Annotations for Leviticus

1:3 burnt offering. This category of sacrifice, in which all edible material was burned, served as a basic and general gift and was meant to invoke the deity (cf. Ge 8:20; Nu 23). At least one was offered each day on behalf of the people of Israel, and festivals and ceremonies would include them as well. Burnt offerings were practiced by other ancient Syro-Palestinian peoples, whose rituals were closest to those of the Israelites. They were also performed in Anatolia, but apparently not in Egypt or Mesopotamia. In Ugaritic literature, where words for several kinds of outwardly similar (but by no means identical) sacrifices parallel Hebrew terms, burnt offerings are often coupled with well-being offerings (“peace” or “fellowship” offerings; see notes on Lev 3:1, 11), as they are in the Bible (e.g., Ex 20:24). So we see that Israelite sacrifice was not an isolated phenomenon. There have been many theories as to what purpose animal sacrifice was to serve. In some cultures it was seen as caring for the deity by providing food (see the article “Great Symbiosis”). Others saw the sacrifice as a gift to please or request aid from the god. Still others saw the sacrifice as a means of entering into relationship. The earliest Sumerian literature indicates that sacrifice was used as a means of allowing meat consumption, as the process of sharing meat with the deity allowed them to slaughter the animal for food. In Assyria and Babylon, animals were sacrificially slaughtered in order to obtain the entrails, which were used for divination. from the herd. In ch. 1, objects of sacrifice are logically presented in descending order of size and value. Similarly, a third-century BC Punic sacrificial tariff (the so-called Marseilles Tariff from Carthage) lists fees for priestly officiation in descending order, corresponding to the decreasing sizes of the sacrificial animals. male. Male animals were both expendable and valuable. Many females were required to sustain the herd by bearing young, but only a few males were necessary. On the other hand, strong males were desirable because their genetics would be reflected in a large portion of the herd.

1:4 lay your hand on the head. In Hittite ritual, this gesture appears to carry the same function of identifying the owner as the one who is giving the sacrifice, perhaps analogous to the signature on a letter. Even though the priest “delivers” the offering, this gesture signifies that the offering comes from the one who “signed” it. make atonement. The Hebrew word (kipper) refers to the removal of ritual impurity. Most scholars now agree that “atonement” (“reconciliation”) is a poor translation of the concept on either a ritual or theological level. In the past, it was common for scholars to connect kipper with Arabic kafara (“cover”) and to interpret a ritual accomplishing kipper as “covering sin” (see Ge 3:6–7; Zec 3:3–5). In the context of purification offerings (“sin offerings”), though, kipper followed by the Hebrew preposition min (“from”) denotes removal rather than covering. Furthermore, the grammatical object of kipper in Hebrew is generally neither the sin nor the person, but a holy object such as the ark or the altar (e.g., Ex 29:36). Finally, in a number of cases this process is necessary even though no sin has been committed. Therefore, recent scholars prefer the terminology of “purification” or “purgation” (in this case, of the altar) on behalf of the individual whose ritual impurity (caused by sin or otherwise) has tarnished it. The ritual, like a disinfectant, is usually remedial, but can be preventative as well, and usually (but not always) uses blood as the reagent. The decontamination process renders the offender “clean” and paves the way for reconciliation, but the actual word kipper refers to the decontamination process, not its final results. The idea of removal is also present in the Akkadian cognate kuppuru. In ritual or medical usage, this term usually denotes a physical wiping that is directly applied to persons or things from which evil is removed, though this and other examples from the ancient Near East are usually magical in nature (see the article “Magic”).

1:5 bring the blood and splash it. Blood represented life (17:11). The idea that blood contained the essence of life is evidenced in the use of blood (of a slain deity) to create the first people in Mesopotamian cosmogony. By contrast to the Israelite ritual system, in which blood was intentionally and meaningfully applied in various ways (splashing, sprinkling, daubing, etc.) to objects, areas and persons, Mesopotamian and Ugaritic cults lacked such ritual use of blood. In some ancient cultures (Hittite, Greek), blood could be used for libations to underworld deities, conveyed to them by means of ritual holes in the ground. One ritual, involved in establishing a new Hittite temple for the “Goddess of the Night,” purified the new deity and temple by bloodying the golden image, the wall and all the implements of the deity. A Greek ritual for purification from homicide called for the slaughtering of a piglet over the head of the person undergoing purification, followed by the rinsing off the blood. In another Greek purification ritual, officials carried a piglet around the city square in Athens, then slaughtered it, sprayed its blood over the seats, and discarded the carcass. These practices somewhat resembled Israelite purification (“sin”) offerings, the blood of which was used to purify persons, objects and places (see notes on 4:3, 35; 16:14). Unlike the Greek purifications, Israelite sacrifices applied blood to part of the sanctuary/temple of their deity, such as an altar. splash it against the sides of the altar. A symbolic means of applying the death of the animal to the purging of any contamination that might interfere with the function of the sacrifice. See note on v. 4.

1:9 food offering. The Hebrew term ishsheh derives from the word for “fire” (esh). Weakening this idea, ishsheh can refer to food portions that are eaten rather than burned (Dt 18:1), and it also is never used of purification (“sin”) offerings, which are always burned. However, scholars have found an alternative in an Ugaritic cognate (the same word in another language) that means “gift.” This concept fits the Biblical contexts well: An offering is given to God, whether it is burned or not, but the purification (“sin”) offering (where ishsheh is not used) is not a gift because it is a mandatory token payment of “debt.” an aroma pleasing to the LORD. Other ancient Near Eastern peoples also viewed deities as favorably disposed to the smell of incense and offerings. But whereas Israel’s deity does not need human food (Ps 50:12–13), other nations’ gods were thought to be dependent on such sustenance. In the Ugaritic Baal Cycle, when the god Ilu sees the goddess Atiratu coming to him, he says to her, “Are you really hungry (because) you’ve been wandering?” In the Babylonian Atrahasis epic, the gods suffer from hunger and thirst during the great flood because there are no humans to offer them sacrifices. Therefore, when Atrahasis (the Noah-like figure) subsequently offers his sacrifice, the gods smell the offering (cf. Ge 8:20–21), and they crowd around like flies. Unlike Yahweh, they enjoy the smell because it promises an end to their hunger. In a Hittite prayer, King Mursili II pointedly uses the gods’ need for food as an argument to plead that they remove a plague from his land, lest they suffer because of a lack of humans to serve them.

2:1 grain offering. Throughout the ancient Near East, people frequently presented sacrifices consisting of grain, which was a staple in their diet. While grain offerings could be independent (as in ch. 2), they were often served with drinks as accompaniments to animal sacrifices (Nu 15). Thus, on the fifth day of the Hittite Ninth Year Festival of Telipinu, the god was to be offered choice meat portions (of 10 bovines and 200 sheep!), plus thick breads and drink offerings (see note on Lev 7:7).

2:11 you are not to burn any yeast or honey. The reason for excluding yeast from the altar was mostly that leavening involves a kind of decay through fermentation. Along the same lines, honey (most likely syrup from fruit, not the by-product of bees) was banned from the altar because of its susceptibility to fermentation. Fermentation was associated with death and therefore excluded.

Non-Israelite peoples frequently offered honey to their gods. Thus in Assyria and Anatolia, honey (along with other liquids, such as oil and wine) could be poured into a ritual hole in the ground as a libation for an underworld deity. The final ritual of the fifth day of the Babylonian New Year Festival of Spring was a burnt offering to celestial gods that included honey, along with ghee (clarified butter) and oil.

2:13 salt of the covenant of your God. Salt was the finest preservative in antiquity, and it symbolized permanence and preservation. Salt was probably used in the covenant ceremony in which Israel celebrated its unbreakable covenant with God. The salt that accompanied many Israelite sacrifices was used physically in the seasoning of the elements, but it also symbolically contributed to the quality of the covenant relationship between humanity and God. In antiquity, parties who shared salt (here the Lord and the Israelites) were united by mutual obligations. Thus, a letter from Neo-Babylonia refers to a tribe’s covenantal allies as those who “tasted the salt of the Jakin tribe.” Similarly, the Greeks salted their covenantal meals, and in Ezr 4:14 those who tasted the salt (the literal Hebrew) of the Persian king’s palace were bound to loyalty to him.

Since human allies establishing a covenant would commonly share a meal featuring salted meat, it made sense for the salt in Israelite sacrifices to serve as a reminder of the covenant between God and Israel. Because salt was employed as a preservative, its use in a covenantal context also emphasized the expectation that the covenant would last for a long time, a meaning attached to salt in Babylonian, Persian, Arabic and Greek covenant contexts. Because salt inhibits the leavening action of yeast, which represented rebellion, salt could additionally stand for that which prevented rebellion. An additional explanation for the appropriateness of salt in connection with the covenant is found in its association with agricultural infertility: In a Hittite treaty, the testator pronounces a curse: if the treaty is broken, “may he and his family and his lands, like salt that has no seed, likewise have no progeny.”

3:1 fellowship offering. The Hebrew term for this kind of sacrifice is from the same root as the well-known word for “well-being/peace” (shalom) and is better understood as “well-being offering.” A sacrifice designated by a noun from the same Semitic root appears frequently in Ugaritic ritual texts, especially in tandem with burnt offerings (see note on 1:3). The chief difference between a fellowship offering and a burnt offering was that in a fellowship offering the offerers (and others with whom they could share) ate meat from their own well-being offerings as sacred meals shared with their deity; in a burnt offering the offerers were not permitted to partake of the offering.

3:4 fat. “Suet” is the layer of fat around the internal organs. It is inedible and easily removed. Mesopotamians did not include suet in their sacrifices, but many other cultures did.

3:9 fat tail. When a flock animal is offered, the “fat tail” is included in the sacrifice. Sheep of this region had long (4–5 feet, or 1.2–1.5 meters) tails weighing up to 50 pounds (23 kilograms).

3:11 food offering. Offerings presented to the Lord at the outer altar are called the “food” of God (21:8; Nu 28:2). Non-Israelite peoples also offered food, but they regarded their deities as needing to consume it (see note on Lev 1:9). As part of the daily care and feeding of the gods, Egyptians, Hittites and Babylonians regularly placed various kinds of food and drink on tables or stands before idols in their temples. In Hittite cults, consumption of bread offered to a deity could be symbolized by breaking it. In Egypt, care of the gods included not only feeding them, but also washing and clothing their idols and even providing them with painted makeup. See the article “Great Symbiosis.”

To complicate matters, many ancient Near Easterners believed that dead people continued to live on in divine form. This meant that those living were required to provide food and drink for these powerful and potentially dangerous spirits, lest they return from the grave hungry, thirsty and angry (see note on Dt 5:16).

In contrast, while Yahweh accepted food to affirm that he dwelt among them, he did not need it for nourishment (Ps 50:12–13). Therefore, the food was burned up so that he only received the smoke.

4:2 sins unintentionally. In the ancient Near East, deities were believed to possess superhuman powers of perception and to hold human beings accountable for their faulty actions, whether or not they knew that they had done wrong. Therefore a person could suffer evil consequences without knowing why. One Egyptian prayer asks a god for mercy: “Visit not my many offenses upon me, I am one ignorant of himself. I am a mindless man, who all day follows his mouth, like an ox after grass.” This kind of uncertainty was compounded by the difficulty of discerning what deities wanted and expected from humans. One Mesopotamian “righteous sufferer” expressed this problem: “I wish I knew that these things were pleasing to a god! What seems good to one’s self could be an offense to a god. What in one’s own heart seems abominable could be good to one’s god!”

Such uncertainty demanded a solution. Besides knowing which sacrifices, incantations or magical rituals to perform in order to appease deities or otherwise turn away evil (which could originate from the gods themselves or from demons), priests often practiced divination to sort out the variables, such as why the gods reacted as they did and what would placate them. In Israel, divination was unnecessary, because several factors greatly simplified reconciliation with the Lord: (1) In monotheism there was no need to determine which deity to approach. (2) Sin that required a ritual remedy was defined as violation of a command that the Lord had explicitly communicated to the Israelites. (3) Israelites who committed inadvertent wrongs (results of either accident or ignorance) were liable for presenting purification (“sin”) offerings only when they came to know what they had done wrong (vv. 14, 23, 28; but see note on 5:17). (4) A limited number of ritual types (burnt, purification [“sin”], and reparation [“guilt”] offerings) were prescribed to remedy a wide range of offenses.

4:3 sin offering. This sacrifice was necessary when someone’s actions or status resulted in something that was sacred becoming exposed to impurity. This sacrifice purified offerers (throughout the year) or parts of the sanctuary (at its consecration and on the Day of Atonement) from moral faults, or from physical ritual impurities, which were not sins in the moral sense (12:6–8; 14:19). Thus, the name of the sacrifice is better translated “purification offering” (see NIV text note). The procedure was unique in requiring application of blood to the horns of the outer altar or the incense altar. This ritual has no close parallel outside Israel (cf. note on 1:5).

4:12 burn it there in a wood fire on the ash heap. There is no indication that remnants of Israelite purification (“sin”) offerings were regarded as having absorbed dangerous demonic impurity. By contrast, a Hittite law warns: “If anyone performs a purification ritual on a person, he shall dispose of the remnants (of the ritual) in the incineration dumps. But if he disposes of them in someone’s house, it is sorcery (and) a case for the king.” The offering is burned so that none of it benefits the human offerers.

4:35 forgiven. The intended result of the purification (“sin”) offering is forgiveness. Only God can forgive (the Hebrew verb used here never has humans as the subject) and forgiveness does not rule out punishment (cf. Nu 14:9–24). The one who brings the offering seeks reconciliation—i.e., restoration of relationship—not pardon from punishment.

5:1 public charge to testify. In the ancient Near East, it was common for heralds to make public proclamations and summons. For example, the Code of Hammurapi reads: “If a man should harbor a fugitive slave or slave woman of either the palace or of a commoner in his house and not bring him out at the herald’s public proclamation, that householder shall be killed.” The procedure was similar in Israel, where compliance of witnesses, whose negligence could easily go undetected by human beings, was enforced by the deity. Following discovery of a crime, an imprecation invoking divine punishment would be pronounced on anyone who had knowledge but did not come forward. Serving as a witness against a member of one’s community could be uncomfortable or even hazardous. Thus the early Mesopotamian Shuruppak composition advises: “Do not loiter about where there is a dispute. Do not appear as a witness in a dispute” (cf. Pr 26:17). In Lev 5 the concession of amnesty through a purification (“sin”) offering for the deliberate sin of failure to respond to a binding summons to testify would encourage reticent witnesses to speak up even though they have delayed. they will be held responsible. The idiom here indicates that “they will bear their culpability.” Culpability is viewed as a burden that inevitably leads to punishment, unless or until someone takes it away. To illustrate the concept that a higher authority requires the punishment of the culpable, compare the Turin Judicial Papyrus regarding judgment on conspirators against Pharaoh Ramses III: “And they examined them; they found them guilty; they caused that their punishment overtake them; their crimes seized them.” Here the judges are human, but in ch. 5 it is God who sees to it that culpability bears its fruit, even if the guilty party is not apprehended by other human beings.

5:5 confess. Confession is necessary here because the faults in question are not inadvertent but have been hidden deliberately (v. 1) or were the result of forgetfulness (vv. 2–4). Other ancient Near Eastern peoples were also keenly aware that confession was a vital part of restoration. A Sumerian poem of confession and reconciliation shows several important points of contact with Biblical teaching regarding the sinful nature of the present human condition, need for recognition of sins, distinctions between sins in terms of whether they are recognized/visible or forgotten, and the value of sincere (rather than artful) confession and supplication in gaining reconciliation with the deity so that joy rather than punishment results (cf. Ps 51).

5:15 sinning unintentionally in regard to any of the LORD’s holy things. Respect for holy things, such as gifts dedicated to a deity (cf. Nu 18), was basic to all ancient Near Eastern religion. The Hittite document “Instructions to Priests and Temple Officials” takes pains to specify and prohibit several categories of sacrilege, including temple personnel appropriating sacrificial portions that are not theirs or taking dedicated things from the temple for their families, and farmers cheating gods out of property or delaying presentation of dedicated offerings. At one point the document warns: “You may steal it from a man, but you cannot steal it from a god. It (is) a sin for you.”

5:17 even though they do not know it, they are guilty. Here the reparation (“guilt”) offering addresses the problem of suspected but unidentified sin, which could constitute sacrilege and lead to adverse consequences, regardless of intention. A prayer of Ashurbanipal expresses similar uncertainty: “[Through a misdeed] which I am or am not aware of, I have become weak!” Notice that circumstances indicate divine disfavor. Similarly, one ancient writer recorded that when the Anatolian deity Telipinu became angry, he disappeared and took fertility with him until ritual appeased him. Unlike other ancient Near Eastern people, when an Israelite could identify no particular sin but was led by circumstances to suspect that he/she was no longer enjoying divine favor, there was only one deity to approach and only one kind of sacrifice to offer (see note on 4:2).

6:2 entrusted to them or left in their care. Verses 1–7 deal with cases of sacrilege that involve fraud: misuses of the divine name by swearing falsely in order to avoid human detection of an act that takes advantage of another person. In the ancient Near East, oaths were used to resolve disputes when other evidence was insufficient (see the article “Divine Verdict”). One person (the depositor) has deposited goods with another (the receiver) until such time as the first person will require the goods again. The Code of Hammurapi considers what to do in a variety of situations: if the receiver lies and claims no deposit was ever made; if the depositor claims a deposit was made but has no witnesses to prove it; if the deposited goods are taken by a thief (the law says the receiver must compensate the depositor for the stolen goods); and if the depositor lies and claims his goods have gone missing when, in fact, they have not.

6:9 the fire must be kept burning on the altar. The Hittite “Instructions to Priests and Temple Officials” also regulate fire at the residence of a deity; however, the concern is the opposite: to put the fire out at night so that it does not burn down the temple.

7:7 They belong to the priest who makes atonement with them. In ancient Near Eastern religious cultures, it was common for priests to eat portions of food that had been dedicated to deities (see note on Nu 18:9). Thus on the fourth day of the Hittite Ninth Year Festival of Telipinu, the priests ate sacrificial meat that had been presented to the god Telipinu.

The Hittite “Instructions to Priests and Temple Officials” stipulate that all sacrificial food and drink must first be offered to the god. Then the priests and their family members consume it on the same day if possible, but if necessary, they may have up to three days (cf. vv. 16–17, which give a two-day limit). Some Hittite food or drink items were permitted only to priests and some was to be consumed within the sacred precincts (as the food in v. 6; 6:16, 26; 24:9). While such Hittite procedures showed important similarities to Israelite ritual practice, the key difference is that Yahweh had no need of food for sustenance.

The animals offered by individuals as purification (“sin”) offerings were specified according to one’s rank within Israelite society. The reparation (“guilt”) offering, brought on account of a violation of someone’s property or an inadvertent break of a covenant stipulation, usually consisted of a ram (or its equivalent in silver shekels), plus a penalty of one-fifth the value of the animal (vv. 1–10; 5:14–19). The sacrificial process included the ritual slaughtering of the animal, the deposition of the drained blood on the altar or its sides, the burning of assigned portions such as the fat and entrails on the large bronze altar, and the setting aside and consumption of priestly portions. In keeping with v. 6; 6:29, only the males among the priests and their families were permitted to consume these “most holy” of offerings.

Besides edible portions, the hide of an animal was valuable and could serve as payment for an officiating priest both in Israelite (v. 8) and Emar (Syria) ritual systems. The Punic Marseilles Tariff not only regulated distribution of dedicated items among priests and offerers; it set monetary fees for some offerings in proportion to the size of the animals.

7:12 expression of thankfulness. Gratitude or a vow (v. 16) could also motivate non-Israelites to make offerings to their deities. For example, the Phoenician king Yehawmilk gave works of art to his goddess to express gratitude for her favor. The Aramean king Bir-Hadad set up a stele “for his lord Melqart, to whom he made a vow and who heard his voice.” Here fulfillment of a votive obligation is also an expression of gratitude.

7:16 vow. See previous note.

7:20 they must be cut off from their people. This terminal penalty for very serious sin (cf. Nu 15:30–31) is administered by God himself and denies the offender an afterlife, most likely through extirpation of his line of descendants. It therefore makes sense that a wrongdoer could be put to death and “cut off” as well (see Lev 20:2–3).

Non-Israelites also referred to loss of posterity as a form of punishment. The Hittite “Instructions to Priests and Temple Officials” warn of the consequences for anyone who neglects to properly extinguish the fire on the hearth, thereby causing the temple to burn down: “He who commits this sin will perish along with his descendants. Of those in the temple none will be left living. They will perish together with their descendants.”

7:30 wave offering. The Hebrew word translated “wave offering” denotes a type of offering that is lifted up toward the heavens in presentation and dedication to God and then lowered into the hands of the priest. This practice is evidenced in Egyptian and Mesopotamian ritual offerings pictured on monuments, steles and plaques. Often the breast or right thigh of the animal was uplifted as a wave offering. In Israel, the wave offering was associated with the peace offering (here; v. 34; 23:20), the consecration of the priests (8:29; Ex 29:27), the dedication of the Levites (Nu 8:11–13, 21), and the purification ritual for Nazirites (Nu 6:19–20).

In Lev 10:15, the thigh of the heave (elevation) offering and the breast of the wave (side to side) offering were ordained as gifts for the Aaronic priesthood. Grain and oil offerings were also presented in such fashion, as with the consecration of the priests (8:27; Ex 29:23–24), cleansing ritual for lepers (Lev 14:12, 21, 24) and the sheaf of grain and two loaves for the Festival of Weeks (23:15, 17). The transference ritual of up and down, forward and backward movement signified that the offering was moving from its temporary owner to its ultimate owner, God.

8:2 Bring Aaron and his sons. Preparing the Israelite sanctuary and its priesthood for their sacred function was an elaborate week-long procedure that purified and sanctified them by ritual agents such as water, anointing oil and sacrificial blood. Non-Israelites also used rituals to consecrate objects and persons. For example, establishing a satellite temple as a new place of worship for the Hittite Goddess of the Night was a seven-day process (five days for the old temple and two days for the new temple) that included purification of new sancta with blood on the last day (see note on 1:5).

All ancient Near Eastern religious systems employed cultic officials of various hierarchical levels to promote positive human interactions with deities by administering and maintaining temples, protecting boundaries of the sacred sphere, performing rituals, seeking to ascertain the divine will through oracles or divination, and leading corporate worship, such as through the performance of festivals. These were weighty responsibilities, so priests at the top of the hierarchy were invested with great power and prestige, and inducting such a person into office often required an elaborate process.

8:10 anointing oil. In order to symbolize divine designation for leadership positions that involved special contracts/covenants with Yahweh, Israelites anointed individuals to change their status to that of priest or king. Elsewhere in the ancient Near East, symbolic anointing of persons could accompany business contracts, marriages, liberations of slaves, and vassal treaties, and they typically represented the obligation and a conditional curse that would take effect if the party that received the oil were to break the treaty. Outside Israel, anointing could also represent elevation of status, including elevation to priesthood.

8:22 ordination. The Hebrew word here is derived from the idiom for “to ordain,” which, translated word-for-word, is “to fill the hand” (see v. 33). The Akkadian cognate expression illuminates the meaning of the idiom: It can refer to authorization for a particular official role, which could be symbolized by filling one’s hand with the relevant tool or insignia, such as a scepter for a king.

9:23 the glory of the LORD appeared. When Aaron and his sons initiated the ritual system by performing their first priestly officiation, Yahweh’s glory appeared, and he consumed the sacrifices with fire to complete his acceptance of the sanctuary. Compare the Sumerian Cylinder B of the ruler Gudea, which describes the initiation festivities for when the god Ningirsu and his consort Baba, as represented by their idols, were settled into their new temple. Their entrance was accompanied by offerings, as well as purification and divination procedures. Gudea presented “housewarming gifts” to the divine couple (cf. Nu 7), prepared a banquet for Ningirsu, and offered animal sacrifices.

10:1 unauthorized fire. Burning incense as an offering to a deity had to be done correctly. Thus, in the daily ritual in the temple of the god Amun-Re at Karnak (Egypt), the high priest was obliged to follow a detailed protocol: reciting spells for striking the fire, taking the censer, placing the incense bowl on the censer arm, putting incense on the flame and advancing to the sacred place. Aaron’s sons had the right idea (incense should be in the air to serve as a screen between the people and the divine presence), but their ritual execution was flawed. The ritual mistake of Aaron’s two sons was burning incense to Yahweh with “unauthorized fire,” which apparently refers to live coals from a fire other than that which God himself had just lit on the altar in the courtyard (9:24; cf. 16:12; Nu 16:46). These coals brought impurity into contact with the divine presence, with dramatic and tragic results—the natural result of impurity coming into contact with God’s presence.

10:6 Do not let your hair become unkempt and do not tear your clothes. Forbidden here (see also 21:10–12) are ancient Near Eastern mourning customs that would have adversely affected the purity status of Aaron and his surviving sons. See note on Nu 14:6.

10:9 You and your sons are not to drink wine. All over the ancient Near East, wine and beer were regularly served to the gods with their sacrificial meals. The idea that deities could become intoxicated by such beverages is reflected in Ugaritic mythology and in the Babylonian epic of creation (Enuma Elish), where partying gods make a momentous decision to exalt Marduk above other gods while they are “under the influence.” There is some evidence in extra-Biblical literature of ritual intoxication among the priests (see also Isa 28:7).

The Hittite “Instructions to Priests and Temple Officials” recognize that drunken priests could cause disturbance or quarreling, or could disrupt a festival. Rather than directly restricting alcohol use, however, these instructions mandate beating as punishment for obnoxious behavior and warn priests that they are accountable for proper performance of festivals, which implies the need for mental clarity.

10:17 eat the sin offering. The purification (“sin”) offering absorbs the impurities that it was presented to remedy. When a great deal is absorbed, the offering is burnt (see note on 4:12), but on most occasions the priest’s eating of the offering is part of the purification process. Aaron’s reluctance to eat the offering may be caused by the presence of the corpses of his sons (v. 2), which add dangerous levels of impurity.

11:2 these are the ones you may eat. From the rather extensive taxonomy of animals in this chapter (cf. Dt 14), a modern reader could gain the impression that meat constituted a substantial portion of the ancient diet. However, such was not the case. Meat was primarily eaten in relation to sacrifices.

There were also restrictions on diet in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, but these were unrelated to each other or to the Biblical ones, and unlike the latter, they did not comprise overall dietary systems. In Egypt restrictions were localized, and generally in each geographic area they dealt with only one species that was prohibited for a religious reason; e.g., it was forbidden to eat a cow where the principal god was Hathor, who takes the form of a bovine (cf. the sacred cow in India). Mesopotamians were supposed to avoid particular activities at certain times, which could include eating some kinds of animals on specific days of the month. They were also to avoid violating taboos, which in some cases could involve eating food reserved for deities.

11:7 the pig . . . is unclean for you. Of all animals in Israel’s environment, only the pig has cloven hooves but does not chew cud. The rules in ch. 11 implicitly single out the pig for exclusion from the holy Israelite diet. Why Israel was not to eat pigs is unclear. Some level of Egyptian society considered pigs unclean. The god Seth injured Horus’s eye, transformed himself into a black pig/boar, and injured it further. The god Re healed the eye and then pronounced the pig an abomination (bwt) for Horus’s sake. This pronouncement explained why, according to the gods, the pig was an abomination to Horus. The concept became a part of Egyptian culture, though pork was eaten in Egypt by at least the lower classes of the land, and it was a staple of the working class at Amarna in the Egyptian New Kingdom. Pigs do not tolerate arid conditions, so Israel would certainly not have herded pigs through the Sinai Desert.

In the ancient Near East the pig was cheap, contemptible and, evidently, not eaten in rituals. Pigs were a part of Hittite rituals that were tied to gods of the netherworld, and they were considered unclean. Thus, sacrificing a pig may be synonymous with sacrificing to demons or the dead. In such a sacrifice, the offerer received none of the meat. Pigs could also be utilized in nonsacrificial rites of purification, including symbolic/magical elimination of impurity or plague (see note on 1:5). A pig could be sacrificed to settle a domestic quarrel. Mesopotamian religion rarely used pigs as food or as sacrifices. In general it was unclean and “not fit for a temple . . . an offense to all the gods.” Pigs, along with dogs, were regarded with contempt in the ancient Near East because of their roles as scavengers. The Hittite “Instructions to Priests and Temple Officials” warn against letting a pig or dog into rooms containing sacred bread. A Mesopotamian saying goes: “The pig is unholy [ . . . ] bespattering his backside, Making the streets smell . . . polluting the houses.”

The pig and wild boar were probably used in Canaanite and/or Syrian rituals, and it is possible that the Israelites did not use them partly because of a connection with these nearby pagan nations. There is no definite evidence in Palestine for a cultic use of pigs in the Bronze Age (3500–1200 BC). In the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000–1550 BC) in Syria and the Holy Land pig remains decrease near cities, especially large cities, but remains are found in rural areas.

Nevertheless, texts and archaeological remains (especially bones) in Egypt and Mesopotamia, as well as Syria-Palestine and North Africa, confirm that pigs were commonly raised for food by non-Israelites. Philistines living on or near coastal areas herded pigs, but the herding and eating of pigs were basically taboo in the highlands of Canaan where Israel settled. The herding and production of pigs actually competed with more productive and profitable agricultural activities. Perhaps this also helps to explain the Biblical prohibition.

11:25 wash their clothes, and they will be unclean till evening. Ablutions with water for ritual purification were also practiced outside Israel. In a Sumerian inscription, Gudea prepares to offer a sacrifice by bathing before dressing. While the concept of evening-ending impurity appears to be unique to Israel, a Ugaritic text views sunset as a boundary for another ritual category: “At the descent of the sun, the day is profane. At the setting of the sun, the king is profane.”

12:2 ceremonially unclean for seven days. Throughout history, many cultures all over the world have treated genital discharges, including those involved in menstruation and childbirth, as causing ritual impurity (see notes on ch. 15). A Hittite birth ritual text requires a sacrifice on the seventh day after birth and says that a male infant is pure by the age of three months, but a female is pure at four months. As in ch. 12, there is a weeklong initial period of impurity, and purification of a girl takes longer (cf. vv. 4–5). One possible reason why a daughter requires a longer time for purification is that a daughter often has a slight vaginal discharge at birth, making both mother and daughter unclean. We can observe that whereas the Hittite process has to do with the baby’s impurity, Leviticus is concerned with that of the mother. Also, the Hittite sacrifice is offered at the end of the first week, but Israelite sacrifices come after the entire period of purification.

12:7 atonement. See note on 1:4. This case makes it clear that the “sin offering” is more accurately a purification ritual, since no sin is involved here.

13:2 a defiling skin disease. A more descriptive rendering is “a scaly skin condition.” Here the issue regarding a scaly (with lesions) skin disease is not infection/contagion in the sense that it would make other people physically sick. Rather, the concern is with protection of the sphere of holiness, centered at the sanctuary, from defilement by ritual impurity.

The maladies lumped in chs. 13–14 under the heading of scale disease cannot be simply equated with modern “leprosy” (i.e., Hansen’s disease). The Hebrew term applies to a complex of conditions, including some that resemble psoriasis and vitiligo, just as Hippocrates used Greek lepra for several skin diseases (see note on Ex 4:6). In Leviticus, scale disease is not restricted to just human beings, but could also affect a house (see note on Lev 14:34). In some instances, white discoloration of skin or hair could be a factor among others that was symptomatic of the impure affliction. For a similar dim view of white discolorations, compare Mesopotamian omens. Hansen’s disease was little known in the ancient Near East prior to the time of Alexander, though there is one Assyrian medical text that describes symptoms that may well be Hansen’s disease.

13:46 they must live outside the camp. Some Mesopotamian curses also speak of ostracizing persons afflicted with scale disease (see previous note). Compare the Babylonian rule in which cultic functionaries who became ritually impure by purging the Ezida cella of the god Nabu on the fifth day of the Babylonian New Year Festival of Spring were required to remain outside the city of Babylon for the duration of the festival.

14:4 two live clean birds. This elimination ritual symbolically transfers ritual impurity from the recovered person to the living bird by means of the blood of the (other) slain bird, in which (along with water) the living bird is dipped. Then the living bird is set free and carries the impurity away. Birds were also used in Anatolian and Mesopotamian elimination rituals. A Hittite ritual to remove evil mandates the dispatch of a goat (cf. 16:21–22) and the release of an eagle and a hawk.

In a Mesopotamian namburbi ritual to get rid of evil portended by a bird (in an omen), a male and female partridge are obtained. The patient raises them with his hands and recites an incantation before the sun-god Shamash that includes a request that the evil be distanced from the patient. Upon completion of the rite, the male bird is released to the east, before the sun-god. Unlike the Biblical ritual, the freed bird does not receive a transfer of impurity, but by its physical form represents the evil (cf. Nu 21:6–9).

14:5 fresh water. Hittites and Babylonians also regarded fresh flowing water, such as rivers, as superior sources for purification. On the fourth day of the Ninth Year Festival of Telipinu, Hittites would take images of Telipinu and other gods, plus a cult pedestal, to a river and wash them. During the Babylonian New Year Festival, the high priest is to bathe in water from the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers (see note on 16:4).

14:34 a spreading mold in a house. In Mesopotamia, fungus in the walls of a house could be a good or bad omen. Black fungus portended brisk trade and wealth at that address, but green and red fungi (cf. v. 37) were ominous: “The master of the house will die, dispersal of the man’s house.” By contrast, while fungus in an Israelite house could generate the need to replace some of its material and ritually purify it—or (in a worst case scenario) could lead to its condemnation and demolition—the problem was limited to the structure of the house (as opposed to something in it) and did not indicate other kinds of dangers for future inhabitants.

In contrast, an Anatolian ritual invokes underworld deities to come up, take evils (impurity, perjury, bloodshed, curse, threat, tears, sin, quarrel and/or gossip) haunting a house and transport them back down into the nether regions. At the end of the process, safe disposal of the ritual paraphernalia takes place out in the steppe country. In terms of the nature of evils remedied, deities involved and procedures implemented, the Anatolian ritual differs greatly from Israelite purification of a fungous house. However, there are some strikingly specific points of contact: use of water (“water of cleansing”—cf. Nu 8:7; 19:9; spring water—cf. Lev 14:51), the number seven (drawing water and pouring it out; cf. seven days in vv. 38–39), red wool (cf. v. 49), contact of a slain animal with water (but libating a lamb before slaughtering it, unlike v. 50), and slaughter of birds (but cooked for sacrifice, unlike vv. 50–52).

15:2 an unusual bodily discharge. The male impurity stems from an abnormal urethral discharge that could consist of pus or excessive mucus and which could be caused by gonorrhea or infectious urinary bilharzia, an ailment known to have been a problem in antiquity. The abnormal female condition in vv. 25–30 has to do with a chronic vaginal discharge of blood, which arises from a disorder of the uterus.

15:10 whoever touches any of the things that were under him will be unclean. A discharge from the genitals directly contaminated objects underneath, such as a bed or chair, which would secondarily contaminate anyone else who touched them. A Mesopotamian incantation also speaks of secondary contamination by sleeping on the bed, sitting in the chair, eating at the table, or drinking from the cup of an accursed person.

15:16 emission of semen. A Mesopotamian omen says: “If a man ejaculates in his dream and is spattered with his semen—that man will find riches; he will have financial gain.” But in the Israelite religious system, any seminal discharge, including nocturnal emission (Dt 23:11), generated ritual impurity. Nevertheless, this impurity simply disqualified a person from coming in contact with holy things. There was no acknowledgment of the belief held by some ancient people (such as Hittites) that nocturnal emissions indicated sexual relations with spirits, even with deceased family members.

An Israelite who engaged in sexual relations was barred from entering the sacred precincts of the sanctuary until evening. The situation was similar for Egyptians, but differed in other religious cultures, where ritualized sex flourished. The Hittite “Instructions to Priests and Temple Officials” prohibit cultic functionaries from defiling sancta (on pain of death for a kind of intentional violation; cf. Lev 22:9) by approaching sacrificial loaves and libation vessels without bathing after sexual intercourse, but that is all. There is no waiting period and no prohibition of sexual activity elsewhere in the temple precincts.

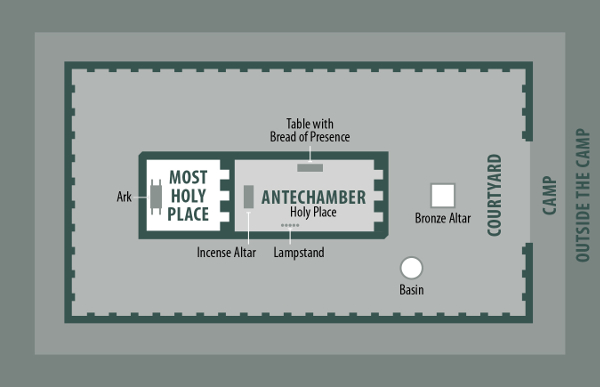

16:2 into the Most Holy Place. By contrast to the Israelite high priest, who was permitted to enter the inner apartment of the sanctuary only once per year, other ancient Near Eastern priests were required to enter the inner sanctums of their temples every day in order to care for and “feed” (images of) their gods. Even such daily access was restricted to authorized persons. Ancient Near Eastern temples were not places of public worship like our churches or synagogues today because they were regarded as possessing or containing sanctity that had to be guarded against profanation or defilement (see note on Nu 18:1). behind the curtain. The Israelite sanctuary had three curtains: a screen (Hebrew masak) at the entrance to the court, another screen (also called a masak) at the entrance to the outer sanctum, and an inner curtain (Hebrew paroket; see the article “The Tabernacle”). In this verse the Hebrew word is paroket, which only denotes the curtain that formed the boundary of the inner sanctum by separating the two apartments of the tabernacle. This special usage agrees with the fact that the Akkadian cognate parakku refers to a defined sacred space around the presence of a deity (or divine symbol/image). The Israelite sanctuary was not unique in having such a curtain; a Mesopotamian omen refers to “the linen curtain of a temple (in front of the cult statue).” The function of such curtains was to shield the sacred image (or in Israel, the ark) from profane visibility. atonement cover. The Hebrew (kapporet) is also translated “mercy seat,” but all translations are speculative. The term refers to the solid plate or sheet on top of the ark, described in Ex 25:17. One suggestion is that kapporet comes from an Egyptian cognate, which refers to a place to rest one’s feet. Since the ark is seen as a footstool for God (see 1Ch 28:2), this would fit well.

16:4 he must bathe himself with water. Non-Israelites also purified themselves with water before engaging in ritual activity. In a Sumerian inscription, the ruler Gudea prepares to offer a sacrifice to his god Ningirsu by bathing before dressing. In Babylon, during the New Year Festival of Spring (= Akitu Festival), the high priest was to do the following: “On the 5th day of the month Nisannu, during the final four hours of the night, the High Priest arises and bathes in the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.” By washing with water from these special sources, which also provided water for later sprinkling the temple to remove ritual impurity, the high priest attained a degree of ritual purity necessary for subsequent officiation, which involved entering the presence of the high god Bel (= Marduk) and his consort (see note on 22:3–9).

16:10 making atonement by sending it into the wilderness as a scapegoat. Azazel’s nonsacrificial “tote” goat (NIV “scapegoat”) served as a ritual “garbage truck” to purge the Israelite community of desecration through a process of transfer and disposal of impurity from the sanctuary. Other ancient Near Eastern rituals included transfer and disposal. The Hittite Ambazzi and Huwarlu rituals closely parallel the Israelite ritual in that they used live animals as bearers of the evil and lack the motif of substitution. The “Ritual of Ambazzi” to rid people of “evil sickness” and “evil tension” goes as follows:

• Wraps some tin a on a bowstring

• Puts it against right foot and right hand of participant

• Puts the tin on a mouse

• Incantation to indicate transfer of offense

• Mouse charged to carry offense far away

• God to drive mouse away

• Goat is promised to god as meal

• Offerings then presented

Unlike the Biblical ritual, in this description a deity is entreated (by words and sacrifice) for help in getting rid of the animal bearing the evil.

16:14 take some of the bull’s blood. On the Day of Atonement, the high priest purged (Hebrew kipper—usually rendered “atone”) the three major consecrated components of the sanctuary—the inner sanctum, outer sanctum and outer altar—on behalf of the priests and nonpriests by applying blood of special purification (“sin”) offerings (bull and goat), to parts of them (see vv. 14–19, 20, 33).

Non-Israelite peoples also periodically cleansed their sacred precincts and/or sacred objects contained in them, but they generally used substances other than blood (see note on 1:5). The Sumerian Nanshe Hymn mentions purification of the temple belonging to the goddess Nanshe: “her house Sirara where water is sprinkled.” On the fourth day of the Hittite Ninth Year Festival of Telipinu, images of several deities (including the god Telipinu) and a cult pedestal were ceremonially transported on a cart from Telipinu’s temple to a river, in which they were washed.

Like purgation of the Israelite sanctuary, purification of the Babylonian temple precincts on the fifth day of the New Year (or Akitu) Festival of Spring was also a three-stage process: purgation of the god Marduk’s great Esagila temple complex as a whole by sprinkling water, sounding a copper bell, and carrying around a censer and torch inside the temple; this was followed by two purifications of the Ezida guest cella of the god Nabu. The first purification of the Ezida included not only sprinkling holy water and carrying a censer and torch, but also smearing the doors with cedar oil and wiping (Akkadian kuppuru, cognate to Hebrew kipper) the cella with the decapitated carcass of a ram. The second purification of the Ezida involved setting up a kind of canopy called “the Golden Heaven” and reciting an incantation calling on the gods to exorcise demons from the temple (see note on v. 10).

Notice that whereas the Israelite sanctuary was cleansed from physical ritual impurities and moral faults caused by the people throughout the year (v. 16), the goal of purging Babylonian holy places was to remove impurity caused by the presence of demons. It was not unusual in the ancient Near East to have elimination rites similar to the Israelite Day of Atonement. Other ancient peoples sometimes used blood and sometimes used an animal to carry away the impurity or offense.

16:26, 28 must wash his clothes and bathe himself with water. The need for this purification implies that such an assistant was contaminated by contact with the purification (“sin”) offering carcasses, which had indirectly absorbed evils as ritual “sponges” when blood from the same animals was directly applied to the sanctuary. Somewhat similarly, Babylonian functionaries slaughtered a ram, directly wiped (kuppuru) Nabu’s Ezida shrine with the carcass to absorb impurity (cf. previous note) and disposed of the ritual “sponge,” consisting of the ram’s body, by throwing it and the ram’s head in the river. Consequently, these functionaries became ritually impure, as indicated by the fact that they were required to remain outside Babylon for the remainder of the New Year Festival of Spring, i.e., from days 5 to 12 of the month Nisannu.

16:29 On the tenth day of the seventh month you must deny yourselves. Once a year on the Day of Atonement, all Israelites were to physically deny themselves by fasting and participating in related customs, such as wearing sackcloth (cf. Ezr 8:21; Ps 35:13; Isa 58:3, 5), and to abstain from work (see Lev 16:31). In these ways they would demonstrate their humble loyalty to the Lord at the time when his sanctuary was purged of their impurities and sins. If they willfully neglected to participate in the practice of self-denial or to keep Sabbath on this day, he would reject and terminally punish them (23:29–30). In that sense, the Day of Atonement was Israel’s judgment day. Notice that every fiftieth year, the Day of Atonement marked New Year’s Day for the beginning of the Jubilee Year (25:9–13), which brought judgment in the additional sense of legal deliverance from negative effects of insolvency.

Written centuries before Leviticus, the Sumerian Nanshe Hymn (c. 2100–2000 BC) also expresses the concept that human beings would be annually judged by their deity. The hymn describes a New Year celebration at which the goddess Nanshe is portrayed as holding a yearly review of persons economically dependent on her temple. Depending on whether they were faithful in observing her ritual and ethical standards throughout the year and in coming to her temple to participate at the New Year, she would renew or terminate their contracts.

17:3–4 Domestic animals suitable for sacrifice could only be slaughtered in the tabernacle. This prohibition would prevent the sacrifice of these animals to other gods or as appeasement to underworld deities. The crime here is participation in illicit rituals.

17:7 goat idols. These goat idols (Hebrew sheirim) appear to be objects of worship, receiving sacrifices, which would make them unlike any demons in Mesopotamia (which do not have any associated temples, cult or priests and do not receive sacrifices). Though it is not uncommon to translate the term “goat-gods” or “satyrs,” there is no indication that these are composite creatures. The word occurs many other times to refer simply to domesticated goats. The case cannot be made that we must consider these to be “demons” just because they fit into what we see in the ancient Near East; they most definitively do not, for not a single aspect matches up with demons from Mesopotamia. They are being treated in the category of gods even though the sacrifices they receive are illegitimate, which puts them in the same category as foreign gods. Given the connections between goats, uninhabited country, demons, and the underworld, we can better understand why ch. 17 would emphasize proper use of blood on the Lord’s altar.

18:6 Genesis recounts incest between Lot and his daughters (Ge 19:30–38) and between Reuben and Bilhah, his father’s concubine (Ge 35:22; 49:4). Incest was common in families of Egyptian pharaohs for the purpose of concentrating power. In ancient Persia, marriages of men to their sisters, daughters or even mothers were regarded as acts of piety. However, most ancient societies discouraged incest. The Babylonian Code of Hammurapi and the Hittite laws viewed some sexual liaisons in ways that are paralleled in Lev 18; 20 (see the article “Sanctioned Relationships in the Ancient Near East”).

18:22 There is plenty of evidence for homosexuality and bestiality in the ancient Near East. A Mesopotamian omen (concerned with results rather than morality) prognosticates: “If a man has anal sex with a man of equal status—that man will be foremost among his brothers and colleagues.” However, the Middle Assyrian laws have a different attitude, which is closer to that of Leviticus: “If a man sodomizes his comrade and they prove the charges against him and find him guilty, they shall sodomize him and they shall turn him into a eunuch.” In harmony with this negative assessment, a confession of righteousness in the Egyptian “Book of the Dead” affirms: “I have not copulated with a boy.” Both homosexuality and bestiality were practiced in the context of ritual or magic in the ancient Near East. The latter particularly occurred in Ugarit, but was banned in Hittite laws (see note on v. 23).

18:23 Do not have sexual relations with an animal. Unlike the Bible, Ugaritic mythology describes bestiality by deities. When the deity Motu threatens Balu (Baal) with death, the latter seeks to guarantee himself a form of afterlife through progeny by repeatedly copulating with a cow, which conceives and bears him a son. This is not so surprising because mixed beings were common in the realm of the gods (see notes on 19:19; Eze 1:5, 10) throughout the ancient Near East.

The Hittite laws condemn to death a person who engages in bestiality with certain kinds of animals (a cow, sheep, pig, dog) unless the king grants him mercy, which may also be extended to the animal. Even if the monarch hears his case, the offender may not personally appear before him lest the king be (secondarily) defiled.

19:2 Be holy because I, the LORD your God, am holy. The Egyptian “Instruction of Amenemope” presents the divine standard as unattainable for human beings as it contrasts the perfection of God as over against human failures. The Law (Torah) provides the Israelites with instructions that will enable them to live in close proximity to a holy God and to preserve the purity and sanctity of sacred space. They have been conferred a holy status and are expected to conduct themselves in a way that is fitting to that status. They are able to meet these requirements, though it is not easy. The instructions also provide a means by which failures can be addressed so that God can remain present among them. Compare the Sumerian Nanshe Hymn, according to which temple dependents are judged by their faithfulness (or lack thereof) to the personal cultic and ethical standards of the goddess.

19:4 Do not turn to idols. Ancient Near Eastern peoples regarded their deities as powerful living beings, but they worshiped gods through idols identified with them, which were believed to somehow partake of and reflect the divine essence (see note on Ex 20:4).

19:10 In fertility cults the portion left would have been an offering to the gods of the ground; here it becomes a means to care for the poor (see Ru 2). Texts from Nuzi suggest a similar practice among the Hurrians.

19:15 Do not pervert justice. Throughout the ancient Near East, justice was a high priority and rulers prided themselves on carrying out their god-given responsibility to protect weaker members of society from oppression (cf. Ex 22:22). The Sumerian king Uruinimgina of Lagash (c. 2351–2342 BC) appears to have pioneered a long tradition of social justice in the ancient Near East by establishing the first-known systematic legal reforms. Later laws and hymns echoed the ideals that Uruinimgina expressed as follows: “A citizen of Lagash living in debt, (or) who had been condemned to its prison for impost, hunger, robbery, (or) murder—their freedom he established. Uruinimgina made a compact with the divine Nin-Girsu that the powerful man would not oppress the orphan (or) widow.” Human justice and mercy were thought to reflect attributes of divinities, such as the sun-god (Šamaš/Utu), who was the patron of justice. Although at this point in their history Israel had no royal mediator (see note on Dt 5:27), they were still expected to reflect their deity’s attributes of justice and mercy in their society.

19:16 Do not go about spreading slander. Ancient Near Eastern texts similarly discourage slander of various kinds. The Egyptian “Instruction of Amenemope” admonishes: “Guard your tongue from harmful speech, / Then you will be loved by others . . . / Do not shout “crime” against a man, / When the cause of (his) flight is hidden.” In an Old Aramaic inscription, King Panammuwa boasts that he did away with war and slander (lit. “sword and tongue”) from his father’s house. At Nuzi, the penalty for slander was payment of one ox. In the Middle Assyrian Laws, a man who goes around spreading baseless rumors or falsely claims in a public quarrel that someone sodomized another man is punished with 50 blows, service to the king, a humiliating haircut and a fine of 3,600 shekels of lead.

19:18 love your neighbor as yourself. Such an attitude is illustrated by the covenanted love between David and Jonathan, who “loved [David] as himself” (1Sa 18:3). Similar loyal love is described in a treaty between the Hittite king Tudhaliya IV and Kurunta of Tarhuntassa. Lev 19:34 extends the command to demonstrate such love to the resident alien, who is to be treated like a native citizen. Similarly, a Mesopotamian treaty text from Alalakh provides that “[if people of my land] enter your land to preserve themselves from starvation, you must protect them and you must feed them like (citizens of) your land.” In these sorts of examples it can be seen that “love” does not refer to an emotion or sentiment, but to service, consideration and preferential treatment.

19:19 Do not mate different kinds of animals. In ancient Near Eastern art and literature, mixed beings are prevalent in the superhuman sphere of gods and demons (cf. Eze 1:5–11; see note on Lev 18:23). In Mesopotamia, demons, monsters and minor protective deities were depicted as bulls and lions with human heads, lion-centaurs, snake-dragons, goat-fish, bird-men, scorpion-people, and so on. two kinds of seed. In Israel mixtures belonged to the sacred realm: the yield resulting from planting two kinds of seed in a vineyard would become holy and therefore forfeited to sacred ownership by the sanctuary (Dt 22:9). two kinds of material. In Israel fabric of mixed wool and linen was reserved for parts of the tabernacle, high priest’s garments, and belts of ordinary priests (Ex 26:1, 31; 28:6, 15; 39:29).

19:20 not to be put to death, because she had not been freed. The violation does not call for the death penalty, as it would if the woman possessed the power of consent belonging to a free woman (Dt 22:23–24), provided that an inquest confirms her status, along with determining the amount of compensation due to her owner (Lev 6:4–5). Compare the Mesopotamian Laws of Ur-Nammu and Laws of Eshnunna, according to which a man who deflowers a slave woman must pay her owner.

19:26 Do not eat any meat with the blood still in it. This idea carries the more precise sense of “You shall not eat over the blood.” This is not simply a reiteration of the command to abstain from eating meat (not including fish) from which the blood is not drained out at the time of slaughter (17:10–14; cf. Ge 9:4; Ac 15:20, 29). The prohibition in this verse appears related to the rest of the same verse, which forbids various kinds of divination (not including “sorcery”). Because we know that some ancient peoples poured blood into the ground as libations to underworld deities (see notes on Lev 1:5; 17:7), the prohibition of eating over the blood was presumably designed to prevent Israelites from associating with some pagan practice, such as a form of divination that consulted ancestral spirits (cf. vv. 27–28; Dt 14:1–2; Jer 48:37; Eze 33:25; see the article “Balaam”).

19:28 Do not cut your bodies for the dead. Lacerating oneself in mourning was a heightened expression of sorrow (Jer 16:6; 41:5). In the Ugaritic Baal Cycle, when the chief god Ilu (El) learns that Balu (Baal) is dead, he goes into paroxysms of grief that emphasize the magnitude of the catastrophe: “He pours dirt of mourning on his head, dust of humiliation on his cranium, for clothing, he is covered with a girded garment. With a stone he scratches incisions on (his) skin, with a razor he cuts cheeks and chin. He harrows his upper arms, plows (his) chest like a garden, harrows (his) back like a (garden in a) valley.” In the Aqhat Legend professional mourners cut or possibly bruise their skin. An Akkadian text from Ugarit describes persons who lacerate themselves on behalf of a dying righteous person. tattoo marks. Unlike the first part of the verse, tattoos are not associated with mourning rites. The use of tattoos is evidenced from early in the Biblical period. Some Egyptian mummies display them. Many simply feature geometric patterns but some have portrayals of gods or are the names of gods. They were at times used to mark someone’s loyalty to a particular god. In Mesopotamia most known tattoos are slave markings, though there are also known examples of priests receiving marks to designate the god they serve. It can therefore be concluded that tattoos are likely banned not just because of what they do to the body, but because of what they communicate about a relationship to deity.

19:35 Do not use dishonest standards. Honesty through use of standard weights and measures was a common topic in ancient Near Eastern literature. In the Egyptian “Book of the Dead,” an Egyptian claims innocence: “I have not added to the weight of the balance. I have not tampered with the plummet of the scales.” The Code of Hammurapi requires standardization for repayment of debts and for purchases. The Egyptian “Instruction of Amenemope” provides a reminder of accountability to divine power: “Do not move the scales nor alter the weights, / Nor diminish the fractions of the measure . . . / Do not make for yourself deficient weights, / They are rich in grief through the might of god.”

20:2 sacrifices . . . his children to Molek. It is possible, or even likely, that this refers to human sacrifice (for some qualifications, see notes on Ge 22:2; Dt 12:30), which involved passing one’s child through fire as part of Syro-Palestinian worship of the underworld god Molek. In addition to terminally condemning anyone who engages in this practice, ch. 20 condemns anyone who tolerates a Molek worshiper.

21:1 A priest must not make himself ceremonially unclean. Uncleanness was not always avoidable, and often the cause of uncleanness was not something that would be considered sinful, including sexual or disease-related impurities, or impurity resulting from contact with a corpse. Although a matter of etiquette rather than ethics, the purpose of this mandate was to protect the sanctuary and those who officiated in it from that which was inappropriate. Ancient Near Eastern priests were also required to be ritually pure—through avoiding impurities or undergoing purification rituals—before approaching their deities.

21:7 defiled by prostitution. Implies flagrant, repeated offenses. divorced. The priest was denied the right to marry a divorced woman, most likely because the principal charge against a woman in a divorce was infidelity.

21:17 none . . . who has a defect may come near to offer. Respect for the deity required that his priestly servants be free from physical defects, just as animals offered to him were not to be defective (22:17–25). This includes birth defects and disfiguration caused by accident or disease. Hittite ritual rules also excluded persons with physical disabilities from intimate access to deity in sacred precincts. Even though he could not approach the altar, the disabled priest in these cultures was still allowed his share of the priestly portion of the sacrifice.

22:3–9 The altar and those who served it were required to maintain strict purity and cleanness. One Hittite text contains a long list of instructions for maintaining ritual purity and cleansing the priest or temple in the case of contamination, which is similar to that found in ch. 22, but adds the prohibition that anyone who has had sexual relations with a horse or mule could not become a priest, specifying an additional means to acquire uncleanness.

22:21 it must be without defect or blemish to be acceptable. Following the same principle centuries earlier, Gudea of Lagash sacrificed to his god Ningirsu, “properly arranging perfect ox and perfect he-goat.” Cheating the Lord by sacrificing defective animals (except for some defects allowed in freewill offerings, see v. 23) was forbidden (cf. Mal 1:6–14). This ruled out the substitution of defective animals for acceptable ones previously designated as sacrifices. Like Malachi, the Hittite “Instructions to Priests and Temple Officials” warn that the deity holds people accountable for such cheating.

22:28 The regulation that a mother and her young not be offered on the same day provided some protection to those with just a few animals who might otherwise have been forced to decimate their herds.

23:24 On the first day of the seventh month. The first month of the Israelite calendar is Nisan in the spring (see Ex 12:2). However, in post-Biblical tradition the first day of the seventh month (Tishri) has become Rosh Hashanah (“New Year”). This is not a contradiction. In antiquity, a group of people could have more than one New Year’s Day to mark half years that commenced with events such as equinoxes, or to initiate different kinds of full years that overlapped each other (cf. a modern-day fiscal year beginning July 1). Once Jewish tradition came to regard the first day of the seventh month as New Year’s Day, it was a short step to view it, along with the Day of Atonement, as a day of judgment (see, e.g., in the Mishnah see Rosh Hashanah 1:2) in harmony with ancient Near Eastern traditions that placed judgment in the framework of New Year celebrations (see note on 16:29).

24:8 Sabbath after Sabbath . . . as a lasting covenant. Compare Ex 31:16, where Sabbath signifies a “lasting covenant” between the Lord and the Israelites, whom he makes holy (Ex 31:13), because God created the heavens and earth and rested on the seventh day, a day he made holy (Ex 31:17; see Ge 1–2). A Syrian amulet bears a Phoenician inscription that expresses some parallel motifs: “Ashur has made an eternal covenant with us. He has made (a covenant) with us, along with all the sons of ’El and the leaders of the council of all the Holy Ones, with a covenant of the Heavens and Eternal Earth, with an oath of Bal.”

24:11 blasphemed the Name with a curse. In the ancient Near East, deities and their names were regarded as holy. The Egyptian “Great Hymn to Osiris” praises the god: “Holy and splendid is his name.” Speaking evil of a deity or blaspheming his/her name (cf. Ex 22:28) was a serious offense, as shown by harsh Assyrian punishments on blasphemers, including cutting their tongues and having them skinned alive. In a Syrian treaty between Ebla and Abarsal, one who committed treason by blaspheming his own king, gods and country could be put to death. A negative confession in the Egyptian “Book of the Dead” declares, “I have not reviled a god . . . I have not cursed a god.”

24:14 stone him. In the Bible, stoning is a common way for the community to execute someone guilty of a crime against it, perhaps so that no one individual would be responsible for the death of the offender. Outside the Bible, various modes of execution are attested (e.g., drowning, impaling and burning); stoning is present in some non-Israelite texts, such as the Syrian “Hadad Inscription,” but it is rare.

24:17 Outside Israel, a person who committed homicide could receive capital punishment, as in the Mesopotamian Laws of Ur-Nammu. Alternatively, he could be forced to give up one or more persons who belonged to him (Hittite Laws). If a death occurred during a brawl, the penalty was a monetary fine (Laws of Eshnunna, Code of Hammurapi). According to the Hittite king Telipinu, it was up to the heir of a murdered person to decide whether the murderer would die or pay. The death penalty for those who committed intentional homicide seems uniformly allowed in the ancient Near East. However, the death penalty was not usually mandatory; it simply represented the fullest extent of the law. Convicted murderers could, in some cases, make a payment that functioned as a ransom for their life. The text of one Neo-Assyrian document states that the perpetrator will, instead of making a monetary payment, give a person (perhaps from his household) to the son of the victim. Here, the ransom takes the place of the death penalty. In Israel, on the other hand, a person who takes the life of another forfeits his own right to live, and there is no alternative to capital punishment.

24:18 make restitution. Law collections outside the Bible present similar remedies. For death of an animal or such serious injury to an ox that it is unusable, the Code of Hammurapi stipulates replacement with an animal of comparable value. For other permanent injuries, money payments suffice. The Hittite Laws mandate money payments for death or permanent injuries to animals.

24:20 eye for eye. The principle of “an eye for an eye” also shows up in the Code of Hammurapi. This type of punishment, which tries to mirror the injury committed, is known as talionic retribution, and it constituted a basic principle of ancient Near Eastern law. Part of its purpose was to deter potential wrongdoers and to ensure that they would be punished appropriately. Another purpose, though, was to ensure that punishments did not go too far. If a man gouges out the eye of another, his eye can be gouged out, but his ear cannot also be cut off. The system may still seem cruel to modern readers, but this was one way in the ancient world to put limits on punishment. In their time, retaliatory punishments administered by civil courts were a major advance for the cause of justice, in that they curbed unlimited retribution and ensured that rich and poor were treated in a way that affected them equally.

These talionic penalties thus constituted for ancient Near Eastern legal systems the maximum penalty for a given crime. It was also possible for lesser punishments to be imposed. For instance, in the Law of Eshnunna, the penalty for the loss of an eye does not call for the assailant’s eye to be put out; rather, it stipulates a 60-shekel fine. It is probable that most, if not all, ancient Near Eastern societies allowed for such lesser penalties (usually monetary fines). Statements like “eye for eye” thus declare the most severe punishment allowed by law.

25:2 the land itself must observe a sabbath. This concept will be most clearly understood when we recognize that the issue of “rest” in the Bible does not have “relaxation” as its focus. It is more basically involved with recognition that God is the source and center of order, and that he, not our own effort, is the one who provides to satisfy our needs. The land sabbatical enforces the same point, since God is the one who is responsible for the fertility of the fields. For that reason, the Israelites are still allowed to eat “whatever the land yields” (v. 6)—i.e., what God provides in growth.

The practical benefit derived from resting the land is the preservation of the soil’s fertility; large areas of Mesopotamia were abandoned due to high sodium levels in the soil caused by irrigation. Ugaritic texts also feature a seven-year agricultural calendar that allowed portions of the field to “rest” each year (a practice we now call “crop rotation”).

25:10 liberty. The Hebrew word here is deror (see also Isa 61:1; Jer 34:8). It is related to the Akkadian word anduraru, which refers to various kinds of release, including remission of commercial debts and manumission of private slaves. Especially near the beginnings of their reigns, several Mesopotamian kings proclaimed releases similar to the Biblical Jubilee, in that they provided relief for debtors and return of land and persons pledged, sold, or enslaved in direct consequence of debt. The purpose of such legislation was to restore some economic and social equilibrium. The main unique feature of the Israelite Jubilee release was its regular recurrence, which gave it predictability and independence from the arbitrary will of an absolute human ruler. Also, whereas exceptions to releases in Mesopotamia could be specified by royal edicts or by contracts, the Israelite Jubilee was designed to benefit all Israelites (but not non-Israelites, vv. 44–46). to your family property and to your own clan. Basic to the Israelite economic system was the concept that God was the ultimate owner of all land and granted to each family an inalienable right to use (but not permanently sell) a piece of agricultural real estate. This right was based on the premise of the covenant land grant. Some Ugaritic real estate documents show similar concern for permanence of land grants, though not on the basis of a covenant relationship with a god. In Egypt, the pharaoh, who was regarded as divine, was the overall owner of land and assigned it to his subjects. Whatever the situation for commoners may have been in actual practice, an Egyptian treatise on kingship recognized the ideal of free people with use of their own land; such people were more likely to be contented, unified and loyal than they would have been had their situation been otherwise. Unlike Israel and Egypt, Mesopotamia lacked a unified system of land ownership.

25:25 their nearest relative is to come and redeem what they have sold. The Laws of Eshnunna contain the provision: “If a man becomes impoverished and then sells his house, whenever the buyer offers it for sale, the owner of the house shall have the right to redeem it.” Lev 25 provides a higher level of protection for the original owner: an Israelite can redeem his ancestral property anytime, not just when the other party decides to put it up for sale, and even if he is unable to redeem it, his kinsman should step in to keep the property in the extended family (cf. Ru 4:1–12; Jer 32:6–15).

25:36 Do not take interest or any profit from them. Agreements to pay interest were common in the ancient Near East, but the need to prevent exploitation was well recognized. The Code of Hammurapi limits the amount of interest that can be charged and cancels interest payments for any year in which a farmer’s crop is devastated by an “act of god” (storm, flood, drought). So, as in Israelite law, a creditor was to show mercy to (rather than receive profit from) an individual beset by unfortunate circumstances.

25:39 fellow Israelites . . . sell themselves. If an Israelite farmer fell on hard times, he would have no way to support himself and could be forced into slavery, along with his family members, whether by selling himself (and them) or by being seized as collateral for a debt in default. Other ancient Near Easterners could fall into slavery for similar reasons, as well as through defeat in warfare (Dt 20:10–11; 2Sa 12:31).

In Babylonia, debt-slaves were theoretically to be kept in bondage until the debt had been worked off. In practice, however, unless they were redeemed, they remained in the possession of the creditor as long as they lived. The Code of Hammurapi remedied this grim scenario by limiting the service of a wife and children to three years. Ex 21 and Dt 15 went further, extending amnesty to the debtor himself and limiting service to six years, regardless of the size of the debt. Lev 25 adds crucial elements: An insolvent Israelite forced to sell his land is to be treated as a hired worker, and release of such servants is coordinated with release of their land, which is essential for their independent survival. When the man was finally able to repay the debt, along with any interest charges, he could redeem his family member(s) from slavery. If he sold himself into slavery, a relative, such as a brother, might try to redeem him. Redemption of persons was also practiced in Mesopotamia.