|

THE PROBLEM WITH SHOES (IS NOT JUST ABOUT SHOES OR FEET) |

Imagine you ate a diet crafted entirely out of foods available at a movie theater. Popcorn, soda, candy, and maybe a plate of fake-cheese nachos every now and then. On one hand, in terms of “getting as many calories as you need,” the movie theater diet poses no problem at all. You have food! Amazing. But unless some of that junk food was vitamin C–enhanced, you’d soon find yourself with scurvy. You’d eventually run low on B12; you’d be weak and tired and your digestion would begin to fall apart. You’d become iron-deficient, perhaps developing a swollen and sore tongue or brittle fingernails. Your diet would not include what we now recognize as good (essential) fats. Your pancreas probably couldn’t keep up with your sugar intake. Really, I could craft a list of ailments to go with each missing nutrient as well as a list of ailments that correlate with the excessive consumption of whatever is found in these foods. The list of problems with an all-junk-food diet is equal in length to the nutrients essential to our well-being. Our health is made of the inputs that we both do and don’t get.

If you asked me, “What’s the problem with an all junk-food diet?” the answer could go on forever. But in a nutshell I could say that the input isn’t what your body requires, and that without the correct input, your body will fail over time. On the other hand, given the right context—there is no other food around, for example—you could argue logically (using scientific evidence!) that the movie-theater diet is life-saving.

Similarly, conventional footwear can’t be reduced to one single problem, as each aspect of a shoe does something different to the body. Each shoe feature potentially changes the input created by moving. In some cases, the reduction of input—like a nail or a piece of glass—is welcome. In other cases, the reduction of input—like to the sensory nerves in the feet, for example—isn’t so good, especially when this reduction has been experienced over a lifetime. Tissues atrophy and die in the absence of input.

In general, conventional footwear is narrower than the foot in its unshod state, has an elevated heel, and is stiff- and thick-soled. Shoes can press the toes together, which weakens foot musculature, thereby affecting nerve health. Elevated heels make it impossible to access the full range of motion of many joints—which in turn creates highly repetitive but small motions in the hips and knees. And because all of your parts are connected, you have to make constant adjustments to the pelvis and spine in order to stay upright while you’re essentially walking downhill (your toes are below your ankles, thanks to your heeled shoes) on flat ground. Don’t get me wrong, adjusting your body to go downhill is no problem—it’s one of the reasons you come with so many hinges. But consider that you’ve been walking on some degree of decline almost every step of your life, which has forced your body to adjust not only its position but its mass distribution and pressure system—all to cope with this “heel” input. See what I mean? Shoes impact the body in many different ways.

The good news is that the very fact that there are so many different problems with shoes actually makes “getting healthier” a bit easier; you can slowly change portions of your body and your shoes over time, which keeps the transition from becoming overwhelming.

When it comes to transitioning out of traditional footwear, everyone needs to begin with a shoe variable that makes sense to their own body. As far as whole-body impact goes, I have found working to eliminate the heel the most important step. However, if you’ve got achy, grippy toes, you might want to consider ditching your clogs, mules, or flip-flops, and finding a shoe that has a more attached upper. Or maybe you’ve never worn positive-heeled shoes but still have weak feet, or ankles that pronate, and you feel like you need heavy-duty arch support in order for your feet to be comfortable. In that case you’ll benefit greatly from the strengthening and habitual positioning exercises and guidelines in Section 2—and you’ll probably need to change up the kinds of surfaces you walk on.

I’ve been teaching people about shoes, feet, and gait for over a decade, and I’ve found that understanding the basic geometry of footwear helps people understand the mechanical changes to the body that shoes and walking in shoes over a lifetime can bring about, and why and how the body adapts to different shoe input.

|

THE HEEL |

What is a heel?

A heel as I’m using the term is any elevation in the back half of a shoe. Many people claim they don’t wear heels, but unless you’ve already been purposefully seeking out completely flat footwear, chances are you’ve been wearing heels. Walk into any shoe store and look at any style of shoe, from “flats” to athletic shoes to sturdy winter boots, never mind the actual “heels,” and chances are you’ll find an elevated heel.

Truly, a heel in and of itself is no problem. The body, as I mentioned before, comes with all the equipment necessary (hinges and levers) to adjust to changing gradients underneath the feet. But what about when all of your shoes have been heeled for all of your life?

|

(AND THAT DIAGRAM THAT EVERYONE USES TO EXPLAIN THE NEED FOR MINIMAL SHOES) |

Many proponents of minimal footwear—specifically those calling for heel elimination—use a graphic similar to this one.

While a version of this image is used a lot, I don’t think the information conveyed by the image is clear to everyone—and it needs to be, if you’re trying to quantify just how much your whole body is impacted by a heel. So, lemmebreakitdownforya.

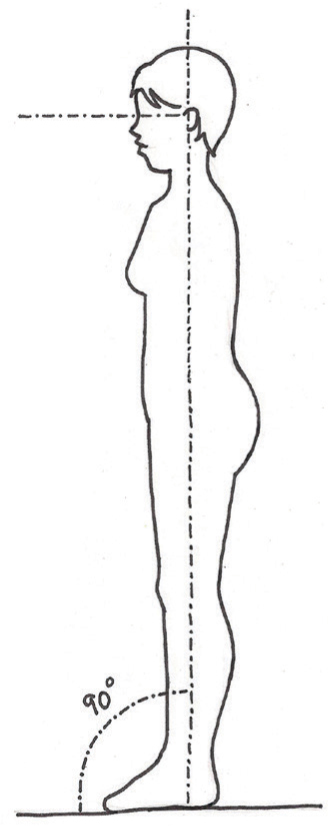

In Picture A (below) we have a barefoot person whose neutral body position lines up perpendicularly to the ground. This is helpful when it comes to figuring out loads—that is, how parts are squished between the head and the feet.

PICTURE A

PICTURE B

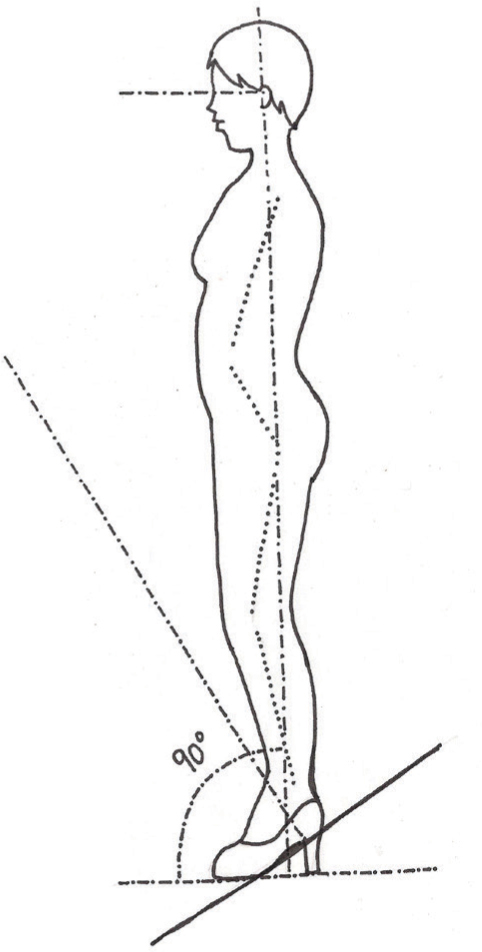

Now that the figure is wearing shoes, the “ground” (if we define ground as whatever the body is standing on) has changed, which means that the body-neutral axis is now perpendicular relative to the new ground. (Picture B, above)

Of course, the body can’t stand in this way, and THANK GOODNESS you have joints that can articulate to keep you upright when you’re going downhill. However, the body responds—continuously—to mechanical input. And what biomechanists, physical therapists, orthopedists, and YOU should be concerned with is the load created by this new surface. How does your body have to compensate for this new ground you are walking upon? What new input is created when you right yourself so that you can, in fact, walk around?

This is where Picture C comes in:

PICTURE C

In order to bring your body—your head, actually—upright, you have to move your body backward relative to your standing surface (which is the plane established by points under the ball of your foot and your heel). This picture communicates a scenario in which the shin stays forward, more in line with the shoe-ground, with the backward motion coming at the knee and ribcage—creating a particular angle in the legs and spine. This is one way of coping with shoes; the resulting shape of the body can be any combination of backward motion of the joints between the ankles and head.

KIDS AND HEELED SHOES

Recalling Picture B on page 15, there are three measures that affect how much a heel distorts a body from neutral: the height of the heel, the length of the foot, and the height of the body.

The shorter the foot wearing a heeled shoe, the greater the angle upon which the foot is set. When it comes to putting kids in heeled shoes, it bears emphasizing:

• The higher the heel, the more forward the body is projected.

• The shorter the foot, the more forward the body is projected.

• The taller the body, the more forward the body is projected.

Kids are short, but they also have short feet, which is why it drives me crazy to see a child’s shoe with a heel the same height as their parents’. The short foot of a child “magnifies” a heel’s effect—even a heel of seemingly inconsequential height. Which means that, in the case of these shoes (a woman’s size 7 and a child’s size 8.5), the angle between the standing surface and the foot would be much greater in the child than in the adult.

It also means that the necessary compensation to get the body back “upright” is relatively greater for the child than the adult. Want to experience the math for yourself? Go to a free-standing bookshelf and put any book under either the right or left side to see how far the bookshelf tips. (For extra fun, look how the books shift and imagine how the loads to each of the “book cells” change in this arrangement.) Then put that book under the back of the bookshelf and again, note the total distance traveled by the unit…and the books. Barring medical conditions or the occasional dress up, heeled shoes have no place in a child’s wardrobe. Children’s shoes are not mini versions of adult fashion; they’re maxi versions. They amplify the deleterious effects of traditional footwear. For this reason (and for many others), I buy only minimal shoes for my kids.

Picture D illustrates a different way one can “straighten up” while wearing heels. (Picture D, below)

It’s challenging for researchers to pinpoint exactly what happens when you wear a heel, because what happens depends on the shape and mass distributions of your particular body plus your preferred way to compensate. This is one of the reasons research on shoe characteristics can conflict; people are all shaped and behave uniquely, even within particular demographics.

PICTURE D

PICTURE E

|

Minimal shoes have eliminated my plantar fasciitis, which I had for a year or so. It kept getting worse, until I dropped the overbuilt shoes and started lowering my heels and going barefoot. Over a year, I went from cross trainers to Nike Frees to flat soles. Now, any shoe with a traditional heel and arch support leaves my feet aching and tired. It’s been almost six years and my plantar fasciitis has not returned. ROLAND DENZEL |

And menfolk, just because this graphic ALWAYS features women, doesn’t mean that the same thing isn’t going on in your body when you wear heeled shoes. The only difference is that the heels on men’s shoes tend not to be as high as the ones in this graphic and their feet tend to be longer (see Picture E, above). On the other hand, men tend to be four inches taller (on average) than women, which means your long body will be distorted more than a woman of lesser height wearing the same shoe size.

Here’s why this is important: Even though it seems like you’re standing upright on top of shoes, the loads to your body are very different than they would be if you were standing unshod on level ground.

When you consider, as I do, the body as a collection of cells that are individually responding to mechanical input, and how a cell’s response to its mechanical environment results in a particular genetic expression (read my book Move Your DNA for the big-picture topics of mechanotransduction and diseases of captivity), then heels become very important to the discussion.

No matter how you stack up personally, consider how each cell’s mechanical environment compares in pic A and C. Yes, a change in position requires bones to move, but it also requires muscles to shorten and lengthen. And some parts are not pressed against each other (or the ground) as much as they could have been. Cells within bones become compressed (or not), resulting in a particular bone-mass distribution. While the effects of loads are subtle, these subtle deformations are what your cells (and then, your entire body) are adapting to.

Again, stacking yourself going downhill is totally natural; what’s unnatural is the duration (all day, whole life) we’ve spent in the mechanical environment that is a heeled shoe. It’s not just that your cells are, in a shoe with a heel, behaving differently than they would in a natural scenario. It’s that they’ve behaved unnaturally almost every second of your waking and moving life.

|

THERE ARE MORE “PARTS” TO YOUR BODY THAN YOU REALIZE |

The problem isn’t only with the cellular squish. There are less subtle things going on when you have a heeled shoe, things you can see and measure with your very own eyes—like how you walk when you’re wearing them.

In the same way a shoe “casts” the loads to your cells, the heel of a shoe prevents—quite clearly—your heel from reaching the ground. So what? This constant positioning of the heel above the forefoot changes the distances over which our individual parts work. Not the whole body, of course. The whole body still moves over the ground per usual, but how that motion gets done is changed when there is a structure blocking the ankle from participating fully, the way it would if there were no shoe.

When you’re trying to troubleshoot/fix/build a machine, it helps to have a list of components or parts. If I had you name all the parts of the ankle, you could pull out your anatomy book and come up with a list that included tissue-structures like bone, muscle, tendon, and fascia. But if you’re interested in having optimally functioning feet, and restoring the motions that are necessary for muscle development, circulation, and nerve health, your list of components must include the range of motion of the ankle as a “part” of the machine. And just like you’d list all the muscles and bones necessary for facilitating full movement, so then must you list every individual degree of the ankle’s range of motion as its own part.

ONE MAN’S TRASH

Shoes bring many people relief from discomfort, and for that reason they have value. For example, one of the reasons people opt for heeled shoes is the slack a shoe’s heel puts in the posterior muscle line that runs from the pelvis to the heel of the foot. Because we’ve been sitting the bulk of our lives and worn positive-heeled shoes since just about birth, the calf muscle running from the thigh to the Achilles tendon has adapted by shortening. When you put on a heeled shoe, it gives you a little slack in the posterior-leg muscles, taking some of the pressure off your lower back when you stand up.

While the heel can bring about relief for many, the problem—the slow loss of necessary tissue mass throughout the entire body—continues. Like all “orthotics” (and I’m using orthotic as a general term to mean something that supports some systems while preventing others from working), this temporary relief ends up turning off the alarm (back, knee, or heel pain) without correcting the problem. Takeaway: Use your orthotics—whatever they may be—as necessary, but don’t mistake shutting off the alarm for putting out the fire.

It might be challenging to consider “5 degrees of range of motion” to be a real part, but keep in mind that as mobility is lost, so is the ultimate function of the machinery of the foot—of any machine, really. Would you accept wheels on your car that only rotated 355°? When you consider every degree of range of motion as “necessary,” then you can quickly see why heels don’t work for long-term function. A heel effectively casts a portion of your potential range of motion, keeping this portion from participating when you stand or walk.

Furthermore, each of the muscles we put on our imaginary list of parts isn’t really a single part at all. Each muscle-part is a structure made up of many tiny parts—parts that can be gained or lost through use. And when you lose one joint-range-of-motion part, you also lose one part of your muscle length. Walking with an elevated heel results, over time, in a loss of more parts than you were probably aware of: degrees of motion and lengths of muscle tissue.

This loss of tissue comes with a gain, but it’s not a gain that lends itself to optimal long-term function of the legs. When the heel is prevented access to the ground, all other joints participate more. Again, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing—joints are there to compensate for each other. But this particular compensation, in a natural environment, would be limited to a rise or drop in terrain that would quickly change. Our bodies’ compensations as a whole are not long-term friendly, but are best used as short-term occurrences that are constantly changing with the terrain, in the case of the foot and ankle. Only, we don’t walk on anything but flat ground for most of our steps. And the angle of our shoes is constant. Which means that our body equipment, which performs best in constantly changing conditions, has been allowed small ranges of motion at a very high frequency. And because every step you’ve ever taken has been using less of the ankle and more than what’s natural of other joints, the muscles and ranges of motion that would have been used (and strengthened) by natural walking have not been, and joints that should not have been used for every step have—and they pay the price.

OTHER WAYS CONVENTIONAL SHOES CAN SUCK (BIOMECHANICALLY SPEAKING)

• They have a too-tight toe-box that prevents toes from spreading and even crunches the toes together (think a pointy dress shoe).

• The upper doesn’t connect with the foot (clogs, flip-flops).

• The sole is stiff and unyielding, forcing the work of walking to come from the ankle rather than being distributed throughout the foot, and also thick, so that the foot isn’t distorted (read: moved at many of its thirty-three joints) by walking over shapes provided by the ground.

The effects of this loss/gain relationship don’t just apply to the foot and ankle; the effects are whole-body. Once you start compensating, other joints become limited by proxy, other muscles’ lengths are lost, and so on. And it’s not all loss and shortening; the opposite is true for the opposing areas—imagine the front of the shin of a habitual heel-wearer. When a joint angle is held open for a longer duration than is natural, tissues have to change to accommodate this load. In many cases this brings about unnatural increases in joint laxity (commonly referred to as hypermobility) and in muscle length, which also limit ranges of strong and stabilized motion in a slightly different way.

|

My wife started wearing Vibram Five Fingers and I did my share of making fun of her goofy-looking shoes. She had some foot problems before, but after six months or so in barefoot shoes, her problems were all gone. As a runner, I held the mindset that my foot needed a raised heel, padding, and arch support to perform at its best. But after seeing her feet, knees, and back get so much better wearing minimal footwear, I gave barefoot shoes a try. Now, all my athletic pursuits are done in minimalist shoes. I feel more grounded and more connected. JEFF HEMMAT |

|

After following Katy, I realized how damaging all those years (multiple decades) of wearing flip-flops were. I have been stretching out my calves and toes and that has transformed the way I walk. As an added bonus, my horseback riding has improved immensely because I am no longer clenching my toes! DIANNE MCCLEERY |

Are there good heels and bad heels? No. There are just heels, no judgment. But every positive heel—even those that have been deemed “sensible”—impedes your body’s full range of motion and affects the literal shape of your body. Which means that even if you work hard to live a movement-filled life of walking, squatting, and hanging (all the essential movements I recommend in Move Your DNA), if you do so wearing conventional running shoes with a half- to one-inch heel, you’re not bringing all of your parts to the party.

|

TRANSITIONING OUT OF A HEEL |

So you want to invite some of your old parts back to the party. Does that mean you should throw out your heels straight away? Nope. When you’ve worn a positive-heeled shoe the bulk of your life, your tiny parts are distributed differently than you need them to be in order to walk with your heels down. To transition abruptly is to run the risk of creating an injury. My first recommendation for moving away from a heel is to spend at least a month doing the correctives (exercises and habit modifications, found in Section 2) daily while continuing to wear your regular shoes. Yes, even if you regularly wear high heels. ESPECIALLY if you wear heels every day, all day long. Focus on gradual changes in your shoes. Start working your (heel’s) way down, but do it in stages. There are a number of “transitional” minimal shoes on the market now that offer an 8 millimeter or 4 millimeter heel rise. Slowly lowering the height of your shoes’ heels while at the same time following the exercises laid out in this book is your best bet.

IT’S NOT ONLY THE SHOES

It’s important to note that the tension in the calf—tension that results in heel pain for many—doesn’t only stem from how your shoes fix your ankle into a slight toe point, but also from how a chair “casts” your knee at 90°. Which means that if a minimal-shoe-friendly body is what you’re after, you should also reduce the amount of time you spend with your knees bent—a position that also shortens the posterior leg muscles. You’ll find more on this as well as exercises to help in Section 2.

You’ll know you’re ready to progress to a lower heel height when you are able to go deeper with the calf stretch series, when it’s easy for you to keep your pelvis from jutting forward, and when you can walk in lower-heeled shoes without pain.

|

THE FLIP-FLOP FLAW |

Maybe you’re a flip-flop lover feeling pretty relieved because your flip-flops seem minimal—flat, wide, and flexible. They’re also “open”—an important component of the “natural” argument, as they allow for greater sensory input in the form of air pressure and temperature. It’s true, flip-flops are SO CLOSE! But flip-flops fall short of being minimal-for-the-purpose-of-natural-gait in a vital way—they don’t connect to our feet. We have to work our muscles unnaturally to keep them on. (Unfortunately, this toe-gripping action is necessary for slides, mules, and many slippers, too.) After a while, the toe-gripping motor pattern leads to shortened toe muscles (and a loss of parts that allow movement) which can then affect things like balance and foot arch strength, and lead to toe contractures, a.k.a. hammertoes. New flip-flop research also shows that “working to keep the shoe on” changes many things about your gait, which means they end up affecting more than the feet.

I know, I know. Gripping doesn’t sound like such a big deal, but gripping—when you’re walking—is more than just toes bending in different places. Those bends end up changing which parts of the foot push into the ground. Those bends end up translating into mechanical input at the level of the nerves and skin and can create many problems not filed under “musculoskeletal.”

Let me show you.

When you wear shoes that don’t hold themselves on your foot, this is how the grip translates into buckling parts and pressures:

The “grip” to keep footwear on curls some toe bones up and some down, drives the end of some bones into the ground, creating higher-than-normal pressure (which is what can lead to toe contracture/metatarsal injury over time), and drives the ends of some bones up into the top of the shoe (which can lead to corns and calluses over time if there’s something for the toes to rub on overtop). I won’t even mention the tension down the front of the leg—because you’ll find it yourself during the Top of the Foot stretch in the exercise section. (If you want to try that right now, go ahead. I’ll wait.)

To keep your natural stride (and shoe) on and enjoy the feel of the sea breeze and sunshine on your skin, or the grit of dirt and the freezing cold air of a Canadian fall, opt for something that looks more like a Greek sandal. You know, all strappy and minimal but still fully connected to your foot. If you look around, you can find uppers that are very minimal as far as mass goes, but engineered in a way that keeps the shoe on without you needing to tighten your toes.

|

ANKLE SCHMEAR |

I’ve talked about some of the instant distortions that shoes can bring about. There is also longer-term physical distortion brought about by muscle strengths and weaknesses, in turn brought about by the distances you have walked (or haven’t), how frequently you have sat (and how), and your shoe history over a lifetime.

You and I are part of a fully shod, sitting-most-of-the-time culture, and the effects go beyond tight hamstrings and calves, or bunions and hammertoes. Just like the flopped-over fin of an orca in captivity, our legs as a whole are collapsing at the hip—and taking the ankle with them. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: foot health is a whole-body issue, and perhaps nothing demonstrates this as clearly as ankle schmear.

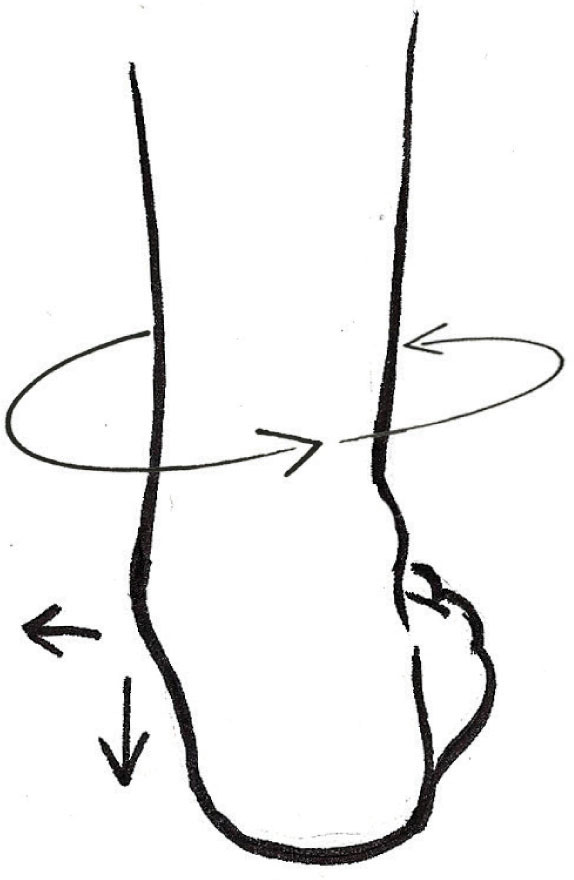

Ankle schmear is a term I coined myself, because I find it helps clarify what’s actually going on structurally during a motion called pronation. You’ve probably heard of pronation—the “inward” roll of the foot while you’re walking or running. Many an athletic shoe and orthotic has been devised to prevent this from happening and it’s usually drawn like this:

But pronation isn’t really a tipping-inward motion—or more accurately, it isn’t only a tipping-inward motion. Pronation is actually a tri-planar motion of the ankle complex, meaning that the bones in the lower leg and foot move and change orientation in three different planes, meaning we need to talk about planes now.

PLANE 1: Say you’re going to spread some peanut butter onto a piece of bread and you start with the peanut butter on one side of the slice and move it to the other side.

PLANE 2: When you spread the peanut butter from right to left, you’re not only moving it across the bread, you’re decreasing the height of the original pile as well.

PLANE 3: Okay, so now pretend the knife’s handle has been anchored at one end with a nail. In this case you would not be able to spread stuff from right to left, but would be forced to spread the peanut butter from one side of the bread to the back edge of the bread by swinging the knife around the axis created by the nail:

Voila! If you put those three motions together, you get pronation: a motion that rotates the shin inward (think knees pointing more towards each other), moves the leg toward the midline of the body, and lowers the leg a bit closer to the floor.

So now let’s talk about schmear. While I do like to make up words (thank goodness for book editors), I didn’t create the term ankle schmear just because I didn’t like the term pronation. Schmear and pronation are different, and here’s how: Pronation is the tri-planar movement I’ve described above and schmear is the effect of this triplanar distortion on the lower leg as a whole. You see, the foot and all its motions do not exist in a vacuum. (P.S. If you’re currently living in an actual vacuum that last sentence doesn’t pertain to you.) The sole of your foot is in a physical relationship with the ground below it.

|

I don’t remember when I first was told I had flat feet, so I guess I assumed I was born with them. Progressively thicker and “more supportive” orthotics for my unusually flat feet did little to help my foot pain…or the knee, hip, and back pain I developed. When I developed horrible plantar fasciitis, enough was enough, and I went on a quest to fix my feet. Lo and behold, it was all schmear! The post and video about foot schmear changed my feet and my life! I threw out my “supportive” footwear and started retraining and rehabilitating my poor feet (and legs). Fixing the foundation led to less knee and hip pain, and also a healthy obsession with alignment! AMANDA JOHNSON |

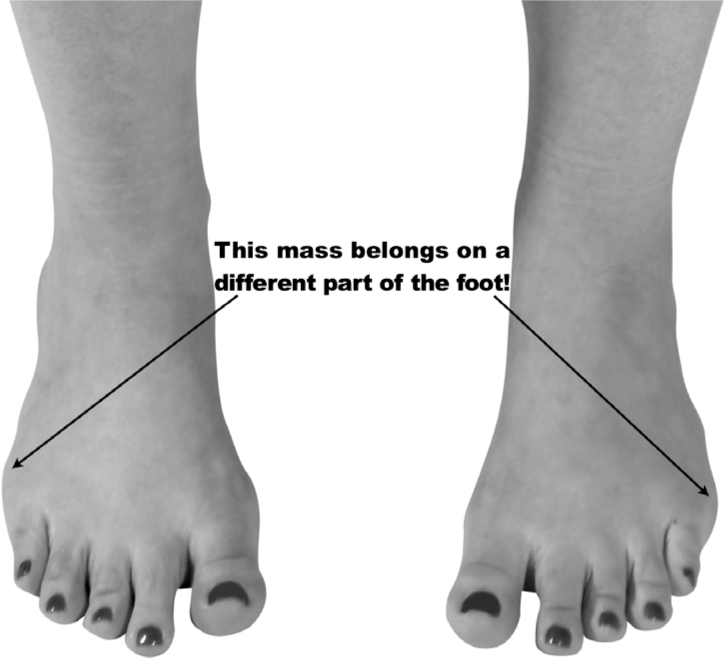

Because your foot skin is in traction between the ground below and the body above, when the leg rotates inward, the shin brings the top of the foot with it, pulling the top of the foot away from the bottom, which creates “extra mass” on the outer edge of the foot. With schmear, what you get is all parts of the foot distorted, both relative to the ground and to each other. (see image.)

Understanding schmear will come in handy when you start lining up your feet only to find that you’ve got a bulk of mass extending beyond the outer edges of the foot. Yes, in many cases, when you look down at the top of your foot, you’re staring at a portion of the bottom. Wait. What did you say? What just happened? Go back and read it again.

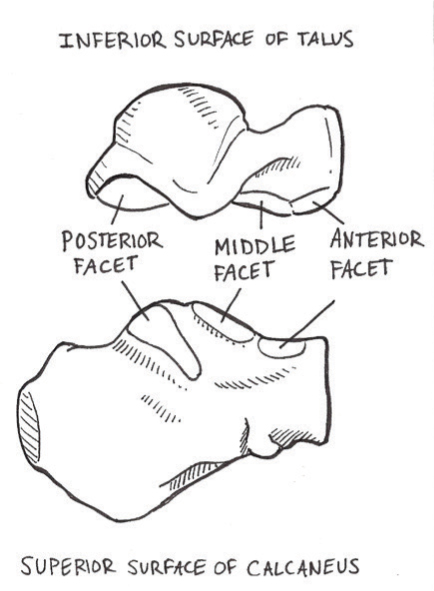

THE ANKLE JOINT COMPLEX

Most people think of the ankle joint as an up-and-down hinge, moving at those two quarter-sized bumps (called malleoli) just above your foot, but if we go a bit deeper we find movement in the “ankle” area to be more complex, hence the term ankle joint complex.

What we normally think of as the ankle is actually two joints: the talocrural (superiorly—closer to the head) and the subtalar joint (inferiorly—closer to the feet). Just looking at the two names, you see that both joints share the talus bone (Latin, for ankle). The “true” ankle, or talocrural joint, is made up of articulations between the tibia, fibula and talus. The subtalar joint (aka the talocalcaneal joint) is made up of an anterior, middle and posterior facet, and is what allows for the triplanar motion.

The “true” ankle joint brings about (dorsiflexion and plantarflexion) motion at the malleoli, but the subtalar joint below acts more like a gyroscope, allowing the body to walk upright even when walking over varied terrain.

Because our walking is primarily flat-and-level-ground walking, the dynamic function of the subtalar joint is less than what it would have been were we walking on varied terrain, and following suit, exploration into the universal function of the ankle joint complex is less than what it should be. Meaning, research into the ankle complex has been skewed towards research into the “function of the ankle” as it functions on flat and level ground.

Isn’t biomechanics fun?

So now you know that the bones of your feet can move within the foot-skin casing (thank goodness for the fascial system!), which may have you asking, “So what muscle can move my sole back under my foot?” And the answer is…there is no muscle in the foot that can get your foot-parts back to where they should be. Rather, the foot skin has to be unschmeared by the reverse motion of the hip (external instead of internal rotation) while the foot skin is on the ground. Sole + traction + external rotation can change the foot skin, the loads to the foot bones, and the axis of the ankle joints in one fell swoop. Which is why I include this and other exercises to strengthen the hip rotators and lateral hip muscles in Section 2.

MEASURING PRONATION CAN BE SLOPPY

Because the width of our feet and pelves (the plural of pelvis, which is pronounced PEL-vees and not a single-syllabled pelvz, which would be the little creatures that live in your pelvis and make cookies) are unique to each of us, the amount of displacement in each plane varies. If your pronation were measured via a simple data collection (i.e., considering only the inward displacement measure featured on page 28), but you had more rotation than you did translation, you might miss that your entire lower-body structure is operating off some of its axes. (Axes is the plural form of axis and is pronounced AX-ees.)

When you start working on changing your thigh position, as you’ll find in the thigh-rotation exercise, there is an immediate change to the position of the hip, knee, ankle, and—because you’re unschmearing—the height of the arch of the foot. And with foot-arch height can come a reduction in foot length.

|

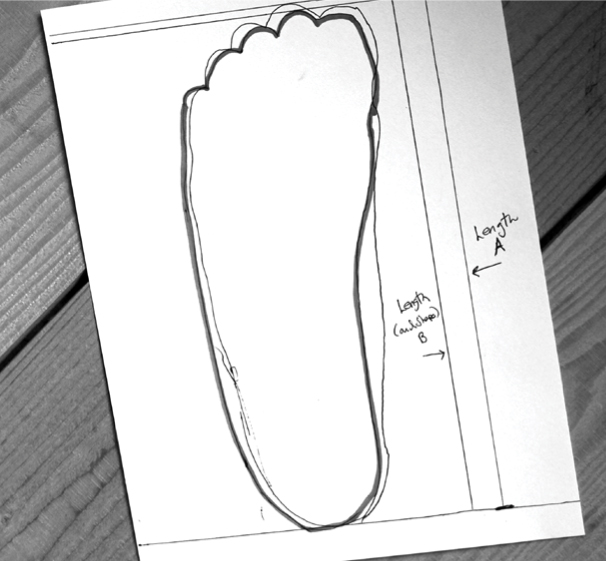

LET’S CHECK IF YOUR SCHMEAR IS AFFECTING YOUR SHOE SIZE |

1. Stand on a piece of paper with your foot pointing straight forward, completely loaded. Keep your muscles relaxed. No need to correct anything yet (we want to see where your foot is most of the time).

2. Trace around your foot.

3. Step off and measure your foot length.

4. Place your foot back into your print and then externally rotate your thigh until your knee pit is in neutral (as described and pictured in Neutral Femurs on page 50).

5. Retrace your foot.

6. Highlight your “rotated thigh” foot with a different color and re-measure your length (or width or just shape in general). Here you can see that not only is my left foot (which always runs about quarter-inch longer than my right) shorter when my thigh and shin are less rotated off their axis, it is also narrower once I’ve undone the tri-planar distortion of my ankle complex.

1

2

3

5

6

Try both of your feet and see how they compare. For example, my left “tricky hip” is chronically more internally rotated than my right when I’m not correcting it. The result is a longer, wider foot on the left. My left foot is more schmeared.

Speaking of shape, take a look at the stuff underneath your feet right now. I’ll bet that over ninety percent of you are looking at flat and level ground. In fact, if you tallied up what’s been under your feet your whole life, you’d find that most of it has been flat and level. Which means the parts of your body—the articulations and the muscle mass used via those articulations—that aren’t required on flat and level surfaces have been lost. (And, P.S., flat and level would occur almost never in a natural environment, so not only do we have a particular foot and ankle shape created through this narrow, repetitive use, it’s a strange shape at that.)

I’m hoping that by now you understand why the allopathic view of minimal shoes (“They cause injury!”) is not entirely accurate, but also not without merit. And that the all-barefoot/minimal view (“It’s natural!”) is missing a key piece: your feet are not “natural” any longer, and neither is the stuff you walk on.

|

I come from a family of bunion-makers. They all wear orthotics as well. By age twenty I also was the proud owner of my own orthotics, and debilitating back pain. By thirty I realized this just wasn’t working. I ditched the orthotics, started going barefoot, started stretching my feet. By thirty-five I was doing lots of yoga and wearing the most flexible shoes I could find, by forty-four I found you online, and realized “I’m on the right track.” Here I am at forty-eight, cruising through the first level of your course, learning even more, getting stronger, and I have no bunions! ALIX RODRIGUES |

I once attended a lecture on barefoot living that was impressive in its inclusion of beautiful foot anatomy and force diagrams and explanations of how things work in the foot. I loved it. And I agreed entirely that being barefoot is necessary for optimal, whole-body function. But while the lecture was spot-on with the intra-foot physics, the forces listed for the foot did not include any outside of the foot. It was a “here’s how the foot works” talk without any consideration given to the fact that the foot does not work in isolation. If you’re going to use a biomechanics argument to support your recommendations, you have to use all of the mechanics—and include forces created by stepping with the foot.

DOCTOR’S NOTE

“As a podiatrist I’m constantly working with people to resolve or reduce the pain in their feet, but what I spend quite a bit of time doing in each appointment is illustrating how their foot position—and pressure on their “sore spots”—is directly impacted by the position of their thigh bones.

Chronic internal rotation of the hip is a pronation creator. By learning more about the location of a neutral knee pit and working towards decreasing internal rotation, you can remove much of the pronation collapse. As for me, what I can do is put you into orthotics, designed to increase the position of the arch and control pronation, to change the loads. But this doesn’t do too much for the problem of weakness in the hip and foot. I tell my patients they’re going to have to do some work (via exercises and awareness) on their end for long-term success.”

—Theresa Perales, DPM

|

Three pregnancies on already-flat feet had my toes pointing in different directions. Eighteen months in minimal shoes and my feet are strong and have arches and nicely spaced, straight toes. (And they’re warm.) ABBY MILLER |

|

SO, WHAT’S NATURAL? |

Think of the roots, rocks, mossy patches, and inclines of a forest floor. To walk (minimally shod or barefoot) across that surface requires literally countless joint angles and configurations as your feet adjust to each unique surface. The more inclines and declines on a walking surface, the more variation in ankle, knee, and hip use, pelvic positioning, and the greater variance in muscles used throughout the entire body. The more natural debris—twigs, leaves, mushrooms, stones—cluttering the surface, the more your whole-body musculature has to work. And, in both cases, the more of your “parts” you keep.

Now think of the sidewalks, roads, and indoor floors and walking tracks that your feet have spent a lifetime on. See the difference? Even if you’ve done a lot of walking in your lifetime, chances are most of it’s been on unnaturally flat and level surfaces. And the hardness of concrete, while somewhat similar to the firmly packed dirt of a trail, still exceeds the natural biological forces created by the interface of natural on natural. The increase in impact, made worse by poor walking or running mechanics, can increase the risk of injuries like fractures.

One of the reasons I’m not barefoot all of the time is because I can’t do it naturally. Shoes, one could argue, serve a role in buffering our bodies from a repetitive-use injury that could be made by the unnatural loads between the body and man-made ground, both in the case of its hardness and its flatness.

The body is tough and can handle the impact of walking on hard surfaces, but the repetition of doing so can cause injury, as every single step is an unnaturally high load. Can you just bend your knees to soften the blow to your feet? Sure you can. That’s why you have knees. But now you’re compensating for the unnatural loads to the feet by creating unnatural loads to the knees.

By now you know it’s not just your feet. Your hips’ weakness, caused (in part) by the repetitive flatness of manmade surfaces (e.g. the lack of incline or decline) as well as your lack of walking in general, has resulted in your entire legs being off their axes. Which means your foot bones, soles of the feet, ankles, knees, and hips are oriented in a position that makes for wonky loads with every step.

So should I get rid of my shoes? Without getting rid of the habits (adaptations to shoes, sitting, little walking, walking on unnatural surfaces) that themselves create issues in my feet, I’m not so sure that’s a good plan.

By walking on such artificial surfaces all of our lives, our amazing, strong, variable musculature has adapted, becoming very good at walking on one kind of ground. That sounds great, right? Adaptation is a good thing! In fact, adaptation isn’t good or bad; adaptation is just adaptation. We have this idea that the body can endlessly adapt to whatever we choose to do, but that’s not the case. We can adapt for a while, but there is always a biological tax. And in many cases, this tax is so far removed from the initial point of compensation, we don’t even associate the two, which keeps us consuming the problematic load.

|

YOUR MISSION: MOBILIZE YOUR FEET, IN THE LAB AND ON THE FIELD |

Many therapeutic modalities include joint stability exercises in the attempt to strengthen the ankles for handling detritus, walks over sand and stones, and rooty forest floors. But these exercises are typically done for just a few minutes a day—the rest of the time the client consumes the same mechanical environment—flat and level ground—while wearing shoes that prevent the parts within the foot from participating. Corrective exercises as a sole means to consume the “nutritious loads” necessary for whole-body function require off-roading. While flat-ground walking is a great way to get some of you in shape, not all of you is getting healthier for the effort. So, like supplementing your diet with vitamin B12, you’re going to have to supplement your walking with actual over-ground walking. You’re going to have to start walking—on the actual ground, in as many forms as you can find.

GENERAL GUIDELINES FOR FOOTWEAR TRANSITION

When switching to barefoot or minimal footwear, give underutilized muscle time to develop. Begin foot exercises before switching shoes, and continue the foot exercises while doing your whole-body training in less supportive shoes.

Master shoeless walking before you try shoeless running. Running creates greater forces in the joints of the foot, so walking is the more natural precursor to developing the appropriate strength for running. Before you run five or eight miles in minimal shoes, make sure you’ve walked five or eight continuous, well-paced miles in them first.

Once you’re ready for running, start with short distances first—on dirt or grass—before logging longer runs.

Seek out expert guidance on running form. Conventional running shoes offer excessive cushioning to protect against high joint forces. The better you align your feet (and your body above your feet) while exercising, the less you will overload them.

A huge part of transitioning to minimal footwear is working to un-adapt our feet (and the rest of our bodies) away from the artificial environments to which they’ve been exposed. Your strong around-town feet aren’t necessarily suited for all-terrain walking, and in order to reap the benefits of the dips and hills and lumps and bumps found in nature, your feet have to be supple enough to allow these movements. Mobilizing exercises might seem very passive, but they can be the most difficult, because our feet have been in casts for most of our lives and getting them to move can be a bit painful. I’ll help you break down the loads to keep the stress on your feet gradual and your foot-restoration program rolling along.

By this point, you know that the health of your feet isn’t dependent on your feet alone. Your feet are affected by what your whole body is doing (and vice versa), including what you put on your feet. A whole-body problem demands whole-body solutions. The good news is, when you turn this page you’ll find your new to-do list waiting for you. Have fun!

|

Throwing out my heels was hard at first, until I started seeing the results. I had been suffering with low back and pelvis pain that kept me basically disabled for three years. After lots of PT and chiropractic work, my neurologist had told me I would fight some chronic back pain the rest of my life because at twenty-seven, I had a sixty-year-old back. I didn’t think I wore a lot of heeled or problematic shoes, until I learned from Katy how I was perpetuating my own pain in my footwear choice. The results were so compelling and (relatively) quick that I was a hundred percent converted within a year, giving away every sentimental pair of “cute” shoes. In the three years since then I’ve seen my bunions heal by fifty percent on the bad foot, and almost completely on the other. The women in my family, who also have “genetic” bunions, as well as a hereditary love of cute shoes, have noticed. In particular, my mom has started her transition this last year and dramatically improved her prolapse. MARCEE MONROE LUDLOW |