Annotations for 2 Chronicles

1:1 the LORD his God was with him. The notions of divine election, divine presence and divine enablement concerning kings are seen in a number of ancient Near Eastern texts. For example, the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose IV (fifteenth century BC) is assured by his god Harmakhis-Khepri-Re-Atum that “I am with thee; I am thy guide.” Similarly, the Hittite king Muwattalli (c. fifteenth century BC) refers to himself as the “Beloved of the Storm-god.” In addition, the twenty-second-century BC Sumerian king Gudea notes that the god Ningirsu set him “firm upon his throne.” Likewise, the Neo-Babylonian king Nabopolassar (seventh century BC) notes that he was called by Shazu (= Marduk) to be lord over the country and to be successful in everything he did. Similarly, Nabopolassar’s son Nebuchadnezzar is noted as being “permanently selected by Marduk.” All of this underscores the importance that the favor of the deity be understood as resting upon the ruler. They demonstrate that culturally, God interacted with Israel in terms that were familiar to them. These are the sorts of promises that gods typically made to kings in the ancient world.

1:3 the high place at Gibeon. High places are religious sites typically associated with hills or mountains—the added elevation providing a sense of closeness to the supernatural realm. High places were used in conjunction with the worship of a number of gods and had a variety of forms (roofs, open air, platforms, stairs, podiums, etc.), sizes (recall that the high place in the district of Zuph accommodated Samuel, Saul and 30 or so other guests, 1Sa 9:22) and functions. Prior to the construction of the temple, high places in Israel were simply generic places where worship or cultic activity took place, reflecting a noncentralized worship context. Following the completion of the temple, however, high places became associated with idolatry and syncretism. Consequently, the removal or nonremoval of high places became a litmus test for the religious fidelity of a given king. With this in mind, much is done within the context of Chronicles to show that the high place at Gibeon was a legitimate place of worship. Earlier the Chronicler noted that David appointed Zadok the priest to serve “before the tabernacle . . . at the high place in Gibeon” and to present burnt offerings on the bronze altar “in accordance with everything written in the Law of the LORD” (1Ch 16:39–40). We learn in the present context (2Ch 1:5) that, along with the tabernacle made by Moses, the bronze altar crafted by Bezalel, was also at Gibeon. The tabernacle underscores continuity with the Mosaic tradition, while the bronze altar connects the site with the Aaronic priesthood. All these details together stress that Gibeon was a legitimate sacred place.

1:7 That night God appeared to Solomon. See note on 1Ki 3:5.

1:10 wisdom and knowledge. Solomon’s request for wisdom and knowledge connects with the ancient Near Eastern motif of “the king as sage.” Ancient Near Eastern kings were commonly portrayed as wise sages who received their wisdom as an act of favor by their respective deities. Such descriptions frequently include an assessment that the king’s wisdom surpasses that of all others (cf. 2Ch 9:22). Hammurapi, e.g., refers to the “breadth of vision” given to him by the god Ea and declares, “My words are precious, my wisdom is unrivaled.” Likewise, in the eighth-century BC Phoenician Karatepe Stele, Azatiwata (Azitawadda) boasts that “every king made me father to himself because of my wisdom and my goodness.” In the ancient Near East, wisdom was not as much abstract as it was functional. Thus, from the perspective of the king, wisdom had functionality in important areas such as practical knowledge, decision making and temple building. In the realm of knowledge, wisdom was characterized by mastery of areas such as botany, zoology, music, law, diplomacy, flora, fauna, literature and other elements of the cultured life (cf. 1Ki 4:32–33). With respect to decision making, note that Solomon’s request for wisdom is connected to his ability to judge (“govern”) God’s people and facilitate an ordered society. In like manner, ancient Near Eastern kings are commonly portrayed as champions of justice and protectors of the disenfranchised. The Babylonian king Hammurapi (eighteenth century BC), e.g., noted that the gods Anu and Bel called him to cause justice, enlightenment and welfare to prevail in the land. With respect to royal building, particularly of temples, divinely gifted wisdom is stressed in a number of ancient Near Eastern texts. In the temple building account of Gudea (twenty-seventh century BC), the notion of royal wisdom is interwoven through the text (see the article “Dreams and Temple Building in the Ancient Near East”). Likewise, the prologue to the legal code of the Babylonian king Hammurapi (eighteenth century BC) refers to his wisdom in the context of rebuilding the religious shrines of several deities. Similarly, the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar (sixth century BC) is described as a “wise expert who is attentive to the ways of the gods” in conjunction with his refurbishing work on the shrines of Marduk and Nabu. Later, the Babylonian king Nabonidus records in the Sippar Cylinder that during an auspicious day he was instilled with wisdom by the gods Shamash and Adad in conjunction with his work on the temple of the moon god Sin. In the case of Solomon, the stress on his divinely gifted wisdom connects him with Bezalel, who is similarly noted as being given wisdom and knowledge by God for the task of constructing the tabernacle in the wilderness (cf. Ex. 31:1–5; 35:30–35; 36:1). this great people of yours. The notion of the ownership of people, kingdom and throne is sometimes blurred between the ruler and the deity. As such, the king may be portrayed as a divine vice-regent or divine son (perhaps elected or adopted as such; cf. 1Ch 28:6). Thutmose III, e.g., notes the following concerning his god Amon: “He is my father and I am his son,” and Amon commanded that “I should be upon his throne.” Similarly, Thutmose IV is told by his god in a revelatory dream that “thou art my son . . . I am thy father” and “I shall give thee my kingdom.” In the case of the Israelite monarchy, numerous Biblical texts make it clear that the people led by the king are God’s people (here), the kingdom is God’s kingdom (13:8; 1Ch 17:14) and the king sits on God’s throne (2Ch 9:8).

1:17 imported a chariot from Egypt. While the data for prices of chariots are limited, it seems clear that the price point of 600 shekels of silver (about 15 pounds or 6.9 kilograms) for a chariot is quite steep. This price point suggests that these are no ordinary chariots, but rather richly appointed chariots that would be utilized by royalty in processions and state ceremonies. Such chariots, commonly adorned with gold and precious stones such as lapis lazuli (a greatly prized deep blue gemstone), were viewed as surrogate thrones and status symbols for ancient Near Eastern monarchs. Thus, in the Gilgamesh Epic, the goddess Ishtar tries to woo Gilgamesh by offering him an abundant life that includes a chariot adorned with gold and lapis lazuli.

The most famous Egyptian gold chariot is that of King Tut in the Egyptian museum (c. 1330s BC). Another mention of gold chariots from Egypt is found in an Amarna letter sent from Egypt to Babylon in which the Egyptian pharaoh notes that he has sent the Babylonian king two chariots overlaid with gold. Similarly, Papyrus Anastasi IV describes the chariots of the pharaoh as being made of ornate wood and adorned with gold and ivory. The combination of Nubian acacia wood (noted for its quality and hardness) and the use of ivory may have added to the value of Egyptian chariots.

Egypt also acquired gold chariots in battle, as reflected in Thutmose III’s claim that he acquired “magnificent chariots of gold and silver” in plunder from Megiddo (fifteenth century BC). Egyptian pharaohs also received gold chariots as gifts. In a diplomatic letter sent from the king of Assyria to the king of Egypt, the Assyrian king (Ashur-Uballit) notes that he sent the Egyptian pharaoh “a beautiful royal chariot,” along with two white horses. Similarly, Tushratta king of Mitanni sent a chariot covered with 320 shekels of gold as a wedding gift to Pharaoh Nimmureya.

2:1 Solomon gave orders to build a temple. Unlike the account of Solomon’s building activities in 1 Kings (e.g., 1Ki 7:1–12), the Chronicler only mentions Solomon’s palace in passing (2Ch 8:1). Instead, the central narrative focus of chs. 2–9 is the construction of the Jerusalem temple (chs. 2–7). The construction of a new temple or refurbishing of an important religious shrine was an important task for a new king, and preparations for the project would begin soon after the monarch’s enthronement. In order to tangibly illustrate the king’s devotion and to acknowledge the role of the deity in his reign, emphasis was placed on showing that no expense was spared in the procurement of materials for the temple.

Similarly, temple construction accounts stressed the skill and workmanship of the craftsmen employed to build the temple. For example, the Old Babylonian king Shamshi-Adad notes that his temple project for the god Enlil was “methodically made by the skilled work of the building trade.” In addition, in the Sippar Cylinder the Babylonian king Nabonidus notes that he rebuilt the temple for the moon-god Sin from “its foundation to its parapet.” All in all, each royal temple builder wanted to show that the goal of his building campaign was to build, in the words of the Sumerian king Gudea, the “foremost temple of all the lands.”

The construction of Solomon’s temple began in his 4th year as king (c. 967 BC) and was completed in the 11th year of his reign (c. 960 BC). The fact that Solomon did not begin the temple construction until his 4th year reflects the significant amount of preparation and planning that still needed to take place beyond that accomplished by David. See the article “New Kings and Temples.”

2:2 conscripted . . . carriers and . . . stonecutters. See notes on 1Ch 20:3; Jos 16:10; 1Ki 5:13; 9:15.

2:3 Solomon sent this message to Hiram. The exchange of letters between Hiram and Solomon reflects standard practice for official ancient Near Eastern correspondence. Such diplomatic correspondence typically contained expressions of warmth, divine blessings, and even “love” (referring to a relationship loyal to agreed-upon terms). Depending on the history between the two parties, such blessings might include a short review of the relations between the nations and previous rulers. This is seen in an Amarna letter wherein the king of Mitanni notes that the ancestors of the Egyptian pharaoh have “always showed love to my ancestors.” Typically, such letters are geared toward a request from one party to the other, as in the request of the Babylonian king for the Egyptian pharaoh to “send me much gold” for his temple project, noting in return, “whatever you want from my country, write me so that it may be taken to you.” Beyond precious metals and gifts, skilled workmen (e.g., Huram) were another desired “gift.” It is noteworthy that Solomon (like David, cf. 1Ch 22:1–5) readily seeks Phoenician assistance in the building of Yahweh’s temple. The Phoenicians were noted for both supplying crucial building materials as well as the technical expertise to construct buildings and fashion raw materials into artistic objects. See note on 1Ki 5:18. cedar logs. See notes on 2Sa 5:11; 1Ki 5:6; 6:15.

2:5 greater than all other gods. This rhetoric would be expected of any nation. Claims to divine superiority are usually founded in military supremacy or acts of power, and are strongest when coming from the mouths of the former worshipers of the now-deemed-inferior deities (cf. Rahab [Jos 2:11]; Naaman [2Ki 5:15]). See the article “Monotheism, Monolatry and Henotheism.”

2:8 cedar. See notes on 2Sa 5:11; 1Ki 5:6; 6:15. algum. Probably a variant of almugwood.

2:10 I will give your servants. Solomon’s payment of agricultural products and derivatives to Hiram’s workers is formidable and would provide a combination of rations for the Phoenician guest workers and payment for their services. cors. The “cor” is a unit of dry measure equivalent to approximately six bushels (220 liters), making the trade amounts in wheat and barley amount to 120,000 bushels (26.4 million liters) each, i.e., 3,600 tons (3,200 metric tons) of wheat and 3,000 tons (2,700 metric tons) of barley. Twenty thousand cors of grain would have required about 260 acres (slightly more than 100 hectares) of crop from each of Solomon’s 12 districts. wheat . . . barley . . . wine . . . olive oil. These agricultural products were part of Israel’s natural resources (especially the northern tribal regions and portions of the Transjordan). Note that such trade with Tyre/Phoenicia is also implied in the prophecy against Tyre in Ezekiel (Eze 27:17). baths. The “bath” is a unit of liquid measure equivalent to approximately six gallons (22 liters), making Solomon’s shipments of wine and olive oil equal to about 120,000 gallons (440,000 liters) each. Agricultural products from Israel were perhaps transported and stored in cylindrical storage jars (called “sausage jars”) discovered at the Phoenician city of Tyre having features consistent with pottery vessels manufactured in Israel.

The trade interaction noted here between Solomon and Hiram provides an excellent insight into Iron Age trading and barter practices. As reflected here, the natural resources of one region were traded for the natural resources of another at a rate that would be a combination of supply and demand as well as the relative strength and relationship of the trading parties. In this transaction, Solomon’s setting of the price of the trade implies that he is the stronger party in the transaction.

The amounts here describe the “budget” for the project, but each individual worker would have been paid a daily wage. These amounts would have provided rations for 6,000–8,000 workers over three years.

2:14 purple and blue and crimson yarn and fine linen. See note on Ex 25:4.

2:16 float them as rafts by sea down to Joppa. The transporting of wood by means of floating of logs was a practical logistical option for city-states and nations that had access to a seaport. Such transportation of wood over sea is seen in Assyrian reliefs showing logs being towed by Phoenician ships. In addition, the account of Gudea’s temple building project provides a poetic description of the watery journey experienced by the cedar and cypress logs, noting that the logs moved “like majestic snakes floating on water.” Solomon’s ability to transport this wood from the seaport inland to Jerusalem implies his control over the coastal area in the environs of Joppa as well as the Shephelah (low hills) heading eastward to Jerusalem. The journey from Tyre to the port city of Joppa is approximately 100 miles (160 kilometers) and the trip inland to Jerusalem is another 30 miles (50 kilometers) or so.

3:1 Mount Moriah. The location of Mount Moriah is connected with the place where Yahweh appeared to David (1Ch 21) and is described as the place Yahweh chose for the location of the temple (2Ch 7:12). Also, though the historical-geographical connection is tenuous, the name Moriah connects with God’s provision of a substitutionary sacrifice for Abraham, after which the area is called the “mountain of the LORD” (Ge 22:14). This care reflects the importance in the ancient Near East that a religious shrine/temple be located on a divinely chosen or divinely confirmed place. Such concern is also reflected in the Gudea account, wherein Gudea receives signs in dreams designating the divinely chosen location for Ningirsu’s temple. Such a divinely chosen place comes to be understood as holy ground, a notion that contributes to the notion of sacred space (see the article “Temples and Sacred Space”).

3:3 the cubit of the old standard. The system of linear measurement used in ancient Israel was also employed in Egypt and Mesopotamia and was the result of standardizing commonly used measurements based on the length of fingers, hands (four fingers; length of the palm), and forearms (as horses are still measured in “hands” today). (See note on Ex 25:10.) The Chronicler’s statement here reveals the fact that the standard of the cubit would have more than one option in the mind of his audience. While it is difficult to state unequivocally which cubit length the Chronicler had in view, the position here is that the older standard cubit was somewhat longer (about 21 inches) than the more recent standard (about 18 inches).

Using the longer cubit, Solomon’s temple would have been just over 100 feet long and 32 feet wide (just over 30 meters long and 10 meters wide), not counting the portico/porch in the front of the temple (v. 4), which measured 20 by 20 cubits (35 by 35 feet or 10.5 meters by 10.5 meters). Alternatively, if the shorter cubit was in view by the Chronicler, the temple would have measured 90 feet long and 30 feet wide. By way of comparison, an NBA basketball court is 94 feet long and 50 feet wide (28.6 meters long and 15.2 meters wide), making the length of the temple quite comparable and its width narrower by 20 feet.

3:4b overlaid the inside with pure gold. See note on 1Ki 6:22.

3:5 palm tree. A common symbol of fertility, life and agricultural bounty in the ancient Near East, given the ubiquitous date fruit. As such, palm trees are found in palace and temple wall paintings (such as the prominent palms trees in the courtyard at the Mari palace) and on inscribed reliefs, and are referenced in texts. chain designs. Also found on the pillar capitals (1Ki 7:17); it may signify some aspect of God’s character (such as his eternality) or may simply be a common architectural motif. These chains were at the top of the pillars and were adorned with pomegranates (see note on 1Ki 7:15–22).

3:6 gold of Parvaim. The text mentions several grades of gold that increase in purity as one draws closer to the Most Holy Place. Parvaim. Its meaning is uncertain, but most likely refers to a location, perhaps in Arabia.

3:8–9 six hundred talents of fine gold . . . gold nails. Temple building texts customarily list the various precious metals used to construct everything from gold sun disks to bronze fastening pegs. The covering of the interior of a temple in gold is attested in several ancient Near Eastern temple projects. Nebuchadnezzar II, e.g., notes that he used “shiny gold” instead of plaster in his refurbishing work on Marduk’s temple. Similarly, the Assyrian king Esarhaddon notes that he covered walls and doors with gold “as if with plaster” in his restoration of Ashur’s shrine. Also, the last Babylonian king, Nabonidus, covered the walls of the temple of the moon-god Sin with gold and silver, while the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III (fourteenth century BC) plated parts of the temple to Amun at Thebes with gold and silver.

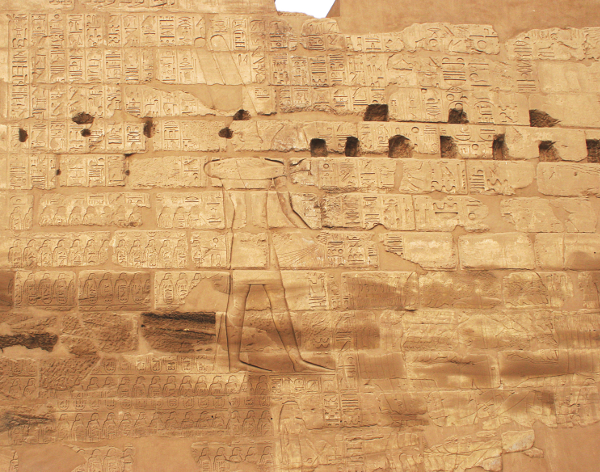

In this text the 600 talents used inside the Most Holy Place would be equivalent to about 23 tons (21 metric tons) of gold, while the weight of the gold “nails” or pegs (50 shekels) amounts to about 1.25 pounds (575 grams) each. While the amount of gold indicated here is significant, it is not without points of comparison to other ancient Near Eastern texts summarizing royal temple donations. The Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III (fifteenth century BC) presented over 200 talents of gold (about 7.5 tons or 6.8 metric tons) to the Amun temple, the details of which (along with other gifts of silver and precious stones) have been inscribed on the walls of the Karnak temple in Thebes (Luxor), Egypt.

Similarly, the twelfth-century BC pharaoh Rameses III lists a wide range of gifts of gold, silver and other precious items to the temples at Thebes (including Medinet Habu, Karnak and Luxor), Heliopolis, Memphis and others. In the Theban section of his Prayer to Amun, Rameses III notes that he “filled its treasury with the products of the lands of Egypt: gold, silver [and] every costly stone by the hundred-thousand.” Later, the tenth-century BC pharaoh Osorkon I enumerates gifts he provided for the various gods and goddesses of Egypt, totaling 375 tons (340 metric tons) of gold and silver (over 10,000 talents of gold and silver). Osorkon’s father was Shishak, who had invaded Israel and had been paid massive amounts of gold and silver that had belonged to Solomon. Therefore, the gift Osorkon made to the gods may well have been inherited from his father, who either received it in tribute or plundered it from Solomon’s successor. Finally, in Mesopotamia, the Assyrian king Sargon II (727–705 BC) claims to have donated 154 talents of gold (5.75 tons or 5.25 metric tons) to his gods. Thus, within this broader historical context, the 600 talents of gold recorded in Solomon’s temple project should not be dismissed by a modern reader as unrealistic.

3:10–13 See note on 1Ki 6:23–28.

3:15 two pillars, which together were thirty-five cubits. The two pillars covered with polished bronze stationed in the front of Solomon’s temple are noted as “together” totaling 35 cubits (about 53 feet or 16 meters) in height (17.5 cubits each, i.e., 26.5 feet or 8 meters). Each impressive pillar had a five-cubit (7.5-foot or 2.25-meter) capital, an ornate top that would have mostly overlapped the top portion of each pillar, creating a stylized arboreal image. The notation in the account in 1Ki 7:15 (cf. 2Ki 25:17; Jer 52:21) specifies a length of 18 cubits per pillar (36 total) versus the 35 cubits noted here (and in the Septuagint, the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT, of Jer 52:21). The difference between the 18-cubit measurement and the 17.5-cubit measurement can be understood as related to the part of the capital extending beyond the top of the pillar (0.5 cubits per pillar). See note on 1Ki 7:15–22.

3:16 interwoven chains. See note on v. 5. pomegranates. See note on 1Ki 7:15–22.

4:2 the Sea of cast metal. See note on 1Ki 7:23–26.

4:5 a handbreadth. The measurement of the width of the palm (four fingers) and thus about three inches (7.5 centimeters). three thousand baths. The capacity (volume) of the bronze Sea is noted at 3,000 baths, which is approximately 18,000 gallons (66,000 liters), an amount comparable to a large above-ground swimming pool.

4:6 basins. The ten basins were mounted on wheels and adorned with various images including cherubim (see 1Ki 7:27–39 and note on 7:27–37). These basins are reminiscent of wheeled basins featuring composite creatures found in Phoenicia as well as on the island of Cyprus dating to the twelfth century BC. Each basin held 40 baths of water (1Ki 7:38), approximately 240 gallons (880 liters). The ten basins were used for ceremonial cleansing of the utensils used within the sacrificial system.

5:12 fine linen. A symbol of wealth, power and religious status (purity) in several ancient Near Eastern cultures. As such, linen gifts in the form of garments, shawls, robes and shoes are found in several gift lists in the Amarna letters, such as the gifts exchanged between the queens of Egypt and Hatti. Similarly, the eleventh-century BC (Egyptian New Kingdom) report of Wenamun’s trip from Egypt to Phoenicia speaks of an array of linen products produced in Egypt that Wenamun was able to trade for timber, suggesting the value of linen at this time. See note on Ex 39:27. cymbals, harps and lyres. See the articles “Lyre,” “Music and Musicians.”

7:1 fire came down from heaven. See note on 1Ki 18:38.

8:2 Solomon rebuilt the villages that Hiram had given him. The relationship between this verse and 1Ki 9:10–14 (where Solomon is described as giving Hiram 20 cities in the region of Galilee) is uncertain. One possibility is that the land was given to Hiram as collateral during the massive flow of Phoenician supplies and workmanship into Israel (1Ki 9:10–14), with the return of this land taking place following the settling of debts (see notes on 2:3, 10).

8:6 store cities, and all the cities for his chariots and for his horses. See note on 1Ki 9:19.

8:11 brought Pharaoh’s daughter . . . to the palace he had built for her. See note on 1Ki 3:1.

8:18 ships . . . sailors. Solomon’s arrangements with Phoenicia extended into maritime trade, with the Phoenicians supplying both ships and experienced sailors. The Phoenicians were noted sailors in the ancient world and built on the accomplishments of earlier merchants such as those of the northern Syrian port city of Ugarit. The Egyptian language even came to include the term “Byblos Ship” to denote high quality vessels from Phoenicia. A painting in the tomb of Qenamon/Kenamon at Thebes (c. 1400 BC) depicts what might be Phoenician ships unloading cargo at an Egyptian port. In addition, an eighth/seventh-century BC Hebrew seal shows a clear image of a sailing ship, perhaps of the Phoenician type utilized by Solomon; this reflects a functioning maritime economy in ancient Israel. Such trading vessels typically ranged from 40 to 80 feet (12 to 24 meters) in length and were powered by sails (single mast) and oars. Commercial shipping was attested in the ancient Near East from at least as early as the third millennium BC, including the shipping routes from along the Mediterranean coast between Egypt and ports in Phoenicia (e.g., Byblos, Tyre, Sidon), Syria (e.g., Ugarit) and beyond, as well as routes from Egypt to Africa (e.g., Punt) and Arabia. The description of these ships as “ships that could go to Tarshish” (see NIV text note on 9:21) together with their three-year trading journey (9:21) implies that these ships could manage the high seas and undertake long-distance sea travel, although most travel was within sight of land (see note on 1Ki 10:22). Note that a three-year sea journey is also the length of time recorded for a trip circumnavigating Africa during the reign of pharaoh Necho II (seventh century BC) as recorded in Herodotus 4.42. In addition to the exchange of normal trade items such as regional agricultural products, metals and timber, such maritime journeys also featured the acquisition of exotic cargo (note the “apes and baboons,” 2Ch 9:21), reflecting the penchant of ancient Near Eastern monarchs for unusual items. Rulers often boasted about their collections of exotic animals (such as two-humped camels, “river oxen,” antelopes, elephants, baboons and peacocks) and even dancing pygmies. These exotic items were depicted in scenes inscribed on the walls of the temples (such as Deir el-Bahri in Egypt) and woven into literature (such as the Story of the Shipwrecked Sailor). Ophir. See note 1Ki 9:28.

9:1 queen of Sheba. See note on 1Ki 10:1.

9:4 food on his table. See note on 1Ki 10:5.

9:9 120 talents of gold. A talent was about 75 pounds, meaning Sheba’s gift was about 4.5 tons (4 metric tons) of gold. It is possible that this large gift was part of a broader commercial trading agreement negotiated between Solomon and the queen of Sheba (see note on 1Ki 10:1).

9:10 gold from Ophir. See note on 1Ki 9:28.

9:13 gold . . . received yearly was 666 talents. See note on 1Ki 10:14.

9:15 shields of hammered gold. See note on 1Ki 10:16.

9:16 Palace of the Forest of Lebanon. This palace is given further description in 1Ki 7 (see notes on 1Ki 7:2, 6) and probably derives its name from its dozens of cedar pillars inside (which would have a tree-like appearance) along with the cedar paneling on the walls and cedar beams on the ceiling. This palace may have functioned as an alternate residence for the king, as well as a more convenient place to meet trading partners and dignitaries from the north.

9:17–19 See note on 1Ki 10:18–20.

9:21 trading ships. See notes on 8:18; 1Ki 10:22.

9:22, 23 wisdom. See note on 1:10.

9:25 four thousand stalls for horses and chariots. See note on 1Ki 4:26.

9:27 silver as common in Jerusalem as stones. See note on 1Ki 10:27. cedar. See notes on 2Sa 5:11; 1Ki 5:6; 6:15.

9:28 horses were imported from Egypt. See note on 1Ki 10:28–29; see also the article “All the King’s Horses.”

10:4 harsh labor. See note on 1Ki 12:4.

10:11 scorpions. See note on 1Ki 12:11.

10:16 What share do we have in David . . . Look after your own house, David! See note on 1Ki 12:16.

11:1 a hundred and eighty thousand. See the article “Numbers in Numbers.”

11:5–12 Rehoboam’s fortified cities address the strategic threats to Judah following the division of the kingdom, including the erstwhile foes to the east (Moab, Ammon, Edom), the perennial enemy to the west (Philistines), and the threat of Egypt to the south. All told, the focal point is the defense of access points to Jerusalem.

11:15 goat . . . idols. Their significance is uncertain, but they may be a representation of satyr-like demons understood to traverse deserted wastelands. Alternatively, gold and silver statues of goats from Ur may imply a possible connection with the tree of life and/or Asherah, as these statues portray the goats standing upright with their forelegs fastened to a tree. calf idols. See note on 1Ki 12:28.

12:2 Shishak king of Egypt attacked. See note on 1Ki 14:25.

12:3 Libyans, Sukkites and Cushites. See note on 1Ki 14:25.

12:13 His mother’s name was Naamah . . . an Ammonite. See note on 1Ki 2:19.

12:15 continual warfare between Rehoboam and Jeroboam. On top of the losses inflicted by Pharaoh Shishak, the northern kingdom and southern kingdom engaged in prolonged strife and conflict. Much of the warfare between Rehoboam and Jeroboam consisted of a back-and-forth battle for Benjamin (particularly the central Benjamin plateau), the strategic tribal area just to the north of Jerusalem.

13:2 war between Abijah and Jeroboam. The conflict that began between Jeroboam and Rehoboam (12:15) continued into the reign of Abijah, successor to Rehoboam in Judah. Even though Jeroboam’s army is described as being double that of Abijah’s, the battle highlighted in ch. 13 implies that Abijah is on the offensive. His rhetoric suggests that it is his intention to reunite the north and south, by conquest if necessary. Abijah’s victory over Jeroboam gives Judah control of the two major north-south highways connecting the southern kingdom and northern kingdom and control over the coveted Benjamin plateau, as well as a portion of the Ephraimite hill country. The remark in v. 20 that “Jeroboam did not regain power” may be related to Aramean pressure on the northern kingdom as facilitated by a treaty Abijah apparently made with Ben-Hadad of Aram (Syria).

13:3 For the size of these armies, see the article “Numbers in Numbers.”

13:5 covenant of salt. See note on Lev 2:13.

13:8 have with you the golden calves. It was common practice to carry images representing the gods into battle. See the article “Divine Warfare.”

14:3 high places. See notes on 1:3; 1Ki 3:2; 11:7. sacred stones . . . Asherah poles. See notes on Dt 7:5; 1Ki 14:23.

14:5 high places. See notes on 1:3; 1Ki 3:2; 11:7.

14:6 fortified cities of Judah. Likely the same cities fortified by Solomon and Rehoboam but destroyed by Shishak (see notes on 11:5–12; 1Ki 14:25).

14:8 three hundred thousand. See the article “Numbers in Numbers.”

14:9 Zerah the Cushite. Although Egypt is not named within the account of vv. 9–15, the close connection between the region of Cush/Nubia and Egypt, as well as the inclusion of Libyans along with Cushites in 16:8, may imply that Zerah was a field general on behalf of an Egyptian pharaoh (presumably Osorkon I). Alternatively, Zerah may have been the chief of an Arab coalition (from the Sinai region), given the pairing of Cushites with Midianites in OT texts and the references to camels and herdsmen in v. 15.

15:16 queen mother. See note on 1Ki 2:19. Asherah. Refers to an Asherah pole (see notes on Dt 7:5; 1Ki 14:23).

16:1 Ramah. See note on 1Ki 15:17.

16:2 Ben-Hadad. See note on 1Ki 15:18.

16:12 disease in his feet. Asa’s affliction has been attributed to gout (uncommon in Biblical times) or gangrene. physicians. Specialists in magical and/or herbal remedies; they operated under the aegis of various gods and in their power.

16:14 made a huge fire in his honor. A funerary pyre was a statement of respect and honor for the deceased and was typically only available for those of high position. Such fires were honorary acts rather than a means of cremation. Attendees would then have made a pile of stones over the place to commemorate the dead king. Similar rites of burning are evident in the Neo-Assyrian substitute king rituals in which the performance of the burning (Akkadian šuruptu) took place after the burial.

17:3 The LORD was with Jehoshaphat. See note on 1:1.

17:6 high places. See notes on 1:3; 1Ki 3:2; 11:7. Asherah poles. See notes on Dt 7:5; 1Ki 14:23.

17:11 gifts and silver as tribute . . . flocks. This tribute, together with statements of military fortifications (vv. 13, 19), makes it clear that the southern kingdom now controls the caravan routes across the Arabah and Negev and on to the Coastal Highway (see note on 2Ki 23:29), providing a lucrative source of tax and tribute income for Jehoshaphat’s administration. This economic and political stability will in turn allow for further military strengthening, building projects and governmental expansion (vv. 12–19). Arabs. Likely seminomadic tribes in the desert regions to the south of the Judahite Negev and portions of the Sinaitic and (perhaps) Arabian peninsulas.

17:14–18 For these large numbers of fighting men, see the article “Numbers in Numbers.”

18:1 Jehoshaphat . . . allied himself with Ahab by marriage. Despite the initial posture of uncertainty (or hostility) toward the northern kingdom (17:1–2), Jehoshaphat ultimately attained peace with Ahab, a diplomatic act culminating in a political marriage between Jehoshaphat’s son Jehoram and Ahab’s daughter Athaliah (21:5–6). See notes on 1Sa 18:25; 25:39b.

18:18 multitudes of heaven. See the article “Divine Council.”

19:3 Asherah poles. See notes on Dt 7:5; 1Ki 14:23.

19:5–11 Jehoshaphat’s appointment of judges in the fortified cities of Judah (v. 5) and his exhortation to these judges (vv. 6–7) suggests a reform of the judiciary. Likewise, his appointment of select Levites, priests and family leaders within Jerusalem to handle appeals (vv. 8–11) suggests a centralization of the judicial system within the southern kingdom. Such reforms were common in conjunction with a new administration, as seen in the similar reforms enacted by the fourteenth-century BC Egyptian pharaoh Horemheb. Legal disputes sometimes involved oracular judgments, or the seeking of divine verdicts by religious professionals (see the article “Divine Verdict”), which is why the Levites and priests are involved.

20:1–30 Sensing weakness following the defeat of Jehoshaphat and Ahab at Ramoth Gilead, an eastern coalition joins forces against Jehoshaphat. This account (not found in 2 Kings) has two areas of uncertainty as to the makeup of this coalition. (1) The Hebrew text has “Ammonites” where the NIV has posited “Meunites” (v. 1). This NIV reading is attested in the Septuagint, the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT, and alleviates what would seem to be an unlikely expression (i.e., “Moabites and Ammonites with some of the Ammonites”). Moreover, since the “men from . . . Mount Seir” function later in the passage (see vv. 10, 22) as synonyms for the third part of the coalition (Meunites), the proposal has merit. The Meunites were an Arabian tribe who lived in the southern region of the Transjordan and parts of the Sinai; they paid tribute to Judah during the reign of Uzziah (26:7–8) and are mentioned in Assyrian annals as paying tribute to Tiglath-Pileser III (eighth century BC). (2) The Hebrew text notes that the coalition is attacking “from Aram” (v. 2), which the NIV has rendered “from Edom.” If Aram is the intended nation, the passage would indicate that these eastern nations were being supported (if not incited) by Damascus, perhaps as a means of reprisal against Jehoshaphat in his help of Ahab’s assault on Ramoth Gilead.

20:28 harps and lyres and trumpets. See the articles “Lyre,” “Music and Musicians.”

20:34 annals. See note on 1Ki 14:19.

20:36 trading ships. See notes on 8:18; 1Ki 10:22.

21:4 Jehoram . . . put all his brothers to the sword. See note on 2Ki 10:7.

21:7 lamp. See note on 2Ki 8:19.

21:10 Libnah. See note on 2Ki 8:22.

21:16–17 the Philistines and . . . the Arabs . . . attacked Judah. In addition to the rebellion of Edom and Libnah (vv. 8–10), Jehoram also faced attacks on Judah (including Jerusalem) from regional foes to the south and west. These Arabs were located in the desert regions to the south of the Judahite Negev into portions of the Sinai peninsula. The Cushites noted here as adjacent to the Arabs might relate to the battle of Zerah, which would place them in the vicinity of Gerar, in the southern region of the Negev (14:9–13). The Arab raiders are credited with killing all of Jehoram’s sons except Ahaziah (22:1). In addition to the difficulties of fighting battles on multiple fronts, the loss of Judah’s hegemony over these areas entailed the loss of tribute payments and caravan (trade) revenue.

21:20 not in the tombs of the kings. As with the withholding of a fire in the honor of Jehoram following his death (v. 19; see note on 16:14), Jehoram was also denied the honor of being buried in the royal cemetery. See note on 1Ki 2:10.

22:1 The people of Jerusalem. See note on 23:20. the Arabs. See note on 21:16–17.

23:1–11 This episode in the history of Judah illustrates the power behind the priesthood. The power of the priest extending into the political realm is similar to the degree of power and privilege afforded priests in other ancient Near Eastern societies. Priests have land holdings and assets, and the emotional support of the people. Jehoiada is also Joram’s son-in-law and so is connected by marriage to the royal line.

23:19 gatekeepers. See note on 1Ch 9:17.

23:20 people of the land. The sociopolitical group designated the “people of the land” factors into several significant regnal change narratives, including those of Joash (here; vv. 13, 21), Josiah (33:25), and Jehoahaz (36:1). This group is also referenced several times in Jeremiah (Jer 1:18; 34:19; 44:21) in a way that implies these individuals were regular citizens, perhaps clan leadership rather than royal officials. Nevertheless, the ability of this group to impact regnal changes shows that the “people of the land” functioned as power brokers regardless of their official status within the kingdom.

While it is difficult to completely deduce the political and/or religious objectives of the “people of the land,” the pivotal nature of the contexts in which they appear and influence the political (regnal) process is noteworthy. The “people of the land” facilitate the coronation of Jehoahaz (36:1) following the death of Josiah at Megiddo (35:20–24). In putting Jehoahaz onto the throne, the “people of the land” pass over the oldest son of Josiah (Eliakim), implying that they see Jehoahaz as a better fit for their agenda, which may have been pro-Babylonian and anti-Egyptian (as Josiah’s actions at Megiddo reflect).

This possibility is bolstered by the fact that Pharaoh Necho II deposes Jehoahaz after three months and replaces him with Eliakim (Jehoiakim). Similarly, note the role of the “people of the land” in the political dynamics surrounding the assassination of Amon (33:24–25). All told, the usage of this expression at pivotal moments in Judah’s history provides some insight into the social dynamics of ancient Judah, including contrasting views of foreign policy and perhaps even tensions between urban and rural citizenry.

24:1 Joash. Began his reign as a seven-year-old child, no doubt under the close guidance of Jehoiada the priest. Joash’s long reign (c. 835–796 BC) overlaps with those of Jehu and Jehoahaz in the northern kingdom and reflects a time of Aramean resurgence under Hazael and Ben-Hadad and continued strength in Assyria, particular under the rule of Shalmaneser III and Adadnirari III.

24:4–14 As with the construction of a new temple, the refurbishing of an existing religious shrine was an important task for a new ruler, as reflected in Joash’s efforts as well as those of Hezekiah (29:3–36) and Josiah (34:8–13). See notes on 2:1; 2Ki 12:5.

24:15 old and full of years. Death at an old age was considered to be a divine blessing on a life well lived. Death at an old age is the summary remark in the tomb inscription of the Egyptian leader Ahmose, who is credited with expelling the Hyksos from Egypt. Likewise, in the OT, the attaining of old age is seen as a blessing of God (e.g., Ps 91:16) as well as a by-product of wisdom (Pr 3:16). Idealized numbers for time of death include 110 in Egyptian thought and 120 in Mesopotamian thought.

24:18 Asherah poles. See notes on Dt 7:5; 1Ki 14:23.

24:23–27 See note on 2Ki 12:17.

25:5 three hundred thousand men. See the article “Numbers in Numbers.”

25:12 threw them down . . . dashed to pieces. Throwing enemy prisoners off a cliff is not known outside this passage. It was likely employed for convenience given the geographic location.

25:13 raided towns belonging to Judah. Following a prophetic challenge, Amaziah decides against using the mercenary troops from Israel, which prompts them to plunder Judahite cities from “Samaria to Beth Horon.” Given that the northern kingdom capital Samaria was not a Judahite town and that it was over 50 miles (80 kilometers) away, Samaria here may be the name of a Judahite town or may reflect a textual transmission issue. The statement may also simply reflect the direction of the attack on Judahite towns.

25:14 gods of the people of Seir. The national god of Seir (i.e., Edom) is Qos. Though sometimes the gods of the enemy were smashed or subjugated, it is not unusual to offer worship to the gods of defeated enemies if there is some sense that those gods fought on your side. Their favor could be considered as important as that of native gods.

25:24 hostages. The taking of hostages was a common way to ensure continued power over a conquered area, as reflected in the tactics of the Assyrian king Sennacherib, who took the relatives of Marduk-Baladan and those who were assisting him to discourage his ongoing acts of rebellion.

25:27 Lachish. See note on 2Ki 14:19.

26:1 the people of Judah. See note on 23:20.

26:2 rebuilt Elath and restored it to Judah. See note on 2Ki 14:22.

26:13 307,500 men. See the article “Numbers in Numbers.”

26:14 shields, spears, helmets, coats of armor, bows and slingstones. Assyrian reliefs indicate a wide variety of shields, spears, bows and battle armament, including coats of armor used for chariot warfare. Uzziah’s impressive efforts for his army are an indirect statement on the economic and political stability of Judah at this time.

26:15 devices invented for use on the towers and on the corner defenses so that soldiers could shoot arrows and hurl large stones from the walls. The specifics of these military machines are not clear. Their design and the remark that Uzziah’s fame spread far and wide as a result of this equipment implies that these were impressive devices (at least within a Judahite context). While catapult-like devices are not known in the ancient world until several hundred years later, the view that these “devices” were essentially shields to protect soldiers as they shot arrows or threw stones ignores the engineering and design emphasis of the passage. In any case, these devices created a military advantage for a city under siege.

26:19 leprosy. See notes on Ex 4:6; Lev 13:2. Yahdun-Lim of Mari calls down a curse of leprosy on whoever desecrates the temple he is dedicating, so the association of the disease with cultic impropriety seems to be a known theme.

27:5 Jotham waged war against the king of the Ammonites. Jotham continued the domination of Ammon attained by his father, Uzziah. Since the northern kingdom retained the Transjordan tribes (Gad, Reuben and part of Manasseh) and exercised hegemony over Transjordan nations such as Moab, Uzziah and Jotham’s expansion of southern kingdom–interests to Ammon are impressive and likely relate to the warmed relations between Israel and Judah during this time. the Ammonites paid him. The amount of silver tribute received by Jotham noted here is staggering. A talent weighed about 75 pounds, so that Ammon’s tribute was about 3.75 tons (3.4 metric tons) of silver.

28:3 sacrificed his children in the fire. See notes on Lev 20:2; 1Ki 11:5; 2Ki 3:27; 16:3; Jer 7:31.

28:6 a hundred and twenty thousand soldiers. See the article “Numbers in Numbers.”

28:16–21 See the article “Israel and Damascus Versus Judah.”

28:24 set up altars at every street corner. Babylonian texts refer to small, open-air shrines located on street corners. The city of Babylon was said to contain 180 of them dedicated to Ishtar.

28:27 not placed in the tombs of the kings of Israel. See note on 21:20.

31:1 sacred stones . . . Asherah poles. See notes on Dt 7:5; 1Ki 14:23. high places. See notes on 1:3; 1Ki 3:2; 11:7.

31:11 storerooms in the temple. See the article “Architecture of the Temple.” Hezekiah’s efforts are either a revamping of existing storage in Solomon’s temple or an expansion of storage capacity in light of the renewed focus on temple worship.

32:1 Sennacherib king of Assyria . . . invaded Judah. See note on 2Ki 18:13; see also the article “Hezekiah and Assyria.”

32:9 Lachish. See notes on 2Ki 14:19; 18:14. officers. See note on 2Ki 18:17.

32:21 some of his sons . . . cut him down with the sword. See the article “The Death of Sennacherib.” In order to close out the account, the death notice of Sennacherib is given, although his actual death does not come for another 20 years.

32:31 envoys were sent by the rulers of Babylon. See note on 2Ki 20:12.

33:3 high places. See notes on 1:3; 1Ki 3:2; 11:7. Asherah poles. See notes on Dt 7:5; 1Ki 14:23. starry hosts. See note on 2Ki 21:3.

33:6 sacrificed his children in the fire. See notes on Lev 20:2; 1Ki 11:5; 2Ki 3:27; 16:3; Jer 7:31.

33:11 the king of Assyria . . . took Manasseh prisoner. See the article “Manasseh of Judah and Ashurbanipal.”

33:19 high places. See notes on 1:3; 1Ki 3:2; 11:7. Asherah poles. See notes on Dt 7:5; 1Ki 14:23.

33:25 people of the land. See note on 23:20.

34:8 repair the temple of the LORD. See note on 24:4–14.

34:14 found the Book of the Law. See note on 2Ki 22:8.

34:22 the prophet Huldah . . . wife of Shallum . . . keeper of the wardrobe. See note on 2Ki 22:14.

35:20 Necho king of Egypt. See note on 2Ki 23:29.

36:1 people of the land. See note on 23:20.

36:4 changed Eliakim’s name to Jehoiakim. See note on Ge 2:20.

36:6 Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon attacked. See note on 2Ki 24:10.

36:10 brought him to Babylon. See note on 2Ki 24:14.

36:13 also rebelled against King Nebuchadnezzar. See note on 2Ki 24:20.

36:21 seventy years. The beginning point and ending point of Jeremiah’s prophecy of 70 years of exile (Jer 25:8–14) is not exactly specified within the Biblical material. One option is to see the destruction of the temple in 586/585 BC as inaugurating this period, which then comes to a close with the dedication of the rebuilt temple in 516/515 BC. Another option is understanding the decree of Cyrus (539 BC; see v. 22; Ezr 1:1–4) as signaling the end of the 70 years, which implies a beginning point at the death of Josiah, at which point the southern kingdom lost its independence and became a pawn to the geopolitical interests of Egypt and Babylonia.

36:22–23 The death of Nebuchadnezzar II in 562 BC set in motion the beginning of the end of the Babylonian Empire. His son Awel-Marduk was assassinated after two years and the next two Babylonian kings (Neriglissar [probably “Nergal-Sharezer, Jer 39:3] and Labashi-Marduk) reigned for a combined five years or so before Nabonidus assumed the throne. Nabonidus ruled Babylon 556–539 BC, but his interest in the moon-god Sin (rather than Marduk) caused numerous issues, and within a few years Nabonidus departed for the Arabian oasis city of Tema (some 500 miles [800 kilometers] from Babylon) and appointed his son Belshazzar to rule in his stead.

Meanwhile, Persia continued to gain strength and encroach on Babylonian territory, so that by 546 BC Persia was controlling much of the southern region of Babylonia and closing in on Babylon. In 539 BC, Cyrus the Persian (559–530 BC) took Babylon with hardly a fight and presented himself as a loyal worshiper of Marduk and the liberator of the Babylonian people. The Persian Empire ruled the ancient Near East 539–333 BC.

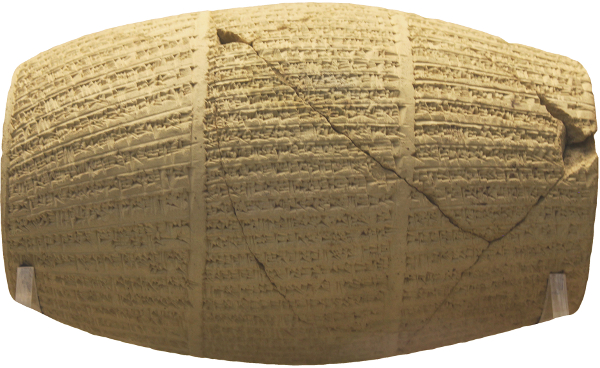

By conquering the Babylonian Empire, Cyrus inherited various nations exiled to Babylon and overturned the foreign policy of the Babylonians by allowing peoples previously deported to return to their homeland if they so desired. Thus, within the first year of his rule Cyrus issued proclamations to this effect, as reflected in the Cyrus Cylinder (Clay Barrel; see illustration in “Ancient Texts Relating to the Old Testament”). Cyrus also sought to placate the gods of these people groups by encouraging traditional worship of local deities, as reflected in his respect of Marduk and his reverential words toward Yahweh (v. 23). One way to do this was by returning religious articles seized by the Babylonians and by funding rebuilding efforts of temples and shrines (Ezr 1:2–8; 6:1–12).