I assume that the summary of data in the last chapter has convinced you as strongly as it convinced me that there is more to survival and reincarnation data than quantum nonlocality can handle. We need more flesh on the backbone of the theory we have built, subtle though it may be.

Now if you consult the esoteric traditions about what this additional mechanism might be, the answer would be: this mechanism involves subtle bodies with individuality that we possess in addition to the physical body.14 These individual subtle bodies—a vital body connected with our particular life processes; a mental body connected with our individualized ways of mentation; and a supramental intellect body that contains the learned themes of movement of the mind, the vital, and the physical body—like the physical body, are bodies made of substances, the esoteric traditions declare, but the substances are more subtle, more refined, less quantifiable, and harder to control. You cannot say this thought weighs five ounces but only that this is a “heavy” thought. You can say that this thought was brief but not that it measured one inch. You try to be quiet when you meditate, but uninvited thoughts invade your mind regardless.

According to these traditions, when we die, we drop only the physical body; our subtle bodies survive. But what are these subtle bodies if not the products of the dualist notion of the individual soul? Are they not just another name for what we normally call the soul? And if we adopt the soul explanation of survival, however sophisticated its garb, aren't we going to fall into the difficulties of Cartesian dualism? That gives rise to troubling questions: What substance(s) mediates the interaction of these subtle bodies with the physical body? How is energy of the physical world conserved in the face of such interactions with these other bodies?

As I pondered the subtle bodies and the difficulties of interaction dualism, I explored the possibility of overcoming these difficulties with the new principles of our science within consciousness. It is not possible to postulate that the subtle bodies directly interact with the physical without digging a grave for the idea, agreed. On the other hand, if they don't interact with the physical, of what significance are they?

Well, there is another way of looking at the situation. Suppose that the subtle bodies neither interact with the physical nor with each other; suppose they run parallel, maintaining a correspondence with the physical. In other words, to every physical state, there is a corresponding supramental, mental, and vital state. Such a philosophy was formulated by the seventeenth-century physicist/philosopher Gottfried Leibniz to rescue mind-body dualism and is called psychophysical parallelism. The extension of the idea to include the supramental intellect and the vital body is straightforward; generalize the notion of the psyche, our internal world, to include the vital, the mental, and the intellect body. But psychophysical parallelism has never been popular because it is hard to see what maintains the correspondence, the smooth parallel movement of the disparate bodies. The question of interaction once again lurks behind the scene, doesn't it?

But wait, don't give up. The principles of our science within consciousness offer a solution. The problem of interaction is a tough one, no doubt, but suppose that the subtle substances of our subtle bodies are not Newtonian-determined “things,” but are quantum in nature. In other words, suppose we assume that the states of the vital, mental, and supramental bodies are probabilistic like those of the physical body. Suppose these states are states of quantum possibility within consciousness, not actuality, and consciousness collapses these possibilities into actuality.

Although the vital, mental, and supramental intellect bodies do not directly interact with the physical, that is, they move parallel to it, suppose consciousness recognizes parallel simultaneous states of the physical and of the vital-mental-intellect trio of the subtle body for its experience. From Jacobo Grinberg-Zylberbaum's experiments (see chapter 2), we already know that consciousness can and does synchronistically collapse similar states for nonlocally separated brains that are suitably correlated. And the collapse of a unique state of experience is one of recognition and choice, not one of exchange of energy, so all the problems of dualistic interaction are avoided.

So our science within consciousness allows us to postulate that we have other bodies besides the physical without the pitfalls of dualism. We do not need these bodies to interact with each other or with the physical. Instead, we say that consciousness mediates their interaction and maintains their parallelism. The next question is: What is the rationale for postulating such subtle bodies besides finding an explanation of the survival and reincarnation data? You cannot make arbitrary postulates to explain data; that is not science. Are there other profound reasons to suspect that we have a vital, a mental, and a supramental intellect body in addition to the physical?

The causal laws of physics are deterministic laws. Given initial conditions on position and velocity and the causal agents (forces) acting on the system, the laws of motion determine the future of all nonliving systems.

For example, suppose we want to know the whereabouts of the planet Jupiter some time in the future. Determine the position and velocity of the planet now. These “initial conditions,” plus the algorithms (logical step-by-step rules of instructions) generated by the knowledge of the nature of gravity and Newton's laws of motion, will enable any good computer to calculate the position of the planet for any future time. Even for quantum systems, statistical causal laws can predict the average behavior and evolution as long as we deal with a large enough number of objects or events (which is usually the case for submicroscopic systems). Nonliving systems are therefore cause-driven, and I call their behavior law-like.

But there is something peculiar about living systems. When we talk of the living, we not only deal with the movement of physical objects but also with feelings, feelings that need concepts such as survival, pleasure, pain, and so forth. These words are not in the vocabulary of the laws of physics; we never need such words to describe the nonliving. Molecules of the nonliving show no tendency to survive or to love. Nor do we need the concepts of pleasure and pain to describe molecular behavior. Instead, these concepts describe the contexts and meanings behind the contents or “feel” of living.

These “feels” are mapped or programmed in the physical body, and once programmed the physical body can carry out the function that the feeling is about. Thus, living organisms display “program-like” behavior giving away their secret—that they have another body that consists of the feels behind the programs that living organisms are capable of running (Goswami 1994). This is the vital body.

The biologist Rupert Sheldrake (1981) reaches the same conclusion by noting that the genes do not have the programs for morphogenesis or form-making. In Sheldrake's terminology, morphogenesis (development of the forms or organs that carry out biological functions) in living organisms is guided by nonlocal extra-physical morphogenetic fields. What is experienced as “feels” is operationally the morphogenetic fields; these are equivalent descriptions of the vital body.

Similarly, the biologist Roger Sperry, the philosopher John Searle, the mathematician Roger Penrose, and the artificial-intelligence researcher Ranan Banerji, all have pointed out that the brain which can be looked upon as a computer cannot process meaning that we so covet. Our lives center around meaning. Where does meaning come from? Computers process symbols, but the meaning of the symbols has to come from outside—the mind gives meaning to the symbols that the brain generates. You may ask why can't there be some other symbols for meaning, call them meaning symbols. But then we would need further symbols for the meaning of the meaning, ad infinitum (Sperry 1983; Searle 1992; Penrose 1989; Banerji 1994).

The feels behind the vital functions of a living organism come from the vital body of consciousness. Consciousness maps the vital functions in the form of the various functional organs in the physical body of the organism using its vital body.

Since only consciousness can inject meaning in the physical world, it makes sense to hypothesize that consciousness “writes” the meaningful mental programs in the brain. When we write software for our personal computer, we employ a mental idea of what we want to do in the programming. Similarly, consciousness must use the mental body to create the mental “software” (the representations of the meanings that mind processes) in the brain.

To summarize, the behavior of nonliving matter is law-like, but the behavior of living and thinking matter is program-like. Thus, logic dictates that we have both a vital and a mental body of consciousness. Consciousness uses the physical hardware to make software representations of the vital and the mental. What argument can we give for the essential existence of the supramental?

What is creativity? Only a little thought is needed to see that creativity has to do with the discovery or invention of something new of value. But what is new?

The new in creativity refers to either new meaning or new contexts for studying new meaning (Goswami 1996, 1999). When we create new meaning using old, already-known contexts, we call it invention or, more formally, situational creativity. For example, from the known theory of electromagnetic waves, Marconi invented the radio. The radio gave new meaning to a particular portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, but the context for the invention was already present.

In contrast, the creativity of Clerk Maxwell, who discovered the theory of electromagnetic waves, is fundamental creativity, because it involves the discovery of a new context of subsequent thinking or inventions.

Thus, the fact that we have two kinds of creativity, situational and fundamental, invention and discovery, necessitates the hypothesis for a supramental intellect body which processes the context of mental meaning.

Actually, the definition of creativity, if you recall, speaks of something new of value. What gives value but our feelings of pleasure and pain? So the existence of the vital body is also implicit in the definition of creativity.

A little thought will show something else. The mental body not only gives meaning to the physical objects of our experience, we also use it to give meaning to the vital body feelings. So similarly, the supramental is used not only to give contexts of mental meaning but also to provide contexts for the movement of the vital as well as the physical. In other words, the supramental intellect is the very same as what I previously called the theme body—the body of archetypal themes that shapes the movement of the physical, the mental, and the vital.

Now, what of the quantum nature of these bodies that we postulate to avoid dualism? Let's tackle the mental body first.

It has become customary in modern psychology to denigrate Decartes. But this great seventeenth-century philosopher/scientist noticed something undeniably profound about the differences between what we call the mind and what constitutes our physical body. He said that, while the objects of the physical world have extensions, localizations in space (they are res extensa), the objects of the mental world (res cogitans) do not have any extension; they cannot be localized in space. Thus, the idea that thoughts, mental objects, can be described in terms of objects that move in space, objects that have finite localizations, seemed unreasonable to Descartes. Hence, he proposed the mental world as an independent world (Descartes 1972).

It also follows from Descartes' argument that physical objects, having extension, are reducible to smaller components. The macro-physical is made of the micro, of atoms, which, in turn, are made of still smaller elementary particles. But mental objects, having no extension, cannot be reduced to micro subdivisions. The same idea is found in Indian philosophy where mind is referred to as sukhsha, which is usually translated as subtle but also implies indivisibility.15

But Descartes, profound as his ideas were, also made profound blunders. One blunder is interactionism, as we have noted many times. Another blunder is that he included consciousness as a property of the mental world. But now that we have corrected with our new science both his mistakes, can we seriously take what was profound in his thinking?

What is the difference between gross physical and subtle mental substances? One big difference is the grossness of the macroworld of our shared perception in the physical domain. We are postulating that both physical and mental substances are quantum substances. But the difference is that, in the physical world, micro-quantum objects form macro-objects. This is not so in the mental world.

Quantum objects obey the uncertainty principle—we cannot simultaneously measure both their position and velocity with utmost accuracy. Now in order to determine the trajectory of an object, we need to know not only where an object is now but also where it will be a little later—in other words, both position and velocity, simultaneously. And this the uncertainty principle says we cannot know. So we can never determine accurate trajectories of quantum objects; they are subtle by nature.

But if you make large conglomerates of subtle quantum objects, they tend to take on the appearance of grossness. So, although the macrobodies of our environment are made of the micro-quantum objects that obey the uncertainty principle, they have grossness because the cloud of ignorance that the uncertainty principle imposes on their motion is very small, so small that it can be ignored in most situations. Thus, macrobodies can be closely attributed with both position and velocity and, therefore, trajectories. Thus, we can observe them at leisure, while others are observing them, and form a consensus about them.

Another way to see this is to recognize that the possibility waves of macromatter are so sluggish that between your observation and my observation, their spreading is imperceptibly small; so we both collapse the object virtually in the same place. In this way consensus is born and with it the idea of physical reality out there, in public, outside of us.

Incidentally, this idea that the behavior of macrobodies is given approximately by deterministic Newtonian physics is called the correspondence principle. It was discovered by the famous physicist Niels Bohr. The physical world is made in such a way that we need the intermediary of the macrobodies, macro “measurement” apparatuses, to amplify the micro-quantum objects before we can observe them. This is the price we pay—losing direct touch with the physical microworld—so that we have a shared reality of physical objects, so that everybody can simultaneously see the macrobodies.

So why are mental objects not accessible to our shared scrutiny? Mental substance is always subtle; it does not form gross conglomerates. In fact, as Descartes correctly intuited, mental substance is indivisible. For mental substance, then, there is no reduction to smaller and smaller bits; there is no micro out of which the macro is made.

So the mental world is a whole, or what physicists sometimes call an infinite medium. There can be waves in such an infinite medium, modes of movement that must be described as quantum possibility waves obeying a probability calculus.

You can verify directly that thoughts—mental objects—obey the uncertainty principle; you can never simultaneously keep track of both the content of a thought and where the thought is going, the direction of thought (Bohm 1951). We can directly observe thoughts without any intermediary, without any so-called macro measurement apparatus, but the price is that thoughts are private, internal; we cannot normally share them with others.

Profound ideas give us profound understanding. Thus, the idea that we have a mental body consisting of quantum possibility “objects” enables us to understand why our awareness of mental objects is internal as opposed to our awareness of the physical, which is external.

When we act in our conditioned modality, the ego, then our thoughts, indeed, thinking itself, seem algorithmic, continuous, and predictable, which gives them the appearance of objects of Newtonian vintage. But there is also creative thought, a discontinuous transition in thinking, a shift of meaning from conditioned to something new of value. When you recognize creative thought as the product of a quantum leap in thinking, any resistance to accepting the quantum nature of thought may decrease substantially.

Finally, although normally thoughts are private and we cannot share them with one another, there seems to be compelling evidence for mental telepathy in which thoughts are shared, suggesting quantum nonlocality of thought between minds that are suitably correlated (Becker 1993). The physicist Richard Feynman (1981) showed that classical Newtonian systems can never simulate nonlocality. So perhaps the nonlocality of thought, as in telepathy, is the best evidence of its quantum nature.

Mentation, at least, is a familiar beast, and you may have already intuited, even without my prodding, that the idea of a separate mental body is justified including its quantum nature. But is there any profound justification for the postulate of the quantum nature of the vital body?

In our culture, thanks partly to Descartes, maligned as his teachings may have been by materialists before the current development of science within consciousness, and thanks partly to our familiarity with thoughts, we have always had friendship with ideas of mind-body dualism, the dual worlds of mind and physical matter. However, the same thing cannot be said of the idea of the vital body. To be sure, we sometimes are intrigued when somebody uses the words “vital energy” to describe his experiences. But we do not necessarily engage with notions of a separate vital world of vital substance; our experience of the vital energy is not confident enough.

To be sure also, biologists of the past sometimes have used the idea of a vital body and its vital force—a philosophy called vitalism—to explain the workings of a living cell. But with the advent and phenomenal success of molecular biology in explaining how the living cell works, all ideas of vitalism were banished from science. We have to look at the science of other cultures to access and examine ideas of the vital body, cultures such as the Indian, the Chinese, and the Japanese. In particular, how medicine is practiced in India and China is highly instructive as to the nature of the vital world and the vital body.

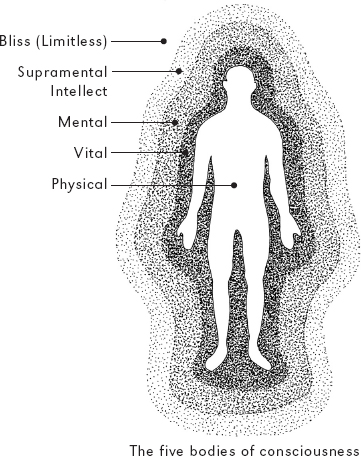

In India, yogic healing consists of a manifold approach to who we are. In the Upanishads, there is a description of five bodies of a human being (fig. 6.1). The grossest is physical, literally renewed constantly from food molecules and hence called annamaya (made of anna, food) in Sanskrit. The next subtler body is called pranamaya (made of vital energy, prana); this refers to the vital body of life associated with the movements of life expressed as reproduction, maintenance, etc. The next, even subtler body, manomaya (made of mana, mind substance) is the mental body of mind movement, thought, discussed above. The next body, called vijnanamaya (made of vijnana, discriminatory intelligence), is the supramental intellect or theme body, the repository of the contexts of all the three “lower” bodies. Finally, the anandamaya (made of nonsubstantial ananda, spiritual joy or bliss) body corresponds to Brahman—the ground of all being, consciousness in its suchness.

Fig. 6.1 The five bodies of consciousness. The outermost is the unlimited bliss body; the next body is theme, or supramental intellect, that sets the contexts of movements of the mental, the vital, and the physical. Of these latter bodies, the mental gives meaning to vital and physical movements and the vital has the blueprints of biological forms of life manifested in the physical. Finally, the physical is the “hardware” in which representations (“software”) are made of the vital body and the mind.

Accordingly, Indian medicine is divided into the study of five healing modalities: diet, herbs, and hatha yoga (asanas or postures) for the care and healing of the physical body; pranayama, the practice of which in the simplest form consists of following the inflow and outflow of breath, for the care and healing of the vital body; repetition of a mantra (incantation of usually a one-syllable word) for the care and healing of the mental body; meditation and creativity for the care and healing of the supramental body; and deep sleep and samadhi, or absorption into oneness, for the care and healing of the bliss body (Nagendra 1993; Frawley 1989).

Understand that pranayama is more than the following of breath. The Sanskrit word prana means breath, to be sure (it also means life itself), but in addition, it means modes of movement of the vital body, the body made of prana. The aim of pranayama is ultimately to access the movements of the vital body. These movements are felt as currents through channels called nadis. Two important nadis cross at the nostrils; hence, watching the breath as in alternate nostril breathing helps to veer us toward the awareness of the movement of prana.

When Western medicine came across such ideas as prana and nadi, attempts were made to understand them as some sort of physical entities. In particular, nadis were looked at as nerves, but to no avail; no correspondence was found.

The Chinese have developed the very sophisticated medicine of acupuncture, based on the idea of the flow of chi through channels called meridians. These channels have no correspondence to the physical nervous system, either. There is enough similarity of these meridians to the nadis of the Indian system (although the correspondence between the two, interestingly, is not unique) to suggest that chi is akin to prana, the modes of movement of the vital body.

The journalist Bill Moyers did a television series for Public Broadcasting Service that had a wonderful segment regarding Chinese medicine and the mystery of chi. In one segment, in answer to Moyers' question, “How does the doctor know he's hitting the right (acupuncture) point?” David Eisenberg, an American apprentice of Chinese medicine, said:

It's an incredibly difficult thing to do. He asks her whether she feels the chi, and if she has a sensation, that's how he knows. He also has to feel it. My acupuncture teacher said it's like fishing. You must know the difference between a nibble and a bite (Moyers 1993).

But it takes years to learn to feel somebody else's chi. The feeling of chi is internal, normally not a part of our shared reality. How the acupuncturist shares in the chi experience of a patient is like mental telepathy.

To me, the most interesting segment of the Bill Moyers episode came when a chi gong master demonstrated his control of his chi field (and presumably of others) which others could not penetrate with all their physical might. They attacked this slight, elderly master, but were repelled by an invisible force without any physical contact whatsoever. Was the master repelling his attackers by controlling their chi fields? It sure seemed that way. Chi gong is a form of martial arts designed for learning the control of the flow of chi in the vital body. Tai chi is a dance form with the same objective.

The Japanese system of aikido is, likewise, designed to learn and access the movement of ki, the Japanese word for the modes of movement of the vital body.

I must tell you about my first direct experience of chi (or prana, or ki). This was in 1981; I was an invited guest speaker at a workshop given by John and Toni Lilly at Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California. The East Indian guru Bhagwan Shri Rajneesh was very popular then, and one morning I was participating in “dynamic” meditation to a Rajneesh music tape—a combination of first shaking your body vigorously, then doing a slow dance, followed by a sitting meditation. I got a good workout shaking my body; it was unusually invigorating. When the music changed to signify the beginning of the slow dance, we were instructed to dance closed-eye, and that was nice.

But I bumped into somebody and opened my eyes, and lo! a pair of bouncing breasts engaged my stare. I was a little uptight about nudity then (this was my very first trip to Esalen), so I closed my eyes immediately. Unfortunately, closing my mental body was a different matter. So the mental picture of the bouncing boobs and the ensuing embarrassment and, additionally, the fear of bumping into somebody else occupied me.

When the slow dancing ended, I was very relieved. I sat down to meditate, and concentration came easily. It was then that I felt a strong current rising along my spine from my lower back to about the throat area. It was extremely refreshing—utter bliss.

Later analysis suggested that this was indeed a flow of prana, sometimes called the rising of kundalini shakti (kundalini means coiled up, and shakti means energy; thus, kundalini shakti means coiled-up vital energy or prana), actually a partial rising. In later years, I have been to workshops (in particular, one given by the physician Richard Moss) where I experienced profound flows of prana throughout my body. More recently, I have been doing practices to stabilize my experience of prana.

My experience is not unique. Many people have experiences of the flow of prana or chi or rising kundalini, and it is now one of the anomalous phenomena under intense study by avant-garde medical researchers in this country and elsewhere. (Read, for example, Greenwell 1995 and Kason 1994.)

Let's come back to theory. Can the modes of movement of the vital body—prana, chi, or ki—be described as the quantum possibility waves of an underlying infinite medium of the vital world? Clearly, since both the Indian and Chinese systems talk about pathways or channels for the flow of vital energy, vital energy must be more localizable than its mental counterpart. However, notice that the Indian pathways of nadis do not exactly match the Chinese meridians. This can be understood if the localization is not laid in concrete; so there is scope for the validity of the uncertainty principle here. Additionally, in Chinese medicine, chi is always thought in terms of complementary concepts such as yin and yang. So both uncertainty and complementarity prevail for vital energy movements suggesting their quantum nature.

Fig. 6.2 The chakras. We feel emotions in conjunction with these points in the physical body. The chakras represent the places of the physical body where representations (the organs) are made of vital body blueprints for biological form-making, or morphogenesis.

I have already argued that vital energy is experienced internally, as is the mental, although these modes are less subtle (that is, more localizable) than the mental. This further confirms the play of the uncertainty principle for these modes. I will therefore assume that the modes of vital energy, like the mental, can be described as waves of quantum possibility in the ocean of uncertainty of the vital world.

Realizing that, like thought, the movement of prana also displays both conditioning and creativity further supports a quantum assumption. The truth is that there are conditioned aspects of pranic flow with which you are quite familiar. When you feel romantic, the feelings in the region of your heart are conditioned movements of prana. When you are tense and nervous, the knot you feel in your stomach or thereabouts is another example of this conditioned movement. Likewise, it is a conditioned movement of prana if you are singing before an audience for the first time and feel the sensation of choking in your throat area. These points where we feel the conditioned movements of prana are called chakra points in the literature, according to which there are seven major chakras (fig. 6.2) (Goswami 2000). On the other hand, the previously cited rising kundalini signifies the creative movement of prana; it breaks up the homeostasis of pranic conditioning and is the source of all the creative breakthroughs that kundalini rising often initiates.

I mentioned chi gong masters before. Scientific research in China indicates that these masters are able to effect biochemical reactions in cell cultures in vitro with their chi field. If they project a peaceful chi, it increases the growth and respiration of the cultured cells; the opposite happens with destroying chi—the biochemical reaction rate of cell cultures are reduced (Sancier 1991). This suggests that the movement of chi is nonlocal, and, therefore, quantum.

Thanks to the popularity of yoga, tai chi, and aikido in today's West, the vital body and its modes of movement are a little more familiar to the popular psyche. But don't think that the idea of the vital body is “Eastern” in any sense. In a famous poem, the English romantic poet William Blake wrote, “Energy is eternal delight.” Blake was not writing about physical energy. He experienced vital energy; he knew chi.

Fig. 6.3. The five worlds in the Kabbalah. Ain Sof is the ground of being. Atziluth represents the world of pure thought or archetypes of thought. Briah represents creation (of thought). Yetzirah represents (biological) form and Assiah, the manifestation of form.

Jesus said, “My Father's house has many mansions.” He knew that we have more than the one physical body. According to the Kabbala, the divine manifestation of the one (Ain Sof, or bliss body) into many takes place via four worlds, all of which transcend the physical: Atziluth, the world of pure thought—the archetypes, or themes; Briah, the world that gives creation its meaning; Yetzirah, the world of formation or morphogenetic fields; and finally, Assiah, the world of manifestation (fig. 6.3) (Seymour 1990). It makes sense that we have not only a physical body but a body corresponding to each of these worlds.

Today's bias, thanks to our materialist pundits, is that mind is brain, although the two things are experienced quite differently. Similarly, when the question arises of whether life is entirely chemical, we expect materialist biochemists and molecular biologists to settle the issue. But actually, these issues are very far from being settled.

The mind-is-brain philosophy does not explain the simplest and most straightforward aspect of our experience, namely why the mind is experienced internally in a nonshareable way while the brain can be experienced from the outside. With the help of such instrumentation as positron tomography, anybody can look at what's happening there (Posner and Raichle 1995). We model the conditioned aspects of the mind with our computers and think that the computer (brain) is all there is to mentation, avoiding the proper study of creativity, telepathy, and spirituality—the aspects of the quantum mind.

We depend on our creativity to write innovative programs to carry out our purpose with our computers. Is there evidence for such creativity of the programmer in the evolution of life? Repeated evidence. All big changes in complexity, such as the transition from reptiles to birds or from primates to humans, is not explained by a Darwinian gradual variation/selection mechanism. Instead, they show the quantum leap of a creative consciousness choosing among many simultaneous potential variations (Goswami 1994, 1997, 2000). “Punctuation marks” in evolution, fossil evidence of periods of very rapid change, are evidence of such creative interventions (Eldredge and Gould 1972).

When we study the conditioned, programmed movements of life processes in a cell, chemistry works and we become complacent that all life is chemistry. But the philosophy that life is chemistry neither explains creativity in evolution nor how a one-celled embryo achieves a complex adult form whose integrity is a vital part of the definition of the organism (Sheldrake 1981).

Let us review the situation in regard to the question, Do we have more bodies than one—the physical? It has long been noted by philosophers that the contexts of movement in the physical domain—space, time, force, momentum, energy, and such—are quite different from, and utterly inadequate for capturing the essence of, some of the contexts important for life, such as survival, maintenance, and reproduction. A rock doesn't try to retain its pristine integrity of form when bombarded by mud that adheres to it. But throw some mud on your cat and see its reaction.

There are self-maintaining, inanimate systems with cyclical, chemical reactions that can go on and on, but there is no purposiveness in such self-maintenance. Living systems, particularly advanced ones, on the other hand, live their lives with a clear agenda. A brushfire may be said to reproduce when it spreads, but this kind of reproduction lacks the purposive evolution that is part of the agenda of the living.

And then we have physical-mental-vital contexts of movement that manifest as emotions such as desire. Can you imagine inanimate physical matter driven by desire?

Furthermore, we have mental contexts of the movement of thought, such as reflection and projection, and, finally, mental/supramental contexts such as love and beauty, that are very far removed from such physical contexts of movement as force and momentum. You may describe the eddies in a river or the play of colors on clouds during a sunset as beautiful, but the beauty is entirely in your mind.

Even greater is the difference in our experience of the physical and of the mental or vital. Physical bodies of our experience appear external to us; they are part of a shared material reality. This includes our own physical bodies which we and others can see, touch, feel. But not so with the mental. We experience thoughts as internal and private; normally, nobody else can perceive them. Likewise, your feeling of “aliveness” after a physical workout and a shower, a feeling that Easterners would say is connected with the flow of prana in your vital body, is normally your private feeling. The exception occurs when quantum nonlocality connects two people as in telepathy.

The case of emotions is interesting because, in our experience of emotions, we can clearly see that all three “bodies”—physical, mental, and vital—are involved in the experience. Notice the difference in how our experience of emotion is expressed in the three bodies. The physical signs of emotion are for everybody to see or to measure with an instrument—your face is flushed, your blood pressure goes up. And there is associated mental chatter that nobody else can hear. There is also a vital flow of chi, which is quite distinct from the physical and mental aspects of emotion, that you may feel inside if you pay attention but that remains private and is much harder to control than the physical signs.

Materialists theorize that the aspects and attributes of life and mentation emerge from the movement of molecules at a certain level of complexity. But this idea of emergent life and mind remains utterly promissory. In contrast, the idea of a separate mental body makes sense even on a cursory look at our direct experience. The pictures on the TV set are nothing but the movement of electrons; however, they tell a story because we put meaning in those movements. How do we do that? We use mental pictures to dress up the physical movement of electrons that is taking place (Sperry 1983). To be sure, these mental states may be mapped into our brain now. But where did they come from originally?

Similarly, the states of the vital body manifest the contexts of the movement of life—for example, in the structure of the morphogenetic fields for the development of adult form from the embryo. When consciousness collapses the parallel physical (cellular) state of the physical body, it precipitates a physical memory (a representation) of the state of the vital body. Isn't that how you use your computer? You start with an idea in your mind and make a representation of your mental idea in the physical body of the computer. Now the computer can be said to have made a symbolic representation of your mental state.

Somebody else could carry out a conversation with the computer maps of your mentation and may find it quite mental, quite satisfactory. It would be like conversing with Data of Star Trek: The Next Generation, all of whose data-rich responses come from his built-in programs that map the mentation of his creator. But there is no need to assume that Data has mental states or the experience or understanding of what he is talking about.16 To have mental states, Data would need access to a mental body, and for experience and understanding, he would need conscious awareness, he would have to be a self-referential quantum-measurement device.17

The Star Trek: The Next Generation shows have a running plotline of Data trying to get a chip that would give him emotion. (He even got it in one episode.) An emotion chip may be able to capture the mental component of emotion, but this is not how nature programs the vital body into the physical. Vital functions are programmed as a conglomerate of living cells that actually carry out the vital function it represents, and emotions are felt (at the previously mentioned chakra points) in connection with these organs (Goswami 2000). Also, the experience of emotion would require additional vital and mental bodies and, most importantly, consciousness to mediate and coordinate the movement of all three bodies and to experience it.

So it makes sense to theorize that there are separate and distinct vital and mental bodies that manifest the vital and mental contexts of living and mentation into content and that consciousness uses these states to map physical body and brain states that correspond to them, just as we can build computer software to map mental functions (the programs that artificial-intelligence researchers write) into computer hardware.

This brings us to the question of the quantum nature of the supramental intellect or theme body, the body of contexts—the contexts of all the other three bodies, the physical, vital, and mental. The supramental body is the most subtle of the subtle bodies, so subtle that we are not at the point of evolution yet when it can directly be mapped onto the physical. But we do have evidence for the discontinuous collapse of the supramental in fundamental creativity and evidence for its nonlocality as well.

In chapter 4, I introduced the concept of monad as the body of contexts in which we live, which would make it equivalent to the supramental intellect body in the present parlance. To fully deal with the issue of survival and reincarnation, we now must generalize the concept of monad to include the vital and mental bodies as well. And to circumvent dualism, we must recognize the quantum nature of the monad.

Both the physical body and the quantum monad (now looked upon as the conglomerate of the supramental intellect, mental, and vital bodies) are embedded in the bliss body of a transcendent consciousness as possibilities. The manifestation of possibility into actuality is only an appearance (see chapter 7). Ultimately, there is only consciousness, and there is no dualism.

The perceptive reader will notice that in this chapter we have used the ideas of the subtle worlds (vital, mental, intellect) and subtle bodies interchangeably; we have not quite succeeded in showing how we acquire individual subtle bodies without dualism. This will also be done in chapter 7.

When I speak to nonscientists about subtle bodies, they often think of the question, Why can't there be subtler and subtler substances, ad infinitum? When the physical body evolves to an adequate complexity, states that correspond to the life functions and mental functions of the vital and mental worlds can be mapped into it—this is how life and mind evolve in the physical world. Can the future evolution of more complex biological beings enable it to map worlds that are even subtler than the mental? Of course, we cannot really know the answer to that question, but I mention it here only to point out that nonscientists are quite willing to ponder subtle bodies and their ramifications. (I believe that at least one more evolution of the human being is compulsory: the evolution of the capacity for mapping the supramental intellect onto the physical.)

It is also my experience that at about midnight, especially under an open sky and with a little spirit (of the alcoholic nature) in their bellies, even hard scientists become a bit spiritual. At those moments, the idea of the spirit and its five bodies would make sense to them. Even Freud is supposed to have admitted this to a friend: “I have always lived only in the basement of the building. You claim that with a change of viewpoint one is able to see an upper story which houses such distinguished guests as religion, art, etc. . . . If I had another lifetime of work before me, I have no doubt that I could find room for these noble guests in my little subterranean house.”

But the problem is with daylight. Buoyed by the solid illusion of the daytime material reality around them, these hard-scientific types profess total disbelief in anything but matter and behave as if the existence of substances other than the physical bothers their scientific sensibility to no end. Can the concept of the subtle body compete with the persuasiveness of the solid, material reality?

The first point for you to recognize here is that words such as “substance” or “bodies” have a very different meaning in quantum mechanics than in familiar, Newtonian-classical mechanics. This is true even for physical quantum objects. “Atoms are not things,” said Werner Heisenberg, the codiscoverer of quantum mechanics. The “thingness” of our familiar macroworld arises because large, massive, macro objects camouflage their quantum no-thingness; their possibility waves spread, but very sluggishly. But in truth, as the physicist Casey Blood has emphasized, even the macroworld of our observation is the direct result of the interaction of consciousness with mathematical wave functions of potentia (Blood 1993).

It will also help to give up the Cartesian subjective connotation for the mental (and the vital) body and recognize that in the Eastern tradition, as clarified above, these bodies are defined objectively (only their experience is subjective). In consonance with that tradition, I postulate that the vital, mental, and supramental substances also obey a quantum probability dynamics describable by objective mathematics. The physicist Henry Stapp agrees partway with me. “There is no intrinsic reason why sensible qualities and the directly knowable ‘ideas of objects’ cannot be represented in precise mathematical form,” he wrote once (Stapp 1996). Is there any mathematics that describes mental movements of meaning and vital movements of feeling? Spiritual traditions talk about sacred geometries of meaning, so perhaps we should pay more attention to such things. In truth, scientific work in this direction has already begun.18

When we hear or think of other worlds or bodies, we visualize structures like Chinese boxes-within-boxes. The Upanishadic bodies are sometimes referred to as koshas—sheaths—evoking a similar picture.19 We have to eradicate such habits of conception. The four quantum worlds remain in potentia until manifested (as appearance) in a quantum measurement. There is no substantiality in any of these bodies in the sense of classical physics; consciousness gives them substance via manifestation. In other words, the experience of the solidity of a solid table is not an intrinsic quantity of matter, but is the result of the interaction of the appropriate material mathematics with consciousness. Likewise, the experience of mental meaning is not inherent in mental objects but results from their interaction with consciousness.

Furthermore, a quantum measurement always requires the physical body (see chapter 7). Thus, the subtle worlds never manifest in experience without an incarnate physical body, and they manifest as bodies that usually are experienced privately.

In this way, we have physical, vital, mental, and supramental worlds of existence in potentia, and the manifestation of physical, vital, mental, and supramental bodies occurs only with quantum collapse. Consciousness is responsible for recognizing and choosing manifest actuality from all the possibilities, physical, vital, mental, and supramental, that it has available, and for experiencing that actuality moment to moment. Only this experience is subjective and beyond any scientific treatment.

In spite of the rise of a monism based on the primacy of matter, the idea that we need explicit mental substance with mental states in order to have a mind has been emphasized by many great modern thinkers, among them the philosopher Karl Popper and the neurophysiologist John Eccles (1976). But their work has been ignored because of the use of dualism in their model. With science within consciousness, with the idea of consciousness simultaneously collapsing the parallel states of our four parallel bodies, we retain these dualists' valid point and still avoid the difficulties of dualism. And importantly, by positing that the subtle bodies are objective, we open the door for science into what, in Western tradition, has been called “the mind of God.”

To those who raise the objection of Occam's razor, the parsimony of assumptions, against the proliferation of “substance” bodies in which reality manifests, I quote Einstein. “Everything should be made as simple as possible,” he said, “but not simpler.” We must also recognize that internal consistency, objective experiments, and our subjective experiences are the final arbiter of what metaphysics believe: a material monism or a monism based on the primacy of consciousness that allows five different levels—physical, vital, mental, supramental, and bliss—of our experience.

A science based on the supremacy of matter gets bogged down in stubborn paradoxes—among them, the quantum measurement paradox—that expose the lack of internal consistency of this metaphysic. A science within the metaphysics of the primacy of consciousness resolves these paradoxes, including the quantum-measurement paradox. The present theory is the first to indicate why we experience the physical as external/shareable and the subtle as internal/private without us getting bogged down in dualism. The theory also explains the stubborn nonlocality of some of our supramental, mental, and vital experiences. This is genuine scientific progress.

By postulating, in accordance with esoteric traditions, that we have not one but five bodies that define our existence, we are enlarging the scope of our science.20 Let's now return to our main subject: how does the existence of these additional bodies, the enlarged definition of the monad, help with the fundamental question of reincarnation? Namely, what is it that transmigrates from one incarnate body to another so that these bodies can be said to form a continuity, and how does this happen?

14The Upanishads, the Zohar, and, more recently, the texts of the Theosophists all posit the existence of subtle bodies.

15I am grateful to Swami Dayananda Saraswati for pointing this out to me.

16This point is especially emphasized by the philosopher John Searle 1992. See also Varela et al. 1991.

17This point is also made by the computer scientist Subhash Kak, private communication with author. See also Kak 1995.

18For example, physicist Saul-Paul Sirag is developing a model of the mind based on group theory, a branch of mathematics. See Mishlove 1993.

19A reference to Taittiriya Upanishad (Nikhilananda 1964), where the idea of the five bodies of consciousness first appeared, will show that it is not necessary to interpret the bodies as sheaths. I am grateful to Swami Dayananda Saraswati for a discussion on this point.

20For a taste of the scope of this extended science, see Goswami (in press).