Annotations for 1 Samuel

1:2 He had two wives. On polygyny (having more than one wife), see note on Ge 16:2. Most cases of polygyny among commoners occurred prior to the time of the monarchy. The practice was not especially common among the Israelites and generally occurred when the first wife married was barren, when marriage was required to provide offspring for a deceased brother, or for the political reasons of building alliances. Peninnah had children, but Hannah had none. Hannah found herself not only in the difficult position of having a rival wife, but in the pitiable position of having no children (see note on Ge 11:30). Given the order in which she and Peninnah are named, Hannah was probably Elkanah’s first wife, and it may have been her barrenness that prompted Elkanah to take a second wife. In the broader ancient Near East, fertility was a major concern for women and even for men, the more so as fertility was regarded as under the control of God (v. 5) or the gods, and lack of fertility could be understood as a curse.

1:3 Year after year this man went up from his town to worship and sacrifice. Religious life in the ancient Near East, as in the Bible, was marked by feasts and festivals. The Pentateuch makes reference to three annual pilgrim festivals: the Festival of Unleavened Bread, the Festival of Weeks and the Festival of Tabernacles (Dt 16:16; cf. Ex 23:14–17; 34:18–23; Dt 16:1–15). An “annual festival of the LORD in Shiloh” is mentioned in Jdg 21:19, and it may have been this festival to which Elkanah and his family went, or they may have gone to Shiloh simply in observance of a family ceremony (the existence of family ceremonies is suggested by David’s excuse in 1Sa 20:6). LORD Almighty. This divine appellation, referring to Yahweh as the commander of armies (heavenly hosts) occurs here for the first time in the OT. Shiloh. Biblical Shiloh is identified with modern Khirbet Seilun, which lies midway between Shechem to the north and Bethel and Jerusalem to the south. First mentioned in Jos 18:1, Shiloh was the place where Joshua designated the tribal allotments after the initial conquest (Jos 19:51). Shiloh became the site of an annual festival during the period of the judges (Jdg 21:19), and at least by the end of the judges period Shiloh had become the home of the priestly family of Eli and of the ark of the covenant (1Sa 4:3; 14:3). Ps 78:60 and especially Jer 7:12 suggest that Shiloh may have served as Israel’s first “central sanctuary,” and Jer 7:14; 26:6, 9 imply that the city was destroyed or at least abandoned after Israel’s defeat by the Philistines in 1Sa 4. Hophni and Phinehas, the two sons of Eli, were priests of the LORD. That Eli is simply mentioned without further introduction suggests that he must have been well-known to the original audience(s) of this story. He appears to have been both judge (cf. 4:18) and high priest as the period of the judges was drawing to a close—though he is never explicitly called high priest. Combining the evidence of several Biblical passages (e.g., 14:3; 22:9, 11, 20; 1Ch 24:3), we may conclude that Eli descended from Aaron’s fourth son, Ithamar, rather than from his third son, Eleazar, whose line had occupied the high priestly office at the beginning of the period of the judges (see, e.g., Jos 22:31–32; Jdg 20:28). How the transfer of responsibility from the house of Eleazar to the house of Ithamar took place remains obscure, as the question is not addressed in Scripture.

1:4 give portions of the meat. While some sacrifices were completely consumed by fire (e.g., whole burnt offerings; see Lev 1 and notes), others such as the fellowship offerings (see Lev 3 and notes; 7:11–34) stipulated portions to be eaten by those participating in the sacrifice (see note on Lev 3:1).

1:5 to Hannah he gave a double portion. Dt 21:17 speaks of a “double share” being given to the firstborn son, even if he is the son of an unloved wife. Many commentators assume a similar meaning here, i.e., a “double portion” given to the beloved but barren wife. The Hebrew expression in the present context is, however, different from the expression in Dt 21:17, and its sense is much debated. Whatever the nature of this portion, it could not compensate for other factors such as the social stigma associated with barrenness, the need for offspring to assure the social security of aging parents, etc.

1:9 the LORD’s house. Mention of “the LORD’s house” at this stage in Israel’s history may seem anachronistic, inasmuch as Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem would not be built until more than 70 years later, and, in any case, 2Sa 7:6 indicates clearly that the Lord’s house prior to King David’s time was a tent. This is confirmed by Ps 78:60, which speaks unmistakably of the Lord’s “tent” at Shiloh. The best approach is to understand the “house” here and also in 3:3 as referring to the tabernacle. Given the fact that the tabernacle is designated in several different ways in Samuel—e.g., “the house of the LORD” (v. 7; 3:15) and “the tent of meeting” (2:22)—and the fact that other portions of Scripture exhibit a similar variety of expression (e.g., Ps 27:4–5), one should not make too much of the fact that the tabernacle is called the Lord’s “house.” That said, the mention of the “doorpost” here and the “doors” in 3:15 does seem to suggest a more permanent structure than has typically been associated with the tabernacle, and, indeed, there may have a been a more substantial “house” at Shiloh that held the tabernacle inside it, though no archaeological evidence of such a structure has been uncovered at Shiloh.

1:11 made a vow. The making of vows was a common practice in the OT world and in the ancient Near East generally, including among Mesopotamians, Hittites, Phoenicians, Egyptians and the people of Ugarit. Often the vow was made to God (or a god) and involved an agreement by the one making the vow to do a particular thing (offer a sacrifice, erect a stele, etc.), on the condition that the deity would fulfill a request. (see note on Jdg 11:30). no razor will ever be used on his head. Recalls the second prohibition of the so-called Nazirite vow (Nu 6:1–21). While a Nazirite vow was commonly made for a limited period of time (the end of which would be marked by the shaving of the head and the return of the individual to “normal” status), Hannah consecrated her son for “all the days of his life.” In this respect, Hannah’s vow is reminiscent of the Nazirite charge included in the annunciation of Samson’s birth (Jdg 13:3–7). No similar vows are known from the rest of the ancient world.

1:13 Hannah was praying in her heart. While spontaneous prayer is quite common in the Bible, silent prayer is mentioned explicitly only here. An interesting parallel is found in the Egyptian “Instruction of Any,” which encourages the worshiper to pray words hidden in their hearts.

1:22 After the boy is weaned. In antiquity, a child might be nursed for three years or more. Because the return of ovulation after giving birth can be delayed by breast-feeding, an extended period of nursing may have served as a kind of natural contraceptive.

2:1 horn. Refers, of course, at a literal level to the antlers or horns that served as weapons for various animals; the OT uses “horn” to describe the natural headgear of rams and wild oxen, and even for the tusks of elephants. It is not surprising, therefore, that horns regularly appear in depictions of Mesopotamian deities and kings. As a general metaphor, one’s horn represents one’s strength, pride and security. See the article “Moses’ Horns.”

2:2 there is no Rock like our God. The term “rock” (or “mountain”) occurs in theophoric personal names (names that make a statement of some sort about God) in both the ancient Near East and the OT. As a title (and not a mere metaphor) for the God of the Bible, the term is concentrated in poetic passages such as the song of Moses in Dt 32, the song of David in 2Sa 22, the Psalms and Isaiah. Modern readers, familiar with the use of explosives and heavy machinery to move or even pulverize rocks, must use their imaginations to grasp the sense of “impervious solidity” that a large rock would have evoked in the minds of ancient people. In the Bible, “Rock” is suggestive of God’s strength and sovereignty and of the security, stability and salvation of those who trust in him.

2:6 The LORD brings death and makes alive; he brings down to the grave and raises up. Cf. vv. 3–8. The conviction that the fate of human beings is in the hands of God (or the gods) runs deep in ancient Near Eastern cultures. In the Akkadian creation epic known as the Enuma Elish, we read the following lines: “Thou, Marduk, art the most honored of the great gods, Thy decree is unrivaled, thy word is Anu [i.e., it has the authority of the sky-god Anu]. From this day unchangeable shall be thy pronouncement. To raise or bring low—these shall be (in) thy hand.” And from the Egyptian “Instruction of Amenemope” the following: “He [the deity] tears down and builds up every day, he makes a thousand poor as he wishes, and makes a thousand people overseers, when he is in his hour of life.” See also note on Dt 32:6.

2:10 thunder from heaven. Few displays of nature evoked such a sense of power and danger among ancient people as a severe thunderstorm. Not surprisingly, the ancients often perceived booming thunder as evidence of the powerful presence and judgment of the deity. In the Akkadian flood stories, it is the weather-god Adad that rumbles and thunders in the clouds. In Hittite mythology, Telipinu, also a weather-god, comes raging with lightning and thunder. In Ugaritic texts, the Canaanite god Baal makes “his voice ring out in the clouds, by flashing his lightning to the earth”; he opens “a rift” in the clouds and makes “his holy voice” resound. Since the Israelites lived in the same culture as these other nations, they were used to using similar conventions and imagery to describe their God, even though he had revealed himself as unique from the gods of the nations. He will give strength to his king. That Hannah should refer to the Lord’s “king” may seem surprising, inasmuch as kingship had in her day not yet been introduced in Israel. Kingship was certainly well known among Israel’s neighbors, and it was widely practiced in Egypt and Mesopotamia from at least the third millennium BC. Israel itself had flirted with the idea of kingship already in the days of Abimelek (Jdg 9). Jotham’s fabled response to Abimelek’s bid for power explicitly mentions anointing a king (Jdg 9:8). Prior to the book of Judges, numerous references in the Pentateuch make clear that God intended for Israel one day to have a king (e.g., Ge 17:6; 49:10; Nu 24:7, 17–19; Dt 17:14–20; 28:36). We also find that the word translated “king” here can designate the governor or chieftain of a settlement or city-state (note “the king of Jericho” in Jos 2:2). his anointed. Anointing with oil was widely practiced in ancient Israel and in the ancient Near East. Egyptian officials were anointed to high office, though it is unclear whether the Egyptian king himself, the pharaoh, was also anointed. From the Amarna letters, it appears that local kings in Palestine were anointed as an expression of vassalage to their Egyptian suzerain. Among the Hittites also, it was common for the suzerain to bind his vassals to him by formal rites undergirded by religious sanctions. Among these rites was the anointing of the vassal ruler. Hittite kings themselves were also anointed with the “holy oil of kingship,” and their titles sometimes referred to their anointed status, e.g., “Tabarna, the Anointed, the Great King.” Similar practices are represented in the OT. While both religious objects and religious personnel were anointed (Ex 30:22–33), it was the king who ultimately held the title “the LORD’s anointed” (e.g., 1Sa 16:6) or, in shortened form, “his anointed” (e.g., 12:5) This title expressed the king’s vassal status as the Lord’s earthly representative and his consecration to and authorization for divine service (on vassal kingship, see notes on 8:7; 10:1; 12:3; 24:6). The king’s status as the “anointed” implied his divine enabling and his inviolability.

2:13 three-pronged fork. This and other implements such as tongs were used in religious practice for various purposes—e.g., adjusting sacrificial animals on the altar. Here Eli’s wicked sons are simply plunging the fork into the pot of sacrificial meat, contrary to procedures prescribed in the Pentateuch, which stated that only certain portions of the sacrificial animal were to be eaten by the priests (Lev 10:14–15).

2:15 even before the fat was burned. See note on Lev 3:4. The priest’s duty was to burn the fat on the altar as a pleasing aroma to the Lord (Lev 3:16; 7:31). Both fat and blood were barred from human consumption (Lev 3:17; cf. Lev 7:33; Eze 39:19; 44:7, 15), and anyone who offended in this matter was to be “cut off from their people” (Lev 7:25). Against this background, the abuses of the sons of Eli, described in 1Sa 2:12 as “scoundrels,” were very grave indeed (v. 17). Ritual rules about sacrificial portions and priestly prebends varied from culture to culture and from ritual to ritual. Violation of such rules by the priests who were supposed to safeguard proper practice was always dangerous.

2:18 ephod. The term seems to refer to three distinct but related items in the Bible: (1) the simple linen garment worn by priests (as in the present context); (2) the very elaborate high priestly ephod described especially in Ex 28; 39, upon which was attached a breastplate containing the Urim and Thummim (oracular devices of some sort; see 1Sa 14:3, 18–19); and (3) some other object, perhaps an idol or, more likely, a sacred garment that clothed an idol. (see note on Lev 3:11). What all three types of ephod have in common is their character as a sacred vestment of some sort. Outside the Bible, Old Assyrian texts from Cappadocia attest the possibly cognate term epattu, which designates a “rich and costly garment.” The notice that the boy Samuel was wearing a linen ephod indicates that he had entered the priestly service as an apprentice.

2:19 robe. Probably an outer garment of some sort to be worn over the linen priestly ephod (see note on v. 18). In both the Bible and the ancient Near East generally, robes or special garments often carried symbolic significance or marked the wearer as holding a particular office or status (see note on 18:3–4).

2:22 women who served at the entrance to the tent of meeting. The “tent of meeting,” first mentioned in Ex 27:21, is used frequently in the OT to refer to the pre-Solomonic portable sanctuary where the Lord would appear to his people and their leaders, initially and especially to Moses. In its use here, the designation may be virtually synonymous with the tabernacle. Commentators sometimes have assumed that the women referred to here were engaged in religious prostitution and have likened their activities to those of fertility cults believed to have existed in Canaan. Recent studies have questioned the linkage between prostitution and fertility, however, and have expressed doubt that such prostitution was at all prevalent in the ancient Near East (see note on Ge 38:15). Finally, unlike many of its neighbors, ancient Israel seems not to have included women in the priesthood. On the linguistic level, this is indicated by the absence of a word for “priestess,” in contradistinction to references to priestesses among the Assyrians, Phoenicians and others.

2:27 man of God. Often used in the OT as a synonym for “prophet” (cf. 9:8–11). The phenomenon of prophecy is widely attested in the ancient Near East, from Mesopotamia (Uruk, Mari, Assyria, etc.) to Anatolia (where the Hittites also referred to prophets as “men of God”) to Syria and Palestine (Ebla, Emar, Ugarit, Phoenicia, Aram, Ammon) to Egypt. Although definitions of “prophecy” range from “foretelling the future” to “decrying injustice,” the key element in Biblical (and some ancient Near Eastern) prophecy is that it constitutes inspired speech at the initiative of a divine power. The key distinction between Biblical and other ancient Near Eastern prophecy is the identity of the divine power at whose behest the prophet speaks.

2:28 ephod. See note on v. 18. The present context, which speaks of Eli’s ancestral family approaching the altar and burning incense, suggests that the high priestly ephod is in view.

3:1 not many visions. Judging from the extant evidence, ancient Near Eastern cultures were deeply theological in outlook. It is not surprising, therefore, that “visionaries,” or prophets, who (ostensibly) brought messages from the gods to the people, were a regular feature in most ancient societies. Should any god refuse to communicate through the prophets, it would be a sign of divine displeasure.

3:3 lying down in the house of the LORD, where the ark of God was. This statement has led some to speculate that Samuel may have been engaging in a well-attested ancient Near Eastern practice called “incubation,” which involves spending a night in the temple precinct in the hope of receiving a divine vision or oracular dream. The practice is attested among the Egyptians, with manuals of dream interpretation being used as early as the New Kingdom period, among the Hittites of Anatolia and in Canaan during the Biblical period. However, there is no hint in the text that Samuel intended to incubate a revelatory dream—quite the contrary, as he repeatedly assumed that the voice he heard was Eli’s. Rather, Samuel’s experience would best be called an (unanticipated) auditory dream theophany. No accidental incubation dreams are known from the ancient Near East. The closest to it is found in an Egyptian story in which the prince who was to become Thutmose IV receives a dream while sleeping between the paws of the sphinx (not a temple, but arguably sacred space). Extra-Biblical examples of auditory dream theophanies, or auditory message dreams as they are sometimes called, come from Egypt, Ugarit, Hatti and Babylonia. house of the LORD. See note on 1:9. ark of God. See note on Ex 25:16.

4:1 Philistines. See notes on Ge 21:32; Jdg 3:3.

4:4 cherubim. See note on Ex 25:18.

4:6 Hebrew. The first occurrence of this designation in the books of Samuel. It is perhaps not surprising that this label is found on the lips of a non-Israelite people. Throughout the books of Samuel, as well as elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible, the designation “Hebrew(s)” is often used by foreigners or in the presence of foreigners. A possible explanation for this phenomenon has to do with the much debated link between the “Hebrews” and the so-called Habiru/Apiru known from many documents throughout the ancient Near East, particularly in the second millennium BC (see note on Ge 14:13).

4:10 thirty thousand foot soldiers. See the article “Numbers in Numbers.” See also note on Jos 4:13.

4:12 his clothes torn and dust on his head. The Benjamite messenger’s appearance leaves no doubt that he brings bad news. Grief and distress are often indicated in the Bible (both OT and NT) by actions such as fasting, wailing, breast-beating, tearing of one’s garments, putting on sackcloth or throwing dust (dirt or ashes) on one’s head.

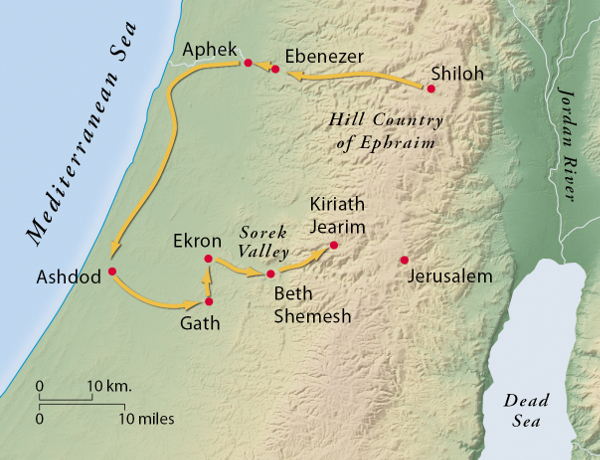

5:1 Ashdod. In the OT period it was one of the cities of the Philistine pentapolis (see note on Jdg 3:3). The city, along with “its surrounding settlements and villages” (Jos 15:47), was assigned to the tribe of Judah, but from the arrival of the Sea Peoples in the late thirteenth and early twelfth century BC until the time of King David (tenth century BC), the city seems to have been in Philistine hands. The city appears to have been a major seaport.

5:2 they carried the ark into Dagon’s temple and set it beside Dagon. Ancient Near Eastern peoples were convinced that their fates were ultimately in the hands of the gods. In keeping with this (poly)theistic mindset, battles were viewed as contests not just between the human opponents but, more importantly, between the deities of the respective sides. A defeat, therefore, was a humiliation not only for the human participants but also for the gods of the losing side. As part of the victor’s despoiling the vanquished, the gods of the losing side were typically carried off and deposited in the temple of the winning god(s) as adjunct deities and/or as a sign of the inferiority and subordination of the captured gods. References to this practice are ubiquitous in ancient Near Eastern battle reports. Although not an idol, the ark of God was treated as such by the Philistines.

5:3–4 there was Dagon . . . His head and hands had been broken off. Decapitation of defeated foes was common practice in the ancient Near East and, indeed, in the books of Samuel (17:51; 31:9; 2Sa 4:7; 16:9). The Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser I (1114–1076 BC), e.g., boasts of his defeat of 20,000 men-at-arms and five kings of the land of Kadmuhu: “Like a storm demon I piled up the corpses of their warriors on the battlefield (and) made their blood flow into the hollows and plains of the mountains. I cut off their heads (and) stacked them like grain piles around their cities.” Severing hands (and sometimes other body parts, see note on 1Sa 18:25) was a convenient way of tabulating and demonstrating enemy casualties. Dagon’s loss of head and hands, therefore, was a sign of unmistakable defeat by the supposedly captive Israelite God, Yahweh, as symbolized by the ark. A variety of occurrences that happened to statues, whether of gods or kings, were often interpreted as omens in the ancient Near East.

5:5 step on the threshold. Peoples of the ancient Near East had a sense of sacred precincts and even of especially sacred spaces within the sacred precincts. In Israel, e.g., one may think of the Most Holy Place within the temple. In the book of Ezekiel, thresholds appear to be of some special significance (Eze 9:3; 10:4, 18; 46:2; 47:1). The avoidance of stepping on the threshold of a sacred precinct was known, if not approved, in Israel (Zep 1:9). Philistine avoidance of thresholds may have begun with the humiliation of Dagon described in the present episode, or it may have been a preexisting practice that the Biblical narrator, for purposes of irony and ridicule, links to the fall and destruction of Dagon at the threshold.

5:6 afflicted them with tumors. Debate over the nature of the Philistine affliction has revolved around two main possibilities: bubonic plague (characterized by tumors, or swellings of the lymph nodes) and bacillary dysentery. Both afflictions could be caused by pathogen-bearing rodents, a particular bane for coastal cities such as Ashdod, where infected rodents could arrive by ship. See the NIV text note on this verse for the long reading of this verse in the Septuagint (the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT), which mentions rats appearing in the land and bringing death and destruction. That the Philistines suspected their woes to be the result of infestation may be inferred also from the Hebrew text of the next chapter, which mentions rodents several times (6:4, 11, 18).

5:8 Gath. Some 12 miles (19 kilometers) east-southeast of Ashdod, the city to which the Philistines first brought the ark in the aftermath of the battle of Ebenezer (4:1–5:1).

6:2 Tell us how we should sent it back to its place. In the ancient world, an outbreak of plague was often considered the work of an angry deity, perhaps the god of an enemy people. In one Hittite text, an enemy god is assumed to be responsible for an outbreak of plague, and in response a chosen animal is decorated and driven back into enemy territory in the hope of pacifying the angry god and ending the plague. This procedure loosely parallels the Philistines’ actions in ch. 6. A second Hittite ritual text offers further parallels, except that it involves human beings (enemy captives) as scapegoats. The last lines describe a kind of apotropaic (turning away) ritual that vaguely resembles the scapegoat ritual in Lev 16:7–10, 21–22 and is even closer (though certainly not identical) to the procedure enacted by the Philistines here in 1Sa 6—both the Philistines and the Hittites express some uncertainty regarding whether their plague was caused by an offended deity (cf. v. 9); both return something or someone representative of the plague or its agents back to enemy territory accompanied by “all the lords” (cf. “the rulers of the Philistines” in v. 12); and both are concerned that the apotropaic objects or persons be of value sufficient to pacify the offended deity. The Philistine account is distinctive in its references to sending a “guilt offering” (v. 3) and to giving “glory to Israel’s god” (v. 5).

6:4 Five gold tumors and five gold rats. It seems likely, especially given their stated intent to “give glory to Israel’s god” (v. 5), that the use of gold is a sign of honor and submission. Further, the golden objects (tumors/mice) probably served an apotropaic function (see previous note). Like the Israelite scapegoat of Lev 16 that was to “carry on itself all their sins to a remote place” (Lev 16:22; see note on Lev 16:10), the golden tumors/mice were meant to bear away the plague afflicting the Philistines. A similar procedure involving a mouse is attested in the Hittite Ambazzi ritual, wherein the practitioner declares: “I have taken away from you evil and I have put it on the mouse. Let this mouse take it to the high mountains, the deep valleys and the distant ways!” (Ambazzi ii 37–40).

6:7–9 In keeping with the ritual character of the proceedings, the Philistines prepared a new cart (thus ritually clean), to which they attached cows that had recently calved. The point of the exercise, as explicitly stated in v. 9, was to determine whether their distress was wrought by the Israelites’ God or whether it had come upon them for some other unknown reason. As v. 7 explains, the cows chosen to pull the cart had never been yoked before and had recently given birth to calves. If, contrary to nature, they should forsake their calves and, accepting the yoke, pull the cart toward Israelite territory, this abnormal behavior would be a sure sign that Israel’s God, Yahweh, was the cause of their recent distress. For partial analogues to the ritual procedure, see note on v. 2. The aims of the Philistine procedure were to ascertain the cause of their affliction, to pacify the offended deity if necessary, and to bear the plague away by sympathetic magic.

6:19 struck down . . . because they looked into the ark. The text gives no indication of the mode of death inflicted here. The number given of those who died (70) may simply be a convention indicating a large number (some manuscripts indicate 50,070; see the article “Numbers in Numbers”). Nu 4:4, 15, 20 forbids even priests from looking at the ark, but this passage indicates that the victims engaged in more than incidental glances. Treating a holy object as a common curiosity violates the sanctity of the ark and would have been recognized as an act of desecration.

7:6 they drew water and poured it out before the LORD. Although this apparently ritual act of pouring out water before the Lord (called a “libation”) is without specific parallel elsewhere in the OT, its association with fasting and confession in the present context suggests that at least in this instance it is meant to imply repentance and a desire to do serious business with God. Water (as well as beer and wine) libations are attested throughout the ancient Near East. Water libations in Mesopotamia and in Syria-Canaan appear to have been offered as drink for the gods, just as animal sacrifices represented food for the gods. For ancient Israel, however, such practices appear to have been emptied of their literal significance even while being retained as ritual features with symbolic significance. fasted. Fasting is not commonly found in the ancient Near East, except in the context of mourning (see note on 2Sa 12:16). In the OT, it can be seen as part of a purification process, usually in connection with making a request before God. leader. The Hebrew word here is the same word elsewhere rendered “judge” (e.g., Jdg 2:16; 3:10). Samuel is depicted as combining several roles, namely, prophet, priest and judge. The transitional period in which Samuel served, along with the dint of his own personality and divine calling, may well account for his combining of roles that would, at a later period in Israel’s development, have been kept quite separate.

7:7 the Philistines heard that Israel had assembled. That word of an Israelite assembly in progress should raise concern among the Philistines is understandable, given the fact that in the ancient Near East impending battles were typically preceded by religious assemblies designed to entreat the deity for a favorable oracle. Babylonian and Assyrian historical texts ranging in time from Hammurapi (eighteenth century BC) to the siege of Jerusalem by Sennacherib a thousand years later make frequent reference to trust-inspiring oracles from the deity/deities prior to battle. Mediation of the oracle through prophets or priests is not explicitly mentioned in these passages, though the king sometimes assumes the title of high priest. An inscription from the reign of Ashurnasirpal II (884–858 BC), however, distinguishes “king” and “diviner” among the conquered forces of Karduniash, and it is particularly noteworthy that the diviner is also described as a “commanding officer,” suggesting a combined religious and military role. In the OT it was customary to “consecrate” war and to speak of warriors as “consecrated.” An attempt to consult Yahweh, through priest or prophet or otherwise, generally preceded battle and was sometimes accompanied by sacrifice and/or prayer (see the article “Divine Warfare”). In the light of all this, it is perfectly understandable that the Philistines would have been concerned that the assembly of Israelites at Mizpah at a time unconnected to a regular festival might signal a precursor to war.

7:8–9 “Do not stop crying out to the LORD our God for us . . .” Then Samuel took a suckling lamb and sacrificed it as a whole burnt offering. Samuel’s sacrifice accompanied his crying out to Yahweh in a time of military distress. This combination of prayer and sacrifice in a context of military crisis is found also in a Ugaritic prayer-song to the god El.

7:10 the LORD thundered . . . against the Philistines. See note on 2:10.

7:12 took a stone and set it up . . . named it Ebenezer. The use of (often inscribed) boundary stones was widespread throughout the ancient Near East. The stones were sometimes named and were believed to be under divine protection. Curses against those who might move them were sometimes included in the inscription.

7:14 Amorites. In the books of Samuel, the Amorites are mentioned only here and in 2Sa 21:2 (the Gibeonites being survivors from a former Amorite population). Along with the Canaanites, the Amorites are frequently mentioned as among the early inhabitants of the land of promise prior to the arrival of Israel. See note on Jdg 1:34.

7:17 he built an altar there to the LORD. With Shiloh having suffered destruction at the hands of the Philistines in the aftermath of the Israelite loss in ch. 4, sacrifices could no longer be offered there (on Shiloh, see note on 1:3). Whether Samuel’s altar at Ramah was intended for sacrifice or merely as a memorial is not specified by the text, but the former seems more likely. While the proliferation of local altars was discouraged after the establishment of Jerusalem as Israel’s central sanctuary, there was no absolute prohibition at earlier periods, only a command not to sacrifice in the Canaanite way (Dt 12).

8:3 accepted bribes and perverted justice. It is not only in the Bible that accepting bribes and perverting justice is considered a serious offense. In a well-attested Hittite text containing instructions from “His Majesty Arnuwanda the great king” to his officials in border towns, the king insists that “border governors” (perhaps analogous to the role held by Samuel’s sons) are to judge each case appropriately and make things right or else refer it to the king himself. The recipient is specifically warned against perverting justice by taking a bribe and consequently swinging a case in the favor of one party or another. Samuel’s sons are therefore guilty of actions that would be considered criminal in other nations as well as Israel.

8:7 they have rejected me as their king. Not just in Israel, but in the ancient Near East generally, kingship was intertwined with religion. While in Egypt the king himself was worshiped as divine, in Mesopotamia kingship was regarded as one of the basic institutions of human life devised by the gods for mankind. The concept of divine sponsorship of kingship was foundational in the cognitive environment of the ancient Near East. In Israel, the emphasis fell on God himself as the Great King, with the human king to serve not as a demigod, but as vice-regent (vassal) to the Great King. The “law of the king” in Dt 17:14–20 makes it clear that the king in Israel was to be subservient to the divine law and was “not [to] consider himself better than his fellow Israelites” (Dt 17:20). The people have not concluded that they don’t want God leading them anymore: No one in the ancient Near East would want that, and that is not a king like the nations have. Rather they want a king who would successfully bring the deity into play so that they could carry out their national agendas instead of waiting on the action of the deity alone (as when he appointed judges over them). They wanted God’s power, but not his control.

8:11–17 Whatever advantages the elders imagined a king like those of the nations would bring, Samuel—speaking for Yahweh—was intent on making plain the disadvantages that kingship, particularly if self-serving in character, would bring. Perhaps Samuel’s warning progresses from the less obviously abusive royal practices (v. 11) to the more obviously abusive ones (v. 17). In any case, it is understandable that a centralized monarchical government would require courtiers and servants of the court, agricultural workers for the king’s fields, artisans to craft the king’s weapons (v. 12), domestic workers to prepare meals for the court and to keep the palace (v. 13), and a standing army to protect it all (vv. 11–12). To make all this happen, there would be royal taxation and expropriation of “the best” of the fields, flocks and servants of the people (vv. 14–17). The end result, Samuel warned, would be that “you yourselves will become his slaves” (v. 17). These were the realities of kingship at the end of the second millennium BC.

8:11 He will take your sons. Sons were particularly important in the ancient Near East—for reasons relating to the security and continuity of the family line—but, as Samuel warned, the king “will take your sons” to serve the king. make them serve with his chariots and horses, and they will run in front of his chariots. The practice Samuel describes finds a loose analogy in a Hittite text prescribing the protocol to be followed by the royal guard whenever the king travels. Samuel’s warning that they would be required to run in front of the king’s chariot may not have sounded particularly negative to Israel’s elders. Indeed, a couple of eighth-century BC Aramaic inscriptions seem to suggest that “running at the wheel” of one’s lord was an honor, though the fact remains that the absence of sons would prove a hardship, e.g., at harvest time.

9:1 a Benjamite, a man of standing . . . Kish. As a small tribe wedged between the much more powerful tribes of Judah to the south and Ephraim to the north, and as the home of the yet to be conquered city of Jerusalem, Benjamin, which had nearly been annihilated in the judges period, was an ideal choice as home of Israel’s first centralized regime, as it would have been less likely to provoke jealousy among the other tribes.

9:2 Saul, as handsome a young man as could be found. In the ancient Near East, a high priority was placed on the commanding appearance and heroic qualities of leaders (e.g., Gilgamesh). By ancient Near Eastern standards, therefore, Saul showed great potential.

9:7 what can we give the man? In the ancient Near East, prophets, prophetesses, diviners and the like were sought out for consultation on all manner of issues ranging from health and fertility to religious observance, political fortune, military enterprises, lost items, and more. Recipients of services naturally expected to pay and generally did so without need of reminder. Remuneration for solicited prophetic services is well attested in the Mari corpus, where payment is occasionally even explicitly demanded. Unsolicited prophetic revelations, which would describe most Biblical prophecies, were often delivered without expectation of payment. In fact, the Biblical writing prophets express disapproval of those who prophesy for money: Amos denies being such a prophet (Am 7:12–15), and Micah explicitly condemns prophets who divine for money (Mic 3:5, 11; cf. Jer 6:13). The attitude of preliterary Yahwistic prophecy is less clear, however, making it difficult to decide whether Saul’s concern to pay the “man of God” was normal or, as Josephus suggests (Antiquities 6.48), yet another hint of religious ignorance.

9:8 quarter of a shekel of silver. Silver was a common form of currency in Canaan, as well as in Assyria and Babylonia. In Hebrew, the word for “silver” eventually came to mean “money” as well. A quarter shekel would have weighed about one-tenth ounce (three grams) and would likely have represented several days’ wage for any ordinary worker. It seems likely, then, that the quarter shekel available to Saul would have been a more or less appropriate payment for a solicited inquiry.

9:9 prophet . . . seer. Prophets and seers perform similar functions, but their roles in society are structured differently (not dissimilar from the difference between a “king” and a “judge.”) The emphasis in this passage is on terminology, however, not sociology. “Seer” emphasizes the source of the message (received in visions); “prophet” emphasizes the proclamation of the message to its target audience. See the article “Prophets and Prophecy.”

9:11 they met some young women coming out to draw water. At least until underground water systems were developed (e.g., see notes on 2Sa 2:13; 5:8), village dwellers had to make periodic trips to draw water from the nearest source, often near the base of the hills on which most towns were situated. Wells or springs, located on the outskirts of towns, were often the places where newcomers to town first met townspeople, often women, who typically bore the responsibility of porting water.

9:12 high place. “High places” (Hebrew bamot; singular, bamah) are mentioned over a hundred times in the OT. The word is used in the OT in a mundane sense to mean “hill,” “height,” “ridge,” and in a religious sense to mean a sacred “high place,” either a worship site on a natural elevation or a raised platform. Often sites of Canaanite worship, “high places” are viewed in the OT as endangering the purity of Israelite worship (see, e.g., Nu 33:52; Dt 12:2–3; Jer 2:20). Nevertheless, in the period between the destruction of the sanctuary at Shiloh and the building of the temple in Jerusalem, worship of Yahweh at “high places” was sometimes conducted without explicit censure, as in the present passage. After the division of the kingdom, worship at “high places” constituted a severe problem both in the north (1Ki 12:31–32; 13:32–34) and in the south (1Ki 14:22–24). Removal of the “high places” became a major goal of reform movements under southern kings such as Hezekiah (e.g., 2Ki 18:4) and Josiah (e.g., 2Ki 23:5). With Shiloh destroyed and the ark in exile, this might be serving as the central sanctuary.

9:15 the LORD had revealed this. On the various modes of divine revelation, see notes on 28:3, 7; see also the article “Consulting a ‘Spirit.’ ”

9:24 Eat, because it was set aside for you for this occasion. Having instructed the cook to set aside a special cut of meat (v. 23), namely, the shank (NIV “thigh”), Samuel has it placed before Saul. Special portions of meat were often reserved for important personages, as in the case of an officiating priest, who was to receive the right shank of the sacrificial animal (Lev 7:32–34). That a special portion had been set aside for Saul in advance of his arrival suggests both the momentousness of the occasion and its providential direction.

10:1 flask. Connotes a small jug or vial. Special oils and cosmetics, because of their preciousness, were often held in tiny containers in antiquity, as today. poured [oil] on Saul’s head. Anointing is known from Hittite enthronement texts; Egyptian and Mesopotamian kings were not anointed, though the pharaohs anointed their vassals and officials. It is possible that anointing represents a contract between the ruler and the people, hence the anointing of David by the people in 2Sa 2:4. Texts from Nuzi show individuals anointing each other when entering a business agreement, and anointing with oil occurred in Egyptian wedding ceremonies. ruler. In this context means something like “king-elect” or “one who is designated as leader of the people.” inheritance. The Lord’s “inheritance” comprised both the land and the people of Israel (Dt 32:9). In acceding to the people’s demand for a king, Yahweh did not relinquish his rights as Great King over his inheritance to the human monarch. Rather, the human king was to be Yahweh’s vice-regent and was to subordinate himself within an authority structure that Yahweh himself would stipulate (v. 25). Prior to the monarchy, judges had been raised up by Yahweh on an ad hoc basis and had both received and carried out Yahweh’s instructions. With the inauguration of kingship, however, the tasks of receiving and carrying out Yahweh’s instructions were initially divided between prophet (Samuel) and king (Saul). The former would be Yahweh’s mouthpiece to the king, and the king was to carry out Yahweh’s instructions as received through the prophet. This authority structure is evidenced in the first charge Saul receives in vv. 7–8, and grasping its significance is essential to understanding the nature of the eventual breach between Saul and Samuel/Yahweh.

10:5 a procession of prophets . . . prophesying. Though prophets and prophecy were not unknown in Israel’s premonarchical period—e.g., Abraham, Moses, Miriam and many others were described as prophets—it was with the inception of monarchy that the prophetic office and the prophetic guild came into their own. Prophecy was a skill in which one could train, and groups of these trainees, described as “sons of the prophets,” began to appear, often under the leadership of a prominent individual. 1Sa 19:20 will find Samuel himself presiding over such a group of prophets. It was one such band that Saul encounters at Gibeah, and they are playing musical instruments and prophesying (a word that implies a trancelike state). The use of instruments was intended to induce a trancelike state (“ecstasy”) in which one might become receptive to prophetic oracles. The Mari tablets describe an entire class of ecstatic prophets who served as temple personnel.

10:6 The Spirit of the LORD will come powerfully upon you, and you will prophesy with them; and you will be changed into a different person. Bestowal of the divine Spirit often connoted God’s empowering of an individual for the accomplishment of a particular task, usually involving calling out the tribes to war, something only Yahweh has the authority to do. Conversely, the Spirit of God might thwart someone intent on a particular action (e.g., 19:23). Verse 10 of the present episode describes the “Spirit of God” coming “powerfully” upon Saul, a verbatim repetition of what was often said of Samson in the book of Judges (Jdg 14:6, 19; 15:14). Such visitations of the Spirit appear to have been temporary and designed to empower (or prevent) a particular action. In Akkadian texts the presence of a deity with a king was indicated by the king receiving the melammu—a glow that regularly accompanied deity.

10:9 God changed Saul’s heart, and all these signs were fulfilled. See note on v. 6.

10:10 the Spirit of God came powerfully upon him. See note on v. 6.

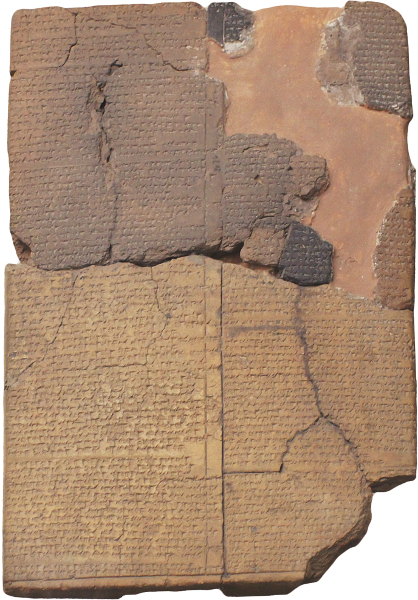

10:25 Samuel explained to the people the rights and duties of kingship. He wrote them down on a scroll and deposited it before the LORD. The notice of this verse raises three interesting questions: What were these “rights and duties of kingship”? What was the state of writing and literacy in Samuel’s day? And what did it mean to deposit something before the Lord? None of these questions can be answered with certainty, but studied conjectures can be offered. The “rights and duties of kingship” would likely have stipulated the responsibilities of the people to the king, the king to the people, and, most significantly, the king to Yahweh (perhaps along lines similar to the law of the king in Dt 17:14–20). Assyrian kings would sometimes make formal agreements (adu-agreements) with their servants “in front of the great gods.” Something similar may be implied in the verse here, but the text offers little detail.

The question of popular literacy in ancient Israel is widely debated, but Samuel’s upbringing as a priest in the house of Eli would likely have afforded educational opportunities beyond the ordinary. Evidence suggests that a basic level of literacy was common, but most people would rarely have occasion to read or write. A formal document like the one mentioned here would be executed by someone with scribal training.

The statement that the document was deposited “before the LORD” suggests that it was deposited in the sanctuary. In the ancient Near East as well—e.g., among the Hittites—covenant documents were frequently deposited in sanctuaries. Other Biblical references to documents deposited before the Lord include Dt 31:26; Jos 24:26. The rationale is not given, but presumably this was intended to keep the information visible to the deity.

10:27 some scoundrels said, “How can this fellow save us?” While culpable for refusing to accept the one whom Yahweh had chosen, the “scoundrels” (“insurrectionists”) nevertheless asked a valid question, especially when viewed against the typical process by which leaders in the ancient Near East often came to power. As several studies have shown, the accession process in the ancient Near East typically comprised three stages: (1) divine designation of the new leader, (2) some kind of demonstration by the new leader that would gain public attention and rally support, (3) public confirmation of the new leader. If all had gone according to plan, Saul’s anointing and first charge (vv. 1–8) would have served as his designation (stage 1); an attack on the Philistine outpost in Gibeah of God would have served as the demonstration (stage 2); and a public confirmation of Saul as Israel’s first king would have followed (stage 3). Saul’s failure to execute stage 2 meant that he did not come to public attention. To rectify this situation, Samuel convened the assembly at Mizpah, where Saul was selected by lot (vv. 17–24). This meant, however, that Saul had still done nothing to distinguish himself or gain public confidence; in fact, he had been dragged from hiding among the supplies (vv. 22–23). Eventually (ch. 11), Saul’s victory over the Ammonites would silence the dissenters, but it would leave his first charge—intended to test his fitness as a vassal-king to Yahweh—yet unfulfilled. Only in ch. 13 would the first charge come back into play, and there Saul would fail.

11:1 Nahash. See note on Jdg 11:12. Ammonite. See notes on Ge 19:37–38; Dt 2:19.

11:2 gouge out the right eye. In the ancient Near East, losing a battle sometimes resulted in physical mutilation of one sort or another, and punitive action by regimes against those considered rebels often included mutilation such as the removal of eyes, ears or hands. In the present context, submission to mutilation is presented as a precondition for avoiding battle. Such a precondition is so far unattested in other ancient Near Eastern literature. The purposes of blinding the vanquished varied, as the Bible itself indicates: Samson was blinded by the Philistines to humiliate and incapacitate him (Jdg 16:21); King Zedekiah of Judah was blinded by the king of Babylon in order that his last visual memory might be the slaughter of his own sons (2Ki 25:7; cf. Jer 39:6–7). In the case before us, the Ammonite king’s intention was certainly to humiliate the Jabesh Gileadites, but also, it seems likely, to render the fighting men ineffectual in battle. As Josephus (who was a successful general before he became a historian) explains, “Since the left eye was covered by the buckler” (i.e., the shield), blinding the right would render the warriors “utterly unserviceable” (Antiquities 6.68–72). Right-handed warriors (the majority) would be able to see very little in battle, unless they were willing to lower their shields or literally stick their necks out. In any case, with only one eye, they would lack depth perception and thus be at a severe disadvantage in hand-to-hand combat. Sparing the left eye would leave them capable of agricultural work and menial tasks, but little else.

11:4 When the messengers came to Gibeah of Saul. The Hebrew text of this verse could as well be rendered, “So the messengers came to Gibeah of Saul.” It seems likely that the messengers were in fact sent directly to Gibeah and not “throughout Israel” (the elders’ request in v. 3 involving an element of deception). Not only would this have been a logical action after the assembly in Mizpah in which Saul was selected as Israel’s king-elect, but pragmatic considerations make a more general dispersal of messengers unlikely. The rate of march for armies in the ancient Near East was about 15–20 miles (25–30 kilometers) a day. Messengers on an urgent mission could probably double that rate. The distance from Jabesh Gilead to Gibeah would have been 50–60 miles (80–100 kilometers), depending on the route taken. This would place the messengers in Gibeah late on the second day. Their subsequent dispersal “throughout Israel” (v. 7) would have taken another two or three days, leaving two or three days of the permitted seven days for the general muster at Bezek (vv. 7–8).

11:7 He took a pair of oxen, cut them into pieces, and sent the pieces by messengers throughout Israel. The intent is to evoke a strong reaction, reinforced by the threat that those who do not respond may suffer similar treatment. The ancient Near East was accustomed to gruesome actions intended to prompt a certain response. A tablet from Mari (ARM 2.48), e.g., records a request for permission to sever the head of a prisoner and parade it throughout the territory so as to shock reticent warriors into assembling for battle.

12:3 Testify against me in the presence of the LORD and his anointed. It was widely understood in the ancient Near East that those in positions of power were responsible to execute justice and to protect the vulnerable in society (see notes on 8:3; 2Sa 7:1; 15:4; 21:17; cf. 2Sa 5:12; 12:1–4). When rulers were deposed, it was not uncommon for those who replaced them to trump up charges of injustice against them and seek to eliminate them. Thus, Samuel was intent on clearing his name, before redefining his leadership role. While the context is markedly different, the “negative penance” section of the Egyptian “Book of the Dead” employs phrases in some respects similar to Samuel’s protestations: e.g., “I have committed no injustice against men. I have not mistreated the cattle (of God) . . . I have not done violence to a poor man . . . I have neither increased nor diminished the bushel.” Similar protests are attested in the archival records of Hittite court cases.

12:17 Is it not wheat harvest now? Wheat harvest took place early in Israel’s dry season (in May–June). In this period of almost complete drought, Yahweh’s sending of “thunder and rain” at Samuel’s request would serve both as a sign of divine approval for Samuel and as a mild punishment for Israel’s sin, as rain is never welcome at harvest time. Specifically, rain at harvest time can cause what is called preharvest sprouting: Water is absorbed into the head of the grain, stimulating hormone production leading to germination. The end effect is a lower-quality yield.

13:1 Saul was thirty years old when he became king, and he reigned over Israel forty-two years. As the NIV text notes indicate, the numerals “thirty” and “forty” do not actually appear in the Hebrew text, which reads literally, “Saul was a year old when he became king, and he reigned over Israel two years.” This appears to be a (defective?) regnal formula. In the historiography of the OT, regnal formulae stating the age of the king at accession and the length of his reign typically mark the official beginning of a king’s reign (cf., e.g., 2Sa 2:10; 5:4; 1Ki 14:21). Clearly, Saul could not have been literally a year old when he began to reign. Perhaps the number is to be understood differently—e.g., perhaps it had been a year since Saul’s anointing, and perhaps the two-year reign referred to the time elapsed between Saul’s inauguration and his definitive rejection by God in 1Sa 15:23, 28. If the regnal formula is to be read literally, however, then we must assume that one or two numerals are missing from the text. Examples of omitted numerals do occur in the ancient Near East: e.g., in two economic texts from Ur, in a list of personal names from the Old Babylonian period, in the Sumerian King List, in the Babylonian Chronicles, and more. At present the question of Saul’s age at accession must remain open, but a rough estimate would make him at least 40, assuming that the events of ch. 13, in which Saul’s son Jonathan is already in charge of troops, took place early in his reign.

In one place, Josephus accords Saul a reign of 20 years (Antiquities 10.143). In another place, the text of Josephus states that Saul reigned 18 years during Samuel’s lifetime and “two and twenty” thereafter. But the “twenty” is text-critically and logically dubious; if Saul reigned 22 years after Samuel’s death, and David became king at age 30, upon Saul’s death, then at the time of Samuel’s death David would have been only 8 years old, having already killed Goliath, served as a commander in Saul’s army, incurred Saul’s jealousy, escaped to the Philistines, gathered a troop of 600 men while on the run in the wilderness and so on. Full discussion is not possible here, but a reign of about 20 or 22 years for Saul seems to work best.

13:2 three thousand. This is probably a number of retainers, not the actual size of the mustered army, which would have been larger. Three “thousand” might also refer to three “units” or companies (see the article “Numbers in Numbers”). Standing armies usually consisted of trained soldiers and/or mercenaries, and would be deployed in border posts, garrisons or the royal guard.

13:3 trumpet. Hebrew shofar, which designates a “sounding horn” crafted (usually) from the horn of a ram (see note on Jos 6:4).

13:5 three thousand chariots. It is possible that this number represents the accepted and familiar practice of hyperbole in military reports. If not, see note on Jdg 4:3. Further information to consider is that the Hebrew text refers to 30,000 chariots, while the Septuagint (the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT) and Syriac attest the number 3,000. Even the lower figure seems high by ancient Near Eastern standards, though not impossible: e.g., Sisera had 900 (Jdg 4:3); David killed 700 Aramean charioteers (2Sa 10:18); Solomon had 1,400 chariots (1Ki 10:26); Tukulti-Ninurta II had “2,702 horses in teams [and chariots], more than ever before.” If the NIV is correct in reading also “six thousand charioteers,” then this would further confirm that the Philistines had 3,000 (and not 30,000) chariots. The word translated “charioteer” can also be rendered “horseman/cavalryman” and “(chariot) horse.” In view of the fairly late introduction of cavalry in Canaan and the pictorial evidence of traveling bands of Philistines comprising three main elements: chariots, infantry, and noncombatants, but no cavalry, the decision of many modern translations to read “cavalry” or “horsemen” seems misguided. Moreover, if the Philistines, like the Hittites, employed three-man chariot crews, then the number 6,000 would best refer to the chariot horses, not the charioteers (which would have numbered about 9,000). That said, some variation of the chariot team is certainly possible. Assyrian chariot crews could consist of two, three or even four men. There is also possible evidence of two-man chariots among the Mycenaeans, to whom the Philistines are thought to be related.

13:14 after his own heart. Probably means “of his own choosing.” The phrase does not necessarily reflect the piety of David, but demonstrates God’s exercise of will in the rejection of Saul. In the Babylonian “Chronicle Concerning the Early Years of Nebuchadnezzar II,” Nebuchadnezzar captures Judah and puts a king of his own choice (“according to his own heart”) on the throne. This descriptive phrase is also used commonly in royal inscriptions dating more than a thousand years earlier to indicate that the king met the god’s criteria. Saul, in contrast, had met only the people’s criteria.

13:19 Not a blacksmith could be found in the whole land of Israel. Whether the Philistines led their neighbors in ironworking technology or simply were militarily powerful enough in this period to deny Israel access to blacksmiths remains an open question. Iron objects are not unknown prior to the so-called Iron Age, but at earlier periods iron was generally not preferred to bronze (an alloy of copper and tin), because bronze was in fact stronger than simple wrought iron. Only when iron was “carburized” (had carbon added to it) and “quenched” (doused in cold water) did it become steel. Because of its higher melting temperature (1528°C [2782°F], as opposed to 1200°C [2192°F] for copper), iron could not be melted and cast; ancient furnaces could achieve at best 1300–1400°C (2372–2552°F). The only solution was “forging”—repeatedly heating and then hammering the spongy hot iron to remove slag and compact the metallic iron. In most parts of the ancient Near East, iron ore was in fact more common and available than copper or tin, but the technological challenges of smelting iron meant that its use for weapons and tools did not become widespread until shortages of (often imported) copper and tin created a necessity that could not be ignored. There are even earlier references to metallic iron (cf. Og’s bed decorated with iron [Dt 3:11]), which treat it as a luxury item, obtained most often from meteors (the Egyptian word for iron means “metal of heaven”). The point, in any case, is that the Philistines prevented the Israelites from arming themselves properly. Since bronze weapons (i.e., weapons produced without iron technology) would still have been useful to the Israelites, this verse probably means the Philistines prohibited metalworking of any sort.

13:21 two-thirds of a shekel . . . a third of a shekel. If the average monthly wage was one shekel, then these charges were exorbitant.

14:1 armor-bearer. He not only is a porter of equipment, but also serves a function similar to a squire or apprentice while fighting alongside the king.

14:2 Saul was staying on the outskirts of Gibeah under a pomegranate tree in Migron. The word “tree” is not present in the Hebrew text; “pomegranate” may refer to a certain large cave in the south wall of the wadi. The cave’s pitted interior gives it the resemblance of an open pomegranate and may have earned it the name “Rimmon” (Hebrew for “pomegranate”). Jdg 20:45 speaks of “the rock of Rimmon” to which 600 Benjamites fled, and so it is conceivable that the 600 men with Saul could have been stationed “under the Pomegranate.” Saul’s location in a cave would also explain his need for lookouts to inform him of activities in the Philistine camp (v. 16).

14:3 ephod. See note on 2:18. In the present context, the ephod that Ahijah is “wearing” (or “carrying”—the Hebrew verb can mean either) was probably the high priestly ephod containing the Urim and Thummim, devices used in divine inquiry (see notes on vv. 18–19; Ex 28:15; see also the article “Urim and Thummim”). The presence of these oracular instruments among Saul’s entourage might encourage hope that Saul would seek and receive divine guidance, as David did on several occasions, using the ephod (1Sa 23:9–12; 30:7–8). Ichabod’s brother Ahitub son of Phinehas, the son of Eli. The bearer of the ephod, Ahijah, is provided with a genealogy that not only identifies him as a member of the rejected priestly house of Eli, but makes a rather unusual step sideways to mention an uncle, Ichabod, whose name means something like “no glory” (see NIV text note on 4:21). Commentators have struggled to explain this genealogy, but its purpose is probably to recall, if only indirectly, that Saul’s glory too is much diminished after the events of ch. 13.

14:6 uncircumcised men. See note on Jdg 14:3. Nothing can hinder the LORD from saving, whether by many or by few. Though distinctive in its monotheism, Israel’s belief that the Divine Warrior ultimately decided the outcome of battles was not without analogy among neighboring peoples. The ancient Near Eastern pantheons included gods or goddesses of war—Baal and Anat in Canaan, Nergal and Ishtar in Assyria, Marduk in Babylon and so forth. Battles were regarded as ultimately decided by the gods, the stronger god defeating the weaker. Thus, an inferior human force led by a superior deity could defeat a superior human force led by a lesser deity. In the present instance, Jonathan’s faith in the power of Yahweh emboldens him to go over, accompanied only by his armor-bearer, to confront an entire Philistine troop.

14:15 the ground shook. It was a panic sent by God. In keeping with their belief that in warfare the gods actually did battle (see notes on v. 6; Jdg 1:2; 3:10; see also the article “Combat by Champions”), peoples of the ancient Near East associated this divine activity with dramatic manifestations in nature, the shaking of the earth, the splitting of the heavens, thunder and storm and so forth (cf. 2Sa 22:8–10). In the present passage, Yahweh manifests himself by causing the ground to shake and by throwing the Philistines into confusion so that their swords are turned upon each other (v. 20).

14:18–19 Bring the ark . . . Withdraw your hand. Having learned that Jonathan and his armor-bearer had left the camp, Saul orders Ahijah to “bring the ark of God.” Mention of the “ark” is surprising at this point in the narrative for the following reasons: (1) in v. 3 Ahijah is in possession of an “ephod,” not the ark; (2) judging from 7:1 and 2Sa 6, the ark appears to have remained at the town of Kiriath Jearim throughout the reign of Saul (1Ch 13:3 confirms that the ark was not sought during Saul’s reign); (3) Saul’s order that Ahijah “bring” the object seems appropriate in reference to an ephod (cf. 23:9; 30:7) but not in reference to the ark; (4) Saul’s command in v. 19 to “withdraw your hand” makes little sense if the ark is in view, but excellent sense if Ahijah is in the process of grasping the Urim and Thummim, or the container holding them, in the breastpiece of the priestly ephod. Based on Akkadian evidence, it is possible that oracular inquiry using the Urim and Thummim was a form of psephomancy, “divination by means of white and black stones” (see the article “Urim and Thummim”). Considerations such as these have led a majority of commentators to follow the Septuagint (the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT) (cf. also Josephus, Antiquities 6.115) in reading “ephod” instead of “ark” in the present context—the two words are orthographically fairly similar in Hebrew. It seems likely, then, that Saul initiated an oracular inquiry involving the ephod but almost immediately aborted the process when it became apparent that the battle was heating up. Having failed to wait for Samuel in ch. 13, Saul now finds it difficult even to wait the few minutes necessary to inquire of Yahweh regarding the battle in progress, and this trend of increasing indifference to gaining divine direction adds to the unfavorable portrayal of Saul. On the customary practice in the Bible and the ancient Near East of seeking divine guidance before entering battle, see note on 7:7.

14:21 Hebrews who had previously been with the Philistines . . . went over to the Israelites. This statement seems to distinguish “Hebrews” from Israelites. The “Hebrews” here may refer to the Habiru/Apiru, landless, troublesome mercenaries who may have shifted allegiances opportunistically (see note on 4:6).

14:24 Cursed be anyone who eats food. In the ancient Near East, fasting is often associated with mourning, but is unattested in battle contexts such as this.

14:33 sinning against the LORD by eating meat that has blood in it. Not just in the OT but throughout Egypt, Mesopotamia and the Levant, blood was regarded with awe as the medium that carried and contained life. As such, it gave rise to seemingly conflicting attitudes. Contact with it was regulated by taboos, yet ways to use its power were developed in ritual. In the OT, control over the lifeblood was understood to belong to God, the giver of life, and prohibitions against eating blood were pervasive (e.g., Ge 9:4; Lev 3:17; 7:26–27; 17:10, 12; 19:26; Dt 15:23; Eze 33:25).

14:35 Saul built an altar. When an animal was laid on an altar, in the process of sacrifice the blood drained out as regulations required. By building an altar, Saul is facilitating proper sacrifice. Consequently we can see that though he has some ritual knowledge and sensitivities, he still lacks an overall sense of doing what is necessary to please God (obedience).

14:37 God did not answer him that day. Though Urim and Thummim represent some sort of system like lots (see the article “Urim and Thummim”), and therefore tend to address binary questions (yes/no), it is likely that the same answer had to be drawn several times in a row to confirm that the answer came from God. If this is so, it would explain how an answer could fail to result from the inquiry process.

15:2 Amalekites. See note on Nu 13:29. Ex 17:14 singles out the Amalekites as enemies of Israel. The severity of the treatment of the Amalekites commanded by Yahweh here in vv. 2–3 must be seen in the light of this status and ongoing opposition to Israel (see, e.g., Jdg 3:13; 6:3–5, 33; 7:12; 10:12).

15:3 totally destroy. See note on Dt 2:34.

15:4 two hundred thousand foot soldiers. See the article “Numbers in Numbers.”

15:6 Kenites. See note on Jdg 1:16. Not only in the present context of Saul’s battle against the Amalekites but elsewhere in the Bible (e.g., Nu 24:20–21) Kenites and Amalekites are mentioned together. But whereas the Amalekites were consistently hostile toward Israel, the Kenites were consistently friendly, and so Saul was careful to send the Kenites away from danger before attacking the Amalekites.

15:12 Carmel. See note on 25:2; cf. 23:24. he has set up a monument in his own honor. It was common practice in the ancient Near East for victorious kings to set up monuments, or victory steles, with inscriptions celebrating their glorious achievements and crediting their success to their god(s). The ninth-century BC Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II, e.g., makes repeated reference to erecting steles or statues in praise of his mighty power. In the aftermath of one victory, apparently not content with a single monument to himself, he erected a “colossal royal statue of [him]self” in the palace of his vanquished foe and also deposited steles in praise of his own might in the enemy’s gate. Saul’s monument may have been such a victory stele. Absalom will later honor himself similarly with a monument (2Sa 18:18).

15:23 rebellion. The same Hebrew word used of Israel’s contentiousness in the wilderness; it refers to “pressing one’s case.” divination. Acquiring information about the desires of deity by indirect means. Here, Saul’s “case” is that he (thinks he) knows what will please Yahweh (sacrifices from the plunder), so his assertion of that knowledge in his own defense (his “case” or “rebellion”) is like divination. idolatry. The word in the original Hebrew text is “teraphim,” see the article “Household Gods.”

15:27 Saul caught hold of the hem of his robe, and it tore. The precise significance, or intent, of Saul’s seizing the hem of Samuel’s robe is uncertain. In addition to several texts in Akkadian, at least one reference to this action can be found in Old Aramaic, as well as one other in the OT, namely, Zec 8:23: “This is what the LORD Almighty says: ‘In those days ten people from all languages and nations will take firm hold of one Jew by the hem of his robe and say, “Let us go with you, because we have heard that God is with you.” ’ ” In the light of these texts, Saul’s grasping of Samuel’s hem might be read positively, as indicating supplication or submission. However, this positive construal of Saul’s action assumes more regarding Saul’s motives than the context will support. A further instance of grasping the hem is found in the Ugaritic myth of Baal and Mot, in which Anat seizes the hem of Mot’s garment in order to constrain him. Anat’s action, in context, is suggestive of supplication but hardly of penitence or submission; when she next “seizes” Mot, Anat “hacks him up, pulverizes him, and scatters his remains for the birds to eat.” Taking this evidence together, we may conclude that grasping the hem can mean various things in various contexts. In the present context, Saul’s grasping and (inadvertently?) tearing the hem of Samuel’s robe is best understood as a last desperate attempt to rescue a situation that has gone badly wrong and to wrest from the prophet a word of comfort or concession. As it happened, however, the torn robe became simply a symbol of the kingdom now “torn” from Saul (v. 28).

15:29 the Glory of Israel does not lie or change his mind. The ninth-century BC Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II begins one of the longest extant Assyrian royal inscriptions with line after line of praise to the god Ninurta, whom he describes as, among other things, “the splendid god who never changes (his mind).” In the context of the trial of Saul, the sense seems to be similar: No amount of cajoling or manipulation will succeed in mitigating the sentence that has been pronounced against Saul, for it has been issued by Yahweh, whose judgment is supreme.

16:1 Fill your horn with oil. See 10:1.

16:7 the LORD looks at the heart. In the ancient Near East, the heart was viewed as far more than the seat of blind passions. Some Babylonian texts speak of the deity Shamash seeing into or searching the heart of an individual. The Hebrew concept of the heart as the center of intellectual, ethical, moral and religious consciousness was similar.

16:10–11 Jesse had seven of his sons pass before Samuel . . . “There is still the youngest.” Ascendancy of a younger brother over his elder brothers is a common motif in the Bible and in the ancient Near East generally. One particularly interesting parallel is offered by a mid-third-millennium BC Sumerian epic in which the eighth son, one Lugalbanda, joins seven older brothers and performs heroically in their attempt to conquer a city.

16:14 the Spirit of the LORD had departed from Saul, and an evil spirit from the LORD tormented him. See note on Jdg 9:23. In the ancient Near East, unworthy kings could provoke similar displeasure and disciplinary actions from their deities. For instance, near the end of the Code of Hammurapi a curse is invoked upon anyone who should disobey the law such that divine favor would be withdrawn from the offender, as it was withdrawn from Saul. The Akkadian notion of “a spirit or demon representing the individual’s vital force,” which could become alienated from the individual or driven away by evil, may offer some degree of conceptual parallel, as also to a lesser degree the Akkadian phrase referring to a good or evil spirit.

17:4 Goliath . . . was six cubits and a span. See NIV text note. A cubit was the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger, and a span was the distance from the tip of the thumb to the tip of the smallest finger of a hand fully spread. There was considerable variation in the precise lengths of cubits and spans in antiquity, but by any standard Goliath would have been over nine feet tall. A number of credible Greek manuscripts reduce Goliath’s height by a third to four cubits and a span, making him about six feet nine inches (205 centimeters)—still tall by ancient standards, to be sure, but not a giant (a claim that the Biblical text never makes in any case). It should be noted, however, that examples of giantism on the order of what the Hebrew text claims for Goliath are attested in numerous sources both ancient and modern. Within the Bible itself, both giant individuals (e.g., King Og of Bashan, Dt 3:11) and entire races of giants are described (e.g., the Anakites [see notes on Nu 13:22; Dt 2:10] and Rephaites [see note on Dt 2:11], the latter being the race of which Og was a remnant). A noteworthy extra-Biblical reference is found in the thirteenth-century BC Egyptian Papyrus Anastasi I, which “describes bedouin in Canaan, ‘some of whom are of four cubits or five cubits (from) their nose to foot and have fierce faces.’ ” Joshua, during the conquest period, was largely successful in wiping out the Anakites, but there were some survivors in the Philistine cities of Gaza, Gath and Ashdod (Jos 11:21–22). Goliath may well have been one of these survivors.

17:18 bring back some assurance from them. The English translation of this instruction from Jesse to David suggests that David was to bring back assurance that his brothers were faring well. This is one possible understanding of the Hebrew (“some pledge” or “some token,” see NIV text note). There may also be a sense that David was to bring back some indication that he had fulfilled his mission and delivered the goods. In view of the responsibility of local populations to supply troops in their area, a further possibility is that David was to bring back a token as proof that Jesse had met his obligations to supply the army.

17:22 David left his things with the keeper of supplies. If the grain and loaves brought by David (v. 17) were for the resupply of the troops, his depositing them with the “keeper of supplies” marked the fulfillment of that part of the errand. If, on the other hand, his task was to deliver the grain and loaves directly to his brothers (and the cheeses to the commanding officer, v. 18), then he was simply placing them in safekeeping so long as attention was directed toward the battle lines.

17:25 exempt his family from taxes in Israel. Taxes are not explicitly mentioned in the Hebrew text; rather, the term “exempt” is simply “free,” most often used to distinguish those who are not slaves. Attempts have been made on the basis of similar sounding terms in Akkadian and Ugaritic to liken these “free” people to particular social classes in ancient Near Eastern societies (craftsmen, farmers, serfs, etc. who fell midway between slaves and landowners), but there is no evidence of this usage or this class in Israel. Certainty of what precisely the promised freedom would have been is elusive, but it may well have involved exemption from further obligations to the king (including the obligation to pay taxes), or perhaps it even involved the right of the hero’s family to live as pensioners of the royal house.

17:26 uncircumcised Philistine. See note on Jdg 14:3. David’s words reflect a theologically based confidence similar to that of Jonathan when in ch. 14 he too went up against the Philistines despite apparently unfavorable odds.

17:37 the lion. Probably of the Asiatic variety (Panthera leo persica), which closely resembles the African lion, but is now virtually extinct—there are less than 300 still in the wild in the Gir Forest of northwestern India and 200 or so in zoos worldwide. The last sure evidence of a lion in Palestine was one killed in the thirteenth century AD. See note on Jdg 14:5. the bear. A brown bear, probably of the subspecies Ursus arctos syriacus, a somewhat smaller and paler relative of the well-known grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis). These paler-than-normal brown bears can still be found in parts of the Middle East, but they disappeared from the area around Israel in the first half of the twentieth century AD. Preferring fruits and wild forage, bears would likely have menaced livestock mostly in winter months when such vegetarian fare was scarce. Despite their seemingly gentler eating habits, bears may have been even more feared than lions because of their greater strength and more erratic behavior. Tangible evidence of lions and bears—in the form of their remains—has been unearthed by archaeologists excavating Iron Age levels in Palestine (the period of the settlement and monarchy).

17:40 sling. In Israel, slings were used mainly by shepherds to ward off marauding animals, but they were used in Egypt and Assyria as weapons of war. These slings consisted of a patch of leather or cloth, with leather straps or rope cords tied to opposite ends. Holding the ends of the cords firmly in his hand, the warrior would swing the loaded sling around above his head and then, when it had reached maximum speed, release one of the cords. The sling stones could reach speeds of 100–150 miles per hour (160–240 kilometers per hour). The stones used by the Assyrians at Lachish in the eighth century BC were two and a half to three inches (six to seven and a half centimeters) in diameter and weighed about nine ounces (250 grams). Slings were affordable but effective weapons that were used, e.g., by shepherds to drive off predators. David’s background as a shepherd would have afforded him opportunity to develop considerable skill in the use of a sling.

17:43 Am I a dog . . . ? Dogs were not highly esteemed in the ancient Near East (see note on 24:14). Goliath’s taunting words were typical in prebattle situations, especially when a contest of champions was involved (see the article “Combat by Champions,” cf. 2Sa 2:14). come at me with sticks. May suggest that Goliath did not see David’s sling, which he would certainly have known to be a dangerous weapon in skilled hands (see note on v. 40). Among the ailments that often attend giantism is poor eyesight, often a kind of tunnel vision. The shepherd’s simple sling hanging limp in his hand may have appeared to Goliath as no more than a stick, though we know from v. 40 that David had both a staff and a sling in his hands.