral view, but is decidedly bowed medially. The fourth trochanter is broken off at its base. In contrast, the femora of Dryosaurus (fig. 19.20) and Valdosaurus (Galton 1975; Galton and Taquet 1982) are bowed, gracile in build when compared to the two previous examples, and have a distinct extensor groove separating the distal femoral condyles (which is particularly well developed in the latter genus). The fourth trochanter is pendent and proximally positioned on the shaft, and there is a distinct pit (possibly for insertion of a part of the caudofemoral musculature) adjacent to the base of the fourth trochanter. This muscle scar is commonly observed in small, cursorial euornithopods. Camptosaurus and more derived iguanodontians (fig. 19.20) have larger and more robust femora. In these examples the femoral shaft is curved distally and the fourth trochanter is deeper, positioned on midshaft, and more blade-shaped with a slightly pendent tip, or it has a triangular profile. The extensor groove becomes deeper and more tubular in shape, becoming partially enclosed by expansion of small lips from the edges of the adjacent condyles. In hadrosaurids this groove becomes completely enclosed by bone to form a distinct tunnel running between the articular surface and the dorsal surface of the femoral shaft.

FIGURE 19.20. Femur: A–C, Dryosaurus lettowvorbecki; D, E, Tenontosaurus tilletti; F, G, Iguanodon atherfieldensis. Scale = 10 cm. (A–C from Sues and Norman 1990; D, E from Forster 1990a; F, G from Norman 1977.)

In Tenontosaurus the tibia in juveniles is slightly but consistently longer than the femur, but in larger individuals it becomes shorter than the femur (Dodson 1980; Forster 1990a). The tibia is consistently longer than the femur in dryosaurids (Galton 1981b) and more similar in its proportions to many basal euornithopods. In Camptosaurus and all more derived iguanodontians the tibia is always shorter than the femur.

The proximal tarsals cap the ends of the tibia and fibula and are often preserved, which is not so often the case with the smaller and disc-shaped distal tarsal series. The astragalus of Tenontosaurus is unusual in that it lacks an ascending process (Forster 1990a). Most iguanodontians possess a well-developed ascending process on the astragalus and a corresponding facet on the cranial surface of the distal end of the tibia. In Tenontosaurus the tarsus comprises two distal tarsals attached to metatarsals III and IV. The number of distal tarsals preserved in more derived iguanodontians varies with preservational conditions.

The pes in iguanodontians shows a consistent trend toward reduction of the lateral digits. In Tenontosaurus metatarsal V is reduced to a short splint as in basal euornithopods. Metatarsals I–IV are well developed and mutually appressed proximally. The pes has a phalangeal formula of 2-3-4-5-0 (Forster 1990a) and the unguals are narrow and pointed, which is slightly unexpected in such a large animal. The pes of Dryosaurus retains a vestigial metatarsal I and lacks metatarsal V. The phalangeal formula is 0-3-4-5-0, indicating an autapomorphic loss of the entirety of digit I. In contrast the pes of Camptosaurus is notable for the retention of two phalanges on digit I, and the unguals, although dorsoventrally compressed, are pointed as in Tenontosaurus and Dryosaurus. The pes has three functional toes (digits II–IV). Among more derived iguanodontians the digital formula of the pes does not vary significantly (Iguanodon atherfieldensis, 0-3-4-5-0; I. bernissartensis, 0-3-4-5-0; Ouranosaurus nigeriensis, 0-3-4-5-0). In Iguanodon, the first digit is represented by a splint-like metatarsal alone; whether this bone is likely to have been preserved in other taxa is uncertain—presence or absence may well reflect preservational bias. The pedal unguals in all these forms are dorsoventrally flattened, blunt ended, and hooflike (but they are narrow and retain the prominent lateral claw grooves); these unguals are never as short and broadly rounded as is the case in the majority of hadrosaurids.

Systematics and Evolution

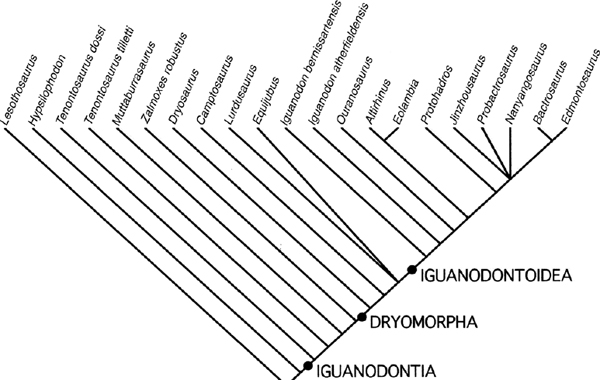

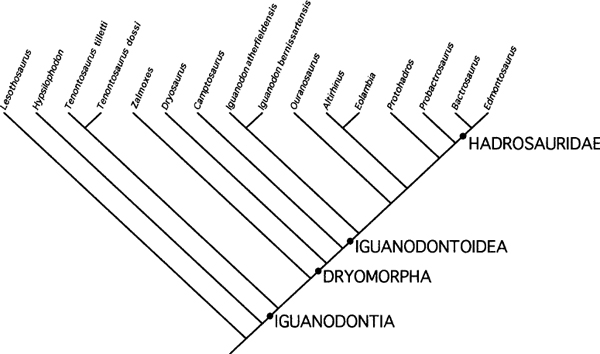

In recent years the discovery of many new taxa and the redescription of older known forms have prompted a variety of new systematic analyses involving various combinations of iguanodontians (Godefroit et al. 1998b; Head 1998, 2001; Kirkland 1998b; Norman 1990b, 1998; Xu et al. 2000b). A new data matrix based on 21 taxa and 67 characters was generated during the formulation of this chapter. Lesothosaurus (Thulborn 1970a, 1972; Sereno 1991b) and Hypsilophodon (Galton 1974a) were used as outgroups. This new analysis forms the basis of the discussion of the phylogeny below. The analysis indicates a consistent, strongly pectinate scheme of taxa that form a stem lineage culminating in Hadrosauridae (see chapter 20).

A special note should be made concerning Gasparinisaura, Zalmoxes, and Rhabdodon. The first has been described as a basal iguanodontian (Coria and Salgado 1996b; Salgado et al. 1997c), but further analysis has resulted in its placement among more basal euornithopods (chapter 18). G. cincosaltensis was included in the matrix above; rerunning the data revealed a consistent topology in which Gasparinisaura is basal to Tenontosaurus. On the other hand, the position of Zalmoxes and Rhabodon in this chapter, as members of Iguanodontia, differs from that suggested by Weishampel et al. (2003), where together they are considered the sister taxon to Iguanodontia.

The full data set was run with the characters unordered and unweighted, using the branch-and-bound option under PAUP*4.0b10 (Swofford 1999). The first run generated 315 equally parsimonious trees with a considerable degree of consensus, as revealed by the strict consensus and 50% majority rule consensus trees. The characters were reweighted using the maximum value of the rescaled consistency indexes in order to emphasize the characters that were providing the greatest parsimony signal and reduce the effect of those that generate analytic noise or (potentially) homoplasy. This second run generated 15 equally parsimonious trees with a similar topology. The strict consensus tree generated by this run is presented in figure 19.21) and is almost identical in its topology to the 50% majority rule consensus tree. Tree statistics: L = 78.7 steps (min 64.6, max 206.7), CI = 0.82, RI = 0.90, RC = 0.74. These results highlight a lack of resolution involving Lurdusaurus and Equijubus in the middle of the tree, and a broader polytomy among Probactrosaurus, Jinzhousaurus, Nanyangosaurus, and Hadrosauridae. Reanalysis of these data proceeded via serial deletion of taxa. Several taxa (Muttaburrasaurus, Lurdusaurus, Equijubus, Nanyangosaurus, and Jinzhousaurus) were responsible for much of the instability, and it is not surprising that this is the case given the absence of data in all five taxa. These five taxa were deleted from the analysis and the data rerun. This produced two equally parsimonious trees that differed only in the positioning of Iguanodon atherfieldensis and I. bernissartensis (either as serially derived on the tree or as sister taxa). Using the same procedure of reweighting and reanalysis generated a single most parsimonious tree (fig. 19.22). Basic tree statistics: L = 72.1 steps (min 62.1, max 186.7); CI = 0.86; RI = 0.92; RC = 0.79.

Tenontosaurus is consistently positioned as the most basal member of Iguanodontia confirming its placement by Forster (1990a) and Weishampel and Heinrich (1992). Tenontosaurus tilletti is a medium-sized (length approximately 7 m) ornithopod from the Aptian of the Cloverly Formation, Montana and Wyoming, United States. Originally described and classified as a member of Iguanodontidae (Ostrom 1970a), it has had a checkered systematic history. It was referred to Hypsilophodontidae by Dodson (1980) and Norman (1984a, 1990b, 1998) and considered to be a taxon that was anatomically convergent with later iguanodontids. Sereno (1984, 1986) placed it as the most basal member of Iguanodontia. The postcranial skeleton was described by Forster (1990a) and its systematic position was reassessed, confirming the views of Sereno. More recent systematic analyses on basal euornithopods (Weishampel and Heinrich 1992; Coria and Salgado 1996b; Salgado et al. 1997c; Winkler et al. 1997b) further reinforced this view.

Tenontosaurus tilletti and T. dossi (from the Aptian of Texas, southern United States, Winkler et al. 1997b), are well supported as sister taxa, based on an enlarged external naris, a dentary ramus with parallel dorsal and ventral margins, elevated caudal dorsal neural spines, and loss of a phalanx from digit III of the manus. T. dossi, although anatomically similar to T. tilletti, is unusual in retaining a more basal euornithopod feature by having at least one premaxillary tooth.

Muttaburrsaurus langdoni, from the Aptian–Albian of Queensland, Australia (Bartholomai and Molnar 1981), is the next most derived taxon in this analysis, but until its anatomy is better known its position will remain a little uncertain; some aspects of its known cranial (form of maxillary tooth crowns) and postcranial anatomy (laterally compressed and bladelike prepubic process, shallow extensor groove on the distal end of the femur) place it close to both Tenontosaurus and the next most derived taxon, Zalmoxes robustus.

FIGURE 19.21. Strict consensus tree from 15 equally parsimonious trees generated with character states unordered and of equal weight, followed by a rerun using the reweighting option in PAUP*4.0b10.

FIGURE 19.22. Single most parsimonious tree generated following deletion of five taxa. Character states were first run unordered and with equal weight; this generated two equally parsimonious trees. Reweighting and rerunning this analysis following deletion of five taxa generated the single most parsimonious tree shown here.

The next clade includes Zalmoxes robustus from the Maastrichtian of Romania (Nopcsa 1902; Weishampel et al. 2003); this clade also includes Rhabdodon priscus from the Campanian of France (Matheron 1869) and Mochlodon suessi Seeley, 1881, from the Gosau Formation (Campanian) of Austria (Seeley 1881). R. priscus is likely to be better known through the recent discovery of a partial, associated skeleton (Pincemaille 1997, 2002); R. priscus differs notably from Z. robustus in possessing an ischium with an obturator process (the absence of an obturator process is an autapomorphy of Z. robustus). The clade is recognized by the development of a bifurcated ventral process on the predentary, a thickened lateral flange on the dorsal margin of the ilium, a rounded (rather than a flattened) cross section of the ischial shaft, and an arched (rather than straight) ischium.

The next clade constitutes Dryomorpha and includes Dryosaurus altus, D. lettowvorbecki from the Kimmeridgian of the western United States and Tanzania, southern Africa, Valdosaurus canaliculatus from the Barremian of Europe (Marsh 1878b; Pompeckj 1920; Galton 1975), and all more derived Iguanodontians (Sereno 1986). This clade is distinguished by the elongation of the lateral process of the premaxilla so that it contacts the lacrimal-prefrontal, the development of a distinct primary ridge on the maxillary crowns, the enclosure of the paraquadrate foramen between the quadratojugal and quadrate embayment, the development of a forwardly projecting acromial process on the scapula, an obturator process that is positioned near to the acetabular margin (rather than nearer midshaft), a booted distal tip to the ischium, and a distinctive extensor (cranial intercondylar) groove on the distal end of the femur. Dryosaurids (Dryosaurus and Valdosaurus) are lightly built cursors that, in their body proportions and pubis structure, resemble the more traditional basal euornithopods such as Hypsilophodon (Galton 1974a) to a greater extent than they do the larger and more robust, but more basal, iguanodontians listed above. Dryosaurids exhibit unusually specialized and narrow feet, having lost the entirety of digit I, a feature that is associated with more derived iguanodontians.

The clade that includes Camptosaurus dispar from the Kimmeridgian–Berriasian of North America (Marsh 1879c) and all more derived forms is well supported and has been named Ankylopollexia (Sereno 1986). These forms are unified by their possession of a specially modified manus and forelimb to accommodate a spinelike pollex ungual. These animals also have a more elongate preorbital region and a generally lower skull profile; the frontal participates less in the orbital margin than in dryomorphans; and camptosaurs show an autapomorphy in that the paraquadrate foramen has been completely occluded by quadratojugal—a feature that appears later in Hadrosauridae and some iguanodontians close to Hadrosauridae (Protohadros).

The clade immediately in succession to Camptosaurus (Styracosterna: Probactrosaurus and all more derived iguanodontians) is not supported in this analysis. Lurdusaurus arenatus, from the Aptian of Niger (Taquet and Russell 1999), is the next most derived iguanodontian and is based on a partial skeleton that has only been briefly described to date. Styracosterna (amended) comprises Lurdusaurus and all more derived iguanodontians and is defined by the possession of hatchet-shaped sternal bones and flattened manus unguals, as well as by the structure of the pelvis. Lurdusaurus is exceptionally robust and retains the conical pollex and well-ossified carpus, as well as the broad, short, spreading manus seen in Camptosaurus, rather than the narrower, bundled, and more elongate metacarpals II–IV seen in more derived taxa.

Equijubus normani, known from an articulated skull and several cervical vertebrae, is from the Aptian–Albian of Gansu Province, China (You et al. 2003b). Preliminary analysis places this taxon between Lurdusaurus and Iguanodon within the revised styracosternan clade.

The clade named both Iguanodontoidea and Hadrosauriformes includes species of Iguanodon and all more derived iguanodontians (Sereno 1986, and Sereno 1997, 1998, 1999a, respectively). It is diagnosed by the strong offset of the premaxilla margin relative to the maxilla, the peg-in-socket style articulation between the maxilla and the jugal, the development of a pronounced diastema between the beak and the mesial dentition, mammillations on the marginal denticles of the teeth, maxillary crowns that are narrower and more lanceolate than the dentary crowns, closely appressed metacarpals II–IV, a deep, laterally flattened prepubic process, a triangular fourth trochanter, a deep, almost tubular extensor (cranial intercondylar) groove, and blunt pedal ungual phalanges. Earlier assessment of the taxa that range between Camptosaurus and Hadrosauridae formed the basis for a singular taxonomic hierarchy named Iguanodontoidea by Sereno (1986), which was later amended to Hadrosauriformes without explanation (Sereno 1997, 1998, 1999a). Further systematic analysis (Head 1998, 2001; Kirkland 1998b; Xu et al. 2000b, and that conducted here) suggests that the original topology is not supported and that the clade names and their component taxa have to be revised. Retention of Iguanodontoidea in its amended form is preferred in order to minimize the confusion caused by the proliferation of clade names.

It has been claimed that Ouranosaurus nigeriensis from the Aptian of Niger (Taquet 1975) is the sister taxon to Hadrosauridae (Sereno 1984, 1986, 1990a, 1997, 1998, 1999a), recognized hierarchically as Hadrosauroidea (Sereno 1986). This topology has been questioned on a number of occasions (Norman 1990b, 1998, 2002; Head 1998, 2001; Kirkland 1998b; Xu et al. 2000b). The present analysis also places Ouranosaurus close to Iguanodon spp. on the iguanodontian stem lineage and basal to a number of more derived nonhadrosaurid iguanodontians (Probactrosaurus, Eolambia, Protohadros, Altirhinus). Characters such as the narrowing of the skull table, the reflection of the rim of the premaxilla, an enlarged diastema, elongation of the dorsal neural spines, and extreme dilation of the prepubic process are variously homo-plastic within Iguanodontia or autapomorphies of Ouranosaurus.

Altirhinus kurzanovi, from the Barremian–Aptian of southern Mongolia (Norman 1998), and Eolambia caroljonesa from the Albian of Utah, western United States (Kirkland 1998b), form sister taxa in a small clade that is basal to the successively more derived Protohadros, Probactrosaurus, and Hadrosauridae. Altirhinus, although far from completely described, is known from several partial skeletons and skulls; Eolambia is also described on the basis of fragmentary dissociated remains. However this latter taxon may soon be known from additional material (Maxwell, pers. comm.), so the topology of this minor clade may well change. At present it is recognized by the suspected closure of the external antorbital fenestra, the more lateral and elevated position of the coronoid process, and tooth replacement patterns.

Protohadros byrdi, from the Cenomanian of Texas, southern United States (Head 1998), is currently known only from a disarticulated skull and is placed closer to Hadrosauridae, as proposed by Head (2001) on the basis of the closure of the paraquadrate foramen, the parallel-sided form of the grooves for replacement teeth in the alveolar trough, and the broadening of the occlusal surface. Protohadros is itself a specialized taxon with an unusually enlarged and ventrally deflected muzzle.

Probactrosaurus gobiensis, from the Barremian–Albian (Itterbeeck et al. 2001) of Inner Mongolia, China (Rozhdestvensky 1966) appears in this analysis and that of Norman (2002) as the sister taxon to Hadrosauridae (fig. 19.22). Probactrosaurus shares this position in a polytomy with Jinzhousaurus yangi (Early Cretaceous, Yixian Formation, Liaoning Province, China; Wang and Xu 2001a, 2001b), Nanyangosaurus zhugeii (Early Cretaceous, Sangping Formation, Henan Province, China, Xu et al. 2000b), and Hadrosauridae in the analysis undertaken in which all taxa are considered (fig. 19.21). At present any attempt to redefine a clade named Hadrosauroidea as a clade comprising Hadrosauridae and its basal sister taxon (previously Ouranosaurus + Hadrosauridae) is being avoided given the present incomplete knowledge of various taxa close to this position on the cladogram.

Additional taxa, such as Draconyx loureiroi, from the Tithonian of Portugal (Mateus and Antunes 2001), and Planicoxa venenica, from the Barremian–Aptian of Utah, western United States (DiCroce and Carpenter 2001), were not included in this general review. Both are recently described fragmentary ornithopods that are nonhadrosaurid iguanodontian grade in morphology.

Biogeography

The earliest record of iguanodontians comprises indeterminate material (Callovosaurus leedsi) from the Callovian of England, while the earliest diagnosable form is Camptosaurus prestwichii from the early Kimmeridgian of England. Other remains include isolated femora from the Kimmeridgian–Tithonian of Portugal (Galton 1980d); the well-preserved Camptosaurus dispar from the Kimmeridgian of the United States; and Dryosaurus, known from the Kimmeridgian of North America and Africa. The latest-known taxon is Zalmoxes robustus from the Maastrichtian of Europe. Given the basal position of Tenontosaurus (Aptian of the United States) within Iguanodontia, a substantial ghost lineage duration is implied at the origin of the clade.

These animals had an African–European–North American distribution by the Upper Jurassic (Milner and Norman 1984). By the Early Cretaceous iguanodontians had achieved a virtually cosmopolitan distribution, ranging across Euramerica, Asia, Africa, and Australia (with reports of potential nonhadrosaurid Cretaceous iguanodontians in South America [Coria 1999]). The early Late Cretaceous (Albian–Cenomanian) records a significant pan-Laurasian distribution of taxa (Head and Kobayashi 2001). The precise nature and timing of dispersal between Laurasian continental areas in mid-Cretaceous times cannot be accurately resolved. Modeling stratigraphic occurrence against area cladograms and taxonomic cladograms in the Mesozoic reveals that a cladistic-vicariance signal is significant during the mid-Jurassic to mid-Cretaceous interval and underscores the importance of continental-level vicariance in response to continental fragmentation. However, the signal is weak during the Late Cretaceous and may well be overwhelmed by dispersal and regional extinction (Upchurch et al. 2002). During the latter half of the Late Cretaceous nonhadrosaurid iguanodontians became restricted in their distribution, and were found only in Europe (the isolated tooth of Craspedodon lonzeensis may be tentatively assigned to Iguanodontia), where they are represented by unusually specialized and potentially relict taxa such as Rhabdodon priscus, Mochlodon suessi, and Zalmoxes robustus. In all other Laurasian and Gondwanan faunas basal iguanodontians were succeeded by hadrosaurid iguanodontians.

Paleobiology and Ecology