Composition, or What Goes Where

UNDERSTANDING COMPOSITION—the conscious placement of elements in a picture—will help you get better photographs. The principles of composition—especially getting closer to your subject, the Rule of Thirds, and orientation—give any photographer an express route to picture-taking success. The beautiful thing about these principles is that you can make use of them with any digital camera, whether a sophisticated SLR or a fits-in-your-shirt-pocket point-and-shoot. Best of all, practicing good composition is just plain fun.

Working with a 2x teleconverter disables the autofocus and increases the challenge of getting a tack-sharp photo. I had my lens mounted securely on my tripod and made seven exposures to get this one keeper. The key to its success is its up-close-and-personal composition.

1/180 SEC. AT f/11, ISO 800, 100–400MM LENS WITH 2X TELECONVERTER AT 800MM (THE 35MM EQUIVALENT OF A 1280MM LENS)

THE LIBERATING THING about understanding composition is that you decide what to include in the photo, where to place it, and how much of the picture the subject occupies. Just as important, you decide what to exclude from the photo. You dictate how your subject relates to the foreground (whatever is in front of the subject) and the background (whatever is behind it).

By simply changing your point of view or position, you can capture a completely different image. By moving a little to the left or right, a little up or down, you can cause the various elements in the scene to work with (or against) one another in unique and sometimes surprising ways. The choice is up to you: You can accept the world as it is presented to you, or you can move around and experiment with various views, exploring how each change can dramatically alter your photo.

Before you begin to arrange the various elements in your photo, however, you need to determine what you’re trying to shoot. This is often more difficult than it sounds. It may be easy when you’re making a portrait of your family or your cat, but it can be extremely challenging when shooting other subjects. For example, when photographing a landscape or travel destination, you need to consciously ask yourself, What exactly is attracting my attention in this particular scene?

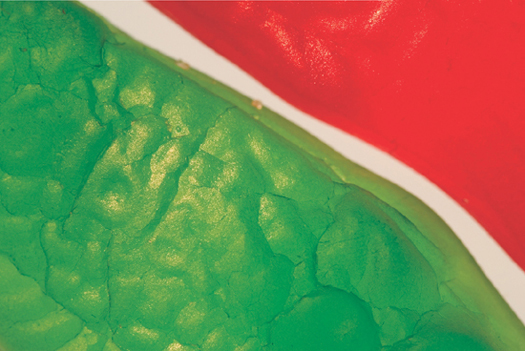

These three examples illustrate a situation in which you can rearrange your subject (as opposed to repositioning yourself) to get the composition you want. The first photo is displeasing because it has no order. However, the second photo is too orderly, too “staged” The third photo is also staged, but because the composition is simple, it is much more pleasing to the eye.

ALL PHOTOS: 1/125 SEC. AT f/11, ISO 100, 100MM MACRO LENS

This thought process is challenging because the decision involves making sacrifices. As much as you might wish to include everything in the picture, selecting one main subject and letting go of the other elements in the scene will help you make a better composition. Most photographers avoid making this decision and just hope the picture will turn out; they step back, take a photo of the entire scene before them, and later wonder why their pictures are so boring.

After deciding on your subject, dig even deeper, asking yourself questions like, What would I like to do with my subject? and, What effect would I like to have on my viewer? This is where the real art of photography comes in. Once you’ve chiseled out your vision, you can then use the principles of composition, as well as other guidelines presented in this book, to create the effect that you’re after. Making this kind of conscious expression may sound challenging, but believe me, with a little help and a little reliance on the guidelines, you can do it!

When photographing this subject, I sensed that I wasn’t successfully capturing the image I had in mind. At first, I couldn’t determine what exactly the problem was. So, I did what I often do when faced with such difficulty—I exchanged the normal zoom lens on my digital SLR camera for a 100mm macro lens and moved in superclose. Honing in on this one detail of the horse and saddle brought me much more satisfaction than trying to capture the entire subject.

TOP: 1/350 SEC. AT f/6.7, ISO 100, 100–400MM LENS AT 160MM; BOTTOM: 1/250 SEC. AT f/4.5, ISO 200, 100MM MACRO LENS

COMPOSITION is all about organization and simplification. Every element in your photo has a place. If it doesn’t have a place, it needs to be eliminated. The easiest way to eliminate extraneous elements is to move in closer toward your subject. In fact, nine times out of ten, once you know what your subject is, all you need to do is simply move in closer to it. If your subject doesn’t completely fill the frame in your viewfinder, the picture will likely include details that can distract the viewer’s attention.

Twigs, telephone wires, pieces of trash, camera straps, you name it … anything competing with your subject for attention should be eliminated. Filling the frame with your subject is a surefire way to get rid of this visual competition.

Even if there are no distracting things along the edges of your composition, the blank space around your subject can pose a similar problem. Too much negative space around your subject tends to lessen the picture’s impact. You want your subject to be right in your face, up close and personal, so it can’t possibly be missed.

This isn’t to say that you can never again use the wide-angle option on your lens. Just make sure that when you do shoot wide-angle, the entire scene plays an active role in your image. Every element in the composition, whether it plays the “starring role” or helps out as “best supporting” element, needs to be absolutely necessary and required. If it isn’t, cut it out.

ADD AN ELEMENT OF INTEREST TO LANDSCAPES

When you want to capture a large expanse of a beautiful landscape, it often helps to have a good point of interest. A foreground rock, bed of wildflowers, old rusty piece of farm equipment, or a little red car can give the eye something to focus on and add a sense of depth and scale.

1/350 SEC AT f/10 ISO 400 16–35MM LENS AT 16MM

For the initial wide-angle image, I wanted to show the coyote in its environment. My subject-was-the relationship between coyote-land, and sky. The photo works, but it would be more engaging if the coyote were looking to the left, back into the scene. A few minutes later, the coyote moved extremely close to me. Fortunately, I still had my 16–35mm lens on the camera and was able to get the close-up wide-angle image opposite. While both photos are good, the second one does a better job of capturing the character of the coyote.

1/500 SEC. AT f/11, ISO 400, 16-35MM LENS AT 34MM

Anyone using a camera with a zoom lens–whether it’s a digital SLR or a compact digicam—can quickly change composition by simply zooming in or zooming out. Zoom in for a tighter composition and zoom out for a more expansive, wide-angle view. A focal length of 16mm to 35mm is considered wide, and a focal length of 110mm to 300mm or more is considered telephoto.

Telephoto and Wide-Angle Lens Attachments

As soon as photographers with compact, fixed lens digital cameras experience the limitations of their zoom lens, they want a way to either get closer to their subject or create a wide-angle image. Some manufacturers have responded to this by offering lens accessories, such as screw-on or clip-on lenses to change focal length. In my experience, these lenses often result in a noticeable reduction of clarity, accuracy, and quality. If you’re considering purchasing these add-on attachments, you might want to consider saving up for a digital SLR camera instead. Actually, the cost of a compact digicam with an add-on lens attachment could easily exceed the cost of a digital SLR. You might actually save money going with a digital SLR! (See the Digital Camera Buyer’s Guide.)

While photographing landscapes one day, I learned of a nearby falconry. My schedule didn’t allow me to stay for a falconry demonstration, but I was still able to spend some time getting very close to a variety of birds. This tight head-shot of a Bateleur eagle successfully conveys the intensity of the subject and also utilizes the Rule of Thirds.

1/180 SEC. AT f/11, ISO 200, 2X TELECONVERTER AND 100–400MM LENS AT 400MM

(THE EQUIVALENT OF A 1280MM LENS ON A 35MM CAMERA)

Here’s another example of how working your subject—shooting in a variety of ways—can pay off. For the initial photo above, I placed the petal on a light box and composed in a way that included the petal’s reflection. Then, I gradually moved in closer, making a variety of exposures in the process. By the time I made the final image I was quite close to the petal. I positioned the camera so that the focal plane was parallel to the petal. I did this to get as much in focus as possible, considering the narrow depth of field inherit in macro photography. Additionally, I wanted the one strong red line to travel diagonally through the frame, adding a sense of vitality to the abstract composition.

1/2 SEC. AT f/32, ISO 100, 100MM MACRO LENS

Keep It Simple

Regardless of subject size, however, the idea here is that you Want your composition to be clear, simple, and easy for the eye to understand. Simplicity is one of the most powerful things to keep in mind when composing your photographs. Be brutal! Like the Terminator, you want to scan your scene—looking for any distraction—before pressing down the shutter button. Then, you want to take steps to annihilate anything that doesn’t belong in the picture.

1/3 SEC. AT f/11, ISO 100, 100MM MACRO LENS

YOU MAY HAVE HEARD Robert Capa’s famous quote “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” What most people don’t know is that just after uttering these immortal words, Bob’s eyes glazed over and he prophetically added, “But, whatever you do, don’t use your digital zoom.” (That’s a joke, of course. Robert Capa died long before digital cameras became popular.)

Like countless photography instructors, I used to think that the digital zoom always resulted in low-quality images. I would tell students, Whatever you do, don’t use the digital zoom feature of your camera. I advised them to rely on the optical zoom, as this produced images with higher resolution and quality. Getting myself all worked up, I would call the digital zoom a marketing gimmick, whose sole purpose was to trick novice photographers into forking over their hard-earned dollars on a new digital camera.

But then I tried it out for myself, comparing digitally zoomed images with those enlarged in Photoshop. I humbly admit that I found the digitally zoomed versions better looking than those enlarged in Photoshop.

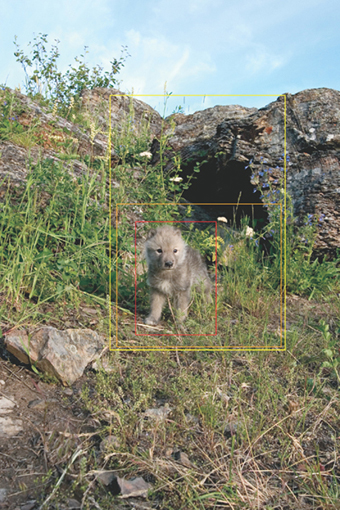

OPTICAL ZOOM

DIGITAL ZOOM

OPTICAL ZOOM ENLARGED IN PHOTOSHOP

The first image was shot at the maximum optical zoom setting. The close-up is at the maximum digital zoom. Although it is a bit pixellated (meaning you can see the individual pixels, or bits of information that make up the image), this digital zoom example is not as bad as I would have expected. I actually find it more pleasing than the version it that I enlarged in Photoshop. The lower quality of that image is most likely due to the fact that I photographed the optically zoomed original as a JPEG. When enlarged, the artifacts from JPEGs become more visible. If you shoot in TIFF or raw format and don’t mind cropping images in a software program, you might be happiest sticking with the optical zoom. In any other case, don’t refrain from using the digital zoom. Just be sure to (a) use your tripod and (b) closely examine your first results to see if they are of an acceptable quality to you.

Digital SLR Cameras with Interchangeable Lenses

If you shoot with a digital SLR that features interchangeable lenses, you have additional options for further manipulating your composition. As long as your pocketbook can bear it, you can buy and use a wide variety of zoom or fixed lenses—everything from super-telephoto lenses to special macro lenses. Each lens costs a fair amount of money, though. Before you take the plunge into the wonderful world of digital SLR photography, understand that lenses can cost more than the price of the camera body, and digital SLR photography will likely lead to a substantial investment in the future. I still recommend it; just prepare yourself for the potential costs.

There still are a few things to keep in mind when using the digital zoom feature. First, placing your camera securely on a tripod will greatly improve your ability to capture satisfying images. If you don’t, your camera will jiggle as you take the picture, and this movement (camera shake) will result in blurry pictures. Second, cameras with lower pixel resolutions will likely perform poorly in the digital zoom department. These digital cameras have been known to behave in one of two ways and both ways have disadvantages: If the camera is designed to crop in and reduce the resolution of your image, you’ll find that the zoomed image doesn’t print as big as optically zoomed images; or, if the camera tries to fit the smaller, zoomed-in view to its original pixel resolution (without cropping and reducing resolution), you’ll find that the artificially enlarged image doesn’t produce high-quality prints.

Having said all this, there is a useful purpose for the digital zoom feature. It can be helpful if you don’t feel comfortable cropping pictures in computer software. Photographers who take their memory cards to a photo lab to have their images printed directly on a kiosk printer will appreciate that the images they have digitally zoomed in camera are ready to go. Although you can crop an image before printing on a kiosk, many will still find the digital zoom method easier than cropping on a kiosk or computer.

While you’re still learning, the best practice is to take one of each—one photo with the optical zoom and one with the digital zoom. Although digital zooming technology has progressed significantly, many may still find that they prefer the quality of an optical zoom. My advice is to try out the digital zoom and, if you like it, use it with a tripod, taking backup optically zoomed photos whenever possible.

If you can’t optically zoom in closer, first try moving closer to your subject. If your subject is an animal, it may bolt (or attack—so be careful) if you get within its flight range. If this or any other considerations keep you from getting physically closer, place your camera on a tripod and use the digital zoom. Shoot both optical- and digitalzoom versions. This way, again, you’ll have a backup that you can crop in the computer if the digitally zoomed version is unacceptable. Give yourself more choices rather than less. If you shoot the entire scene first, you’ll have the option of cropping the photo in a slightly different way in your software at a later time.

Cropping in Camera or on the Computer

You have three choices when it comes to removing extraneous details surrounding your subject:

1 You can physically move in closer at the time of shooting.

2 You can use the optical or digital zooming features of your lens. These first two options are called cropping in camera.

3 You can crop after the fact, using software, but this takes time and a certain willingness to learn these software techniques. More importantly, it reduces the file size of your image. Unless you’re only e-mailing or displaying your photo on the Web, your photos may suffer; i.e., you won’t be able to print them as big without seeing a noticeable reduction in quality.

Even Bigger Birds and Bees: SLR Magnification Factor

When teaching 35mm film photography, I used to tell photographers interested in making images of birds that a 300mm telephoto lens just wouldn’t cut the mustard. Those photographers just could not get close enough to such small subjects with that lens. If you use a digital SLR, this may no longer need to be the case. Standard 35mm lenses, when used on most digital SLR cameras, are magnified by a factor of 1.3 to 1.6. What would be a 300mm lens on a film camera instantly becomes a super-telephoto, with over 500mm of magnifying power, when placed on most digital SLRs.

For those interested in moving close to distant subjects, this kind of lens power can come in very handy. It’s a great feature for those who like to photograph wildlife and other subjects that generally don’t like it when you get too close. This can also help out a lot when shooting shy subjects, such as when you’re trying to capture candid photos of your children, spouse, or friends.

When photographing this golden eagle, I set my 100–400mm lens to its maximum focal length (400mm). I then doubled this length with the addition of a 2x teleconverter. What’s more, because I was using a digital SLR camera with a 1.6 magnification factor, this 800mm focal length would be more comparable to a 1280mm lens on a standard 35mm film camera. Talk about getting close to your subject! I love this advantage of shooting with a digital SLR.

1/180 SEC. AT f/11, ISO 100, 2X TELECONVERTER AND 100–400MM LENS AT 400MM

(FOR A FOCAL LENGTH OF 800MM TOTAL)

Move in Closer

Move in Closer

Use your telephoto lens (whether it’s an optical or a digital zoom), and move in as close as you can to a subject that pleases you. Get to the point where you think the subject is looming huge in the viewfinder. Then take two steps closer, and make the picture. Upload your favorite resulting image to the BetterPhoto.com contest.

EACH LENS has a limit as to how close it will enable you to get to your subject. This is called the close-focusing distance. Move in closer than this distance, and the lens will refuse to focus. So, what do you do if you want to take a picture of a tiny subject, such as a ladybug or the world inside a tulip, and the lens will not focus when you fill the frame with your subject? This is where specialized macro (close-up) modes and lenses come in. By turning on the macro mode (or using a macro lens), you enable the camera to photograph things in very close proximity.

Macro photography is exhilarating! You often see an entire universe open up right before your eyes. Small subjects—such as flowers, stamps, coins, jewelry, and insects—suddenly become large and beautiful.

Now that I don’t shoot slide film anymore, what do I do with my light box? I use it as a prop. For this image, I cut a kiwi into thin slices and placed them on my light box. I handheld my camera so that I was able to move it around until I found a composition that intrigued me, and once I did, I secured the camera to my tripod. The kiwi, when composed in this way, reminded me of a glorious sunrise.

2/3 SEC. AT f/16, ISO 100, 100MM MACRO LENS

For this image, I placed my camera securely on my tripod and attached a 100mm macro lens. I then placed two gummy fish candies on my light box. In one hand, I held my remote shutter release (to ensure that I did not move the camera at all when releasing the shutter), and in the other hand, I held a flashlight to add a bit of sidelighting that would bring out the texture of the colorful candy (which also made a delicious treat once I was finished with the shoot).

1/8 SEC. AT f/11, ISO 100, 100MM MACRO LENS

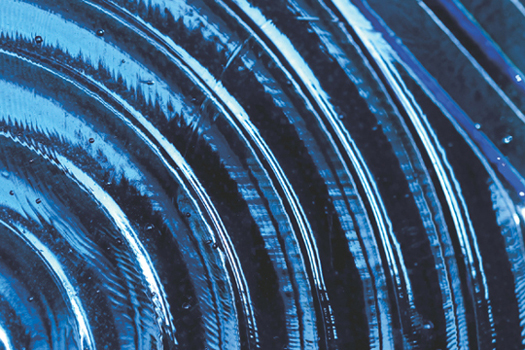

On a day trip to a local island community, I noticed a wall constructed of backlit blue glass blocks. I wanted to capture the beautiful quality of light as it filtered through the glass but knew that if I shot from a distance, the composition would include too many distractions. So, I placed my macro lens on my camera and moved in extremely close to one of the blocks.

1/350 SEC AT. f/5.6, ISO 100, 100MM MACRO LENS

When doing macro photography, make sure what you see in the camera’s “eye” is what you get in your final image. With an SLR camera, this is never a problem. You always view the scene through the same lens that your CCD uses. Therefore, what you see is what you get. In fact, this is one of the great advantages to using a digital SLR over a point-and-shoot digital camera.

With compact non-SLR digital cameras, what you see is not necessarily what you will end up with in the final image. Especially when you get superclose to your subject, the viewfinder—because it’s located at a slightly different spot on the camera and doesn’t look through the same lens—shows you a slightly different view.

To resolve this inconsistency in macro photography with a compact digicam, use the LCD screen as your viewfinder. With many digicams, this is the only option. The LCD monitor is forced to display continually when you turn the camera to the macro mode.

At all other times, I recommend that you do not use the LCD monitor as your viewfinder. Unless you’re doing macro photography, or shooting in unusual conditions that require the use of the LCD screen, look through the optical viewfinder instead. Among other things, this is a financial consideration: You’ll get a lot more mileage out of your batteries if you use the optical viewfinder to compose your nonmacro images. More importantly, it will help you create consistently sharp images by helping you hold the camera still.

WHAT THE LENS SAW

WHAT I SAW

RECOMPOSED VERSION

The first photo represents what I saw through the optical viewfinder when shooting with a compact, non-SLR Nikon Coolpix camera. The next photo shows what the CCD would have captured—I would have totally missed my subject! Noticing this discrepancy, I recomposed, shifting the camera to the left. I then used the LCD screen to compose in order to ensure that I got the image I was after. While I was at it, I decided to alter my point of view, getting down much lower than the flower. Looking up at it allowed me to get a pleasing color combination with the orange flower against the blue sky and green foliage. (For more on point of view.)

For this image, I sliced up a red onion into pieces of varying thickness and placed them on a light box in my garage studio. Before attaching my camera to my tripod, I looked through the optical viewfinder at each slice to determine which one looked best. During this process, I noticed this composition, which featured an off-center subject and made good use of the graphic pattern inherent in the onion slice. I then placed my camera securely on my tripod and made a variety of slightly different images. After each shot, I reviewed the image in the LCD screen to determine if I had captured the exact composition that I wanted. In this manner, I was able to reposition the subject and myself until I created the image I had in mind.

2/3 SEC. AT f/19, ISO 100, 100MM MACRO LENS

USE A TRIPOD FOR MACRO PHOTOGRAPHY

When doing macro photography, I highly recommend using a tripod. After discarding far too many “almost” photos, l can honestly tell you it’s worth the cost and inconvenience. It may be difficult to position the camera on your tripod. You may need to purchase a special attachment or invert the tripod’s center column in order to get close enough to your subject. But when shooting macro, depth of field is so shallow that the slightest movement can cause the wrong part of your subject to be in focus, and a tripod will really help keep things steady.

When examining this beautiful rose, I noticed an interesting graphic pattern in the petals that reminded me of a nautilus shell. I mounted my camera on a tripod and selected a macro lens, positioning the camera fairly close to the rose. During a long twenty-second exposure, I placed a handheld flashlight behind the rose, positioning it to give the rose a soft, unique glow. The LCD screen came in handy as my first few attempts suffered from a bit of strange flare (light bouncing back into the lens and causing distracting spots to appear in the image). Seeing this flare, I was able to reposition the flashlight to get cleaner, more pristine results.

20 SECONDS AT f/32, ISO 100, 100MM MACRO LENS

If your camera features a macro mode or if you own a digital SLR and macro gear, go out photographing macro subjects. First scout out the environment, searching for subjects to which you would like to get especially close. Anything small with detail generally works well. I like to look for interesting flowers, bugs, candies, sliced fruit, and the like. Usually, calm days are best for outdoor macro photography; if it’s windy, move indoors or to a sheltered location so that your subject doesn’t blur in the breeze. When you find a suitable subject, put your camera in the macro mode (or use a macro lens or extension tubes if you use a digital SLR) and place your camera on a tripod. Move in as close as you possibly can, and watch your tiny subject become huge and impressive.

PHOTOGRAPHERS ARE often disappointed with their images, saying that the scene was wonderful but the photos feel static and boring. This can frequently be fixed with another powerful compositional guideline: the Rule of Thirds.

You’ve probably noticed that placing your subject a bit off-center can actually be a good thing, adding an amazing degree of visual interest. In fact, placing your subject in the exact center of the composition more often than not detracts from the effectiveness of the photo.

The use of the Rule of Thirds goes all the way back to ancient Greece, and it works. It’s so effective that through the centuries, it has been passed down from artist to artist as an easy way to add vitality to your pictures. It works in photographs in the same way it has worked in paintings.

The general principle behind the Rule of Thirds is actually quite simple: Place your subject a little off to the side.

Not haphazardly, mind you. According to the Rule of Thirds, there are specific sweet spots for your subject. To find these sweet spots, imagine drawing four lines across your photo: Draw two evenly spaced horizontal lines and two evenly spaced vertical lines, like a tic-tac-toe game. The points at which the lines intersect are the sweet spots.

When composing any scene, you can position your subject at one of these four places (where these lines intersect). This allows the eye to pleasantly travel around the photo before coming to a satisfying rest on your subject. Even though this all happens for the viewer within a split second, this tour around the photo is likely to be enjoyable and satisfying. Furthermore, this careful placement helps the eye quickly determine what the subject is and what part of the photo deserves the most attention.

To determine which of the four points of intersection to use, you need to think about two things:

1 Is your audience in the Eastern Hemisphere or the Western Hemisphere?

2 What’s going on in the rest of the composition?

The first consideration has to do with how we’re trained to read and write. If you’re a Westerner like me and read from left to right, you may prefer offcenter subjects that are positioned on the right rather than the left. This placement encourages the eye to scan across the scene in an uninterrupted way from left to right until it reaches your subject.

The second consideration has to do with the environment surrounding your subject. If you notice distracting elements above your subject, you might want to place the subject on one of the two upper horizontal lines, thereby eliminating the distractions. If you notice an object that could play a nice supporting role above and to the right of your subject, you might place your subject in the lower left position. This will cause the two to play off of each other and is often an excellent way to balance out your subject or give it additional environmental meaning.

You may find it difficult to decide which intersection point to use. The differences between each composition can be subtle and hard to see. Try taking a couple of pictures to find out. Place the subject on the upper right Rule of Thirds intersection point. Then shoot a second time, with the subject on the upper left, and compare the two photos. You may feel that both ways work equally well. Often, the most important thing is just placing your subject on one of the Rule of Third sweet spots (rather than agonizing over which spot to use). The most important point is just using the Rule of Thirds in the first place.

Dividing your image into nine parts—by visualizing two lines cutting the composition into equal thirds on both the vertical axis and horizontal axis—sets you up to use the Rule of Thirds. Then, all you do is place your subject on one of the places where the lines intersect. This is a simple and effective guideline for producing interesting, balanced compositions.

1/350 SEC. AT f/10, ISO 100, 16–35MM LENS AT 35MM

There are two principle times you can apply the Rule of Thirds. We’ve just covered the first—placing the subject on one of the four sweet spots. The other is when you’re shooting a landscape and the composition includes the horizon. In my online photography courses, I often see students placing the horizon line in the middle of the photo. When the horizon falls in the middle, it effectively divides the image into two halves, and the viewer is left to decide which half is most important.

Before you press down that shutter button, decide which half of the photo, either the earth or the sky, comprises the main subject of the photo. Then, instead of cutting the composition in half, move the camera to reposition the horizon up or down within the frame to feature more of your main subject. If the sky is spectacular, move the horizon down to the lower third of the image to help the eye appreciate that amazing sky. When using the Rule of Thirds for scenes that include the horizon, you may not need to place the subject on a point of intersection; simply align the horizon with either the upper or lower horizontal line.

LOCK FOCUS

The key to getting sharp off-center compositions is to understand how the focus lock feature on your camera works. Generally, the idea is to first center your subject, press the shutter button down halfway, and then recompose, placing your subject on one of the Rule of Third sweet spots while still holding the shutter button halfway down. Once you position the subject exactly where you want it, press the shutter button down fully to take the picture.

1/250 sec. at f/4.5, iso 400, 100–400mm lens at 250mm

The first image is an ineffective composition. Placing the subject in the exact center of the photo splits the image into two equal parts. The eye doesn’t know what to do except look briefly at the central figure and move on.

The next one, on the other hand, is much more successful, with the most visually interesting element—the mountain lion’s face—in the upper right area of the frame. To do this, I first locked my focus on the lion’s face and then recomposed. I waited for the lion to look up before pressing the shutter, because my goal was to capture the exact moment when the lion either made eye contact with me or looked into the left side (my left) of the scene. Having the lion’s eyes in the upper right guides the viewer’s eye through the composition: scanning from left to right, then up the body to the payoff of the animal’s face, and finally back to the left where the lion is looking. This visual cycle produces a pleasant, satisfying experience for the viewer.

1/250 sec. at f/5.6, iso 400, 100–400mm lens at 260mm

The only time I don’t use the Rule of Thirds is when I’m aiming for an intentionally symmetrical look. At such times, I strive to have everything perfectly symmetrical, either from left to right, from top to bottom, or both. For example, a photo of a mountain lake with the trees reflecting in the water is a good candidate for horizontally centering the horizon line instead of placing it at the top or bottom third of the composition. Likewise, humorous photos often seem even funnier when the subject is perfectly centered and/or the composition is symmetrical.

When making portraits, treat the Rule of Thirds as you do when photographing landscapes with horizons. Portraits of people, pets, and wildlife often work best when the subject is horizontally centered, with the eyes on the upper horizontal line.

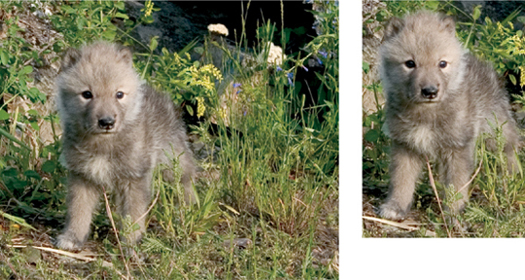

Here’s an exception to the Rule of Thirds. Since this was a portrait, I was inclined to center the subject on the horizontal axis. However, I also centered the main focal interest (his eyes) on the vertical axis. This doesn’t technically obey the Rule of Thirds, but it still works very effectively. Perhaps the viewer responds positively to the centered placement because it adds to the feeling of almost comical cuteness. Whether that’s the case or not, the point is that sometimes the “rules” are meant to be broken. As long as you’re aware of the rules, taking them into consideration when you compose your photo, don’t hesitate to experiment with bending them to fit the particular needs of the situation.

1/350 SEC. AT f/5.6, ISO 100, 100MM MACRO LENS

Portrait compositions can be made to obey the Rule of Thirds in a slightly different way: Instead of placing your portrait subjects off to the right or the left, you can center them vertically within the image but place the eyes along the upper horizontal Rule of Thirds line.

1/125 SEC. AT f/5.6, ISO 400, 100–300MM LENS AT 300MM

REMEMBER TO TURN your camera on end and shoot vertical pictures from time to time. Occasionally turning the camera and shooting in the vertical orientation is not just great for portraits; it’s also an excellent way to eliminate unnecessary clutter in all kinds of photos.

Each potential photograph tests you to frame the subject most fittingly. If turning the camera on end and shooting the subject in a vertical orientation eliminates attention-grabbing clutter or unnecessary negative space in the background, be sure to shoot at least one image in the vertical orientation. Without such distractions, the eye will find it easier to focus on the subject and your photo will be all that much more effective and powerful.

By habit, I shoot verticals almost all the time. After capturing a horizontal image of a scene I find particularly appealing, I turn the camera on end to capture a vertical version. Additionally, if a subject or scene is particularly challenging—it’s not working no matter what I try—I turn to the vertical orientation to see if it offers a more satisfying composition.

There’s also a psychological effect to take into consideration when deciding between a horizontal or vertical composition. Horizontal photographs tend to connote serenity while vertical photos come across as more active and dynamic.

Take both a vertical and a horizontal version of your favorite scenes and decide which version you most prefer later on when you review the results. You may have to work a little harder, shooting and editing more images, but at the very least, you will have more variety in your collection of photos.

Sometimes Both Work

While sometimes you will find that a subject works much better in one or the other orientation, at other times a subject will work equally well in both the vertical and the horizontal formats. The scene might not have any distractions that need to be eliminated by changing orientation. One version might simply tell a different story than the other, perhaps giving a more unique or startling impression of your subject. By all means, if this is the case, photograph the subject in both orientations.

1/250 SEC. AT f/6.7, ISO 100, 100–400MM LENS AT 135MM

Although I like both versions of this scene in Northeast England, most people respond with greater enthusiasm to the horizontal version. It does a better job of expressing the peaceful and recreational nature of the scene. It also communicates the impressive scale of the ruins in the background while showing the expanse of the land, something the vertical image does not do as well.

1/350 SEC. AT f/5.6, ISO 100, 100–400MM LENS AT 285MM

This is a nice example of the vertical format and how it can complement a subject. This man graciously agreed to pose for me with his standard poodle. I turned my camera on end and waited for the perfect moment—when they were both looking in the same direction. The image would not have been as striking if I had used the horizontal orientation.

1/90 SEC. AT f/5.6, ISO 100, 28–105MM LENS AT 28MM

As you look at a scene, decide which shape your subject best fits into: a vertical rectangle or a horizontal a rectangle? For this image, the vertical was clearly the orientation that better suited the subject. Turning my camera on its side allowed me to include only the elements that mattered and crop out the distracting, light background in camera.

Apply the Rule of Thirds to a Vertical Composition

Apply the Rule of Thirds to a Vertical Composition

Find a subject that you think fits well within the vertical orientation. Then lock focus on your subject and recompose until it is on or near a Rule of Thirds point of intersection. You’re going to like this assignment so much you’re going to start using the Rule of Thirds everywhere.

IF YOU FAIL to compose perfectly while shooting (in camera), fear not. As a digital photographer, you can turn to Plan B: cropping the image on your computer. Trimming the edges in a software program will often give you a second chance to apply the various composition concepts: moving in closer, the Rule of Thirds, and vertical vs. horizontal orientation.

The first image is the original, with my nose peeking in on the right edge. The shaded edges on the second image indicate what I cropped off on the computer.

See the cropped version.

Photo © Denise Miotke; 1/180 SEC. AT f/8

ISO 100, 28–105MM LENS AT 28MM

8 × 10

If you plan to place your images into standard 8 × 10-inch frames, you will likely need to trim your photo. With a vertical photo, the top and bottom edges will need to be cropped about an inch. With a horizontal photo, the left and right edges will need to be trimmed off. Keep this in mind when preparing an image for 8 ? 10-inch printing. If you want to keep more of one side, pre-crop the image. If you don’t, both edges will be trimmed equally when you go to print. If you don’t plan ahead, this could result in something important being cut out.

The first image appealed to me but never seemed to be a total success. I couldn’t figure out why until I realized that the subject (the man in the red hat) was fairly centered, with a great deal of negative space on both the right and left. I then cropped the image above in a way that placed the man on the lower right Rule of Thirds sweet spot and the supportive background object (the waterfall) more toward the upper left. This balanced the man with his environment, giving the composition more meaning and a feeling of completeness.

The man in the photograph is actually a fellow photographer whom I asked to pose for me. Never be afraid to ask for assistance if it might result in a great photo.

1/8 SEC. AT f/4, ISO 100, 28–105MM LENS AT 55MM

As easy and as fun as it can be to crop your image on the computer, you need to be aware of a few downsides. First and foremost, when you crop an image on the computer, you cannot print it as big as the original. Cropping removes part of the image, which means that there is less image material for you to work with when you’re printing. Trying to enlarge the cropped version to print as large as the original lessens the pixel resolution as the computer tries to stretch out less image material (fewer pixels) over the same amount of space. The result would be a fuzzier, less pleasing image. Notice how the three cropped versions of the same photo become smaller and smaller as printed images.

Another downside to computer cropping is that it takes time and a knowledge of the software. Furthermore, there are some changes that cannot be easily made in software, such as shifting your point of view or creating the fun distortions attained by using particular kinds of lens (see here).

The yellow, orange, and red boxes on the original image indicate how each subsequent image was cropped. The increasingly smaller picture sizes reflect that there’s progressively less and less image material to work with when printing.

1/250 SEC. AT f/4, ISO 400, 16–35MM LENS AT 27MM

MOST PEOPLE THINK of telephoto lenses—100mm or more—as accessories to help them get closer to a subject. It is true that this is a big feature of these lenses. However, another interesting thing happens when you use a long telephoto lens. The distance between your foreground and background objects appears more compressed. The more telephoto the lens, the more compressed this distance will appear. What once seemed far off in the distance will now look surprisingly close, as if the landscape had been compacted right before your eyes.

Using more telephoto lenses to compress the foreground and background can be a lot of fun, and it can be a powerful tool when composing objects in a photo.

1/10 SEC. AT f/22, SO 100, 28–105MM LENS AT 28MM

1/6 SEC. AT f/27, ISO 100, 28–105MM LENS AT 105MM

Most people understand that telephoto lenses make a subject look bigger and that wide-angle lenses let you include more in a scene. This is just the tip of the iceberg, though. Actually, what’s going on when you zoom in on a subject is that the distant object appears to be closer to the foreground. These three photos illustrate this. In the first photo notice how small the buildings appear in comparison to the foreground grass. For the next two photos, I walked increasingly further away from the subject as I zoomed in on it. This enabled me to keep the grass about the same size in each picture. As I increased my focal length, and then switched lenses to get even greater focal length, the buildings appeared much larger and closer to the foreground grasses.

1/45 SEC. AT f/10, ISO 100, 100–400MM LENS AT 250MM

Most people, when they want to get close to their subject, reach for their telephoto lens. And this generally makes sense. The telephoto magnifies distant objects, making it easier to fill the frame with the subject. However, there’s another possibility. You can instead choose a wide-angle lens or setting—such as 16mm or 20mm—and get as physically close to your subject as you possibly can. Take a look at these two examples to see what I mean.

Bad News for SLR Users: Wide Angle Lenses Aren’t So Wide Anymore

Unless you can afford a very expensive digital SLR camera, you will likely not be able to shoot wide-angle images like you can with a film SLR camera. The reason for this is that digital SLR cameras feature a chip smaller than a 35mm frame of film. This results in images being magnified, usually by about 1.5 times. In other words, a 20mm lens becomes the equivalent of a 28mm or 30mm lens when placed on your digital SLR.

Without spending serious money, wide-angle options are limited. So, if you are accustomed to shooting super-wide-angle images, remember that the SLR lens magnification factors of digital SLR cameras will make this difficult or impossible.

For a period, I particularly enjoyed photographing extremely wide-angle images—those in which the subjects became uniquely distorted and visually compelling. When I bought my first digital SLR camera, I lamented the fact that, because all my lenses were now magnified, I no longer could create those wacky and wild super-wide-angle images. Over the months, however, I forgot about this loss. It wasn’t until a lot of time and images had passed that I realized that, subconsciously, I had found a way to work around the wide-angle problem. I was simply moving back whenever I needed to get a wider angle of view in the picture. Oh so simple … and yet so effective.

To create this comical “Mr. Ed” kind of image, I used a 16–35mm wide-angle zoom lens and made it as wide as possible. I then got extremely close to the horse (my lens would have been “slimed” if it had stuck out its tongue) and shot from a low point of view.

1/45 SEC. AT f/19, ISO 100, 16–35MM LENS AT 16MM

Four Lens/Proximity Options

Telephoto Lens/Close to Subject. This combination is often great for macro photography and tight detail shots of close-up objects.

Wide-Angle Lens/Close to Subject. This combination often produces comical, wild views with lots of distortion.

Wide-Angle Lens/Far from Subject. Great for scenic landscapes encompassing entire vistas, this more traditional use of the wide-angle lens can create some amazing, expansive compositions.

Telephoto Lens/Far from Subject. The traditional use of the telephoto lets you bring the unapproachable within reach (e.g. wildlife, kids, athletes).

Before trying to photograph this subject, I selected my 16–35mm wide-angle zoom lens and tripod. Then, for about twenty or thirty minutes, I worked on approaching this cow so as not to frighten her off. I started by trying to coax her and her friends closer to the fence with some grass to eat. Although I told her it was “the good grass” from the other side of the fence, she didn’t buy it. After I felt I had been near long enough for the cows to feel somewhat comfortable with my presence, I slowly climbed the fence and stood closer to them. I waited patiently and moved in a bit closer every few minutes. After some time, they fully accepted me as one of the herd. This particular cow that I had been trying to photograph gave me a bonus by sniffing my camera lens and giving me some curious close-up looks.

1/350 SEC. AT f/10, ISO 100, 16–35MM LENS AT 16MM

After a couple of hours spent photographing this rancher at work branding his cattle, I asked him if he wouldn’t mind posing for me one last time. He reluctantly agreed, and I led him back to the cow pasture. After adjusting his pant legs to show off his interesting boots and positioning myself flat on my belly on the ground, I fired off several compositions with a wide-angle lens. My goal was to get an image with his boots in the foreground and a cow in the background. This was the first exposure I made, and it turned out to be the best.

1/45 SEC. AT f/16, ISO 100, 16–35MM LENS AT 16MM

IN ADDITION TO using a variety of lenses and orientations, getting in close and keeping the Rule of Thirds in mind, you can also create unique compositions by altering your point of view—changing the position from which you take the photo.

By getting low, for example, you can photograph your kids or small animals on their level, instead of looking down on them. Getting even lower on the ground and aiming up at a subject like a flower, enables you to include the sky in your background and treat your viewers to something new and unique, something they wouldn’t likely have ever seen without your help.

Conversely, getting above your subject will also produce a unique composition. Getting slightly above a person makes them appear a bit smaller (and thinner). Climbing up on top of a ladder will give you a unique point of view when photographing scenes like fields, with any crop rows producing strong and compositionally valuable lines. We’ll talk more about how graphic elements, such as line, shape, and pattern, can be photographic gold mines. For now, just remember to ask yourself before taking each picture, Will changing my position produce a more interesting and unique point of view?

1/250 SEC. AT f/5.6, ISO 100, 100–400MM LENS AT 400MM

These two photos capture the same subject: a bobcat kitten. The subject in the first photo, however, looks nothing like the subject in the second. Why is that? Simply because I used different lenses. For the vertical photo, I stepped back away from the kitten and used a long telephoto lens (100–400mm telephoto zoom lens at 400mm). The background is dark and nondistracting, the light is good, and the subject is cute.

For the horizontal photo, I changed to a 16–35mm wide-angle lens and got very close to the kitten. I was actually about an inch away and slightly below it, but the wide-angle lens makes it look like I was farther away. More importantly, it caused a slight distortion in the subject and scene. Even though I like the first photo, I like this one even more because it is so much more unique and unusual. The blue sky in the background adds a pleasing splash of color.

On another note, the second photo is a good example of when having a photo assistant comes in handy: My wife was snapping her fingers and jingling a set of car keys just above my head to keep the kitten’s attention directed toward the camera.

1/100 SEC. AT f/5.6, ISO 100, 16–35MM LENS AT 16MM

1/125 SEC. AT f/4.5, ISO 100, 28–105MM LENS AT 105MM

1/180 SEC. AT f/4.5, ISO 100, 28–105MM LENS AI 105MM

The background in the vertical image is cluttered and unattractive. By simply changing my point of view, I was able to simplify the background-find make it complement the foreground tulip.

1/350 SEC. AT f/6.7, ISO 100, 100–300MM LENS AT 300MM

1/500 SEC. AT f/6.7, ISO 100, 100–300MM LENS AT 300MM

My first attempt with this subject was too cluttered for my taste. To capture the second photo, I simply squatted down to get a lower point of view. This caused the tulips in the background to merge into one unified carpet of yellow, which was an improvement. Then, I walked closer to the subject to make an isolated portrait of the lone pink tulip in the third photo.

1/500 SEC. AT f/6.7, ISO 100, 100–300MM LENS AT 300MM

When I took this photo, I was standing on a five-gallon bucket for a slightly higher vantage point. Aiming the camera down on my subjects caused them to look up at the camera. This helped create a nice look, and the slightly altered point of view resulted in a less run-of-the-mill portrait.

1/200 SEC. AT f/10, ISO 1600, 28–105MM LENS AT 98MM, FILL FLASH

By standing on a chair and positioning the camera almost directly above my subject, I was able to both minimize distractions and capture an image with a unique point of view.

1/160 SEC. AT f/4.5, ISO 100, 28–105MM LENS AT 28MM

Get Down, Get Up, Get Wacky, Get Wild

Get Down, Get Up, Get Wacky, Get Wild

Think of a subject that you can shoot at relatively close proximity, a subject that you can either get above or below. Some possible subjects might include pets, family members, flowers, and fields. Avoid distant landscapes, cityscapes, and other far-off subjects, as these will not be affected as much by a change in point of view.

First, take a few pictures at your standard height. Then, get down on the ground. Don’t worry about getting dirty or being embarrassed—these are the risks you have to take to produce great photos. Once you’re in an extremely low position, shoot up at your subject, remembering to keep as close to it as possible. Watch out for bright overcast skies in the background. These can wreak havoc on your exposure. When the sky is overcast, try to change your point of view so that a darker element is in the background. If this isn’t possible, just be sure to adjust your exposure settings to favor your foreground subject. (See chapter 4).

Finally, find something that you can stand on, such as a stepladder, chair, bench, five-gallon bucket, or other supportive container. Be careful to keep your balance, and then photograph looking down on your subject from this higher vantage point.

When you’re done, compare the results and think about the different psychological effects each point of view produces. Select your favorite and show it to your friends and family, or upload it into the contest or galleries at BetterPhoto.com.

LINE, SHAPE, AND PATTERN are the final design elements of a composition to consider. They are the ingredients with which top-notch photographers work. Recognizing these elements is the first step toward making exciting, graphic photographs. And, looking for them can be extremely fun. When you find these graphic elements, use them thoughtfully in your photographs. As you read about each of the following elements, consider how you might put them to use in a future photo.

Line is one of the most readily available and visually powerful graphic elements to use in a photograph. Lines are not difficult to find—they’re all around us. They can be curved or straight, long or short, fat or thin. However, as with all design elements, it’s not enough to just shoot line. If you notice a strong line in a scene, you can do more with it than simply snap a picture of it. Arrange the various objects in your composition so that the line leads up to the subject. Give the eye a “pay off,” a reward for following the line all the way into your composition. Use line to guide the eye through the image on a fun journey. Take your viewers by the hand on a visual tour of your photograph instead of just plopping them in the middle and letting them wander.

GET IN LINE

Whenever you notice a strong line in a scene—whether it’s curved or straight—look for some interesting object to use as a visual “destination” for the viewer. Then choose a composition that causes your line to lead the eye to that point.

In England’s Lake District, I noticed the irregularly curving line formed by this stone wall and admired the way it divided the hillside. The line leads the eye on a pleasant journey into the scene.

1/125 SEC. AT f/8, ISO 100, 28–105MM LENS AT 105MM

Shot in Yosemite National Park, this could have been a standard (and boring) photo of a waterfall. By placing the crooked walkway in the foreground, however, I was able to add a lot of interest and impact to the photo.

1/8 SEC. AT f/22, ISO 100, 16–35MM LENS AT 17MM

While photographing another image (see here) I turned and noticed this father and son approaching, with the son acting as the perfect payoff. Here’s proof that lines are indeed all around us!

1/125 sec. at f/5.6, iso 100, 1000–400mm lens at 100mm

The character of line can change dramatically simply by the way it is oriented. When lines are horizontal, the visual effect is calming and static. When vertical, lines connote strength and power.

Note how there are two sets of lines at work in this image of an iron door in a historic mining town in California. The converging lines of the floorboards lead the eye into the scene and add a bit of perspective. The vertical lines in the door take you where the lower lines leave off and give the door an air of towering strength.

1/125 SEC. AT f/4.5, ISO 100, 16–35MM LENS AT 35MM

When positioned diagonally, lines can be especially eye-catching and dynamic. Compare these two images to see what I mean.

BOTH PHOTOS: 1/180 SEC. AT f/6.7, ISO 100, 16–35MM LENS AT 33MM

A photographer with a good eye is ever on the lookout for shapes, such as triangles, rectangles, squares, circles, and ovals. When you notice one of these shapes in a scene, position yourself or your subjects in a way that accentuates or balances out the shape.

Shapes can be made more evident by contrast, when one object is much darker or lighter than a neighboring one. Silhouettes provide excellent opportunities for focusing on shape. When a silhouette image is exposed properly, the foreground objects are rendered black, with crisp sharp outlines separating them from the brighter background. Silhouettes eliminate any sense of depth in the subject and cause it to be seen as a simple shape.

Silhouettes can be an awesome source for subjects that emphasize shape. Since the main subjects are rendered as pure black, they become flat shapes. This graphic nature of silhouettes becomes all the more evident when the subject is set against an equally simple background, such as this orange sky.

1/90 SEC. AT f/74.5, ISO 100, 100–400MM LENS AT 100MM

Shadows can be another great source for compositions that emphasize shape. Keep an eye out for shadows when photographing any subject. If you notice an interesting, distinct shadow, be sure to include it in your composition, carefully arranging things so that the shadow is balanced with the other elements in your photo.

1/90 SEC. AT f/5.6, ISO 100, 100–400MM LENS AT 260MM

DON’T MERGE

When emphasizing shapes, shadows, and silhouettes, make sure the forms do not merge with one another. Keep each element distinct and separated. If shapes are touching or merging together, try to reorganize your composition by shifting your point of view. Your goal: to keep those shapes simple, distinct, and orderly.

This composition also makes use of both line and shape: The strong lines formed by the green hedges define the shapes.

1/500 SEC. AT f/8, ISO 100, 100–400MM LENS AT 400MM

Many scenes feature more than one graphic design element. This image could be seen as an example of line (with the one strong line of ice in the middle of the leaf), shape (with the three shapes created by this diagonal dividing line), and pattern (with the pattern formed by the cracked ice covering the leaf).

1/20 SEC. AT f/11, ISO 1600, 100MM MACRO LENS

Pattern-is an organized series of graphic elements, such as lines or shapes. To be easily recognized as a pattern, there needs to be at least three or more repetitions of the elements. Five or more repetitions make the pattern even easier to see. Including an odd number of repeating elements seems to be more pleasing to the eye than including an even number of repeating elements.

Whatever these repeating elements are, they need to be arranged in an organized way. The most important aspect of this arrangement is that you exclude extraneous elements. Nine times out of ten, moving in closer will cause the pattern to become more apparent.

It’s good, when photographing patterns, to find one thing that doesn’t fit into the pattern—an anomaly. In this photo, the anomaly is the boy with the red umbrella, red shirt, and red socks who breaks up the linear pattern created by the rows of daffodils.

1/250 SEC. AT f/6.7, ISO 100, 28–105MM LENS AT 105MM

The natural world provides an abundance of photo opportunities when it comes to shooting patterns. The patterns found in nature are often soft, curved, and flowing—such as spider webs, ripples in sand or water, and flowers. Even more so than when they’re represented individually, curving lines, when arranged into a nice pattern, have a pacifying effect on the viewer. They evoke a feeling of serenity. Sometimes, patterns in nature are straight and angular. Keep an eye out for these unique natural patterns; they are, in photographic terms, pure gold!

However, nature does not by any means have a monopoly on pattern—or any design elements, for that matter. Cities, roads, traffic, and millions of manmade objects offer excellent opportunities to photograph patterns. Fields of crops—good combinations of the natural and the manmade—can be a wonderful place to find strong patterns. In the urban, manufactured world, look for patterns comprised of straight hard lines, right angles, triangles, and rectangles, some of which are rarely found in nature. If you happen to find a soft, curving line or pattern in the manmade world, make the most of it.

You can find interesting lines, shapes, and patterns in both the natural world and in environments that have been changed by man. These design elements are everywhere! All you have to do is learn to recognize them, and once you find them, use them thoughtfully in your compositions.

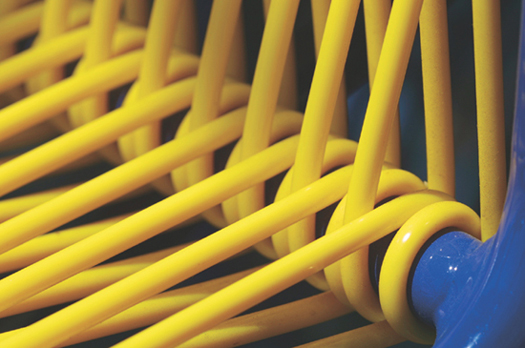

In this image, the anomaly is the bit of blue in the lower right corner, which adds interest to this study of color and pattern. To get this image, I used my macro lens and moved in close to a two-seater bicycle seat.

1/500 SEC. AT f/6.7, ISO 100, 100MM MACRO LENS

ONE OTHER ELEMENT of composition and design to keep in mind is framing. Whenever you notice lines surrounding your subject—either above, below, or on the sides—see if you can use them to create a natural frame around your subject. This will help keep the eye on the subject of the composition.

The idea here, like the Rule of Thirds, goes way back. Artists have known for centuries the value of framing their subject. Surrounding a scene with an edge—and, if possible, including negative space around an object—causes it to stand out more. Modern framers understand this when they place a picture in a big white mat before framing it. Photographers can also put this rule to use by composing the scene so that surrounding elements that occur naturally in the scene frame the main subject.

My wife photographed this cute baby raccoon at Triple D Game Ranch in Montana. The surrounding log provided a natural and perfectly complementary framing device. Photo © Denise Miotke

1/45 SEC. AT f/5.6, ISO 100, 28–135MM LENS AT 90MM

This pastoral scene benefits greatly from the horizontal branch along the top edge, which keeps the eye from wandering off that edge and helps frame the overall scene.

1/2 SEC. AT f/22, ISO 100, 16–35MM LENS AT 35MM

Make Use of Line, Shape, Pattern, and Framing

Make Use of Line, Shape, Pattern, and Framing

You can do this assignment anywhere. It’s easy, fun, and opens up wellsprings of inspiration. This is when we get to put the “graphic” back in “photographic.” Go out on a treasure hunt for the three graphic elements of design: line, shape, and pattern. Once you find them, work with these elements in a meaningful way, incorporating them into your compositions. Line should be evident and put to good use. Shape should help create a clean and simple composition. And, pattern should be used in a pleasing way. While you’re doing this, try to think about how you’re framing your images, as well.

Regardless of which kind of camera you use, you can put these principles of composition to use. Move in as close to your subject as you can—with a telephoto lens, by walking up closer, or with a wide-angle lens for that fun, distorted effect. Balance your subject with its environment by using the all-time classic Rule of Thirds. And remember, turn your camera on end from time to time, whenever you think your subject might be better suited to the vertical orientation.

While this image doesn’t make obvious use of a tree branch or other naturally occurring physical element to frame its subject, the foreground earth and background railings and cowboys serve to frame the cows, which occupy the entire width of the image, all condensed into relatively the same part of the picture plane. This highlights the cows and divides the composition pleasingly into three horizontal bands (the foreground, the cows, and the background). Actually, the real reason I wanted to end the chapter with this image is that I find it funny.

1/125 SEC. AT f/5.6, I SO 100, 16–35MM LENS AT 35MM