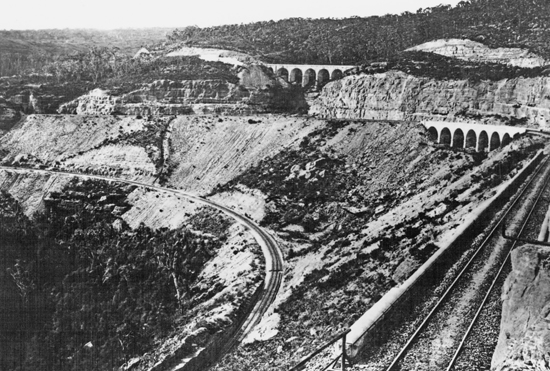

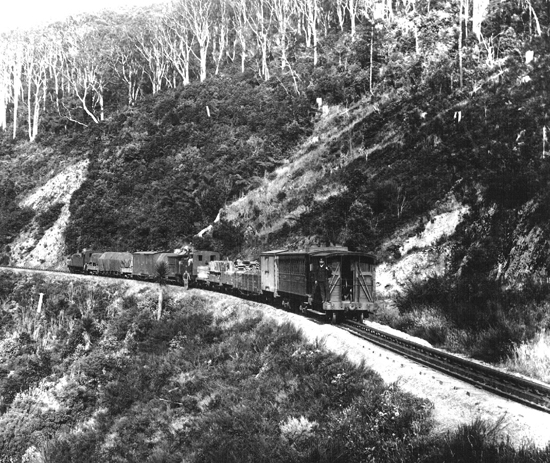

The Great Lithgow zigzag in New South Wales, Australia in the 1870s.

In 1849 the Melbourne Herald listed the benefits that railways would bring to Australia:

No more sticking in the mud then, no more badgering about the condition of the roads, no losing of bullocks, nor plundering of bullock-drivers, no leaving grain in the ground to rot, or wool on the way to spoil with rain, no escaping of prisoners under escort, no stopping the mail by bushrangers, no being at the mercy of servants for want of change, no dying for want of a doctor, no broomstick marriages for want of a priest, and no loss of time, money and patience, by detention in town, beyond the time absolutely required for the want of business.

If it does rather overstate the case for the virtues of rail travel, then it was doing no more than many another polemic on the subject had done in the past, and would do again in the future. What is remarkable is how little time had passed since the first settlers arrived in the colony before this absolute need for a rail system was perceived. It was only in January 1788 that the first convict ship dropped anchor in Botany Bay and a small party sailed north and discovered ‘the finest harbour in the world’. The description was Arthur Phillip’s, a retired naval officer who had been appointed Governor-in-Chief of New South Wales. He called the natural harbour Sydney Cove. Phillip had come to oversee a penal colony; there was little thought of trade. Future prosperity and transport meant little more than the packing off of prisoners from Britain. The indigenous population had no roads, no bridges. No one knew what lay in the interior, no one had even the faintest idea how big the place was. It was only with the first circumnavigation in 1802-3 the settlers became aware that this was not a country, but a vast continent. It is a mark of the extraordinary vigour that characterized Australian development that it took little more than half a century from tentative beginnings in an unknown land before the settlers were demanding railways, the most potent symbols of the modern world of commerce and industry.

The argument over convicts was to last for forty of those years: should they work for free settlers or for the government? Would they ever be allowed the same rights as freemen? What status would their children have? These were serious issues in the strangely unbalanced county of New South Wales, which in 1828 was recorded as having a total population of 36,598 of whom 16,442 were convicts and only 1544 women. The other pressing problem was one of how to prosper in the new land. In 1813, three explorers – Blaxland, Wentworth and Lawson – found a route through the Blue Mountains and looked out on a seemingly endless plain of good grazing land. One answer to future wealth had been found – sheep. And all the time the settlement was expanding. In the 1830s plans were laid for a new settlement in the Cape St Vincent area. The South Australian Land Company was formed and in 1834 South Australia became a province in its own right, with a capital at Adelaide. It was in New South Wales and South Australia that the railway movement began.

The Great Lithgow zigzag in New South Wales, Australia in the 1870s.

Although the two provinces had their own governments, there was a general understanding that it made sense to work towards a unified railway system for the whole country. In 1848 the two legislatures took the obvious step of settling for 4 ft. 8½ inches on the rational grounds that as Australia had no manufacturing industry of its own, everything needed for railway building would be brought across from Britain, and life would be simpler, and cheaper, if the principal British gauge was used. The argument, indeed, seems so sensible that it is difficult to see what could be said against it, and it had the strong support of the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, William Gladstone. He reinforced the argument by pointing to the mayhem of the gauge war in England. Nor were there other serious precedents to follow in Australia. There was a tramway, built on the English model, that carried, appropriately enough, coal from the mines to Newcastle on the coast; and Tasmania had a wooden railway which at a shilling a time took passengers across the Tasman Peninsula to Port Arthur penal settlement. The former used gravity for power, and the latter used convicts, who pushed uphill and acted as human brakes going downhill. Neither of these needed to have much influence on the rational planning of a national steam railway system. Everything seemed set fair for a period of logical development. Then the Sydney Railway Company appointed F.W. Shields as chief engineer.

Shields was an Irishman who had worked with Vignoles. He took the view that in an overcrowded little island like Britain, the modest gauge of 4 ft. 8½ in. might be adequate, but with all the vast spaces of Australia to build in, a more generous view could be taken. He persuaded the Board to adopt the Irish gauge of 5 ft. 3 in. South Australia, willing to be accommodating, went along with the change, and put in orders for locomotives and rolling stock. In the meantime, the Sydney Company found itself short of funds and asked Shields to take a cut in salary. Grievously offended, Shields at once resigned and his place was taken by the Scottish engineer, James Wallace, who was as devout a believer in the Stephenson gauge as Shields had been in the Irish. Plans were reassessed in Sydney and New South Wales, but neighbouring Victoria and South Australia had already invested heavily in the 5 ft. 3 in. gauge and were in no mood for expensive changes. The war that Gladstone had warned against had come about. To make matters worse, when Queensland began building lines, much later on in the 1860s, it was decided that cash was paramount, and they opted for a cheap 3 ft. 6in., also well fitted to the difficult terrain. Australia ended up, like India, with three systems, broad, standard and narrow. No doubt it all made sense at the time.

In the 1850s, the whole nature of railway building, and of Australian society as a whole, changed very suddenly. A digger called E. Hargraves came to Australia from California and thought the landscape very like that of the gold fields he had recently left behind. He found gold and set off a gold rush that led to the discovery of the great alluvial deposits at Ballarat. Everyone, it seemed, headed for the gold fields – even sea captains could be seen at work; they had little choice since their crews had already deserted. For a time there was no labour for railway building, but in the long term it brought a flood of immigrants. The new Australians felt quite able to settle the land for themselves and neither needed, nor wanted, convict labour. Hence the transportation of convicts came to a halt. The immigrants did, however, need better transport, to serve both the gold fields and the rapidly growing communities.

Once the first excitement of the gold rush had died down, railway work was resumed. The broad gauge track was first in use when 2 miles of track was opened from Melbourne to Port Melbourne. It was hurried along in order to get supplies to the goldfield. A year later, the 13-mile route from Sydney to Parramatta followed. The Sydney line was not a huge success and was taken over by the state, renamed the Great Western Railway and gradually extended westward to the foot of the Blue Mountains. John Whitton arrived from England in 1857 as chief engineer for all the New South Wales lines; he was to stay on in Australia to oversee more than 2000 miles of track construction, including an amazing 289 miles in one year. There would have been no possibility of building at such a rate with the meagre supplies of local labour, and Whitton turned, as so many others had done, to Thomas Brassey.

Brassey himself never went to Australia, but handed the job to one of his agents, Samuel Wilcox, who had worked with him on the Paris and Caen Railway. Wilcox set off for New South Wales in 1859. At first local men were taken on at wages varying from 7s. a day for labourers to 12s. for skilled tradesmen. It was considered a very generous wage. Wilcox was closely questioned on the standard of living by Brassey’s biographer, Arthur Helps:

Q. Take a man spending 10s. a week there; if he had been living in England would it have cost him 8s.?

A. He would get as much bread and meat there as he could eat, but here he could hardly look at it. As long as a man with a family is kept from drink there, he can, in a very short time, get sufficient money to start and buy a piece of land, and become ‘settled’.

Q. May it not be said that a good stout labourer in England could not live as a navvy for less than 8s. a week?

A. Not living as a navvy does. I do not think that he could live on 8s. a week; living generously as a navvy has to live. Out there he could live very much more amply supplied at 10s., and really on less than 10s. In the case of some of the men I have known camping out together, the rations did not come to more than 8s. 6d. per week.

Unfortunately, the rosy picture of independent labourers saving up for their own land does not take account of the navvies’ habit of taking the occasional tipple.

Q. Did you find that a working man, placed as he appears to be in Australia in exceptionally advantageous positions with regards to means, drinks more?

A. Yes; he does.

Q. In short, there is a great deal of drunkenness there?

A. Yes; and the drink is more expensive; they charge you more there; they charge you 6d. for a glass of beer, and they charge for a bottle of beer 2s. 6d., which you get for 1s. in England.

It was soon obvious that more men were needed, and Brassey sent his recruiting agents to Scotland. This was a period when the government was trying to encourage emigration, so that Brassey fitted the men out at an average cost of £5 each, while the government contributed a further £12 for the passage. Brassey had no contract with the men, but was on pretty firm ground as Wilcox explained:

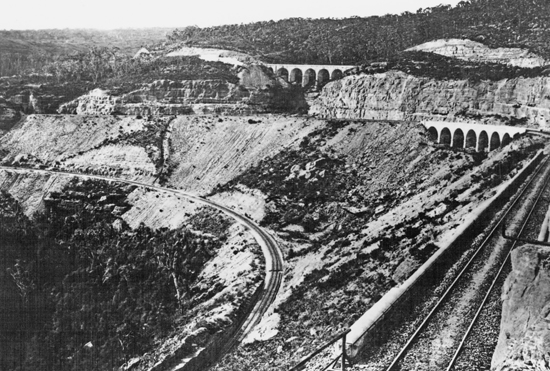

Launching a caisson out into the river during the construction of the Albert Bridge, Australia in the 1890s.

Having men in the country, we knew that they must work for somebody; and we also knew that we were in a position to pay them as much as, or more than, any one else. They were at liberty, on landing, to go where they liked; and some few, not a great number, but some few, never came to the works at all; but we found that we got a great part of them, and more came out by other ships.

Initially, Brassey helped pay for 2000 Scots to travel to Australia.

Whitton having pushed the route on to the foot of the Blue Mountains was faced with a climb to the ridge at 3336 feet – not something where his experience on the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway would be of a great deal of use. Early suggestions were for a charge up the mountain at the ludicrous slope of 1 in 20, later modified to a rather more modest 1 in 30, though that was only possible if a 2-mile tunnel was blasted half way up the mountain. In the end, Whitton settled for a zigzag which involved the construction of a large number of viaducts and the blasting away of vast quantities of rock. The largest single mass, estimated at 45,000 tons, was reduced to rubble by an explosion detonated by the Countess of Belmore, wife of the Governor-General. Thanks to the zigzag, with its two reverses, a very reasonable 1 in 60 was maintained, but it gave spectacular views as the track made its way to the summit up a narrow, spiny ridge. Having got to the top, there was no comfortable plateau, but instead a switchback ride over the mountains, before plunging down the other side in the even more exciting Lithgow zigzag.

Not suburban England in the nineteenth century, but an outback station in New South Wales.

Railway building in Australia was not a question so much of joining centres of population as of pushing out a route into the wilderness which settlers could follow. One English engineer at least was unimpressed by the process. C.O. Burge had moved on from working in India (see Chapter 5) and arrived to work in New South Wales, surveying a new route. ‘The district was one which was called populous, yet on the whole of about thirty miles of the proposed railway there was only one squatter.’ Conversation was less than amusing: ‘If you cannot talk sheep, you are out of it.’ And when he did reach towns, he found them even less impressive than the outback.

Our next move was to an up-country township to take charge of the construction of another line; and here I would remark that, having seen since a vast number of Australian country towns, the deadly, drab, dull similarity of one to the other I never saw equalled except in a sack of peas. At a later period, some of my duties involved fixing the site of new townships in the then uninhabitable Bush at suitable distances on projected railways, and as they were to be on the terrible chessboard plan, and would no doubt be built in the usual formal style, my artistic conscience must bear the weight of having assisted in the extension of such hideous-ness. The style consists of straight wide streets, flanked with brick barrack-like houses roofed with corrugated iron, with verandahs painted with yellow and red stripes covering the footways, and supported by posts at edge of the latter, the court house, banks and hotels being slightly more pretentious than the ordinary shops.

Lines were soon spreading south as well as west out of Sydney, while at the same time the broad gauge routes were developing in Victoria. Here work proved even more difficult than it had in New South Wales, with conditions more like those of the jungles of Africa. Thomas Griffin surveyed one 14-mile stretch of line: the work was to take him two whole years. He had to carve a way through almost impenetrable undergrowth, hacking through dense forest and clearing fallen trees. The land was impossible for pack animals, so everything had to be carried on the survey party’s backs. In 1883 the routes from Victoria and New South Wales met at Albury, when for the first time the inconveniences of a break of gauge made itself felt. Everything, passengers and freight, had to be moved from one train to the other. In 1887, the Victoria and South Australian Railways were also united.

There was still one gap to be filled in New South Wales. The line running north from Sydney stopped at the Hawkesbury River. Here passengers were ferried across on an aged stern-wheeled paddle steamer. After that they could continue on their journey north to Newcastle and Queensland. There had already been a number of iron bridges built in Australia, which had been designed and prefabricated in Britain. The Murray Bridge, for example, was designed by the UK consultant William Dempsey with ironwork supplied from Crumlin in Ebbw Vale. However, rather as the Canadians had done, the Australians began to have doubts as to whether the British were always the best people to turn to for design. Other countries, notably America, had conditions much more similar to those of Australia: the bush has more in common with the prairie than it has with the neatly hedged fields of Surrey. Not only that but the collapse of the Tay Bridge in 1878 severely dented the old country’s reputation for unmatched excellence. It was Henry Mais, a Bristolian who had begun his working life on the GWR, who encouraged the spread of American techniques. He had come to Australia in 1850. After a somewhat varied career in New South Wales – resigning from the Sydney Railway Company in 1852 and being sacked from the Sydney waterworks for gross misconduct – he moved to Victoria. As part of his railway work, he undertook a world tour to look at how others were tackling production problems. He returned full of enthusiasm for American ideas, and these notions soon spread through the Australian engineering community.

When it came to the Hawkesbury River crossing, the work was put out to international tender, with a very distinguished committee vetting the applicants. These included W.H. Barlow who was responsible for the second – successful – Tay Bridge and Sir John Fowler of the Forth Bridge and the Severn Tunnel. They awarded the contract to the Union Bridge Company of New York. Even so many parts ended up being made in Britain, and CO. Burge was appointed as one of the resident engineers in charge of the work on site. It was certainly an imposing affair, with seven spans, each of 410 feet, and a total length of 2896 feet. Furthermore, space had to be allowed for small steamers to pass underneath. Burge and his associates were faced with the problem of making piers that had to go down through 40 feet of water, after which instead of reaching a good solid foundation they met mud, over 100 feet of it. The traditional method of making a coffer dam, pumping it out and building the pier inside, was clearly impossible. Instead they decided to make a 150-foot high cylinder on the bank, sink it down through the mud and fill it with concrete. This was easier said than done: there was no way a tube of that size could be towed out, raised to the vertical and sent straight down. No system then available could control the accurate movement of such a huge structure through swirling water and cloying mud and then settle it down with perfect accuracy. The whole operation would have to be carried out a section at a time: sink one bit, add another on top, sink that and so on. Burge explained how it worked in practice:

To understand the shape of the caisson and the operation of sinking it, the reader should imagine for the bottom length a top hat without its crown and brim, and inside it three vertical tubes each about the diameter, proportionally to the hat, of a small coffee-cup. Unlike the cup, however, the tubes must be supposed to be bottomless and splaying out like a trumpet-mouth below, so as to meet the bottom edge of the hat, forming a sharp edge. Such, on a very large scale, was the bottom length, or shoe as it is called, of the caisson. This shoe was floated out slightly weighted with concrete, to the exact site of the pier for which it was destined, and from the hold of a ship anchored alongside, more concrete in a liquid state was poured into the space between the outside of the tubes and the sides of the caisson, the weight of this concrete causing the shoe to sink to the bottom of the river. This done, the next thing was to get the structure down through the mud, and in order to do this, the mud had to be got out of its way. It was for this purpose that the tubes were provided which, it will have been noted, were as yet not filled with the concrete which was all round them. Specially shaped dredging buckets, or grabs as they are called, were then let down inside the tubes, and from their peculiar action forced their massive jaws into the mud and drew it up by means of steam hoists, this going incessantly day and night concurrently with the concrete filling and weighting, until the great mass was sent down to its final resting-place, in one case 162 feet below the water-line. The tubes, which were, of course, built up simultaneously with the sides of the caisson, were then filled with concrete, so that there was a solid mass of this material from the hard bottom up to the water-level, upon which the stone piers above water were subsequently built. In this bridge, therefore, what is visible to the spectator, large as that is, is only about half of the entire structure, the other half being sunk under water.

Stopping the train at a remote Australian station, by holding out the disc by day or a lantern by night.

The hardest part was manoeuvring the caisson into position. On one occasion the giant cylinder was caught by a sudden rising wind. The tugs could not hold it and it set off majestically for the open sea: fortunately the wind dropped, more tugs were called up and the errant caisson retrieved. Having finally got it into position over the spot it still had to be sunk with considerable accuracy, as girders each 410 feet long and a thousand tons in weight then had to be set in place on the bearings at the top. Even when that was achieved, the girders themselves still had to be raised into position. Once again the usual practice of erecting a temporary timber staging between the piers was useless thanks to the deep mud and fast currents. Burge goes on:

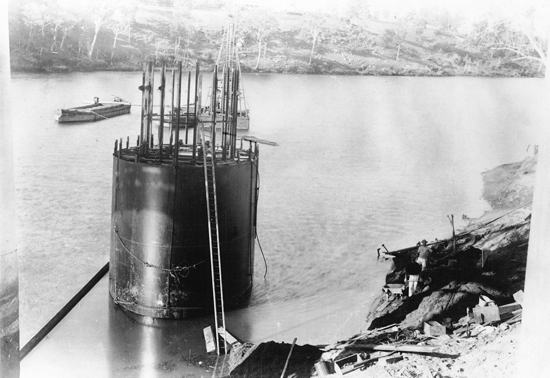

The locomotive on the Victorian Railway was designed in Britain but built in Belgium

The plan adopted was to construct and float in shallow water adjoining the shore an immense pontoon of timber, somewhat less in length than a span of the bridge, and to erect on it a scaffolding up to the same height above low tide as the top of the bridge piers were over low water. This done, while still at the moorings along the shore, the girders were put together on the top of the scaffolding with their ends projecting. When this was complete, and when a favourable condition of wind and current existed, the great craft with its top-heavy load was towed out by a sufficient number of steamers to the span for which that particular pair of girders was destined. The operation was so timed that on arrival between the piers high water would occur. The whole construction would then gradually sink with the falling tide until the projecting ends of the girders rested in their places on the pier, and the pontoon and staging sinking further would become free from their great load and be towed back to shore to serve the same purpose for the other sets of girders – seven in all.

This was anxious work, but only once did the whole process almost end in disaster, with the span nearest the shore at the southern end.

The pontoon with its load was successfully navigated to near the site, and all was going merrily as a wedding bell, when great delay occurred in trying to warp her round. The hitherto rising tide had begun to turn, and before the manoeuvre was complete one end of the pontoon got aground on a sunken rock, the rest of it being in deep water. For many hours all efforts to draw her off failed – efforts stimulated by the possible serious consequences of failing to do so, for with the tide still falling the floating end would gradually sink more and more, the other end remaining stationary; and unless the slope at low tide was still insufficient to cause it, the great girders of one thousand tons weight would slip off into the deep river. In such case they would be utterly lost, not only by smashing themselves to pieces, but by being sunk in one hundred feet of mud, and nothing that could be done would have held them back. Moreover, if the whole vessel with its load had slipped off, destruction would equally have occurred, as the top-heavy character of the loading was only suitable for quiet movement, and not for the violent plunge downwards into the water which this result would have caused. The loss in a moment of time would have been enormous, besides causing serious delay in the opening of the bridge. The engineers and contractors’ representatives stood by on shore absolutely helpless, only trusting in the possibility of the tide turning before the steepness of the inclination of the girders would have been too much for their stability. Their hearts almost stood still as the time for low tide indicated by the almanac approached. The situation seemed desperate; great creaks and groans were heard as if the mighty structure was straining all its muscles, so to speak, to save itself, when, just as it was thought that all was over, the witching time of low tide arrived, the crisis was passed, and the girders still held fast. A few inches less of water and the newspaper posters of the world would have been blazoned with the disaster. As the tide rose, the pontoon again lifted itself level, and when high water occurred she was afloat end to end, and was safely brought into position.

Even at this distance in time, reading Burges’ account still makes one gasp in astonishment at the sheer audacity of the plan. In the mind’s eye one can see the tottering array of scaffolding with its massive load being edged out into a fast-flowing river to be positioned with inch-perfect accuracy between the tall piers. It is amazing that anyone could conceive of such a plan – even more amazing that it worked.

Burge went on from Hawkesbury to look for new railway routes, often through the most difficult territory. In one section he had to cut through scrub hung with creepers that clung tenaciously to the traveller and drew blood: the Australians called them ‘lawyers’. His first journey was of 640 miles, during which he was trapped for a week by floods, marooned in a pub. As well as deciding on a line, he also had to find station sites. At one stop the local mayor asked if he could call with a delegation. Burge waited, but no one came. The next day the mayor sent an apology. They had stopped off for a beer en route and it was, of course, unthinkable that they should move on until everyone had bought a round. There were fourteen in the delegation. On the whole, Burge seems to have enjoyed his time in Australia.

To the north of the Hawkesbury River in Queensland, engineers found quite different problems to those that faced the pioneers of Sydney. Brisbane had only been founded in 1824 and here, 500 miles away from Sydney at the edge of the huge, virtually unopened spaces of the Northern Territory, thoughts of gauge breaks and unified systems must have been far from anyone’s mind. There was, however, once again an imperative for building, with the discovery of gold in the Golden Mile that stretched from Kalgoorlie to Boulder. Fitzgibbon, the first engineer to consider the problem, suggested a narrow gauge, but it was his successor W.T. Doyne, who had worked with Brassey in the Crimea, who successfully argued the case. He began by setting out quite frankly that the proposed 3 ft. 6 in. gauge was second best. It would mean less powerful locomotives and a poorer surface, but he then went on with admirable pragmatism to argue the case that second best is a good deal better than nothing at all.

The position of Queensland appears to me to be simply this. It possesses a great territory inland which is cut off from the ports on the seaboard by mountain ranges, which have to be crossed by any system of communications which may be adopted. The present means of the colony are inadequate to provide a system of broad-gauge railways, while the wants of the community demand some power superior to the bush-tracks of transit. A medium course has, therefore, been introduced – I think, wisely. A railway is being constructed at a moderate cost which will amply meet the needs of this community for many years to come, which is perfect as far as its powers extend, and will, I have no doubt, act as a pioneer to develop the resources of the colony, and enable it to carry out superior works when necessity demands them, without having in the first instance loaded it with the incubus of debt which would retard its progress in other matters.

Peto and Betts were to take one contract in Queensland for a line across the Great Dividing Range from Ipswich to Toocoombs. The consultant engineer was Sir Charles Fox, with Abram Fitzgibbon as the man on the spot. It was a fierce line of steep grades – up to 1 in 54 – tight turns and the long Victoria tunnel to pierce the summit ridge. Hardware and structures of all kinds, including prefabricated stations, were sent out from England, together with locomotives and rolling stock. By now, however, there was a local labour force available, and 800 men were recruited from inside Australia. The engineers complained, as engineers always did, of poor work and slow work, but the line was ready in three years. Local men could do the job – and in future no Queensland contracts were to go to England. Australians could build their own railways.

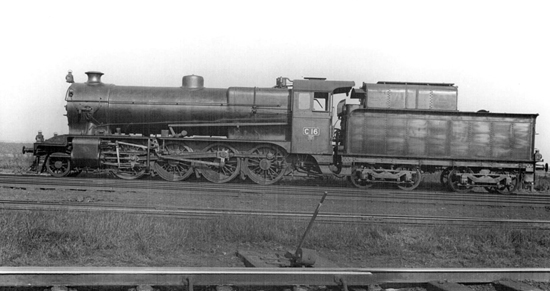

This immense oil-burning 2-8-0 was built for Australia at the Vulcan Foundry in Newton-le-Willows in Lancashire

Australia prided itself on being, and proved to be, a land of opportunities for individuals with the energy and drive to grab them. Richard Speight came to Australia in 1864 as a railway administrator and engineer after an early career spent on the Midland Railway in England. A stout, balding, heavily bearded man, he appeared the very model of Victorian probity and respectability; yet he used his post in Melbourne to please venal politicians rather than to serve the public. He built a station at a cost of £4000 to serve a country racecourse where no race was ever held. He ran an express train from Melbourne to Bendigo though there was never the remotest chance of there being enough people wanting to visit Bendigo to make it pay. But the politicians of Bendigo were pleased – and showed it. Friends and relations of prominent men were given jobs and when they were fired for incompetence, Speight took them on again. His land purchases were notorious, paying as much as ten times the true value. The press became ever more vociferous, until at last he was forced to resign. Even then the company paid him £5250 in compensation, which he promptly used to sue the papers that had brought him low. He paid out around £3000 in legal fees and, in a hearing that lasted 86 days in September 1894, he received the judgment in his favour. It was a sorry triumph: the jury awarded him one farthing in damages and no costs. It was a squalid episode in the otherwise decent tradition of British railway building in Australia.

Tasmania offered an even more mountainous terrain than the worst of mainland Australia so that when the Launceston and Western Railway Company began to build the first line they had no hesitation in opting for the 3 ft. 6 in. gauge. The line, opened in 1871, set the standard for the island, though in the very worst areas the gauge was dropped to 2 ft. Hauling heavy trains on narrow gauge tracks was a problem that troubled operators the world over. It was the very nature of such lines that they would have tight curves which would seem to rule out the use of big, powerful locomotives. A solution occurred to the inspecting engineer for New South Wales, William Garratt. His design called for an articulated locomotive with two power units fed by the boiler. The result looked as if the designer had begun with a conventional locomotive with driving cab, boiler and chimney, with the only difference being the positioning of the cylinders at the back, under or behind the cab. There, however, convention ended, for in front of this was a strange assemblage, with a second power unit and a further set of cylinders. The first design called for a 2-4-0 + 0-4-2 wheel arrangement. There was plenty of power, and the locomotive could ‘bend’ in the middle where the extra power unit was attached. Garratt came to England and showed his designs to Beyer, Peacock of Manchester. They developed the design commercially, and the very first Garratts were sold to Tasmania for use on the 2 feet line in 1909.

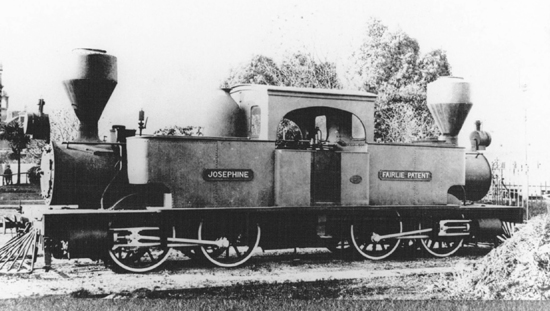

A double-ended Fairlie locomotive built by the Vulcan Foundry in 1872, It became Locomotive No.2 on the Dunedin & Port Chalmers Railway, New Zealand

The Garratt proved an immense success, not only in Tasmania but on narrow-gauge railways throughout the world. A series of tests in South Africa in 1921 showed it to pull heavier loads at higher speeds than its rivals, including the majestic compound Mallet. The tester noted tersely, ‘The Mallet is 46 tons heavier than the Garratt and pulls less’. Weight was very important on the light track often used in poorer countries, and, being articulated, the Garratt could spread the load over a large number of axles. The Kenya and Uganda was supplied with immense 4-8-4 + 4-8-4 engines, giving a total of 16 axles to bear the weight. Garratts could also be built for speed. Tasmania was once again the testing ground in 1912 for the early high-speed Garratts, this time for use on the 3 ft. 6 in. line. A 4-4-2 + 2-4-4 engine, with four cylinders on each bogie, achieved a speed of 55 m.p.h. which is good going on a narrow gauge track.

If Tasmania presented problems, then a contour map of New Zealand looks like the design for a railway engineer’s nightmare. It is every bit as bad as it looks, so bad, in fact, that although at its narrowest South Island is scarcely a hundred miles across there was no rail connection between the east and west coasts until 1925, and that was only made possible by boring the 5½-mile Otira tunnel. It was not only the difficult, mountainous country that made for slow railway development – the development of settlements was equally tardy. Although James Cook had arrived in 1769, by 1835 there were still only 2000 Europeans in the entire country. Official colonization acts set up Wellington and Nelson in 1840, Otago in 1848 and Canterbury in 1850. The infant settlements, however, did show an early enthusiasm for railways.

Construction started in South Island. In the 1850s, work began on a road to link the port of Lyttelton to the interior, and construction had hardly got under way before critics were saying that it would have been more sensible to build a railway. These first railway rumblings were heard just four years after the colony had been officially founded. Not to be outdone, the citizens of Wellington on North Island began agitating for a line to link them to the interior. But it needed more than the clamour of a handful of possible passengers to justify the expense. Freight was to supply the demand. In 1852, the settlers at Nelson in the north-west corner of South Island began exploring Dun Mountain and found promising deposits of copper ore. In 1854, W.L. Wrey came to London to raise capital for a mining venture. When he returned to New Zealand with the cash, he soon found himself being given the job of raising more money, this time for a railway from mine to port.

The parent company, the Dun Mountain Copper Mining Company, was incorporated in London and this time it seemed a good idea for someone to go out from England to visit the works. The man given the task was Thomas Hackett who found that the miners were looking for the wrong mineral: the copper deposits were disappointing but there were good supplies of chrome. Chromium compounds were widely used in printing coloured patterns for the textile industry. The copper mine became a chrome mine and the company approved the railway which was given official blessing by the Nebou Provincial Council in 1858. Rails, iron sleepers and wagons were sent over from England, to be followed in 1860 by W.T. Doyne, already mentioned for his work in Australia, and G.C. Fitzgibbon who had worked in Canada and Ceylon. The start of work was held up by the central government whose sluggish deliberations meant that final approval was not given until 1861. Officially, this was a railway designed for use by steam locomotives; in actuality, it was an old-fashioned tramway. The easiest gradient was 1 in 76 and for nine miles it was a precipitous 1 in 20. The 3-foot double track was initially worked as a system down which loaded trucks descended under gravity and empties were hauled back up by horses. Whether in time it might have been made over to steam, as similar lines – such as the Festiniog – had been in Britain, will never be known. The little line had hardly got started when Civil War broke out in America, the supply of cotton for the mills of Lancashire dried up and the demand for chromium dyes disappeared. The mine and its railway were closed and there was still no steam locomotive in New Zealand. It had, however, shown that railways could be built in the country and when the Wellington Council began investigating the possibilities of promoting a line, they specified one ‘similar to the Dun Mountain Railway’, though they did increase the gauge to 3 ft. 6 in. and envisaged locomotives being used from the very beginning. They made a declaration that epitomized the reasoning behind railway building in South America, Canada, Africa, in fact everywhere that aspired to extend settlement out into the wild countryside: ‘Let the country but make the railroads, and the railroads will make the country.’

The next development came at Christchurch. The port was at Lyttelton Harbour separated from the town by the Lyttelton Port Hills. The road had been built in 1852 and the provincial government had been pushed into making a promise that, at the very least, they would give serious consideration to a railway as soon as funds permitted. Local businessmen led by William Moor-house – who earned himself the nickname ‘Railway Billy’ – began arguing ever more urgently for a railway to speed up development of the settlement. In 1858, the transport commissioners bowed to the pressure and wrote to Robert Stephenson to ask if he would take on the job. By then Stephenson’s ill health had caused him to give up virtually all railway work – he was to die in 1859 – but he recommended his nephew, George Robert Stephenson, for the job. Stephenson went out to New Zealand to survey the difficult route which included a tunnel through hard rock. It was to be built to the Australian broad gauge of 5 ft. 3 ins. At this stage no one seemed to be thinking very seriously about standardization – so far three railways had proposed three gauges, 3 ft., 3 ft. 6in. and 5 ft. 3 in. Looking at this mountainous country as a whole, no one could surely expect to cover it with the wider gauge lines, but then, who would have expected a Stephenson of all people to appear as a champion of the broad gauge! The contract was given to Smith and Knight of Westminster, but when they arrived and took test borings along the line of the tunnel, they immediately asked for the price to be increased from £235,000 to £265,000. Stephenson refused, and the contract went instead to Holme and Co. of Melbourne. When one considers that railway building in Australia was very much in its infancy, this was a bold decision. The experienced British contractor had said that no profit could be made at the old price given the nature of the rock through which the tunnel had to be driven. Events were to suggest it was a wise decision.

Progress on the tunnel was desperately slow: 50 yards a month at the very best, a paltry 10 yards at the worst. They were destined to slave away in the hills for years. No one was prepared to wait for ever, so a temporary line was opened from a riverside wharf at Ferrymead. It helped in providing a supply route to the tunnel and enabled the New Zealand railway system to open its first steam service. On 6 May 1863 the first locomotive was delivered from Slaughter, Gruning & Co. of Bristol. It was a simple 2-4-0 tank engine, the very model of good British design from its shining brass dome to its 6-foot-diameter drive wheels, but differentiated from its English cousins by the broad spark-arrester chimney, an essential feature of all wood-burning locomotives. Still, however, the men slaved away in the tunnel which was not opened until 1867.

The Fell engine climbing the Rimutaka incline in New Zealand, 1878: the central rail that was gripped by horizontal wheels can be clearly seen.

Meanwhile, the line was being extended north and south along the coast from Canterbury, crossing two broad rivers in the process, the Raikaie and the Rangitate, and acquiring a new and suitably grand name, the Canterbury Great Southern Railway. By 1870, the route to the north was open as far as the Selwyn River, and a certain amount of work had been done to the south of Canterbury. But this early experiment in broad gauge construction was to be short-lived: the pioneering line from Ferrymead, the first to open, was also the first to close. It was a muddled time, when no one knew quite what to do. There was no lack of enthusiasm in New Zealand, but there was a great lack of experience. The young country was open to new ideas, but was not always able to distinguish between the innovative and the eccentric. In 1863, an American engineer, J.R. Davies, demonstrated a cost-saving railway using native timber instead of imported iron. The locomotive literally blazed down the tracks, the sparks from the engine leaving a trail of burning rails behind it. All very entertaining, but not very helpful in building up a sound railway system, and it was not until the 1870s that a really solid basis for expansion was established. What was needed were not wild, innovative ideas but a realizable vision of the future. That needed a man who could combine imagination and practicality. New Zealand found such a man in Julius Vogel.

The underside of a Fell engine, showing the gripping system on the central rail

Vogel had left London to join the great gold rush to Victoria and had then moved on to New Zealand where he became involved in politics, and ended up as government treasurer. What he proposed was a rail-building system far more ambitious than anything tried in any other developing country. The government should pump money into construction, and as soon as lines were open use the revenue to pay for still more building. His plan was to borrow £10 million over a period of ten years, using the public land along the new transport routes as security. There was to be nothing fancy about the programme. It could all be summed up in one simple phrase: get as far as possible as cheaply as possible. This was the old cry again. Expand the railway, open up the country and you encourage immigration: ‘… the railroads will make the country’. Given the usual reaction of politicians and authority to innovative ideas, the surprise is that he was not only listened to, but his advice was largely followed. A public works department was established, a general Railways Act was passed, authorizing the new department to raise money and, somewhat belatedly, a Gauge Bill was introduced that would settle the gauge for future railways in the country. Almost equally surprising was the fact that the local politicians freely admitted their ignorance of railway affairs and turned to the English engineers, Charles Fox and Son for practical advice. They recommended the Australian narrow gauge of 3 ft. 6 in. which they already had experience of building. The advice was accepted, even though it meant tearing up the existing track and relaying it. At least New Zealand now had a national standard, putting the country one up on its larger neighbour.

Vogel began by promoting lines based on Dunedin on the east coast of South Island, starting with a short route up to Port Chalmers. If New Zealand’s first mineral railway had echoes of the Festiniog in North Wales, then the new line also had its similarities with that innovative route. Long before Garratt had found his solution to providing enough power to haul heavy loads on narrow-gauge tracks, Robert Fairlie had come up with his solution among the mountains of Wales. It is as well to remember that the decision to adopt the narrow gauge at all was a bold one, for these little railways had all been horsedrawn right up to the 1860s. Fairlie’s engines are extraordinary creations, looking like the result of a nasty accident when one conventional engine has reversed into another at speed. Starting at the front is a conventional boiler and engine unit, followed by the cab, after which comes a second boiler and power unit. There is plenty of power, and the two halves are each mounted on bogies to help with tight curves. In 1873, a double-Fairlie worked a train out of Dunedin, just four years after the prototype had run on the Festiniog.

The 1927 Peckett of Bristol engine running on the Bay of Island Vintage Railway in New Zealand

As in Australia, not everyone was happy with this reliance on British expertise, manpower and hardware. There were even more complaints when the next 159-mile route was let to John Brogden & Sons of London for a contract which was to include the provision of rolling stock. What rankled with the New Zealanders was the fact that locals were not given the chance to bid. There were reasons, and sound reasons at that. Although the government was guaranteeing the costs, money still had to be raised on the London markets – New Zealand was too young a country in terms of finance to provide that much cash on its own. It was also still generally believed by many that British expertise was unmatched. And finally, the contractor was expected to bring over a contingent of big, brawny navvies who would stay on as settlers, just as Brassey’s men had in Australia. The line was built. However it marked a shift away from British dominance.

Work in the North Island was much slower to develop. The Maoris had no wish to sell, still less to give, their land to the settlers. They went to war and, apart from an uneasy truce in the early 1860s, the wars rumbled on in intermittent campaigns and skirmishes throughout the decade. The result was that some land was captured from the Maoris, and when the wars were over the law took most of the rest. Few Maoris could produce the paperwork to satisfy a European-style court. The way was open to settlement and railways. There was even a workforce available, the Engineer Volunteer Militia, looking for a peacetime role. Brogden again got the pick of the lines. By 1872 negotiation, a somewhat one-sided discussion with the Maoris, was over and land was acquired for expansion. Lines were built in a seemingly haphazard manner, but all pushing outward from centres of population. It began with a 44-mile route into the interior from Auckland, then one linking New Plymouth to the port of Waitara, only 11 miles long this time, but involving 1 in 40 gradients. After that the work shifted to Napier on the east coast and a major through-route to Wellington. At first work went well, but as the builders neared Wellington, they met ‘the seventy-mile bush’, an area of dense scrub and woodland, scoured by deep valleys. The difficulties met there, however, were as nothing compared with those encountered on the route from Wellington to Masterton.

The need for a railway was obvious, to provide a link between the fertile plain and the coast, but unfortunately the Rimutaka Mountains stood in the way. Experiments in the 1860s with a tramway system quite failed to meet the need, so in 1871 John Rochfort was authorized to survey this empty country to find a suitable line for a railway. He found a gorge that offered a steep climb for many miles at a more or less steady gradient of 1 in 35, but from the top of the hills there seemed no option but a zigzag, a frightening affair in terms of engineering with severe gradients, tight corners and no fewer than nineteen tunnels. The chief engineer, John Blackett, was not at all keen on the zigzag. He proposed a more direct route down the hill on a 1 in 15 grade using what he called ‘special contrivances’. Stationary engines did not seem very practical in remote areas, so he turned instead to the system pioneered in Europe, the Fell Engine (see p. 74).

The Fell system worked, but at a price: a train climbing the 2½-mile incline used as much fuel as it did on the whole of the rest of the 63-mile journey. Because the line was so steep, the engines had to be kept light, weighing in at less than 40 tons, and that had to include the extra weight for the two cylinders and associated gear that drove the ‘gripping wheels’ which held on to the central rail to give the added traction. There was also extra braking power provided by cast-iron shoes that could be used on the central rail. Even that was not enough braking power, so special Fell brake vans were imported which could also apply brakes to the central rail through a hand-wheel. The strain on couplings during the ascent was quite severe, so that a locomotive was not expected to haul more than 60 tons of passenger stock or 65 tons of freight. By the early twentieth century, trains of 260 tons were the norm, so that when they reached Cross Creek at the foot of the incline, a good deal of remarshalling had to go on. First came a locomotive, followed by a couple of coaches, then another locomotive and two or three more coaches, so that the final train would have perhaps four locomotives spread down its length and a whole string of brake vans bringing up the rear. It would then set off at a stately 6 m.p.h. up the hill. Coming down, the train could be managed by just two locomotives, but required a minimum of five brake vans. It was allowed to gallop along at a giddy 10 m.p.h. The line, opened in 1879, still stands as a striking testimonial to the efficacy of a railway in opening up the country. In an age of motor cars and jet aircraft, the tiny Fell engines hurling tall plumes of smoke into the New Zealand air as they toil up the slope, might seem comical anachronisms. But a century ago, they were the lifelines of a developing, self-confident society.